RMS Empress of Britain (1931) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

RMS ''Empress of Britain'' was a

Work began on ''Empress of Britain'' on 28 November 1928 when the plates of her keel were laid at John Brown & Co, Clydebank, Scotland.Turner, Gordon. (1992). ''Empress of Britain,'' p. 15. She was launched on 11 June 1930 by the

Work began on ''Empress of Britain'' on 28 November 1928 when the plates of her keel were laid at John Brown & Co, Clydebank, Scotland.Turner, Gordon. (1992). ''Empress of Britain,'' p. 15. She was launched on 11 June 1930 by the

''Empress of Britain'' made nine round-trips in 1931 between Southampton and Quebec, carrying 4,891 passengers westbound and 4,696 eastbound. To begin her winter cruise, she made a westbound trans-Atlantic trip to New York, carrying 378. On 3 December 1931, she sailed on a 128-day round-the-world cruise, to the Mediterranean, North Africa and the Holy Land, through the Suez Canal and into the Red Sea, then to India, Ceylon, Southeast Asia and the Dutch East Indies, on to China, Hong Kong and Japan, then across the Pacific to Hawaii and California before traversing the Panama Canal back to New York. The ship then made a one-way Atlantic crossing from New York to Southampton, where she entered dry dock for maintenance and reinstallation of her outer propellers. Until 1939, this schedule was duplicated with minor adjustments each year except 1933.

''Empress of Britain'' made nine round-trips in 1931 between Southampton and Quebec, carrying 4,891 passengers westbound and 4,696 eastbound. To begin her winter cruise, she made a westbound trans-Atlantic trip to New York, carrying 378. On 3 December 1931, she sailed on a 128-day round-the-world cruise, to the Mediterranean, North Africa and the Holy Land, through the Suez Canal and into the Red Sea, then to India, Ceylon, Southeast Asia and the Dutch East Indies, on to China, Hong Kong and Japan, then across the Pacific to Hawaii and California before traversing the Panama Canal back to New York. The ship then made a one-way Atlantic crossing from New York to Southampton, where she entered dry dock for maintenance and reinstallation of her outer propellers. Until 1939, this schedule was duplicated with minor adjustments each year except 1933.

Her captain from 1934 to 1937 was

Her captain from 1934 to 1937 was

The Argus newspaper Thursday 7 April 1938

In June 1939 ''Empress of Britain'' sailed from Halifax to Conception Bay, St Johns, Newfoundland and then eastbound to Southampton with her smallest passenger list. 40 passengers were on board: King George VI, Queen Elizabeth and 13 ladies and lords in waiting, 22 household staff, plus a photographer and two reporters. The royal couple and their entourage were comfortably settled in a string of suites. After this voyage, ''Empress of Britain'' returned to regular transatlantic service, but through summer 1939, war loomed. On 2 September 1939, one day before the United Kingdom declared war (seven days before Canada entered the war), ''Empress of Britain'' sailed on her last voyage for Canadian Pacific, with the largest passenger list in her history. Filled beyond capacity, and with temporary berths in the squash court and other spaces, ''Empress of Britain'' zig-zagged across the Atlantic, arriving in Quebec on 8 September 1939.

Upon arrival, the ship was repainted grey and then laid up awaiting orders. On 25 November 1939, ''Empress of Britain'' was requisitioned as a

Upon arrival, the ship was repainted grey and then laid up awaiting orders. On 25 November 1939, ''Empress of Britain'' was requisitioned as a

