Ramesses III on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Usermaatre Meryamun Ramesses III (also written Ramses and Rameses) was the second

During his long tenure in the midst of the surrounding political chaos of the Late Bronze Age collapse, Egypt was beset by foreign invaders (including the so-called

During his long tenure in the midst of the surrounding political chaos of the Late Bronze Age collapse, Egypt was beset by foreign invaders (including the so-called

It is not certain whether the assassination plot succeeded since Ramesses IV, the king's designated successor, assumed the throne upon his death rather than Pentaweret, who was intended to be the main beneficiary of the palace conspiracy. Moreover, Ramesses III died in his 32nd year before the summaries of the sentences were composed, but the same year that the trial documents record the trial and execution of the conspirators.

It is not certain whether the assassination plot succeeded since Ramesses IV, the king's designated successor, assumed the throne upon his death rather than Pentaweret, who was intended to be the main beneficiary of the palace conspiracy. Moreover, Ramesses III died in his 32nd year before the summaries of the sentences were composed, but the same year that the trial documents record the trial and execution of the conspirators.

Although it was long believed that Ramesses III's body showed no obvious wounds, a recent examination of the mummy by a German forensic team, televised in the documentary ''Ramesses: Mummy King Mystery'' on the Science Channel in 2011, showed excessive bandages around the neck. A subsequent CT scan that was done in Egypt by Ashraf Selim and

Although it was long believed that Ramesses III's body showed no obvious wounds, a recent examination of the mummy by a German forensic team, televised in the documentary ''Ramesses: Mummy King Mystery'' on the Science Channel in 2011, showed excessive bandages around the neck. A subsequent CT scan that was done in Egypt by Ashraf Selim and

. Retrieved 2012-12-18. Zink observes in an interview that: :The cut o Ramesses III's throatis...very deep and quite large, it really goes down almost down to the bone (spine) - it must have been a lethal injury. A subsequent study of the CT scan of the mummy of Ramesses III's body by Sahar Saleem revealed that the left big toe was likely chopped by a heavy sharp object like an ax. There were no signs of bone healing so this injury must have happened shortly before death. The embalmers placed a prosthesis-like object made of linen in place of the amputated toe. The embalmers placed six amulets around both feet and ankles for magical healing of the wound for the life after. This additional injury of the foot supports the assassination of the Pharaoh, likely by the hands of multiple assailants using different weapons. Before this discovery it had been speculated that Ramesses III had been killed by means that would not have left a mark on the body. Among the conspirators were practitioners of magic, who might well have used poison. Some had put forth a hypothesis that a snakebite from a

TOWARDS A HOLOCENE TEPHROCHRONOLOGY FOR SWEDEN

, Stefan Wastegǎrd, XVI INQUA Congress, Paper No. 41-13, Saturday, July 26, 2003. Also

Late Holocene solifluction history reconstructed using tephrochronology

, Martin P. Kirkbride & Andrew J. Dugmore, Geological Society, London, Special Publications; 2005; v. 242; p. 145-155. Given that no Egyptologist dates Ramesses III's reign to as late as 1000 BC, this would mean that the Hekla 3 eruption presumably occurred well after Ramesses III's reign. A 2002 study, using high-precision radiocarbon dating of a peat deposit containing ash layers, put this eruption in the range 1087–1006 BC.

File:Ramses III mummy head.png, Ramesses III's mummy

File:KhonsuTemple-Karnak-Incredible.jpg, Finely painted reliefs from Ramesses III's Khonsu temple at Karnak

File:PalaceInlays-NubiansPhilistineAmoriteSyrianAndHittite-Compilation-MuseumOfFineArtsBoston.png, Ramesses III prisoner tiles: Inlay figures, faience and glass, of "the traditional enemies of Ancient Egypt" from Medinet Habu, at the

Timna: Valley of the Ancient Copper Mines

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ramesses 03 12th-century BC Pharaohs Pharaohs of the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt Ancient Egyptian mummies Sea Peoples 1217 BC births 1155 BC deaths Ancient murdered monarchs 12th-century BC murdered monarchs Late Bronze Age collapse Deaths by stabbing in Egypt

Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: ''pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the an ...

of the Twentieth Dynasty

The Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XX, alternatively 20th Dynasty or Dynasty 20) is the third and last dynasty of the Ancient Egyptian New Kingdom period, lasting from 1189 BC to 1077 BC. The 19th and 20th Dynasties furthermore togeth ...

in Ancient Egypt. He is thought to have reigned from 26 March 1186 to 15 April 1155 BC and is considered to be the last great monarch of the New Kingdom to wield any substantial authority over Egypt. His long reign saw the decline of Egyptian political and economic power, linked to a series of invasions and internal economic problems that also plagued pharaohs before him. This coincided with a decline in the cultural sphere of Ancient Egypt. However, his successful defense was able to slow down the decline, although it still meant that his successors would have a weaker military. He has also been described as a "warrior Pharaoh" due to his strong military strategies. He led the way by defeating the invaders known as "the Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are a hypothesized seafaring confederation that attacked ancient Egypt and other regions in the East Mediterranean prior to and during the Late Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BCE).. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the Fren ...

