R. J. Mitchell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Reginald Joseph Mitchell (20 May 189511 June 1937) was a British

Reginald Joseph Mitchell was born on 20 May 1895 at 115 Congleton Road, Butt Lane, in Staffordshire, England. He was the second eldest of five children, and the eldest of three brothers. His father Herbert Mitchell was a

Reginald Joseph Mitchell was born on 20 May 1895 at 115 Congleton Road, Butt Lane, in Staffordshire, England. He was the second eldest of five children, and the eldest of three brothers. His father Herbert Mitchell was a

Between 1920 and 1936, Mitchell designed 24 aeroplanes. His early projects often involved adapting Supermarine's earlier aircraft; in June 1920 the Air Ministry announced a civilian aircraft competition, and Supermarine's entry for the competition was the Commercial Amphibian, an adaptation by Mitchell of the company's Supermarine Channel. The Amphibian finished second, but was judged the best of the three entrants in terms of design and reliability. His redesigned Supermarine Baby, renamed the

Between 1920 and 1936, Mitchell designed 24 aeroplanes. His early projects often involved adapting Supermarine's earlier aircraft; in June 1920 the Air Ministry announced a civilian aircraft competition, and Supermarine's entry for the competition was the Commercial Amphibian, an adaptation by Mitchell of the company's Supermarine Channel. The Amphibian finished second, but was judged the best of the three entrants in terms of design and reliability. His redesigned Supermarine Baby, renamed the  Supermarine's first design for a land aircraft, the

Supermarine's first design for a land aircraft, the

In February 1929, Mitchell submitted

In February 1929, Mitchell submitted

Even whilst the Sea Lion II was being modified at the

Even whilst the Sea Lion II was being modified at the

The Air Ministry, the

The Air Ministry, the

Interest in the competition waned after the 1927 race. There was no competition the following year, as the

Interest in the competition waned after the 1927 race. There was no competition the following year, as the

Britain's final entry in the series, the

Britain's final entry in the series, the

In 1930, specification F7/30 was issued for a fighter aircraft able to be used by both day and night squadrons. Mitchell's proposed design, the Type 224, was one of three monoplane designs made into prototypes for the Air Ministry. The final design incorporated an open cockpit, four

In 1930, specification F7/30 was issued for a fighter aircraft able to be used by both day and night squadrons. Mitchell's proposed design, the Type 224, was one of three monoplane designs made into prototypes for the Air Ministry. The final design incorporated an open cockpit, four

Whilst the Type 224 was still being built in 1933, Mitchell was proceeding with the design of the Type 300. This was to become his masterpiece, the

Whilst the Type 224 was still being built in 1933, Mitchell was proceeding with the design of the Type 300. This was to become his masterpiece, the

In 1933, Mitchell underwent a permanent

In 1933, Mitchell underwent a permanent

A bronze statue of Mitchell was unveiled in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, on 21 May 1995. The statue, by Colin Melbourne, was commissioned by

A bronze statue of Mitchell was unveiled in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, on 21 May 1995. The statue, by Colin Melbourne, was commissioned by

RJ Mitchell. A life in aviation.

from

Local Heroes: Reginald (RJ) Mitchell

from the

Spitfire legend

a 2005 interview with Gordon Mitchell about his father in the ''

A short clip of Mitchell

in the ''

aircraft designer

Aerospace engineering is the primary field of engineering concerned with the development of aircraft and spacecraft. It has two major and overlapping branches: aeronautical engineering and astronautical engineering. Avionics engineering is si ...

who worked for the Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

aviation company Supermarine

Supermarine was a British aircraft manufacturer that is most famous for producing the Spitfire fighter plane during World War II as well as a range of seaplanes and flying boats, and a series of jet-powered fighter aircraft after World War II. ...

from 1916 until 1936. He is best remembered for designing racing seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tec ...

s such as the Supermarine S.6B

The Supermarine S.6B is a British racing seaplane developed by R.J. Mitchell for the Supermarine company to take part in the Schneider Trophy competition of 1931. The S.6B marked the culmination of Mitchell's quest to "perfect the design of t ...

, and for leading the team that designed the Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Gri ...

.

Born in Butt Lane, Staffordshire, Mitchell attended Hanley High School and afterwards worked as an apprentice at a locomotive

A locomotive or engine is a rail transport vehicle that provides the motive power for a train. If a locomotive is capable of carrying a payload, it is usually rather referred to as a multiple unit, motor coach, railcar or power car; the us ...

engineering works, whilst also studying engineering and mathematics at night. In 1917 he moved to Southampton to join Supermarine. He was appointed Chief Engineer in 1920 and Technical Director in 1927. Between 1920 and 1936 he designed 24 aircraft, which included flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fuselag ...

s and racing seaplanes, light aircraft

A light aircraft is an aircraft that has a maximum gross takeoff weight of or less.Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third edition'', page 308. Aviation Supplies & Academics, 1997.

Light aircraft are used as utility aircraft c ...

, fighters

Fighter(s) or The Fighter(s) may refer to:

Combat and warfare

* Combatant, an individual legally entitled to engage in hostilities during an international armed conflict

* Fighter aircraft, a warplane designed to destroy or damage enemy warplanes ...

, and bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped from an aircr ...

s. From 1925 to 1929 he worked on a series of racing seaplanes, built by Supermarine to compete in the Schneider Trophy

The Coupe d'Aviation Maritime Jacques Schneider, also known as the Schneider Trophy, Schneider Prize or (incorrectly) the Schneider Cup is a trophy that was awarded annually (and later, biennially) to the winner of a race for seaplanes and flying ...

competition, the final entry in the series being the Supermarine S.6B. The S.6B won the trophy in 1931. Mitchell was authorised by Supermarine to proceed with a new design, the Type 300, which went on to become the Spitfire.

In 1933, Mitchell underwent surgery to treat rectal cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC), also known as bowel cancer, colon cancer, or rectal cancer, is the development of cancer from the colon or rectum (parts of the large intestine). Signs and symptoms may include blood in the stool, a change in bowel m ...

. He continued to work and earned his pilot's licence

Pilot licensing or certification refers to permits for operating aircraft. Flight crew licences are regulated by ICAO Annex 1 and issued by the civil aviation authority of each country. CAA’s have to establish that the holder has met a specifi ...

in 1934, but in early 1937, he was forced by a recurrence of the cancer to give up work. After his death that year, he was succeeded as chief designer at Supermarine by Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, he ...

.