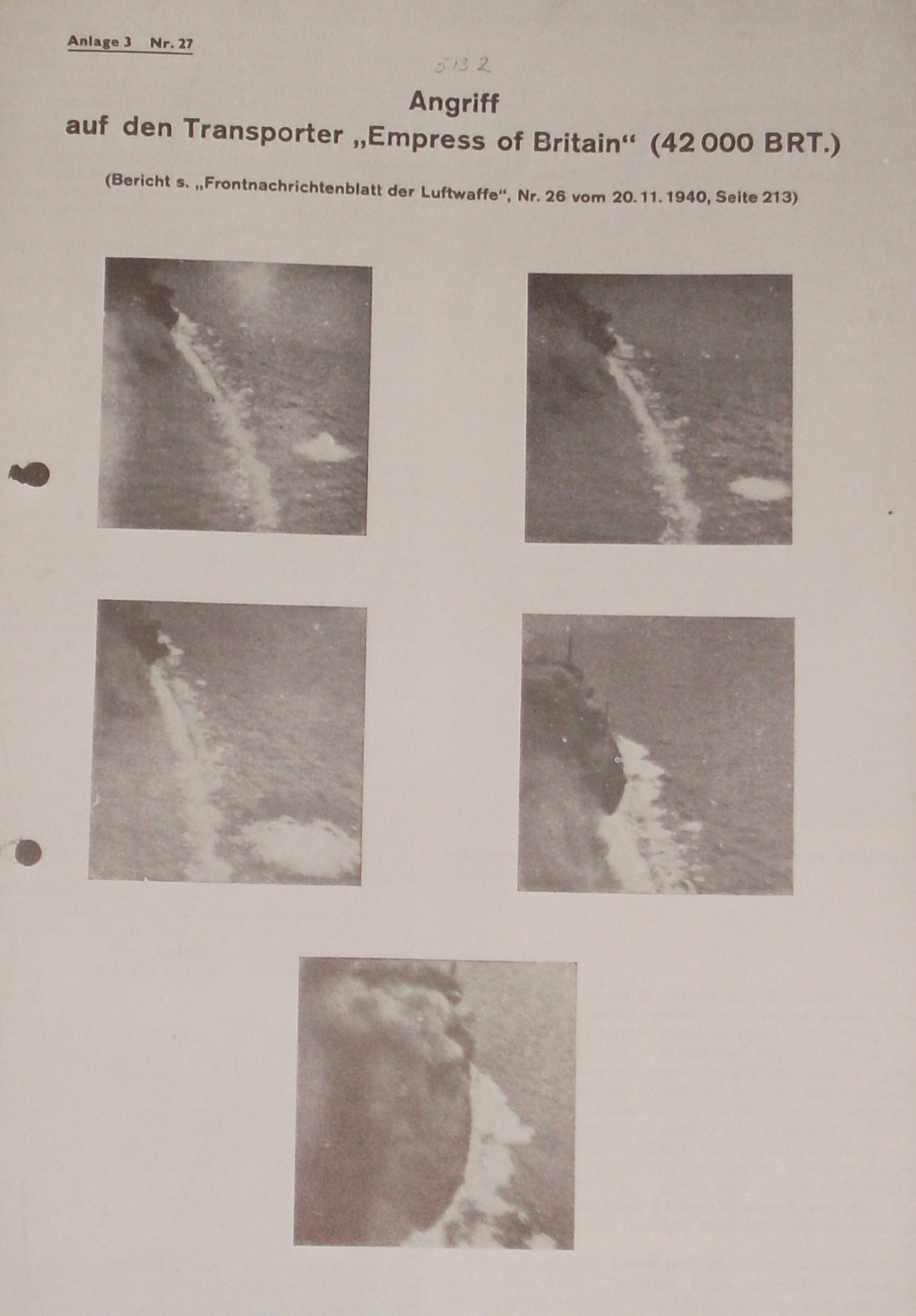

At around 9:20 am on 26 October 1940, travelling about 70 miles northwest of

At around 9:20 am on 26 October 1940, travelling about 70 miles northwest of

''Canadian Pacific Posters, 1883-1963.''

Montreal: Meridian Press. * Coleman, Terry. (1977)

''The Liners: A History of the North Atlantic Crossing.''

New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons.] ; * Harvey, Clive. (2004)

''RMS Empress Of Britain: Britain's Finest Liner.''

Stroud (England): Tempus Publishing.

OCLC 56462669

* McAuley, Rob and Miller, William. (1997)

''The Liners: A Voyage of Discovery.''

Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International Publishers & Wholesalers.

OCLC 38144342

* Miller, William H. (1985)

''The Fabulous Interiors of the Great Ocean Liners in Historic Photographs.''

New York:

OCLC 10697284

* __________. (1981)

''The Great Luxury Liners, 1927–1954: a Photographic Record.''

New York: Dover Publications. ; * Mitchell, WH and Sawyer, LA. (1967) ''Cruising Ships'' New York: Doubleday * Musk, George. (1981)

''Canadian Pacific: The Story of the Famous Shipping Line.''

Newton Abbot:

''Lost Treasure Ships of the Twentieth Century,''

Washington, D.C.:

OCLC 40964695

* Seamer, Robert. (1990)

''The Floating Inferno: The Story of the Loss of the Empress of Britain.''

Wellingborough: Stephens.

OCLC 59892514

* Turner, Gordon. (1992)

''Empress of Britain: Canadian Pacific's Greatest Ship.''

Toronto:

"Salvage team dives for £1bn wartime treasure,"

''

Information about ''Empress of Britain''

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20091010122038/http://www.oceanlinermuseum.co.uk/Empress%20of%20Britain%201930%20Photos.html www.oceanlinermuseum.co.uk: Launch of RMS ''Empress of Britain'', June 1930

IWM Interview with survivor Bertram Fryer

{{DEFAULTSORT:Empress of Britain (1931) 1930 ships Maritime incidents in October 1940 Ocean liners of the United Kingdom Ship fires Ships built on the River Clyde Ships of CP Ships Ships sunk by German submarines in World War II Shipwrecks of Ireland Steamships of the United Kingdom Troop ships of the United Kingdom World War II shipwrecks in the Atlantic Ocean

steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turbin ...

ocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).

Ca ...

built between 1928 and 1931 by John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

shipyard in Scotland, owned by the Canadian Pacific Railway

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadi ...