", who had caused destruction in other civilizations and empires. He was able to save Egypt from collapsing at the time when many other empires fell during the Late Bronze Age; however, the damage of the invasions took a toll on Egypt. Rameses III constructed one of the largest mortuary temples of western Thebes, now-called Medinet Habu.

Ramesses III was the son of Setnakhte

Userkhaure-setepenre Setnakhte (also called Setnakht or Sethnakht) was the first pharaoh ( 1189 BC– 1186 BC) of the Twentieth Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt and the father of Ramesses III.

Accession

Setnakhte was not the son ...

and Tiy-Merenese. He was assassinated in the Harem conspiracy

The Harem conspiracy was a plot to assassinate the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses III in 1155 BC. The principal figure behind the plot was one of the pharaoh's secondary wives, Tiye, who hoped to place her son Pentawer on the throne instead of the p ...

led by his secondary wife Tiye

Tiye (c. 1398 BC – 1338 BC, also spelled Tye, Taia, Tiy and Tiyi) was the daughter of Yuya and Thuya. She became the Great Royal Wife of the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III. She was the mother of Akhenaten and grandmother of Tutankhamun. ...

and her eldest son Pentawere. This would ultimately cause a succession crisis which would further accelerate the decline of Ancient Egypt. He was succeeded by his son Ramesses IV

Heqamaatre Setepenamun Ramesses IV (also written Ramses or Rameses) was the third pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt. He was the second son of Ramesses III and became crown prince when his elder brother Amenhe ...

, although many of his other sons would rule later.

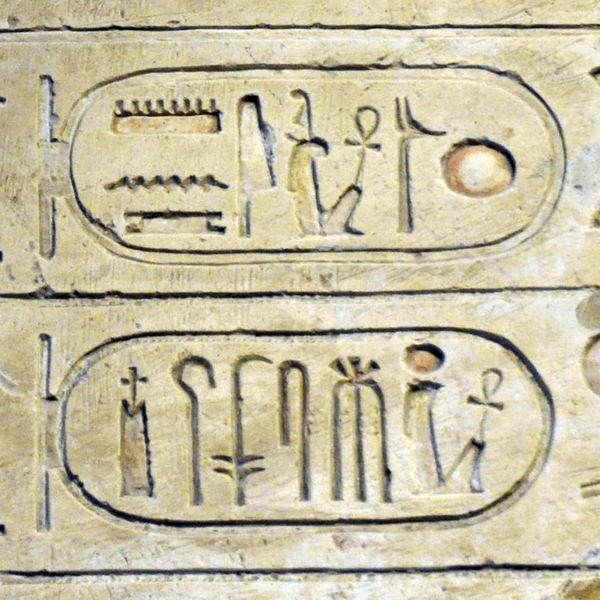

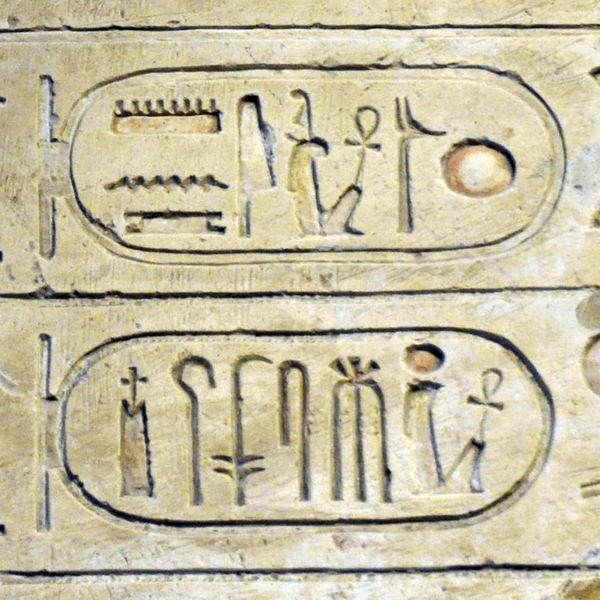

Name

Ramesses' two main names transliterate as wsr-mꜢʿt-rʿ–mry-ỉmn rʿ-ms-s–ḥḳꜢ-ỉwnw. They are normally realised as ''Usermaatre-Meryamun Rameses-Heqaiunu'', meaning "TheMa'at

Maat or Maʽat ( Egyptian:

mꜣꜥt /ˈmuʀʕat/, Coptic: ⲙⲉⲓ) refers to the ancient Egyptian concepts of truth, balance, order, harmony, law, morality, and justice. Ma'at was also the goddess who personified these concepts, and regul ...

of Ra is strong, Beloved of Amun, Born of Ra, Ruler of Heliopolis".

