Evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary thought, the recognition that

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriat ...

change over time and the perceived understanding of how such processes work, has roots in antiquity—in the ideas of the

ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

,

Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

,

Chinese,

Church Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

as well as in

medieval Islamic science. With the beginnings of modern

biological taxonomy

In biology, taxonomy () is the scientific study of naming, defining ( circumscribing) and classifying groups of biological organisms based on shared characteristics. Organisms are grouped into taxa (singular: taxon) and these groups are given ...

in the late 17th century, two opposed ideas influenced

Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

biological thinking:

essentialism

Essentialism is the view that objects have a set of attributes that are necessary to their identity. In early Western thought, Plato's idealism held that all things have such an "essence"—an "idea" or "form". In ''Categories'', Aristotle sim ...

, the belief that every species has essential characteristics that are unalterable, a concept which had developed from

medieval Aristotelian metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

, and that fit well with

natural theology

Natural theology, once also termed physico-theology, is a type of theology that seeks to provide arguments for theological topics (such as the existence of a deity) based on reason and the discoveries of science.

This distinguishes it from ...

; and the development of the new anti-Aristotelian approach to

modern science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal.

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesop ...

: as the

Enlightenment progressed, evolutionary

cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

and the

mechanical philosophy

The mechanical philosophy is a form of natural philosophy which compares the universe to a large-scale mechanism (i.e. a machine). The mechanical philosophy is associated with the scientific revolution of early modern Europe. One of the first expo ...

spread from the

physical sciences

Physical science is a branch of natural science that studies non-living systems, in contrast to life science. It in turn has many branches, each referred to as a "physical science", together called the "physical sciences".

Definition

Phy ...

to

natural history.

Naturalists began to focus on the variability of species; the emergence of

palaeontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

with the concept of

extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the Endling, last individual of the species, although the Functional ext ...

further undermined static views of

nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans are ...

. In the early 19th century prior to

Darwinism

Darwinism is a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of small, inherited variations tha ...

,

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biolo ...

(1744–1829) proposed his

theory

A theory is a rational type of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the results of such thinking. The process of contemplative and rational thinking is often associated with such processes as observational study or research. Theories may ...

of the

transmutation of species

Transmutation of species and transformism are unproven 18th and 19th-century evolutionary ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a term used ...

, the first fully formed theory of

evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

.

In 1858

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended ...

and

Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British natural history, naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution thro ...

published a new evolutionary theory, explained in detail in Darwin's ''

On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'' (1859). Darwin's theory, originally called descent with modification is known contemporarily as Darwinism or Darwinian theory. Unlike Lamarck, Darwin proposed

common descent

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. All living beings are in fact descendants of a unique ancestor commonly referred to as the last universal com ...

and a branching

tree of life

The tree of life is a fundamental archetype in many of the world's mythological, religious, and philosophical traditions. It is closely related to the concept of the sacred tree.Giovino, Mariana (2007). ''The Assyrian Sacred Tree: A Hist ...

, meaning that two very different species could share a common ancestor. Darwin based his theory on the idea of

natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

: it synthesized a broad range of evidence from

animal husbandry

Animal husbandry is the branch of agriculture concerned with animals that are raised for meat, fibre, milk, or other products. It includes day-to-day care, selective breeding, and the raising of livestock. Husbandry has a long history, starti ...

,

biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, ...

,

geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other Astronomical object, astronomical objects, the features or rock (geology), rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology ...

,

morphology, and

embryology

Embryology (from Greek ἔμβρυον, ''embryon'', "the unborn, embryo"; and -λογία, '' -logia'') is the branch of animal biology that studies the prenatal development of gametes (sex cells), fertilization, and development of embr ...

. Debate over Darwin's work led to the rapid acceptance of the general concept of evolution, but the specific mechanism he proposed, natural selection, was not widely accepted until it was revived by developments in

biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary ...

that occurred during the 1920s through the 1940s. Before that time most

biologist

A biologist is a scientist who conducts research in biology. Biologists are interested in studying life on Earth, whether it is an individual cell, a multicellular organism, or a community of interacting populations. They usually specialize ...

s regarded other factors as responsible for evolution.

Alternatives to natural selection suggested during "

the eclipse of Darwinism

Julian Huxley used the phrase "the eclipse of Darwinism" to describe the state of affairs prior to what he called the "modern synthesis". During the "eclipse", evolution was widely accepted in scientific circles but relatively few biologists be ...

" (c. 1880 to 1920) included

inheritance of acquired characteristics

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

(

neo-Lamarckism

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

), an innate drive for change (

orthogenesis

Orthogenesis, also known as orthogenetic evolution, progressive evolution, evolutionary progress, or progressionism, is an obsolete biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolve in a definite direction towards some g ...

), and sudden large

mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, m ...

s (

saltationism).

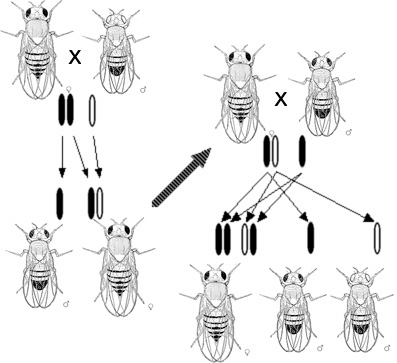

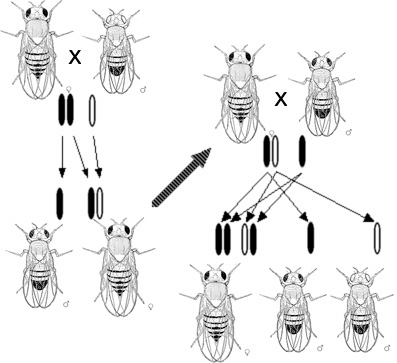

Mendelian genetics

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later populari ...

