Rabbinic Authority on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rabbinic authority in

Rabbinic authority in

Rabbinic authority in

Rabbinic authority in Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the ...

relates to the theological and communal authority attributed to rabbis

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as '' semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form o ...

and their pronouncements in matters of Jewish law

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Judaism, Jewish religious laws which is derived from the Torah, written and Oral Tora ...

. The extent of rabbinic authority differs by various Jewish groups and denominations throughout history. The origins of rabbinic authority in Judaism is understood as originally linked to the High Court of ancient Israel and Judah

The history of ancient Israel and Judah begins in the Southern Levant during the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. "Israel" as a people or tribal confederation (see Israelites) appears for the first time in the Merneptah Stele, an inscripti ...

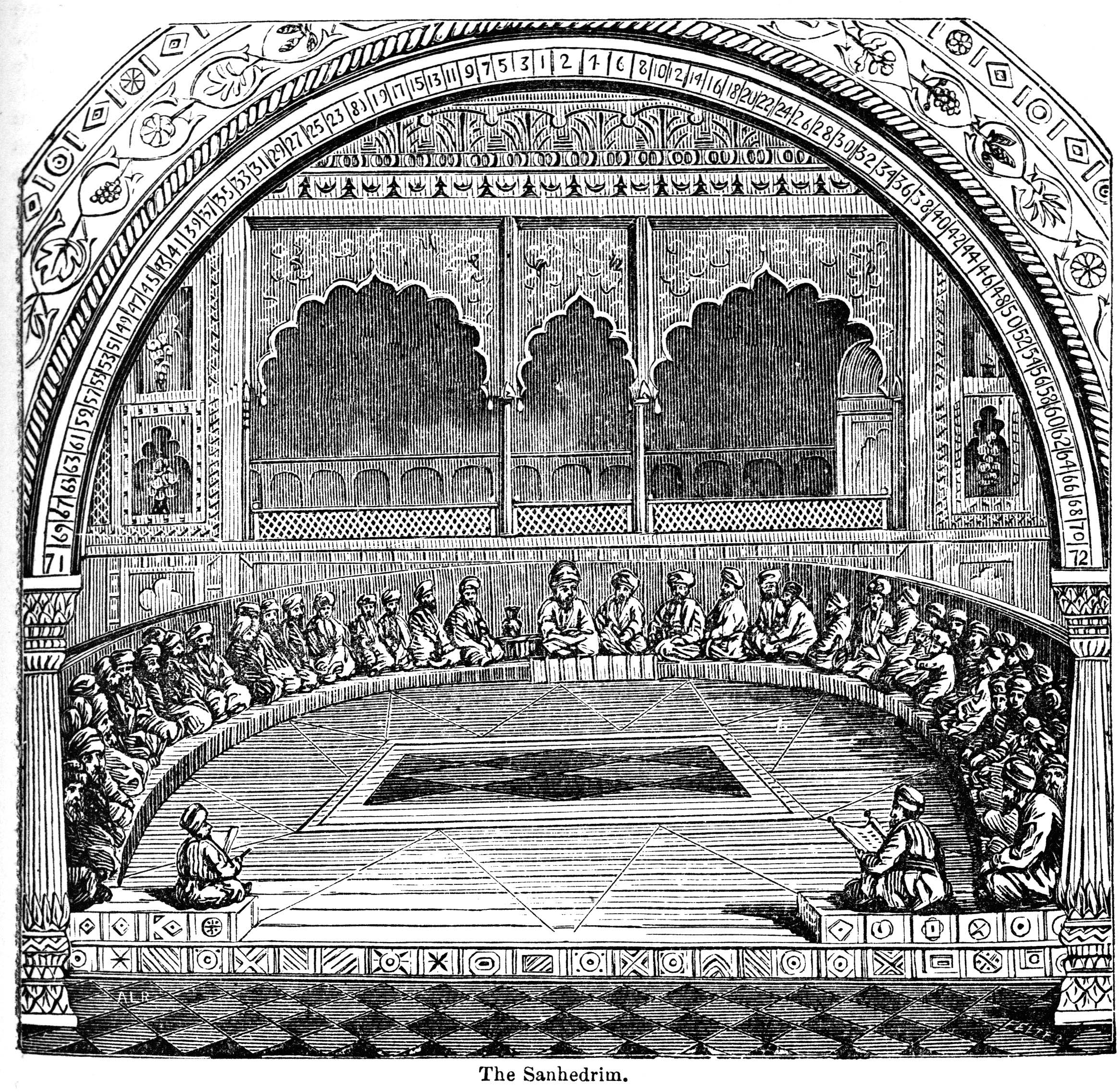

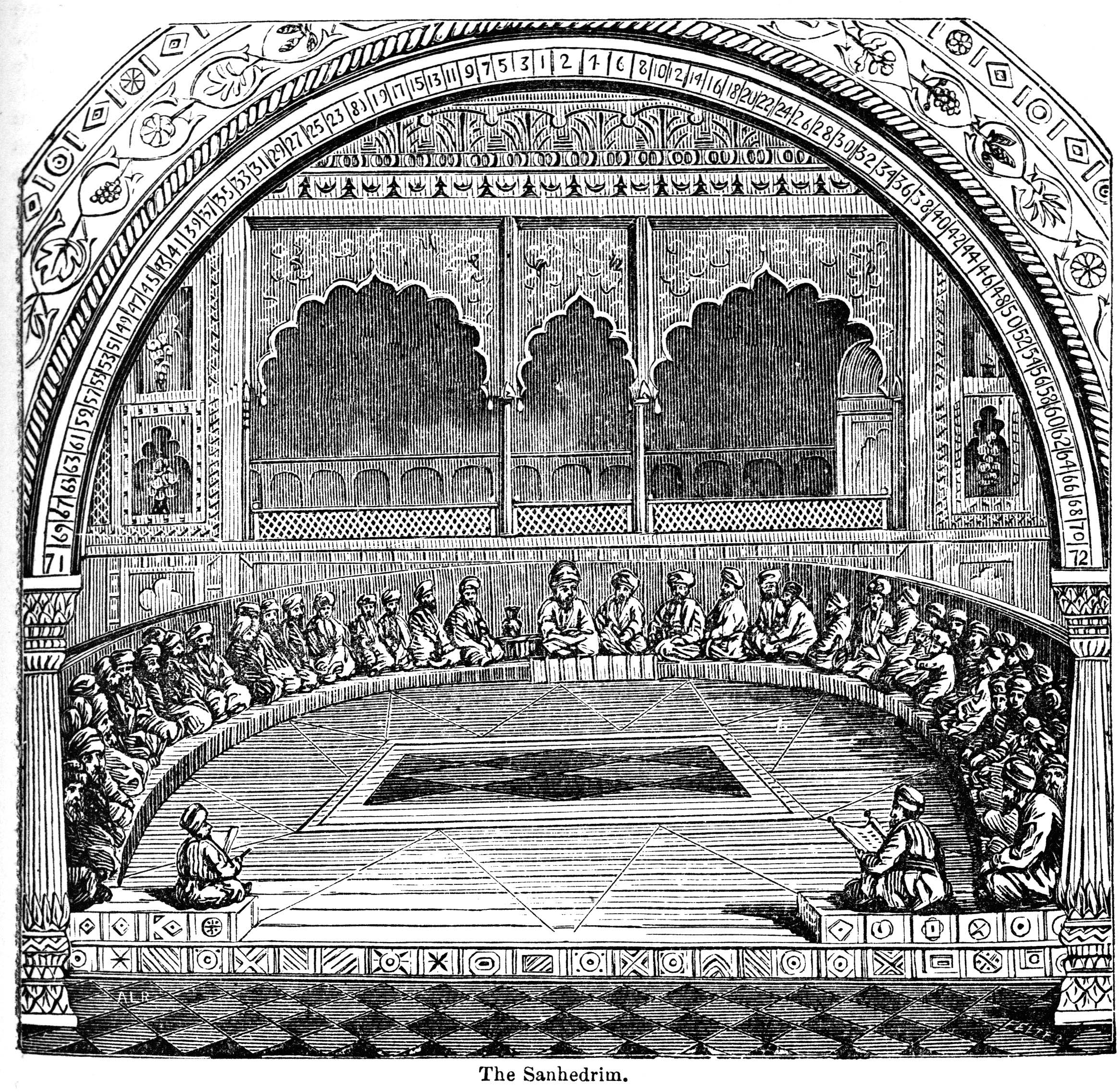

, known as the Sanhedrin

The Sanhedrin (Hebrew and Aramaic: סַנְהֶדְרִין; Greek: , ''synedrion'', 'sitting together,' hence 'assembly' or 'council') was an assembly of either 23 or 71 elders (known as "rabbis" after the destruction of the Second Temple), ap ...