Ascension

Ramesses III is believed to have reigned from March 1186 to April 1155 BC. This is based on his known accession date of I Shemu day 26 and his death on Year 32 III Shemu day 15, for a reign of 31 years, 1 month and 19 days. Alternative dates for his reign are 1187–1156 BC. In a description of hiscoronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of ot ...

from Medinet Habu, four dove

Columbidae () is a bird family consisting of doves and pigeons. It is the only family in the order Columbiformes. These are stout-bodied birds with short necks and short slender bills that in some species feature fleshy ceres. They primarily ...

s were said to be "dispatched to the four corners of the horizon to confirm that the living Horus

Horus or Heru, Hor, Har in Ancient Egyptian, is one of the most significant ancient Egyptian deities who served many functions, most notably as god of kingship and the sky. He was worshipped from at least the late prehistoric Egypt until the P ...

, Ramses III, is (still) in possession of his throne, that the order of Maat

Maat or Maʽat ( Egyptian:

mꜣꜥt /ˈmuʀʕat/, Coptic: ⲙⲉⲓ) refers to the ancient Egyptian concepts of truth, balance, order, harmony, law, morality, and justice. Ma'at was also the goddess who personified these concepts, and regul ...

prevails in the cosmos and society".

Tenure of constant war

During his long tenure in the midst of the surrounding political chaos of the Late Bronze Age collapse, Egypt was beset by foreign invaders (including the so-called

During his long tenure in the midst of the surrounding political chaos of the Late Bronze Age collapse, Egypt was beset by foreign invaders (including the so-called Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are a hypothesized seafaring confederation that attacked ancient Egypt and other regions in the East Mediterranean prior to and during the Late Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BCE).. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the Fren ...

and the Libyans) and experienced the beginnings of increasing economic difficulties and internal strife which would eventually lead to the collapse of the Twentieth Dynasty. In Year 8 of his reign, the Sea Peoples, including Peleset

The Peleset ( Egyptian: ''pwrꜣsꜣtj'') or Pulasati were one of the several ethnic groups the Sea Peoples were said to be composed of, appearing in fragmentary historical and iconographic records in ancient Egyptian from the Eastern Mediterra ...

, Denyen

The Denyen ( Egyptian: ''dꜣjnjnjw'') is purported to be one of the groups constituting the Sea Peoples.

Origin

They are mentioned in the Amarna letters from the 14th century BC as possibly being related to the "Land of the Danuna" near Ugarit. ...

, Shardana

The Sherden ( Egyptian: ''šrdn'', ''šꜣrdꜣnꜣ'' or ''šꜣrdynꜣ'', Ugaritic: ''šrdnn(m)'' and ''trtn(m)'', possibly Akkadian: ''še-er-ta-an-nu''; also glossed “Shardana” or “Sherdanu”) are one of the several ethnic groups the Se ...

, Meshwesh of the sea, and Tjekker

The Tjeker or Tjekker (Egyptian language, Egyptian: ''ṯꜣkꜣr'' or ''ṯꜣkkꜣr'') were one of the Sea Peoples.

Known mainly from the "Story of Wenamun", the Tjeker are also documented earlier, at Medinet Habu (temple), Medinet Habu, as raid ...

, invaded Egypt by land and sea. Ramesses III defeated them in two great land and sea battles. Although the Egyptians had a reputation as poor seamen, they fought tenaciously. Rameses lined the shores with ranks of archers who kept up a continuous volley of arrows into the enemy ships when they attempted to land on the banks of the Nile. Then, the Egyptian navy attacked using grappling hooks to haul in the enemy ships. In the brutal hand-to-hand fighting which ensued, the Sea Peoples were utterly defeated. The Harris Papyrus states:

Ramesses III incorporated the Sea Peoples as subject peoples and settled them in southern Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – ; he, כְּנַעַן – , in pausa – ; grc-bib, Χανααν – ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

. Their presence in Canaan may have contributed to the formation of new states in this region such as Philistia after the collapse of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. During the reign of Ramses III, Egyptian presence in the Levant is still attested as far as Byblos

Byblos ( ; gr, Βύβλος), also known as Jbeil or Jubayl ( ar, جُبَيْل, Jubayl, locally ; phn, 𐤂𐤁𐤋, , probably ), is a city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. It is believed to have been first occupied between 8 ...

and he may have campaigned further north into Syria. Ramesses III was also compelled to fight invading Libyan tribesmen in two major campaigns in Egypt's Western Delta in his Year 5 and Year 11 respectively. by the early 12th century, Egypt claimed overlordship of Cyrenaican tribes. At one point a ruler chosen by Egypt was set up (briefly!) over the combined tribes of Meshwesh, Libu, and Soped.

