Rajiform Locomotion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Fish locomotion is the various types of animal locomotion used by fish, principally by swimming. This is achieved in different groups of fish by a variety of mechanisms of propulsion, most often by wave-like lateral flexions of the fish's body and tail in water, and in various specialised fish by motions of the fins. The major forms of locomotion in fish are:

* Anguilliform, in which a wave passes evenly along a long slender body;

* Sub-carangiform, in which the wave increases quickly in amplitude towards the tail;

* Carangiform, in which the wave is concentrated near the tail, which oscillates rapidly;

* Thunniform, rapid swimming with a large powerful crescent-shaped tail; and

* Ostraciiform, with almost no oscillation except of the tail fin.

More specialized fish include movement by pectoral fins with a mainly stiff body, opposed sculling with dorsal and anal fins, as in the sunfish; and movement by propagating a wave along the long fins with a motionless body, as in the knifefish or featherbacks.

In addition, some fish can variously "walk" (i.e., crawl over land using the pectoral and pelvic fins),

Fish locomotion is the various types of animal locomotion used by fish, principally by swimming. This is achieved in different groups of fish by a variety of mechanisms of propulsion, most often by wave-like lateral flexions of the fish's body and tail in water, and in various specialised fish by motions of the fins. The major forms of locomotion in fish are:

* Anguilliform, in which a wave passes evenly along a long slender body;

* Sub-carangiform, in which the wave increases quickly in amplitude towards the tail;

* Carangiform, in which the wave is concentrated near the tail, which oscillates rapidly;

* Thunniform, rapid swimming with a large powerful crescent-shaped tail; and

* Ostraciiform, with almost no oscillation except of the tail fin.

More specialized fish include movement by pectoral fins with a mainly stiff body, opposed sculling with dorsal and anal fins, as in the sunfish; and movement by propagating a wave along the long fins with a motionless body, as in the knifefish or featherbacks.

In addition, some fish can variously "walk" (i.e., crawl over land using the pectoral and pelvic fins),

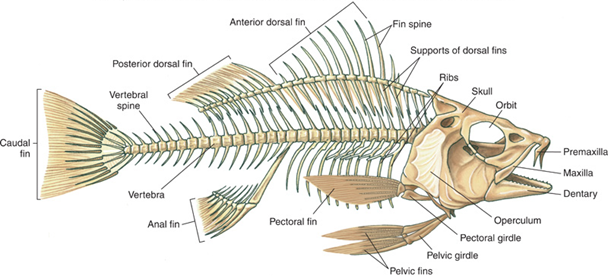

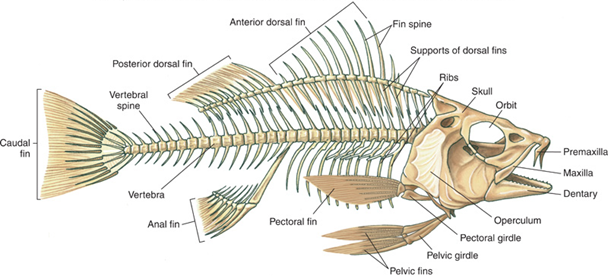

As an example of how a fish moves through the water, consider the tilapia shown in the diagram. Like most fish, the tilapia has a streamlined body shape reducing water resistance to movement and enabling the tilapia to cut easily through water. Its head is inflexible, which helps it maintain forward thrust. Its scales overlap and point backwards, allowing water to pass over the fish without unnecessary obstruction. Water friction is further reduced by mucus which tilapia secrete over their body.

As an example of how a fish moves through the water, consider the tilapia shown in the diagram. Like most fish, the tilapia has a streamlined body shape reducing water resistance to movement and enabling the tilapia to cut easily through water. Its head is inflexible, which helps it maintain forward thrust. Its scales overlap and point backwards, allowing water to pass over the fish without unnecessary obstruction. Water friction is further reduced by mucus which tilapia secrete over their body.

The backbone is flexible, allowing muscles to contract and relax rhythmically and bring about undulating movement. A

The backbone is flexible, allowing muscles to contract and relax rhythmically and bring about undulating movement. A

In the anguilliform group, containing some long, slender fish such as eels, there is little increase in the amplitude of the flexion wave as it passes along the body.

In the anguilliform group, containing some long, slender fish such as eels, there is little increase in the amplitude of the flexion wave as it passes along the body.

The thunniform group contains high-speed long-distance swimmers, and is characteristic of tunas and is also found in several lamnid sharks. Here, virtually all the sideways movement is in the tail and the region connecting the main body to the tail (the peduncle). The tail itself tends to be large and crescent shaped. This form of swimming enables these fish to chase and catch prey more easily due to the increase in speed of swimming, as in the case of barracudas.

The thunniform group contains high-speed long-distance swimmers, and is characteristic of tunas and is also found in several lamnid sharks. Here, virtually all the sideways movement is in the tail and the region connecting the main body to the tail (the peduncle). The tail itself tends to be large and crescent shaped. This form of swimming enables these fish to chase and catch prey more easily due to the increase in speed of swimming, as in the case of barracudas.

Not all fish fit comfortably in the above groups. Ocean sunfish, for example, have a completely different system, the tetraodontiform mode, and many small fish use their pectoral fins for swimming as well as for steering and dynamic lift. Fish in the order

Not all fish fit comfortably in the above groups. Ocean sunfish, for example, have a completely different system, the tetraodontiform mode, and many small fish use their pectoral fins for swimming as well as for steering and dynamic lift. Fish in the order

Diodontiform locomotion propels the fish propagating undulations along large pectoral fins, as seen in the porcupinefish ( Diodontidae).

Diodontiform locomotion propels the fish propagating undulations along large pectoral fins, as seen in the porcupinefish ( Diodontidae).

Gymnotiform locomotion consists of undulations of a long anal fin, essentially upside down amiiform, seen in the South American knifefish ''

Gymnotiform locomotion consists of undulations of a long anal fin, essentially upside down amiiform, seen in the South American knifefish ''

Bone and muscle tissues of fish are denser than water. To maintain depth, bony fish increase buoyancy by means of a

Bone and muscle tissues of fish are denser than water. To maintain depth, bony fish increase buoyancy by means of a

There are some species of fish that can "walk" along the sea floor but not on land; one such animal is the

There are some species of fish that can "walk" along the sea floor but not on land; one such animal is the

Fish larvae, like many adult fishes, swim by undulating their body. The swimming speed varies proportionally with the size of the animals, in that smaller animals tend to swim at lower speeds than larger animals. The swimming mechanism is controlled by the flow regime of the larvae.

Fish larvae, like many adult fishes, swim by undulating their body. The swimming speed varies proportionally with the size of the animals, in that smaller animals tend to swim at lower speeds than larger animals. The swimming mechanism is controlled by the flow regime of the larvae.

