Presidency of Benjamin Harrison on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The initial favorite for the Republican nomination in the 1888 presidential election was

The initial favorite for the Republican nomination in the 1888 presidential election was  Harrison's opponent in the general election was incumbent President

Harrison's opponent in the general election was incumbent President

Harrison was sworn into office on March 4, 1889 by Chief Justice

Harrison was sworn into office on March 4, 1889 by Chief Justice

Harrison's cabinet choices alienated pivotal Republican operatives from New York to Pennsylvania to Iowa and prematurely compromised his political power and future. Senator Shelby Cullom's described Harrison's steadfast aversion to the use of federal positions for patronage, stating, "I suppose Harrison treated me as well as he did any other Senator; but whenever he did anything for me, it was done so ungraciously that the concession tended to anger rather than please." Harrison began the process of forming a cabinet by choosing to delay the nomination of James G. Blaine as Secretary of State. Harrison felt that Blaine had, as President

Harrison's cabinet choices alienated pivotal Republican operatives from New York to Pennsylvania to Iowa and prematurely compromised his political power and future. Senator Shelby Cullom's described Harrison's steadfast aversion to the use of federal positions for patronage, stating, "I suppose Harrison treated me as well as he did any other Senator; but whenever he did anything for me, it was done so ungraciously that the concession tended to anger rather than please." Harrison began the process of forming a cabinet by choosing to delay the nomination of James G. Blaine as Secretary of State. Harrison felt that Blaine had, as President

online

/ref>A.T. Volwiler, "Harrison, Blaine, and American Foreign Policy, 1889-1893" ''Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society'' 79#4 1938) pp. 637-64

online

/ref>Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 111. Blaine served in the cabinet until 1892, when he resigned due to poor health. He was replaced by John W. Foster, an experienced diplomat. For the important position of Secretary of the Treasury, Harrison rejected Thomas C. Platt and Warner Miller, two powerful New York Republicans who fought for control of their state party. He instead selected

Harrison appointed four justices to the

Harrison appointed four justices to the

Members of both parties were concerned with the growth and power of

Members of both parties were concerned with the growth and power of

In violation of the Fifteenth Amendment, many Southern states denied African-Americans the right to vote. Convinced that the "lily-white policy" of attempting to attract white Southerners to the Republican Party had failed, and believing that the disenfranchisement of African-American voters was immoral, Harrison endorsed the Federal Elections Bill. The bill, written by Representative

In violation of the Fifteenth Amendment, many Southern states denied African-Americans the right to vote. Convinced that the "lily-white policy" of attempting to attract white Southerners to the Republican Party had failed, and believing that the disenfranchisement of African-American voters was immoral, Harrison endorsed the Federal Elections Bill. The bill, written by Representative

During Harrison's time in office, the United States was continuing to experience advances in science and technology, and Harrison was the earliest president whose voice is known to be preserved. That was originally made on a wax

During Harrison's time in office, the United States was continuing to experience advances in science and technology, and Harrison was the earliest president whose voice is known to be preserved. That was originally made on a wax

In 1891, a new diplomatic crisis, known as the ''Baltimore'' Crisis, emerged in

In 1891, a new diplomatic crisis, known as the ''Baltimore'' Crisis, emerged in

Harrison's wife Caroline began a critical struggle with

Harrison's wife Caroline began a critical struggle with

online

* Spetter, Allan. "Harrison and Blaine: Foreign Policy, 1889-1893" ''Indiana Magazine of History'' 65#3 (1969), pp. 214–22

online

* * Volwiler, A. T. "Harrison, Blaine, and American Foreign Policy, 1889-1893" ''Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society'' 79#4 1938) pp. 637–64

online

h1>

online

*Calhoun, Charles W. "Benjamin Harrison, Centennial President: A Review Essay." ''Indiana Magazine of History'' (1988)

online

* Dozer, Donald Marquand. "Benjamin Harrison and the Presidential Campaign of 1892." ''American Historical Review'' 54.1 (1948): 49-77

online

* Gunderson, Megan M. ''Benjamin Harrison'' (2009

for middle schools

* Holbrook, Francis X., and John Nikol. "Chilean Crisis of 1891-1892." ''American Neptune'' 38.4 (1978): 291-300. * Rhodes, James Ford. ''History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850: 1877–1896'' (1919

