Quit India Movement on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Quit India Movement, also known as the August Kranti Movement, was a movement launched at the Bombay session of the All India Congress Committee by

The Quit India Movement, also known as the August Kranti Movement, was a movement launched at the Bombay session of the All India Congress Committee by

Several political groups active during the

Several political groups active during the

According to John F. Riddick, from 9 August 1942 to 21 September 1942, the Quit India Movement:

:attacked 550 post offices, 250 railway stations, damaged many rail lines, destroyed 70 police stations, and burned or damaged 85 other government buildings. There were about 2,500 instances of telegraph wires being cut. The greatest level of violence occurred in Bihar. The Government of India deployed 57 battalions of British troops to restore order.

At the national level the lack of leadership meant the ability to galvanise rebellion was limited. The movement had a local impact in some areas. especially at Satara in Maharashtra, Talcher in Odisha, and Midnapore. In Tamluk and

According to John F. Riddick, from 9 August 1942 to 21 September 1942, the Quit India Movement:

:attacked 550 post offices, 250 railway stations, damaged many rail lines, destroyed 70 police stations, and burned or damaged 85 other government buildings. There were about 2,500 instances of telegraph wires being cut. The greatest level of violence occurred in Bihar. The Government of India deployed 57 battalions of British troops to restore order.

At the national level the lack of leadership meant the ability to galvanise rebellion was limited. The movement had a local impact in some areas. especially at Satara in Maharashtra, Talcher in Odisha, and Midnapore. In Tamluk and

The Quit India Movement, also known as the August Kranti Movement, was a movement launched at the Bombay session of the All India Congress Committee by

