Radcliffe Line on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Radcliffe Line was the boundary demarcated by the two boundary commissions for the provinces of

After the breakdown of the 1945 Simla Conference of viceroy Lord Wavell, the idea of Pakistan began to be contemplated seriously. Sir Evan Jenkins, the private secretary of the viceroy (later the governor of Punjab), wrote a memorandum titled "Pakistan and the Punjab", where he discussed the issues surrounding the partition of Punjab. K. M. Panikkar, then prime minister of the

After the breakdown of the 1945 Simla Conference of viceroy Lord Wavell, the idea of Pakistan began to be contemplated seriously. Sir Evan Jenkins, the private secretary of the viceroy (later the governor of Punjab), wrote a memorandum titled "Pakistan and the Punjab", where he discussed the issues surrounding the partition of Punjab. K. M. Panikkar, then prime minister of the

In March 1946, the British government sent a Cabinet Mission to India to find a solution to resolve the conflicting demands of Congress and the Muslim League. Congress agreed to allow Pakistan to be formed with 'genuine Muslim areas'. The Sikh leaders asked for a Sikh state with

In March 1946, the British government sent a Cabinet Mission to India to find a solution to resolve the conflicting demands of Congress and the Muslim League. Congress agreed to allow Pakistan to be formed with 'genuine Muslim areas'. The Sikh leaders asked for a Sikh state with

Routing borders between territories, discourses, and practices (p. 128)

* Chester, Lucy P

''Borders and Conflict in South Asia: The Radcliffe Boundary Commission and the Partition of Punjab''.

Manchester UP, 2009. * Collins, L., and Lapierre, D. (1975) '' Freedom at Midnight''. * Collins, L., and Lapierre, D

''Mountbatten and the Partition of India''

Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, 1983. * Heward, E. ''The Great and the Good: A Life of Lord Radcliffe''. Chichester: Barry Rose Publishers, 1994. * * Moon, P

The Transfer of Power, 1942–7: Constitutional Relations Between Britain and India: Volume X: The Mountbatten Viceroyalty – Formulation of a Plan

22 March–30 May 1947

Review "Dividing the Jewel" at JSTOR

* Moon, Blake, D., and Ashton, S

The Transfer of Power, 1942–7: Constitutional Relations Between Britain and India: Volume XI: The Mountbatten Viceroyalty Announcement and Reception of the 3rd June Plan 31 May–7 July 1947

Review "Dividing the Jewel" at JSTOR

* Smitha, F

MacroHistory website, 2001. * Tunzelmann, A. ''Indian Summer''. Henry Holt. * Wolpert, S. (1989). ''A New History of India'', 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

{{Pakistan Movement Bangladesh–India border Geography of India India–Pakistan border Pakistan Movement Partition of India Eponymous border lines Territorial evolution of Bangladesh

Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

and Bengal

Bengal ( ) is a Historical geography, historical geographical, ethnolinguistic and cultural term referring to a region in the Eastern South Asia, eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. The region of Benga ...

during the Partition of India

The partition of India in 1947 was the division of British India into two independent dominion states, the Dominion of India, Union of India and Dominion of Pakistan. The Union of India is today the Republic of India, and the Dominion of Paki ...

. It is named after Cyril Radcliffe, who, as the joint chairman of the two boundary commissions, had the ultimate responsibility to equitably divide of territory with 88 million people.

The term "Radcliffe Line" is also sometimes used for the entire boundary between India and Pakistan. However, outside of Punjab and Bengal, the boundary is made of existing provincial boundaries and had nothing to do with the Radcliffe commissions.

The demarcation line was published on 17 August 1947, two days after the independence of Pakistan and India. Today, the Punjab part of the line is part of the India–Pakistan border while the Bengal part of the line serves as the Bangladesh–India border

The Bangladesh–India border, known locally as the Radcliffe line, is an international boundary, international border running between the republics of Bangladesh and India. Six Divisions of Bangladesh, Bangladeshi divisions and five States and ...

.

Background

Events leading up to the Radcliffe Boundary Commissions

On 18 July 1947, theIndian Independence Act 1947

The Indian Independence Act 1947 ( 10 & 11 Geo. 6. c. 30) is an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that partitioned British India into the two new independent dominions of India and Pakistan. The Act received Royal Assent on 18 July 194 ...

of the Parliament of the United Kingdom stipulated that British rule in India would come to an end just one month later, on 15 August 1947. The Act also stipulated the partition of the Presidencies and provinces of British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance in South Asia. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one form or another ...

into two new sovereign dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

s: India and Pakistan.

Pakistan was intended as a Muslim homeland, while India remained secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin , or or ), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. The origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself. The concept was fleshed out through Christian hi ...

. Muslim-majority British provinces in the northwest were to become the foundation of Pakistan. The provinces of Baluchistan

Balochistan ( ; , ), also spelled as Baluchistan or Baluchestan, is a historical region in West and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian Sea coastline. This arid region of de ...

(91.8% Muslim before partition) and Sindh

Sindh ( ; ; , ; abbr. SD, historically romanized as Sind (caliphal province), Sind or Scinde) is a Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Pakistan. Located in the Geography of Pakistan, southeastern region of the country, Sindh is t ...

