Raskol on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Schism of the Russian Church, also known as Raskol (russian: раскол, , meaning "split" or " schism"), was the splitting of the

The Raskol (schism) still exists, and with it a certain antagonism between the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate and the Old Believers, although on an official level both sides have agreed on a peaceful coexistence. From an ecclesiastic and theological point of view the Raskol remains a highly controversial question and one of the most tragic episodes of Russian history.

The Raskol (schism) still exists, and with it a certain antagonism between the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate and the Old Believers, although on an official level both sides have agreed on a peaceful coexistence. From an ecclesiastic and theological point of view the Raskol remains a highly controversial question and one of the most tragic episodes of Russian history.

Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

into an official church and the Old Believers

Old Believers or Old Ritualists, ''starovery'' or ''staroobryadtsy'' are Eastern Orthodox Christians who maintain the liturgical and ritual practices of the Russian Orthodox Church as they were before the reforms of Patriarch Nikon of Moscow bet ...

movement in the mid-17th century. It was triggered by the reforms of Patriarch Nikon

Nikon ( ru , Ни́кон, Old Russian: ''Нїконъ''), born Nikita Minin (''Никита Минин''; 7 May 1605 – 17 August 1681) was the seventh Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus' of the Russian Orthodox Church, serving officially from ...

in 1653, which aimed to establish uniformity between Greek and Russian church practices.

Church reforms and reaction to them

The members of an influential circle called the Zealots of Piety (Russian: Кружок ревнителей благочестия, ''Kruzhok revnitelei blagochestiya'') stood for purification of Russian Orthodox faith. They strove to reformMuscovite

Muscovite (also known as common mica, isinglass, or potash mica) is a hydrated phyllosilicate mineral of aluminium and potassium with formula K Al2(Al Si3 O10)( F,O H)2, or ( KF)2( Al2O3)3( SiO2)6( H2O). It has a highly perfect basal cleavag ...

society, bringing it into closer accordance with Christian values and to improve church practices. As a consequence, they also were engaged in the removal of alternative versions and correction of divine service books. The most influential members of this circle were Archpriest

The ecclesiastical title of archpriest or archpresbyter belongs to certain priests with supervisory duties over a number of parishes. The term is most often used in Eastern Orthodoxy and the Eastern Catholic Churches and may be somewhat analogous ...

s Avvakum

Avvakum Petrov (russian: link=no, Аввакум Петров; 20 November 1620/21 – 14 April 1682) (also spelled Awakum) was an Old Believer and Russian protopope of the Kazan Cathedral on Red Square who led the opposition to Patriarch N ...

, Ivan Neronov, Stephan Vonifatiyev, Fyodor Rtishchev

Feodor Mikhailovich Rtishchev (russian: Фёдор Миха́йлович Рти́щев; April 16, 1625, Chekalinsky uyezd – July 1, 1673, Moscow) was a boyar and an intimate friend of Alexis I of Russia who was renowned for his piety and alms ...

and, when still Archbishop of Novgorod

The Diocese of Novgorod (russian: Новгородская епархия) is one of the oldest offices in the Russian Orthodox Church. The medieval archbishops of Novgorod were among the most important figures in medieval Russian history and cul ...

, Nikon himself, the future Patriarch.

With the support from the Russian Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East Slavs, East and South Slavs, South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''Caesar (title), caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" i ...

Alexei Mikhailovich

Aleksey Mikhaylovich ( rus, Алексе́й Миха́йлович, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪtɕ; – ) was the Tsar of Russia from 1645 until his death in 1676. While finding success in foreign affairs, his reign saw several wars ...

, Patriarch Nikon began the process of correction of the Russian divine service books in accordance with their modern Greek counterparts and changed some of the rituals (the two-finger sign of the cross

Making the sign of the cross ( la, signum crucis), or blessing oneself or crossing oneself, is a ritual blessing made by members of some branches of Christianity. This blessing is made by the tracing of an upright cross or + across the body with ...

was replaced by the one with three fingers, "hallelujah

''Hallelujah'' ( ; he, ''haləlū-Yāh'', meaning "praise Yah") is an interjection used as an expression of gratitude to God. The term is used 24 times in the Hebrew Bible (in the book of Psalms), twice in deuterocanonical books, and four tim ...