. Scholars understand that the extent of rabbinic authority, historically, would have related to areas of Jewish civil, criminal, and ritual law, while rabbinic positions that relate to non-legal matters, such as Jewish philosophy

Jewish philosophy () includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. Until modern ''Haskalah'' (Jewish Enlightenment) and Jewish emancipation, Jewish philosophy was preoccupied with attempts to reconcile ...

would have been viewed as non-binding.Turkel, E. (1993). The nature and limitations of rabbinic authority. Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought, 27(4), 80-99. Rabbinic authority also distinguished the practice of Judaism by the Pharisees

The Pharisees (; he, פְּרוּשִׁים, Pərūšīm) were a Jewish social movement and a school of thought in the Levant during the time of Second Temple Judaism. After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, Pharisaic beliefs bec ...

(i.e., Rabbinic Judaism

Rabbinic Judaism ( he, יהדות רבנית, Yahadut Rabanit), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, or Judaism espoused by the Rabbanites, has been the mainstream form of Judaism since the 6th century CE, after the codification of the Babylonian ...

) to the religious practice of the Sadducees

The Sadducees (; he, צְדוּקִים, Ṣədūqīm) were a socio-religious sect of Jewish people who were active in Judea during the Second Temple period, from the second century BCE through the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. Th ...

and the Qumran

Qumran ( he, קומראן; ar, خربة قمران ') is an archaeological site in the West Bank managed by Israel's Qumran National Park. It is located on a dry marl plateau about from the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea, near the Israeli ...

sect. This concept is linked with the acceptance of rabbinic law

In its primary meaning, the Hebrew word (; he, מִצְוָה, ''mīṣvā'' , plural ''mīṣvōt'' ; "commandment") refers to a commandment commanded by God to be performed as a religious duty. Jewish law () in large part consists of discus ...

, which separates Judaism from other offshoot religions such as Samaritanism

Samaritanism is the Abrahamic, monotheistic, ethnic religion of the Samaritan people, an ethnoreligious group who, alongside Jews, originate from the ancient Israelites.

Its central holy text is the Samaritan Pentateuch, which Samaritans ...

and Karaite Judaism

Karaite Judaism () or Karaism (, sometimes spelt Karaitism (; ''Yahadut Qara'it''); also spelt Qaraite Judaism, Qaraism or Qaraitism) is a Jewish religious movement characterized by the recognition of the written Torah alone as its supreme au ...

. In contemporary Orthodox Judaism

Orthodox Judaism is the collective term for the traditionalist and theologically conservative branches of contemporary Judaism. Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Written and Oral, as revealed by God to Moses on M ...

, the concept is sometimes referred to as da'as Torah (or da'at Torah) ( he, דעת תורה, literally "knowledge of Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the s ...

"), and the notion of rabbinic authority in this context is often extended beyond the confines of Jewish law, but to a variety of personal, social and political matters.

Origins

Biblical injuction

One of the commandments in Hebrew Bible relate the establishment of a High Court, known as theSanhedrin

The Sanhedrin (Hebrew and Aramaic: סַנְהֶדְרִין; Greek: , ''synedrion'', 'sitting together,' hence 'assembly' or 'council') was an assembly of either 23 or 71 elders (known as "rabbis" after the destruction of the Second Temple), ap ...