online complete

old, factual and heavily political, by winner of Pulitzer Prize * Ringenberg, William C. "Benjamin Harrison: The Religious Thought and Practice of a Presbyterian President." ''American Presbyterians'' 64.3 (1986): 175-189

online

* Sievers, Harry Joseph. ''Benjamin Harrison, Hoosier president: The White House and after'' (1968), vol 3 of his thin but scholarly biography * Sinkler, George. "Benjamin Harrison and the Matter of Race." ''Indiana Magazine of History'' (1969): 197-213

online

* Socolofsky, Homer E. "Benjamin Harrison and the American west." ''Great Plains Quarterly'' (1985): 249-258

online

* Taylor, Mark Zachary. "Ideas and Their Consequences: Benjamin Harrison and the Seeds of Economic Crisis, 1889-1893." ''Critical Review'' 33.1 (2021): 102-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08913811.2020.1881354 * Wilson, Kirtley Hasketh. "The problem with public memory: Benjamin Harrison confronts the 'southern question'." in ''Before the rhetorical presidency'' (Texas A&M University Press, 2008) pp. 267-288.

online

* Harrison, Benjamin. ''Speeches of Benjamin Harrison, Twenty-third President of the United States'' (DigiCat, 2022

online

* Volwiler, Albert T., ed. ''The Correspondence between Benjamin Harrison and James G. Blaine, 1882–1893'' (1940) {{Authority control 1880s in the United States 1890s in the United States 1889 establishments in the United States 1893 disestablishments in the United States Harrison, Benjamin

Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pre ...

's term as the president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United St ...

lasted from March 4, 1889, until March 4, 1893. Harrison, a Republican, took office as the 23rd United States president after defeating Democratic incumbent President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

in the 1888 election. Four years later he was defeated for re-election by Cleveland in the 1892 presidential election

The following elections occurred in the year 1892.

{{TOC right

Asia Japan

* 1892 Japanese general election

Europe Denmark

* 1892 Danish Folketing election

Portugal

* 1892 Portuguese legislative election

United Kingdom

* 1892 Chelmsford by-e ...

.

Harrison and the Republican-controlled 51st United States Congress

The 51st United States Congress, referred to by some critics as the Billion Dollar Congress, was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Rep ...

(derided by Democrats as the "Billion Dollar Congress") enacted the most ambitious domestic agenda of the late-nineteenth century. Hallmarks of his administration include the McKinley Tariff

The Tariff Act of 1890, commonly called the McKinley Tariff, was an act of the United States Congress, framed by then Representative William McKinley, that became law on October 1, 1890. The tariff raised the average duty on imports to almost fift ...

, which imposed historic protective trade rates, and the Sherman Antitrust Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (, ) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce. It was passed by Congress and is named for Senator John Sherman, its principal author.

T ...

, which empowered the federal government to investigate and prosecute trust

Trust often refers to:

* Trust (social science), confidence in or dependence on a person or quality

It may also refer to:

Business and law

* Trust law, a body of law under which one person holds property for the benefit of another

* Trust (bus ...

s. Due in large part to surplus revenues from the tariffs, federal spending reached one billion dollars for the first time during his term. Harrison facilitated the creation of the National Forests through an amendment to the General Revision Act

The General Revision Act (sometimes Land Revision Act) of 1891, also known as the Forest Reserve Act of 1891, was a federal law signed in 1891 by President Benjamin Harrison. The Act reversed previous policy initiatives, such as the Timber Culture ...

(1891), and substantially strengthened and modernized the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage of ...

. He proposed, in vain, federal education funding as well as voting rights

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

enforcement for African Americans in the South. Harrison's presidency saw the addition of six new states, more than any other president. In foreign affairs, Harrison vigorously promoted American exports, sought tariff reciprocity in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

, and worked to increase U.S. influence across the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

.

Although many historians have praised Harrison's personal integrity and commitment to minority voting rights, scholars and historians generally rank Harrison in the bottom half of U.S. presidents. Nonetheless, Harrison's ambitious domestic policy and assertive foreign policy set a precedent for the more powerful presidencies of the 20th century.

Election of 1888

The initial favorite for the Republican nomination in the 1888 presidential election was

The initial favorite for the Republican nomination in the 1888 presidential election was James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine (January 31, 1830January 27, 1893) was an American statesman and Republican politician who represented Maine in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876, serving as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representativ ...