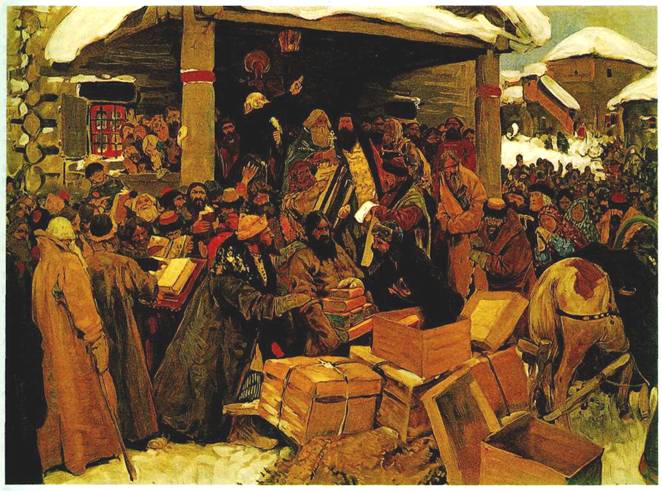

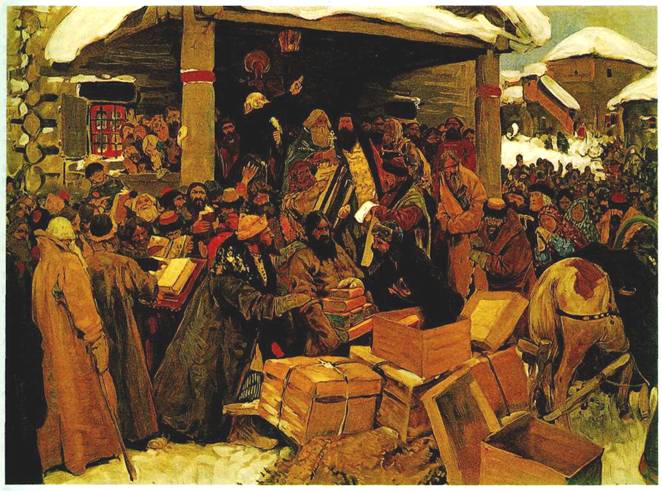

" was to be pronounced three times instead of two etc.). These innovations met with resistance from both the clergy and the people, who disputed the legitimacy and correctness of these reforms, referring to theological traditions and Eastern Orthodox ecclesiastic rules. Ignoring these protests, the reforms were approved by the church sobors in 1654–1655. In 1653–1656, the Print Yard

The Moscow Print Yard (russian: Московский Печатный двор) was the first publishing house in Russia. It was established in Kitai-gorod at the behest of Ivan the Terrible in 1553. The historic headquarters of the Print Yard no ...

under Epifany Slavinetsky began to produce corrected versions of newly translated divine service books.

A traditional, widespread view of these reforms is that they only affected the external ritualistic side of the Russian Orthodox faith and that these changes were deemed a major event by the religious Russian people

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 ''Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

. However, these reforms, apart from their arbitrariness, established radically different relations between the church and the faithful. It soon became obvious that Nikon had used this reform for the purpose of centralization of the church and strengthening of his own authority. Nikon's forcible introduction of the new divine service books and rituals caused a major estrangement between the Zealots of Piety and Nikon. Some of its members stood up for the old faith (''staroobryadsty'' : Old Ritualists) and opposed the reforms and patriarch's actions.

Avvakum and Daniel first petitioned to the tsar to officialize the two-finger sign of the cross and bows during divine services and sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. El ...

s. Then, they tried to prove to the clergy that the correction of the books in accordance with the Greek standards profaned the pure faith because the Greek Church had deviated from the "ancient piety" and had been printing its divine service books in Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

print houses and that they had been exposed to Roman Catholic influences. Ivan Neronov spoke against the strengthening of patriarch's authority and demanded democratization

Democratization, or democratisation, is the transition to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction. It may be a hybrid regime in transition from an authoritarian regime to a ful ...

of ecclesiastic management. This conflict between Nikon and defenders of the old faith took a turn for the worse and soon Avvakum, Ivan Neronov and others would be persecuted and eventually executed in 1682.

The case brought by the defenders of the old faith found many supporters among different strata of the Russian society, which would give birth to the Raskol movement. A part of the old faith low-ranking clergy protested against the increase of feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a wa ...

oppression, coming from the church leaders. Some members of the high-ranking clergy joined the Raskol movement due to their discontent over Nikon's aspirations and the arbitrariness of his church reforms.

Some of them, such as Bishop Paul of Kolomna

Paul of Kolomna (Павел Коломенский) was a 17th-century Russian prelate and martyr in the view of the Old Believers.

The son of a rural clergyman, he was born in the village of Kolychevo, Nizhny Novgorod Oblast. He entered monastic ...