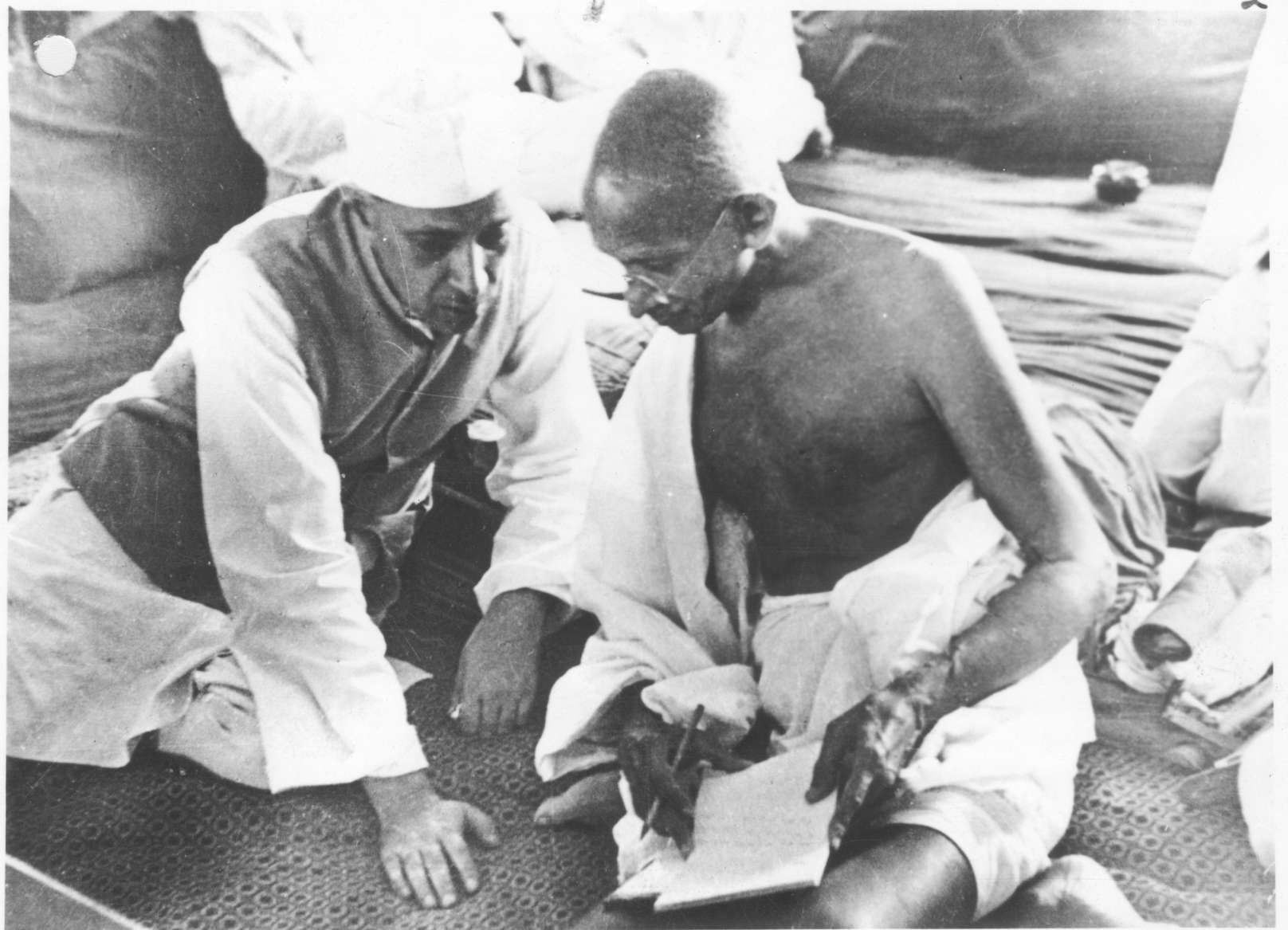

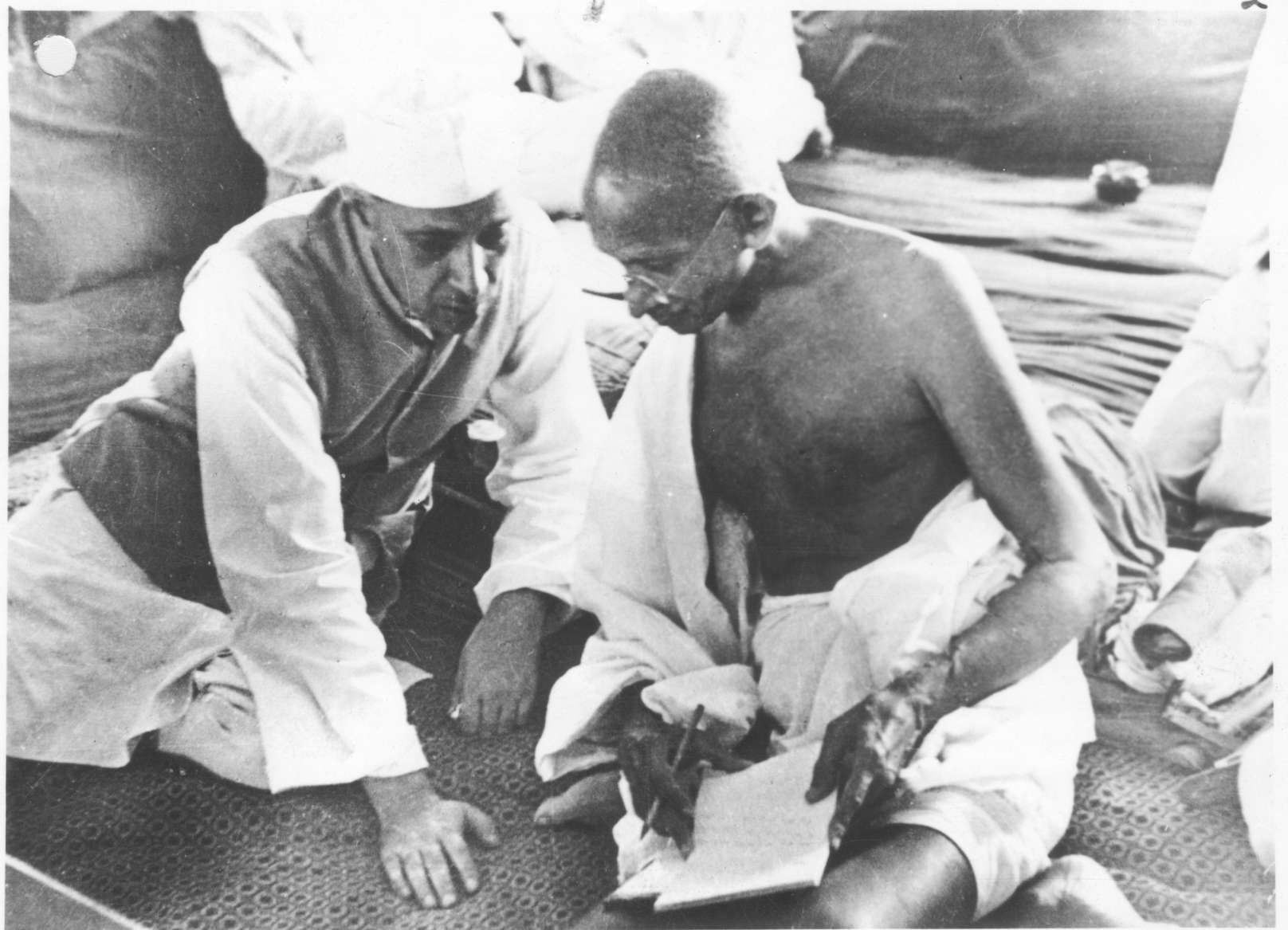

The Quit India Movement, also known as the August Kranti Movement, was a movement launched at the Bombay session of the All India Congress Committee by Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure ...

on 8th August 1942, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, demanding an end to British rule in India.

After the failure of the Cripps Mission to secure Indian support for the British war effort, Gandhi made a call to ''Do or Die'' in his Quit India

The Quit India Movement, also known as the August Kranti Movement, was a movement launched at the Bombay session of the All India Congress Committee by Mahatma Gandhi on 8th August 1942, during World War II, demanding an end to British rule in ...

movement delivered in Bombay on 8 August 1942 at the Gowalia Tank Maidan.

The All India Congress Committee launched a mass protest demanding what Gandhi called "An Orderly British Withdrawal" from India. Even though it was at war, the British were prepared to act. Almost the entire leadership of the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British ...

was imprisoned without trial within hours of Gandhi's speech. Most spent the rest of the war in prison and out of contact with the masses. The British had the support of the Viceroy's Council, of the All India Muslim League, the Hindu Mahasabha, the princely states, the Indian Imperial Police The Indian Imperial Police, referred to variously as the Imperial Police or simply the Indian Police or, by 1905, Imperial Police, was part of the Indian Police Services, the uniform system of police administration in British Raj, as established by ...

, the British Indian Army, and the Indian Civil Service

The Indian Civil Service (ICS), officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the higher civil service of the British Empire in India during British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947.

Its members ruled over more than 300 million ...