, a series of 19th-century experiments with

pea

The pea is most commonly the small spherical seed or the seed-pod of the flowering plant species ''Pisum sativum''. Each pod contains several peas, which can be green or yellow. Botanically, pea pods are fruit, since they contain seeds and d ...

plant variations rediscovered in 1900, was integrated with natural selection by

Ronald Fisher

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher (17 February 1890 – 29 July 1962) was a British polymath who was active as a mathematician, statistician, biologist, geneticist, and academic. For his work in statistics, he has been described as "a genius who ...

,

J. B. S. Haldane

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (; 5 November 18921 December 1964), nicknamed "Jack" or "JBS", was a British-Indian scientist who worked in physiology, genetics, evolutionary biology, and mathematics. With innovative use of statistics in biolo ...

, and

Sewall Wright

Sewall Green Wright FRS(For) Honorary FRSE (December 21, 1889March 3, 1988) was an American geneticist known for his influential work on evolutionary theory and also for his work on path analysis. He was a founder of population genetics alongsi ...

during the 1910s to 1930s, and resulted in the founding of the new discipline of

population genetics

Population genetics is a subfield of genetics that deals with genetic differences within and between populations, and is a part of evolutionary biology. Studies in this branch of biology examine such phenomena as adaptation, speciation, and po ...

. During the 1930s and 1940s population genetics became integrated with other biological fields, resulting in a widely applicable theory of evolution that encompassed much of biology—the

modern synthesis

Modern synthesis or modern evolutionary synthesis refers to several perspectives on evolutionary biology, namely:

* Modern synthesis (20th century), the term coined by Julian Huxley in 1942 to denote the synthesis between Mendelian genetics and ...

.

Following the establishment of

evolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes (natural selection, common descent, speciation) that produced the diversity of life on Earth. It is also defined as the study of the history of life ...

, studies of mutation and

genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species, it ranges widely from the number of species to differences within species and can be attributed to the span of survival for a species. It is dis ...

in natural populations, combined with biogeography and

systematics

Biological systematics is the study of the diversification of living forms, both past and present, and the relationships among living things through time. Relationships are visualized as evolutionary trees (synonyms: cladograms, phylogenetic t ...

, led to sophisticated mathematical and causal models of evolution. Palaeontology and

comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in ...

allowed more detailed reconstructions of the

evolutionary history of life

The history of life on Earth traces the processes by which living and fossil organisms evolved, from the earliest emergence of life to present day. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago (abbreviated as ''Ga'', for ''gigaannum'') and evide ...

. After the rise of

molecular genetics

Molecular genetics is a sub-field of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the ...

in the 1950s, the field of

molecular evolution

Molecular evolution is the process of change in the sequence composition of cellular molecules such as DNA, RNA, and proteins across generations. The field of molecular evolution uses principles of evolutionary biology and population genet ...

developed, based on

protein sequences and immunological tests, and later incorporating

RNA and

DNA studies. The

gene-centred view of evolution rose to prominence in the 1960s, followed by the

neutral theory of molecular evolution

The neutral theory of molecular evolution holds that most evolutionary changes occur at the molecular level, and most of the variation within and between species are due to random genetic drift of mutant alleles that are selectively neutral. The ...

, sparking debates over

adaptationism

Adaptationism (also known as functionalism) is the Darwinian view that many physical and psychological traits of organisms are evolved adaptations. Pan-adaptationism is the strong form of this, deriving from the early 20th century modern synthesi ...

, the

unit of selection

A unit of selection is a biological entity within the hierarchy of biological organization (for example, an entity such as: a self-replicating molecule, a gene, a cell, an organism, a group, or a species) that is subject to natural selection. ...

, and the relative importance of

genetic drift

Genetic drift, also known as allelic drift or the Wright effect, is the change in the frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random chance.

Genetic drift may cause gene variants to disappear completely and there ...

versus natural selection as causes of evolution. In the late 20th-century, DNA sequencing led to

molecular phylogenetics

Molecular phylogenetics () is the branch of phylogeny that analyzes genetic, hereditary molecular differences, predominantly in DNA sequences, to gain information on an organism's evolutionary relationships. From these analyses, it is possible to ...

and the reorganization of the tree of life into the

three-domain system

The three-domain system is a biological classification introduced by Carl Woese, Otto Kandler, and Mark Wheelis in 1990 that divides cellular life forms into three domains, namely Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukaryota or Eukarya. The key difference ...

by

Carl Woese

Carl Richard Woese (; July 15, 1928 – December 30, 2012) was an American microbiologist and biophysicist. Woese is famous for defining the Archaea (a new domain of life) in 1977 through a pioneering phylogenetic taxonomy of 16S ribosomal RNA, ...

. In addition, the newly recognized factors of

symbiogenesis

Symbiogenesis (endosymbiotic theory, or serial endosymbiotic theory,) is the leading evolutionary theory of the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic organisms. The theory holds that mitochondria, plastids such as chloroplasts, and pos ...

and

horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). H ...

introduced yet more complexity into evolutionary theory. Discoveries in evolutionary biology have made a significant impact not just within the traditional branches of biology, but also in other academic disciplines (for example:

anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of be ...

and

psychology

Psychology is the science, scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immens ...

) and on society at large.

