Prison Farm on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A prison farm (also known as a penal farm) is a large

A prison farm (also known as a penal farm) is a large  Louisiana State Penitentiary is the largest prison farm covering , and is bordered on three sides by the Mississippi River. Canada has six large prison farms that are currently closed with the possibility of being reopened.

Louisiana State Penitentiary is the largest prison farm covering , and is bordered on three sides by the Mississippi River. Canada has six large prison farms that are currently closed with the possibility of being reopened.

This type of penal institution has mainly been implanted in rural regions of vast countries. For example, the following passage describes the prison system of the U.S. state of North Carolina in the early twentieth century:

This type of penal institution has mainly been implanted in rural regions of vast countries. For example, the following passage describes the prison system of the U.S. state of North Carolina in the early twentieth century:

Prison farms facing execution

" ''

A prison farm (also known as a penal farm) is a large

A prison farm (also known as a penal farm) is a large correctional facility

In criminal justice, particularly in North America, correction, corrections, and correctional, are umbrella terms describing a variety of functions typically carried out by government agencies, and involving the punishment, treatment, and s ...

where penal labor convicts are forced to work on a farm

A farm (also called an agricultural holding) is an area of land that is devoted primarily to agricultural processes with the primary objective of producing food and other crops; it is the basic facility in food production. The name is used fo ...

legally and illegally (in the wide sense of a productive unit), usually for manual labor, largely in the open air, such as in agriculture, logging, quarrying, and mining as well as many others. All of this forced labor has been given the right from the thirteenth amendment in the United States, however other parts of the world have made penal labor illegal. The concepts of prison farm and labor camp

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (especi ...

overlap with the idea that they are forced to work. The historical equivalent on a very large scale was called a penal colony

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer to ...

.

The agricultural goods produced by prison farms are generally used primarily to feed the prisoners themselves and other wards of the state (residents of orphanages, asylums, etc.), and secondarily, to be sold for whatever profit the state may be able to obtain.

In addition to being forced to labor directly for the government on a prison farm or in a penal colony, inmates may be forced to do farm work for private enterprises by being farmed out through the practice of convict leasing

Convict leasing was a system of forced penal labor which was practiced historically in the Southern United States, the laborers being mainly African-American men; it was ended during the 20th century. (Convict labor in general continues; f ...

to work on private agricultural lands or related industries (fishing, lumbering, etc.). The party purchasing their labor from the government generally does so at a steep discount from the cost of free labor.

Louisiana State Penitentiary is the largest prison farm covering , and is bordered on three sides by the Mississippi River. Canada has six large prison farms that are currently closed with the possibility of being reopened.

Louisiana State Penitentiary is the largest prison farm covering , and is bordered on three sides by the Mississippi River. Canada has six large prison farms that are currently closed with the possibility of being reopened.

Convict leasing

''For more information, seeConvict Leasing

Convict leasing was a system of forced penal labor which was practiced historically in the Southern United States, the laborers being mainly African-American men; it was ended during the 20th century. (Convict labor in general continues; f ...

''

Convict leasing was a system of penal labor that was primarily practiced in the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

, and widely involved the use of African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

men which was prominently used after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. In this system southern states leased prisoners to large plantations and private mines or railways. This system led to the states earning a profit, while the prisoners earned no pay and faced dangerous working conditions.