Family and education

Reginald Joseph Mitchell was born on 20 May 1895 at 115 Congleton Road, Butt Lane, in Staffordshire, England. He was the second eldest of five children, and the eldest of three brothers. His father Herbert Mitchell was a

Reginald Joseph Mitchell was born on 20 May 1895 at 115 Congleton Road, Butt Lane, in Staffordshire, England. He was the second eldest of five children, and the eldest of three brothers. His father Herbert Mitchell was a Yorkshireman

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other English counties, functions have ...

who became headmaster of three Staffordshire schools in the Stoke-on-Trent

Stoke-on-Trent (often abbreviated to Stoke) is a city and unitary authority area in Staffordshire, England, with an area of . In 2019, the city had an estimated population of 256,375. It is the largest settlement in Staffordshire and is surrou ...

area, before he retired from teaching. He then helped to establish a printing

Printing is a process for mass reproducing text and images using a master form or template. The earliest non-paper products involving printing include cylinder seals and objects such as the Cyrus Cylinder and the Cylinders of Nabonidus. The e ...

business, Wood, Mitchell and C. Ltd, in Hanley

Hanley is one of the six towns that, along with Burslem, Longton, Fenton, Tunstall and Stoke-upon-Trent, amalgamated to form the City of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, England.

Hanley is the ''de facto'' city centre, having long been the ...

. Herbert Mitchell's wife Eliza Jane Brain was the daughter of a cooper

Cooper, Cooper's, Coopers and similar may refer to:

* Cooper (profession), a maker of wooden casks and other staved vessels

Arts and entertainment

* Cooper (producers), alias of Dutch producers Klubbheads

* Cooper (video game character), in ...

. When Reginald was a child, the family lived in Normacot

Normacot is an area of Longton, Stoke-on-Trent, in the county of Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire a ...

, now a suburb of Stoke-on-Trent.

Reginald (known to his family as "Reg") attended Queensberry Road Higher Elementary School from the age of eight, before moving on to Hanley High School. There he developed an interest in making and flying model aircraft

A model aircraft is a small unmanned aircraft. Many are replicas of real aircraft. Model aircraft are divided into two basic groups: flying and non-flying. Non-flying models are also termed static, display, or shelf models.

Aircraft manufactur ...

. In 1911, after leaving school at the age of 16, he worked as an apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

for Kerr Stuart & Co. of Fenton, a railway engineering

Railway engineering is a multi-faceted engineering discipline dealing with the design, construction and operation of all types of rail transport systems. It encompasses a wide range of engineering disciplines, including civil engineering, comput ...

works. After completing his apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

he worked in the drawing office at Kerr Stuart, whilst studying engineering and mathematics at a local technical college, where he displayed a talent for mathematics.

After leaving Kerr Stuart in 1916, Mitchell worked for a period as a part-time teacher. He applied to join the armed forces on two occasions, but was on each occasion rejected because of his training as an engineer.

Career at Supermarine

Early career and promotion

In 1916, Mitchell joined the Supermarine Aviation Works atSouthampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

, possibly for a probationary period

In a workplace setting, probation (or a probationary period) is a status given to new employees and trainees of a company, business, or organization. This status allows a supervisor, training official, or manager to evaluate the progress and s ...

. Since its formation in 1912, the company had specialised in building flying boats

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fuselag ...

, producing its first aircraft, the Pemberton-Billing P.B.1, in 1914. During the First World War, Supermarine was taken over by the British Government, and during this period the company produced the first British single-seat flying boat fighter, the Supermarine Baby.

On joining the company, Mitchell was given the opportunity to develop skills in a number of roles, so as to gain experience of the aircraft industry. His basic engineering training would have helped him to become established, as he adjusted from working with locomotives to understanding aeroplanes. A competent mathematician, Mitchell's ability to think creatively and use his intuition when looking at a design was soon recognised. The earliest record of his work at Supermarine is as a draughtsman, and dates from 1916. By 1917, he had become assistant to the company's owner and designer, Hubert Scott-Paine

Hubert Scott-Paine (11 March 1891 – 14 April 1954) was a British aircraft and boat designer, record-breaking power boat racer, entrepreneur, inventor, and sponsor of the winning entry in the 1922 Schneider Trophy.

Early life

Hubert Paine was ...

. He is likely to have played a role in the development of the Baby when in 1919 it was adapted for racing for the Schneider Trophy

The Coupe d'Aviation Maritime Jacques Schneider, also known as the Schneider Trophy, Schneider Prize or (incorrectly) the Schneider Cup is a trophy that was awarded annually (and later, biennially) to the winner of a race for seaplanes and flying ...

, and was renamed the Supermarine Sea Lion.

In 1918, Mitchell was promoted to become the works manager's assistant. When Supermarine’s chief designer William Hargreaves left the company in the summer of 1919, he was replaced by Mitchell, who took up his new duties later that year, leading a team that had in 1918 consisted of six draughtsmen and a secretary. Following his promotion, the 19-year-old returned to Staffordshire and married his fiancé Florence Dayson, an infant school headmistress, who was 11 years his senior. By 1921 he had become Supermarine's chief engineer. Following the departure of Scott-Paine in November 1923, Mitchell was able to negotiate a new contract, which led to greater influence in the company. The 10-year contract was a sign of his indispensability to Supermarine.

It is unclear how Mitchell came about to become so quickly promoted when he was still a young man, as few documents relating to his early career have survived. However, his early promotion was not usual at that time; other men of Mitchell's age held similar positions in other aircraft companies. Decades after his death, when approached for information about him, those surviving Supermarine colleagues who had known Mitchell were reluctant to recall their personal memories.

1920s civilian and military aircraft designs

Between 1920 and 1936, Mitchell designed 24 aeroplanes. His early projects often involved adapting Supermarine's earlier aircraft; in June 1920 the Air Ministry announced a civilian aircraft competition, and Supermarine's entry for the competition was the Commercial Amphibian, an adaptation by Mitchell of the company's Supermarine Channel. The Amphibian finished second, but was judged the best of the three entrants in terms of design and reliability. His redesigned Supermarine Baby, renamed the

Between 1920 and 1936, Mitchell designed 24 aeroplanes. His early projects often involved adapting Supermarine's earlier aircraft; in June 1920 the Air Ministry announced a civilian aircraft competition, and Supermarine's entry for the competition was the Commercial Amphibian, an adaptation by Mitchell of the company's Supermarine Channel. The Amphibian finished second, but was judged the best of the three entrants in terms of design and reliability. His redesigned Supermarine Baby, renamed the Supermarine Sea King

The Supermarine Sea King was a British single-seat amphibious biplane fighter designed by Supermarine in 1919. Developed from the Supermarine Baby and the Supermarine Sea Lion I, the Sea King was a single seater biplane powered by a pusher ...