, Archbishop Alexander of Vyatka

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

(as well as a number of monasteries, such as the famous Solovetsky Monastery

The Solovetsky Monastery ( rus, Солове́цкий монасты́рь, p=səlɐˈvʲɛtskʲɪj mənɐˈstɨrʲ) is a fortified monastery located on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea in northern Russia. It was one of the largest Chris ...

), stood up for the old faith; bishop Paul was eventually executed for his loyalty to the old rites. Boyarynya Feodosiya Morozova

Feodosia Prokopiyevna Morozova (russian: link=no, Феодосия Прокопьевна Морозова; 21 May 1632 – 1 December 1675) was one of the best-known partisans of the Old Believer movement. She was perceived as a martyr after s ...

, her sister Princess Urusova, and some other courtiers openly supported or secretly sympathized with the defenders of the old faith.

The unification of such heterogeneous

Homogeneity and heterogeneity are concepts often used in the sciences and statistics relating to the uniformity of a substance or organism. A material or image that is homogeneous is uniform in composition or character (i.e. color, shape, siz ...

forces against what had become "the official church" could probably be explained by the somewhat contradictory ideology of the Raskol movement. A certain idealization and conservation of traditional values and old traditions, a critical attitude towards innovations, conservation of national originality and acceptance (by radical elements) of martyrdom

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external ...

in the name of the old faith as the only way towards salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

were intertwined with criticism of feudalism and serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

. Different social strata were attracted to different sides of this ideology.

The most radical apologists of the Raskol preached about approaching Armageddon

According to the Book of Revelation in the New Testament of the Christian Bible, Armageddon (, from grc, Ἁρμαγεδών ''Harmagedōn'', Late Latin: , from Hebrew: ''Har Məgīddō'') is the prophesied location of a gathering of armies ...

and coming of the Antichrist

In Christian eschatology, the Antichrist refers to people prophesied by the Bible to oppose Jesus Christ and substitute themselves in Christ's place before the Second Coming. The term Antichrist (including one plural form) 1 John ; . 2 John . ...

, Tsar's and patriarch's worshiping of Satan

Satan,, ; grc, ὁ σατανᾶς or , ; ar, شيطانالخَنَّاس , also known as Devil in Christianity, the Devil, and sometimes also called Lucifer in Christianity, is an non-physical entity, entity in the Abrahamic religions ...

, which ideas would find a broad response among the Russian people, sympathizing with the ideology of these most radical apologetes. The Raskol movement thus became a vanguard of the conservative and at the same time democratic opposition.

Uprisings and persecution

The Raskol movement gained in strength after the church sobor in 1666–67, which had anathemized the defenders of the old faith (''staroobryadsty'' : Old Ritualists) as heretics and made decisions with regards to their punishment. Especially members of the low-ranking clergy, who had severed their relations with the church, became the leaders of the opposition. Propagation of the split with the church in the name of preservation of the Orthodox faith as it had existed until the reforms was the main postulate of their ideology. The most dramatic manifestations of the Raskol included the practice of the so-called ''ognenniye kreshcheniya'' (огненные крещения, orbaptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

by fire), or self-immolation

The term self-immolation broadly refers to acts of altruistic suicide, otherwise the giving up of one's body in an act of sacrifice. However, it most often refers specifically to autocremation, the act of sacrificing oneself by setting oneself o ...

, practiced by the most radical elements in the Old Believers' movement, who thought that the end of the world was near.

The Old Believers would soon split into different denominations, the Popovtsy

The Popovtsy ( rus, поповцы, p=pɐˈpoft͡sɨ, "priested ones") or Popovschina (russian: поповщина) were from the 17th century one of the two main factions of Old Believers, along with the Bezpopovtsy ("priestless ones").

Historica ...

and the Bespopovtsy

Bespopovtsy ( rus, беспоповцы, p=bʲɪspɐˈpoft͡sɨ, "priestless ones") are Priestless Old Believers that reject Nikonite priests. They are one of the two major strains of Old Believers.

Priestless Old Believers may have evolved into ...

. Attracted to the preachings of the Raskol ideologists, many posad

A posad (russian: посад, uk, посад) was a historical type of settlement in East Slavic lands since the Ancient Rus, often surrounded by ramparts and a moat, adjoining a town or a kremlin, but outside of it, or adjoining a monastery ...

people, mainly peasants, craftsmen and cossacks fled to the dense forests of Northern Russia and Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the List of rivers of Europe#Rivers of Europe by length, longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Cas ...

region, southern borders of Russia, Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

, and even abroad, where they would organize their own obshchina

Obshchina ( rus, община, p=ɐpˈɕːinə, literally "commune") or mir (russian: мир, literally "society", among other meanings), or selskoye obshchestvo (russian: сельское общество, literally "rural community", official ...

s. This was a mass exodus of common Russian people, who had refused to follow the new ecclesiastic rituals. In 1681, the government noted an increase among the "enemies of the church", especially in Siberia. With active support from the Russian Orthodox Church, it began to persecute the so-called ''raskolniki'' (раскольники), i.e., "schism-makers".

