Quapaw on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Quapaw ( ; or Arkansas and Ugahxpa) people are a tribe of Native Americans that coalesced in what is known as the Midwest and Ohio Valley of the present-day United States. The

''Neosho Daily News'', 19 January 2013 (retrieved 8 February 2013) In 2020 they completed a third casino,

"Osage"

''Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture'', retrieved 2 March 2009 The Quapaw reached their historical territory, the area of the

Shortly after the United States acquired the territory in 1803 by the

Shortly after the United States acquired the territory in 1803 by the

In the early 20th century, an account noted that the Dhegiha language, a branch of Siouan including the "dialects" of the Omaha, Ponca, Osage, Kansa, and Quapaw, has received more extended study. Rev. J.O. Dorsey published material about it under the auspices of the

In the early 20th century, an account noted that the Dhegiha language, a branch of Siouan including the "dialects" of the Omaha, Ponca, Osage, Kansa, and Quapaw, has received more extended study. Rev. J.O. Dorsey published material about it under the auspices of the

Quapaw Tribe

official website

Quapaw Tribal Ancestry

official tribal sanctioned site with genealogy information, pictures, and stories

official tribal sanctioned site with language information, words, audio clips, and source information

Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

EPA

Access Genealogy

Tar Creek

Tar Creek documentary website {{DEFAULTSORT:Quapaw Dhegiha Siouan peoples Federally recognized tribes in the United States American Indian reservations in Oklahoma Native American tribes in Arkansas Native American tribes in Oklahoma

Dhegiha Siouan

The Dhegihan languages are a group of Siouan languages that include Kansa– Osage, Omaha–Ponca, and Quapaw. Their historical region included parts of the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys, the Great Plains, and southeastern North America. ...

-speaking tribe historically migrated from the Ohio Valley area to the west side of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

in what is now the state of Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

; their name for themselves (or autonym) refers to this migration and to traveling downriver.

The Quapaw are federally recognized

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United ...

as the Quapaw Nation. The US federal government forcibly removed them to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

in 1834, and their tribal base has been in present-day Ottawa County in northeastern Oklahoma. The number of members enrolled in the tribe was 3,240 in 2011.

Name

Algonquian-speaking people called the Quapaw ''akansa''. French explorers and colonists learned this term from Algonquians and adapted it in French as ''Arcansas''. The French named theArkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

and the territory of Arkansas for them.

Government

The Quapaw Nation is headquartered inQuapaw

The Quapaw ( ; or Arkansas and Ugahxpa) people are a tribe of Native Americans that coalesced in what is known as the Midwest and Ohio Valley of the present-day United States. The Dhegiha Siouan-speaking tribe historically migrated from the Oh ...

in Ottawa County, Oklahoma

Ottawa County is a county located in the northeastern corner of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2020 census, the population was 30,285. Its county seat is Miami. The county was named for the Ottawa Tribe of Oklahoma.tribal jurisdictional area

Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area is a statistical entity identified and delineated by federally recognized American Indian tribes in Oklahoma as part of the U.S. Census Bureau's 2010 Census and ongoing American Community Survey.

Many of these ...

.

The Quapaw people elect a tribal council and the tribal chairman, who serves a two-year term. The governing body of the tribe is outlined in the governing resolutions of the tribe, which were voted upon and approved in 1956 to create a written form of government. (Prior to 1956 the Quapaw Tribe operated on a traditional, hereditary chief system). The Chairman is Joseph T. Byrd. Of the 3,240 enrolled tribal members, 892 live in the state of Oklahoma. Membership in the tribe is based on lineal descent.

The tribe operates a Tribal Police Department and a Fire Department, which handles both fire and EMS calls. They issue their own tribal vehicle tags

Several Native American tribes within the United States register motor vehicles and issue license plates to those vehicles.

The legal status of these plates varies by tribe, with some being recognized by the federal government and others not. So ...

and have their own housing authority.

Economic development

The tribe owns two smoke shops and motor fuel outlets, known as the Quapaw C-Store and Downstream Q-Store. They also own and operate the Eagle Creek Golf Course and resort, located inLoma Linda, Missouri

Loma Linda is a village in Newton County, Missouri, United States. The population was 725 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Joplin, Missouri Metropolitan Statistical Area. The village, a collection of homes and properties surrounding the gol ...