File:Clupeaharenguskils2.jpg,

''Fish Swimming''

Springer. . * Vogel, Steven (1994) ''Life in Moving Fluid: The Physical Biology of Flow.'' Princeton University Press. (particularly pp. 115–117 and pp. 207–216 for specific biological examples swimming and flying respectively) * Wu, Theodore, Y.-T., Brokaw, Charles J., Brennen, Christopher, Eds. (1975) ''Swimming and Flying in Nature''. Volume 2, Plenum Press. (particularly pp. 615–652 for an in depth look at fish swimming)

How fish swim: study solves muscle mystery

Simulated fish locomotion

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20110724192433/http://www.geol.umd.edu/~jmerck/bsci392/lecture10/lecture10.html The biomechanics of swimming {{fins, limbs and wings Ichthyology Aquatic locomotion Animal locomotion Articles containing video clips

Fish locomotion is the various types of animal locomotion used by fish, principally by swimming. This is achieved in different groups of fish by a variety of mechanisms of propulsion, most often by wave-like lateral flexions of the fish's body and tail in water, and in various specialised fish by motions of the fins. The major forms of locomotion in fish are:

* Anguilliform, in which a wave passes evenly along a long slender body;

* Sub-carangiform, in which the wave increases quickly in amplitude towards the tail;

* Carangiform, in which the wave is concentrated near the tail, which oscillates rapidly;

* Thunniform, rapid swimming with a large powerful crescent-shaped tail; and

* Ostraciiform, with almost no oscillation except of the tail fin.

More specialized fish include movement by pectoral fins with a mainly stiff body, opposed sculling with dorsal and anal fins, as in the sunfish; and movement by propagating a wave along the long fins with a motionless body, as in the knifefish or featherbacks.

In addition, some fish can variously "walk" (i.e., crawl over land using the pectoral and pelvic fins),

Fish locomotion is the various types of animal locomotion used by fish, principally by swimming. This is achieved in different groups of fish by a variety of mechanisms of propulsion, most often by wave-like lateral flexions of the fish's body and tail in water, and in various specialised fish by motions of the fins. The major forms of locomotion in fish are:

* Anguilliform, in which a wave passes evenly along a long slender body;

* Sub-carangiform, in which the wave increases quickly in amplitude towards the tail;

* Carangiform, in which the wave is concentrated near the tail, which oscillates rapidly;

* Thunniform, rapid swimming with a large powerful crescent-shaped tail; and

* Ostraciiform, with almost no oscillation except of the tail fin.

More specialized fish include movement by pectoral fins with a mainly stiff body, opposed sculling with dorsal and anal fins, as in the sunfish; and movement by propagating a wave along the long fins with a motionless body, as in the knifefish or featherbacks.

In addition, some fish can variously "walk" (i.e., crawl over land using the pectoral and pelvic fins), burrow

An Eastern chipmunk at the entrance of its burrow

A burrow is a hole or tunnel excavated into the ground by an animal to construct a space suitable for habitation or temporary refuge, or as a byproduct of locomotion. Burrows provide a form of sh ...

in mud, leap out of the water and even glide temporarily through the air.

Swimming

Fish swim by exerting force against the surrounding water. There are exceptions, but this is normally achieved by the fish contractingmuscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of muscl ...

s on either side of its body in order to generate waves of flexion that travel the length of the body from nose to tail, generally getting larger as they go along. The vector force

In physics, a force is an influence that can change the motion of an object. A force can cause an object with mass to change its velocity (e.g. moving from a state of rest), i.e., to accelerate. Force can also be described intuitively as a p ...

s exerted on the water by such motion cancel out laterally, but generate a net force backwards which in turn pushes the fish forward through the water. Most fishes generate thrust using lateral movements of their body and caudal fin, but many other species move mainly using their median and paired fins. The latter group swim slowly, but can turn rapidly, as is needed when living in coral reefs for example. But they can't swim as fast as fish using their bodies and caudal fins.

Example

As an example of how a fish moves through the water, consider the tilapia shown in the diagram. Like most fish, the tilapia has a streamlined body shape reducing water resistance to movement and enabling the tilapia to cut easily through water. Its head is inflexible, which helps it maintain forward thrust. Its scales overlap and point backwards, allowing water to pass over the fish without unnecessary obstruction. Water friction is further reduced by mucus which tilapia secrete over their body.

As an example of how a fish moves through the water, consider the tilapia shown in the diagram. Like most fish, the tilapia has a streamlined body shape reducing water resistance to movement and enabling the tilapia to cut easily through water. Its head is inflexible, which helps it maintain forward thrust. Its scales overlap and point backwards, allowing water to pass over the fish without unnecessary obstruction. Water friction is further reduced by mucus which tilapia secrete over their body.

The backbone is flexible, allowing muscles to contract and relax rhythmically and bring about undulating movement. A

The backbone is flexible, allowing muscles to contract and relax rhythmically and bring about undulating movement. A swim bladder

The swim bladder, gas bladder, fish maw, or air bladder is an internal gas-filled Organ (anatomy), organ that contributes to the ability of many bony fish (but not cartilaginous fish) to control their buoyancy, and thus to stay at their curren ...

provides buoyancy which helps the fish adjust its vertical position in the water column. A lateral line

The lateral line, also called the lateral line organ (LLO), is a system of sensory organs found in fish, used to detect movement, vibration, and pressure gradients in the surrounding water. The sensory ability is achieved via modified epithelial ...

system allows it to detect vibrations and pressure changes in water, helping the fish to respond appropriately to external events.