, was exhibited the Olympia International Aero Exhibition in 1920, the first international exhibition to be held in the UK since the end of World War I. In 1922, the Chilean government bought a Channel, modified by Mitchell. That year he redesigned a version of the Commercial Amphibian, the Supermarine Sea Eagle

The Supermarine Sea Eagle was a British, passenger–carrying, amphibious flying boat. It was designed and built by the Supermarine Aviation Works for its subsidiary, the British Marine Air Navigation Co Ltd, to be used on their cross-channe ...

.

Mitchell produced new designs for aircraft early in his career; he designed the Supermarine Seal II in 1920, and the triplane

A triplane is a fixed-wing aircraft equipped with three vertically stacked wing planes. Tailplanes and canard foreplanes are not normally included in this count, although they occasionally are.

Design principles

The triplane arrangement may ...

Flying Boat Torpedo Carrier the following year. The historian Ralph Pegram notes that the unbuilt Torpedo Carrier reveals the "first true indication of Mitchell’s thoughts as a designer". In 1921 work began on the Supermarine Swan, a commercial carrier, but only the prototype was built. The Supermarine Seagull II—later used as the basis for future designs—began to receive production orders in 1922. The Amphibian Service Bomber was designed by Mitchell in 1924. Renamed the Supermarine Scarab

The Supermarine Sea Eagle was a British, passenger–carrying, amphibious flying boat. It was designed and built by the Supermarine Aviation Works for its subsidiary, the British Marine Air Navigation Co Ltd, to be used on their cross-channe ...

, 12 aircraft were bought by the Spanish Navy

The Spanish Navy or officially, the Armada, is the maritime branch of the Spanish Armed Forces and one of the oldest active naval forces in the world. The Spanish Navy was responsible for a number of major historic achievements in navigation, ...

; they remained in service until 1928.

Supermarine's first design for a land aircraft, the

Supermarine's first design for a land aircraft, the Supermarine Sparrow

The Supermarine Sparrow (later called the Sparrow I) was a British two-seat light biplane designed by R.J. Mitchell and built at Supermarine's works at Woolston, Southampton. It first flew on 11 September 1924. After being rebuilt in 1926 as ...

, competed unsuccessfully during the Air Ministry's Light Air Competition of 1924, and subsequently failed to gain orders. A variant, the Supermarine Sparrow II, was used by Mitchell to test his different airfoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is the cross-sectional shape of an object whose motion through a gas is capable of generating significant lift, such as a wing, a sail, or the blades of propeller, rotor, or turbine.

...

designs.

Work on the Supermarine Southampton

The Supermarine Southampton was a flying boat of the interwar period designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Supermarine. It was one of the most successful flying boats of the era.

The Southampton was derived from the experime ...

started in March 1924. It flew for the first time the following March, and entered service in July 1925. By the end of 1925, Mitchell's team had designed the Southampton II—the Southampton but with a metal hull. The plane, more powerful, lighter, and more durable than its predecessor, flew for the first time in 1927. A paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, rags, grasses or other vegetable sources in water, draining the water through fine mesh leaving the fibre evenly distributed ...

by Mitchell on the use of the Southampton appeared in the March 1926 edition of ''Flight

Flight or flying is the process by which an object moves through a space without contacting any planetary surface, either within an atmosphere (i.e. air flight or aviation) or through the vacuum of outer space (i.e. spaceflight). This can be ...

'' magazine. In 1928, a flight of Supermarine Southampton IIs left Felixstowe

Felixstowe ( ) is a port town in Suffolk, England. The estimated population in 2017 was 24,521. The Port of Felixstowe is the largest container port in the United Kingdom. Felixstowe is approximately 116km (72 miles) northeast of London.

Hi ...

on 14 October for Australia, and returned to the UK on 11 December. The expedition provided Mitchell's design team with valuable information about operating aircraft in the tropics

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

. The Southampton was one of the most successful flying boats of the between-war period, and established Britain as a leading developer of maritime aircraft. It was used to equip six RAF squadrons up to 1936.

In 1926, the Air Ministry issued specification 21/26 as a way to address the need for new fighter aircraft, and Mitchell's design team, which he had re-organised that year into separate drawing and technical offices, responded with a number of designs, including the Single Seat Fighter. By this time, Supermarine was moving away from wooden amphibious aircraft

An amphibious aircraft or amphibian is an aircraft (typically fixed-wing) that can take off and land on both solid ground and water, though amphibious helicopters do exist as well. Fixed-wing amphibious aircraft are seaplanes (flying boats ...

. The company concentrated instead on designing larger metal flying boats, such as the 3-Engined Biplane Flying Boat, designed in November 1927. The Supermarine Air Yacht

The Supermarine Air Yacht was a British luxury passenger-carrying flying boat. It was designed by Supermarine's chief designer R. J. Mitchell and built in Woolston, Southampton in 1929. It was commissioned by the brewing magnate Ernest Guinn ...

, and a new design, the Southampton X (not related to other planes with the same name), was ordered in June 1928. Mitchell dispensed with the complicated curved surfaces for the wings and the hulls of the Air Yacht and the Southampton X, and as a result these aircraft appeared "boxy".

Specification R.6/28, issued in 1928, resulted in a series of designs by Supermarine for a six-engined flying boat, with one of designs being a radical departure for Mitchell—it had a newly-designed cantilever wing

A cantilever is a rigid structural element that extends horizontally and is supported at only one end. Typically it extends from a flat vertical surface such as a wall, to which it must be firmly attached. Like other structural elements, a canti ...

with a large surface area and cross section. The aircraft was never built. From 1929 to 1931, he continued to design aircraft based on the Southampton and the Southampton X, such as the Supermarine Sea Hawk and its variant the Sea Hawk II, the Type 179, the Nanok and the Seamew.

New designs, production orders and patents (19291934)

In February 1929, Mitchell submitted

In February 1929, Mitchell submitted patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A p ...

GB 329411 A, "Improvements in the Cooling System of Engines for Automotive Vehicles", a condenser to be placed within the wings of an aircraft. The Air Ministry rejected Supermarine's proposal for such a wing-cooled aircraft, but in May 1929 a new specification allowed Mitchell to use his ideas again. A similar patent was submitted in 1931. The condenser was used in the Type 232, produced in April 1934, which was never put up for tender.