. Many Indian businessmen profiting from heavy wartime spending did not support the Quit India Movement. Many students paid more attention to Subhas Chandra Bose

Subhas Chandra Bose ( ; 23 January 1897 – 18 August 1945

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*) was an Indian nationalist whose defiance of British authority in India made him a hero among Indians, but his wartime alliances with Nazi Germany and Imperi ...

, who was in exile and supporting the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

. The only outside support came from the Americans, as President Franklin D. Roosevelt pressured Prime Minister Winston Churchill to give in to some of the Indian demands.

Sporadic small-scale violence took place around the country and the British arrested tens of thousands of leaders, keeping them imprisoned until 1945. Ultimately, the British government realised that India was ungovernable in the long run, and the question for the postwar era became how to exit gracefully and peacefully.

In 1992, the Reserve Bank of India

The Reserve Bank of India, chiefly known as RBI, is India's central bank and regulatory body responsible for regulation of the Indian banking system. It is under the ownership of Ministry of Finance, Government of India. It is responsible f ...

issued a 1 rupee commemorative coin to mark the Golden Jubilee

A golden jubilee marks a 50th anniversary. It variously is applied to people, events, and nations.

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, golden jubilee refers the 50th anniversary year of the separation from Pakistan and is called in Bengali ''"সু ...

of the Quit India Movement.

World War II and Indian involvement

In 1939, Indian nationalists were angry that BritishGovernor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 1 ...

, Lord Linlithgow

Marquess of Linlithgow, in the County of Linlithgow or West Lothian, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 23 October 1902 for John Hope, 7th Earl of Hopetoun. The current holder of the title is Adrian Hope.

This ...

, brought India into the war without consultation with them. The Muslim League supported the war, but Congress was divided.