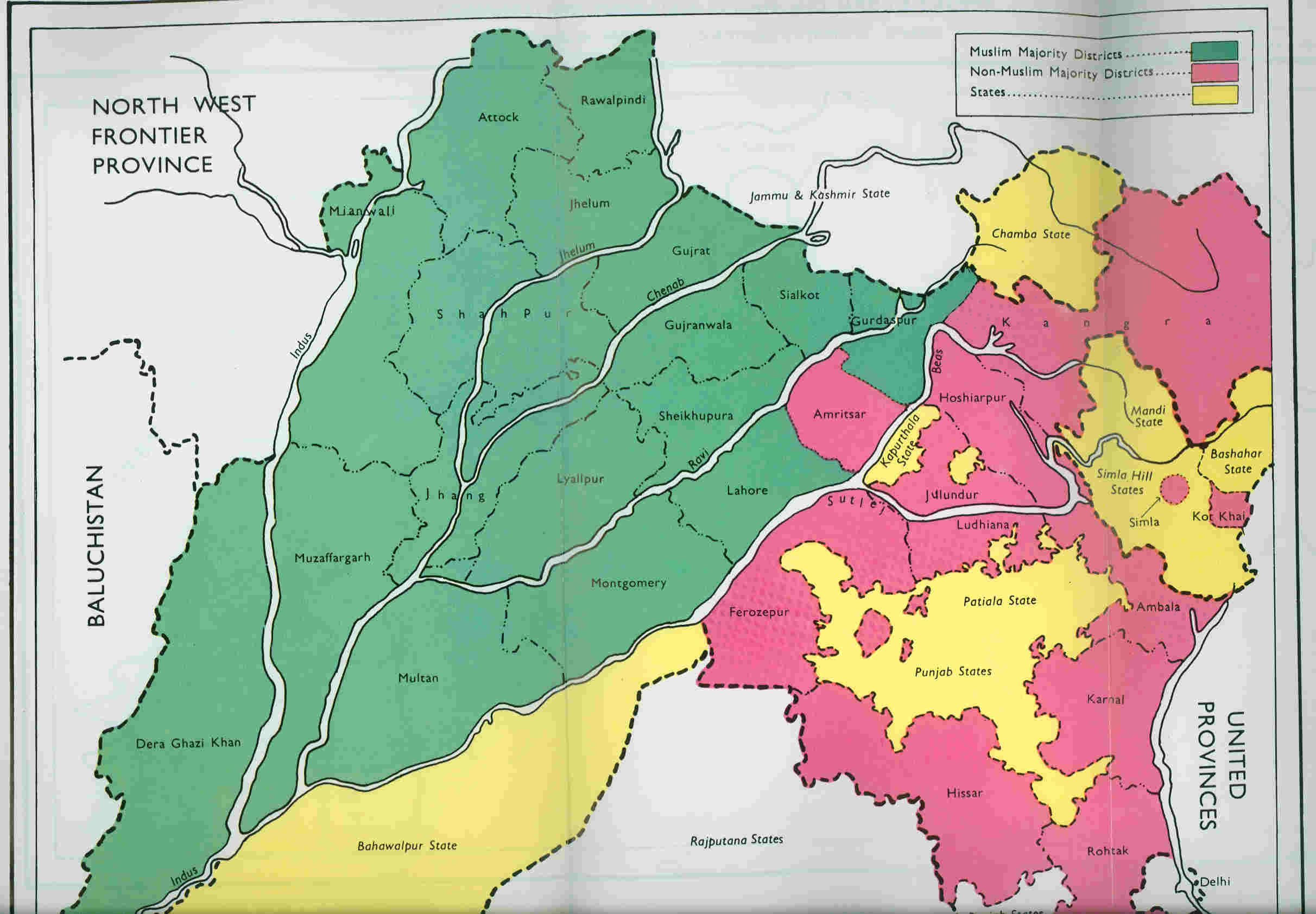

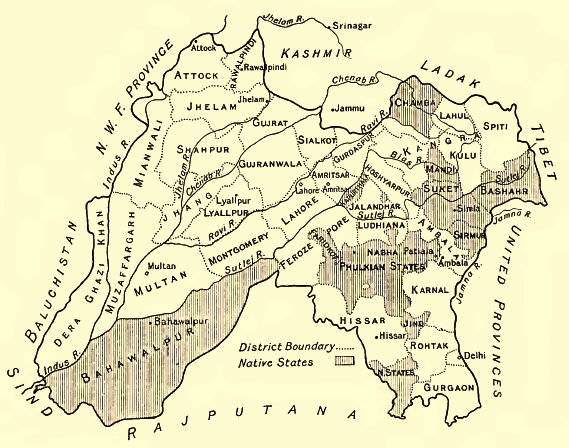

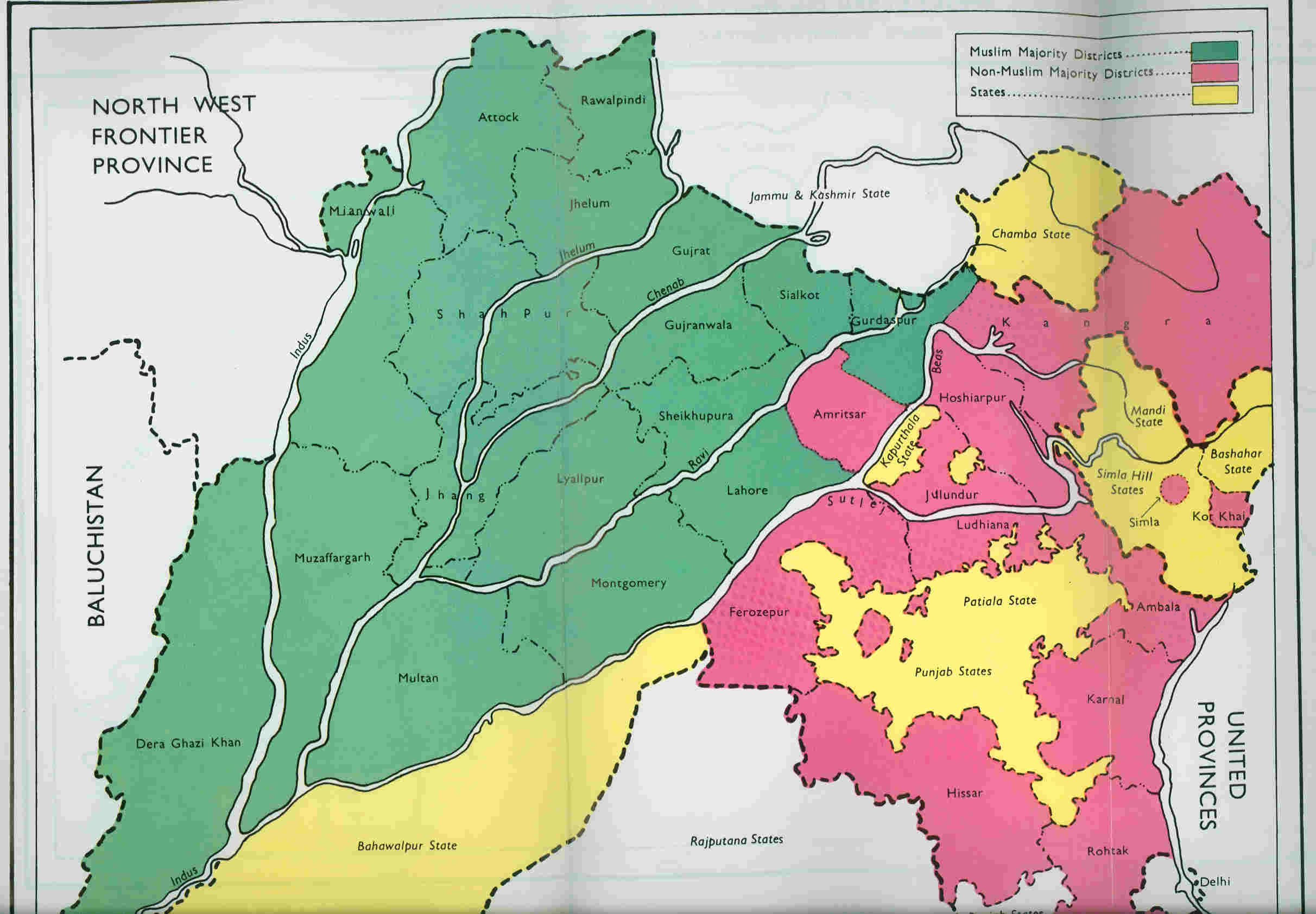

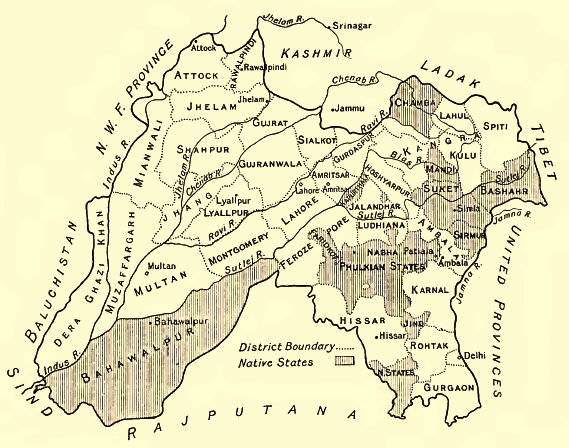

(72.7%) and North-West Frontier Province became entirely Pakistani territory. However, two provinces did not have an overwhelming Muslim majority—Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

in the northwest (55.7% Muslim) and Bengal

Bengal ( ) is a Historical geography, historical geographical, ethnolinguistic and cultural term referring to a region in the Eastern South Asia, eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. The region of Benga ...