Company and operated by Canadian Pacific Steamship Company

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

. She was the second of three Canadian Pacific ships named ''Empress of Britain'', which provided scheduled trans-Atlantic passenger service from spring to autumn between Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

and Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

from 1931 until 1939.

In her time ''Empress of Britain'' was the largest, fastest and most luxurious ship between the United Kingdom and Canada, and the largest ship in the Canadian Pacific fleet. She was torpedoed on 28 October 1940 by and sank. At she was the largest liner lost in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

and the largest ship sunk by a U-boat.

Design and building

Work began on ''Empress of Britain'' on 28 November 1928 when the plates of her keel were laid at John Brown & Co, Clydebank, Scotland.Turner, Gordon. (1992). ''Empress of Britain,'' p. 15. She was launched on 11 June 1930 by the

Work began on ''Empress of Britain'' on 28 November 1928 when the plates of her keel were laid at John Brown & Co, Clydebank, Scotland.Turner, Gordon. (1992). ''Empress of Britain,'' p. 15. She was launched on 11 June 1930 by the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

. This was the first time that launching ceremonies in Britain were broadcast by radio to Canada and the United States.Miller, William H (1981). ''The Great Luxury Liners, 1927-1954,'' p. 41

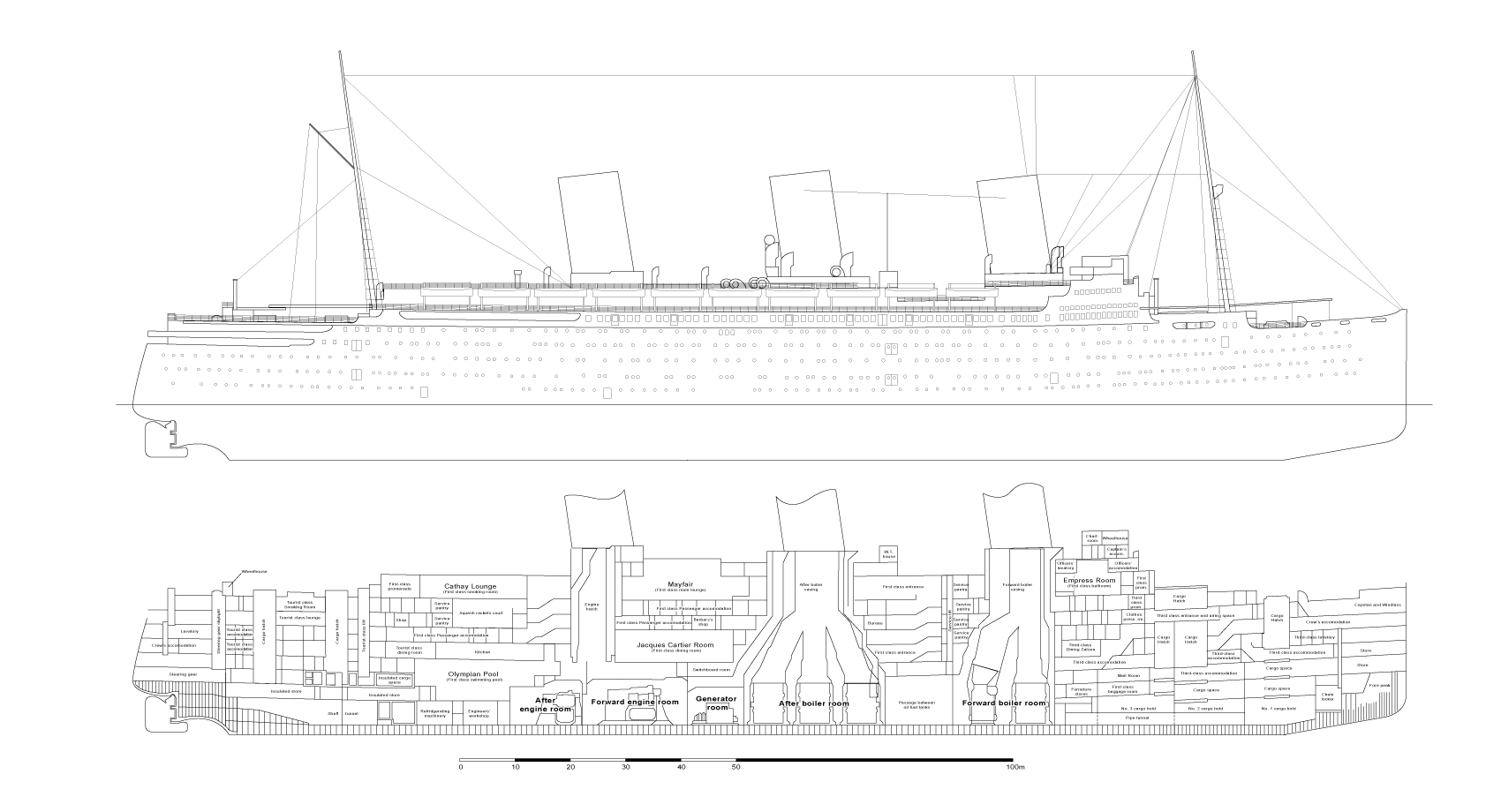

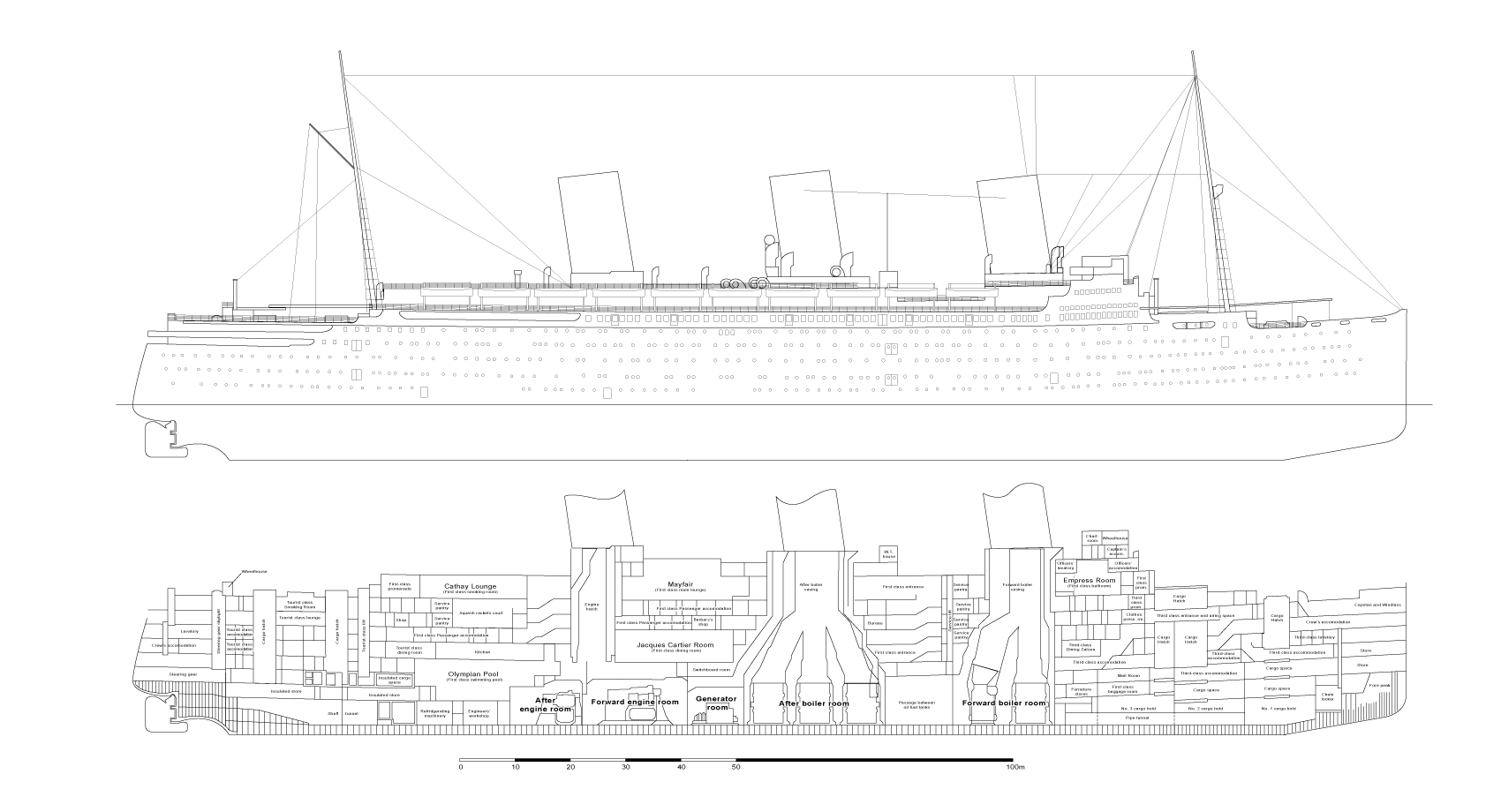

The ship had nine water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by the fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-gene ...

s with a combined heating surface of . Eight were Yarrow boiler

Yarrow boilers are an important class of high-pressure water-tube boilers. They were developed by

Yarrow & Co. (London), Shipbuilders and Engineers and were widely used on ships, particularly warships.

The Yarrow boiler design is characteristic ...

s, but as an experiment she was also the first to be fitted with a Johnson boiler The Johnson boiler is a water-tube boiler used for ship propulsion.

The Johnson design was developed by the British engineer J. Johnson in the late 1920s. A patent was granted in 1931, and one of these boilers was installed in the . This was a time ...

. Her boilers supplied steam at 425 lbf/in2 to 12 steam turbines, which drove her four propeller shafts by single reduction gearing and developed a combined power output of 12,753 NHP

Horsepower (hp) is a unit of measurement of power, or the rate at which work is done, usually in reference to the output of engines or motors. There are many different standards and types of horsepower. Two common definitions used today are the ...