During the early 1930s, many of Mitchell's ideas never went past the early design stages. Attempts by the company to sell a 5-engined flying boat failed when a contract was cancelled in early 1932, leading to job losses and wage cuts at Supermarine. However in 1933 the company's fortunes were revived when it received an order for 12 Scarpas (previously the Southampton IV) under the specification R.19/33, the first contract for a new design by Mitchell since 1924. This order was followed by orders for the Supermarine Stranraer

The Supermarine Stranraer is a flying boat designed and built by the British Supermarine Aviation Works company at Woolston, Southampton. It was developed during the 1930s on behalf of its principal operator, the Royal Air Force (RAF). It w ...

, which went into production in 1937.

After the first Seagull V flew in June 1933, the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

showed an interest, and 24 planes were ordered. The same year the RAF made an initial order of 12 aircraft, now renamed the Supermarine Walrus

The Supermarine Walrus (originally designated the Supermarine Seagull V) was a British single-engine amphibious biplane reconnaissance aircraft designed by R. J. Mitchell and manufactured by Supermarine at Woolston, Southampton.

The Walrus f ...

. Following the issuance of Air Ministry specification 5/36, Mitchell worked on a redesigned version of the Walrus, which was given the name Sea Otter. Work on the Sea Otter was completed after Mitchell's death in 1937, and it first flew in September 1938.

In October 1934, Mitchell published an article in the ''Daily Mirror

The ''Daily Mirror'' is a British national daily tabloid. Founded in 1903, it is owned by parent company Reach plc. From 1985 to 1987, and from 1997 to 2002, the title on its masthead was simply ''The Mirror''. It had an average daily print ...

'', ‘What is happening now in Air Transport?’, in which he predicted that air transport would prove to be the safest form of transport.

Schneider trophy races (19221931)

Mitchell and his design team worked on a series of racing seaplanes, built to compete in the Schneider Trophy competition. His team included Alan Clifton (later head of the Technical Office), Arthur Shirvall, andJoseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, he ...

. These men were fundamental to Supermarine’s success, as was the National Physical Laboratory (NPL), which provided invaluable support, guidance and scientific expertise in the form of detailed reports. The competition helped to place Mitchell at the forefront of aviation design.

Sea Lion series (early 1920s)

Mitchell developed the Supermarine Sea King II to become the Sea Lion II, which competed for the 1922 Schneider Trophy inNaples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's admini ...

. The Sea Lion II won the race, flying at an average speed of .

There was not enough time for Supermarine to design a new flying boat for the 1923 competition, so the Sea Lion II was borrowed back from the Air Ministry to allow Mitchell to adapt it. He increased its maximum speed by , achieved with the assistance of D. Napier & Son, who supplied the Lion III engine. To reduce the effects of drag forces, Mitchell reduced the wingspan

The wingspan (or just span) of a bird or an airplane is the distance from one wingtip to the other wingtip. For example, the Boeing 777–200 has a wingspan of , and a wandering albatross (''Diomedea exulans'') caught in 1965 had a wingspan o ...

from , modified the strut

A strut is a structural component commonly found in engineering, aeronautics, architecture and anatomy. Struts generally work by resisting longitudinal compression, but they may also serve in tension.

Human anatomy

Part of the functionality o ...

s, float

Float may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music Albums

* ''Float'' (Aesop Rock album), 2000

* ''Float'' (Flogging Molly album), 2008

* ''Float'' (Styles P album), 2013

Songs

* "Float" (Tim and the Glory Boys song), 2022

* "Float", by Bush ...

s and hull, and changed the way the engines were fitted.

For the 1923 contest, two of the three British entrants were irreparably damaged before the race, leaving the Sea Lion III to compete alone. The United States team, flying Curtiss seaplanes, dominated the competition, with the winning pilot, David Rittenhouse

David Rittenhouse (April 8, 1732 – June 26, 1796) was an American astronomer, inventor, clockmaker, mathematician, surveyor, scientific instrument craftsman, and public official. Rittenhouse was a member of the American Philosophical Society ...

, managing to reach a top speed of .

Supermarine S.4 (1925)

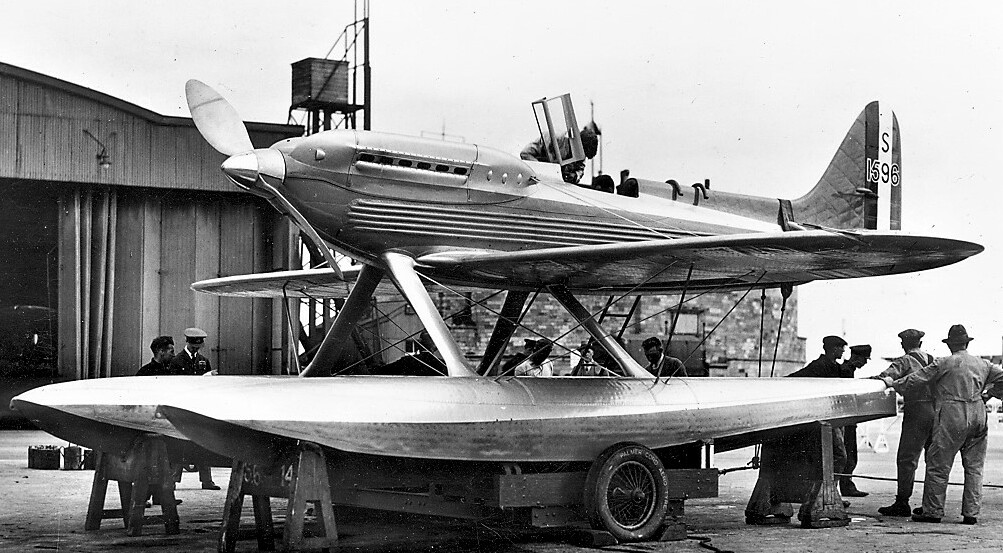

Even whilst the Sea Lion II was being modified at the

Even whilst the Sea Lion II was being modified at the Woolston

Woolston may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Woolston, Cheshire, a village and civil parish in Warrington

* Woolston, Devon, on the list of United Kingdom locations: Woof-Wy near Kingsbridge, Devon

* Woolston, Southampton, a city suburb in H ...

works, Mitchell was working on a new plane, as Supermarine knew the American monoplane was the best design then available. The Supermarine S.4

The Supermarine S.4 was a 1920s British single-engined monoplane built by Supermarine. Designed by a team led by the company's chief designer, R. J. Mitchell, it was built to race in the 1925 Schneider Trophy contest.