in the northeast (54.4% Muslim). After elaborate discussions, these two provinces ended up being partitioned between India and Pakistan.

The Punjab's population distribution was such that there was no line that could neatly divide the Hindus

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

, Muslims

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

, and Sikhs

Sikhs (singular Sikh: or ; , ) are an ethnoreligious group who adhere to Sikhism, a religion that originated in the late 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, based on the revelation of Guru Nanak. The term ''Sikh'' ...

. Likewise, no line could appease both the Muslim League, headed by Jinnah, and the Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

led by Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

and Vallabhbhai Patel

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel (; ''Vallabhbhāī Jhāverbhāī Paṭel''; 31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), commonly known as Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, was an Indian independence activist and statesman who served as the first Deputy Prime ...

. Moreover, any division based on religious communities was sure to entail "cutting through road and rail communications, irrigation schemes, electric power systems and even individual landholdings."

Prior ideas of partition

The idea of partitioning the provinces of Bengal and Punjab had been present since the beginning of the 20th century. Bengal had in fact been partitioned by the then viceroyLord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), known as Lord Curzon (), was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician, explorer and writer who served as Viceroy of India ...

in 1905, along with its adjoining regions. The resulting 'Eastern Bengal and Assam' province, with its capital at Dhaka

Dhaka ( or ; , ), List of renamed places in Bangladesh, formerly known as Dacca, is the capital city, capital and list of cities and towns in Bangladesh, largest city of Bangladesh. It is one of the list of largest cities, largest and list o ...

, had a Muslim majority and the 'West Bengal' province, with its capital at Calcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

, had a Hindu majority. However, this partition of Bengal was reversed in 1911 in an effort to mollify Bengali nationalism

Bengali nationalism (, ) is a form of ethnic nationalism that focuses on Bengalis as a single ethnicity by rejecting imposition of other languages and cultures while promoting its own in Bengal. Bengalis speak the Bengali language and mos ...

.

Proposals for partitioning Punjab had been made starting in 1908. Its proponents included the Hindu leader Bhai Parmanand, Congress leader Lala Lajpat Rai

Lala Lajpat Rai (28 January 1865 — 17 November 1928) was an Indian revolutionary, politician, and author, popularly known as ''Punjab Kesari (Lion of Punjab).'' He was one of the three members of the Lal Bal Pal trio. He died of severe tra ...

, industrialist G. D. Birla, and various Sikh leaders. After the 1940 Lahore resolution

The Lahore Resolution, later called the Pakistan Resolution in Pakistan, was a formal political statement adopted by the All-India Muslim League on the occasion of its three-day general session in Lahore, Punjab, from 22 to 24 March 1940, call ...

of the Muslim League demanding Pakistan, B. R. Ambedkar wrote a 400-page tract titled ''Thoughts on Pakistan.'' In the tract, he discussed the boundaries of Muslim and non-Muslim regions of Punjab and Bengal. His calculations showed a Muslim majority in 16 western districts of Punjab and non-Muslim majority in 13 eastern districts. In Bengal, he showed non-Muslim majority in 15 districts. He thought the Muslims could have no objection to redrawing provincial boundaries. If they did, "they idnot understand the nature of their own demand".

After the breakdown of the 1945 Simla Conference of viceroy Lord Wavell, the idea of Pakistan began to be contemplated seriously. Sir Evan Jenkins, the private secretary of the viceroy (later the governor of Punjab), wrote a memorandum titled "Pakistan and the Punjab", where he discussed the issues surrounding the partition of Punjab. K. M. Panikkar, then prime minister of the

After the breakdown of the 1945 Simla Conference of viceroy Lord Wavell, the idea of Pakistan began to be contemplated seriously. Sir Evan Jenkins, the private secretary of the viceroy (later the governor of Punjab), wrote a memorandum titled "Pakistan and the Punjab", where he discussed the issues surrounding the partition of Punjab. K. M. Panikkar, then prime minister of the Bikaner State

Bikaner State was the princely state, Princely State in the north-western most part of the History of Bikaner, Rajputana province of imperial British India from 1818 to 1947. The founder of the state Rao Bika was a younger son of Rao ...

, sent a memorandum to the viceroy titled "Next Step in India", wherein he recommended that the principle of 'Muslim homeland' be conceded but territorial adjustments made to the two provinces to meet the claims of the Hindus and Sikhs. Based on these discussions, the viceroy sent a note on the "Pakistan theory" to the Secretary of State for India

His (or Her) Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for India, known for short as the India secretary or the Indian secretary, was the British Cabinet minister and the political head of the India Office responsible for the governance of ...

. The viceroy informed the Secretary of State that Jinnah envisaged the ''full provinces'' of Bengal and Punjab going to Pakistan with only minor adjustments, whereas Congress was expecting ''almost half'' of these provinces to remain in India. This essentially framed the problem of partition.

The Secretary of State responded by directing Lord Wavell to send 'actual proposals for defining genuine Muslim areas'. The task fell on V. P. Menon, the Reforms Commissioner, and his colleague Sir B. N. Rau in the Reforms Office. They prepared a note called "Demarcation of Pakistan Areas", where they included the three western divisions of Punjab ( Rawalpindi, Multan and Lahore) in Pakistan, leaving two eastern divisions of Punjab in India ( Jullundur and Delhi). However, they noted that this allocation would leave 2.2 million Sikhs in the Pakistan area and about 1.5 million in India. Excluding the Amritsar

Amritsar, also known as Ambarsar, is the second-List of cities in Punjab, India by population, largest city in the India, Indian state of Punjab, India, Punjab, after Ludhiana. Located in the Majha region, it is a major cultural, transportatio ...

and Gurdaspur

Gurdaspur is a city in the Majha region of the Indian state of Punjab, between the rivers Beas and Ravi. It houses the administrative headquarters of Gurdaspur District and is in the geographical centre of the district, which shares a bord ...

districts of the Lahore Division from Pakistan would put a majority of Sikhs in India. (Amritsar had a non-Muslim majority and Gurdaspur a marginal Muslim majority.) To compensate for the exclusion of the Gurdaspur district, they included the entire Dinajpur district in the eastern zone of Pakistan, which similarly had a marginal Muslim majority. After receiving comments from John Thorne, member of the Executive Council in charge of Home affairs, Wavell forwarded the proposal to the Secretary of State. He justified the exclusion of the Amritsar district because of its sacredness to the Sikhs and that of Gurdaspur district because it had to go with Amritsar for 'geographical reasons'. The Secretary of State commended the proposal and forwarded it to the India and Burma Committee, saying, "I do not think that any better division than the one the Viceroy proposes is likely to be found".