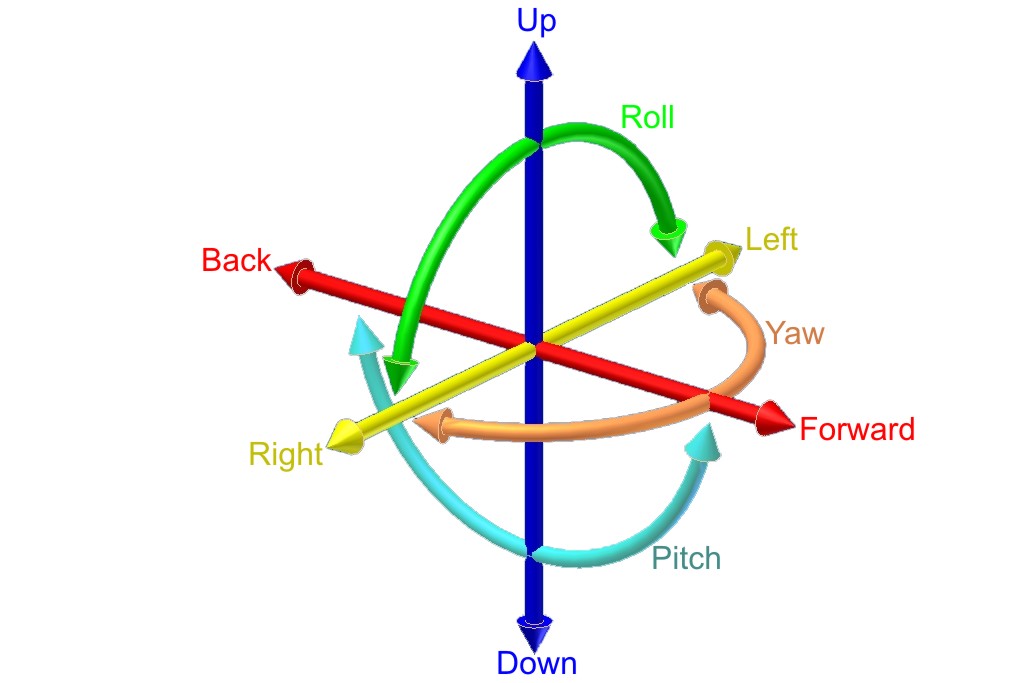

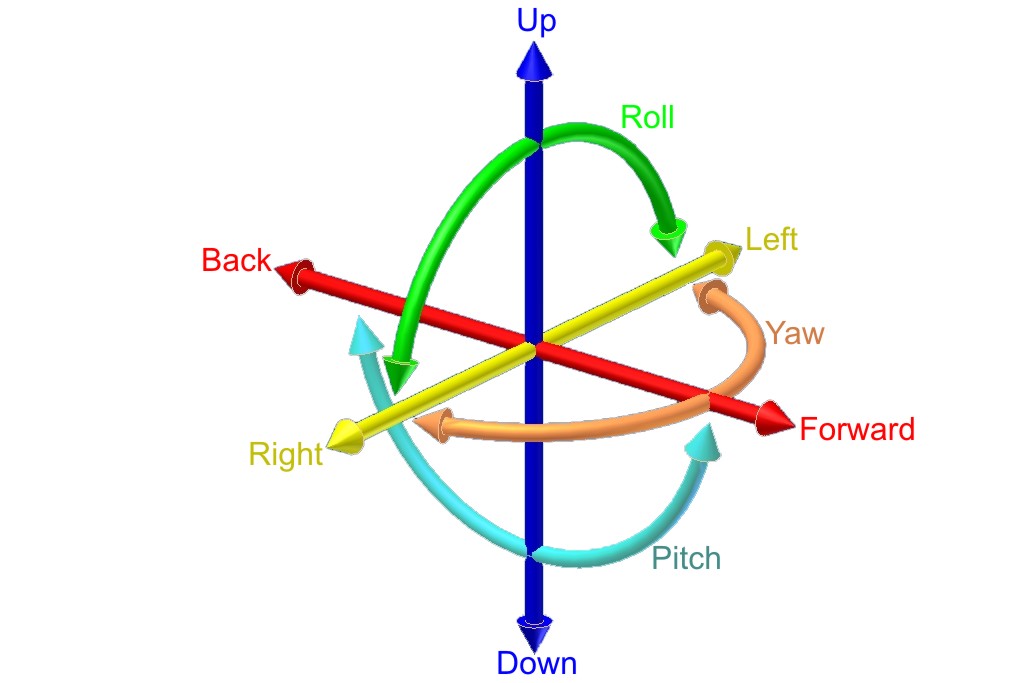

Well developed fins are used for maintaining balance, braking and changing direction. The pectoral fins act as pivots around which the fish can turn rapidly and steer itself. The paired pectoral and pelvic fins control pitching, while the unpaired dorsal and anal fins reduce yawing and rolling. The caudal fin provides raw power for propelling the fish forward.

Body/caudal fin propulsion

There are five groups that differ in the fraction of their body that is displaced laterally:Anguilliform

In the anguilliform group, containing some long, slender fish such as eels, there is little increase in the amplitude of the flexion wave as it passes along the body.

In the anguilliform group, containing some long, slender fish such as eels, there is little increase in the amplitude of the flexion wave as it passes along the body.

Subcarangiform

The subcarangiform group has a more marked increase in wave amplitude along the body with the vast majority of the work being done by the rear half of the fish. In general, the fish body is stiffer, making for higher speed but reduced maneuverability. Trout use sub-carangiform locomotion.Carangiform

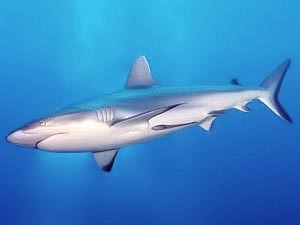

The carangiform group, named for the Carangidae, are stiffer and faster-moving than the previous groups. The vast majority of movement is concentrated in the very rear of the body and tail. Carangiform swimmers generally have rapidly oscillating tails.Thunniform

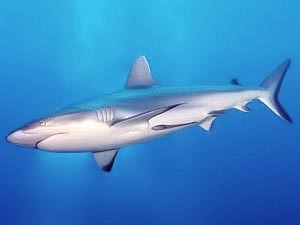

The thunniform group contains high-speed long-distance swimmers, and is characteristic of tunas and is also found in several lamnid sharks. Here, virtually all the sideways movement is in the tail and the region connecting the main body to the tail (the peduncle). The tail itself tends to be large and crescent shaped. This form of swimming enables these fish to chase and catch prey more easily due to the increase in speed of swimming, as in the case of barracudas.

The thunniform group contains high-speed long-distance swimmers, and is characteristic of tunas and is also found in several lamnid sharks. Here, virtually all the sideways movement is in the tail and the region connecting the main body to the tail (the peduncle). The tail itself tends to be large and crescent shaped. This form of swimming enables these fish to chase and catch prey more easily due to the increase in speed of swimming, as in the case of barracudas.

Ostraciiform

The ostraciiform group have no appreciable body wave when they employ caudal locomotion. Only the tail fin itself oscillates (often very rapidly) to create thrust. This group includes Ostraciidae.Median/paired fin propulsion

Not all fish fit comfortably in the above groups. Ocean sunfish, for example, have a completely different system, the tetraodontiform mode, and many small fish use their pectoral fins for swimming as well as for steering and dynamic lift. Fish in the order

Not all fish fit comfortably in the above groups. Ocean sunfish, for example, have a completely different system, the tetraodontiform mode, and many small fish use their pectoral fins for swimming as well as for steering and dynamic lift. Fish in the order Gymnotiformes

The Gymnotiformes are an order of teleost bony fishes commonly known as Neotropical knifefish or South American knifefish. They have long bodies and swim using undulations of their elongated anal fin. Found almost exclusively in fresh water (the ...

possess electric organs along the length of their bodies and swim by undulating an elongated anal fin while keeping the body still, presumably so as not to disturb the electric field that they generate.

Many fish swim using combined behavior of their two pectoral fins or both their anal and dorsal fins. Different types of Median paired fin propulsion can be achieved by preferentially using one fin pair over the other, and include rajiform, diodontiform, amiiform, gymnotiform and balistiform modes.

