Rachel Workman MacRobert on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rachel, Lady MacRobert, née Workman (23 March 1884 – 1 September 1954) was a geologist, cattle breeder and an active feminist. Born in Massachusetts to an influential family, she was educated in England and Scotland. She was elected to Fellowship of the

Rachel and MacRobert married on 7 July 1911 at a

Rachel and MacRobert married on 7 July 1911 at a

Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

, one of the first three women admitted. Her scientific studies included petrology

Petrology () is the branch of geology that studies rocks and the conditions under which they form. Petrology has three subdivisions: igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary petrology. Igneous and metamorphic petrology are commonly taught together ...

and mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proces ...

in Sweden and her first academic paper was published in 1911. She married Sir Alexander MacRobert

Sir Alexander MacRobert, 1st Baronet (21 May 1854 – 22 June 1922) was a self-made millionaire from Aberdeen. He came from a working-class background and left school when he was twelve to start his working life sweeping floors in Stoneywood Pap ...

, a wealthy self-made Scottish millionaire, and had three sons with him. He was endowed with a knighthood in 1910 and a baronetcy in 1922 but died later that year. Lady MacRobert's sons all pre-deceased her: the eldest in a flying accident in 1938, and the other two died in action during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

serving with the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

. On the death of her husband she became a director of the British India Corporation

British India Corporation Limited (BIC) is a central public sector undertaking under the ownership of the Ministry of Textiles, Government of India. The cpsu produces textiles for use by civilians and the Indian armed forces. It manufactures t ...

, the conglomerate he had founded.

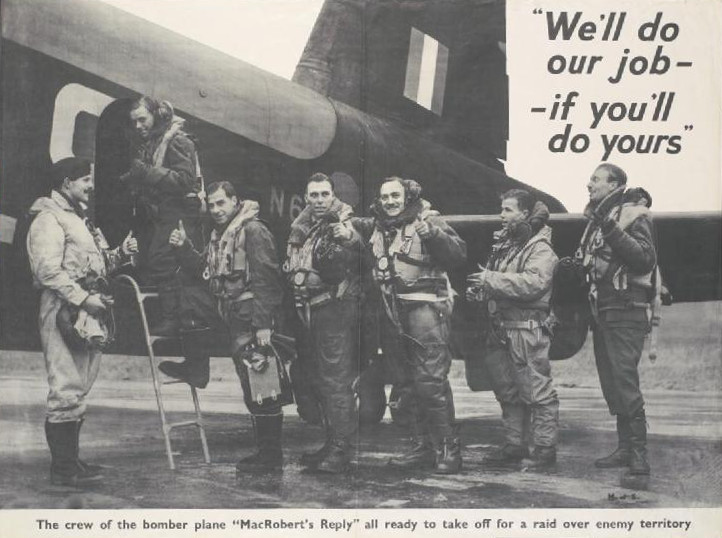

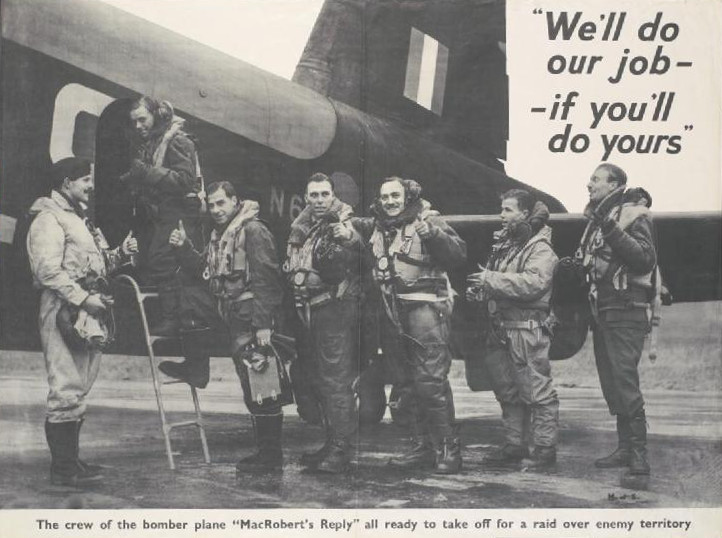

To commemorate her sons, Rachel paid for a Short Stirling

The Short Stirling was a British four-engined heavy bomber of the Second World War. It has the distinction of being the first four-engined bomber to be introduced into service with the Royal Air Force (RAF).

The Stirling was designed during t ...

bomber named "MacRobert's Reply

The MacRobert Baronetcy, of Douneside in the County of Aberdeen, was a title in the Baronetage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 5 April 1922 for Alexander MacRobert, a self-made millionaire. He was succeeded by his eldest son Alasdair in ...

", and four Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness by ...

s.