Economic turmoil

The heavy cost of these battles slowly exhausted Egypt's treasury and contributed to the gradual decline of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. The severity of these difficulties is stressed by the fact that the first known labour strike in recorded history occurred during Year 29 of Ramesses III's reign, when the food rations for the favoured and elite royal tomb-builders and artisans in the village of ''Set Maat her imenty Waset'' (now known asDeir el-Medina

Deir el-Medina ( arz, دير المدينة), or Dayr al-Madīnah, is an ancient Egyptian workmen's village which was home to the artisans who worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings during the 18th to 20th Dynasties of the New Kingdom of ...

), could not be provisioned. Something in the air (possibly the Hekla 3 eruption) prevented much sunlight from reaching the ground and also arrested global tree growth for almost two full decades until 1140 BC. The result in Egypt was a substantial increase in grain prices under the later reigns of Ramesses VI-VII, whereas the prices for fowl and slaves remained constant. Thus the cooldown affected Ramesses III's final years and impaired his ability to provide a constant supply of grain rations to the workmen of the Deir el-Medina community.

These difficult realities are completely ignored in Ramesses' official monuments, many of which seek to emulate those of his famous predecessor, Ramesses II

Ramesses II ( egy, wikt:rꜥ-ms-sw, rꜥ-ms-sw ''Rīʿa-məsī-sū'', , meaning "Ra is the one who bore him"; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Along with Thutmose III he is oft ...

, and which present an image of continuity and stability. He built important additions to the temples

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

at Luxor

Luxor ( ar, الأقصر, al-ʾuqṣur, lit=the palaces) is a modern city in Upper (southern) Egypt which includes the site of the Ancient Egyptian city of ''Thebes''.

Luxor has frequently been characterized as the "world's greatest open-a ...

and Karnak

The Karnak Temple Complex, commonly known as Karnak (, which was originally derived from ar, خورنق ''Khurnaq'' "fortified village"), comprises a vast mix of decayed temples, pylons, chapels, and other buildings near Luxor, Egypt. Constr ...

, and his funerary temple and administrative complex at Medinet-Habu is amongst the largest and best-preserved in Egypt; however, the uncertainty of Ramesses' times is apparent from the massive fortifications which were built to enclose the latter. No temple in the heart of Egypt prior to Ramesses' reign had ever needed to be protected in such a manner.

Conspiracy and death

Thanks to the discovery ofpapyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, '' Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'') can also refer to a ...

trial transcripts (dated to Ramesses III), it is now known that there was a plot against his life as a result of a royal harem conspiracy

The Harem conspiracy was a plot to assassinate the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses III in 1155 BC. The principal figure behind the plot was one of the pharaoh's secondary wives, Tiye, who hoped to place her son Pentawer on the throne instead of the p ...

during a celebration at Medinet Habu. The conspiracy was instigated by Tiye

Tiye (c. 1398 BC – 1338 BC, also spelled Tye, Taia, Tiy and Tiyi) was the daughter of Yuya and Thuya. She became the Great Royal Wife of the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III. She was the mother of Akhenaten and grandmother of Tutankhamun. ...

, one of his three known wives (the others being Tyti

Tyti was an ancient Egyptian queen of the 20th Dynasty. A wife and sister of Ramesses III and possibly the mother of Ramesses IV.

Place of Tyti in the 20th Dynasty

It was once uncertain which pharaoh was her husband, but he can now be identifie ...

and Iset Ta-Hemdjert

Iset Ta-Hemdjert or Isis Ta-Hemdjert, simply called Isis in her tomb, was an ancient Egyptian queen of the Twentieth Dynasty; the Great Royal Wife of Ramesses III and the Royal Mother of Ramesses VI., pp.186-187

She was probably of Asian ori ...

), over whose son would inherit the throne. Tyti's son, Ramesses Amenherkhepshef (the future Ramesses IV

Heqamaatre Setepenamun Ramesses IV (also written Ramses or Rameses) was the third pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt. He was the second son of Ramesses III and became crown prince when his elder brother Amenhe ...

), was the eldest and the successor chosen by Ramesses III in preference to Tiye's son Pentaweret.