Rajiform

Rajiform locomotion is characteristic of rays and skates, when thrust is produced by vertical undulations along large, well developed pectoral fins.Diodontiform

Diodontiform locomotion propels the fish propagating undulations along large pectoral fins, as seen in the porcupinefish ( Diodontidae).

Diodontiform locomotion propels the fish propagating undulations along large pectoral fins, as seen in the porcupinefish ( Diodontidae).

Amiiform

Amiiform locomotion consists of undulations of a long dorsal fin while the body axis is held straight and stable, as seen in thebowfin

The bowfin (''Amia calva'') is a bony fish, native to North America. Common names include mudfish, mud pike, dogfish, grindle, grinnel, swamp trout, and choupique. It is regarded as a relict, being the sole surviving species of the Halecomorphi ...

.

Gymnotiform

Gymnotiform locomotion consists of undulations of a long anal fin, essentially upside down amiiform, seen in the South American knifefish ''

Gymnotiform locomotion consists of undulations of a long anal fin, essentially upside down amiiform, seen in the South American knifefish ''Gymnotiformes

The Gymnotiformes are an order of teleost bony fishes commonly known as Neotropical knifefish or South American knifefish. They have long bodies and swim using undulations of their elongated anal fin. Found almost exclusively in fresh water (the ...

''.

Balistiform

In balistiform locomotion, both anal and dorsal fins undulate. It is characteristic of the family Balistidae (triggerfishes). It may also be seen in the Zeidae.Oscillatory

Oscillation is viewed as pectoral-fin-based swimming and is best known as mobuliform locomotion. The motion can be described as the production of less than half a wave on the fin, similar to a bird wing flapping. Pelagic stingrays, such as the manta, cownose, eagle and bat rays use oscillatory locomotion.=Tetraodontiform

= In tetraodontiform locomotion, the dorsal and anal fins are flapped as a unit, either in phase or exactly opposing one another, as seen in the Tetraodontiformes ( boxfishes andpufferfish

Tetraodontidae is a family of primarily marine and estuarine fish of the order Tetraodontiformes. The family includes many familiar species variously called pufferfish, puffers, balloonfish, blowfish, blowies, bubblefish, globefish, swellfis ...

es). The ocean sunfish displays an extreme example of this mode.

=Labriform

= In labriform locomotion, seen in the wrasses ( Labriformes), oscillatory movements of pectoral fins are either drag based or lift based. Propulsion is generated either as a reaction to drag produced by dragging the fins through the water in a rowing motion, or via lift mechanisms.Dynamic lift

Bone and muscle tissues of fish are denser than water. To maintain depth, bony fish increase buoyancy by means of a

Bone and muscle tissues of fish are denser than water. To maintain depth, bony fish increase buoyancy by means of a gas bladder

The swim bladder, gas bladder, fish maw, or air bladder is an internal gas-filled organ that contributes to the ability of many bony fish (but not cartilaginous fish) to control their buoyancy, and thus to stay at their current water depth w ...

. Alternatively, some fish store oils or lipids for this same purpose. Fish without these features use dynamic lift instead. It is done using their pectoral fins in a manner similar to the use of wings by airplanes and birds. As these fish swim, their pectoral fins are positioned to create lift which allows the fish to maintain a certain depth. The two major drawbacks of this method are that these fish must stay moving to stay afloat and that they are incapable of swimming backwards or hovering.

Hydrodynamics

Similarly to the aerodynamics of flight, powered swimming requires animals to overcome drag by producing thrust. Unlike flying, however, swimming animals often do not need to supply much vertical force because the effect of buoyancy can counter the downward pull of gravity, allowing these animals to float without much effort. While there is great diversity in fish locomotion, swimming behavior can be classified into two distinct "modes" based on the body structures involved in thrust production, Median-Paired Fin (MPF) and Body-Caudal Fin (BCF). Within each of these classifications, there are numerous specifications along a spectrum of behaviours from purely undulatory to entirely oscillatory. In undulatory swimming modes, thrust is produced by wave-like movements of the propulsive structure (usually a fin or the whole body). Oscillatory modes, on the other hand, are characterized by thrust produced by swiveling of the propulsive structure on an attachment point without any wave-like motion.Body-caudal fin

Most fish swim by generating undulatory waves that propagate down the body through the caudal fin. This form of undulatory locomotion is termed body-caudal fin (BCF) swimming on the basis of the body structures used; it includes anguilliform, sub-carangiform, carangiform, and thunniform locomotory modes, as well as the oscillatory ostraciiform mode.Adaptation

Similar to adaptation in avian flight, swimming behaviors in fish can be thought of as a balance of stability and maneuverability. Because BCF swimming relies on morecaudal

Caudal may refer to:

Anatomy

* Caudal (anatomical term) (from Latin ''cauda''; tail), used to describe how close something is to the trailing end of an organism

* Caudal artery, the portion of the dorsal aorta of a vertebrate that passes into the ...

body structures that can direct powerful thrust only rearwards, this form of locomotion is particularly effective for accelerating quickly and cruising continuously. BCF swimming is, therefore, inherently stable and is often seen in fish with large migration patterns that must maximize efficiency over long periods. Propulsive forces in MPF swimming, on the other hand, are generated by multiple fins located on either side of the body that can be coordinated to execute elaborate turns. As a result, MPF swimming is well adapted for high maneuverability and is often seen in smaller fish that require elaborate escape patterns.

The habitats occupied by fishes are often related to their swimming capabilities. On coral reefs, the faster-swimming fish species typically live in wave-swept habitats subject to fast water flow speeds, while the slower fishes live in sheltered habitats with low levels of water movement.

Fish do not rely exclusively on one locomotor mode, but are rather locomotor generalists, choosing among and combining behaviors from many available behavioral techniques. Predominantly BCF swimmers often incorporate movement of their pectoral, anal, and dorsal fins as an additional stabilizing mechanism at slower speeds, but hold them close to their body at high speeds to improve streamlining and reducing drag. Zebrafish have even been observed to alter their locomotor behavior in response to changing hydrodynamic influences throughout growth and maturation.

In addition to adapting locomotor behavior, controlling buoyancy effects is critical for aquatic survival since aquatic ecosystems vary greatly by depth. Fish generally control their depth by regulating the amount of gas in specialized organs that are much like balloons. By changing the amount of gas in these swim bladder

The swim bladder, gas bladder, fish maw, or air bladder is an internal gas-filled Organ (anatomy), organ that contributes to the ability of many bony fish (but not cartilaginous fish) to control their buoyancy, and thus to stay at their curren ...

s, fish actively control their density. If they increase the amount of air in their swim bladder, their overall density will become less than the surrounding water, and increased upward buoyancy pressures will cause the fish to rise until they reach a depth at which they are again at equilibrium with the surrounding water.