Mitchell's design ...

—the name was designated by Mitchell, with "S" standing for ''Schneider''—was a joint Napier/Supermarine venture. The Supermarine team was backed by the Air Ministry, and had greater freedom than was given by the US government to their designers. The S.4 was described after Mitchell's death as "his first outstanding success". He used the practical experience gained when he designed its successor, the Supermarine S.5.

Mitchell was fully aware of the need to reduce drag to increase speed. His new design for was a mid-wing, cantilever floatplane. It was comparable to a French monoplane, the Bernard SIMB V.2, which broken the flight airspeed record

An air speed record is the highest airspeed attained by an aircraft of a particular class. The rules for all official aviation records are defined by Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), which also ratifies any claims. Speed records ...

in December 1924. The S.4 lacked the newly-designed surface radiators, at that time still unavailable, but it was aerodynamic and aesthetically pleasing. Trial speeds reached and created a sensation in the press

Press may refer to:

Media

* Print media or news media, commonly called "the press"

* Printing press, commonly called "the press"

* Press (newspaper), a list of newspapers

* Press TV, an Iranian television network

People

* Press (surname), a fam ...

.

The S.4 crashed before the 1925 race, for reasons that were never clearly established. On the day of the navigation trials it stalled before falling flat into the sea from . When the pilot Louis Baird was rescued by a launch, Mitchell, who was on board the rescue launch, jokingly asked the injured man: "Is the water warm?"

1926 and 1927 competitions

The Air Ministry, the

The Air Ministry, the Society of British Aircraft Constructors

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Societ ...

and the Royal Aeronautical Society

The Royal Aeronautical Society, also known as the RAeS, is a British multi-disciplinary professional institution dedicated to the global aerospace community. Founded in 1866, it is the oldest aeronautical society in the world. Members, Fellows ...

(RAeS) decided against challenging for the Schneider Trophy in 1926, but Mitchell was able to confirm that Supermarine would be ready for the race. His work at the NPL started in November that year. From wind tunnel tests at the NPL he learned that the S.4’s radiator

Radiators are heat exchangers used to transfer thermal energy from one medium to another for the purpose of cooling and heating. The majority of radiators are constructed to function in cars, buildings, and electronics.

A radiator is always a ...

s had created a third of the aircraft’s total drag, and without this it would have been the most streamlined aircraft in the world. British aircraft companies intended to produce entries for the 1926 race, but the nature of the specifications issued by the Air Ministry meant that no aircraft could be completed and tested in time to be entered.

Two Supermarine S.5 seaplanes were entered for the 1927 contest, which was held in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

. Mitchell understood that a monoplane on twin floats produced lower drag than any other aircraft type of its day, and was convinced by wind tunnel tests at the NPL that the cantilever wing design was too heavy and should be abandoned. The NPL had demonstrated that flat-surfaced skin radiators reduced drag better than the corrugated variety preferred by American designers, so Mitchell used them to improve the S.5. He reduced the fuselage cross section area so that it was 35 per cent less than the area of the S.4—and complained about the RAF’s pilots being too large to fit into the resulting S.5's cockpit. The fuselage skin thickness was decreased by using duralumin

Duralumin (also called duraluminum, duraluminium, duralum, dural(l)ium, or dural) is a trade name for one of the earliest types of age-hardenable aluminium alloys. The term is a combination of ''Dürener'' and ''aluminium''.

Its use as a tra ...

.

Witnessed by the Italian dictator Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

, along with a huge crowd gathered along Venice's Lido

Lido may refer to:

Geography Africa

* Lido, a district in the city of Fez, Morocco

Asia

* Lido, an area in Chaoyang District, Beijing

* Lido, a cinema theater in Siam Square shopping area in Bangkok

* Lido City, a resort in West Java owned by M ...

, the two Supermarine S.5's alone finished the race, coming first and second. The third British entrant, a Gloster IV, along with the three Italian competitors flying Macchi M.52s, were forced to drop out of the race.

Mitchell had been elected to the RAeS in 1918. In 1927 he was awarded the society's Silver Medal. At the end of the year, he became the Technical Director at Supermarine. When the company was taken over by Vickers Ltd in 1928, he remained as Supermarine's chief designer—one of the conditions of the takeover was that he stay as a designer for the next five years.

Supermarine S.6 (1929)

Interest in the competition waned after the 1927 race. There was no competition the following year, as the

Interest in the competition waned after the 1927 race. There was no competition the following year, as the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale

The (; FAI; en, World Air Sports Federation) is the world governing body for air sports, and also stewards definitions regarding human spaceflight. It was founded on 14 October 1905, and is headquartered in Lausanne, Switzerland. It maintai ...

was persuaded by the Royal Aero Club

The Royal Aero Club (RAeC) is the national co-ordinating body for air sport in the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1901 as the Aero Club of Great Britain, being granted the title of the "Royal Aero Club" in 1910.

History

The Aero Club was fou ...

to hold races every two years in the future.

Mitchell was among those who could see a more powerful engine than the Napier Lion was required for any aircraft that competed in future contests. The Air Ministry invited Rolls-Royce Ltd

Rolls-Royce was a British luxury car and later an aero-engine manufacturing business established in 1904 in Manchester by the partnership of Charles Rolls and Henry Royce. Building on Royce's good reputation established with his cranes, they ...

to design a new engine specifically for Supermarine’s new seaplane, now designated the S.6. Rolls-Royce, under pressure to produce an engine in time and that matched S.6's streamlined shape, adopted the partially-developed Buzzard

Buzzard is the common name of several species of birds of prey.

''Buteo'' species

* Archer's buzzard (''Buteo archeri'')

* Augur buzzard (''Buteo augur'')

* Broad-winged hawk (''Buteo platypterus'')

* Common buzzard (''Buteo buteo'')

* Eastern b ...

. Mitchell in turn had to amend some of his design to accommodate the increase in total weight caused by introducing a larger engine, for instance by repositioning the forward float struts, and redesigning the engine cowling

A cowling is the removable covering of a vehicle's engine, most often found on automobiles, motorcycles, airplanes, and on outboard boat motors. On airplanes, cowlings are used to reduce drag and to cool the engine. On boats, cowlings are a cove ...