At the outbreak of war, the Congress Party had passed a resolution during the Wardha meeting of the working-committee in September 1939, conditionally supporting the fight against fascism, but were rebuffed when they asked for independence in return.

Gandhi had not supported this initiative, as he could not reconcile an endorsement for war (he was a committed believer in non-violent resistance, used in the Indian Independence Movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British rule in India. It lasted from 1857 to 1947.

The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged ...

and proposed even against Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

, and Hideki Tojo). However, at the height of the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defended ...

, Gandhi had stated his support for the fight against racism and of the British war effort, stating he did not seek to raise an independent India from the ashes of Britain. However, opinions remained divided. The long-term British policy of limiting investment in India and using the country as a market and source of revenue had left the Indian Army relatively weak and poorly armed and trained and forced the British to become net contributors to India's budget, while taxes were sharply increased and the general level of prices doubled: although many Indian businesses benefited from increased war production, in general business "felt rebuffed by the government" and in particular the refusal of the British Raj to give Indians a greater role in organising and mobilising the economy for wartime production.

After the onset of the war, only a group led by Subhas Chandra Bose

Subhas Chandra Bose ( ; 23 January 1897 – 18 August 1945

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*) was an Indian nationalist whose defiance of British authority in India made him a hero among Indians, but his wartime alliances with Nazi Germany and Imperi ...

took any decisive action. Bose organised the ''Indian Legion

, image = Flag of the Indian Legion.svg

, image_size = 200px

, caption = Flag of the Indian Legion

, country =

, allegiance = Adolf ...

'' in Germany, reorganised the Indian National Army

The Indian National Army (INA; ''Azad Hind Fauj'' ; 'Free Indian Army') was a Collaboration with the Axis powers, collaborationist armed force formed by Indian collaborators and Imperial Japan on 1 September 1942 in Southeast Asia during Worl ...

with Japanese assistance, and soliciting help from the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

, conducted a guerrilla war against the British authorities.

Cripps' Mission

In March 1942, faced with an dissatisfied sub-continent only reluctantly participating in the war and deterioration in the war situation in Europe and with growing dissatisfaction among Indian troops and among the civilian population in the sub-continent, the British government sent a delegation to India underStafford Cripps

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps (24 April 1889 – 21 April 1952) was a British Labour Party politician, barrister, and diplomat.

A wealthy lawyer by background, he first entered Parliament at a by-election in 1931, and was one of a handful of L ...

, the Leader of the House of Commons

The leader of the House of Commons is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom whose main role is organising government business in the House of Commons. The leader is generally a member or attendee of the cabinet of the ...

, in what came to be known as the Cripps mission. The purpose of the mission was to negotiate with the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British ...

a deal to obtain total co-operation during the war, in return for devolution and distribution of power from the crown and the Viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning "k ...

to an elected Indian legislature. The talks failed, as they did not address the key demand of a timetable of self-government and of the powers to be relinquished, essentially making an offer of limited dominion-status that was unacceptable to the Indian movement.

Factors contributing to the movement's launch

In 1939, with the outbreak of war between Germany and Britain, India became a party to the war by being a constituent component of the British Empire. Following this declaration, the Congress Working Committee at its meeting on 10 October 1939, passed a resolution condemning the aggressive activities of the Germans. At the same time, the resolution also stated that India could not associate herself with war unless it was consulted first. Responding to this declaration, the Viceroy issued a statement on 17 October wherein he claimed that Britain is waging a war driven with the intention of strengthening peace in the world. He also stated that after the war, the government would initiate modifications in the Act of 1935, in accordance with the desires of the Indians. Gandhi's reaction to this statement was; "the old policy of divide and rule is to continue. Congress has asked for bread and it has got stone." According to the instructions issued by High Command, the Congress ministers were directed to resign immediately. Congress ministers from eight provinces resigned following the instructions. The resignation of the ministers was an occasion of great joy and rejoicing for the leader of the Muslim League,Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (, ; born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai; 25 December 1876 – 11 September 1948) was a barrister, politician, and the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until the ...

. He called the date i.e. 22 December 1939 ' The Day of Deliverance'. Gandhi urged Jinnah against the celebration of this day, however, it was futile. At the Muslim League Lahore Session held in March 1940, Jinnah declared in his presidential address that the Muslims of the country wanted a separate electorate, Pakistan.