In 1943 she created the MacRobert Trust, a charity that continues to support the RAF among other institutions. It created the MacRobert Award

The MacRobert Award is regarded as the leading prize recognising UK innovation in engineering by corporations. The winning team receives a gold medal and a cash sum of £50,000.

The annual award process begins with an invitation to companies to ...

for engineering, today awarded by the Royal Academy of Engineering

The Royal Academy of Engineering (RAEng) is the United Kingdom's national academy of engineering.

The Academy was founded in June 1976 as the Fellowship of Engineering with support from Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, who became the first senior ...

.

Background and early life

Born on 23 March 1894, inWorcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is a city and county seat of Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, England, the city's population was 206,518 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the second-List of cities i ...

, Rachel was the eldest child of Fanny Bullock Workman

Fanny Bullock Workman (January 8, 1859 – January 22, 1925) was an American geographer, cartographer, explorer, travel writer, and mountaineer, notably in the Himalayas. She was one of the first female professional mountaineers; she not only e ...

and her husband William Hunter Workman; the couple also had a son, Siegfried, born in 1889. Fanny and William were well educated and from prominent, wealthy New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

families. Fanny received a large inheritance when her father, Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

, died in 1882 and the family fortune was further boosted by a significant bequest from William's father in 1885. The family moved to Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label=Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth larg ...

when Rachel was five-years-old in 1889 claiming it would be beneficial to William's "debilitating" health issues. Following the move, he made a prompt return to good health and the couple escalated their interests in travelling and exploring the world. Rachel and her brother were left in Dresden to be cared for by nurses during their parents' frequent trips away. Siegfried died on 26 June 1893 after contracting pneumonia. Fanny's preference for travelling over the responsibilities of motherhood intensified a few months after the funeral and Rachel was despatched to England to be educated at The Cheltenham Ladies' College

Cheltenham Ladies' College is an independent boarding and day school for girls aged 11 to 18 in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England. Consistently ranked as one of the top all-girls' schools nationally, the school was established in 1853 to p ...

.

After Cheltenham, Rachel attended Royal Holloway College

Royal Holloway, University of London (RHUL), formally incorporated as Royal Holloway and Bedford New College, is a public research university and a constituent college of the federal University of London. It has six schools, 21 academic departm ...

, an institution founded to provide a university education for women. In 1911 she graduated with a second class Honours degree

Honours degree has various meanings in the context of different degrees and education systems. Most commonly it refers to a variant of the undergraduate bachelor's degree containing a larger volume of material or a higher standard of study, or ...

in geology having spent a year, 1907 until 1908, undertaking a special study of the subject at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

. Rachel remained in contact with her parents and while returning to England from a trip to India with them in 1909 she met Sir Alexander MacRobert

Sir Alexander MacRobert, 1st Baronet (21 May 1854 – 22 June 1922) was a self-made millionaire from Aberdeen. He came from a working-class background and left school when he was twelve to start his working life sweeping floors in Stoneywood Pap ...

. Commonly referred to as Mac, he was born in Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

to working class parents. He left school when he was twelve but continued his education by attending evening classes. Thirty years older than Rachel, he was born in 1854; when they met he was a widower who had already made a significant fortune building up woollen mills in Cawnpore, or Kanpur

Kanpur or Cawnpore ( /kɑːnˈpʊər/ pronunciation (help·info)) is an industrial city in the central-western part of the state of Uttar Pradesh, India. Founded in 1207, Kanpur became one of the most important commercial and military stations o ...

as it is now known, where he had worked since early 1884. MacRobert received a knighthood in the New Year's Honours list in 1910 by which time the pair had an established relationship; Rachel refused to attend the ceremony with him at Buckingham Palace declaring: "I will bow to no man."

Marriage and family

Rachel and MacRobert married on 7 July 1911 at a

Rachel and MacRobert married on 7 July 1911 at a Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

Meeting House in York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

. Neither of Rachel's parents attended the ceremony. Marriage did not prevent her continuing her studies as she attended the Imperial College

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

in London. While there she undertook research into petrology

Petrology () is the branch of geology that studies rocks and the conditions under which they form. Petrology has three subdivisions: igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary petrology. Igneous and metamorphic petrology are commonly taught together ...

and mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proces ...

in Scotland and Sweden, publishing papers on the subject in 1911. She further enhanced her education by attending the Christiania Mineralogisk Institutet, undertaking a post-graduate research course. Her husband devoted most of his time continuing to build his conglomerate in India but eventually Rachel would not live there and referred to it as "that nasty land". While she was in India she continued her geological research at the Kolar Gold Fields

Kolar Gold Fields (K.G.F.) is a mining region in K.G.F. taluk (township), Kolar district, Karnataka, India. It is headquartered in Robertsonpet, where employees of Bharat Gold Mines Limited (BGML) and BEML Limited (formerly Bharat Earth Move ...