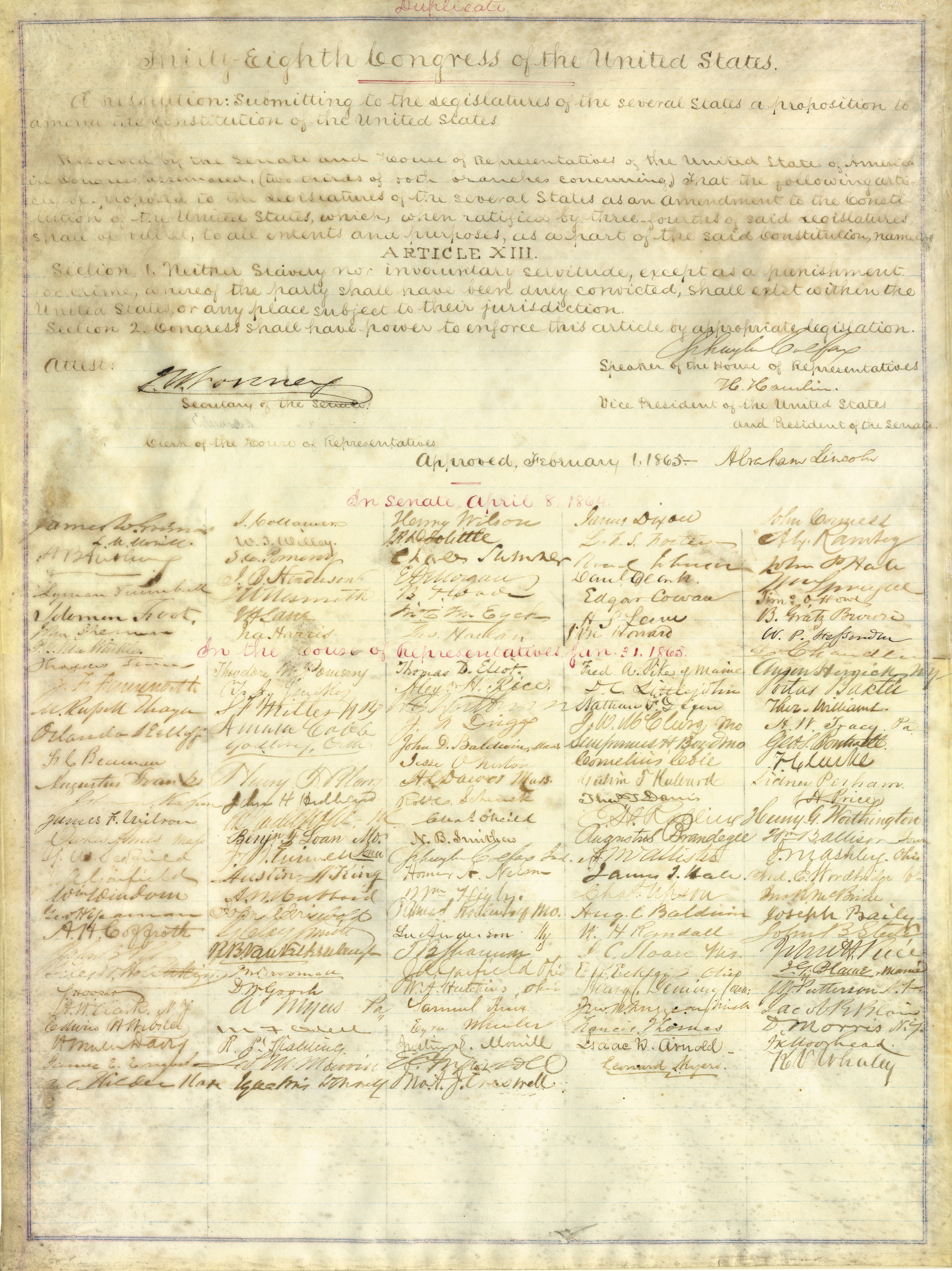

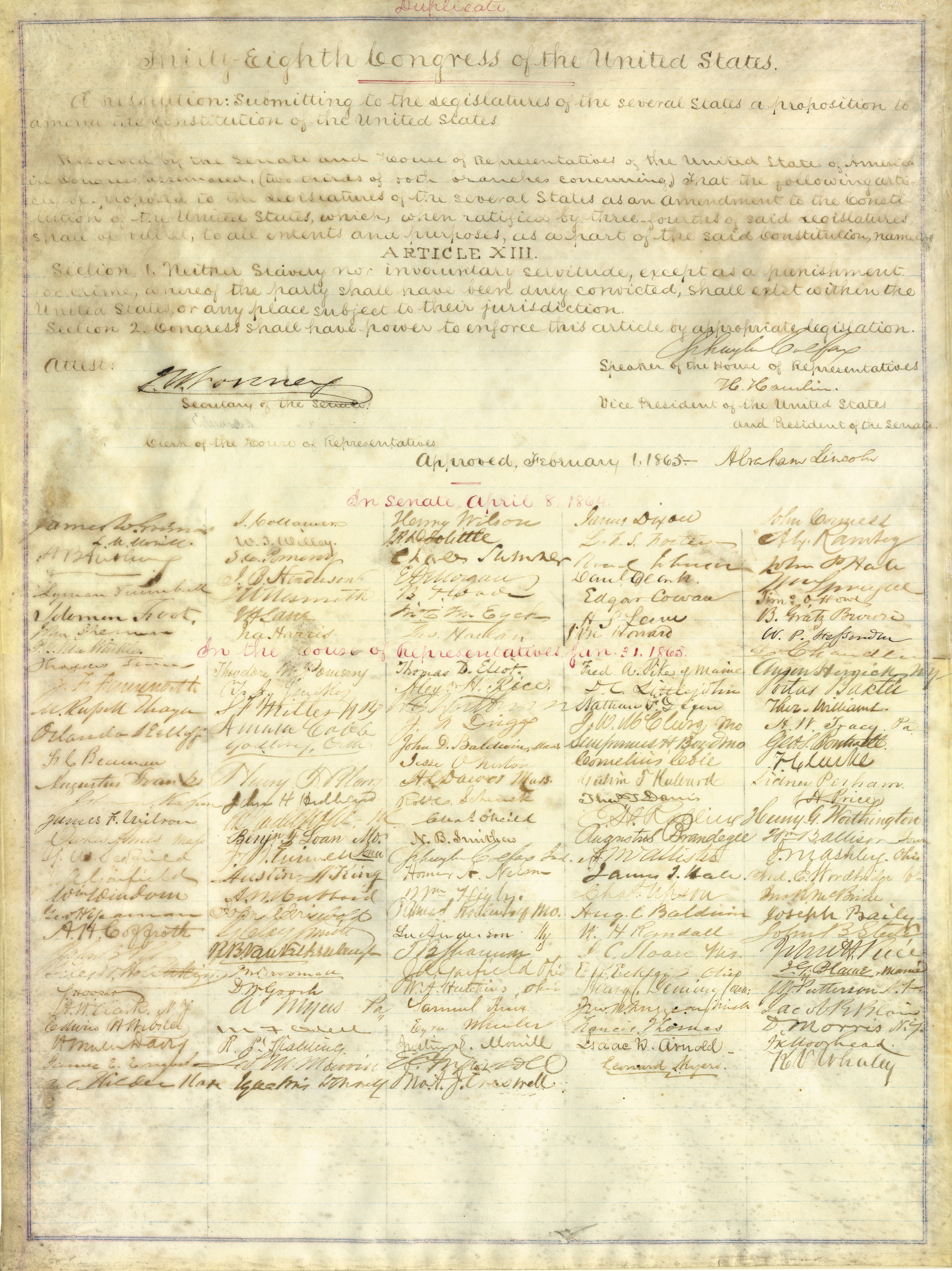

The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

, prohibited the use of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and involuntary servitude but explicitly exempts those who have been convicted of a crime. In response to this, the southern state legislatures implemented " Black Codes" which were laws that explicitly applied to African-Americans and subjected them to criminal prosecution for more minor offenses like breaking curfew, loitering, and not carrying proof of employment. These new laws led to more prisoners for the penal system that could all be leased by the state so that they can use their labor for profit. Widespread convict leasing ended by World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, but the loopholes in the 13th Amendment still permit the use of prisoners to work without pay.