.

''Empress of Britain''s UK official number

Official numbers are ship identifier numbers assigned to merchant ships by their flag state, country of registration. Each country developed its own official numbering system, some on a national and some on a port-by-port basis, and the formats hav ...

was 162582. Until 1933 her code letters

Code letters or ship's call sign (or callsign) Mtide Taurus - IMO 7626853"> SHIPSPOTTING.COM >> Mtide Taurus - IMO 7626853/ref> were a method of identifying ships before the introduction of modern navigation aids and today also. Later, with the i ...

were LHCB. Her call sign

In broadcasting and radio communications, a call sign (also known as a call name or call letters—and historically as a call signal—or abbreviated as a call) is a unique identifier for a transmitter station. A call sign can be formally assigne ...

was GMBJ.

The ship began sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s on 11 April 1931 where she recorded , and left Southampton on her maiden voyage to Quebec on 27 May 1931.

As the ship would sail a more northerly trans-Atlantic route where there was sometimes ice in the waters off Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, ''Empress of Britain'' was ordered with outer steel plating double the thickness at the stem and for back at either side, up to the waterline. Her sea trials showed her to be "the world's most economical steamship for fuel consumption per horsepower-hour

A horsepower-hour (symbol: hp⋅h) is an outdated unit of energy, not used in the International System of Units. The unit represents an amount of work a horse is supposed capable of delivering during an hour (1 horsepower

Horsepower (hp) is a u ...

for her day."Musk, p. 186.

Her primary role was to entice passengers between England and Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

instead of the more popular Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

–New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

route. The ship was designed to carry 1,195 passengers (465 first class, 260 tourist class and 470 third class).

She was the first passenger liner designed specifically to become a cruise ship in winter when the St. Lawrence River was frozen. ''Empress of Britain'' was annually converted into an all-first-class, luxury cruise ship

Cruise ships are large passenger ships used mainly for vacationing. Unlike ocean liners, which are used for transport, cruise ships typically embark on round-trip voyages to various ports-of-call, where passengers may go on tours known as "s ...

, carrying 700 passengers.

For the latter role her size was kept small enough to use the Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cos ...

and Suez canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

s, though at and , she was still large. When passing through Panama, there were only between the ship and the canal lock wall. She was powered by 12 steam turbines driving four propellers: the two inboard took two-thirds of the power, the outboard one-third. For cruising two engines were shut down and the two outboard propellers removed since speed was less important on a cruise. With four propellers, her speed during trials was , although her service speed was claimed to be , making her the fastest ship from England to Canada. Running on inner propellers, her speed was measured during trials at . The efficiency of this arrangement became clear in service – in transatlantic service, she consumed 356 tons of oil a day, while on her 1932 cruise, consumption fell to 179.

To serve as a beacon at night during emergencies her three funnels were illuminated by powerful floodlights. From the air the funnels could be spotted 50 miles away and ships could see the illuminated funnels at 30 miles distance.

Peacetime commercial service

After sea trials, the ship headed for Southampton to prepare for her maiden voyage to Quebec City. Canadian Pacific posters proclaimed the ship the "Five Day Atlantic Giantess", "Canada's Challenger" and "The World's Wondership". The night before her maiden voyage, thePrince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

decided to go to Southampton to bid bon voyage. His inspection of the ship caused a short delay but at 1:12pm on Wednesday, 27 May 1931 ''Empress of Britain'' left Southampton for Quebec. Once at sea, the Toronto newspaper ''The Globe'' ran an editorial on what the ship meant to Canadians.

“Canadian enterprise has issued a new challenge in the world of shipping by the completion and sailing of the Empress of Britain from England for Quebec. This giant Canadian Pacific liner of 42,500 tons sets a new standard for the Canadian route. Its luxurious equipment includes one entire deck for sport and recreation, another for public rooms, including a ballroom, with decorations by world-famous artists. There are apartments instead of cabins, and each is equipped with a radio receiving set for the entertainment of passengers. . . . In the later years of the last century, … there was long agitation for a ‘fast Atlantic service’. Time has brought the answer. Despite the current depression, Canada has a new ship which will reach far for traffic during the St. Lawrence season, and when winter comes will go on world cruises, carrying passengers who will ask and receive almost the last word in comfort and luxury in ocean travel. The first journey of the new Empress is a historic event in the record of Canadian advancement.”

''Empress of Britain'' made nine round-trips in 1931 between Southampton and Quebec, carrying 4,891 passengers westbound and 4,696 eastbound. To begin her winter cruise, she made a westbound trans-Atlantic trip to New York, carrying 378. On 3 December 1931, she sailed on a 128-day round-the-world cruise, to the Mediterranean, North Africa and the Holy Land, through the Suez Canal and into the Red Sea, then to India, Ceylon, Southeast Asia and the Dutch East Indies, on to China, Hong Kong and Japan, then across the Pacific to Hawaii and California before traversing the Panama Canal back to New York. The ship then made a one-way Atlantic crossing from New York to Southampton, where she entered dry dock for maintenance and reinstallation of her outer propellers. Until 1939, this schedule was duplicated with minor adjustments each year except 1933.

