RMS Victorian on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

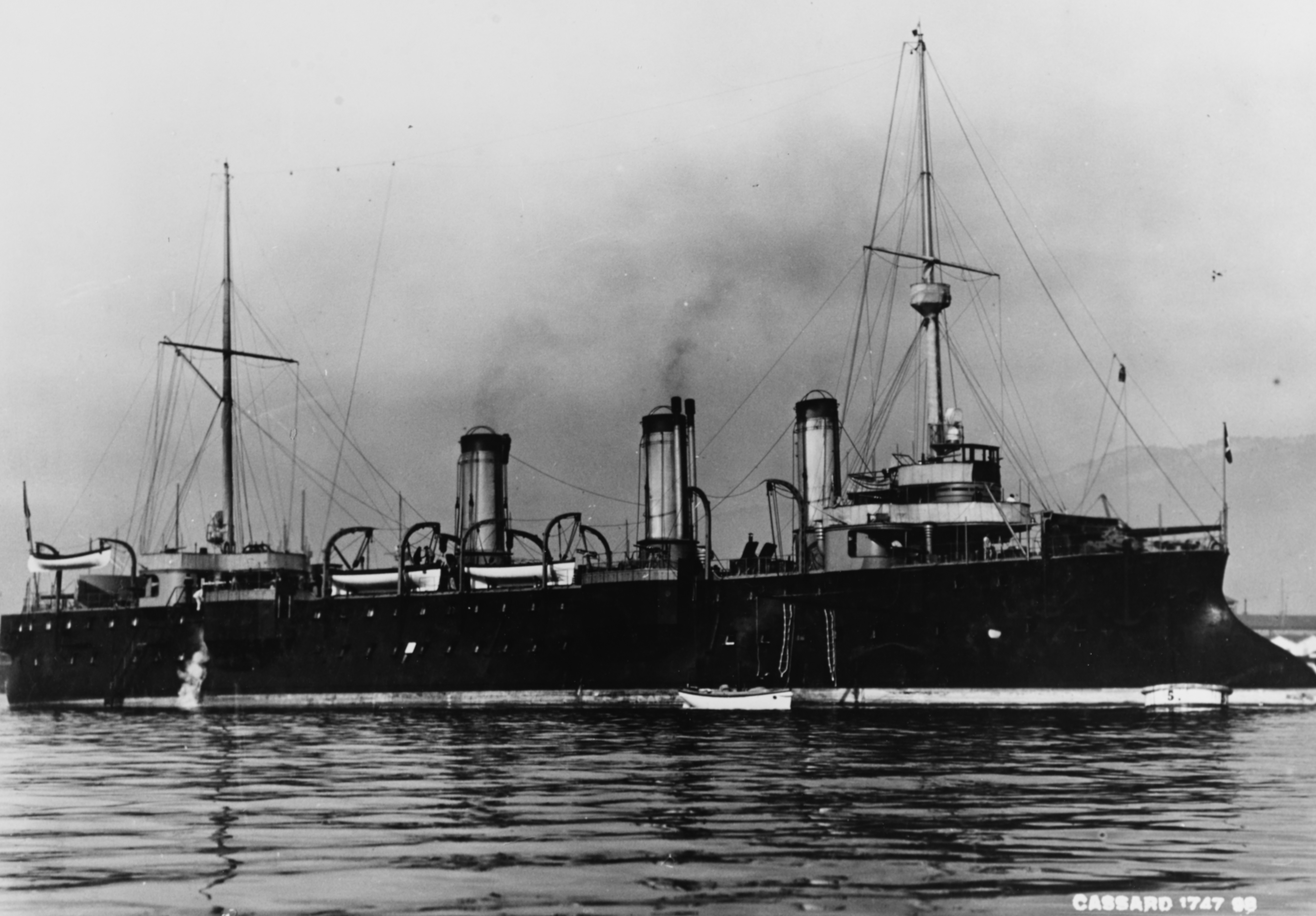

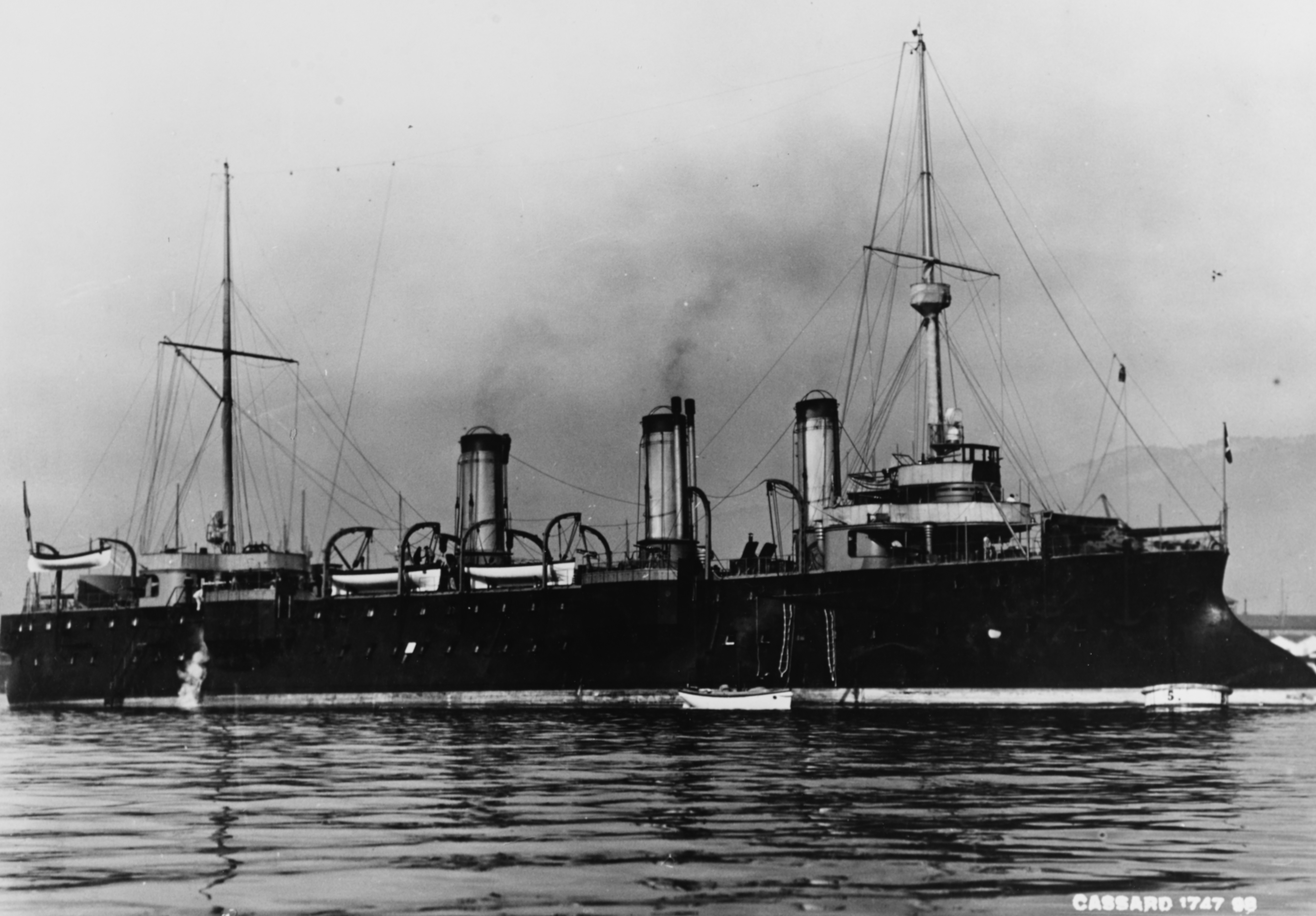

RMS ''Victorian'' was the world's first

''Victorian'' served with the 9th Cruiser Squadron from September 1914 until March 1915. In September 1914 she was ordered to the coast of

''Victorian'' served with the 9th Cruiser Squadron from September 1914 until March 1915. In September 1914 she was ordered to the coast of

In the mid-1920s Canadian Pacific put ''Marloch'' in reserve, but she often saw service.