.

Their primary economic drivers have been their gaming casinos, established under federal and state law. The first two are both located in Quapaw: the Quapaw Casino and the Downstream Casino Resort. These have generated most of the revenue for the tribe, which they have used to support welfare, health and education of their members. In 2012 the Quapaw Tribe's annual economic impact in the region was measured at more than $225,000,000."Casino Pumps 1 Billion: Downstream Casino Economic Impact"''Neosho Daily News'', 19 January 2013 (retrieved 8 February 2013) In 2020 they completed a third casino,

Saracen Casino Resort

Saracen Casino Resort is a casino in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, United States. The first purpose-built casino in Arkansas, it is owned by the Quapaw Nation, and named for Saracen, a Quapaw chief in the 1800s.

History

The first section of the casino, ...

, located in Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Pine Bluff is the eleventh-largest city in the state of Arkansas and the county seat of Jefferson County. It is the principal city of the Pine Bluff Metropolitan Statistical Area and part of the Little Rock-North Little Rock-Pine Bluff Combin ...

. It was the first purpose-built casino in the state. Constructed at a cost of $350 million, it will employ over 1,100 full-time staff.

In the 20th century, the Quapaw leased some of their lands to European Americans, who developed them for industrial purposes. Before passage of environmental laws, toxic waste was deposited that has created long-term hazards. For instance, the Tar Creek Superfund site

Tar Creek Superfund site is a United States Superfund site, declared in 1983, located in the cities of Picher and Cardin, Ottawa County, in northeastern Oklahoma. From 1900 to the 1960s lead mining and zinc mining companies left behind huge ope ...

has been listed by the Environmental Protection Agency as requiring clean-up of environmental hazards.

Language

The traditionalQuapaw language

Quapaw, or Arkansas, is a Siouan language of the Quapaw people, originally from a region in present-day Arkansas. It is now spoken in Oklahoma.

It is similar to the other Dhegihan languages: Kansa, Omaha, Osage and Ponca.

Written documentat ...

is part of the Dhegiha

The Dhegihan languages are a group of Siouan languages that include Kansa– Osage, Omaha–Ponca, and Quapaw. Their historical region included parts of the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys, the Great Plains, and southeastern North America. T ...

branch of the Siouan language family. Quapaw was well documented in fieldnotes and publications from many individuals, including George Izard

George Izard (October 21, 1776 – November 22, 1828) was a senior officer of the United States Army who served as the second governor of Arkansas Territory from 1825 to 1828. He was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society in 18 ...

in 1827, Lewis F. Hadley in 1882, 19th-century linguist

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

James Owen Dorsey

James Owen Dorsey (October 31, 1848 – February 4, 1895) was an American ethnologist, linguist, and Episcopalian missionary in the Dakota Territory, who contributed to the description of the Ponca, Omaha, and other southern Siouan languages. He ...

, Frank T. Siebert in 1940, and linguist Robert Rankin in the 1970s. In the 21st century, there are few remaining native speakers.

To revive the language, the tribe is conducting classes in Quapaw at the tribal museum. An online audio lexicon of the Quapaw language was created by editing old recordings of Elders speaking the language.

Other efforts at language preservation and revitalization are being undertaken. In 2011 the Quapaw participated in the first annual Dhegiha Gathering. The Osage language

Osage (; Osage: ''Wažáže ie'') is a Siouan language that is spoken by the Osage people of Oklahoma. Their original territory was in present-day Missouri and Kansas but they were gradually pushed west by European-American pressure and treati ...

program hosted and organized the gathering, held at the Quapaw tribe's Downstream Casino. Language-learning techniques and other issues were discussed and taught in workshops at the conference among the five cognate tribes. The 2012 Annual Dhegiha Gathering was also held at Downstream Casino.

Cultural heritage

The Quapaw host cultural events throughout the year, which are primarily held at the tribal museum. These include Indian dice games, traditional singing, and classes in traditional arts, such as finger weaving, shawl making, and flute making. In addition, Quapaw language classes are held there.Fourth of July

The tribe's annual dance is during the weekend of the Fourth of July. This dance was organized shortly after theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, 2011 was the 139th anniversary of this dance. Common features of this powwow include gourd dance

The Gourd Dance is a social dance.