Flight

The transition of predominantly swimming locomotion directly to flight has evolved in a single family of marine fish, the Exocoetidae. Flying fish are not true fliers in the sense that they do not execute powered flight. Instead, these species glide directly over the surface of the ocean water without ever flapping their "wings." Flying fish have evolved abnormally large pectoral fins that act as airfoils and provide lift when the fish launches itself out of the water. Additional forward thrust and steering forces are created by dipping the hypocaudal (i.e. bottom) lobe of their caudal fin into the water and vibrating it very quickly, in contrast to diving birds in which these forces are produced by the same locomotor module used for propulsion. Of the 64 extant species of flying fish, only two distinct body plans exist, each of which optimizes two different behaviors.Fish, F.E. (1990) Wing design and scaling of flying fish with regard to flight performance. "J. Zool. Lond." 221, 391-403.Fish, Frank. (1991) On a Fin and a Prayer. "Scholars." 3(1), 4-7.

Tradeoffs

While most fish have caudal fins with evenly sized lobes (i.e. homocaudal), flying fish have an enlarged ventral lobe (i.e. hypocaudal) which facilitates dipping only a portion of the tail back onto the water for additional thrust production and steering. Because flying fish are primarily aquatic animals, their body density must be close to that of water for buoyancy stability. This primary requirement for swimming, however, means that flying fish are heavier (have a larger mass) than other habitual fliers, resulting in higher wing loading and lift to drag ratios for flying fish compared to a comparably sized bird. Differences in wing area, wing span, wing loading, and aspect ratio have been used to classify flying fish into two distinct classifications based on these different aerodynamic designs.Biplane body plan

In thebiplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While ...

or '' Cypselurus'' body plan, both the pectoral and pelvic fins are enlarged to provide lift during flight. These fish also tend to have "flatter" bodies which increase the total lift-producing area, thus allowing them to "hang" in the air better than more streamlined shapes. As a result of this high lift production, these fish are excellent gliders and are well adapted for maximizing flight distance and duration.

Comparatively, '' Cypselurus'' flying fish have lower wing loading and smaller aspect ratios (i.e. broader wings) than their '' Exocoetus'' monoplane counterparts, which contributes to their ability to fly for longer distances than fish with this alternative body plan. Flying fish with the biplane design take advantage of their high lift production abilities when launching from the water by utilizing a "taxiing glide" in which the hypocaudal lobe remains in the water to generate thrust even after the trunk clears the water's surface and the wings are opened with a small angle of attack for lift generation.

Monoplane body plan

In the '' Exocoetus'' or monoplane body plan, only the pectoral fins are enlarged to provide lift. Fish with this body plan tend to have a more streamlined body, higher aspect ratios (long, narrow wings), and higher wing loading than fish with the biplane body plan, making these fish well adapted for higher flying speeds. Flying fish with a monoplane body plan demonstrate different launching behaviors from their biplane counterparts. Instead of extending their duration of thrust production, monoplane fish launch from the water at high speeds at a large angle of attack (sometimes up to 45 degrees). In this way, monoplane fish are taking advantage of their adaptation for high flight speed, while fish with biplane designs exploit their lift production abilities during takeoff.Walking

A "walking fish" is a fish that is able to travel over land for extended periods of time. Some other cases of nonstandard fish locomotion include fish "walking" along thesea floor

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as 'seabeds'.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

, such as the handfish or frogfish.

Most commonly, walking fish are amphibious fish

Amphibious fish are fish that are able to leave water for extended periods of time. About 11 distantly related genera of fish are considered amphibious. This suggests that many fish genera independently evolved amphibious traits, a process known ...

. Able to spend longer times out of water, these fish may use a number of means of locomotion, including springing, snake-like lateral undulation, and tripod-like walking. The mudskipper

Mudskippers are any of the 23 extant species of amphibious fish from the subfamily Oxudercinae of the goby family Oxudercidae. They are known for their unusual body shapes, preferences for semiaquatic habitats, limited terrestrial locomotion and ...

s are probably the best land-adapted of contemporary fish and are able to spend days moving about out of water and can even climb mangroves, although to only modest heights. The Climbing gourami is often specifically referred to as a "walking fish", although it does not actually "walk", but rather moves in a jerky way by supporting itself on the extended edges of its gill plates and pushing itself by its fins and tail. Some reports indicate that it can also climb trees.

There are a number of fish that are less adept at actual walking, such as the walking catfish. Despite being known for "walking on land", this fish usually wriggles and may use its pectoral fins to aid in its movement. Walking Catfish have a respiratory system that allows them to live out of water for several days. Some are invasive species

An invasive species otherwise known as an alien is an introduced organism that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment. Although most introduced species are neutral or beneficial with respect to other species, invasive species ad ...

. A notorious case in the United States is the Northern snakehead. Polypterids have rudimentary lungs and can also move about on land, though rather clumsily. The Mangrove rivulus can survive for months out of water and can move to places like hollow logs.

There are some species of fish that can "walk" along the sea floor but not on land; one such animal is the

There are some species of fish that can "walk" along the sea floor but not on land; one such animal is the flying gurnard

The flying gurnard (''Dactylopterus volitans''), also known as the helmet gurnard, is a bottom-dwelling fish of tropical to warm temperate waters on both sides of the Atlantic. On the American side, it is found as far north as Massachusetts (ex ...

(it does not actually fly, and should not be confused with flying fish). The batfishes of the family Ogcocephalidae (not to be confused with batfish of Ephippidae

Ephippidae is a family containing the spadefishes, with about eight genera and a total of 20 marine species. Well-known species include the Atlantic spadefish (''Chaetodipterus faber'') and the reef-dwelling genus ''Platax'', the batfishes, whic ...

) are also capable of walking along the sea floor. '' Bathypterois grallator'', also known as a "tripodfish", stands on its three fins on the bottom of the ocean and hunts for food. The African lungfish (''P. annectens'') can use its fins to ''"walk"'' along the bottom of its tank in a manner similar to the way amphibians and land vertebrates use their limbs on land.

Burrowing

Many fishes, particularly eel-shaped fishes such as true eels, moray eels, and spiny eels, are capable ofburrow

An Eastern chipmunk at the entrance of its burrow

A burrow is a hole or tunnel excavated into the ground by an animal to construct a space suitable for habitation or temporary refuge, or as a byproduct of locomotion. Burrows provide a form of sh ...

ing through sand or mud. Ophichthids, the snake eels, are capable of burrowing either forwards or backwards.