, the party's nominee in the 1884 presidential election. After Blaine wrote several letters denying any interest in the nomination, his supporters divided among other candidates, with John Sherman

John Sherman (May 10, 1823October 22, 1900) was an American politician from Ohio throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century. A member of the Republican Party, he served in both houses of the U.S. Congress. He also served a ...

of Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

as the leader among them. Others, including Chauncey Depew

Chauncey Mitchell Depew (April 23, 1834April 5, 1928) was an American attorney, businessman, and Republican politician. He is best remembered for his two terms as United States Senator from New York and for his work for Cornelius Vanderbilt, as ...

of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* ...

, Russell Alger

Russell Alexander Alger (February 27, 1836 – January 24, 1907) was an American politician and businessman. He served as the 20th Governor of Michigan, U.S. Senator, and U.S. Secretary of War.

He was supposedly a distant relation of author ...

of Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

, and Walter Q. Gresham, a federal appellate judge, also sought the delegates' support at the 1888 Republican National Convention

The 1888 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held at the Auditorium Building in Chicago, Illinois, on June 19–25, 1888. It resulted in the nomination of former Senator Benjamin Harrison of Indiana for presid ...

. Blaine did not publicly endorse any of the candidates as a successor; however, on March 1, 1888 he privately wrote that "the one man remaining who in my judgment can make the best one is Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pre ...

."

Harrison represented Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th st ...

in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and power ...

from 1881 to 1887, but lost his 1886 bid for re-election. In February 1888, Harrison announced his candidacy for the Republican presidential nomination, declaring himself a "living and rejuvenated Republican." He placed fifth on the first ballot at the 1888 Republican convention, with Sherman in the lead; the next few ballots showed little change. The Blaine supporters shifted their support among different candidates, and when they shifted to Harrison, they found a candidate who could attract the votes of many other delegations. Harrison was nominated as the party's presidential candidate on the eighth ballot, by a count of 544 to 108 votes. Levi P. Morton of New York was chosen as his running mate.

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

. Harrison reprised the traditional front-porch campaign, which had been abandoned by Blaine in 1884. He received visiting delegations to Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

and made ninety plus pronouncements from his home town; Cleveland made only one public campaign appearance. The Republicans campaigned in favor of protective tariffs

Protective tariffs are tariffs that are enacted with the aim of protecting a domestic industry. They aim to make imported goods cost more than equivalent goods produced domestically, thereby causing sales of domestically produced goods to rise, ...

, turning out protectionist voters in the important industrial states of the North. The election focused on the swing state

In American politics, the term swing state (also known as battleground state or purple state) refers to any state that could reasonably be won by either the Democratic or Republican candidate in a statewide election, most often referring to pre ...

s of New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and Harrison's home state of Indiana. Harrison and Cleveland split these four states, with Harrison winning in New York and Indiana. Voter turnout was 79.3%, reflecting a large interest in the campaign; nearly eleven million votes were cast. Although he received approximately 90,000 fewer popular votes than Cleveland, Harrison won the electoral vote 233 to 168. This was the third U.S. presidential election in which the winner lost the popular vote.

Although Harrison had made no political bargains, his supporters had given many pledges upon his behalf. When Boss Matthew Quay

Matthew Stanley "Matt" Quay (September 30, 1833May 28, 1904) was an American politician of the Republican Party who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1887 until 1899 and from 1901 until his death in 1904. Quay's control ...

of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; (Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, Mary ...

heard that Harrison ascribed his narrow victory to Providence

Providence often refers to:

* Providentia, the divine personification of foresight in ancient Roman religion

* Divine providence, divinely ordained events and outcomes in Christianity

* Providence, Rhode Island, the capital of Rhode Island in the ...

, Quay exclaimed that Harrison would never know "how close a number of men were compelled to approach...the penitentiary to make him president." In the concurrent congressional elections, the Republicans increased their membership in the House of Representatives by nineteen seats, winning control of the chamber. The party also retained control of the Senate, giving one party unified control of Congress and the presidency for the first time since the 1874 elections. The Republican sweep allowed Harrison to pursue an ambitious legislative agenda in the resulting 51st Congress.