Origin legends

Many Native Americans dispute the origin of the legend of the Gourd Dance. A Kiowa story recounts the tale of a young man who had been separated from the rest of the tribe. Hungry and dehydrated ...

, war dance, stomp dance, and 49s. Other activities take place such as Indian football, handgame

Handgame, also known as stickgame, is a Native American guessing game, in which marked "bones" are concealed in the hands of one team while another team guesses their location.

Gameplay

Any number of people can play the Hand Game, but each team ...

, traditional footraces, traditional dinners, turkey dance, and other dances such as Quapaw Dance, and dances from other area tribes.

This weekend is also when the tribe convenes the annual general council meeting, during which important decisions regarding the policies and resolutions of the Quapaw tribe are voted upon by tribal members over the age of eighteen.

History

The Quapaw Nation (known as ' in their own language) are descended from a historical group of Dhegihan-Siouan speaking people who lived in the lower Ohio River valley area. The modern descendants of this language group include the Omaha,Ponca

The Ponca ( Páⁿka iyé: Páⁿka or Ppáⁿkka pronounced ) are a Midwestern Native American tribe of the Dhegihan branch of the Siouan language group. There are two federally recognized Ponca tribes: the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska and the Ponca ...

, Osage and Kaw

Kaw or KAW may refer to:

Mythology

* Kaw (bull), a legendary bull in Meitei mythology

* Johnny Kaw, mythical settler of Kansas, US

* Kaw (character), in ''The Chronicles of Prydain''

People

* Kaw people, a Native American tribe

Places

* Kaw, Fr ...

, all independent nations. The Quapaw and the other Dhegiha Siouan speaking tribes are believed to have migrated west and south from the Ohio River valley

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illinoi ...

after 1200 CE.

Scholars are divided as to whether they think the Quapaw and other related groups left before or after the Beaver Wars

The Beaver Wars ( moh, Tsianì kayonkwere), also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars (french: Guerres franco-iroquoises) were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout t ...

of the 17th century, in which the more powerful Five Nations of the Iroquois (based south of the Great Lakes and to the east of this area), drove other tribes out of the Ohio Valley and retained the area for hunting grounds.Louis F. Burns"Osage"

''Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture'', retrieved 2 March 2009 The Quapaw reached their historical territory, the area of the

confluence

In geography, a confluence (also: ''conflux'') occurs where two or more flowing bodies of water join to form a single channel. A confluence can occur in several configurations: at the point where a tributary joins a larger river (main stem); o ...

of the Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

and Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

rivers, at least by the mid-17th century. The timing of the Quapaw migration into their ancestral territory in the historical period has been the subject of considerable debate by scholars of various fields. It is referred to as the "Quapaw Paradox" by academics. Many professional archaeologists have introduced numerous migration scenarios and time frames, but none has conclusive evidence. Glottochronological studies suggest the Quapaw separated from the other Dhegihan-speaking peoples in a period ranging between AD 950 to as late as AD 1513.

The Illinois and other Algonquian-speaking peoples to the northeast referred to these people as the ' or ', referring to geography and meaning "land of the downriver people". As French explorers Jacques Marquette

Jacques Marquette S.J. (June 1, 1637 – May 18, 1675), sometimes known as Père Marquette or James Marquette, was a French Jesuit missionary who founded Michigan's first European settlement, Sault Sainte Marie, and later founded Saint Ign ...

and Louis Jolliet

Louis Jolliet (September 21, 1645after May 1700) was a French-Canadian explorer known for his discoveries in North America. In 1673, Jolliet and Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit Catholic priest and missionary, were the first non-Natives to explore and ...

encountered and interacted with the Illinois before they did the Quapaw, they adopted this exonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, ...

for the more westerly people. In their language, they referred to them as ''Arcansas''. English-speaking settlers who arrived later in the region adopted the name used by the French, and adapted it to English spelling conventions.

During years of colonial rule of New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spai ...