Sikh concerns

The Sikh leader Master Tara Singh could see that any division of Punjab would leave the Sikhs divided between Pakistan and India. He espoused the doctrine of self-reliance, opposed the partition of India and called for independence on the grounds that no single religious community should control Punjab. Other Sikhs argued that just as Muslims feared Hindu domination the Sikhs also feared Muslim domination. Sikhs warned the British government that the morale of Sikh troops in the British Army would be affected if Pakistan was forced on them. Giani Kartar Singh drafted a scheme of a separate Sikh state if India was to be divided. During the Partition developments, Jinnah offered Sikhs to live in Pakistan with safeguards for their rights. Sikhs refused because they opposed the concept of Pakistan and also because they did not want to become a small minority within a Muslim majority. Vir Singh Bhatti distributed pamphlets for the creation of a separate Sikh state "Khalistan". Master Tara Singh wanted the right for an independent Khalistan to federate with either Hindustan or Pakistan. However, the Sikh state being proposed was for an area where neither religion was in absolute majority.''The Sikhs of the Punjab'', Volumes 2–3, J S Grewal, p. 176 Negotiations for the independent Sikh state had commenced at the end of World War II and the British initially agreed but the Sikhs withdrew this demand after pressure from Indian nationalists.''Ethnic Group's of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia'', James Minahan, p. 292 The proposals of the Cabinet Mission Plan had seriously jolted the Sikhs because while both the Congress and League could be satisfied the Sikhs saw nothing in it for themselves. as they would be subjected to a Muslim majority. Master Tara Singh protested this to Pethic-Lawrence on 5 May. By early September the Sikh leaders accepted both the long term and interim proposals despite their earlier rejection. The Sikhs attached themselves to the Indian state with the promise of religious and cultural autonomy.Final negotiations

In March 1946, the British government sent a Cabinet Mission to India to find a solution to resolve the conflicting demands of Congress and the Muslim League. Congress agreed to allow Pakistan to be formed with 'genuine Muslim areas'. The Sikh leaders asked for a Sikh state with

In March 1946, the British government sent a Cabinet Mission to India to find a solution to resolve the conflicting demands of Congress and the Muslim League. Congress agreed to allow Pakistan to be formed with 'genuine Muslim areas'. The Sikh leaders asked for a Sikh state with Ambala

Ambala () is a city and a municipal corporation in Ambala district in the state of Haryana, India, located on the border with the Indian state of Punjab (India), Punjab and in proximity to both states capital Chandigarh. Politically, Ambala ...

, Jalandher, Lahore

Lahore ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, second-largest city in Pakistan, after Karachi, and ...

Divisions with some districts from the Multan Division

Multan Division is an administrative division of Punjab Province, Pakistan. It was created during British colonial rule in South Asia in the 19th century. It includes 4 districts: Khanewal, Lodhran, Vehari and Multan and 15 Tehsils. Its reco ...

, which, however, did not meet the Cabinet delegates' agreement. In discussions with Jinnah, the Cabinet Mission offered either a 'smaller Pakistan' with all the Muslim-majority districts ''except Gurdaspur'' or a 'larger Pakistan' under the sovereignty of the Indian Union. The Cabinet Mission came close to success with its proposal for an Indian Union under a federal scheme, but it fell apart in the end because of Nehru's opposition to a heavily decentralised India.

In March 1947, Lord Mountbatten

Admiral of the Fleet (Royal Navy), Admiral of the Fleet Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (born Prince Louis of Battenberg; 25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979), commonly known as Lord Mountbatten, was ...

arrived in India as the next viceroy, with an explicit mandate to achieve the transfer of power before June 1948. Over ten days, Mountbatten obtained the agreement of Congress to the Pakistan demand except for the 13 eastern districts of Punjab (including Amritsar and Gurdaspur). However, Jinnah held out. Through a series of six meetings with Mountbatten, he continued to maintain that his demand was for six full provinces. He "bitterly complained" that the Viceroy was ruining his Pakistan by cutting Punjab and Bengal in half as this would mean a 'moth-eaten Pakistan'.

The Gurdaspur district remained a key contentious issue for the non-Muslims. Their members of the Punjab legislature made representations to Mountbatten's chief of staff Lord Ismay as well as the Governor telling them that Gurdaspur was a "non-Muslim district". They contended that even if it had a marginal Muslim majority of 51%, which they believed to be erroneous, the Muslims paid only 35% of the land revenue in the district.

In April, the Governor of Punjab Evan Jenkins wrote a note to Mountbatten proposing that Punjab be divided along Muslim and non-Muslim majority districts and proposed that a Boundary Commission be set up consisting of two Muslim and two non-Muslim members recommended by the Punjab Legislative Assembly. He also proposed that a British judge of the High Court be appointed as the chairman of the commission. Jinnah and the Muslim League continued to oppose the idea of partitioning the provinces, and the Sikhs were disturbed about the possibility of getting only 12 districts (without Gurdaspur). In this context, the Partition Plan of 3 June was announced with a notional partition showing 17 districts of Punjab in Pakistan and 12 districts in India, along with the establishment of a Boundary Commission to decide the final boundary. In Sialkoti's view, this was done mainly to placate the Sikhs.

Process and key people

A crude border had already been drawn up by Lord Wavell, theViceroy of India

The governor-general of India (1833 to 1950, from 1858 to 1947 the viceroy and governor-general of India, commonly shortened to viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom in their capacity as the Emperor of ...

prior to his replacement as Viceroy, in February 1947, by Lord Louis Mountbatten. In order to determine exactly which territories to assign to each country, in June 1947, Britain appointed Sir Cyril Radcliffe to chair two boundary commissions—one for Bengal and one for Punjab.

The commission was instructed to "demarcate the boundaries of the two parts of the Punjab on the basis of ascertaining the contiguous majority areas of Muslims and non-Muslims. In doing so, it will also take into account other factors." Other factors were undefined, giving Radcliffe leeway, but included decisions regarding "natural boundaries, communications, watercourses and irrigation systems", as well as socio-political consideration. Each commission also had four representatives—two from the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

and two from the Muslim League. Given the deadlock between the interests of the two sides and their rancorous relationship, the final decision was essentially Radcliffe's.