[ and ]

Antiquity

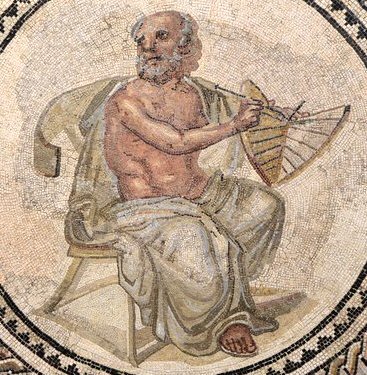

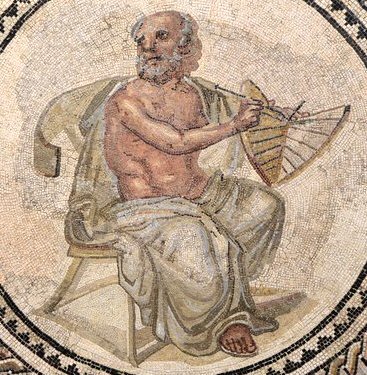

Greeks

Proposals that one type of

animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and go through an ontogenetic stage ...

, even

human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, cultu ...

s, could descend from other types of animals, are known to go back to the first

pre-Socratic Greek philosophers

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

.

Anaximander of Miletus (c. 610—546 BC) proposed that the first animals lived in water, during a wet phase of the

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's sur ...

's past, and that the first land-dwelling ancestors of mankind must have been born in water, and only spent part of their life on land. He also argued that the first human of the form known today must have been the child of a different type of animal (probably a fish), because man needs prolonged nursing to live.

In the late nineteenth century, Anaximander was hailed as the "first Darwinist", but this characterization is no longer commonly agreed.

Anaximander's hypothesis could be considered "evolution" in a sense, although not a Darwinian one.

Empedocles

Empedocles (; grc-gre, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; , 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the ...

(c. 490—430 BC), argued that what we call birth and death in animals are just the mingling and separations of elements which cause the countless "tribes of mortal things." Specifically, the first animals and

plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae excl ...

s were like disjointed parts of the ones we see today, some of which survived by joining in different combinations, and then intermixing during the development of the embryo, and where "everything turned out as it would have if it were on purpose, there the creatures survived, being accidentally compounded in a suitable way."

Other philosophers who became more influential at that time, including

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

(c. 428/427—348/347 BC),

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

(384—322 BC), and members of the

Stoic school of philosophy, believed that the types of all things, not only living things, were fixed by divine design.

Plato was called by biologist

Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr (; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists. He was also a renowned taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, philosopher of biology, and historian of science. His ...

"the great antihero of evolutionism,"

because he promoted belief in essentialism, which is also referred to as the

theory of Forms

The theory of Forms or theory of Ideas is a philosophical theory, fuzzy concept, or world-view, attributed to Plato, that the physical world is not as real or true as timeless, absolute, unchangeable ideas. According to this theory, ideas in th ...

. This theory holds that each natural type of object in the observed world is an imperfect manifestation of the ideal, form or "species" which defines that type. In his ''

Timaeus'' for example, Plato has a character tell a story that the

Demiurge

In the Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic schools of philosophy, the demiurge () is an artisan-like figure responsible for fashioning and maintaining the physical universe. The Gnostics adopted the term ''demiurge'' ...

created the

cosmos

The cosmos (, ) is another name for the Universe. Using the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos, and understandings of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in ...

and everything in it because, being good, and hence, "... free from jealousy, He desired that all things should be as like Himself as they could be." The creator created all conceivable forms of life, since "... without them the

universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the univers ...

will be incomplete, for it will not contain every kind of animal which it ought to contain, if it is to be perfect." This "

principle of plenitude"—the idea that all potential forms of life are essential to a perfect creation—greatly influenced

Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

thought.

However some historians of science have questioned how much influence Plato's essentialism had on natural philosophy by stating that many philosophers after Plato believed that species might be capable of transformation and that the idea that biologic species were fixed and possessed unchangeable essential characteristics did not become important until the beginning of biological taxonomy in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Aristotle, the most influential of the Greek philosophers in

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, was a student of Plato and is also the earliest natural historian whose work has been preserved in any real detail.

His writings on biology resulted from his research into natural history on and around the island of

Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( el, Λέσβος, Lésvos ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece. It is separated from Asia Minor by the nar ...

, and have survived in the form of four books, usually known by their

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

names, ''

De anima

''On the Soul'' ( Greek: , ''Peri Psychēs''; Latin: ''De Anima'') is a major treatise written by Aristotle c. 350 BC. His discussion centres on the kinds of souls possessed by different kinds of living things, distinguished by their differen ...

'' (''On the Soul''), ''

Historia animalium

''History of Animals'' ( grc-gre, Τῶν περὶ τὰ ζῷα ἱστοριῶν, ''Ton peri ta zoia historion'', "Inquiries on Animals"; la, Historia Animalium, "History of Animals") is one of the major texts on biology by the ancient Gr ...

'' (''History of Animals''), ''

De generatione animalium

The ''Generation of Animals'' (or ''On the Generation of Animals''; Greek: ''Περὶ ζῴων γενέσεως'' (''Peri Zoion Geneseos''); Latin: ''De Generatione Animalium'') is one of the biological works of the Corpus Aristotelicum, the col ...

'' (''Generation of Animals''), and ''

De partibus animalium'' (''On the Parts of Animals''). Aristotle's works contain accurate observations, fitted into his own theories of the body's mechanisms.

However, for

Charles Singer, "Nothing is more remarkable than

ristotle'sefforts to

xhibit

Exhibit may refer to:

*Exhibit (legal), evidence in physical form brought before the court

**Demonstrative evidence, exhibits and other physical forms of evidence used in court to demonstrate, show, depict, inform or teach relevant information to ...

the relationships of living things as a ''scala naturae''."