The trial documentsJ. H. Breasted, ''Ancient Records of Egypt'', Part Four, §§423-456 show that many individuals were implicated in the plot. Chief among them were Queen Tiye

Tiye (c. 1398 BC – 1338 BC, also spelled Tye, Taia, Tiy and Tiyi) was the daughter of Yuya and Thuya. She became the Great Royal Wife of the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III. She was the mother of Akhenaten and grandmother of Tutankhamun. ...

and her son Pentaweret, Ramesses' chief of the chamber, Pebekkamen Pebekkamen was an ancient Egyptian official during the reign of pharaoh Ramesses III of the 20th Dynasty. Along with Ramesses' secondary wife Tiye and the official Mesedsure, he was a primary organizer of the Harem conspiracy in 1155 BC.James Henr ...

, seven royal butlers (a respectable state office), two Treasury overseers, two Army standard bearers, two royal scribes and a herald. There is little doubt that all of the main conspirators were executed: some of the condemned were given the option of committing suicide (possibly by poison) rather than being put to death. According to the surviving trial transcripts, a total of three separate trials were started, while 38 people were sentenced to death. The tombs of Tiye and her son Pentaweret were robbed and their names erased to prevent them from enjoying an afterlife. The Egyptians did such a thorough job of this that the only references to them are the trial documents and what remains of their tombs.

Some of the accused harem women tried to seduce the members of the judiciary who tried them but were caught in the act. Judges who were involved were severely punished.''Cambridge Ancient History'', Cambridge University Press 2000, p.247

It is not certain whether the assassination plot succeeded since Ramesses IV, the king's designated successor, assumed the throne upon his death rather than Pentaweret, who was intended to be the main beneficiary of the palace conspiracy. Moreover, Ramesses III died in his 32nd year before the summaries of the sentences were composed, but the same year that the trial documents record the trial and execution of the conspirators.

It is not certain whether the assassination plot succeeded since Ramesses IV, the king's designated successor, assumed the throne upon his death rather than Pentaweret, who was intended to be the main beneficiary of the palace conspiracy. Moreover, Ramesses III died in his 32nd year before the summaries of the sentences were composed, but the same year that the trial documents record the trial and execution of the conspirators.

Although it was long believed that Ramesses III's body showed no obvious wounds, a recent examination of the mummy by a German forensic team, televised in the documentary ''Ramesses: Mummy King Mystery'' on the Science Channel in 2011, showed excessive bandages around the neck. A subsequent CT scan that was done in Egypt by Ashraf Selim and

Although it was long believed that Ramesses III's body showed no obvious wounds, a recent examination of the mummy by a German forensic team, televised in the documentary ''Ramesses: Mummy King Mystery'' on the Science Channel in 2011, showed excessive bandages around the neck. A subsequent CT scan that was done in Egypt by Ashraf Selim and Sahar Saleem

Sahar Saleem is a professor of radiology at Cairo University where she specialises in paleoradiology, the use of radiology to study mummies. She discovered the knife wound in the throat of Ramesses III, which was most likely the cause of his deat ...

, professors of Radiology in Cairo University, revealed that beneath the bandages was a deep knife wound across the throat, deep enough to reach the vertebrae. According to the documentary narrator, "It was a wound no one could have survived." The December 2012 issue of the British Medical Journal quotes the conclusion of the study of the team of researchers, led by Zahi Hawass

Zahi Abass Hawass ( ar, زاهي حواس; born May 28, 1947) is an Egyptian archaeologist, Egyptologist, and former Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs, serving twice. He has also worked at archaeological sites in the Nile Delta, the Wes ...

, the former head of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquity, and his Egyptian team, as well as Albert Zink from the Institute for Mummies and the Iceman of the Eurac Research

Eurac Research is a private research center headquartered in Bolzano, South Tyrol. The center has eleven institutes and five centers. Eurac Research has more than 800 partners spread across 56 countries. Eurac Research collaborates with internatio ...

in Bolzano, Italy, which stated that conspirators murdered pharaoh Ramesses III by cutting his throat.King Ramesses III's throat was slit, analysis reveals. Retrieved 2012-12-18. Zink observes in an interview that: :The cut o Ramesses III's throatis...very deep and quite large, it really goes down almost down to the bone (spine) - it must have been a lethal injury. A subsequent study of the CT scan of the mummy of Ramesses III's body by Sahar Saleem revealed that the left big toe was likely chopped by a heavy sharp object like an ax. There were no signs of bone healing so this injury must have happened shortly before death. The embalmers placed a prosthesis-like object made of linen in place of the amputated toe. The embalmers placed six amulets around both feet and ankles for magical healing of the wound for the life after. This additional injury of the foot supports the assassination of the Pharaoh, likely by the hands of multiple assailants using different weapons. Before this discovery it had been speculated that Ramesses III had been killed by means that would not have left a mark on the body. Among the conspirators were practitioners of magic, who might well have used poison. Some had put forth a hypothesis that a snakebite from a

viper

The Viperidae (vipers) are a family of snakes found in most parts of the world, except for Antarctica, Australia, Hawaii, Madagascar, and various other isolated islands. They are venomous and have long (relative to non-vipers), hinged fangs tha ...

was the cause of the king's death. His mummy includes an amulet to protect Ramesses III in the afterlife from snakes. The servant in charge of his food and drink were also among the listed conspirators, but there were also other conspirators who were called the snake and the lord of snakes.