Other work programs

Convicts may also be leased for non-agricultural work, either directly to state entities, or to private industry. For example, prisoners may make license plates under contract to the state Department of Motor Vehicles, work in textile or other state-run factories, or may perform data processing for outside firms. Other types of work include food service or groundskeeping. These laborers are typically considered to be a part of prison industries and not prison farms.In the United States (partial list)

Canadian Prison Farm System

In 2009,Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

shut down six of their major prison farms. Canada had used their prison farms as a way to generate revenue, as well as to give prisoners skills post-release. In 2009, the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

in Canada announced that the skills that prison farms had been giving inmates were outdated, and that prison labor should focus on work related to more modern skills.

Although the Canadian prison farm system has been shut down since 2009,the debate of whether or not the farms should reopen has continued. The group called Save our Prison Farms (SOPF) has been trying to revive the prison farm concept, since they did not want to pay for farm labor. When active, the prison farms highlighted many inherent inequalities within Canadian society. For example, the incarceration rate of the indigenous "First Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

**First Natio ...

" people of Canada was ten times greater than that of non-aboriginal Canadians.

When the Prison farm Program in Canada was about to shut down in 2009, the Government of Canada

The government of Canada (french: gouvernement du Canada) is the body responsible for the federal administration of Canada. A constitutional monarchy, the Crown is the corporation sole, assuming distinct roles: the executive, as the ''Crown ...

gave three reasons to cut the program:

*The first reason cited was how dangerous the conditions were for the people that worked on the farm.

*The second reason was that they thought the program was an out of date and ineffective type of correction giving non-modern skills to inmates for their post release.

*The third reason was because it was losing money.

The six prisons revenue was CA$7.5 million, while the expenses were CA$11.5 million, with a net loss to the government of about four million dollars on a useless program. Since the Canadian Prison Farm Program was found to not be effective, along with its inherent inequalities, it seemed to make sense to just shut it down altogether.

Legal framework

The 13th Amendment to theUnited States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

, which ended slavery, specifically carved out the concept of penal servitude (i.e., forced and unpaid labor as a punishment for a crime). This exemption only affected those who have been convicted of crimes, not those who were still awaiting trial.

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

had a long history of penal servitude even before passage of the Penal Servitude Act of 1853, and routinely used convict labor to settle its conquests, either through penal colonies or by selling convicts to settlers to serve as slaves for a term of years as indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

.

Scope

This type of penal institution has mainly been implanted in rural regions of vast countries. For example, the following passage describes the prison system of the U.S. state of North Carolina in the early twentieth century:

This type of penal institution has mainly been implanted in rural regions of vast countries. For example, the following passage describes the prison system of the U.S. state of North Carolina in the early twentieth century:

"The state prison is at Raleigh, although most of the convicts are distributed upon farms owned and operated by the state. The lease system does not prevail, but the farming out of convict labor is permitted by the constitution; such labor is used chiefly for the building of railways, the convicts so employed being at all times cared for and guarded by state officials. A reformatory for white youth between the ages of seven and sixteen, under the name of theIn 21st-century Illinois, several prisons continue to run farms to produce food for wards of the state, including the prisoners themselves. The 1911 Britannica also reported that the state of Rhode Island had a farm of in the southern part of Cranston City housing (and presumably taking labor from):Stonewall Jackson Manual Training and Industrial School The Stonewall Jackson Youth Development Center is a juvenile correctional facility of the North Carolina Department of Public Safety located in unincorporated area, unincorporated Cabarrus County, North Carolina, near Concord, North Carolina, Co ..., was opened at Concord in 1909, and in March 1909 the Foulk Reformatory and Manual Training School for negro youth was provided for. Charitable and penal institutions are under the supervision of a Board of Public Charities, appointed by the governor for a period of six years, the terms of the different members expiring in different years. Private institutions for the care of the insane, idiots, feeble-minded, and inebriates may be established, but must be licensed and regulated by the state board and become legally a part of the system of public charities."