On 26 June 1925 ''Marloch'' was in the

In the mid-1920s Canadian Pacific put ''Marloch'' in reserve, but she often saw service.

On 26 June 1925 ''Marloch'' was in the

turbine

A turbine ( or ) (from the Greek , ''tyrbē'', or Latin ''turbo'', meaning vortex) is a rotary mechanical device that extracts energy from a fluid flow and converts it into useful work. The work produced by a turbine can be used for generating ...

-powered ocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).

Ca ...

. She was designed as a transatlantic

Transatlantic, Trans-Atlantic or TransAtlantic may refer to:

Film

* Transatlantic Pictures, a film production company from 1948 to 1950

* Transatlantic Enterprises, an American production company in the late 1970s

* ''Transatlantic'' (1931 film) ...

liner and mail ship for Allan Line

The Allan Shipping Line was started in 1819, by Captain Alexander Allan of Saltcoats, Ayrshire, trading and transporting between Scotland and Montreal, a route which quickly became synonymous with the Allan Line. By the 1830s the company had off ...

and launched in 1904.

''Victorian'' was built in Belfast. She had a sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

, '' Virginian'', which was built in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

and launched four months later.

Throughout the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

''Victorian'' was an armed merchant cruiser (AMC). In 1918 she also carried cargo and troops.

In 1920 she returned to civilian service with the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

, but in 1921 the British Government chartered her as a troop ship

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

. In 1922 Canadian Pacific renamed her ''Marloch''. She was scrapped in 1929 after a quarter of a century of successful service.

Background

Charles Parsons had demonstrated the speed of his marine steam turbines in ''Turbinia

''Turbinia'' was the first steam turbine-powered steamship. Built as an experimental vessel in 1894, and easily the fastest ship in the world at that time, ''Turbinia'' was demonstrated dramatically at the Spithead Navy Review in 1897 and set ...

'' launched in 1894 and their reliability in the Clyde Clyde may refer to:

People

* Clyde (given name)

* Clyde (surname)

Places

For townships see also Clyde Township

Australia

* Clyde, New South Wales

* Clyde, Victoria

* Clyde River, New South Wales

Canada

* Clyde, Alberta

* Clyde, Ontario, a tow ...

excursion steamer launched in 1901. But ''King Edward''s fuel costs were higher than those of her reciprocating-engined and as a result so were her fares. Passengers accepted the higher cost on ''King Edward''s day trips down the Clyde, but ocean liner companies did not know whether passengers, cargo customers and post offices would accept the higher cost on Atlantic crossings lasting several days.

Canadian Pacific entered the North Atlantic Trade by buying Elder Dempster Lines

Elder Dempster Lines was a UK shipping company that traded from 1932 to 2000, but had its origins in the mid-19th century.

Founders

Alexander Elder

Alexander Elder was born in Glasgow in 1834. He was the son of David Elder, who for many ye ...

' Beaver Line subsidiary early in 1903. Allan Line responded by ordering a pair of new express liners. Allan Line originally planned to order conventional twin-screw ships with reciprocating steam engine

A reciprocating engine, also often known as a piston engine, is typically a heat engine that uses one or more reciprocating pistons to convert high temperature and high pressure into a rotating motion. This article describes the common featu ...

s, but in October 1903 it announced that it had ordered a pair of ships with turbines driving three screws as on ''King Edward''.

On 28 January 1904, seven months before ''Victorian'' was launched, the Government of Canada

The government of Canada (french: gouvernement du Canada) is the body responsible for the federal administration of Canada. A constitutional monarchy, the Crown is the corporation sole, assuming distinct roles: the executive, as the ''Crown ...

announced it had awarded Allan Line a transatlantic mail contract. Four Allan Line ships were to provide a regular scheduled service: the liners ''Bavarian'' and ''Tunisian'', and the new ''Victorian'' and ''Virginian''. The subsidy would be $5,000 per trip for ''Bavarian'' and ''Tunisian'', and $10,000 per trip for each of the new turbine ships.

Design

''Victorian''s propulsion system was a scaled-up version of ''King Edward''s. She had threescrews

A screw and a bolt (see '' Differentiation between bolt and screw'' below) are similar types of fastener typically made of metal and characterized by a helical ridge, called a ''male thread'' (external thread). Screws and bolts are used to fa ...