Inauguration

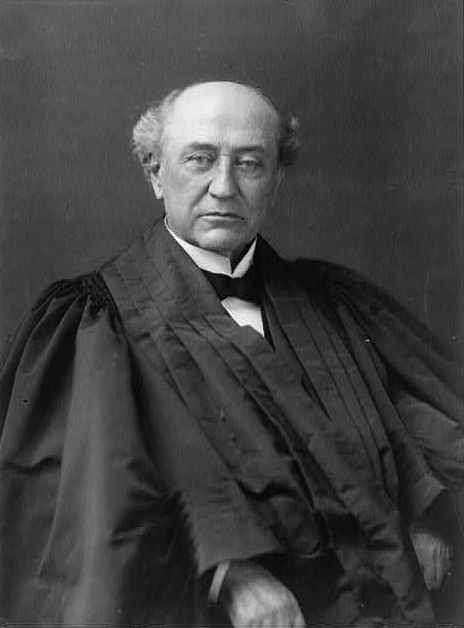

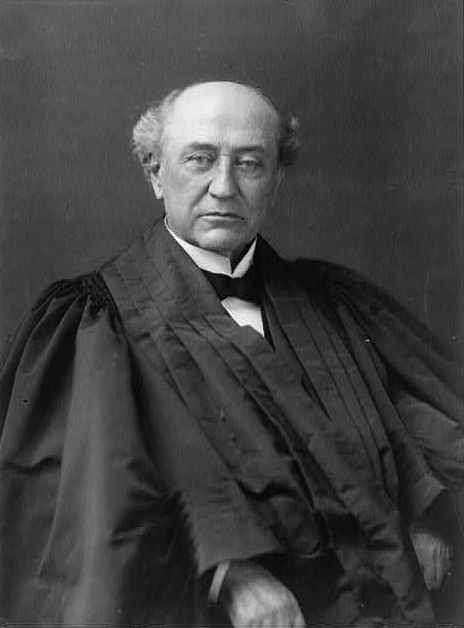

Harrison was sworn into office on March 4, 1889 by Chief Justice

Harrison was sworn into office on March 4, 1889 by Chief Justice Melville Fuller

Melville Weston Fuller (February 11, 1833 – July 4, 1910) was an American politician, attorney, and jurist who served as the eighth chief justice of the United States from 1888 until his death in 1910. Staunch conservatism marked his ...

. At 5' 6" tall, he was only slightly taller than James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

, the shortest president, but much heavier; he was also the fourth (and last) president to sport a full beard. Harrison's inauguration ceremony took place during a rainstorm in Washington D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, N ...

Outgoing President Grover Cleveland attended the ceremony and held an umbrella over Harrison's head as he took the oath of office. Harrison's speech was brief – half as long as that of his grandfather, William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

, whose speech holds the record for the longest inaugural address of a U.S. president.

In his speech, Benjamin Harrison credited the nation's growth to the influences of education and religion, urged the cotton states and mining territories to attain the industrial proportions of the eastern states, and promised a protective tariff. Concerning commerce, he said, "If our great corporations would more scrupulously observe their legal obligations and duties, they would have less call to complain of the limitations of their rights or of interference with their operations." He called for the regulation of trusts

A trust is a legal relationship in which the holder of a right gives it to another person or entity who must keep and use it solely for another's benefit. In the Anglo-American common law, the party who entrusts the right is known as the " sett ...

, safety laws for railroad employees, aid to education, and funding for internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, can ...

. Harrison also urged early statehood for the territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or an ...

and advocated pensions for veterans, a statement that was met with enthusiastic applause. In foreign affairs, Harrison reaffirmed the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

as a mainstay of foreign policy, while urging modernization of the Navy. He also gave his commitment to international peace through noninterference in the affairs of foreign governments.

Administration

Harrison's cabinet choices alienated pivotal Republican operatives from New York to Pennsylvania to Iowa and prematurely compromised his political power and future. Senator Shelby Cullom's described Harrison's steadfast aversion to the use of federal positions for patronage, stating, "I suppose Harrison treated me as well as he did any other Senator; but whenever he did anything for me, it was done so ungraciously that the concession tended to anger rather than please." Harrison began the process of forming a cabinet by choosing to delay the nomination of James G. Blaine as Secretary of State. Harrison felt that Blaine had, as President

Harrison's cabinet choices alienated pivotal Republican operatives from New York to Pennsylvania to Iowa and prematurely compromised his political power and future. Senator Shelby Cullom's described Harrison's steadfast aversion to the use of federal positions for patronage, stating, "I suppose Harrison treated me as well as he did any other Senator; but whenever he did anything for me, it was done so ungraciously that the concession tended to anger rather than please." Harrison began the process of forming a cabinet by choosing to delay the nomination of James G. Blaine as Secretary of State. Harrison felt that Blaine had, as President James Garfield

James Abram Garfield (November 19, 1831 – September 19, 1881) was the 20th president of the United States, serving from March 4, 1881 until his death six months latertwo months after he was shot by an assassin. A lawyer and Civil War gene ...