After arriving in India on 8 July 1947, Radcliffe was given just five weeks to decide on a border. He soon met with his fellow college alumnus Mountbatten and travelled to Lahore

Lahore ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, second-largest city in Pakistan, after Karachi, and ...

and Calcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

to meet with commission members, chiefly Nehru from the Congress and Jinnah, president of the Muslim League. He objected to the short time frame, but all parties were insistent that the line be finished by the 15 August British withdrawal from India. Mountbatten had accepted the post as Viceroy on the condition of an early deadline. The decision was completed just a couple of days before the withdrawal, but due to political considerations, not published until 17 August 1947, two days after the grant of independence to India and Pakistan.

Members of the commissions

Each boundary commission consisted of five people – a chairman ( Radcliffe), two members nominated by theIndian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

and two members nominated by the Muslim League.

The Bengal Boundary Commission consisted of justices C. C. Biswas, B. K. Mukherji, Abu Saleh Mohamed Akram and S.A.Rahman.

The members of the Punjab Commission were justices Mehr Chand Mahajan, Teja Singh, Din Mohamed and Muhammad Munir.

Problems in the process

Boundary-making procedures

All lawyers by profession, Radcliffe and the other commissioners had all of the polish and none of the specialized knowledge needed for the task. They had no advisers to inform them of the well-established procedures and information needed to draw a boundary. Nor was there time to gather the survey and regional information. The absence of some experts and advisers, such as the United Nations, was deliberate, to avoid delay. Britain's new Labour government "deep in wartime debt, simply couldn't afford to hold on to its increasingly unstable empire." "The absence of outside participants—for example, from the United Nations—also satisfied the British Government's urgent desire to save face by avoiding the appearance that it required outside help to govern—or stop governing—its own empire."Political representation

The equal representation given to politicians from Indian National Congress and the Muslim League appeared to provide balance, but instead created deadlock. The relationships were so tendentious that the judges "could hardly bear to speak to each other", and the agendas so at odds that there seemed to be little point anyway. Even worse, "the wife and two children of the Sikh judge in Lahore had been murdered by Muslims in Rawalpindi a few weeks earlier." In fact, minimizing the numbers of Hindus and Muslims on the wrong side of the line was not the only concern to balance. The Punjab Border Commission was to draw a border through the middle of an area home to the Sikh community. Lord Islay was rueful for the British not to give more consideration to the community who, in his words, had "provided many thousands of splendid recruits for the Indian Army" in its service for the crown in World War I. However, the Sikhs were militant in their opposition to any solution which would put their community in a Muslim ruled state. Moreover, many insisted on their own sovereign state, something no one else would agree to. Last of all, were the communities without any representation. The Bengal Border Commission representatives were chiefly concerned with the question of who would get Calcutta. The Buddhist tribes in theChittagong Hill Tracts

The Chittagong Hill Tracts (), often shortened to simply the Hill Tracts and abbreviated to CHT, refers to the three hilly districts within the Chittagong Division in southeastern Bangladesh, bordering India and Myanmar (Burma) in the east: Kh ...

in Bengal had no official representation and were left totally without information to prepare for their situation until two days after the partition.

Perceiving the situation as intractable and urgent, Radcliffe went on to make all the difficult decisions himself. This was impossible from inception, but Radcliffe seems to have had no doubt in himself and raised no official complaint or proposal to change the circumstances.

Local knowledge

Before his appointment, Radcliffe had never visited India and knew no one there. To the British and the feuding politicians alike, this neutrality was looked upon as an asset; he was considered to be unbiased toward any of the parties, except of course Britain. Only his private secretary, Christopher Beaumont, was familiar with the administration and life in Punjab. Wanting to preserve the appearance of impartiality, Radcliffe also kept his distance from Viceroy Mountbatten. No amount of knowledge could produce a line that would completely avoid conflict; already, "sectarian riots in Punjab and Bengal dimmed hopes for a quick and dignified British withdrawal". "Many of the seeds of postcolonial disorder in South Asia were sown much earlier, in a century and half of direct and indirect British control of large part of the region, but, as book after book has demonstrated, nothing in the complex tragedy of partition was inevitable."Haste and indifference

Radcliffe justified the casual division with thetruism

A truism is a claim that is so obvious or self-evident as to be hardly worth mentioning, except as a reminder or as a rhetorical or literary device, and is the opposite of a falsism.

In philosophy, a sentence which asserts incomplete truth con ...

that no matter what he did, people would suffer. The thinking behind this justification may never be known since Radcliffe "destroyed all his papers before he left India". He departed on Independence Day itself, before even the boundary awards were distributed. By his own admission, Radcliffe was heavily influenced by his lack of fitness for the Indian climate and his eagerness to depart India.

The implementation was no less hasty than the process of drawing the border. On 16 August 1947 at 5:00 pm, the Indian and Pakistani representatives were given two hours to study copies, before the Radcliffe award was published on 17 August.

Secrecy

To avoid disputes and delays, the division was done in secret. The final Awards were ready on 9 and 12 August, but not published until two days after the partition. According to Read and Fisher, there is some circumstantial evidence that Nehru and Patel were secretly informed of the Punjab Award's contents on 9 or 10 August, either through Mountbatten or Radcliffe's Indian assistant secretary. Regardless of how it transpired, the award was changed to put a salient portion of the non-Muslim majority Firozpur district (consisting of the two Muslim-majoritytehsil

A tehsil (, also known as tahsil, taluk, or taluka () is a local unit of administrative division in India and Pakistan. It is a subdistrict of the area within a Zila (country subdivision), district including the designated populated place that ser ...

s of Firozpur

Firozpur, (pronunciation: ɪroːzpʊr also known as Ferozepur, is a city on the banks of the Sutlej River in the Firozpur District of Punjab, India. After the Partition of India in 1947, it became a border town on the India–Pakistan bor ...

and Zira) east of the Sutlej canal within India's domain instead of Pakistan's. There were two apparent reasons for the switch: the area housed an army arms depot, and contained the headwaters of a canal which irrigated the princely state of Bikaner, which would accede to India.

Implementation

After the partition, the fledgling governments of India and Pakistan were left with all responsibility to implement the border. After visiting Lahore in August, Viceroy Mountbatten hastily arranged a Punjab Boundary Force to keep the peace around Lahore, but 50,000 men was not enough to prevent thousands of killings, 77% of which were in the rural areas. Given the size of the territory, the force amounted to less than one soldier per square mile. This was not enough to protect the cities much less the caravans of the hundreds of thousands of refugees who were fleeing their homes in what would become Pakistan. Both India and Pakistan were loath to violate the agreement by supporting the rebellions of villages drawn on the wrong side of the border, as this could prompt a loss of face on the international stage and require the British or the UN to intervene. Border conflicts led to three wars, in1947

It was the first year of the Cold War, which would last until 1991, ending with the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Events

January

* January–February – Winter of 1946–47 in the United Kingdom: The worst snowfall in the country i ...

, 1965

Events January–February

* January 14 – The First Minister of Northern Ireland and the Taoiseach of the Republic of Ireland meet for the first time in 43 years.