, many of the ethnic French fur traders and ''voyageurs

The voyageurs (; ) were 18th and 19th century French Canadians who engaged in the transporting of furs via canoe during the peak of the North American fur trade. The emblematic meaning of the term applies to places (New France, including the ' ...

'' had an amicable relationship with the Quapaw, as they did with many other trading tribes. Many Quapaw women and French men married and had families together. Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Pine Bluff is the eleventh-largest city in the state of Arkansas and the county seat of Jefferson County. It is the principal city of the Pine Bluff Metropolitan Statistical Area and part of the Little Rock-North Little Rock-Pine Bluff Combin ...

, was founded by Joseph Bonne, a man of Quapaw-French ancestry.

'' Écore Fabre'' (Fabre's Bluff) was started as a trading post by the Frenchman Fabre and was one of the first European settlements in south-central Arkansas. While the area was nominally ruled by the Spanish from 1763–1789, following French defeat in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

, they did not have many colonists in the area and did not interfere with the French. The United States acquired the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

in 1803, which stimulated migration of English-speaking settlers to this area. They renamed ''Écore Fabre'' as Camden.

English speakers typically transliterated French names to English phonetics: ' (French for "covered way or road") was gradually converted to "Smackover" by Anglo-Americans. They used this name for a local creek. ', founded by the French, was translated by English speakers and renamed as Little Rock

( The "Little Rock")

, government_type = Council-manager

, leader_title = Mayor

, leader_name = Frank Scott Jr.

, leader_party = D

, leader_title2 = Council

, leader_name2 ...

by Americans after the Louisiana Purchase.

Numerous spelling variations have been recorded in accounts of tribal names, reflecting both loose spelling traditions, and the effects of transliteration of names into the variety of European languages used in the area. Some sources listed ''Ouachita'' as a Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

word, whereas others list it as a Quapaw word. Either way, the spelling reflects transliteration into French.

The following passages are taken from the public domain ''Catholic Encyclopedia'', written early in the 20th century. It describes the Quapaw from the non-native perspective of that time. Some of the tribe has strong Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

kin relationships then and now.

A tribe now nearly extinct, but formerly one of the most important of the lowerMississippi Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...region, occupying several villages about the mouth of theArkansas Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ..., chiefly on the west (Arkansas Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...) side, with one or two at various periods on the east (Mississippi Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...) side of the Mississippi, and claiming the whole of the Arkansas River region up to the border of the territory held by the Osage in the north-western part of the state. They are ofSiouan Siouan or Siouan–Catawban is a language family of North America that is located primarily in the Great Plains, Ohio and Mississippi valleys and southeastern North America with a few other languages in the east. Name Authors who call the enti ...linguistic stock, speaking the same language, spoken also with dialectic variants, by the Osage and Kansa (Kaw Kaw or KAW may refer to: Mythology * Kaw (bull), a legendary bull in Meitei mythology * Johnny Kaw, mythical settler of Kansas, US * Kaw (character), in ''The Chronicles of Prydain'' People * Kaw people, a Native American tribe Places * Kaw, Fr ...) in the south and by the Omaha andPonca The Ponca ( Páⁿka iyé: Páⁿka or Ppáⁿkka pronounced ) are a Midwestern Native American tribe of the Dhegihan branch of the Siouan language group. There are two federally recognized Ponca tribes: the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska and the Ponca ...inNebraska Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe .... Their name properly is ''Ugakhpa'', which signifies "down-stream people", as distinguished from ''Umahan'' or Omaha, "up-stream people". To theIllinois Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...and other Algonquian tribes, they were known as 'Akansea', whence their French names of ''Akensas'' and ''Akansas''. According to concurrent tradition of the cognate tribes, the Quapaw and their kinsmen originally lived far east, possibly beyond theAlleghenies The Allegheny Mountain Range (; also spelled Alleghany or Allegany), informally the Alleghenies, is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the Eastern United States and Canada and posed a significant barrier to land travel in less develo ..., and, pushing gradually westward, descended theOhio River The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...– hence called by the Illinois the "river of the Akansea" – to its junction with the Mississippi, whence the Quapaw, then including the Osage and Kansa, descended to the mouth of the Arkansas, while the Omaha, with thePonca The Ponca ( Páⁿka iyé: Páⁿka or Ppáⁿkka pronounced ) are a Midwestern Native American tribe of the Dhegihan branch of the Siouan language group. There are two federally recognized Ponca tribes: the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska and the Ponca ..., went up theMissouri Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ....