This ''

scala naturae'', described in ''Historia animalium'', classified organisms in relation to a hierarchical but static "Ladder of Life" or "great chain of being," placing them according to their complexity of structure and function, with organisms that showed greater vitality and ability to move described as "higher organisms."

Aristotle believed that features of living organisms showed clearly that they had what he called a

final cause

The four causes or four explanations are, in Aristotelian thought, four fundamental types of answer to the question "why?", in analysis of change or movement in nature: the material, the formal, the efficient, and the final. Aristotle wrote th ...

, that is to say that their form suited their function.

He explicitly rejected the view of Empedocles that living creatures might have originated by chance.

Other Greek philosophers, such as

Zeno of Citium

Zeno of Citium (; grc-x-koine, Ζήνων ὁ Κιτιεύς, ; c. 334 – c. 262 BC) was a Hellenistic philosopher from Citium (, ), Cyprus. Zeno was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy, which he taught in Athens from about 300 B ...

(334—262 BC) the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy, agreed with Aristotle and other earlier philosophers that nature showed clear evidence of being designed for a purpose; this view is known as

teleology

Teleology (from and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology" In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

.

The Roman

Skeptic

Skepticism, also spelled scepticism, is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the ...

philosopher

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

(106—43 BC) wrote that Zeno was known to have held the view, central to Stoic physics, that nature is primarily "directed and concentrated...to secure for the world...the structure best fitted for survival."

Chinese

Ancient

Chinese thinkers such as

Zhuang Zhou

Zhuang Zhou (), commonly known as Zhuangzi (; ; literally "Master Zhuang"; also rendered in the Wade–Giles romanization as Chuang Tzu), was an influential Chinese philosopher who lived around the 4th century BCE during the Warring State ...

(c. 369—286 BC), a

Taoist

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmony with the '' Tao ...

philosopher, expressed ideas on changing biological species. According to

Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, i ...

, Taoism explicitly denies the fixity of biological species and Taoist philosophers speculated that species had developed differing attributes in response to differing environments.

Taoism regards humans, nature and the heavens as existing in a state of "constant transformation" known as the ''

Tao'', in contrast with the more static view of nature typical of Western thought.

Roman Empire

Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; – ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem '' De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into E ...

' poem ''

De rerum natura

''De rerum natura'' (; ''On the Nature of Things'') is a first-century BC didactic poem by the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius ( – c. 55 BC) with the goal of explaining Epicurean philosophy to a Roman audience. The poem, written in some ...

'' provides the best surviving explanation of the ideas of the Greek Epicurean philosophers. It describes the development of the cosmos, the Earth, living things, and human society through purely naturalistic mechanisms, without any reference to

supernatural

Supernatural refers to phenomena or entities that are beyond the laws of nature. The term is derived from Medieval Latin , from Latin (above, beyond, or outside of) + (nature) Though the corollary term "nature", has had multiple meanings si ...

involvement. ''De rerum natura'' would influence the cosmological and evolutionary speculations of philosophers and scientists during and after the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

.

This view was in strong contrast with the views of Roman philosophers of the Stoic school such as

Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (; 65 AD), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and, in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca was born ...

(c. 4 BC – AD 65), and

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

(23—79 AD) who had a strongly teleological view of the natural world that influenced

Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology of Christian belief and practice. Such study concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Christian tradition. Christian theologians use biblical exeg ...

.

[ Cicero reports that the peripatetic and Stoic view of nature as an agency concerned most basically with producing life "best fitted for survival" was taken for granted among the ]Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

elite.

Early Church Fathers

Origen of Alexandria

In line with earlier Greek thought, the third-century Christian philosopher and Church Father

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical pe ...

Origen of Alexandria

Origen of Alexandria, ''Ōrigénēs''; Origen's Greek name ''Ōrigénēs'' () probably means "child of Horus" (from , "Horus", and , "born"). ( 185 – 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an early Christian scholar, ascetic, and the ...

argued that the creation story in the Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek ; Hebrew: בְּרֵאשִׁית ''Bəreʾšīt'', "In hebeginning") is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its first word, ( "In the beginning" ...

should be interpreted as an allegory for the falling of human souls away from the glory of the divine, and not as a literal, historical account:

Gregory of Nyssa

Gregory of Nyssa

Gregory of Nyssa, also known as Gregory Nyssen ( grc-gre, Γρηγόριος Νύσσης; c. 335 – c. 395), was Bishop of Nyssa in Cappadocia from 372 to 376 and from 378 until his death in 395. He is venerated as a saint in Catholicis ...

wrote:Scripture informs us that the Deity proceeded by a sort of graduated and ordered advance to the creation of man. After the foundations of the universe were laid, as the history records, man did not appear on the earth at once, but the creation of the brutes preceded him, and the plants preceded them. Thereby Scripture shows that the vital forces blended with the world of matter according to a gradation; first it infused itself into insensate nature; and in continuation of this advanced into the sentient world; and then ascended to intelligent and rational beings (emphasis added).

Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was the president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years and a cofounder of the American Euge ...

wrote in his work on the history of evolutionary thought, ''From the Greeks to Darwin'' (1894):

Among the Christian Fathers the movement towards a partly naturalistic interpretation of the order of Creation was made by Gregory of Nyssa

Gregory of Nyssa, also known as Gregory Nyssen ( grc-gre, Γρηγόριος Νύσσης; c. 335 – c. 395), was Bishop of Nyssa in Cappadocia from 372 to 376 and from 378 until his death in 395. He is venerated as a saint in Catholicis ...

in the fourth century, and was completed by Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

in the fourth and fifth centuries. ... regory of Nyssataught that Creation was potential. God imparted to matter its fundamental properties and laws. The objects and completed forms of the Universe developed gradually out of chaotic material.