, in the Temple in Jerusalem. In this context, there is a biblical injunction against straying from the rulings of the Sanhedrin. This precept is referred to as "''lo tasur''" ( he, לא תסור)Sacks, Y. (1993). The mizvah of "lo tasur:" Limits and Applications. ''Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought,'' ''27''(4), 49-60. Retrieved August 27, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23260885. and is sourced from the Book of Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy ( grc, Δευτερονόμιον, Deuteronómion, second law) is the fifth and last book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called (Hebrew: hbo, , Dəḇārīm, hewords Moses.html"_;"title="f_Moses">f_Moseslabel=none)_and_th ...

which states:

According to Jewish scholars, only when the majority of the Sanhedrin (or another centralized court) that represents the entire Jewish people formally votes does the Biblical injunction of ''lo tasur'' apply. Additionally, this precept only applies to the early rabbinic positions from the era of the Mishna and Talmud, but not to the rabbis of later generations. Community leaders similarly share some of the rights of the Sanhedrin, but this applies only where the majority of the community accepts their authority. Individuals who are not community members are not required to follow the decisions of community leaders. The medieval rabbinic authority, Moses Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

, lists the injunction of ''lo tasur'' as the 312th biblical commandment (of the 613 commandments

The Jewish tradition that there are 613 commandments ( he, תרי״ג מצוות, taryag mitzvot) or mitzvot in the Torah (also known as the Law of Moses) is first recorded in the 3rd century AD, when Rabbi Simlai mentioned it in a sermon that i ...

). Aside from the injunction of ''lo tasur'' there is a separate Biblical commandment to respect and honor Torah scholars, even if one disagrees with their views.

The authority founded in rabbinic law is framed in context of the biblical commandments (''mitzvot

In its primary meaning, the Hebrew word (; he, מִצְוָה, ''mīṣvā'' , plural ''mīṣvōt'' ; "commandment") refers to a commandment commanded by God to be performed as a religious duty. Jewish law () in large part consists of discus ...

'') and termed as commandments as well. These are listed as "biblical and rabbinic commandments" ( ''mitzvot de'oraita'' and ''mitzvot derabanan''). This new category distinguished the rabbinic authority of the rabbis from the laws of the Qumranite and Sadducean groups of ancient Israel. And while the rabbinic commandments are presented as authoritative, the rabbis acknowledge that biblical commandments override rabbinic commandments.

Treatment in Talmud

Diverging historical views on the actual extent of rabbinic authority in the Talmudic period and are described in terms of maximalism and minimalism. Maximalists view rabbinic authority as extending over Jewish religious and civic life as it existed under Roman rule. Minimalists view rabbinic authority under Roman rule as greatly limited with the rabbis unable to enforce their rulings. Additionally, some scholars suggest that Talmudic rabbis produced many texts concerning the destroyed Jewish Temple which in turn bolstered rabbinic authority in the post-Temple period. In Jewish sources, the topic of rabbinic authority appears frequently. Beyond the general topic of the authority of the Sanhedrin, other discussions also arise. Rabbinic authority is treated in the Babylonian Talmud as occurring, at times, in opposition to divine authority. This conflict appears in a well-known text in the Babylonian Talmud (Baba Metzia 59b) regarding the sageEliezer ben Hurcanus

Eliezer ben Hurcanus or Hyrcanus ( he, אליעזר בן הורקנוס) was one of the most prominent Sages (tannaim) of the 1st and 2nd centuries in Judea, disciple of Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai Avot of Rabbi Natan 14:5 and colleague of Gamalie ...

who declared Oven of Akhnai to be ritually pure against the majority view. According to the passage, neither Rabbi Eliezer's attempts to use reason nor his use of miracles and divine voices are accepted by the rabbis. This passage is understood as the right of rabbinic authority over both the minority opinion as well as over divine authority (or that the Torah is "not in Heaven

Not in Heaven (לֹא בַשָּׁמַיִם הִיא, ''lo ba-shamayim hi'') is a phrase found in a Biblical verse, , which encompasses the passage's theme, and takes on additional significance in rabbinic Judaism.

In its literal or plain meanin ...