Early European contact

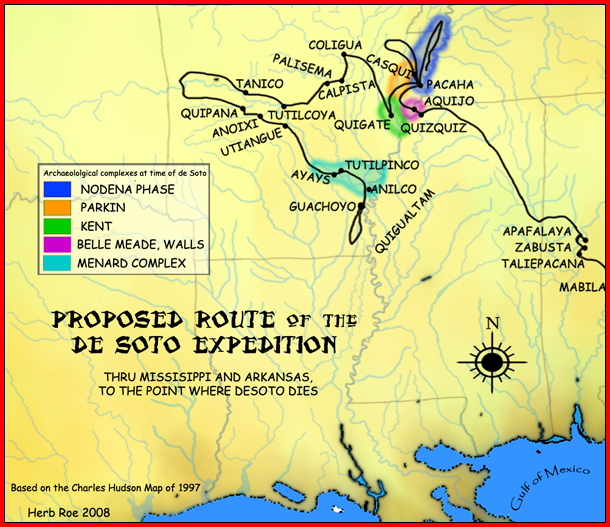

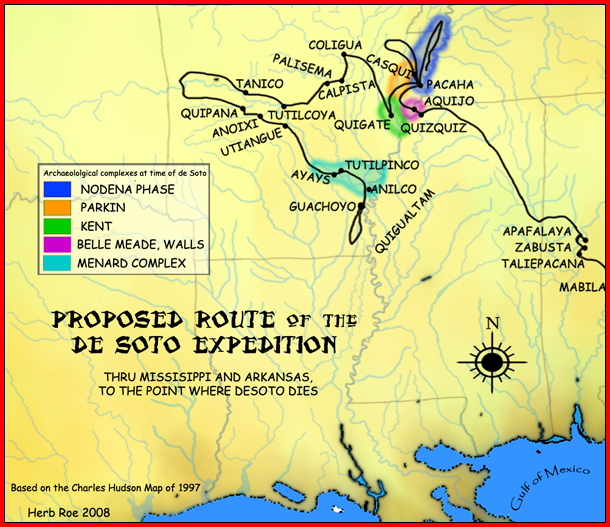

In 1541, when the Spanish explorerHernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

led an expedition that came across the town of ''Pacaha

Pacaha was a Native American polity encountered in 1541 by the Hernando de Soto expedition. This group inhabited fortified villages in what is today the northeastern portion of the U.S. state of Arkansas.

The tribe takes its name from the chieft ...

'' (also recorded by Garcilaso as ''Capaha''), between the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

and a lake on the Arkansas side, apparently in present-day Phillips County. His party described the village as strongly palisaded and nearly surrounded by a ditch. Archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

remains and local conditions bear out the description. If the migration from the Ohio Valley preceded the ''entrada'', these people may have been the proto-Quapaw. But the expedition's chronicler recorded that the Tunica language

The Tunica or Luhchi Yoroni (or Tonica, or less common form Yuron) language is a language isolate that was spoken in the Central and Lower Mississippi Valley in the United States by Native American Tunica peoples. There are no native speakers o ...

was used in Pacaha and there is evidence for a later Quapaw migration to Arkansas. It is likely that de Soto and his expedition met Tunica there.

The first certain encounters with Quapaw by Europeans occurred more than 130 years later. In 1673, the Jesuit Father Jacques Marquette

Jacques Marquette S.J. (June 1, 1637 – May 18, 1675), sometimes known as Père Marquette or James Marquette, was a French Jesuit missionary who founded Michigan's first European settlement, Sault Sainte Marie, and later founded Saint Ign ...

accompanied the French commander Louis Jolliet

Louis Jolliet (September 21, 1645after May 1700) was a French-Canadian explorer known for his discoveries in North America. In 1673, Jolliet and Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit Catholic priest and missionary, were the first non-Natives to explore and ...

in traveling down the Mississippi by canoe. He reportedly went to the villages of the ''Akansea'', who gave him warm welcome and listened with attention to his sermons, while he stayed with them a few days. In 1682 La Salle passed by their villages, then five in number, including one on the east bank of the Mississippi. Zenobius Membré, a Recollect father who accompanied the LaSalle expedition, planted a cross and attempted to convert the Native Americans to Christianity.