. ''Victorian''s Scotch marine boiler

A "Scotch" marine boiler (or simply Scotch boiler) is a design of steam boiler best known for its use on ships.

The general layout is that of a squat horizontal cylinder. One or more large cylindrical furnaces are in the lower part of the boiler ...

s had coal-fired furnaces whose smoke was exhausted through a large single funnel. Her boilers fed steam at to the high-pressure Parsons turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turb ...

driving her centre shaft. Exhaust steam from the high-pressure turbine drove the low-pressure Parsons turbines on her port and starboard

Port and starboard are nautical terms for watercraft and aircraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the bow (front).

Vessels with bilateral symmetry have left and right halves which are ...

(wing) shafts. All three screws were driven directly at turbine speed.

''Victorian'' was long, her beam was and her depth was . Her tonnage

Tonnage is a measure of the cargo-carrying capacity of a ship, and is commonly used to assess fees on commercial shipping. The term derives from the taxation paid on ''tuns'' or casks of wine. In modern maritime usage, "tonnage" specifically ref ...

s were and . She had orlop deck

The orlop is the lowest deck in a ship (except for very old ships). It is the deck or part of a deck where the cables are stowed, usually below the water line.

According to the ''Oxford English Dictionary'', the word descends from Dutch

Dut ...

s fore and aft of her machinery spaces, and three full decks in her hull with berths for 240 second-class passengers on the main and upper deck and up to 940 in third class. Atop the hull, her forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is the phrase " be ...

was followed by forward holds, a long superstructure with cabins and public saloons for 470 first-class passengers on the bridge and promenade decks, an after hold, and a poop deck

In naval architecture, a poop deck is a deck that forms the roof of a cabin built in the rear, or " aft", part of the superstructure of a ship.

The name originates from the French word for stern, ''la poupe'', from Latin ''puppis''. Thus ...

. Her holds had space for 8,000 tons of cargo and included refrigerated space for perishable produce.

Building and performance

Workman, Clark and Company

Workman, Clark and Company was a shipbuilding company based in Belfast.

History

The business was established by Frank Workman and George Clark in Belfast in 1879 and incorporated Workman, Clark and Company Limited in 1880. By 1895 it was the UK ...

built ''Victorian'' in Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

, launching her on 25 August 1904. On 5 December it was reported that on sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s she had failed to reach the Allan Line had stipulated in her contract, and as a result John Brown & Company

John Brown and Company of Clydebank was a Scottish marine engineering and shipbuilding firm. It built many notable and world-famous ships including , , , , , and the ''Queen Elizabeth 2''.

At its height, from 1900 to the 1950s, it was one of ...

and Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson had suspended building of the much larger turbine ships and for Cunard Line

Cunard () is a British shipping and cruise line based at Carnival House at Southampton, England, operated by Carnival UK and owned by Carnival Corporation & plc. Since 2011, Cunard and its three ships have been registered in Hamilton, Berm ...

. However, there were conflicting reports as to whether ''Victorian''s initial failure was caused by a shortcoming of her turbines or the design of her hull.

On 16 January 1905, in an address to the Institute of Marine Engineers

An institute is an organisational body created for a certain purpose. They are often research organisations ( research institutes) created to do research on specific topics, or can also be a professional body.

In some countries, institutes ca ...

, Parsons confidently predicted that turbines would supersede reciprocating engines in ships of more than and more than 5,000 IHP, and would probably be adopted for ships above and .

On 16 March it was reported that ''Victorian'' had achieved on sea trials on the Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde is the mouth of the River Clyde. It is located on the west coast of Scotland and constitutes the deepest coastal waters in the British Isles (it is 164 metres deep at its deepest). The firth is sheltered from the Atlantic ...

, with her turbines developing some 12,000 shaft horsepower

Horsepower (hp) is a unit of measurement of power, or the rate at which work is done, usually in reference to the output of engines or motors. There are many different standards and types of horsepower. Two common definitions used today are the ...

and turning the screws at 260 RPM

Revolutions per minute (abbreviated rpm, RPM, rev/min, r/min, or with the notation min−1) is a unit of rotational speed or rotational frequency for rotating machines.