Augustine of Hippo

In the fourth century AD, the bishop and theologian

In the fourth century AD, the bishop and theologian Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

followed Origen in arguing that the Genesis creation story should be read allegorically. In his book ''De Genesi ad Litteram'' (''On the Literal Meaning of Genesis'') he prefaces saying,In all sacred books, we should consider the eternal truths that are taught, the facts that are narrated, the future events that are predicted, and the precepts or counsels that are given. In the case of a narrative of events, the question arises whether everything must be taken according to the figurative sense only, or whether it must be expounded and defended also as a faithful record of what happened. No Christian would dare say that the narrative must not be taken in a figurative sense. For St. Paul says: ''Now all these things that happened to them were symbolic.'' Cor 10:11And he explains the statement in Genesis, ''And they shall be two in one flesh'', as a great mystery in reference to Christ and to the Church. ph 5:32ref name=":1" />

Later he differentiates between the days of the Genesis 1 creation narrative and 24 hour daysBut at least we know he days of creationare different from the ordinary day of which we are familiar

He also talks about a form of theistic evolutionThe things odhad potentially created... ameforth in the course of time on different days according to their different kinds... ndthe rest of the earth asfilled with its various kinds of creatures, hich

Ij ( fa, ايج, also Romanized as Īj; also known as Hich and Īch) is a village in Golabar Rural District, in the Central District of Ijrud County, Zanjan Province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also ...

produced their appropriate forms in due time.

Which has led Francis Collins

Francis Sellers Collins (born April 14, 1950) is an American physician-geneticist who discovered the genes associated with a number of diseases and led the Human Genome Project. He is the former director of the National Institutes of Health (N ...

of Biologos

The BioLogos Foundation is a Christian advocacy group that supports the view that God created the world using evolution of different species as the mechanism. It was established by Francis Collins in 2007 after receiving letters and emails from ...

to believe Augustine espoused a form of theistic evolution.idea

In common usage and in philosophy, ideas are the results of thought. Also in philosophy, ideas can also be mental representational images of some object. Many philosophers have considered ideas to be a fundamental ontological category of bei ...

"that forms of life had been transformed 'slowly over time prompted Father Giuseppe Tanzella-Nitti, Professor of Theology at the Pontifical Santa Croce University in Rome, to claim that Augustine had suggested a form of evolution.

Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was the president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 years and a cofounder of the American Euge ...

wrote in ''From the Greeks to Darwin'' (1894):

In '''' (1896), Andrew Dickson White

Andrew Dickson White (November 7, 1832 – November 4, 1918) was an American historian and educator who cofounded Cornell University and served as its first president for nearly two decades. He was known for expanding the scope of college curricu ...

wrote about Augustine's attempts to preserve the ancient evolutionary approach to the creation as follows:

In Augustine's ''De Genesi contra Manichæos'', on Genesis he says: "To suppose that God formed man from the dust with bodily hands is very childish. ...God neither formed man with bodily hands nor did he breathe upon him with throat and lips." Augustine suggests in other work his theory of the later development of insects out of carrion, and the adoption of the old emanation or evolution theory, showing that "certain very small animals may not have been created on the fifth and sixth days, but may have originated later from putrefying matter." Concerning Augustine's ''De Trinitate

''On the Trinity'' ( la, De Trinitate) is a Latin book written by Augustine of Hippo to discuss the Trinity in context of the logos. Although not as well known as some of his other works, some scholars have seen it as his masterpiece, of more doc ...

'' (''On the Trinity''), White wrote that Augustine "...develops at length the view that in the creation of living beings there was something like a growth—that God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

is the ultimate author, but works through secondary causes; and finally argues that certain substances are endowed by God with the power of producing certain classes of plants and animals."

Augustine believed, that whatever science shows us the Bible must teach since the Bible is infallibleUsually, even a non-Christian knows something about the earth, the heavens, and the other elements of this world, about the motion and orbit of the stars ... Now, it is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for an infidel to hear a Christian, presumably giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking non-sense on these topics; and we should take all means to prevent such an embarrassing situation, in which people show up vast ignorance in a Christian and laugh it to scorn. The shame is not so much that an ignorant individual is derided, but that people outside the household of the faith think our sacred writers held such opinions, and, to the great loss of those for whose salvation we toil, the writers of our Scripture are criticized and rejected as unlearned men.

Middle Ages

Islamic philosophy and the struggle for existence

Although Greek and Roman evolutionary ideas died out in Western Europe after the fall of the

Although Greek and Roman evolutionary ideas died out in Western Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

, they were not lost to Islamic philosophers

Muslim philosophers both profess Islam and engage in a style of philosophy situated within the structure of the Arabic language and Islam, though not necessarily concerned with religious issues. The sayings of the companions of Muhammad contained ...

and scientists

A scientist is a person who conducts scientific research to advance knowledge in an area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engaged in the philosophi ...

(nor to the culturally Greek Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

). In the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

of the 8th to the 13th centuries, philosophers explored ideas about natural history. These ideas included transmutation from non-living to living: "from mineral to plant, from plant to animal, and from animal to man."Conway Zirkle

Conway Zirkle (October 28, 1895 – March 28, 1972) was an American botanist and historian of science.

Zirkle was professor emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania. He was highly critical of Lamarckism, Lysenkoism and Marxian biology.Joravsk ...

, writing about the history of natural selection in 1941, said that an excerpt from this work was the only relevant passage he had found from an Arabian scholar. He provided a quotation describing the struggle for existence, citing a Spanish translation of this work: "Every weak animal devours those weaker than itself. Strong animals cannot escape being devoured by other animals stronger than they. And in this respect, men do not differ from animals, some with respect to others, although they do not arrive at the same extremes. In short, God has disposed some human beings as a cause of life for others, and likewise, he has disposed the latter as a cause of the death of the former."food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web starting from producer organisms (such as grass or algae which produce their own food via photosynthesis) and ending at an apex predator species (like grizzly bears or killer whales), de ...

s.