"the state prison, the Providence county jail, the state workhouse and the house of correction, the state almshouse, the state hospital for the insane, the Sockanosset school for boys, and the Oaklawn school for girls, the last two being departments of the state reform school."There are prison farms in other countries. Canada had six prison farms, where up to 800 inmates did everything from tending pigs to milking cows until they were closed in 2010 by the Conservative government. In 2015, the Liberal government began conducting feasibility studies to determine if the program can be restarted. In 2018, the Liberal government announced plans to reopen 2 of the prison farms previously closed by the end of 2019.

In fiction

Films and television shows featuring prison farms and forced prison labor: * ''I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang

''I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang'' is a 1932 American pre-Code crime-drama film directed by Mervyn LeRoy and starring Paul Muni as a wrongfully convicted man on a chain gang who escapes to Chicago. It was released on November 10, 1932. The f ...

'' is a movie released in 1932, which depicted the degrading and inhumane treatment on chain gang

A chain gang or road gang is a group of prisoners chained together to perform menial or physically challenging work as a form of punishment. Such punishment might include repairing buildings, building roads, or clearing land. The system was no ...

s in the post–World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

era.

* '' Hell's Highway'' (1932)

* ''Prison Farm

A prison farm (also known as a penal farm) is a large correctional facility where penal labor convicts are forced to work on a farm legally and illegally (in the wide sense of a productive unit), usually for manual labor, largely in the open ai ...

'' (1938)

* ''Gone with the Wind

Gone with the Wind most often refers to:

* ''Gone with the Wind'' (novel), a 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell

* ''Gone with the Wind'' (film), the 1939 adaptation of the novel

Gone with the Wind may also refer to:

Music

* ''Gone with the Wind'' ...

'' (1939) scenes of Scarlett O'Hara's leased convicts at work in her lumber mills

* ''Sullivan's Travels

''Sullivan's Travels'' is a 1941 American comedy film written and directed by Preston Sturges. A satire on the film industry, it follows a famous Hollywood comedy director (Joel McCrea) who, longing to make a socially relevant drama, sets out to ...

'' (1941)

* ''City Without Men

''City Without Men'' is a 1943 American film noir crime film directed by Sidney Salkow and starring Linda Darnell, Edgar Buchanan and Michael Duane. It was released by Columbia Pictures on January 14, 1943. A group of women lives in a boarding ...

'' (1943)

* ''Chain Gang'' (1950) starred Douglas Kennedy (actor)

Douglas Richards Kennedy (September 14, 1915 – August 10, 1973) was an American supporting actor originally from New York City who appeared in more than 190 films between 1935 and 1973.

Early years

Kennedy was the son of Mr. and Mrs. ...

as a reporter working as a guard to expose corruption and brutality.

* ''Cool Hand Luke

''Cool Hand Luke'' is a 1967 American prison drama film directed by Stuart Rosenberg, starring Paul Newman and featuring George Kennedy in an Oscar-winning performance. Newman stars in the title role as Luke, a prisoner in a Florida prison cam ...

'' (1967)

* '' Sounder'' (1972)

* '' Papillon'' (1973)

* ''Scarecrow

A scarecrow is a decoy or mannequin, often in the shape of a human. Humanoid scarecrows are usually dressed in old clothes and placed in open fields to discourage birds from disturbing and feeding on recently cast seed and growing crops.Lesley ...

'' (1973)

* ''Nightmare in Badham County

''Nightmare in Badham County'' is a 1976 American women-in-prison television film directed by John Llewellyn Moxey and starring Chuck Connors, Deborah Raffin, and Lynne Moody. Its plot follows two female college students from California who, w ...

'' (1976)

* '' Buckstone County Prison'' (1978)

* ''They Went That-A-Way & That-A-Way

''They Went That-A-Way & That-A-Way'' is a 1978 slapstick comedy film co-directed by Stuart E. McGowan and Edward Montagne and written by and starring Tim Conway.

Premise

Dewey and Wallace are small-town lawmen who are ordered by the governor t ...