In the meanwhile, crucial political events took place in England. Chamberlain was succeeded by Churchill as prime minister and the Conservatives, who assumed power in England, did not have a sympathetic stance towards the claims made by the Congress. In order to pacify the Indians in the circumstance of the worsening war situation, the Conservatives were forced to concede some of the demands made by the Indians. On 8 August, the Viceroy issued a statement that has come to be referred to as the "August Offer

The August Offer was an offer made by Viceroy Linlithgow in 1940 promising the expansion of the Executive Council of the Viceroy of India to include more Indians, the establishment of an advisory war council, giving full weight to minority opini ...

". However, Congress rejected the offer followed by the Muslim League.

In the context of widespread dissatisfaction that prevailed over the rejection of the demands made by the Congress, at the meeting of the Congress Working Committee in Wardha, Gandhi revealed his plan to launch individual civil disobedience. Once again, the weapon of satyagraha

Satyāgraha ( sa, सत्याग्रह; ''satya'': "truth", ''āgraha'': "insistence" or "holding firmly to"), or "holding firmly to truth",' or "truth force", is a particular form of nonviolent resistance or civil resistance. Someone w ...

found popular acceptance as the best means to wage a crusade against the British. It was widely used as a mark of protest against the unwavering stance assumed by the British. Vinoba Bhave, a follower of Gandhi, was selected by him to initiate the movement. Anti-war speeches ricocheted in all corners of the country, with the satyagrahis earnestly appealing to the people of the nation not to support the government in its war endeavours. The consequence of this satyagrahi campaign was the arrest of almost fourteen thousand satyagrahis. On 3 December 1941, the Viceroy ordered the acquittal of all the satyagrahis. In Europe the war situation became more critical with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the Congress realised the necessity for appraising their program. Subsequently, the movement was withdrawn.

The Cripps' Mission of March (1942) and its failure also played an important role in Gandhi's call for The Quit India Movement. In order to end the deadlock on 22 March 1942, the British government sent Sir Stafford Cripps to talk terms with the Indian political parties and secure their support in Britain's war efforts. A draft declaration of the British Government was presented, which included terms like the establishment of Dominion, the establishment of a Constituent Assembly, and right of the provinces to make separate constitutions. However, these were to be only after the cessation of the Second World War. According to Congress, this declaration offered India an only promise that was to be fulfilled in the future. Commenting on this Gandhi said, "It is a post-dated cheque on a crashing bank." Other factors that contributed were the threat of Japanese invasion of India and the realisation of the national leaders of the incapacity of the British to defend India.

Resolution for immediate independence

The Congress Working Committee meeting at Wardha (14 July 1942) adopted a resolution demanding complete independence from theBritish government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_est ...

. The draft proposed massive civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a stat ...

if the British did not accede to the demands. It was passed at Bombay

However, it proved to be controversial within the party. A prominent Congress national leader, Chakravarti Rajgopalachari, quit the Congress over this decision, and so did some local and regional level organisers. Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

and Maulana Azad

Abul Kalam Ghulam Muhiyuddin Ahmed bin Khairuddin Al- Hussaini Azad (; 11 November 1888 – 22 February 1958) was an Indian independence activist, Islamic theologian, writer and a senior leader of the Indian National Congress. Following I ...

were apprehensive and critical of the call, but backed it and stuck with Gandhi's leadership

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to "lead", influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word "leadership" often gets v ...

until the end. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel (; ; 31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), commonly known as Sardar, was an Indian lawyer, influential political leader, barrister and statesman who served as the first Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister of ...

, Rajendra Prasad

Rajendra Prasad (3 December 1884 – 28 February 1963) was an Indian politician, lawyer, Indian independence activist, journalist & scholar who served as the first president of Republic of India from 1950 to 1962. He joined the Indian Nationa ...

and Anugrah Narayan Sinha openly and enthusiastically supported such a disobedience movement, as did many veteran Gandhians and socialists like Asoka Mehta and Jayaprakash Narayan

Jayaprakash Narayan (; 11 October 1902 – 8 October 1979), popularly referred to as JP or ''Lok Nayak'' (Hindi for "People's leader"), was an Indian independence activist, theorist, socialist and political leader. He is remembered for le ...