"). There is some additional deliberation based on readings of the Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud ( he, תַּלְמוּד יְרוּשַׁלְמִי, translit=Talmud Yerushalmi, often for short), also known as the Palestinian Talmud or Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century ...

and the Sifre

Sifre ( he, סִפְרֵי; ''siphrēy'', ''Sifre, Sifrei'', also, ''Sifre debe Rab'' or ''Sifre Rabbah'') refers to either of two works of ''Midrash halakha'', or classical Jewish legal biblical exegesis, based on the biblical books of Numbers a ...

as to whether the obligation is to obey just the original Sanhedrin in Jerusalem or subsequent rabbinical courts that are constituted in a similar fashion such as the Council of Jamnia

The Council of Jamnia (presumably Yavneh in the Holy Land) was a council purportedly held late in the 1st century CE to finalize the canon of the Hebrew Bible. It has also been hypothesized to be the occasion when the Jewish authorities decided ...

(known in rabbinical texts as the ''Beth Din

A beit din ( he, בית דין, Bet Din, house of judgment, , Ashkenazic: ''beis din'', plural: batei din) is a rabbinical court of Judaism. In ancient times, it was the building block of the legal system in the Biblical Land of Israel. Today, it ...

'' of Yavne

Yavne ( he, יַבְנֶה) or Yavneh is a city in the Central District of Israel. In many English translations of the Bible, it is known as Jabneh . During Greco-Roman times, it was known as Jamnia ( grc, Ἰαμνία ''Iamníā''; la, Iamnia) ...

). The Talmud also offers scenarios where rabbinic authority is disregarded, in this case where the congregation are certain of the court's error. Treatment of this topic is taken up at length in the Talmudic tractate of ''Horayot

Horayot ( he, הוֹרָיוֹת; "Decisions") is a tractate in Seder Nezikin in the Talmud.

In the Mishnah, this is the tenth and last tractate in Nezikin; in the Babylonian Talmud the ninth tractate; in the Jerusalem Talmud the eighth. It consi ...

''. An additional concept is the instance when a Jewish elder refuses to concede to the majority opinion, such an elder is termed ''zaken mamre'' ("a rebellious elder"). A concept similar to the notion of rabbinic authority is the value of placing faith in the Jewish sages (''emunat chachamim''). This topic is listed as the twenty-third of a list of forty-eight attributes through which the wisdom of the Jewish tradition is acquired.

Basis for authority

The practical basis for rabbinic authority involves the acceptance of the rabbinic individual and their scholarly credentials. In practical terms, Jewish communities and individuals commonly proffer allegiance to the authority of the rabbi they have chosen. Such a rabbinic leader is sometimes called the "Master of the Locale" (''mara d'atra''). Jewish individuals may acknowledge the authority of other rabbis but will defer legal decisions to the ''mara d'atra''. Rabbinic authority may be derived from scholarly achievements within a meritocratic system. Rabbinic authority may be viewed as based on credentials in the form of the institutionally approved ordination (''semikhah

Semikhah ( he, סמיכה) is the traditional Jewish name for rabbinic ordination.

The original ''semikhah'' was the formal "transmission of authority" from Moses through the generations. This form of ''semikhah'' ceased between 360 and 425 C ...

''). This approval and authority allows rabbis to engage in the legal process of Jewish ritual (''halakha

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

'') and to prescribe legal rulings.

Challenges in the medieval era

In themedieval era

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

and in the time period that immediately followed in the early modern period, there arose three major challenges to rabbinic authority that led to fissures, divisions, and resistance to the power which the rabbis previously claimed. The first major challenge of this period arose from the rise of rationalism and its impact on Jewish theology. The second major challenge involved the aftermath of the Spanish expulsion and the forced conversions from that period that occurred to conversos

A ''converso'' (; ; feminine form ''conversa''), "convert", () was a Jew who converted to Catholicism in Spain or Portugal, particularly during the 14th and 15th centuries, or one of his or her descendants.

To safeguard the Old Christian po ...

and their descendants in Europe and the New World. The third challenge involved the popularity of Jewish mysticism

Academic study of Jewish mysticism, especially since Gershom Scholem's ''Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism'' (1941), distinguishes between different forms of mysticism across different eras of Jewish history. Of these, Kabbalah, which emerged in 1 ...

and the events that surrounded the advent of Sabbateanism

The Sabbateans (or Sabbatians) were a variety of Jewish followers, disciples, and believers in Sabbatai Zevi (1626–1676),

a Sephardic Jewish rabbi and Kabbalist who was proclaimed to be the Jewish Messiah in 1666 by Nathan of Gaza.