Larval fish

Locomotion

Swimming

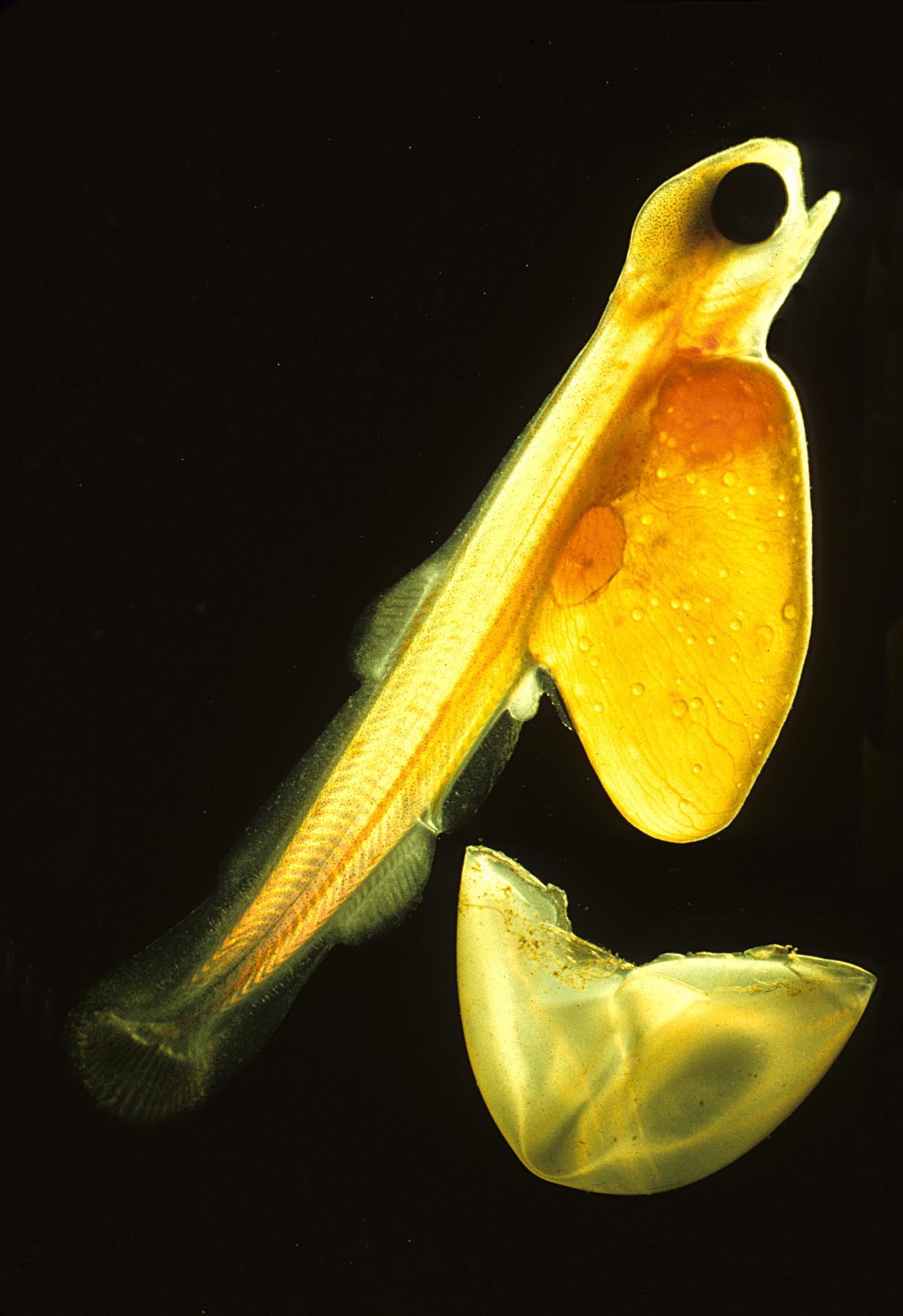

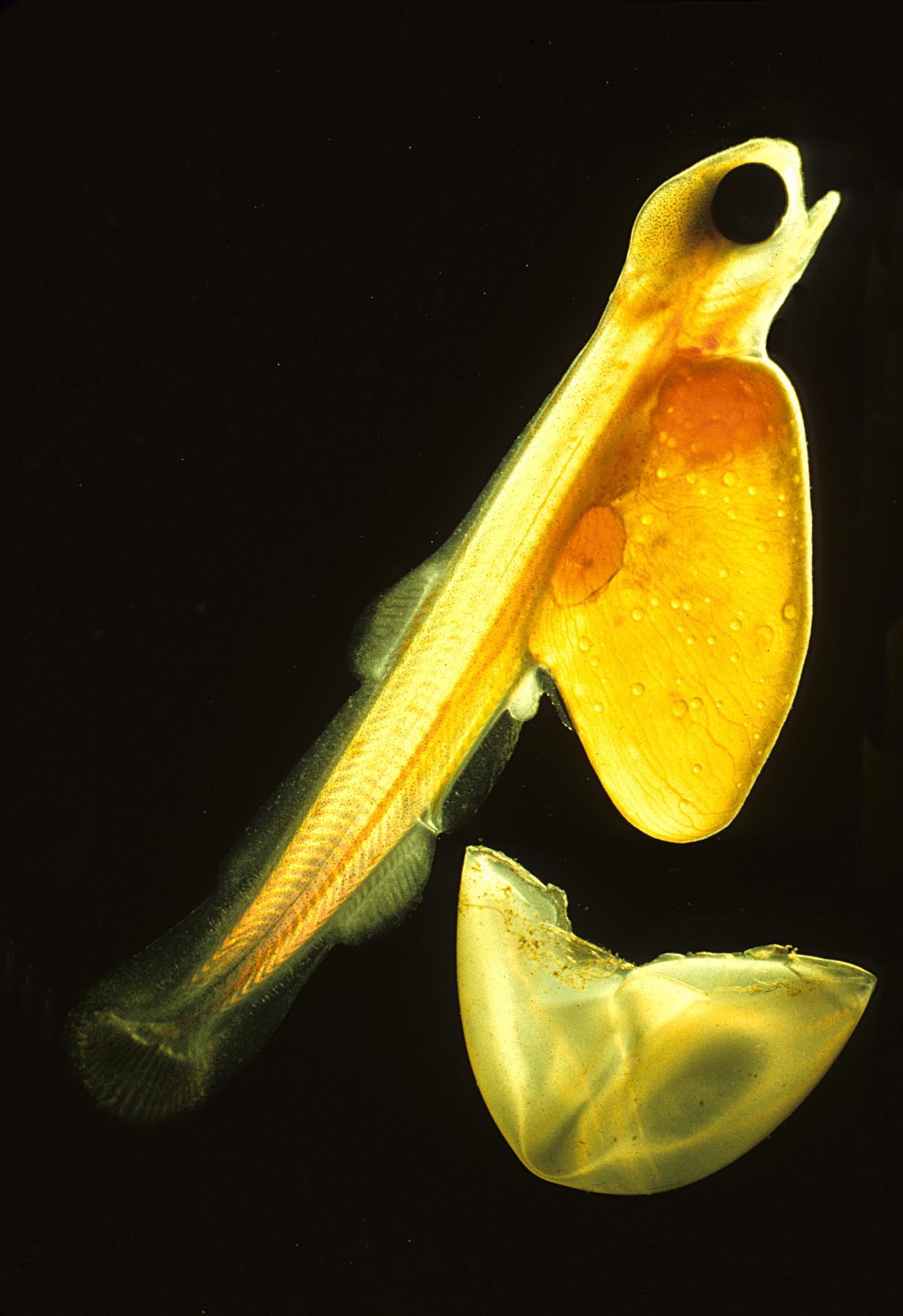

Fish larvae, like many adult fishes, swim by undulating their body. The swimming speed varies proportionally with the size of the animals, in that smaller animals tend to swim at lower speeds than larger animals. The swimming mechanism is controlled by the flow regime of the larvae.