In one respect the conspirators certainly failed. The crown passed to the king's designated successor: Ramesses IV. Ramesses III may have been doubtful as to the latter's chances of succeeding him, given that, in the Great Harris Papyrus

Papyrus Harris I is also known as the Great Harris Papyrus and (less accurately) simply the Harris Papyrus (though there are a number of other papyri in the Harris collection). Its technical designation is ''Papyrus British Museum EA 9999''. At 41 ...

, he implored Amun to ensure his son's rights.

DNA and Possible relationship with his son Pentawaret

The Zink unit determined that the mummy of an unknown man buried with Ramesses was, because of the proven genetic relationship and a mummification process that suggested punishment, a good candidate for the pharaoh's son, Pentaweret, who was the only son to revolt against his father. It was impossible to determine his cause of death. Both mummies were predicted by Whit Athey's STR-predictor to share the Y chromosomal haplogroup E1b1a1-M2 and 50% of their genetic material, which pointed to a father-son relationship. In 2010 Hawass et al undertook detailed anthropological, radiological, and genetic studies as part of the King Tutankhamun Family Project. The objectives included attempting to determine familial relationships among 11 royal mummies of the New Kingdom, as well to research for pathological features including potential inherited disorders and infectious diseases. In 2012, Hawass et al undertook an anthropological, forensic, radiological, and genetic study of the 20th dynasty mummies of Ramesses III and an unknown man which were found together. In 2022, S.O.Y. Keita analysed 8 Short Tandem loci (STR) data published as part of these studies by Hawass et al, using an algorithm that only has three choices: Eurasians, sub-Saharan Africans, and East Asians. Using these three options, Keita concluded that the studies showed "a majority to have an affinity with " sub-Saharan" Africans in one affinity analysis". However, Keita cautioned that this does not mean that the royal mummies “lacked other affiliations” which he argued had been obscured in typological thinking. Keita further added that different “data and algorithms might give different results” which reflects the complexity of biological heritage and the associated interpretation.Legacy

The Great Harris Papyrus orPapyrus Harris I

Papyrus Harris I is also known as the Great Harris Papyrus and (less accurately) simply the Harris Papyrus (though there are a number of other papyri in the Harris collection). Its technical designation is ''Papyrus British Museum EA 9999''. At 41 ...

, which was commissioned by his son and chosen successor Ramesses IV

Heqamaatre Setepenamun Ramesses IV (also written Ramses or Rameses) was the third pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt. He was the second son of Ramesses III and became crown prince when his elder brother Amenhe ...

, chronicles this king's vast donations of land, gold statues and monumental construction to Egypt's various temples at Piramesse, Heliopolis, Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

, Athribis

Athribis ( ar, أتريب; Greek: , from the original Egyptian ''Hut-heryib'', cop, Ⲁⲑⲣⲏⲃⲓ) was an ancient city in Lower Egypt. It is located in present-day Tell Atrib, just northeast of Benha on the hill of Kom Sidi Yusuf. The to ...

, Hermopolis

Hermopolis ( grc, Ἑρμούπολις ''Hermoúpolis'' "the City of Hermes", also ''Hermopolis Magna'', ''Hermoû pólis megálẽ'', egy, ḫmnw , Egyptological pronunciation: "Khemenu"; cop, Ϣⲙⲟⲩⲛ ''Shmun''; ar, الأشموني ...

, This

This may refer to:

* ''This'', the singular proximal demonstrative pronoun

Places

* This, or ''Thinis'', an ancient city in Upper Egypt

* This, Ardennes, a commune in France

People with the surname

* Hervé This, French culinary chemist Arts, ...

, Abydos, Coptos

Qift ( arz, قفط ; cop, Ⲕⲉϥⲧ, link=no ''Keft'' or ''Kebto''; Egyptian Gebtu; grc, Κόπτος, link=no ''Coptos'' / ''Koptos''; Roman Justinianopolis) is a small town in the Qena Governorate of Egypt about north of Luxor, situated un ...