. The Air Ministry ordered two S.6 seaplanes, both of which were built by August 1929. Modifications to the seaplanes were made by Mitchell so the engines could be used at maximum power, as issues were discovered: the radiators were found to be inadequate; high engine torque

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational equivalent of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). It represents the capability of a force to produce change in the rotational motion of the ...

made the S.6 move in a circle; and the centre of gravity

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weighted relative position of the distributed mass sums to zero. This is the point to which a force may ...

was incorrectly positioned.

The 1929 race at Calshot

Calshot is a coastal village in Hampshire, England at the west corner of Southampton Water where it joins the Solent.OS Explorer Map, New Forest, Scale: 1:25 000.Publisher: Ordnance Survey B4 edition (2013).

History

In 1539, Henry VIII ordere ...

was won by Supermarine with the S.6 attaining an average speed of . Three of the four new aircraft were entered by the UK. The older Italian Macchi M.52R came second and Supermarine's backup, an S.5, took third place.

Supermarine S.6B (1931)

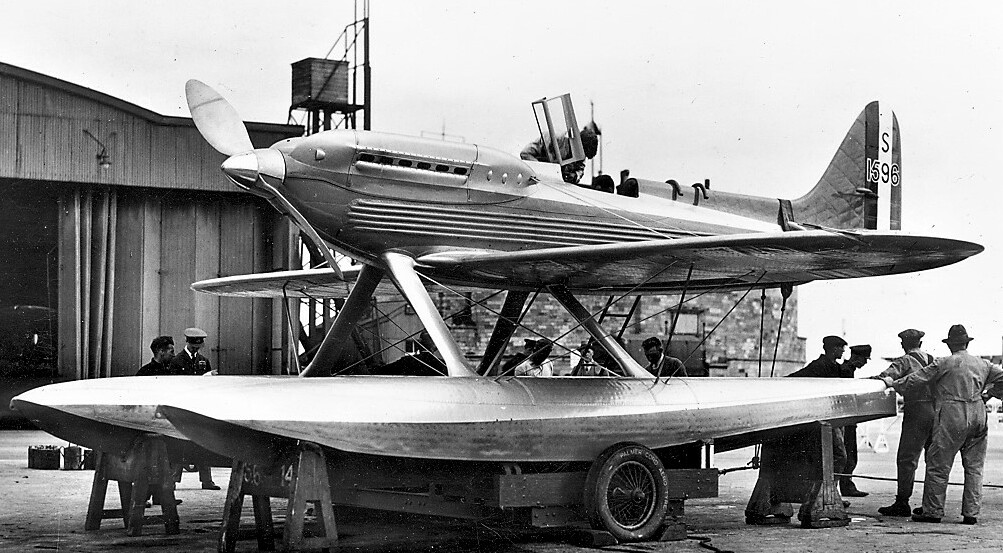

Britain's final entry in the series, the

Britain's final entry in the series, the Supermarine S.6B

The Supermarine S.6B is a British racing seaplane developed by R.J. Mitchell for the Supermarine company to take part in the Schneider Trophy competition of 1931. The S.6B marked the culmination of Mitchell's quest to "perfect the design of t ...

, marked the culmination of Mitchell's quest to "perfect the design of the racing seaplane". It was sponsored by a wealthy philanthropist

Philanthropy is a form of altruism that consists of "private initiatives, for the public good, focusing on quality of life". Philanthropy contrasts with business initiatives, which are private initiatives for private good, focusing on material ...

, Lady Houston

Dame Fanny Lucy Houston, Lady Houston, Baroness Byron ( Radmall; 8 April 1857 – 29 December 1936) was a British philanthropist, political activist and suffragist.

Beginning in 1933, she published the '' Saturday Review'', which was best kno ...

, who donated after the British Government decided not to enter an RAF team for the 1931 contest.

Mitchell opted to design an improved version of the S.6, whilst making as few changes as possible. The improvements that were made included a more powerful engine, and provision was made for such effects as the increase in engine-produced heat and extra torque, and the greater quantities of cooling oil and fuel required. The S.6B was a larger seaplane than the S.6, and had to be given a more efficient cooling system, and a stronger frame.

The S.6B competed the course successfully, and won the 1931 race. As the Schneider Trophy rules included the stipulation that the contest would end when any one country managed to win the trophy three times in five years, the S.6B's victory won the contest outright for Britain. The aircraft went on to break the world air speed record when it reached a speed of that year. Mitchell was awarded the Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE) on 29 December 1931 for services in connection with the Schneider Trophy contest.

Type 224

In 1930, specification F7/30 was issued for a fighter aircraft able to be used by both day and night squadrons. Mitchell's proposed design, the Type 224, was one of three monoplane designs made into prototypes for the Air Ministry. The final design incorporated an open cockpit, four

In 1930, specification F7/30 was issued for a fighter aircraft able to be used by both day and night squadrons. Mitchell's proposed design, the Type 224, was one of three monoplane designs made into prototypes for the Air Ministry. The final design incorporated an open cockpit, four Vickers machine gun

The Vickers machine gun or Vickers gun is a water-cooled .303 British (7.7 mm) machine gun produced by Vickers Limited, originally for the British Army. The gun was operated by a three-man crew but typically required more men to move and o ...

s, and a Rolls-Royce Goshawk

The Rolls-Royce Goshawk was a development of the Rolls-Royce Kestrel

The Kestrel or type F is a 21 litre (1,300 in³) 700 horsepower (520 kW) class V-12 aircraft engine from Rolls-Royce, their first cast-block engine and the pattern ...

engine, along with a fixed undercarriage. Also included was an inverted gull wing, needed due to the demands of the engine's cooling system. The wing lacked flaps, a requirement for the aircraft to land at safe speeds.

Unofficially named the Spitfire, the Type 224 first flew on February 1934. The aircraft looked clumsy, and was inefficient, in part because the cooling system failed to prevent the engine from overheating. The RAF decided that the Type 224's performance was unsatisfactory, and selected the Gloster Gladiator

The Gloster Gladiator is a British biplane fighter. It was used by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) (as the Sea Gladiator variant) and was exported to a number of other air forces during the late 1930s.

Developed private ...

in preference.

Supermarine Spitfire

Whilst the Type 224 was still being built in 1933, Mitchell was proceeding with the design of the Type 300. This was to become his masterpiece, the

Whilst the Type 224 was still being built in 1933, Mitchell was proceeding with the design of the Type 300. This was to become his masterpiece, the Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Gri ...