Fish larvae, like many adult fishes, swim by undulating their body. The swimming speed varies proportionally with the size of the animals, in that smaller animals tend to swim at lower speeds than larger animals. The swimming mechanism is controlled by the flow regime of the larvae. Reynolds number

In fluid mechanics, the Reynolds number () is a dimensionless quantity that helps predict fluid flow patterns in different situations by measuring the ratio between inertial and viscous forces. At low Reynolds numbers, flows tend to be domi ...

(Re) is defined as the ratio of inertial force to viscous force. Smaller organisms are affected more by viscous forces, like friction, and swim at a smaller Reynolds number. Larger organisms use a larger proportion of inertial forces, like pressure, to swim, at a higher Reynolds number.‘Flow Patterns Of Larval Fish: Undulatory Swimming in the Intermediate Flow Regime’ by Ulrike K. Müller, Jos G. M. van den Boogaart and Johan L. van Leeuwen. Journal of Experimental Biology 2008 211: 196-205; doi: 10.1242/jeb.005629

The larvae of ray finned fishes, the Actinopterygii

Actinopterygii (; ), members of which are known as ray-finned fishes, is a class of bony fish. They comprise over 50% of living vertebrate species.

The ray-finned fishes are so called because their fins are webs of skin supported by bony or h ...

, swim at a quite large range of Reynolds number (Re ≈10 to 900). This puts them in an intermediate flow regime where both inertial and viscous forces play an important role. As the size of the larvae increases, the use of pressure forces to swim at higher Reynolds number increases.

Undulatory swimmers generally shed at least two types of wake: Carangiform swimmers shed connected vortex loops and Anguilliform swimmers shed individual vortex rings. These vortex rings depend upon the shape and arrangement of the trailing edge from which the vortices are shed. These patterns depend upon the swimming speed, ratio of swimming speed to body wave speed and the shape of body wave.

A spontaneous bout of swimming has three phases. The first phase is the start or acceleration phase: In this phase the larva tends to rotate its body to make a 'C' shape which is termed the preparatory stroke. It then pushes in the opposite direction to straighten its body, which is called a propulsive stroke, or a power stroke, which powers the larva to move forward. The second phase is cyclic swimming. In this phase, the larva swims with an approximately constant speed. The last phase is deceleration. In this phase, the swimming speed of the larva gradually slows down to a complete stop. In the preparatory stroke, due to the bending of the body, the larva creates 4 vortices around its body, and 2 of those are shed in the propulsive stroke. Similar phenomena can be seen in the deceleration phase. However, in the vortices of the deceleration phase, a large area of elevated vorticity can be seen compared to the starting phase.

The swimming abilities of larval fishes are important for survival. This is particularly true for the larval fishes with higher metabolic rate and smaller size which makes them more susceptible to predators. The swimming ability of a reef fish larva helps it to settle at a suitable reef and for locating its home as it is often isolated from its home reef in search of food. Hence the swimming speed of reef fish larvae are quite high (≈12 cm/s - 100 cm/s) compared to other larvae."Critical Swimming Speeds of Late-Stage Coral Reef Fish Larvae: Variation within Species, Among Species and Between Locations" by Fisher, R., Leis, J.M., Clark, D.L.in Marine Biology (2005) 147: 1201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-005-0001-x, The swimming speeds of larvae from the same families at the two locations are relatively similar. However, the variation among individuals is quite large. At the species level, length is significantly related to swimming ability. However, at the family level, only 16% of variation in swimming ability can be explained by length. There is also a negative correlation between the fineness ratio and the swimming ability of reef fish larvae. This suggests a minimization of overall drag and maximization of volume. Reef fish larvae differ significantly in their critical swimming speed abilities among taxa which leads to high variability in sustainable swimming speed. This again leads to sustainable variability in their ability to alter dispersal patterns, overall dispersal distances and control their temporal and spatial patterns of settlement.