Vast n ...

.

Orthodox Judaism and ''da'as Torah''

In some communities withinOrthodox Judaism

Orthodox Judaism is the collective term for the traditionalist and theologically conservative branches of contemporary Judaism. Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Written and Oral, as revealed by God to Moses on M ...

, rabbinic authority is viewed as extensive, according to which Orthodox Jews should seek the input of rabbinic scholars not just on matters of Jewish law, but on all important life matters, on the grounds that knowledge of the Torah aids everything in life. The linkage of the Orthodox notion of rabbinic authority is known as ''da'as Torah'' and is a contested matter and the views are partly split along communal lines within Orthodoxy. Rabbinic leaders from Haredi

Haredi Judaism ( he, ', ; also spelled ''Charedi'' in English; plural ''Haredim'' or ''Charedim'') consists of groups within Orthodox Judaism that are characterized by their strict adherence to ''halakha'' (Jewish law) and traditions, in oppos ...

and Hasidic

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism (Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of contem ...

communities view the concept as inextricably linked to the centuries of Jewish tradition. Within modern Orthodox Judaism

Modern Orthodox Judaism (also Modern Orthodox or Modern Orthodoxy) is a movement within Orthodox Judaism that attempts to synthesize Jewish values and the observance of Jewish law with the secular, modern world.

Modern Orthodoxy draws on sever ...

, many rabbis and scholars view the matter as a modern development that can be traced to changes in Jewish communal life in the nineteenth century. Within Orthodoxy, the topic of religious authority also significantly relates to the notion of stringiencies relating to Jewish law and custom.Friedman, M. (2004). Halachic rabbinic authority in the modern open society. Jewish Religious Leadership, Image, and Reality, 2, 757-770. The concept of ''da'as Torah'' may have originated as an extension of the role of the Rebbe

A Rebbe ( yi, רבי, translit=rebe) or Admor ( he, אדמו״ר) is the spiritual leader in the Hasidic movement, and the personalities of its dynasties.Heilman, Samuel"The Rebbe and the Resurgence of Orthodox Judaism."''Religion and Spiritua ...

in Hasidic Judaism

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism (Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Judaism, Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory ...

. The espoused belief in the Haredi

Haredi Judaism ( he, ', ; also spelled ''Charedi'' in English; plural ''Haredim'' or ''Charedim'') consists of groups within Orthodox Judaism that are characterized by their strict adherence to ''halakha'' (Jewish law) and traditions, in oppos ...

branch of Orthodox Judaism is that Jews, both individually and collectively, should seek out the views of the prominent religious scholars. And the views of rabbis apply to matters of Jewish law as well as matters in all aspects of community life. Although the authority of rabbinic views concerning extralegal matters is not universally accepted in modern Orthodoxy, other factions of Orthodoxy lobby for these rabbinic stances to be considered by their moderate coreligionists.Eleff, Z., & Farber, S. (2020). Antimodernism and Orthodox Judaism's Heretical Imperative: An American Religious Counterpoint. ''Religion and American Culture'', ''30''(2), 237-272.

While the notion of ''da'as Torah'' is viewed by Haredi rabbis as a long-established tradition within the Judaism, modern Orthodox scholars argue that the Haredi claim is a revisionist one. According to modern Orthodox scholars, although the term "''da'as Torah''" has been used in the past, the connotations of absolute rabbinic authority under this banner occurs only in the decades that follow the establishment of the Agudas Yisrael party in Eastern Europe. Additionally, Orthodox scholars who elaborate the Haredi position are careful to distinguish between rabbinic authority in legal versus extralegal matters. Whereas in declaring matters of Jewish law rabbinic authorities are required to render decisions based on precedents, sources, and Talmudic principles of analysis, a rabbinic authority has greater latitude when declaring ''da'as Torah'' than when defining a halakhic opinion. While a halakhic opinion requires legal justification from recognized sources, simple ''da'as Torah'' is regarded as being of a more subtle nature and requires no clear legal justification or explicit grounding in earlier sources. Thereby, different authorities may offer diametrically opposed opinions based on their own understanding. Some scholars argue that with the rise of modernity, the wider availability of secular knowledge, and a reduction of commitment to religion, members of traditional Jewish communities raised challenges to the leadership role of the rabbis. The Haredi position of ''da'as Torah'' is possibly a counter reaction to the changes linked to modernity. This counter reaction also may give way to a view that the rabbinic authority is of an infallible nature. According to other scholars, the notion of ''da'as Torah'' is specifically linked to the rise of the Agudat Yisrael