'' (1978)

* ''Brubaker

''Brubaker'' is a 1980 American prison drama film directed by Stuart Rosenberg. It stars Robert Redford as a newly arrived prison warden, Henry Brubaker, who attempts to clean up a corrupt and violent penal system. The screenplay by W. D. Richte ...

'' (1980)

* ''MacGyver

Angus "Mac" MacGyver is the title character and the protagonist in the TV series ''MacGyver''. He is played by Richard Dean Anderson in the 1985 original series. Lucas Till portrays a younger version of MacGyver in the 2016 reboot.

In both p ...

'' (1988), "Jack of Spies", Season 3. Mac's friend Jack Dalton tricks him to be arrested by a corrupt police officer to be incarcerated in a prison farm that uses the inmates to work in an underground gold mine to find a stash of hidden money.

* ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energ ...

'' (1999)

* ''O Brother, Where Art Thou?

''O Brother, Where Art Thou?'' is a 2000 comedy drama film written, produced, co-edited, and directed by Joel and Ethan Coen. It stars George Clooney, John Turturro, and Tim Blake Nelson, with Chris Thomas King, John Goodman, Holly Hunter, and ...

'' (2000)

* ''Civil Brand

''Civil Brand'' is a 2002 feature film written by Preston A. Whitmore II and Joyce Renee Lewis, and directed by Neema Barnette. It features Da Brat, N'Bushe Wright, Mos Def, LisaRaye McCoy, and Monica Calhoun. The film is about a group of femal ...

'' (2002)

* In "Les Misérables

''Les Misérables'' ( , ) is a French historical novel by Victor Hugo, first published in 1862, that is considered one of the greatest novels of the 19th century.

In the English-speaking world, the novel is usually referred to by its original ...

" by Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

, which has had several movie adaptations, the character Jean Valjean

Jean Valjean () is the protagonist of Victor Hugo's 1862 novel ''Les Misérables''. The story depicts the character's struggle to lead a normal life and redeem himself after serving a 19-year-long prison sentence for stealing bread to feed his ...

is part of a chain gang ("le bagne", which is usually translated as "the galleys" or "the prison hulks") as part of his punishment for stealing bread.

See also

* Care farming *Chain gang

A chain gang or road gang is a group of prisoners chained together to perform menial or physically challenging work as a form of punishment. Such punishment might include repairing buildings, building roads, or clearing land. The system was no ...

* Gorgona Agricultural Penal Colony

The Gorgona Agricultural Penal Colony is an Italian prison farm located on the island of Gorgona, Italy, Gorgona in the Tuscan Archipelago. The island has a long history of being home to monastic communities, with the Gorgona Abbey being a promi ...

* Iwahig Prison and Penal Farm

Iwahig Prison and Penal Farm in Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines is one of seven operating units of the Bureau of Corrections under the Department of Justice.

History

American territorial period

The Spanish regime had earlier ...

* Old Atlanta Prison Farm

* Tom Murton

* Trusty system

References

*Further reading

* Thomas, Nicki (Producer: Scott Croteau)Prison farms facing execution

" ''

Capital News Online

Carleton University is an English-language public university, public research university in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Founded in 1942 as Carleton College, the institution originally operated as a private, non-denominational evening college to ser ...

''. Carleton University

Carleton University is an English-language public research university in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Founded in 1942 as Carleton College, the institution originally operated as a private, non-denominational evening college to serve returning World ...

School of Journalism and Communication. March 5, 2010.

* David M. Oshinsky, "Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

Justice," On the origins of the penal farm in Mississippi and the preceding convict lease

Convict leasing was a system of forced penal labor which was practiced historically in the Southern United States, the laborers being mainly African-American men; it was ended during the 20th century. (Convict labor in general continues; f ...

system.

* Sample, Albert. ''Racehoss: Big Emma's Boy.'' Austin: Eakin Press, 1984.

External links

{{Incarceration Types of farms Prisons Imprisonment and detention Penal labour