La Salle negotiated a peace with the tribe and formally "claimed" the territory for France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. The Quapaw were recorded as uniformly kind and friendly toward the French. While villages relocated in the area, four Quapaw villages were generally reported by Europeans along the Mississippi River in this early period. They corresponded in name and population to four sub-tribes still existing, listed as ', ', ', and '. The French transliterations were: Kappa, Ossoteoue, Touriman, and Tonginga.

Kappa was reported to have been on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, and the other three located on the western bank in or near present-day Desha County, Arkansas

Desha County ( ) is a county located in the southeast part of the U.S. state of Arkansas, with its eastern border the Mississippi River. At the 2010 census, the population was 13,008. It ranks 56th of Arkansas's 75 counties in terms of populat ...

. In 1721 depopulation led to the consolidation of Tourima and Tongigua into one village. Ossoteoue or Osotouy was situated at the mouth of the Arkansas River. It is now thought to correspond to an archaeological site

An archaeological site is a place (or group of physical sites) in which evidence of past activity is preserved (either prehistoric or historic or contemporary), and which has been, or may be, investigated using the discipline of archaeology an ...

known as the Menard-Hodges Mounds.

In 1686 the French commander Henri de Tonti

Henri de Tonti (''né'' Enrico Tonti; – September 1704), also spelled Henri de Tonty, was an Italian-born French military officer, explorer, and ''voyageur'' who assisted René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, with North American explora ...

built a post near the mouth of the Arkansas River, which was later known as the Arkansas Post. This began European occupation of the Quapaw country. Tonti arranged for a resident Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

to be assigned there, but apparently without result. About 1697 a smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

epidemic

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics of infectious ...

killed the greater part of the women and children of two villages. In 1727 the Jesuits, from their house in New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, again took up the missionary work. In 1729 the Quapaw allied with French colonists against the Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Natchez Natchez may refer to:

Places

* Natchez, Alabama, United States

* Natchez, Indiana, United States

* Natchez, Louisiana, United States

* Natchez, Mississippi, a city in southwestern Mississippi, United States

* Grand Village of the Natchez, a site o ...

, resulting in the practical extermination of the Natchez tribe.

The French relocated the Arkansas Post upriver, trying to avoid flooding. After France lwas defeated by the British in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

, it ceded its North American territories to Britain. This nation exchanged some territory with Spain, which took over "control" of Arkansas and other former French territory west of the Mississippi River. The Spanish built new forts to protect its valued trading post with the Quapaw.

19th century

Shortly after the United States acquired the territory in 1803 by the

Shortly after the United States acquired the territory in 1803 by the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

, it recorded the Quapaw as living in three villages on the south side of the Arkansas River about above Arkansas Post. In 1818, the Quapaw made their first treaty with the US government, ceding all claims from the Red River to beyond the Arkansas and east of the Mississippi.

They kept a considerable tract between the Arkansas and the Saline, in the southeastern part of the state. Under continued US pressure, in 1824 they ceded this also, excepting occupied by the chief Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Pe ...

below Pine Bluff. They expected to incorporate with the Caddo of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, but were refused permission by the United States. Successive floods in the Caddo country near the Red River pushed many of the tribe toward starvation, and they wandered back to their old homes.

In 1834, under another treaty and the federal policy of Indian Removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a de ...

, the Quapaw were removed from the Mississippi valley areas to their present location in the northeast corner of Oklahoma, then Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

.

''Sarrasin'' (alternate spelling Saracen), their last chief before the removal, was a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

and friend of the Lazarist

, logo =

, image = Vincentians.png

, abbreviation = CM

, nickname = Vincentians, Paules, Lazarites, Lazarists, Lazarians

, established =

, founder = Vincent de Paul

, fou ...

missionaries (Congregation of the Missions), who had arrived in 1818. He died about 1830 and is buried adjoining St. Joseph's Church, Pine Bluff. A a memorial window in the church preserves his name. Fr. John M. Odin was the pioneer Lazarist missionary among the Quapaw; he later served as the Catholic Archbishop of New Orleans.