Agudat Yisrael ( he, אֲגוּדָּת יִשְׂרָאֵל, lit., ''Union of Israel'', also transliterated ''Agudath Israel'', or, in Yiddish, ''Agudas Yisroel'') is a Haredi Jewish political party in Israel. It began as a political party re ...

political party during the interwar period in Poland. Additionally, it may have arisen as part of the Haredi

Haredi Judaism ( he, ', ; also spelled ''Charedi'' in English; plural ''Haredim'' or ''Charedim'') consists of groups within Orthodox Judaism that are characterized by their strict adherence to ''halakha'' (Jewish law) and traditions, in oppos ...

rejectionist stance to modernity, in opposition the approach of modern Orthodox Jewish leaders.

Applications

* Israeli politics — The concept of rabbinic authority as presented in the modernState of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

contains a political dimension. Rabbinic authority as expressed in Israeli politics varies by religious party and faction. The expression of the ''da'as Torah'' concept is most strongly found in the use of a rabbinic council that guides the Haredi political parties in Israel. The influence of rabbinic authority is somewhat lessened in the moderate faction of the Religious Zionist

Religious Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת דָּתִית, translit. ''Tziyonut Datit'') is an ideology that combines Zionism and Orthodox Judaism. Its adherents are also referred to as ''Dati Leumi'' ( "National Religious"), and in Israel, the ...

parties. Some researchers view secular media in Israel as posing a unique challenge to Orthodox rabbinic authority over their communities and political parties. To mitigate this challenge, Orthodox communities have formed media outlets run exclusively for Orthodox populations.

* Impact on health — Mental health professionals who treat ultra-Orthodox patients have encountered the challenge of individuals who typically resort to rabbinical authority to advise on a range of personal matters. These mental health workers advocate for a joint effort in treating such patients as the mental health worker cannot advise regarding religious matters but neither can rabbinic authorities dispense health advice on complex issues. One common example of mental health where this dilemma is expressed is with regards to obsessive–compulsive disorder

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is a mental and behavioral disorder in which an individual has intrusive thoughts and/or feels the need to perform certain routines repeatedly to the extent where it induces distress or impairs general ...

(OCD). It was also estimated that a significant proportion of ultra-Orthodox patients seeking treatment had first sought spiritual responses from rabbis, making their first treatment choice to be an appeal to rabbinic authority and wisdom. In the case of OCD, the discussion of the disorder appears in modern rabbinical responsa

''Responsa'' (plural of Latin , 'answer') comprise a body of written decisions and rulings given by legal scholars in response to questions addressed to them. In the modern era, the term is used to describe decisions and rulings made by scholars i ...

(''she'elot u-teshuvot'').

* Internet-based rabbinic authority — With the advent of the internet, rabbis have been sought out for rabbinic advice. However, the online setting of seeking internet-based authority poses the risk where the typical respect conferred upon rabbis is diminished. The increased tendency for petitioners to respond to rabbinic decisions on internet-based communication platforms may inadvertently lead to disrespecting rabbinic authority.

Conservative Judaism

InConservative Judaism

Conservative Judaism, known as Masorti Judaism outside North America, is a Jewish religious movement which regards the authority of ''halakha'' (Jewish law) and traditions as coming primarily from its people and community through the generatio ...