. She soon predominantly divided her time between her studies, European travel and managing the estate at Tarland

Tarland (Gaelic: ''Turlann'') is a village in Aberdeenshire, Scotland and is located northwest of Aboyne, and west of Aberdeen. Population 720 (2016).

Tarland is home to the Culsh Earth House, an Iron Age below-ground dwelling that otherwise ...

in Aberdeenshire, which Sir Alexander had acquired in 1905 to complement the small farm he bought nearby in 1888. Rachel did reluctantly travel to India to attend ceremonial events like the Delhi Durbar

The Delhi Durbar ( lit. "Court of Delhi") was an Indian imperial-style mass assembly organized by the British at Coronation Park, Delhi, India, to mark the succession of an Emperor or Empress of India. Also known as the Imperial Durbar, it was ...

in mid-December 1911.

The couple had three children, all boys: Alasdair, the eldest was born on 11 July 1912; Roderic on 8 May 1915; and the youngest, Iain, on 19 April 1917. The birth of the children did not curtail Sir Alexander's commitment and time spent in India resulting in Rachel being left to care for the children alone. Despite this, she managed to continue her scientific investigations undertaking research at the Eildon Hill

Eildon Hill lies just south of Melrose, Scotland in the Scottish Borders, overlooking the town. The name is usually pluralised into "the Eildons" or "Eildon Hills", because of its triple peak. The high eminence overlooks Teviotdale to the Sout ...

s in the Scottish borders which was published in 1914.

Rachel's mother was a strong proponent of women's rights and the suffragette movement, an advocacy Rachel shared. Invitations to garden parties in support of the National Union of Women Workers, or the National Council of Women of Great Britain

The National Council of Women exists to co-ordinate the voluntary efforts of women across Great Britain. Founded as the National Union of Women Workers, it said that it would "promote sympathy of thought and purpose among the women of Great Brita ...

as it is now known, were readily accepted and Rachel hosted luncheon parties for suffragette coordinators. When suffragettes were involved in violent protests in Aberdeen during 1913 against the conditions imposed on women Rachel justified actions like explosives being thrown by stating: "Girls have no sort of life under present social conditions and the wickedness of men at large".

Middle years

Sir Alexander was raised to a baronet at the beginning of 1922, choosing to be named Sir Alexander MacRobert of Cawnpore and Cromar of the County of Aberdeen. He returned to Scotland in April that year but was in poor health; he had a fatal heart attack on 22 June 1922 at Douneside. Rachel was left a widow, albeit a rich one, with three boys aged five, seven and ten. Legal difficulties arose over the settlement of Sir Alexander's will due to unrest in India combined with a lengthy acrimonious disagreement with tax inspectors in the UK. His British assets after the payment of death duties amounted to £264,000, the equivalent of over £13.7 million . By 1920 Sir Alexander had built up a portfolio of six companies; he had amalgamated these to form theBritish India Corporation

British India Corporation Limited (BIC) is a central public sector undertaking under the ownership of the Ministry of Textiles, Government of India. The cpsu produces textiles for use by civilians and the Indian armed forces. It manufactures t ...

. After his death Rachel assumed the role of director, a position she held until her eldest son, Alasdair, became chairman in 1937. The three boys did not enjoy robust health; this led to Rachel founding a herd of Friesian dairy cattle at Douneside to produce better quality milk for them.

Additional contributions to geology

During her academic career Rachel took a particular interest in glacial geomorphology and petrology. She studied the occurrence of calcite in the igneous rocks on the Alno Island of southern Norway, and also studied the petrography ofEildon Hill

Eildon Hill lies just south of Melrose, Scotland in the Scottish Borders, overlooking the town. The name is usually pluralised into "the Eildons" or "Eildon Hills", because of its triple peak. The high eminence overlooks Teviotdale to the Sout ...

, Scotland. Soon after her time at Imperial College

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

, Rachel published her first paper in 1911, "Calcite as a Primary Constituent of Igneous Rock". Active within the geology research community, Rachel attended the International Geological Congress in 1910 and 1913. At her attendance in 1913 at the Annual General Meeting of the Royal Geological Society an attempt was made to eject her; it did not succeed. As one of the many women to make great academic and social strides in the field of geology, Rachel played a key role in the formal integration of women as Fellows of the Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

in 1919. In 1938 she was elected as a life fellow of the Royal Society of Arts

The Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA), also known as the Royal Society of Arts, is a London-based organisation committed to finding practical solutions to social challenges. The RSA acronym is used m ...

.

References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:MacRobert, R 1884 births 1954 deaths People from Worcester, Massachusetts Fellows of the Geological Society of London Alumni of Royal Holloway, University of London People educated at Cheltenham Ladies' College Scottish women geologists Scottish philanthropists American emigrants to Scotland American emigrants to England Wives of baronets 20th-century British philanthropists