In 1824 the Jesuits of Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, under Father Charles Van Quickenborne, took up work among the native and migrant tribes of Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

(present-day Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

and Oklahoma). In 1846 the Mission of St. Francis was established among the Osage, on Neosho River

The Neosho River is a tributary of the Arkansas River in eastern Kansas and northeastern Oklahoma in the United States. Its tributaries also drain portions of Missouri and Arkansas. The river is about long.U.S. Geological Survey. National ...

, by Fathers John Shoenmakers and John Bax. They extended their services to the Quapaw for some years.

The Quapaw, together with associated remnant tribes, the Miami

Miami ( ), officially the City of Miami, known as "the 305", "The Magic City", and "Gateway to the Americas", is a East Coast of the United States, coastal metropolis and the County seat, county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade C ...

, Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

, Wyandot

Wyandot may refer to:

Native American ethnography

* Wyandot people, also known as the Huron

* Wyandot language

Wyandot (sometimes spelled Wandat) is the Iroquoian language traditionally spoken by the people known variously as Wyandot or Wya ...

and Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

, were served from the Mission of "Saint Mary of the Quapaws", at Quapaw, Oklahoma

Quapaw is a town in Ottawa County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 906 at the 2010 census, a 7.9 percent decline from the figure of 984 recorded in 2000. Quapaw is part of the Joplin, Missouri metropolitan area.

History

In 1891 Kan ...

. Historians estimated their number at European encounter as 5000. The ''Catholic Encyclopedia'' noted the people had suffered from high fatalities due to epidemics, wars, removals, and social disruption. It documented their numbers as 3200 in 1687, 1600 in 1750, 476 in 1843, and 307 in 1910, including people of mixed race

Mixed race people are people of more than one race or ethnicity. A variety of terms have been used both historically and presently for mixed race people in a variety of contexts, including ''multiethnic'', ''polyethnic'', occasionally ''bi-ethn ...

. The tribes had matrilineal kinship

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance o ...

systems, and children born to and raised by Quapaw women were considered to be tribal members.

Kinship, religion and culture

In addition to the four established divisions already noted, the Quapaw have the clan system, with a number of '' gentes''.Polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is married ...

was practiced by elite men, but was not common. They were agricultural. Their towns were palisaded. Their town houses, or public structures, are referred to as longhouses. They are constructed with timbers dovetailed together and bark roofs, and were commonly erected upon large man-made mounds to raise them above the frequent flooding in the lowlands along the rivers. Their ordinary houses were rectangular and long enough to accommodate several families.

The Quapaw dug large ditches, and constructed fish weir

A fishing weir, fish weir, fishgarth or kiddle is an obstruction placed in tidal waters, or wholly or partially across a river, to direct the passage of, or trap fish. A weir may be used to trap marine fish in the intertidal zone as the tide reced ...

s to manage their food supply. They excelled in pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and por ...

and in the painting of hide for bed covers and other purposes. The buried their dead in the ground, sometimes in earth mound

A mound is a heaped pile of earth, gravel, sand, rocks, or debris. Most commonly, mounds are earthen formations such as hills and mountains, particularly if they appear artificial. A mound may be any rounded area of topographically higher el ...

s or in the clay floors of their houses. The dead were frequently strapped to a stake in a sitting position and then covered with earth.

The Quapaw were friendly to the Europeans. They warred and competed with the Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classified as ...

and other Southeastern tribes over resources and trade.

20th century

In the early 20th century, an account noted that the Dhegiha language, a branch of Siouan including the "dialects" of the Omaha, Ponca, Osage, Kansa, and Quapaw, has received more extended study. Rev. J.O. Dorsey published material about it under the auspices of the

In the early 20th century, an account noted that the Dhegiha language, a branch of Siouan including the "dialects" of the Omaha, Ponca, Osage, Kansa, and Quapaw, has received more extended study. Rev. J.O. Dorsey published material about it under the auspices of the Bureau of American Ethnology

The Bureau of American Ethnology (or BAE, originally, Bureau of Ethnology) was established in 1879 by an act of Congress for the purpose of transferring archives, records and materials relating to the Indians of North America from the Interior D ...