.

Allama Mashriqi (head of the Khaksar Tehrik) was called by Jawaharlal Nehru to join the Quit India Movement. Mashriqi was apprehensive of its outcome and did not agree with the Congress Working Committee's resolution. On 28 July 1942, Allama Mashriqi sent the following telegram to Maulana Abul Kalam Azad

Abul Kalam Ghulam Muhiyuddin Ahmed bin Khairuddin Al- Hussaini Azad (; 11 November 1888 – 22 February 1958) was an Indian independence activist, Islamic theologian, writer and a senior leader of the Indian National Congress. Following In ...

, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Mohandas Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, C. Rajagopalachari, Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

, Rajendra Prasad

Rajendra Prasad (3 December 1884 – 28 February 1963) was an Indian politician, lawyer, Indian independence activist, journalist & scholar who served as the first president of Republic of India from 1950 to 1962. He joined the Indian Nationa ...

and Pattabhi Sitaramayya. He also sent a copy to Bulusu Sambamurti (former Speaker of the Madras Assembly

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

). The telegram was published in the press, and stated:

The resolution said:

Opposition to the Quit India Movement

Several political groups active during the

Several political groups active during the Indian Independence Movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British rule in India. It lasted from 1857 to 1947.

The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged ...

were opposed to the Quit India Movement. These included the Muslim League, the Hindu Mahasabha and princely states

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

as below:

Hindu Mahasabha

Hindu nationalist parties like the Hindu Mahasabha openly opposed the call for the Quit India Movement and boycotted it officially.Vinayak Damodar Savarkar

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (), Marathi pronunciation: �inaːjək saːʋəɾkəɾ also commonly known as Veer Savarkar (28 May 1883 – 26 February 1966), was an Indian politician, activist, and writer.

Savarkar developed the Hindu nationa ...

, the president of the Hindu Mahasabha at that time, even went to the extent of writing a letter titled "''Stick to your Posts''", in which he instructed Hindu Sabhaites who happened to be "members of municipalities, local bodies, legislatures or those serving in the army... to stick to their posts" across the country, and not to join the Quit India Movement at any cost. But later after requests and persuasions and realising the importance of the bigger role of Indian independence he chose to join the Indian independence movement.

Following the Hindu Mahasabha's official decision to boycott the Quit India movement, Syama Prasad Mukherjee, leader of the Hindu Mahasabha in Bengal, (which was a part of the ruling coalition in Bengal led by Krishak Praja Party

The Krishak Sramik Party ( bn, কৃষক শ্রমিক পার্টি, ''Farmer Labourer Party'') was a major anti-feudal political party in the British Indian province of Bengal and later in the Dominion of Pakistan's East Bengal an ...

of Fazlul Haq), wrote a letter to the British Government as to how they should respond, if the Congress gave a call to the British rulers to quit India. In this letter, dated 26 July 1942 he wrote:“Let me now refer to the situation that may be created in the province as a result of any widespread movement launched by the Congress. Anybody, who during the war, plans to stir up mass feeling, resulting internal disturbances or insecurity, must be resisted by any Government that may function for the time being”. In this way he managed to gain insights of the British government and effectively give information of the independence leaders.Mukherjee reiterated that the Fazlul Haq led Bengal Government, along with its alliance partner Hindu Mahasabha, would make every possible effort to defeat the Quit India Movement in the province of Bengal and made a concrete proposal as regards this:

“The question is how to combat this movement (Quit India) in Bengal? The administration of the province should be carried on in such a manner that in spite of the best efforts of the Congress, this movement will fail to take root in the province. It should be possible for us, especially responsible Ministers, to be able to tell the public that the freedom for which the Congress has started the movement, already belongs to the representatives of the people. In some spheres it might be limited during the emergency. Indian have to trust the British, not for the sake for Britain, not for any advantage that the British might gain, but for the maintenance of the defence and freedom of the province itself. You, as Governor, will function as the constitutional head of the province and will be guided entirely on the advice of your Minister.The Indian historian R.C. Majumdar noted this fact and states:

"Shyam Prasad ended the letter with a discussion of the mass movement organised by the Congress. He expressed the apprehension that the movement would create internal disorder and will endanger internal security during the war by exciting popular feeling and he opined that any government in power has to suppress it, but that according to him could not be done only by persecution.... In that letter he mentioned item wise the steps to be taken for dealing with the situation .... "

Princely States

The movement had less support in the princely states, as the princes were strongly opposed and funded the opposition. The Indian nationalists had very little international support. They knew that the United States strongly supported Indian independence, in principle, and believed the U.S. was an ally. However, after Churchill threatened to resign if pushed too hard, the U.S. quietly supported him while bombarding Indians with propaganda designed to strengthen public support of the war effort. The poorly run American operation annoyed the Indians.Local violence and parallel governments

Contai

Contai is a coastal and subdivisional city and a municipality in Purba Medinipur district, West Bengal, India. It is the headquarters of the Contai subdivision. It is the second most populated city of the district.According to the geologists, t ...

subdivisions of Midnapore, the local populace were successful in establishing parallel government Tamluk National Government, which continued to function, until Gandhi personally requested the leaders to disband in 1944. A minor uprising took place in Ballia

Ballia is a city with a municipal board in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. The eastern boundary of the city lies at the junction of two major rivers, the Ganges and the Ghaghara.The city is situated east of Varanasi and about 380 km f ...

, now the easternmost district of Uttar Pradesh. People overthrew the district administration, broke open the jail, released the arrested Congress leaders and established their own independent rule. It took weeks before the British could reestablish their writ in the district. Of special importance in Saurashtra (in western Gujarat) was the role of the region's 'baharvatiya' tradition (i.e. going outside the law) which abetted the sabotage activities of the movement there. In Adas village in Kaira district, six people died and many more wounded in police shooting incident.

In rural west Bengal, the Quit India Movement was fuelled by peasants' resentment against the new war taxes and the forced rice exports. There was open resistance to the point of rebellion in 1942 until the great famine of 1943 suspended the movement.

Suppression of the movement

One of the important achievements of the movement was keeping the Congress party united through all the trials and tribulations that followed. The British, already alarmed by the advance of the Japanese army to the India-Burma border, responded by imprisoning Gandhi. All the members of the Party's Working Committee (national leadership) were imprisoned as well. Due to the arrest of major leaders, a young and until then relatively unknown Aruna Asaf Ali presided over the AICC session on 9 August and hoisted the flag; later the Congress party was banned. These actions only created sympathy for the cause among the population. Despite lack of direct leadership, large protests and demonstrations were held all over the country. Workers remained absent in large groups and strikes were called. Not all demonstrations were peaceful, at some places bombs exploded, government buildings were set on fire, electricity was cut and transport and communication lines were severed. The British swiftly responded with mass detentions. Over 100,000 arrests were made, mass fines were levied and demonstrators were subjected to public flogging. Hundreds of civilians were killed in violence many shot by the police army. Many national leaders went underground and continued their struggle by broadcasting messages over clandestineradio

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transm ...

stations, distributing pamphlets and establishing parallel governments. The British sense of crisis was strong enough that a battleship was specifically set aside to take Gandhi and the Congress leaders out of India, possibly to South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring count ...

or Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast an ...

but ultimately did not take that step out of fear of intensifying the revolt.

The Congress leadership was cut off from the rest of the world for over three years. Gandhi's wife Kasturba Gandhi

Kasturbai Mohandas Gandhi (, born Kasturbai Gokuldas Kapadia; 11 April 1869 – 22 February 1944) was an Indian political activist. She married Mohandas Gandhi, more commonly known as Mahatma Gandhi, in 1883. With her husband and her eldest so ...

and his personal secretary Mahadev Desai died in months and Gandhi's health was failing, despite this Gandhi went on a 21-day fast and maintained his resolve to continuous resistance. Although the British released Gandhi on account of his health in 1944, he kept up the resistance, demanding the release of the Congress leadership.

By early 1944, India was mostly peaceful again, while the Congress leadership was still incarcerated. A sense that the movement had couldn't gain enough success depressed many nationalists, while Jinnah and the Muslim League, as well as Congress opponents such as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh ( ; , , ) is an Indian right-wing, Hindu nationalist, paramilitary volunteer organisation. The RSS is the progenitor and leader of a large body of organisations called the Sangh Parivar (Hindi for "Sangh family ...

and the Hindu Mahasabha sought to gain political mileage, criticising Gandhi and the Congress Party.