* January 20

** Lyndon B. Johnson is Second inauguration of Lynd ...

, and 1971 *

The year 1971 had three partial solar eclipses (Solar eclipse of February 25, 1971, February 25, Solar eclipse of July 22, 1971, July 22 and Solar eclipse of August 20, 1971, August 20) and two total lunar eclipses (February 1971 lunar eclip ...

, and the Kargil conflict of 1999.

Disputes

There were disputes regarding the Radcliffe Line's award of theChittagong Hill Tracts

The Chittagong Hill Tracts (), often shortened to simply the Hill Tracts and abbreviated to CHT, refers to the three hilly districts within the Chittagong Division in southeastern Bangladesh, bordering India and Myanmar (Burma) in the east: Kh ...

and the Gurdaspur district. Disputes also evolved around the districts of Malda, Khulna

Khulna (, ) is the third-largest city in Bangladesh, after Dhaka and Chittagong. It is the administrative centre of the Khulna District and the Khulna Division. It is the divisional centre of 10 districts of the division. Khulna is also the seco ...

, and Murshidabad

Murshidabad (), is a town in the Indian States and territories of India, state of West Bengal. This town is the headquarters of Lalbag subdivision of Murshidabad district. It is located on the eastern bank of the Hooghly river, Bhagirathi Riv ...

in Bengal and the sub-division of Karimganj

Karimganj, officially Sribhumi, is a town in the Karimganj district of the Indian States and territories of India, state of Assam. It is the administrative headquarters of the district.

Karimganj town is located at . The area of Karimganj Tow ...

of Assam.

In addition to Gurdaspur's Muslim majority tehsils, Radcliffe also gave the Muslim majority tehsils of Ajnala (Amritsar District

Amritsar district is one of the twenty three districts that make up the Indian state of Punjab, India, Punjab. Located in the Majha region of Punjab, the city of Amritsar is the headquarters of this district.

As of 2011, it is the second most ...

), Zira, Firozpur (in Firozpur District), Nakodar and Jullandur (in Jullandur District) to India instead of Pakistan. On the other hand, Chittagong Hill Tracts

The Chittagong Hill Tracts (), often shortened to simply the Hill Tracts and abbreviated to CHT, refers to the three hilly districts within the Chittagong Division in southeastern Bangladesh, bordering India and Myanmar (Burma) in the east: Kh ...

and Khulna

Khulna (, ) is the third-largest city in Bangladesh, after Dhaka and Chittagong. It is the administrative centre of the Khulna District and the Khulna Division. It is the divisional centre of 10 districts of the division. Khulna is also the seco ...

, with non-Muslim population of 97% and 51% respectively, were awarded to Pakistan.

Punjab

Firozpur District

Indian historians now accept that Mountbatten probably did influence the Firozpur award in India's favour. The headworks of River Beas, which later joins River Sutlej flowing into Pakistan, were located in Firozpur. Congress leader Nehru and Viceroy Mountbatten had lobbied Radcliffe that headworks should not go to Pakistan.Gurdaspur District

The Gurdaspur district was divided geographically by theRavi River

The Ravi River is a transboundary river in South Asia, flowing through northwestern India and eastern Pakistan, and is one of five major rivers of the Punjab region.

Under the Indus Waters Treaty of 1960, the waters of the Ravi and two oth ...

, with the Shakargarh tehsil on its west bank, and Pathankot

Pathankot () is a city and the district headquarters of the Pathankot district in Punjab, India. Pathankot is the sixth most populous city of Punjab, after Ludhiana, Amritsar, Jalandhar, Patiala and Bathinda. Its local government is a municipal ...

, Gurdaspur and Batala tehsils on its east bank. The Shakargarh tehsil, the biggest in size, was awarded to Pakistan. (It was subsequently merged into the Narowal district

Narowal District ( Punjabi and ) is a district in the province of Punjab, Pakistan. Narowal city is the capital of the district. During the British rule, Narowal was the town of Raya Khas tehsil of Sialkot District. Narowal District formed ...

of West Punjab.) The three eastern tehsils were awarded to India. (Pathankot was eventually made a separate district in East Punjab

East Punjab was a state of Dominion of India from 1947 until 1950. It consisted parts of the Punjab Province of British India that remained in India following the partition of the state between the new dominions of Pakistan and India by the ...

.) The division of the district was followed by a population transfer between the two nations, with Muslims leaving for Pakistan and Hindus and Sikhs arriving from there.

The entire district of Gurdaspur had a bare majority of 50.2% Muslims. (In the `notional' award attached to the Indian Independence Act, all of Gurdaspur district was marked as Pakistan with a 51.14% Muslim majority. In the 1901 census, the population of Gurdaspur district was 49% Muslim, 40% Hindu, and 10% Sikh.) The Pathankot tehsil was predominantly Hindu while the other three tehsils were Muslim majority. In the event, only Shakargarh was awarded to Pakistan.

Radcliffe explained that the reason for deviating from the notional award in the case of Gurdaspur was that the headwaters

The headwater of a river or stream is the geographical point of its beginning, specifically where surface runoff water begins to accumulate into a flowing channel of water. A river or stream into which one or many tributary rivers or streams flo ...

of the canals that irrigated the Amritsar district lay in the Gurdaspur district and it was important to keep them under one administration. Radcliffe might have sided with Lord Wavell's reasoning from February 1946 that Gurdaspur had to go with the Amritsar district, and the latter could not be in Pakistan due to its Sikh religious shrines. In addition, the railway line from Amritsar to Pathankot passed through the Batala and Gurdaspur tehsils. He further claimed that to compensate for the exclusion of the Gurdaspur district, they included the entire Dinajpur district in the eastern zone of Pakistan, which similarly had a marginal Muslim majority.

Pakistanis have alleged that the award of the three tehsils to India was a manipulation of the Award by Lord Mountbatten in an effort to provide a land route for India to Jammu and Kashmir. However, Shereen Ilahi points out that the land route to Kashmir was entirely within the Hindu-majority Pathankot tehsil. The award of the Batala and Gurdaspur tehsils to India did not affect the Kashmir land route.

Pakistani view on the award of Gurdaspur to India

Pakistan maintains that the Radcliffe Award was altered by Mountbatten; Gurdaspur was handed over to India and thus was manipulated the accession of Kashmir to India. In support of this view, some scholars claim the award to India "had little to do with Sikh demands but had much more to do with providing India a road link to Jammu and Kashmir." As per the 'notional' award that had already been put into effect for purposes of administration ad interim, all of Gurdaspur district, owing to its Muslim majority, was assigned to Pakistan. From 14 to 17 August, Mushtaq Ahmed Cheema acted as theDeputy Commissioner

A deputy commissioner is a police, income tax or administrative official in many countries. The rank is commonplace in police forces of Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth countries, usually ranking below the Commissioner.

Australia

In all Aust ...

of the Gurdaspur District, but when, after a delay of two days, it was announced that the major portion of the district had been awarded to India instead of Pakistan, Cheema left for Pakistan. The major part of Gurdaspur district, i.e. three of the four sub-districts had been handed over to India giving India practical land access to Kashmir. It came as a great blow to Pakistan. Jinnah and other leaders of Pakistan, and particularly its officials, criticized the award as 'extremely unjust and unfair'.