Standards

ISO 80000-3:2019 defines a unit of rotation as the dimensionl ...

. She entered service a week later, and before the end of the year had set an eastbound record of five days and five hours from Rimouski

Rimouski ( ) is a city in Quebec, Canada. Rimouski is located in the Bas-Saint-Laurent region, at the mouth of the Rimouski River. It has a population of 48,935 (as of 2021). Rimouski is the site of Université du Québec à Rimouski (UQAR), t ...

in Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

to Moville in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, which stood for some time.

Allan Line service

On 23 March 1905 ''Victorian'' began her maiden voyage fromLiverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

to Canada. Two days of bad weather prevented her from breaking any record, but she reached Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. The ...

via Moville at noon on 1 April after a crossing of seven days and 22 hours. A fortnight later, on 6 April, her sister ship ''Virginian'' joined her on the route. The pair were a commercial success, and after some adjustments to her machinery, they maintained a regular transatlantic service between Britain, Ireland and Canada until August 1914.

On 1 September 1905 ''Victorian'' was reported to have run aground at Cape St. Charles

Cape St. Charles is a headland on the coast of Labrador in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. At longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east– west position of a point on the surface of the ...

, Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

on an eastbound crossing, as dense smoke from forest fires had impaired navigation. She had of water in her number two hold, her 350 passengers were taken off to continue their journey on Allan Line's liner ''Bavarian'' a week later, and her mails were taken off and sent eastbound via New York.

On a westbound voyage on the morning of 11 August 1911, 57 of the stewards of ''Victorian''s first and second class dining saloons refused an instruction to help put ashore mail at Rimouski

Rimouski ( ) is a city in Quebec, Canada. Rimouski is located in the Bas-Saint-Laurent region, at the mouth of the Rimouski River. It has a population of 48,935 (as of 2021). Rimouski is the site of Université du Québec à Rimouski (UQAR), t ...

. The stewards later agreed to obey the instruction, but then refused to serve breakfast or lunch to the passengers. When ''Victorian'' reached Montreal that evening five Montreal Police

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple-p ...

vehicles met the ship and officers arrested all 57 stewards for mutiny. Allan Line suggested that the incident could be linked with the ongoing Liverpool transport strike that had begun on 14 June.

By 1912 ''Victorian'' was equipped for wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy or radiotelegraphy is transmission of text messages by radio waves, analogous to electrical telegraphy using cables. Before about 1910, the term ''wireless telegraphy'' was also used for other experimental technologies for ...

, operating on the 300 and 600 metre wavelengths. Her call sign

In broadcasting and radio communications, a call sign (also known as a call name or call letters—and historically as a call signal—or abbreviated as a call) is a unique identifier for a transmitter station. A call sign can be formally assigne ...

was MVN.

When RMS ''Titanic

RMS ''Titanic'' was a British passenger liner, operated by the White Star Line, which sank in the North Atlantic Ocean on 15 April 1912 after striking an iceberg during her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, United ...

'' sank on 15 April 1912 ''Victorian'' was about astern of her, travelling in the same direction. ''Victorian''s wireless operator received news of the sinking "from via ". The operator told ''Victorian''s Master

Master or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

* Ascended master, a term used in the Theosophical religious tradition to refer to spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans

*Grandmaster (chess), National Master ...

, Captain Outram, but her passengers were not told until she reached Halifax. Outram said that ''Victorian'' had to divert "very far south" to avoid icebergs, and that his lookouts saw a great field of ice and 13 icebergs at one time.

First World War

On 28 July 1914 the First World War began. TheBritish Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964, historically under its titular head, the Lord High Admiral – one of the Great Officers of State. For much of it ...

had been converting passenger liners into AMCs since shortly before the war, and on 6 August listed eight more to be requisitioned, including ''Victorian''. She was at Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

that day and was detained accordingly. But she seems to have been allowed to proceed to Liverpool in civilian service, as she was requisitioned on 17 August, and was commissioned at Chatham Dockyard

Chatham Dockyard was a Royal Navy Dockyard located on the River Medway in Kent. Established in Chatham in the mid-16th century, the dockyard subsequently expanded into neighbouring Gillingham (at its most extensive, in the early 20th century, ...

on 21 August. Initially her armament was eight 4.7-inch QF guns: two on her forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is the phrase " be ...