, El Kab

El Kab (or better Elkab) is an Upper Egyptian site on the east bank of the Nile at the mouth of the Wadi Hillal about south of Luxor (ancient Thebes). El Kab was called Nekheb in the Egyptian language ( , Late Coptic: ), a name that refer ...

and various cities in Nubia. It also records that the king dispatched a trading expedition to the Land of Punt

The Land of Punt ( Egyptian: '' pwnt''; alternate Egyptological readings ''Pwene''(''t'') /pu:nt/) was an ancient kingdom known from Ancient Egyptian trade records. It produced and exported gold, aromatic resins, blackwood, ebony, ivory an ...

and quarried the copper mines of Timna in southern Canaan. Papyrus Harris I records some of Ramesses III's activities:

Ramesses began the reconstruction of the Temple of Khonsu

The Temple of Khonsu is an ancient Egyptian temple. It is located within the large Precinct of Amun-Re at Karnak, in Luxor, Egypt. The edifice is an example of an almost complete New Kingdom temple, and was originally constructed by Ramesses III ...

at Karnak

The Karnak Temple Complex, commonly known as Karnak (, which was originally derived from ar, خورنق ''Khurnaq'' "fortified village"), comprises a vast mix of decayed temples, pylons, chapels, and other buildings near Luxor, Egypt. Constr ...

from the foundations of an earlier temple of Amenhotep III and completed the Temple of Medinet Habu around his Year 12. He decorated the walls of his Medinet Habu temple with scenes of his Naval and Land battles against the Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are a hypothesized seafaring confederation that attacked ancient Egypt and other regions in the East Mediterranean prior to and during the Late Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BCE).. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the Fren ...

. This monument stands today as one of the best-preserved temples of the New Kingdom.

The mummy

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay fu ...

of Ramesses III was discovered by antiquarians in 1886 and is regarded as the prototypical Egyptian Mummy in numerous Hollywood movies. His tomb ( KV11) is one of the largest in the Valley of the Kings

The Valley of the Kings ( ar, وادي الملوك ; Late Coptic: ), also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings ( ar, وادي أبوا الملوك ), is a valley in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the 16th to 11th ...

.

In 1980, James Harris and Edward F. Wente Edward Frank Wente (born 1930) is an American professor emeritus of Egyptology and the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago.University of ChicagoNear Eastern Languages and Civilizations Retrieved on 08- ...

conducted a series of X-ray examinations on New Kingdom Pharaohs crania and skeletal remains, which included the mummified remains of Ramesses III. The analysis in general found strong similarities between the New Kingdom rulers of the 19th Dynasty and 20th Dynasty with Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymous ...

Nubian samples. The authors also noted affinities with modern Mediterranean populations of Levantine origin. Harris and Wente suggested this represented admixture as the Rammessides were of northern origin.

In April 2021 his mummy was moved from the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, known commonly as the Egyptian Museum or the Cairo Museum, in Cairo, Egypt, is home to an extensive collection of ancient Egyptian antiquities. It has 120,000 items, with a representative amount on display a ...

to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization

The National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC) is a large museum ( ) in the ancient city of Fustat, now part of Cairo, Egypt. The museum partially opened in February 2017 and will display a collection of 50,000 artefacts, presenting Egyptian ...

along with those of 17 other kings and 4 queens in an event termed the Pharaohs' Golden Parade

The Pharaohs' Golden Parade ( ar, موكب المومياوات الملكية, arz, موكب المميات الملكيه, cop, Ϯϫⲓⲛⲟⲩⲱⲛϩ ⲛ̀ⲛⲓⲫⲁⲣⲁⲱ ⲛ̀ⲛⲟⲩⲃ, Tiḏinouōnh nnipharaō nnoub) was an eve ...

.

Chronological dispute

There is uncertainty regarding the exact dates of the reign of Ramesses III. This uncertainty affects the dating of the Late Bronze/Iron Age transition in theLevant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

. This transition is defined by the appearance of Mycenaean LH IIIC:1b ( Philistine) pottery in the coastal plain of Palestine, generally assumed to correspond to the settlement of Sea Peoples there at the 8th year of Ramesses III. Radiocarbon dates and other external evidence permit this transition to be as late as 1100 BC, compared to the conventional dating of c. 1179 BC.