''Empress of Britain'' made nine round-trips in 1931 between Southampton and Quebec, carrying 4,891 passengers westbound and 4,696 eastbound. To begin her winter cruise, she made a westbound trans-Atlantic trip to New York, carrying 378. On 3 December 1931, she sailed on a 128-day round-the-world cruise, to the Mediterranean, North Africa and the Holy Land, through the Suez Canal and into the Red Sea, then to India, Ceylon, Southeast Asia and the Dutch East Indies, on to China, Hong Kong and Japan, then across the Pacific to Hawaii and California before traversing the Panama Canal back to New York. The ship then made a one-way Atlantic crossing from New York to Southampton, where she entered dry dock for maintenance and reinstallation of her outer propellers. Until 1939, this schedule was duplicated with minor adjustments each year except 1933.

Her captain from 1934 to 1937 was

Her captain from 1934 to 1937 was Ronald Niel Stuart

Ronald Niel Stuart, VC, DSO, RD, RNR (26 August 1886 – 8 February 1954) was a British Merchant Navy commodore and Royal Navy captain who was highly commended following extensive and distinguished service at sea over a period of more than ...

, VC, a First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

veteran entitled to fly the Blue Ensign

The Blue Ensign is a flag, one of several British ensigns, used by certain organisations or territories associated or formerly associated with the United Kingdom. It is used either plain or Defacement (flag), defaced with a Heraldic badge, ...

.

Canadian Pacific

The Canadian Pacific Railway (french: Chemin de fer Canadien Pacifique) , also known simply as CPR or Canadian Pacific and formerly as CP Rail (1968–1996), is a Canadian Class I railway incorporated in 1881. The railway is owned by Canadi ...

hoped to convince Midwesterners from Canada and the United States to travel by train to Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Communauté métrop ...

as opposed to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. This gave an extra day and a half of smooth sailing in the shorter, sheltered St Lawrence River transatlantic route, which Canadian Pacific advertised as "39 per cent less ocean". While initially successful, the novelty wore off, and ''Empress of Britain'' proved to be one of the least profitable liners from the 1930s.

Captain WG Busk-Wood was Master

Master or masters may refer to:

Ranks or titles

* Ascended master, a term used in the Theosophical religious tradition to refer to spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans

*Grandmaster (chess), National Master ...

of ''Empress of Britain'' when the ship visited Sydney from 2–4 April, and Melbourne on 6 April 1938. She was the largest liner to have visited Australia. A crowd of 250,000 turned out to welcome the liner in Melbourne and the event was reported iThe Argus newspaper Thursday 7 April 1938

In June 1939 ''Empress of Britain'' sailed from Halifax to Conception Bay, St Johns, Newfoundland and then eastbound to Southampton with her smallest passenger list. 40 passengers were on board: King George VI, Queen Elizabeth and 13 ladies and lords in waiting, 22 household staff, plus a photographer and two reporters. The royal couple and their entourage were comfortably settled in a string of suites. After this voyage, ''Empress of Britain'' returned to regular transatlantic service, but through summer 1939, war loomed. On 2 September 1939, one day before the United Kingdom declared war (seven days before Canada entered the war), ''Empress of Britain'' sailed on her last voyage for Canadian Pacific, with the largest passenger list in her history. Filled beyond capacity, and with temporary berths in the squash court and other spaces, ''Empress of Britain'' zig-zagged across the Atlantic, arriving in Quebec on 8 September 1939.

War service

Upon arrival, the ship was repainted grey and then laid up awaiting orders. On 25 November 1939, ''Empress of Britain'' was requisitioned as a

Upon arrival, the ship was repainted grey and then laid up awaiting orders. On 25 November 1939, ''Empress of Britain'' was requisitioned as a troop transport

A troopship (also troop ship or troop transport or trooper) is a ship used to carry soldiers, either in peacetime or wartime. Troopships were often drafted from commercial shipping fleets, and were unable land troops directly on shore, typicall ...

. First, she did four transatlantic trips taking troops from Canada to England. Then she was sent to Wellington, New Zealand, returning to Scotland in June 1940 as part of the "million dollar convoy" of seven luxury liners — , , ''Empress of Britain'', , , and .

In August 1940 ''Empress of Britain'' transported troops to Suez via Cape Town, returning with 224 military personnel and civilians, plus a crew of 419.

Sinking

Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

along the west coast, ''Empress of Britain'' was spotted by a German Focke-Wulf Fw 200

The Focke-Wulf Fw 200 ''Condor'', also known as ''Kurier'' to the Allies (English language, English: Courier), was a Nazi Germany, German all-metal four-engined monoplane originally developed by Focke-Wulf as a long-range airliner. A Japanese req ...