, two on her forward house, two on her after house and two on her poop deck

In naval architecture, a poop deck is a deck that forms the roof of a cabin built in the rear, or " aft", part of the superstructure of a ship.

The name originates from the French word for stern, ''la poupe'', from Latin ''puppis''. Thus ...

. Her pennant number

In the Royal Navy and other navies of Europe and the Commonwealth of Nations, ships are identified by pennant number (an internationalisation of ''pendant number'', which it was called before 1948). Historically, naval ships flew a flag that iden ...

was M 56.

''Victorian'' served with the 9th Cruiser Squadron from September 1914 until March 1915. In September 1914 she was ordered to the coast of

''Victorian'' served with the 9th Cruiser Squadron from September 1914 until March 1915. In September 1914 she was ordered to the coast of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

, which France had invaded in 1907 and forced to become a French protectorate in 1912. ''Victorian'' joined the off Cape Juby

Cape Juby (, trans. ''Raʾs Juby'', es, link=no, Cabo Juby) is a cape on the coast of southern Morocco, near the border with Western Sahara, directly east of the Canary Islands.

Its surrounding area, including the cities of Tarfaya and Tan-T ...

on 26 September, the two cruisers bombarded Moroccan villages the next day, and ''Victorian'' withdrew on 28 September.

From October 1914 until January 1915 ''Victorian'' patrolled near the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Morocc ...

. She called at Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and p ...

in Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierra ...

on 23–24 November. She patrolled the coast of Portugal in February, returned to home waters in March and was out of commission in April and May.

In June 1915 Cammell Laird

Cammell Laird is a British shipbuilding company. It was formed from the merger of Laird Brothers of Birkenhead and Johnson Cammell & Co of Sheffield at the turn of the twentieth century. The company also built railway rolling stock until 1929, ...

replaced ''Victorian''s forecastle guns with two six-pounder guns that had been removed from HMS ''Caribbean'', an RMSP liner that had briefly been an AMC but had then been deemed unsuitable. At about the same time ''Victorian''s other six 4.7-inch guns were replaced with six BL 6-inch and QF 6-inch naval gun

The QF 6-inch 40 calibre naval gun ( Quick-Firing) was used by many United Kingdom-built warships around the end of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century.

In UK service it was known as the QF 6-inch Mk I, II, III guns.Mk I, II and II ...

s. Also in June 1915 ''Victorian'' joined the 10th Cruiser Squadron

The 10th Cruiser Squadron, also known as Cruiser Force B was a formation of cruisers of the British Royal Navy from 1913 to 1917 and then again from 1940 to 1946.

First formation

The squadron was established in July 1913 and allocated to the T ...

.

With the 10th Cruiser Squadron ''Victorian'' was on the Northern Patrol

The Northern Patrol, also known as Cruiser Force B and the Northern Patrol Force, was an operation of the British Royal Navy during the First World War and Second World War. The Patrol was part of the British "distant" blockade of Germany. Its ma ...

from June 1915 until July 1917. Her patrols took her to the Norwegian Sea

The Norwegian Sea ( no, Norskehavet; is, Noregshaf; fo, Norskahavið) is a marginal sea, grouped with either the Atlantic Ocean or the Arctic Ocean, northwest of Norway between the North Sea and the Greenland Sea, adjoining the Barents Sea to ...

in 1915, around the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

and the northern part of the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

in 1916 and the same plus the Icelandic coast of the Denmark Strait

The Denmark Strait () or Greenland Strait ( , 'Greenland Sound') is an oceanic strait between Greenland to its northwest and Iceland to its southeast. The Norwegian island of Jan Mayen lies northeast of the strait.

Geography

The strait connect ...

in the first half of 1917.

In May 1916 the two six-pounders were removed from her forecastle and replaced with a pair of anti-aircraft guns. By October 1916 her armament also included depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon. It is intended to destroy a submarine by being dropped into the water nearby and detonating, subjecting the target to a powerful and destructive Shock factor, hydraulic shock. Most depth ...

s.