Hydrodynamics

Small undulatory swimmers experience both inertial and viscous forces, the relative importance of which is indicated by Reynolds number (Re). Reynolds number is proportional to body size and swimming speed. The swimming performance of a larva increases between 2–5 days post fertilization (d.p.f.). Compared with adults, the larval fish experience relatively high viscous force. To enhance thrust to an equal level with the adults, it increases its tail beat frequency and thus amplitude. Tail beat frequency increases over larval age to 95 Hz in 3 days post fertilization (d.p.f.) from 80 Hz in 2 days post fertilization (d.p.f.). This higher frequency leads to higher swimming speed, thus reducing predation and increasing prey catching ability when they start feeding at around 5 days post fertilization (d.p.f.). The vortex shedding mechanics changes with the flow regime in an inverse non-linear way. Strouhal number (St) is considered as a design parameter for vortex shedding mechanism and can be defined as a ratio of product of tail beat frequency with amplitude with the mean swimming speed. Reynolds number (Re) is the main deciding criteria of a flow regime. It has been observed over different type of larval experiments that, slow larvae swims at higher Strouhal number but lower Reynolds number. However, the faster larvae swims distinctively at opposite conditions, that is, at lower Strouhal number but higher Reynolds number. Strouhal number is constant over similar speed ranged adult fishes. Strouhal number does not only depend on the small size of the swimmers, but also dependent to the flow regime. As in fishes which swim in viscous or high-friction flow regime, would create high body drag which will lead to higher Strouhal number. Whereas, in high viscous regime, the adults swim at lower stride length which leads to lower tail beat frequency and lower amplitude. This leads to higher thrust for same displacement or higher propulsive force, which unanimously reduces the Reynolds number. Larval fishes start feeding at 5–7 days post fertilization (d.p.f.). And they experience extreme mortality rate (≈99%) in the few days after feeding starts. The reason for this 'Critical Period' (Hjort-1914) is mainly hydrodynamic constraints. Larval fish fail to eat even if there are enough prey encounters. One of the primary determinants of feeding success is the size of larval body. The smaller larvae function in a lower Reynolds number (Re) regime. As the age increases, the size of the larvae increases, which leads to higher swimming speed and increased Reynolds number. It has been observed through many experiments that the Reynolds number of successful strikes (Re~200) is much higher than the Reynolds number of failed strikes (Re~20),.'Hydrodynamic Regime Determines The Feeding Success Of Larval Fish Through The Modulation Of Strike Kinematics' by Victor China, Liraz Levy, Alex Liberzon, Tal Elmaliach, Roi Holzman in Proc. R. Soc. B 2017 284 20170235; DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2017.0235. Published 26 April 2017 Numerical analysis of suction feeding at a low Reynolds number (Re) concluded that around 40% energy invested in mouth opening is lost to frictional forces rather than contributing to accelerating the fluid towards mouth. Ontogenetic improvement in the sensory system, coordination and experiences are non-significant relationship while determining feeding success of larvae A successful strike positively depends upon the peak flow speed or the speed of larvae at the time of strike. The peak flow speed is also dependent on the gape speed or the speed of opening the buccal cavity to capture food. As the larva ages, its body size increase and its gape speed also increase, which cumulatively increase the successful strike outcomes. Hence larger larvae can capture faster escaping prey and exert sufficient force to suck heavier prey into their mouths. The ability of a larval prey to survive an encounter with predator totally depends on its ability to sense and evade the strike. Adult fishes exhibit rapid suction feeding strikes as compared to larval fishes. Sensitivity of larval fish to velocity and flow fields provides the larvae a critical defense against predation. Though many prey use their visual system to detect and evade predators when there is light, it is hard for the prey to detect predators at night, which leads to a delayed response to the attack. There is a mechano-sensory system in fishes to identify the different flow generated by different motion surrounding the water and between the bodies called as lateral line system.'Zebrafish Larvae Evade Predators By Sensing Water Flow' by William J. Stewart, Gilberto S. Cardenas, Matthew J. McHenry in Journal of Experimental Biology 2013 216: 388-398; doi: 10.1242/jeb.072751 After detecting a predator, a larva evades its strike by 'fast start' or 'C' response. There are other aquatic prey which use similar systems, such as copepods which sense water flow with their setae located along their antennas; crustaceans use their mechano-sensation as both prey and predator. A swimming fish disturbs a volume of water ahead of its body with a flow velocity that increases with the proximity to the body. This particular phenomena can sometimes be called a 'Bow Wave'.'Quantification Of Flow During Suction Feeding Of Bluegill Sunfish' by Ferry, Lara & Wainwright, Peter & Lauder, George in Zoology (Jena, Germany). 106. 159-68. 10.1078/0944-2006-00110 The timing of the 'C' start response affects escape probability inversely. Escape probability increases with the distance from the predator at the time of strike. In general, prey successfully evade a predator strike from an intermediate distance (3–6 mm) from the predator. The prey could react even before the suction feeding by detecting the flow generation of an approaching predator by startle response. Well timed escape maneuvers can be crucial for the survival of larval fish.Atlantic herring

Atlantic herring (''Clupea harengus'') is a herring in the family (biology), family Clupeidae. It is one of the most abundant fish species in the world. Atlantic herrings can be found on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, congregating in large ...

eggs, with a newly hatched larva

File:Clupealarvamatchkils.jpg, Freshly hatched herring larva in a drop of water compared to a match head.

File:Lanternfish larva.jpg, Late stage lanternfish larva

File:Arnoglossus laterna larva.jpg, A 9mm long late stage scaldfish larva

File:LeptocephalusConger.jpg, Larva of a conger eel, 7.6 cm

File:Larval stage of bluefin tuna.jpg, Bluefin tuna larva

File:Pacific cod larvae.jpg, Pacific cod larva

File:Walleye larva (8740460659).jpg, Walleye larva

File:Common sturgeon larva.jpg, Common sturgeon

The European sea sturgeon (''Acipenser sturio''), also known as the Atlantic sturgeon or common sturgeon, is a species of sturgeon native to Europe. It was formerly abundant, being found in coastal habitats all over Europe. It is anadromous and b ...

larva

File:FMIB 47039 Ostracion hoops.jpeg, Boxfish larva

File:Molalavdj.jpg, Ocean sunfish larva, 2.7mm

Behavior

Objective quantification is complicated in higher vertebrates by the complex and diverse locomotor repertoire and neural system. However, the relative simplicity of a juvenile brain and simple nervous system of fishes with fundamental neuronal pathways allows zebrafish larvae to be an apt model to study the interconnection between locomotor repertoire and neuronal system of a vertebrate. Behavior represents the unique interface between intrinsic and extrinsic forces that determine an organism's health and survival.‘Locomotion In Larval Zebrafish: Influence of Time of Day, Lighting and Ethanol’ by R.C. MacPhail, J. Brooks, D.L. Hunter, B. Padnos a, T.D. Irons, S. Padilla in Neurotoxicology. 30. 52-8. 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.09.011. Larval zebrafish perform many locomotor behavior such as escape response, prey tracking, optomotor response etc. These behaviors can be categorized with respect to body position as ‘C’-starts, ‘J’-turns, slow scoots, routine turns etc. Fish larvae respond to abrupt changes in illumination with distinct locomotor behavior. The larvae show high locomotor activity during periods of bright light compared to dark. This behavior can direct towards the idea of searching food in light whereas the larvae do not feed in dark.‘Modulation of Locomotor Activity in Larval Zebrafish During Light Adaptation’ by Harold A. Burgess and Michael Granato. In Journal of Experimental Biology 2007 210: 2526-2539; doi: 10.1242/jeb.003939 Also light exposure directly manipulates the locomotor activities of larvae throughout circadian period of light and dark with higher locomotor activity in light condition than in dark condition which is very similar as seen in mammals. Following the onset of darkness, larvae shows hyperactive scoot motion prior to a gradual drop off. This behavior could possibly be linked to find a shelter before nightfall. Also larvae can treat this sudden nightfall as under debris and the hyperactivity can be explained as the larvae navigation back to illuminated areas. Prolonged dark period can reduce the light-dark responsiveness of larvae. Following light extinction, larvae execute large angle turns towards the vanished light source, which explains the navigational response of a larva. Acute ethanol exposure reduce visual sensitivity of larvae causing a latency to respond in light and dark period change.See also

* * Microswimmer * * *References

Further reading

* Alexander, R. McNeill (2003) ''Principles of Animal Locomotion.'' Princeton University Press. . * * * Videler JJ (1993''Fish Swimming''

Springer. . * Vogel, Steven (1994) ''Life in Moving Fluid: The Physical Biology of Flow.'' Princeton University Press. (particularly pp. 115–117 and pp. 207–216 for specific biological examples swimming and flying respectively) * Wu, Theodore, Y.-T., Brokaw, Charles J., Brennen, Christopher, Eds. (1975) ''Swimming and Flying in Nature''. Volume 2, Plenum Press. (particularly pp. 615–652 for an in depth look at fish swimming)

External links

How fish swim: study solves muscle mystery

Simulated fish locomotion

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20110724192433/http://www.geol.umd.edu/~jmerck/bsci392/lecture10/lecture10.html The biomechanics of swimming {{fins, limbs and wings Ichthyology Aquatic locomotion Animal locomotion Articles containing video clips