. He cleaned up the design of the Type 224, using the same engine but incorporating a shorter wing and a retractable undercarriage. The Air Ministry rejected Mitchell's design, but he modified it, for instance by making the wing thinner and shorter, by including the newly-designed Rolls-Royce Merlin

The Rolls-Royce Merlin is a British liquid-cooled V-12 piston aero engine of 27-litres (1,650 cu in) capacity. Rolls-Royce designed the engine and first ran it in 1933 as a private venture. Initially known as the PV-12, it was later ...

engine, and by making use of an innovative new cooling system—the latter being an example of his willingness to accept ideas from other people.

For a short period, design work continued using private funding, but in December 1934 the Air Ministry contracted Supermarine to construct a prototype that was based on Mitchell's design. Mitchell objected to the Air Ministry's insistence that the Spitfire be modified to have a tail wheel

Conventional landing gear, or tailwheel-type landing gear, is an aircraft undercarriage consisting of two main wheels forward of the center of gravity and a small wheel or skid to support the tail.Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of Aeronautical Term ...

. At the time he was not told that, in preparation for a future war, the government had decided to build hard surface runways for the RAF, a decision that meant the modification to the Spitfire was necessary.

The prototype, given the serial ''K5054'', first flew on 6 March 1936, at Eastleigh

Eastleigh is a town in Hampshire, England, between Southampton and Winchester. It is the largest town and the administrative seat of the Borough of Eastleigh, with a population of 24,011 at the 2011 census.

The town lies on the River Itchen, o ...

, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English cities on its south coast, Southampton and Portsmouth, Hampshire is ...

. Mitchell witnessed the flight. Despite being ill, he travelled to Eastleigh during the flight tests for ''K5054''. In June 1936, before the prototype had completed being trialled, the Air Ministry placed an order for 310 Spitfires.

Many of the technical advances in the Spitfire were made by people other than Mitchell: the thin elliptical wings were designed by the Canadian aerodynamicist

Aerodynamics, from grc, ἀήρ ''aero'' (air) + grc, δυναμική (dynamics), is the study of the motion of air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dyn ...

Beverley Shenstone

Beverley Strahan Shenstone MASc, HonFRAes, FAIAA, AFIAS, FCAISI, HonOSTIV (10 June 1906 – 9 November 1979) was a Canadian aerodynamicist often credited with developing the aerodynamics of the Supermarine Spitfire elliptical wing. In his lat ...

, and the Spitfire shared similarities with the Heinkel He 70

The Heinkel He 70 ''Blitz'' ("lightning") was a German mail plane and fast passenger monoplane aircraft of the 1930s designed by Heinkel Flugzeugwerke, which was later used as a bomber and for aerial reconnaissance. It had a brief commercial ca ...

Blitz. The under-wing radiators had been designed by the Royal Aircraft Establishment

The Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) was a British research establishment, known by several different names during its history, that eventually came under the aegis of the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD), before finally losing its identity in mer ...

, and monocoque

Monocoque ( ), also called structural skin, is a structural system in which loads are supported by an object's external skin, in a manner similar to an egg shell. The word ''monocoque'' is a French term for "single shell".

First used for boats, ...

construction had been first developed in the United States. Mitchell's achievement lay in the merger of these different influences into a single design, originating from his "unparalleled expertise in high-speed flight... and a brilliant practical engineering ability, exemplified in this instance by the incorporation of vital lessons learned from Supermarine's unsuccessful type 224 fighter". The quality of the design enabled the Spitfire to be continually improved throughout World War II.

Illness and final years

In 1933, Mitchell underwent a permanent

In 1933, Mitchell underwent a permanent colostomy

A colostomy is an opening (stoma) in the large intestine (colon), or the surgical procedure that creates one. The opening is formed by drawing the healthy end of the colon through an incision in the anterior abdominal wall and suturing it into ...

to treat rectal cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC), also known as bowel cancer, colon cancer, or rectal cancer, is the development of cancer from the colon or rectum (parts of the large intestine). Signs and symptoms may include blood in the stool, a change in bowel m ...

, which left him permanently disabled. Despite this, he continued to work on the Spitfire and a four-engined bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped from an aircr ...

, the Type 317. Unusually for an aircraft designer in those days, he took flying lessons. He obtained his pilot's licence

Pilot licensing or certification refers to permits for operating aircraft. Flight crew licences are regulated by ICAO Annex 1 and issued by the civil aviation authority of each country. CAA’s have to establish that the holder has met a specifi ...

and made his first solo flight in July 1934.

In 1936 Mitchell was diagnosed again with cancer, and early the following year was forced by his illness to give up work. In his absence, his assistant Harold led the design team at Supermarine. Mitchell flew to Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

for specialist treatment, and remained there for a month, but returned home after the treatment proved to be ineffective. He died at home in Portswood

Portswood is a suburb and Electoral Ward of Southampton, England. The suburb lies to the north-north-east of the city centre and is bounded by (clockwise from west) Freemantle, Highfield, Swaythling, St. Denys and Bevois Valley.

Portswood ...

, Southampton, on 11 June 1937 at the age of 42.

The quality of the flying boats designed by Mitchell for the RAF established him as the foremost aircraft designer in Britain. His obituary

An obituary ( obit for short) is an article about a recently deceased person. Newspapers often publish obituaries as news articles. Although obituaries tend to focus on positive aspects of the subject's life, this is not always the case. Ac ...

published in ''The Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society'' in 1937 described him as "brilliant" and "one of the leading designers in the world". The Society paid tribute to their colleague, describing him as being "a quiet, subtle, not obvious genius" who had "an intuitive capacity for grasping the essentials, getting to the point and staying there". Smith, became Chief Designer at Supermarine after Mitchell's death, said of him that "He was an inveterate drawer on drawings, particularly general arrangements,... hich wereusually accepted when the thing was redrawn."

Posthumous recognition

Mitchell's career was dramatised in the British 1942 film ''The First of the Few

''The First of the Few'' (US title ''Spitfire'') is a 1942 British black-and-white biographical film produced and directed by Leslie Howard, who stars as R. J. Mitchell, the designer of the Supermarine Spitfire fighter aircraft. David Niven co ...

''. He was portrayed by Leslie Howard

Leslie Howard Steiner (3 April 18931 June 1943) was an English actor, director and producer.Obituary ''Variety'', 9 June 1943. He wrote many stories and articles for ''The New York Times'', ''The New Yorker'', and '' Vanity Fair'' and was one ...

, who also produced and directed the film.

The Mitchell Memorial Youth Theatre, now known as Mitchell Arts Centre, was opened in Stoke-on-Trent in 1957 after was raised by public subscription

Subscription refers to the process of investors signing up and committing to invest in a financial instrument, before the actual closing of the purchase. The term comes from the Latin word ''subscribere''.