Some scientists have tried to establish a chronological point for this pharaoh's reign at 1159 BC, based on a 1999 dating of the Hekla 3 eruption of the Hekla volcano in Iceland. Since contemporary records show that the king experienced difficulties provisioning his workmen at Deir el-Medina

Deir el-Medina ( arz, دير المدينة), or Dayr al-Madīnah, is an ancient Egyptian workmen's village which was home to the artisans who worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings during the 18th to 20th Dynasties of the New Kingdom of ...

with supplies in his 29th Year, this dating of Hekla 3 might connect his 28th or 29th regnal year to c. 1159 BC. A minor discrepancy of one year is possible since Egypt's granaries could have had reserves to cope with at least a single bad year of crop harvests following the onset of the disaster. This implies that the king's reign would have ended just three to four years later, around 1156 or 1155 BC. A rival date of "2900 BP" (950 BC) has since been proposed by scientists based on a re-examination of the volcanic layer.At first, scholars tried to redate the event to "3000 BP"TOWARDS A HOLOCENE TEPHROCHRONOLOGY FOR SWEDEN

, Stefan Wastegǎrd, XVI INQUA Congress, Paper No. 41-13, Saturday, July 26, 2003. Also

Late Holocene solifluction history reconstructed using tephrochronology

, Martin P. Kirkbride & Andrew J. Dugmore, Geological Society, London, Special Publications; 2005; v. 242; p. 145-155. Given that no Egyptologist dates Ramesses III's reign to as late as 1000 BC, this would mean that the Hekla 3 eruption presumably occurred well after Ramesses III's reign. A 2002 study, using high-precision radiocarbon dating of a peat deposit containing ash layers, put this eruption in the range 1087–1006 BC.

Gallery

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Museum of Fine Arts (often abbreviated as MFA Boston or MFA) is an art museum in Boston, Massachusetts. It is the 20th-largest art museum in the world, measured by public gallery area. It contains 8,161 paintings and more than 450,000 works ...

. From left: 2 Nubians

Nubians () ( Nobiin: ''Nobī,'' ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the region which is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt. They originate from the early inhabitants of the central Nile valley, believed to be one of the earliest cradles of ...

, Philistine, Amorite

The Amorites (; sux, 𒈥𒌅, MAR.TU; Akkadian: 𒀀𒈬𒊒𒌝 or 𒋾𒀉𒉡𒌝/𒊎 ; he, אֱמוֹרִי, 'Ĕmōrī; grc, Ἀμορραῖοι) were an ancient Northwest Semitic-speaking people from the Levant who also occupied lar ...

, Syrian, Hittite

File:Medinet Habu Ramses III. Tempel 02.JPG, Ramesses III's mortuary temple at Medinet Habu.

File:SFEC-2010-MEDINET HABU-052.JPG, A painted ceiling of Nekhbet

Nekhbet (; also spelt Nekhebit) is an early predynastic local goddess in Egyptian mythology, who was the patron of the city of Nekheb (her name meaning ''of Nekheb''). Ultimately, she became the patron of Upper Egypt and one of the two patron d ...

at Ramesses III's mortuary temple at Medinet Habu.

File:Bas-relief at the mortuary temple of Ramesses III 17.jpg, Medinet Habu - the severed hands of the defeated enemies

File:Great Harris Papyrus, Sheet 2.jpg, Ramesses III talking with the Theban Triad

The Theban Triad is a triad of Egyptian gods most popular in the area of Thebes, Egypt.

The triad

The group consisted of Amun, his consort Mut and their son Khonsu.

They were favored by both the 18th and 25th Dynasty. At the vast Karnak Tem ...

: Amun, Mut

Mut, also known as Maut and Mout, was a mother goddess worshipped in ancient Egypt and the Kingdom of Kush in present-day North Sudan. In Meroitic, her name was pronounced mata): 𐦨𐦴. Her name means ''mother'' in the ancient Egyptian l ...

and Khonsu

Khonsu ( egy, ḫnsw; also transliterated Chonsu, Khensu, Khons, Chons or Khonshu; cop, Ϣⲟⲛⲥ, Shons) is the ancient Egyptian god of the Moon. His name means "traveller", and this may relate to the perceived nightly travel of the Moon ...

. The ‘Great Harris Papyrus’ at the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

, c. 1150 BC. Image taken from the book '' The Search for Ancient Egypt'' () by Jean Vercoutter

Jean Vercoutter (20 January 1911 – 16 July 2000) was a French Egyptologist. One of the pioneers of archaeological research into Sudan from 1953, he was Director of the Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale from 1977 to 1981.

Biography

...

.

References

Further reading

* Eric H. Cline and David O'Connor, eds. ''Ramesses III: The Life and Times of Egypt's Last Hero'' (University of Michigan Press; 2012) 560 pages; essays by scholars.External links

Timna: Valley of the Ancient Copper Mines

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ramesses 03 12th-century BC Pharaohs Pharaohs of the Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt Ancient Egyptian mummies Sea Peoples 1217 BC births 1155 BC deaths Ancient murdered monarchs 12th-century BC murdered monarchs Late Bronze Age collapse Deaths by stabbing in Egypt