C ''Condor'' long-range bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching aerial torpedo, torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped ...

, commanded by Oberleutnant

() is the highest lieutenant officer rank in the German-speaking armed forces of Germany (Bundeswehr), the Austrian Armed Forces, and the Swiss Armed Forces.

Austria

Germany

In the German Army, it dates from the early 19th century. Trans ...

Bernhard Jope

Bernhard Jope (10 May 1914 – 31 July 1995) was a German bomber pilot during World War II. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves of Nazi Germany. As part of Kampfgeschwader 40 (bomber wing), Jope flew missio ...

. Jope's bomber strafed ''Empress of Britain'' three times and struck her twice with bomb

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the Exothermic process, exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-t ...

s.

Only after Jope returned to base in northern France was it discovered which ship he had attacked. A telex

The telex network is a station-to-station switched network of teleprinters similar to a Public switched telephone network, telephone network, using telegraph-grade connecting circuits for two-way text-based messages. Telex was a major method of ...

was sent to German Supreme Headquarters. Realising the significance, a reconnaissance plane went to verify; and the German news agency reported that ''Empress of Britain'' had been sunk:

:"The Empress of Britain was successfully attacked by German bombers on Saturday morning within the waters of Northern Ireland. The ship was badly hit and began to sink at once. The crew took to their boats."

Despite the ferocity of Jope's attack and the fires, there were few casualties. Bombs started a fire that began to overwhelm the ship. At 9:50am, Captain Sapworth gave the order to abandon ship. The fire was concentrated in the midsection, causing passengers to head for the bow and stern, and hampering launching of the lifeboat

Lifeboat may refer to:

Rescue vessels

* Lifeboat (shipboard), a small craft aboard a ship to allow for emergency escape

* Lifeboat (rescue), a boat designed for sea rescues

* Airborne lifeboat, an air-dropped boat used to save downed airmen

...

s. Most of the 416 crew, 2 gunners, and 205 passengers were picked up by the destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s and , and the anti-submarine trawler . A skeleton crew remained aboard.

The fire left the ship unable to move under her own power, but she was not sinking and the hull appeared intact despite a slight list. At 9:30am on 27 October, a party from went on board and attached tow ropes. The oceangoing tugs and had arrived and took the hulk under tow. Escorted by ''Broke'' and , and with cover from Short Sunderland

The Short S.25 Sunderland is a British flying boat patrol bomber, developed and constructed by Short Brothers for the Royal Air Force (RAF). The aircraft took its service name from the town (latterly, city) and port of Sunderland in North East ...

flying boats during daylight, the salvage convoy made for land at .

The , commanded by Hans Jenisch

Hans Jenisch (19 October 1913 – 29 April 1982) was a ''Kapitänleutnant'' in Nazi Germany's '' Kriegsmarine'' during the Second World War and a ''Kapitän zur See'' in West Germany's ''Bundesmarine''. He commanded a Type VIIA U-boat, sinking ...

, had been told and headed in that direction. He had to dive due to the flying boats, but that night, using hydrophones

A hydrophone ( grc, ὕδωρ + φωνή, , water + sound) is a microphone designed to be used underwater for recording or listening to underwater sound. Most hydrophones are based on a piezoelectric transducer that generates an electric potenti ...

(passive sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigation, navigate, measure distances (ranging), communicate with or detect o ...

), located the ships and closed in on them. The destroyers were zigzagging in escort; ''U-32'' placed herself between them and ''Empress of Britain'', from where she fired two torpedoes

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

. The first detonated prematurely; the second, however, hit, causing a massive explosion. Crews of the destroyers speculated this was caused by the fires aboard the liner reaching her fuel tanks. Jenisch manoeuvred ''U-32'' and fired a third torpedo, which hit the ship just aft of the earlier one. The ship began to fill with water and list heavily.

The tugs slipped the tow lines and at 2:05am on 28 October, ''Empress of Britain'' sank northwest of Bloody Foreland

Gweedore ( ; officially known by its Irish language name, ) is an Irish-speaking district and parish located on the Atlantic coast of County Donegal in the north-west of Ireland. Gweedore stretches some from Glasserchoo in the north to Crolly ...

, County Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ga, Contae Dhún na nGall) is a county of Ireland in the province of Ulster and in the Northern and Western Region. It is named after the town of Donegal in the south of the county. It has also been known as County Tyrconne ...

, Ireland at .

Gold and salvage

It was suspected that she had been carryinggold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile met ...

. The British Empire was shipping gold to North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

to improve its credit and pay its debt (bills for supplies). South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

was a gold producer, and ''Empress of Britain'' had recently berthed in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

. Most of the consignments of gold were transported from Cape Town to Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, and from there to America; there were not enough suitable ships and the gold was frequently held up in Sydney. It is possible that, as a result of this delay, ''Empress of Britain'' was taking gold from Cape Town to England, from where it could be moved across the Atlantic.