Muhammad Zafarullah Khan, who represented the Muslim League in July 1947 before the Radcliffe Boundary Commission, stated that the boundary commission was a farce. A secret deal between Mountbatten and Congress leaders had already been struck. Mehr Chand Mahajan, one of the two non-Muslim members of the boundary commission, in his autobiography, has acknowledged that when he was selected for the boundary commission, he was not inclined to accept the invitation as he believed that the commission was just a farce and that decisions were actually to be taken by Mountbatten himself. It was only under British pressure that the charges against Mountbatten of last minute alterations in the Radcliffe Award were not officially brought forward by Pakistani Government in the UN Security Council while presenting its case on Kashmir.

Zafrullah Khan states that, in fact, adopting the tehsil as a unit would have given Pakistan the Firozepur and Zira tehsils of the Firozpur District, the Jullundur and Nakodar tehsils of Jullundur district and the Dasuya tehsil of the Hoshiarpur district. The line so drawn would also give Pakistan the princely state of Kapurthala (which had a Muslim majority) and would enclose within Pakistan the whole of the Amritsar district of which only one tehsil, Ajnala, had a Muslim majority. It would also give Pakistan the Shakargarh, Batala and Gurdaspur tehsils of the Gurdaspur district. If the boundary went by Doabs, Pakistan could get not only the 16 districts which had already under the notional partition been put into West Punjab, including the Gurdaspur District, but also get the Kangra District in the mountains, which was about 93% Hindu and was located to the north and east of Gurdaspur. Or one could go by commissioners' divisions. Any of these units being adopted would have been more favourable to Pakistan than the present boundary line. The tehsil was the most favourable unit. But all of the aforementioned Muslim majority tehsils, with the exception of Shakargarh, were handed over to India while Pakistan didn't receive any Non-Muslim majority district or tehsil in Punjab. Zafruallh Khan states that Radcliffe used district, tehsil, thana, and even village boundaries to divide Punjab in such a way that the boundary line was drawn much to the prejudice of Pakistan. However, while Muslims formed about 53% of the total population of Punjab in 1941, Pakistan received around 58% of the total area of the Punjab, including more of the most fertile parts.

According to Zafrullah Khan, the assertion that the award of the Batala and Gurdaspur tehsils to India did not 'affect' Kashmir is far-fetched. If Batala and Gurdaspur had gone to Pakistan, Pathankot tehsil would have been isolated and blocked. Even though it would have been possible for India to get access to Pathankot through the Hoshiarpur district, it would have taken quite long time to construct the roads, bridges and communications that would have been necessary for military movements.

Assessments on the 'Controversial Award of Gurdaspur to India and the Kashmir Dispute'

Stanley Wolpert

Stanley Albert Wolpert (December 23, 1927 – February 19, 2019) was an American historian, Indologist, and author on the political and intellectual history of modern India and PakistanDr. Stanley Wolpert's UCLA Faculty homepage and wrote fict ...

writes that Radcliffe in his initial maps awarded Gurdaspur district to Pakistan but one of Nehru's and Mountbatten's greatest concerns over the new Punjab border was to make sure that Gurdaspur would not go to Pakistan, since that would have deprived India of direct road access to Kashmir. As per "The Different Aspects of Islamic Culture", a part of UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

's Histories flagship project, recently disclosed documents of the history of the partition reveal British complicity with the top Indian leadership to wrest Kashmir from Pakistan. Alastair Lamb, based on the study of recently declassified documents, has convincingly proven that Mountbatten, in league with Nehru, was instrumental in pressurizing Radcliffe to award the Muslim-majority district of Gurdaspur in East Punjab to India which could provide India with the only possible access to Kashmir. Andrew Roberts believes that Mountbatten cheated over India-Pak frontier and states that if gerrymandering took place in the case of Firozepur, it is not too hard to believe that Mountbatten also pressurized Radcliffe to ensure that Gurdaspur wound up in India to give India road access to Kashmir.

Perry Anderson

Francis Rory Peregrine "Perry" Anderson (born 11 September 1938) is a British intellectual, political philosopher, historian and essayist. His work ranges across historical sociology, intellectual history, and cultural analysis. What unites An ...

states that Mountbatten, who was officially supposed to neither exercise any influence on Radcliffe nor to have any knowledge of his findings, intervened behind the scenes – probably at Nehru's behest – to alter the award. He had little difficulty in getting Radcliffe to change his boundaries to allot the Muslim-majority district of Gurdaspur to India instead of Pakistan, thus giving India the only road access from Delhi to Kashmir.

However, some British works suggest that the 'Kashmir State was not in anybody's mind' when the Award was being drawn and that even the Pakistanis themselves had not realized the importance of Gurdaspur to Kashmir until the Indian forces actually entered Kashmir. Both Mountbatten and Radcliffe, of course, have strongly denied those charges. It is impossible to accurately quantify the personal responsibility for the tragedy of Kashmir as the Mountbatten papers relating to the issue at the India Office Library and records are closed to scholars for an indefinite period.

Bengal

Chittagong Hill Tracts

TheChittagong Hill Tracts

The Chittagong Hill Tracts (), often shortened to simply the Hill Tracts and abbreviated to CHT, refers to the three hilly districts within the Chittagong Division in southeastern Bangladesh, bordering India and Myanmar (Burma) in the east: Kh ...

had a majority non-Muslim population of 97% (most of them Buddhists

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or 5th century BCE. It is the world's fourth ...

), but was given to Pakistan. The Chittagong Hill Tracts People's Association (CHTPA) petitioned the Bengal Boundary Commission that, since the CHTs were inhabited largely by non-Muslims, they should remain within India. The Chittagong Hill Tracts was an excluded area since 1900 and was not part of Bengal. It had no representative at the Bengal Legislative Assembly in Calcutta, since it was not part of Bengal. Since they had no official representation, there was no official discussion on the matter, and many on the Indian side assumed the CHT would be awarded to India.

On 15 August 1947, Chakma and other indigenous Buddhists celebrated independence day by hoisting Indian flag in Rangamati, the capital of Chittagong Hill Tracts. When the boundaries of Pakistan and India were announced by radio on 17 August 1947, they were shocked to know that the Chittagong Hill Tracts had been awarded to Pakistan. The Baluch Regiment of the Pakistani Army entered Chittagong Hill Tracts a week later and lowered the Indian flag at gun point. The rationale of giving the Chittagong Hill Tracts to Pakistan was that they were inaccessible to India and to provide a substantial rural buffer to support Chittagong

Chittagong ( ), officially Chattogram, (, ) (, or ) is the second-largest city in Bangladesh. Home to the Port of Chittagong, it is the busiest port in Bangladesh and the Bay of Bengal. The city is also the business capital of Bangladesh. It ...

(now in Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

), a major city and port; advocates for Pakistan forcefully argued to the Bengal Boundary Commission that the only approach was through Chittagong.