, now part of the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

.

In popular culture

* The 2009 documentary '' Tar Creek,'' about theTar Creek Superfund Site

Tar Creek Superfund site is a United States Superfund site, declared in 1983, located in the cities of Picher and Cardin, Ottawa County, in northeastern Oklahoma. From 1900 to the 1960s lead mining and zinc mining companies left behind huge ope ...

located on Quapaw tribal lands, explored what at one time was considered to be the worst environmental disaster in the country. The film discusses the alleged racism of environmental and governmental practices that led to the neglect and lack of regulation that produced the hazards of this site. It is credited with causing the lead poisoning of a high percentage of children.

* In 2018, Infinite Productions produced a documentary titled ''The Pride of the Ogahpah'', about the development of the Downstream Casino Resort, which is operated by The Quapaw Nation.

* The USS Quapaw (ATF-110)

USS ''Quapaw'' (ATF–110/AT-110) was a in the United States Navy. She was named after the Quapaw.

''Quapaw'' was laid down by United Engineering Co., Alameda, California, 28 December 1942; launched 15 May 1943; sponsored by Mrs. N. Lehman; ...

, a fleet ocean tug commissioned 6 May 1944, was named for the Quapaw people.

Notable Quapaw

*Louis Ballard

Louis W. Ballard (July 8, 1931 – February 9, 2007) was a Native American composer, educator, author, artist, and journalist. He is "known as the father of Native American composition."

Early life

Louis Wayne Ballard was born on July 8, 1931, ...

, (1931–2007) composer, artist, and educator

* Victor Griffin ( 1873–1958), chief, interpreter, and peyote roadman

* Barbara Kyser-Collier, tribal governmental figure

* Ardina Moore

Ardina Moore (née Revard, December 1, 1930 – April 19, 2022) was a Quapaw/ Osage Native American from Miami, Oklahoma. A fluent Quapaw language speaker, she developed a language preservation program and taught the language to younger tribal m ...

, language teacher, regalia maker/textile artist

* Saracen

upright 1.5, Late 15th-century German woodcut depicting Saracens

Saracen ( ) was a term used in the early centuries, both in Greek and Latin writings, to refer to the people who lived in and near what was designated by the Romans as Arabia Pe ...

, last traditional chief and recipient of a presidential medal

* Tall Chief

Tall Chief (ca. 1840-1918) was a hereditary chief of the Quapaw Tribe and a peyote roadman. He served in this position after his father, Lame Chief, died in 1874, until his own death in 1918 at around 78 years old.

Tall Chief was the last indiv ...

( 1840–1918), chief, peyote roadman

See also

*Quapaw Indian Agency The Quapaw Indian Agency was a territory that included parts of the present-day Oklahoma counties of Ottawa and Delaware. Established in the late 1830s as part of lands allocated to the Cherokee Nation, this area was later leased by the federal g ...

* List of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition

This is a list of sites and peoples visited by the Hernando de Soto Expedition in the years 1539–1543. In May 1539, de Soto left Havana, Cuba, with nine ships, over 620 men and 220 surviving horses and landed at Charlotte Harbor, Florida. This ...

* Mitchigamea Mitchigamea or Michigamea or Michigamie were a tribe in the Illinois Confederation. Not much is known about them and their origin is uncertain. Originally they were said to be from Lake Michigan, perhaps the Chicago area. Mitchie Precinct, Monroe C ...

Notes

External links

Quapaw Tribe

official website

Quapaw Tribal Ancestry

official tribal sanctioned site with genealogy information, pictures, and stories

official tribal sanctioned site with language information, words, audio clips, and source information

Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

EPA

Access Genealogy

Tar Creek

Tar Creek documentary website {{DEFAULTSORT:Quapaw Dhegiha Siouan peoples Federally recognized tribes in the United States American Indian reservations in Oklahoma Native American tribes in Arkansas Native American tribes in Oklahoma