On 8 January 1949, the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' reported that a salvage attempt was to be made in the summer of that year. There were no follow-ups, and the story contained errors. In 1985, a potential salvager received a letter from the Department of Transport Shipping Policy Unit saying the gold on board had been recovered.

In 1995, salvagers found the ''Empress of Britain'' upside-down in of water. Using saturation diving

Saturation diving is diving for periods long enough to bring all tissues into equilibrium with the partial pressures of the inert components of the breathing gas used. It is a diving mode that reduces the number of decompressions divers working ...

, they found that the fire had destroyed most of the decks, leaving a largely empty shell rising from the sea floor. The bullion room, however, was still intact. Inside was a skeleton but no gold. It is suspected the gold was unloaded when the ''Empress of Britain'' was on fire and its passengers evacuated. The body inside the bullion room may have been that of someone involved in salvage.Pickford, p. 111

In popular culture

In 1990, Robert Seamer wrote ''The Floating Inferno: The Story of the Loss of the Empress of Britain''. He was on the ship when she was torpedoed and sunk. The 1989 novel ''The White Empress'' by Lyn Andrews is set on board ''Empress of Britain''. The 2018 novel ''Empress'' by Brian McPhee was inspired by the ship, and features a fictionalised account of the skeleton in the bullion room.See also

*Treasure hunting (marine)

Treasure hunter is the physical search for treasure. For example, treasure hunters try to find sunken shipwrecks and retrieve artifacts with market value. This industry is generally fueled by the market for antiquities. The practice of treasur ...

* CP Ships

CP Ships was a large Canadian shipping company established in the 19th century. From the late 1880s until after World War II, the company was Canada's largest operator of Atlantic and Pacific steamships. Many immigrants travelled on CP ships fr ...

References

Further reading

* Choco, Mark H, and Jones, David L. (1988)''Canadian Pacific Posters, 1883-1963.''

Montreal: Meridian Press. * Coleman, Terry. (1977)

''The Liners: A History of the North Atlantic Crossing.''

New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons.] ; * Harvey, Clive. (2004)

''RMS Empress Of Britain: Britain's Finest Liner.''

Stroud (England): Tempus Publishing.

OCLC 56462669

* McAuley, Rob and Miller, William. (1997)

''The Liners: A Voyage of Discovery.''

Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International Publishers & Wholesalers.

OCLC 38144342

* Miller, William H. (1985)

''The Fabulous Interiors of the Great Ocean Liners in Historic Photographs.''

New York:

Dover Publications

Dover Publications, also known as Dover Books, is an American book publisher founded in 1941 by Hayward and Blanche Cirker. It primarily reissues books that are out of print from their original publishers. These are often, but not always, books ...

. OCLC 10697284

* __________. (1981)

''The Great Luxury Liners, 1927–1954: a Photographic Record.''

New York: Dover Publications. ; * Mitchell, WH and Sawyer, LA. (1967) ''Cruising Ships'' New York: Doubleday * Musk, George. (1981)

''Canadian Pacific: The Story of the Famous Shipping Line.''

Newton Abbot:

David & Charles

David & Charles Ltd is an English publishing company. It is the owner of the David & Charles imprint, which specialises in craft and lifestyle publishing.

David and Charles Ltd acts as distributor for all David and Charles Ltd books and cont ...

.

* Pickford, Nigel. (1999)''Lost Treasure Ships of the Twentieth Century,''

Washington, D.C.:

National Geographic

''National Geographic'' (formerly the ''National Geographic Magazine'', sometimes branded as NAT GEO) is a popular American monthly magazine published by National Geographic Partners. Known for its photojournalism, it is one of the most widely ...

. OCLC 40964695

* Seamer, Robert. (1990)

''The Floating Inferno: The Story of the Loss of the Empress of Britain.''

Wellingborough: Stephens.

OCLC 59892514

* Turner, Gordon. (1992)

''Empress of Britain: Canadian Pacific's Greatest Ship.''

Toronto:

Stoddart Stoddart is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Alexander "Sandy" Stoddart (born 1959), Scottish sculptor

*Andrew Stoddart (1863–1915), English cricketer and rugby union player

* Cassie Jo Stoddart (1989-2006), American murder v ...

. .

* Watson-Smyth, Kate"Salvage team dives for £1bn wartime treasure,"

''

The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publis ...

'' (London). 9 November 1998.

External links

Information about ''Empress of Britain''

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20091010122038/http://www.oceanlinermuseum.co.uk/Empress%20of%20Britain%201930%20Photos.html www.oceanlinermuseum.co.uk: Launch of RMS ''Empress of Britain'', June 1930

IWM Interview with survivor Bertram Fryer

{{DEFAULTSORT:Empress of Britain (1931) 1930 ships Maritime incidents in October 1940 Ocean liners of the United Kingdom Ship fires Ships built on the River Clyde Ships of CP Ships Ships sunk by German submarines in World War II Shipwrecks of Ireland Steamships of the United Kingdom Troop ships of the United Kingdom World War II shipwrecks in the Atlantic Ocean