The indigenous people sent a delegation led by Sneha Kumar Chakma to Delhi to seek help from the Indian leadership. Sneha Kumar Chakma contacted Sardar Patel by phone. Sardar Patel was willing to help, but insisted Sneha Kumar Chakma seek assistance from Prime Minister Pandit Nehru. But Nehru refused to help fearing that military conflict for Chittagong Hill Tracts might draw the British back to India.

Malda District

Another disputed decision made by Radcliffe was the division of theMalda district

Malda district, also spelt Maldah or Maldaha (, , often ), is a district in West Bengal, India. The capital of the Bengal Sultanate, Gauda and Pandua, was situated in this district. Mango, jute and silk are the most notable products of this ...

of Bengal

Bengal ( ) is a Historical geography, historical geographical, ethnolinguistic and cultural term referring to a region in the Eastern South Asia, eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. The region of Benga ...

. The district overall had a slight Muslim majority, but was divided and most of it, including Malda town, went to India. The district remained under East Pakistan administration for 3–4 days after 15 August 1947. It was only when the award was made public that the Pakistani flag was replaced by the Indian flag in Malda.

Khulna and Murshidabad Districts

The Khulna District (with a marginal Hindu majority of 51%) was given to East Pakistan in lieu of theMurshidabad district

Murshidabad district is a district in the Indian state of West Bengal. Situated on the left bank of the river Ganges, the district is very fertile. Covering an area of and having a population 7.103 million (according to 2011 census), it ...

(with a 70% Muslim majority), which went to India. However, the Pakistani flag remained hoisted in Murshidabad for three days until it was replaced by the Indian flag on the afternoon of 17 August 1947.

Karimganj

TheSylhet

Sylhet (; ) is a Metropolis, metropolitan city in the north eastern region of Bangladesh. It serves as the administrative center for both the Sylhet District and the Sylhet Division. The city is situated on the banks of the Surma River and, as o ...

district of Assam

Assam (, , ) is a state in Northeast India, northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra Valley, Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . It is the second largest state in Northeast India, nor ...

joined Pakistan in accordance with a referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

. However, the Karimganj

Karimganj, officially Sribhumi, is a town in the Karimganj district of the Indian States and territories of India, state of Assam. It is the administrative headquarters of the district.

Karimganj town is located at . The area of Karimganj Tow ...

sub-division (with a Muslim majority) was separated from Sylhet and given to India, where it became a district in 1983. As of the 2001 Indian census, Karimganj district now has a Muslim majority of 52.3%.

Legacy

Legacy and historiography

As a part of a series on borders, the explanatory news site Vox featured an episode looking at "the ways that the Radcliffe line changed Punjab, and its everlasting effects" including disrupting "a centuries-old Sikh pilgrimage" and separating "Punjabi people of all faiths from each other."Air Defence

In the decades following Partition, the Radcliffe Line gained additional importance beyond its geopolitical function. During the Cold War period and subsequent Indo-Pakistani conflicts, the Indian and Pakistan Air Force established radar stations along key stretches of the border to provide early warning of aerial incursions. These radar units became a vital part of air defence grid, particularly in the Punjab and Jammu sectors during the 1965 and 1971 wars.Artistic depictions

One notable depiction is '' Drawing the Line'', written by British playwrightHoward Brenton

Howard John Brenton FRSL (born 13 December 1942) is an English playwright and screenwriter, often ranked alongside contemporaries such as Edward Bond, Caryl Churchill, and David Hare.

Early years

Brenton was born in Portsmouth, Hampshire, so ...

. On his motivation for writing the play, Brenton said he first became interested in the story of the Radcliffe Line while holidaying in India and hearing stories from people whose families had fled across the new line.

Defending his portrayal of Cyril Radcliffe as a man who struggled with his conscience, Brenton said, "There were clues that Radcliffe had a dark night of the soul in the bungalow: he refused to accept his fee, he did collect all the papers and draft maps, took them home to England and burnt them. And he refused to say a word, even to his family, about what happened. My playwright's brain went into overdrive when I discovered these details."

Indian filmmaker Ram Madhvani created a nine-minute short film where he explored the plausible scenario of Radcliffe regretting the line he drew. The film was inspired by W. H. Auden's poem on the Partition.

Visual artists Zarina Hashmi, Salima Hashmi

Salima Hashmi (; born 1942) is a Pakistani painter, artist, former college professor, anti-nuclear weapons activist and former caretaker minister in Sethi caretaker ministry. She has served for four years as a professor and the dean of Nationa ...

, Nalini Malini, Reena Saini Kallat and Pritika Chowdhry have created drawings, prints and sculptures depicting the Radcliffe Line.

See also

* India–Pakistan border * Curzon line * Indo-Bangladesh enclaves * McMahon Line *Durand Line

The Durand Line (; ; ), also known as the Afghanistan–Pakistan border, is a international border between Afghanistan and Pakistan in South Asia. The western end runs to the border with Iran and the eastern end to the border with China.

The D ...

* Sykes-Picot Agreement

* Rajkahini

Notes

References

Sources

* * * ** * * Mansergh, Nicholas, ed. ''The Transfer of Power, 1942–7''. (12 volumes) * * * * *Further reading

* India: Volume XI: The Mountbatten Viceroyalty-Announcement and Reception of 3 June Plan, 31 May-7 July 1947. Reviewed by Wood, J.R. "Dividing the Jewel: Mountbatten and the Transfer of Power to India and Pakistan". ''Pacific Affairs'', Vol. 58, No. 4 (Winter, 1985–1986), pp. 653–662. * Berg, E., and van Houtum, HRouting borders between territories, discourses, and practices (p. 128)

* Chester, Lucy P

''Borders and Conflict in South Asia: The Radcliffe Boundary Commission and the Partition of Punjab''.

Manchester UP, 2009. * Collins, L., and Lapierre, D. (1975) '' Freedom at Midnight''. * Collins, L., and Lapierre, D

''Mountbatten and the Partition of India''

Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, 1983. * Heward, E. ''The Great and the Good: A Life of Lord Radcliffe''. Chichester: Barry Rose Publishers, 1994. * * Moon, P

The Transfer of Power, 1942–7: Constitutional Relations Between Britain and India: Volume X: The Mountbatten Viceroyalty – Formulation of a Plan

22 March–30 May 1947

Review "Dividing the Jewel" at JSTOR

* Moon, Blake, D., and Ashton, S

The Transfer of Power, 1942–7: Constitutional Relations Between Britain and India: Volume XI: The Mountbatten Viceroyalty Announcement and Reception of the 3rd June Plan 31 May–7 July 1947

Review "Dividing the Jewel" at JSTOR

* Smitha, F

MacroHistory website, 2001. * Tunzelmann, A. ''Indian Summer''. Henry Holt. * Wolpert, S. (1989). ''A New History of India'', 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

External links

{{Pakistan Movement Bangladesh–India border Geography of India India–Pakistan border Pakistan Movement Partition of India Eponymous border lines Territorial evolution of Bangladesh