See also

* Bhadant Anand Kausalyayan *British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi language, Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Q ...

* Government of Azad Hind

*Indian Independence Movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British rule in India. It lasted from 1857 to 1947.

The first nationalistic revolutionary movement for Indian independence emerged ...

*Indian nationalism

Indian nationalism is an instance of territorial nationalism, which is inclusive of all of the people of India, despite their diverse ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds. Indian nationalism can trace roots to pre-colonial India, ...

* Kallara-Pangode Struggle

*Non-Cooperation Movement

The Non-cooperation movement was a political campaign launched on 4 September 1920, by Mahatma Gandhi to have Indians revoke their cooperation from the British government, with the aim of persuading them to grant self-governance.Rahul Sankrityayan

online edition

* * * Hutchins, Francis G. ''India's Revolution: Gandhi and the Quit India Movement'' (1973) * * Krishan, Shri. "Crowd vigour and social identity: The Quit India Movement in western India." ''Indian Economic & Social History Review'' 33.4 (1996): 459–479. * Panigrahi; D. N. ''India's Partition: The Story of Imperialism in Retreat'' (Routledge, 2004

online edition

* * Patil, V. I. ''Gandhiji, Nehruji and the Quit India Movement'' (1984) * Read, Anthony, and David Fisher; ''The Proudest Day: India's Long Road to Independence'' (W. W. Norton, 1999

online edition

detailed scholarly history * Venkataramani, M. S.; Shrivastava, B. K. ''Quit India: The American Response to the 1942 Struggle'' (1979) * * Muni, S. D. "The Quit India Movement: A Review Article," ''International Studies,'' (Jan 1977,) 16#1 pp 157–168, * Shourie, Arun (1991). "The Only fatherland": Communists, "Quit India", and the Soviet Union. New Delhi: ASA Publications. * Mansergh, Nicholas, and E. W. R. Lumby, eds. ''India: The Transfer of Power 1942–7. Vol. II. 'Quit India' 30 April-21 September 1942'' (London:

online

*

{{Authority control 1942 protests 1942 establishments in India 1942 in India Gandhism Articles containing video clips India in World War II British Empire in World War II Asian resistance to colonialism

References

Works cited

*Further reading

* Akbar, M.J. ''Nehru: The Making of India'' (Viking, 1988), popular biography * * * * * Clymer, Kenton J. ''Quest for Freedom: The United States and India's Independence'' (Columbia University Press, 1995online edition

* * * Hutchins, Francis G. ''India's Revolution: Gandhi and the Quit India Movement'' (1973) * * Krishan, Shri. "Crowd vigour and social identity: The Quit India Movement in western India." ''Indian Economic & Social History Review'' 33.4 (1996): 459–479. * Panigrahi; D. N. ''India's Partition: The Story of Imperialism in Retreat'' (Routledge, 2004

online edition

* * Patil, V. I. ''Gandhiji, Nehruji and the Quit India Movement'' (1984) * Read, Anthony, and David Fisher; ''The Proudest Day: India's Long Road to Independence'' (W. W. Norton, 1999

online edition

detailed scholarly history * Venkataramani, M. S.; Shrivastava, B. K. ''Quit India: The American Response to the 1942 Struggle'' (1979) * * Muni, S. D. "The Quit India Movement: A Review Article," ''International Studies,'' (Jan 1977,) 16#1 pp 157–168, * Shourie, Arun (1991). "The Only fatherland": Communists, "Quit India", and the Soviet Union. New Delhi: ASA Publications. * Mansergh, Nicholas, and E. W. R. Lumby, eds. ''India: The Transfer of Power 1942–7. Vol. II. 'Quit India' 30 April-21 September 1942'' (London:

Her Majesty's Stationery Office

The Office of Public Sector Information (OPSI) is the body responsible for the operation of His Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO) and of other public information services of the United Kingdom. The OPSI is part of the National Archives of the Un ...

, 1971), 1044ponline

*

External links

{{Authority control 1942 protests 1942 establishments in India 1942 in India Gandhism Articles containing video clips India in World War II British Empire in World War II Asian resistance to colonialism