Historical Praenumeration

An early form ...

. Butt Lane Junior School, was renamed as the Reginald Mitchell County Primary School in 1959, and Hanley High School was renamed Mitchell High School in 1989. The R J Mitchell Primary School at Hornchurch

Hornchurch is a suburban town in East London, England, and part of the London Borough of Havering. It is located east-northeast of Charing Cross. It comprises a number of shopping streets and a large residential area. It historically formed a ...

, originally named the Mitchell Junior School when it opened on 2 December 1968, is also named in his honour. Supermarine Spitfires piloted by Commonwealth and European airmen flew from RAF Hornchurch

Royal Air Force Hornchurch or RAF Hornchurch is a former Royal Air Force sector station in the parish of Hornchurch, Essex (now the London Borough of Havering in Greater London), located to the southeast of Romford. The airfield was known as Sut ...

.

In 1986 Mitchell was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame

The International Air & Space Hall of Fame is an honor roll of people, groups, organizations, or things that have contributed significantly to the advancement of aerospace flight and technology, sponsored by the San Diego Air & Space Museum. Sin ...

at the San Diego Air & Space Museum

San Diego Air & Space Museum (SDASM, formerly the San Diego Aerospace Museum) is an aviation and space exploration museum in San Diego, California, United States. The museum is located in Balboa Park and is housed in the former Ford Building, ...

. The American philanthropist Sidney Frank

Sidney E. Frank (October 2, 1919 – January 10, 2006) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He became a billionaire through his promotion of Grey Goose vodka and Jägermeister.

Early life, family, education

Frank was born to a Jewish ...

unveiled a statue of Mitchell at the Science Museum, London

The Science Museum is a major museum on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, London. It was founded in 1857 and is one of the city's major tourist attractions, attracting 3.3 million visitors annually in 2019.

Like other publicly funded ...

in 2005. The slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

drawing board's surface depicts the drawing of the prototype Spitfire from June 1936. The stone sculpture was created by Stephen Kettle

Stephen Kettle (born 12 July 1966, in Castle Bromwich, Warwickshire, England) is a British sculptor who works exclusively with slate.

Career

Kettle is a self-taught sculptor with no formal training. His best known works include Supermari ...

and given to the museum by the Sidney E. Frank Foundation.

There are plaques dedicated to Mitchell at his Southampton home, and his birthplace in Butt Lane. Papers relating to his work at Supermarine are preserved at the archives of the Royal Air Force Museum London

The Royal Air Force Museum London (also commonly known as the RAF Museum) is located on the former Hendon Aerodrome. It includes five buildings and hangars showing the history of aviation and the Royal Air Force. It is part of the Royal Air Fo ...

.

A bronze statue of Mitchell was unveiled in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, on 21 May 1995. The statue, by Colin Melbourne, was commissioned by

A bronze statue of Mitchell was unveiled in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, on 21 May 1995. The statue, by Colin Melbourne, was commissioned by Stoke-on-Trent City Council

Stoke-on-Trent City Council is the local authority of Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, England. As a unitary authority, it has the combined powers of a non-metropolitan county and district council and is administratively separate from the rest of ...

, and stands outside The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery. The statue depicts Mitchell wearing a suit, holding a pen in his right hand and a book in his left.

The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery, in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, is home to a Spitfire RW388, which was donated to Stoke-on-Trent in 1972 by the RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

, to honour the city’s connection Reginald Mitchell.

Southampton City Art Gallery

The Southampton City Art Gallery is an art gallery in Southampton, southern England. It is located in the Civic Centre on Commercial Road.

The gallery opened in 1939 with much of the initial funding from the gallery coming from two bequests, o ...

holds an oil painting of Mitchell, painted in 1942 by Frank Ernest Beresford.

Personality

Mitchell was by nature a reserved and modest man. He was a reticent public speaker who disliked presenting papers. According to one member of his department, "he said nothing unless there was something worth saying". He avoided publicity, and was not widely known to the general public until after his death. According to his son Gordon, Mitchell was resentful of authority being imposed on him or of the routines of the workplace, and was short-tempered and "a difficult man to live with sometimes". Often given full scope at Supermarine, he was a strict taskmaster who nevertheless struggled with the level of organisation needed for a company such as Supermarine. When the engineerBarnes Wallis

Sir Barnes Neville Wallis (26 September 1887 – 30 October 1979) was an English engineer and inventor. He is best known for inventing the bouncing bomb used by the Royal Air Force in Operation Chastise (the "Dambusters" raid) to attack ...

was employed to improve the efficiency of Mitchell's department in 1930, Wallis had to be recalled after their personalities clashed. The ''ODNB'' describes Mitchell as being highly gifted and intelligent, but someone who was "often stern and irascible towards those less gifted than himself". He was devoted to his staff at Supermarine, to whom he showed kindness and humanity, and they in turn repaid him with loyalty and affection.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

RJ Mitchell. A life in aviation.

from

Solent Sky

Solent Sky is an aviation museum in Southampton, Hampshire, previously known as Southampton Hall of Aviation.

It depicts the history of aviation in Southampton, the Solent area and Hampshire. There is special focus on the Supermarine aircraft ...

Local Heroes: Reginald (RJ) Mitchell

from the

BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

Spitfire legend

a 2005 interview with Gordon Mitchell about his father in the ''

Southern Daily Echo

The ''Southern Daily Echo'', more commonly known as the ''Daily Echo'' or simply ''The Echo'', is a regional tabloid newspaper based in Southampton, covering the county of Hampshire in the United Kingdom. The newspaper is owned by Newsquest, on ...

''

A short clip of Mitchell

in the ''

Equinox

A solar equinox is a moment in time when the Sun crosses the Earth's equator, which is to say, appears directly above the equator, rather than north or south of the equator. On the day of the equinox, the Sun appears to rise "due east" and set ...

'' episode 'Spitfire', shown in the United Kingdom on Channel 4

Channel 4 is a British free-to-air public broadcast television network operated by the state-owned Channel Four Television Corporation. It began its transmission on 2 November 1982 and was established to provide a fourth television service in ...

on 9 September 1990 (the clip is at 17' 52")

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mitchell, R. J.

1895 births

1937 deaths

Aircraft designers

Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

English aerospace engineers

Fellows of the Royal Aeronautical Society

People from Butt Lane

Engineers from Southampton

Supermarine Spitfire