Some of Ibn Khaldūn's thoughts, according to some commentators, anticipate the biological theory of evolution.Muqaddimah

The ''Muqaddimah'', also known as the ''Muqaddimah of Ibn Khaldun'' ( ar, مقدّمة ابن خلدون) or ''Ibn Khaldun's Prolegomena'' ( grc, Προλεγόμενα), is a book written by the Arab historian Ibn Khaldun in 1377 which records ...

'' in which he asserted that humans developed from "the world of the monkeys," in a process by which "species become more numerous".

Christian philosophy

Thomas Aquinas on creation and natural processes

While most Christian theologians held that the natural world was part of an unchanging designed hierarchy, some theologians speculated that the world might have developed through natural processes. Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, Dominican Order, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino, Italy, Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest who was an influential List of Catholic philo ...

expounded on Augustine of Hippo's early idea of theistic evolution

Theistic evolution (also known as theistic evolutionism or God-guided evolution) is a theological view that God creates through laws of nature. Its religious teachings are fully compatible with the findings of modern science, including biologica ...

On the day on which God created the heaven and the earth, He created also every plant of the field, not, indeed, actually, but 'before it sprung up in the earth,' that is, potentially... All things were not distinguished and adorned together, not from a want of power on God's part, as requiring time in which to work, but that due order might be observed in the instituting of the world.

He saw that the autonomy of nature was a sign of God's goodness, and detected no conflict between a divinely created universe and the idea that the universe had developed over time through natural mechanisms. However, Aquinas disputed the views of those (like the ancient Greek philosopher Empedocles) who held that such natural processes showed that the universe could have developed without an underlying purpose. Aquinas rather held that: "Hence, it is clear that nature is nothing but a certain kind of art, i.e., the divine art, impressed upon things, by which these things are moved to a determinate end. It is as if the shipbuilder were able to give to timbers that by which they would move themselves to take the form of a ship."

Renaissance and Enlightenment

In the first half of the 17th century,

In the first half of the 17th century, René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Ma ...

' mechanical philosophy

The mechanical philosophy is a form of natural philosophy which compares the universe to a large-scale mechanism (i.e. a machine). The mechanical philosophy is associated with the scientific revolution of early modern Europe. One of the first expo ...

encouraged the use of the metaphor of the universe as a machine, a concept that would come to characterise the scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transforme ...

. Between 1650 and 1800, some naturalists, such as Benoît de Maillet

Benoît de Maillet (Saint-Mihiel, 12 April 1656 – Marseille, 30 January 1738) was a well-travelled French diplomat and natural historian. He was French consul general at Cairo, and overseer in the Levant. He formulated an evolutionary hypothesi ...

, produced theories that maintained that the universe, the Earth, and life, had developed mechanically, without divine guidance. In contrast, most contemporary theories of evolution, such of those of Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathem ...

and Johann Gottfried Herder

Johann Gottfried von Herder ( , ; 25 August 174418 December 1803) was a German philosopher, theologian, poet, and literary critic. He is associated with the Enlightenment, '' Sturm und Drang'', and Weimar Classicism.

Biography

Born in Mohr ...

, regarded evolution as a fundamentally process. In 1751, Pierre Louis Maupertuis

Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (; ; 1698 – 27 July 1759) was a French mathematician, philosopher and man of letters. He became the Director of the Académie des Sciences, and the first President of the Prussian Academy of Science, at the ...

veered toward more materialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materiali ...

ground. He wrote of natural modifications occurring during reproduction and accumulating over the course of many generations, producing races and even new species, a description that anticipated in general terms the concept of natural selection.

Maupertuis' ideas were in opposition to the influence of early taxonomists like John Ray

John Ray FRS (29 November 1627 – 17 January 1705) was a Christian English naturalist widely regarded as one of the earliest of the English parson-naturalists. Until 1670, he wrote his name as John Wray. From then on, he used 'Ray', after ...

. In the late 17th century, Ray had given the first formal definition of a biological species, which he described as being characterized by essential unchanging features, and stated the seed of one species could never give rise to another.embryological development

Prenatal development () includes the development of the embryo and of the fetus during a viviparous animal's gestation. Prenatal development starts with fertilization, in the germinal stage of embryonic development, and continues in fetal devel ...

; its first use in relation to development of species came in 1762, when Charles Bonnet

Charles Bonnet (; 13 March 1720 – 20 May 1793) was a Genevan naturalist and philosophical writer. He is responsible for coining the term ''phyllotaxis'' to describe the arrangement of leaves on a plant. He was among the first to notice parth ...

used it for his concept of " pre-formation," in which females carried a miniature form of all future generations. The term gradually gained a more general meaning of growth or progressive development.French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

philosopher Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (; 7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) was a French naturalist, mathematician, cosmologist, and encyclopédiste.

His works influenced the next two generations of naturalists, including two prominent ...

, one of the leading naturalists of the time, suggested that what most people referred to as species were really just well-marked varieties, modified from an original form by environmental factors. For example, he believed that lions, tigers, leopards, and house cats might all have a common ancestor. He further speculated that the 200 or so species of mammals then known might have descended from as few as 38 original animal forms. Buffon's evolutionary ideas were limited; he believed each of the original forms had arisen through spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from nonliving matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could arise f ...

and that each was shaped by "internal moulds" that limited the amount of change. Buffon's works, ''Histoire naturelle'' (1749–1789) and ''Époques de la nature'' (1778), containing well-developed theories about a completely materialistic origin for the Earth and his ideas questioning the fixity of species, were extremely influential. Another French philosopher, Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the '' Encyclopédie'' along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a promi ...