In the 1670s–1680s, the exposure of certain social vices in the Russian society gained special importance in the Raskol ideology. Some of the Raskol apologetes, such as Avvakum and his brothers-in-exile at the Pustozyorsk

Pustozersk (russian: Пустозерск , Tundra Nenets: Санэр” харад, ''Sadėr’’ harad'') or Pustozyorsk () was the first town built by Russians north of the Arctic Circle. It was the administrative center of Yugra and Pecho ...

prison, tended to justify some of the uprisings, interpreting them as God's punishment of the ecclesiastic and tsarist authorities for their actions. Some of the supporters of the Old Believers took part in Stepan Razin's rebellion in 1670–1671, although this uprising is not regarded as an Old Believers' rebellion and Stenka Razin himself had strongly antiecclesiastic views. The supporters of the old faith played an important role in the Moscow uprising of 1682

The Moscow uprising of 1682, also known as the Streltsy uprising of 1682 (russian: Стрелецкий бунт), was an uprising of the Moscow Streltsy regiments that resulted in supreme power devolving on Sophia Alekseyevna (the daughter of th ...

. Many of the members of the old faith migrated west, seeking refuge in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

, which allowed them to practice their faith freely.

In the late 17th – early 18th century, the most radical elements of the Raskol movement went into recession after it had become obvious that the reforms could not be reversed. The internal policy of Peter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

eased the persecution of the Old Believers. The Tsar, however, did impose higher taxes on them. During the reign of Catherine the Great, Old Believers who had fled abroad were even encouraged to return to their motherland. However, the position of Old Believers in Russia remained illegal until 1905.

The Raskol (schism) still exists, and with it a certain antagonism between the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate and the Old Believers, although on an official level both sides have agreed on a peaceful coexistence. From an ecclesiastic and theological point of view the Raskol remains a highly controversial question and one of the most tragic episodes of Russian history.

The Raskol (schism) still exists, and with it a certain antagonism between the Russian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate and the Old Believers, although on an official level both sides have agreed on a peaceful coexistence. From an ecclesiastic and theological point of view the Raskol remains a highly controversial question and one of the most tragic episodes of Russian history.

Literary reference

The term is etymologically related to the family name ofRodion Raskolnikov

Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform rus, Родион Романович Раскольников, Rodión Románovich Raskólʹnikov, rədʲɪˈon rɐˈmanəvʲɪtɕ rɐˈskolʲnʲɪkəf) is the fictional protag ...

, the protagonist of Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

's well-known novel ''Crime and Punishment

''Crime and Punishment'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform rus, Преступление и наказание, Prestupléniye i nakazániye, prʲɪstʊˈplʲenʲɪje ɪ nəkɐˈzanʲɪje) is a novel by the Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky. ...

''.

See also

*Patriarch Nikon of Moscow

Nikon ( ru , Ни́кон, Old Russian: ''Нїконъ''), born Nikita Minin (''Никита Минин''; 7 May 1605 – 17 August 1681) was the seventh Patriarch of Moscow and all Rus' of the Russian Orthodox Church, serving officially from ...

*Old Believers

Old Believers or Old Ritualists, ''starovery'' or ''staroobryadtsy'' are Eastern Orthodox Christians who maintain the liturgical and ritual practices of the Russian Orthodox Church as they were before the reforms of Patriarch Nikon of Moscow bet ...

*Edinoverie Edinoverie ( rus, единове́рие, p=jɪdʲɪnɐˈvʲerʲɪjɪ, literally “coreligionism”) is an arrangement between certain Russian Old Believer communities and the official Russian Orthodox Church, whereby such communities are treated a ...

*Avvakum

Avvakum Petrov (russian: link=no, Аввакум Петров; 20 November 1620/21 – 14 April 1682) (also spelled Awakum) was an Old Believer and Russian protopope of the Kazan Cathedral on Red Square who led the opposition to Patriarch N ...

References

In English

* . * . * . * . * . * . * * .In Russian

* . * . * * . * . * . * . * . * . {{Authority control Old Believer movement Schisms in Christianity Schisms from the Eastern Orthodox Church Religion in Russia 17th-century Eastern Orthodoxy 17th century in Russia de:Raskolniken ja:ラスコーリニキ