, the injunction of ''lo tasur'' is generally understood as solely referring to the authority of the Sanhedrin Court in Jerusalem and therefore does not apply to later rabbinic authorities for either their rulings or customs. However, Conservative rabbis also understand that the injunction of ''lo tasur'' may follow two alternative applications in relation to the question of majority opinions in Jewish law. The first stance rests on the metaphysical belief that there is divinely bestowed authority on the majority decisions produced by the rabbinical court. The second stance relies on a theological stance regarding the form of transmission of Torah in the post-prophetic age and which allows for a lesser degree of authority to be associated with the rabbinical majority. For both of these views, there are implications that concern the rights of rabbinical minorities and of Jewish individuals who are not of the same view as the majority of the rabbinical court. And while each view can be maintained within Conservative Judaism and associated with the emphasis on the use of rabbinic majorities, it is argued that the second view is mostly aligned with the tradition of the Conservative movement that allows for greater powers for the rabbinic minority.

Gendered authority

Since the 1980s, Conservative Judaism has ordainedwomen rabbis

Women rabbis are individual Jewish women who have studied Jewish Law and received rabbinical ordination. Women rabbis are prominent in Progressive Jewish denominations, however, the subject of women rabbis in Orthodox Judaism is more complex. Al ...

and admitted them into the Conservative rabbinate where they serve a full range of rabbinic callings. This has led some scholars to consider how gender relates to rabbinic authority. An initial presumption among members of the movement's theological institution was that gender inequality within the rabbinate would cease to be a major issue once greater numbers of women would receive ordination. That perspective would align with a view that most aspects of rabbinic authority in Conservative Judaism would be similar for both male and female rabbis. However, research that examined the barriers to women gaining formal positions in congregations has lent itself to a more critical view of the gendered barriers for women rabbis to be recognized as rabbinic authorities.

Hasidic Judaism

InHasidic

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism (Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of contem ...

circles, a ''Rebbe

A Rebbe ( yi, רבי, translit=rebe) or Admor ( he, אדמו״ר) is the spiritual leader in the Hasidic movement, and the personalities of its dynasties.Heilman, Samuel"The Rebbe and the Resurgence of Orthodox Judaism."''Religion and Spiritua ...

'' or ''Tzaddik

Tzadik ( he, צַדִּיק , "righteous ne, also ''zadik'', ''ṣaddîq'' or ''sadiq''; pl. ''tzadikim'' ''ṣadiqim'') is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous, such as biblical figures and later spiritual masters. The ...

'' is often regarded as having extraordinary spiritual powers and is sought for personal advice in all pursuits of life by his followers. The devotion to the Tzaddik involves setting aside the Hasid's intellect and reason as a precondition for a blessing of abundance Another factor in the faith in the Tzaddik involves the role of the Tzaddik as the mediator between God and the Hasid.Rubin, E. (2020). Questions of love and truth: New perspectives on the controversy between R. Avraham of Kalisk and R. Shneur Zalman of Liady. ''Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies'', ''38''(3), 242-286. Faith in the power of the Tzaddik was common to all branches of the Hasidic movement with the words and advise of the Tzaddik viewed by the Hasidim as of the same stature of prophecy and from which the Hasid may not deviate. Nevertheless, the are differences between Hasidic groups on the degree of resistance on the part of the Tzaddik with Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi

Shneur Zalman of Liadi ( he, שניאור זלמן מליאדי, September 4, 1745 – December 15, 1812 Adoption of the Gregorian calendar#Adoption in Eastern Europe, O.S. / 18 Elul 5505 – 24 Tevet 5573) was an influential Lithuanian Jews, Li ...

of Chabad

Chabad, also known as Lubavitch, Habad and Chabad-Lubavitch (), is an Orthodox Jewish Hasidic dynasty. Chabad is one of the world's best-known Hasidic movements, particularly for its outreach activities. It is one of the largest Hasidic group ...

and Rabbi Nachman of Breslov

Nachman of Breslov ( he, רַבִּי נַחְמָן מִבְּרֶסְלֶב ''Rabbī'' ''Naḥmān mīBreslev''), also known as Reb Nachman of Bratslav, Reb Nachman Breslover ( yi, רבי נחמן ברעסלאווער ''Rebe Nakhmen Breslover'' ...

objecting to their followers request for blessings for material success.

See also

* List of religious titles in JudaismReferences

{{Jews and Judaism Haredi Judaism Israeli cultureAuthority

In the fields of sociology and political science, authority is the legitimate power of a person or group over other people. In a civil state, ''authority'' is practiced in ways such a judicial branch or an executive branch of government.''The N ...