, also wrote that living things might have first arisen through spontaneous generation, and that species were always changing through a constant process of experiment where new forms arose and survived or not based on trial and error; an idea that can be considered a partial anticipation of natural selection. Between 1767 and 1792, James Burnett, Lord Monboddo

James Burnett, Lord Monboddo (baptised 25 October 1714; died 26 May 1799) was a Scottish judge, scholar of linguistic evolution, philosopher and deist. He is most famous today as a founder of modern comparative historical linguistics. In 176 ...

, included in his writings not only the concept that man had descended from primates, but also that, in response to the environment, creatures had found methods of transforming their characteristics over long time intervals. Charles Darwin's grandfather, Erasmus Darwin

Erasmus Robert Darwin (12 December 173118 April 1802) was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, and poet.

His poems ...

, published ''Zoonomia

''Zoonomia; or the Laws of Organic Life'' (1794-96) is a two-volume medical work by Erasmus Darwin dealing with pathology, anatomy, psychology, and the functioning of the body. Its primary framework is one of associationist psychophysiology. Th ...

'' (1794–1796) which suggested that "all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament." In his poem ''Temple of Nature'' (1803), he described the rise of life from minute organisms living in mud to all of its modern diversity.

Early 19th century

Paleontology and geology

In 1796, Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier was a major figure in na ...

published his findings on the differences between living elephant

Elephants are the largest existing land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant. They are the only surviving members of the family Elephantida ...

s and those found in the fossil record

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

. His analysis identified mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus'', one of the many genera that make up the order of trunked mammals called proboscideans. The various species of mammoth were commonly equipped with long, curved tusks an ...

s and mastodon

A mastodon ( 'breast' + 'tooth') is any proboscidean belonging to the extinct genus ''Mammut'' (family Mammutidae). Mastodons inhabited North and Central America during the late Miocene or late Pliocene up to their extinction at the end of the ...

s as distinct species, different from any living animal, and effectively ended a long-running debate over whether a species could become extinct. In 1788, James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June O.S.172614 June 1726 New Style. – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, agriculturalist, chemical manufacturer, naturalist and physician. Often referred to as the father of modern geology, he played a key role ...

described gradual

The gradual ( la, graduale or ) is a chant or hymn in the Mass, the liturgical celebration of the Eucharist in the Catholic Church, and among some other Christians. It gets its name from the Latin (meaning "step") because it was once chanted ...

geological processes operating continuously over deep time

Deep time is a term introduced and applied by John McPhee to the concept of geologic time in his book ''Basin and Range'' (1981), parts of which originally appeared in the '' New Yorker'' magazine.

The philosophical concept of geological time ...

.[: "...we find no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end."] In the 1790s, William Smith began the process of ordering rock strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as e ...

by examining fossils in the layers while he worked on his geologic map of England. Independently, in 1811, Cuvier and Alexandre Brongniart

Alexandre Brongniart (5 February 17707 October 1847) was a French chemist, mineralogist, geologist, paleontologist, and zoologist, who collaborated with Georges Cuvier on a study of the geology of the region around Paris. Observing fossil content ...

published an influential study of the geologic history of the region around Paris, based on the stratigraphic

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers (strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithostra ...

succession of rock layers. These works helped establish the antiquity of the Earth. Cuvier advocated catastrophism

In geology, catastrophism theorises that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow incremen ...

to explain the patterns of extinction and faunal succession revealed by the fossil record.

Knowledge of the fossil record continued to advance rapidly during the first few decades of the 19th century. By the 1840s, the outlines of the geologic timescale

The geologic time scale, or geological time scale, (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochr ...

were becoming clear, and in 1841 John Phillips named three major eras, based on the predominant fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is '' flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. ...

of each: the Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ...

, dominated by marine invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chorda ...

s and fish, the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

, the age of reptiles, and the current Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configu ...

age of mammals. This progressive picture of the history of life was accepted even by conservative English geologists like Adam Sedgwick

Adam Sedgwick (; 22 March 1785 – 27 January 1873) was a British geologist and Anglican priest, one of the founders of modern geology. He proposed the Cambrian and Devonian period of the geological timescale. Based on work which he did on ...

and William Buckland

William Buckland DD, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full account of a fossil dinosaur, which he named ' ...

; however, like Cuvier, they attributed the progression to repeated catastrophic episodes of extinction followed by new episodes of creation. Unlike Cuvier, Buckland and some other advocates of natural theology among British geologists made efforts to explicitly link the last catastrophic episode proposed by Cuvier to the biblical flood

The Genesis flood narrative (chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis) is the Hebrew version of the universal flood myth. It tells of God's decision to return the universe to its pre- creation state of watery chaos and remake it through the microc ...

.[

]

From 1830 to 1833, geologist Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

published his multi-volume work ''Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830–1833. Ly ...

'', which, building on Hutton's ideas, advocated a uniformitarian alternative to the catastrophic theory of geology. Lyell claimed that, rather than being the products of cataclysmic (and possibly supernatural) events, the geologic features of the Earth are better explained as the result of the same gradual geologic forces observable in the present day—but acting over immensely long periods of time. Although Lyell opposed evolutionary ideas (even questioning the consensus that the fossil record demonstrates a true progression), his concept that the Earth was shaped by forces working gradually over an extended period, and the immense age of the Earth assumed by his theories, would strongly influence future evolutionary thinkers such as Charles Darwin.