's Secretary of State-designate, held too much power in choosing the personnel of the Garfield administration, and he sought to avoid a similar scenario. Despite this early snub, Blaine and Harrison found common ground on most major policy issues. Blaine played a major role in Harrison's administration, though Harrison made most of the major policy decisions in foreign affairs.Allan Spetter, "Harrison and Blaine: Foreign Policy, 1889 1893." ''Indiana Magazine of History'' (1969) 65#3:214-27online

/ref>A.T. Volwiler, "Harrison, Blaine, and American Foreign Policy, 1889-1893" ''Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society'' 79#4 1938) pp. 637-64

online

/ref>Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 111. Blaine served in the cabinet until 1892, when he resigned due to poor health. He was replaced by John W. Foster, an experienced diplomat. For the important position of Secretary of the Treasury, Harrison rejected Thomas C. Platt and Warner Miller, two powerful New York Republicans who fought for control of their state party. He instead selected

William Windom

William Windom (May 10, 1827January 29, 1891) was an American politician from Minnesota. He served as U.S. Representative from 1859 to 1869, and as U.S. Senator from 1870 to January 1871, from March 1871 to March 1881, and from November 188 ...

, a native Midwesterner who lived in New York and who had served in the same position under Garfield. New York Republicans were also represented in the cabinet by Benjamin F. Tracy

Benjamin Franklin Tracy (April 26, 1830August 6, 1915) was a United States political figure who served as Secretary of the Navy from 1889 through 1893, during the administration of U.S. President Benjamin Harrison.

Biography

He was born in th ...

, who was appointed Secretary of the Navy. Former Governor Charles Foster of Ohio succeeded Windom upon the latter's death in 1891. Postmaster General John Wanamaker

John Wanamaker (July 11, 1838December 12, 1922) was an American merchant and religious, civic and political figure, considered by some to be a proponent of advertising and a "pioneer in marketing". He was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, a ...

represented Pennsylvania Republicans, many of whom were disappointed that their state party did not receive a more prominent cabinet seat. For the position of Secretary of the Agriculture, which had been established in the waning days of Cleveland's term, Harrison appointed Wisconsin Governor Jeremiah M. Rusk. John Noble

John Noble (born 20 August 1948) is an Australian actor. He is known for his roles as Denethor in the ''Lord of the Rings'' film trilogy, Dr. Walter Bishop on the science fiction series ''Fringe'', Henry Parrish on the action-horror series ' ...

, a railroad attorney with a reputation for incorruptibility, became the head of the scandal-plagued Department of the Interior. Redfield Proctor

Redfield Proctor (June 1, 1831March 4, 1908) was a U.S. politician of the Republican Party. He served as the 37th governor of Vermont from 1878 to 1880, as Secretary of War from 1889 to 1891, and as a United States Senator for Vermont from 18 ...

, a native of Vermont who had played a key role in Harrison's nomination, was rewarded with the position of Secretary of War. Proctor resigned in 1891 to take a Senate seat, at which point he was replaced by Stephen B. Elkins. Harrison's close friend and former law partner, William H. H. Miller, became Attorney General. Harrison's normal schedule provided for two full cabinet meetings per week, as well as separate weekly one-on-one meetings with each cabinet member.

Judicial appointments

Harrison appointed four justices to the

Harrison appointed four justices to the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. Federal tribunals in the United States, federal court cases, and over Stat ...

. The first was David Josiah Brewer

David Josiah Brewer (June 20, 1837 – March 28, 1910) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1890 to 1910. An appointee of President Benjamin Harrison, he supported states' righ ...