From August 1917 until November 1918 ''Victorian'' escorted convoys. In 1918 her pennant number was changed twice: to MI 91 in January and to MI 51 in April. From January 1918 she carried cargo and from April she carried troops, including US Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

and Australian Army

The Australian Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Royal Australian Air Force. The Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (Austral ...

.

On 4 November 1918 ''Victorian'' arrived in the River Mersey

The River Mersey () is in North West England. Its name derives from Old English and means "boundary river", possibly referring to its having been a border between the ancient kingdoms of Mercia and Northumbria. For centuries it has formed part ...

to be decommissioned from the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

. Her guns were removed on 27 November and her unused ammunition was unloaded on 27–29 November.

Canadian Pacific service

Canadian Pacific had taken over Allan Line in 1917. Cammell, Laird refitted ''Victorian'' for civilian service, and on 13 April 1920 she resumed her old route between Liverpool, Quebec and Montreal. In 1921 the UK government chartered ''Victorian'' as a troop ship toIndia

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. In 1922 the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company

The Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company, Limited was a Scottish shipbuilding company in the Govan area on the Clyde in Glasgow. Fairfields, as it is often known, was a major warship builder, turning out many vessels for the Royal Navy ...

converted her to oil-burning and replaced her original direct-drive turbines with new ones with single-reduction gearing, and Canadian Pacific renamed her ''Marloch''.

In the mid-1920s Canadian Pacific put ''Marloch'' in reserve, but she often saw service.

On 26 June 1925 ''Marloch'' was in the

In the mid-1920s Canadian Pacific put ''Marloch'' in reserve, but she often saw service.

On 26 June 1925 ''Marloch'' was in the Saint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connectin ...

at Quebec when the tug ''Ocean King'' approached to receive a hawser and tow her. ''Ocean King'' crossed ''Marloch''s bow too close and the liner rammed the tug. ''Ocean King'' capsized, the cold water of the river caused her boilers to explode, and all nine crew of the tug were killed.

On 3 February 1926 in fog in the Scheldt

The Scheldt (french: Escaut ; nl, Schelde ) is a river that flows through northern France, western Belgium, and the southwestern part of Netherlands, the Netherlands, with its mouth at the North Sea. Its name is derived from an adjective corr ...

off Vlissingen

Vlissingen (; zea, label=Zeelandic, Vlissienge), historically known in English as Flushing, is a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality and a city in the southwestern Netherlands on the former island of Walcheren. With its strategic l ...

, ''Marloch'' collided with the UK cargo ship

A cargo ship or freighter is a merchant ship that carries cargo, goods, and materials from one port to another. Thousands of cargo carriers ply the world's seas and oceans each year, handling the bulk of international trade. Cargo ships are usu ...

''Whimbrel'', which was holed on her starboard quarter and sank. ''Marloch'' was damaged and was towed to Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

for repair.

On 19 September 1928 ''Marloch'' was laid up at Southend-on-Sea

Southend-on-Sea (), commonly referred to as Southend (), is a coastal city and unitary authority area with borough status in southeastern Essex, England. It lies on the north side of the Thames Estuary, east of central London. It is bordered ...

. On 17 April 1929 Canadian Pacific sold her to Thos. W. Ward

Thos. W. Ward Ltd was a Sheffield, Yorkshire, steel, engineering and cement business, which began as coal and coke merchants. It expanded into recycling metal for Sheffield's steel industry, and then the supply and manufacture of machinery.

I ...

Ltd, who scrapped her at either Milford Haven

Milford Haven ( cy, Aberdaugleddau, meaning "mouth of the two Rivers Cleddau") is both a town and a community in Pembrokeshire, Wales. It is situated on the north side of the Milford Haven Waterway, an estuary forming a natural harbour that has ...

or Pembroke Dock.

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Victorian, RMS 1904 ships World War I Auxiliary cruisers of the Royal Navy Maritime incidents in 1925 Maritime incidents in 1926 Ocean liners of the United Kingdom Ships built in Belfast Steamships of the United Kingdom World War I cruisers of the United Kingdom