Transmutation of species

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck proposed, in his ''

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck proposed, in his ''Philosophie zoologique

''Philosophie zoologique'' ("Zoological Philosophy, or Exposition with Regard to the Natural History of Animals") is an 1809 book by the French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, in which he outlines his pre-Darwinian theory of evolution, part of ...

'' of 1809, a theory of the transmutation of species (''transformisme''). Lamarck did not believe that all living things shared a common ancestor but rather that simple forms of life were created continuously by spontaneous generation. He also believed that an innate life force

Life force or lifeforce may refer to:

* Spirit (vital essence), in folk belief, the vital principle or animating force within all living things

* Vitality, ability to live or exist

* Vitalism, the belief in the existence of vital energy

** Energ ...

drove species to become more complex over time, advancing up a linear ladder of complexity that was related to the great chain of being. Lamarck recognized that species adapted to their environment. He explained this by saying that the same innate force driving increasing complexity caused the organs of an animal (or a plant) to change based on the use or disuse of those organs, just as exercise affects muscles. He argued that these changes would be inherited by the next generation and produce slow adaptation to the environment. It was this secondary mechanism of adaptation through the inheritance of acquired characteristics that would become known as Lamarckism

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

and would influence discussions of evolution into the 20th century.

A radical British school of comparative anatomy that included the anatomist

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having it ...

Robert Edmond Grant was closely in touch with Lamarck's French school of ''Transformationism''. One of the French scientists who influenced Grant was the anatomist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire

Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (15 April 177219 June 1844) was a French naturalist who established the principle of "unity of composition". He was a colleague of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and expanded and defended Lamarck's evolutionary theories ...

, whose ideas on the unity of various animal body plans and the homology of certain anatomical structures would be widely influential and lead to intense debate with his colleague Georges Cuvier. Grant became an authority on the anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having i ...

and reproduction of marine invertebrates. He developed Lamarck's and Erasmus Darwin's ideas of transmutation and evolutionism

Evolutionism is a term used (often derogatorily) to denote the theory of evolution. Its exact meaning has changed over time as the study of evolution has progressed. In the 19th century, it was used to describe the belief that organisms deliberat ...

, and investigated homology, even proposing that plants and animals had a common evolutionary starting point. As a young student, Charles Darwin joined Grant in investigations of the life cycle of marine animals. In 1826, an anonymous paper, probably written by Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson FRS FRSE (11 July 1774 – 19 April 1854) was a Scottish naturalist and mineralogist.

As Regius Professor of Natural History at the University of Edinburgh for fifty years, developing his predecessor John ...

, praised Lamarck for explaining how higher animals had "evolved" from the simplest worms; this was the first use of the word "evolved" in a modern sense. In 1844, the Scottish publisher Robert Chambers anonymously published an extremely controversial but widely read book entitled ''

In 1844, the Scottish publisher Robert Chambers anonymously published an extremely controversial but widely read book entitled ''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation

''Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation'' is an 1844 work of speculative natural history and philosophy by Robert Chambers. Published anonymously in England, it brought together various ideas of stellar evolution with the progressive tra ...

''. This book proposed an evolutionary scenario for the origins of the Solar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

and of life on Earth. It claimed that the fossil record showed a progressive ascent of animals, with current animals branching off a main line that leads progressively to humanity. It implied that the transmutations lead to the unfolding of a preordained plan that had been woven into the laws that governed the universe. In this sense it was less completely materialistic than the ideas of radicals like Grant, but its implication that humans were only the last step in the ascent of animal life incensed many conservative thinkers. The high profile of the public debate over ''Vestiges'', with its depiction of evolution as a progressive process, would greatly influence the perception of Darwin's theory a decade later.

Ideas about the transmutation of species were associated with the radical materialism

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materialis ...

of the Enlightenment and were attacked by more conservative thinkers. Cuvier attacked the ideas of Lamarck and Geoffroy, agreeing with Aristotle that species were immutable. Cuvier believed that the individual parts of an animal were too closely correlated with one another to allow for one part of the anatomy to change in isolation from the others, and argued that the fossil record showed patterns of catastrophic extinctions followed by repopulation, rather than gradual change over time. He also noted that drawings of animals and animal mummies from Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

, which were thousands of years old, showed no signs of change when compared with modern animals. The strength of Cuvier's arguments and his scientific reputation helped keep transmutational ideas out of the mainstream for decades.

In

In Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

, the philosophy of natural theology remained influential. William Paley

William Paley (July 174325 May 1805) was an English clergyman, Christian apologist, philosopher, and utilitarian. He is best known for his natural theology exposition of the teleological argument for the existence of God in his work ''Natu ...

's 1802 book ''Natural Theology

Natural theology, once also termed physico-theology, is a type of theology that seeks to provide arguments for theological topics (such as the existence of a deity) based on reason and the discoveries of science.

This distinguishes it from ...

'' with its famous watchmaker analogy had been written at least in part as a response to the transmutational ideas of Erasmus Darwin. Geologists influenced by natural theology, such as Buckland and Sedgwick, made a regular practice of attacking the evolutionary ideas of Lamarck, Grant, and ''Vestiges''. Although Charles Lyell opposed scriptural geology, he also believed in the immutability of species, and in his ''Principles of Geology'', he criticized Lamarck's theories of development.Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he rec ...

and Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Ow ...

believed that each species was fixed and unchangeable because it represented an idea in the mind of the creator. They believed that relationships between species could be discerned from developmental patterns in embryology, as well as in the fossil record, but that these relationships represented an underlying pattern of divine thought, with progressive creation leading to increasing complexity and culminating in humanity. Owen developed the idea of "archetypes" in the Divine mind that would produce a sequence of species related by anatomical homologies, such as vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, with ...