, a judge on the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. Brewer, the nephew of Associate Justice Field

Field may refer to:

Expanses of open ground

* Field (agriculture), an area of land used for agricultural purposes

* Airfield, an aerodrome that lacks the infrastructure of an airport

* Battlefield

* Lawn, an area of mowed grass

* Meadow, a grass ...

, had previously been considered for a cabinet position. Shortly after Brewer's nomination, Justice Matthews died, creating another vacancy. Harrison had considered Henry Billings Brown

Henry Billings Brown (March 2, 1836 – September 4, 1913) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1891 to 1906.

Although a respected lawyer and U.S. District Judge before ascending to the high court, Brown ...

, a Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

judge and admiralty law

Admiralty law or maritime law is a body of law that governs nautical issues and private maritime disputes. Admiralty law consists of both domestic law on maritime activities, and private international law governing the relationships between priva ...

expert, for the first vacancy and now nominated him for the second. For the third vacancy, which arose in 1892, Harrison nominated George Shiras. Shiras's appointment was somewhat controversial because his age—sixty—was older than usual for a newly appointed Justice, but he won Senate approval. Finally, at the end of his term, Harrison nominated Howell Edmunds Jackson

Howell Edmunds Jackson (April 8, 1832 – August 8, 1895) was an American attorney, politician, and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1893 until his death in 1895. His brief tenure on the Su ...

to replace Justice Lamar, who died in January 1893. Harrison knew the incoming Senate would be controlled by Democrats, so he selected Jackson, a respected Tennessee Democrat with whom he was friendly, to ensure his nominee would not be rejected. Jackson's nomination was indeed successful, but he died after only two years on the Court. The other Justices appointed by Harrison served past 1900, with Brewer the last to leave the Court, doing so upon his death in 1910.

Harrison signed the Judiciary Act of 1891

The Judiciary Act of 1891 ({{USStat, 26, 826), also known as the Evarts Act after its primary sponsor, Senator William M. Evarts, created the United States courts of appeals and reassigned the jurisdiction of most routine appeals from the district ...

, which abolished the United States circuit court

The United States circuit courts were the original intermediate level courts of the United States federal court system. They were established by the Judiciary Act of 1789. They had trial court jurisdiction over civil suits of diversity jurisdic ...

s and created the United States courts of appeal

The United States courts of appeals are the intermediate appellate courts of the United States federal judiciary. The courts of appeals are divided into 11 numbered circuits that cover geographic areas of the United States and hear appeals fro ...

. The act ended the practice of Supreme Court Justices "riding circuit

In the United States, circuit riding was the practice of a judge, sometimes referred to as a circuit rider, traveling to a judicial district (referred to as a circuit) to preside over court cases there. A defining feature of American federal cour ...

." The end of that custom combined with the creation of permanent intermediate appellate court

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much of ...

s significantly reduced the workload faced by the Supreme Court. Harrison appointed ten judges to the courts of appeal, two judges to the circuit courts, and 26 judges to the district courts. Because Harrison was in office when Congress eliminated the circuit courts in favor of the courts of appeals, he and Grover Cleveland were the only two presidents to have appointed judges to both bodies.

States admitted to the Union

More states were admitted during Harrison's presidency than any other. When Harrison took office, no new states had beenadmitted to the Union

''Admitted'' is a 2020 Indian Hindi-language docudrama film directed by Chandigarh-based director Ojaswwee Sharma. The film is about Dhananjay Chauhan, the first transgender student at Panjab University. The role of Dhananjay Chauhan has been pl ...

in more than a decade, owing to Congressional Democrats' reluctance to admit states that they believed would send Republican members. Seeking to bolster the party's majorities in the Senate, Republicans pushed bills admitting new states through the lame duck session of the 50th Congress. North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minnesota to the east, South ...

, South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large portion ...

, Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Colum ...

, and Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

all became states in November 1889. The following July, Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyomi ...

and Wyoming were also admitted. These states collectively sent twelve Republican senators to the 51st Congress.

Antitrust law

Members of both parties were concerned with the growth and power of

Members of both parties were concerned with the growth and power of trusts

A trust is a legal relationship in which the holder of a right gives it to another person or entity who must keep and use it solely for another's benefit. In the Anglo-American common law, the party who entrusts the right is known as the " sett ...

, which were business arrangements in which several competing companies combined to form one jointly-managed operation. Since the founding of Standard Oil

Standard Oil Company, Inc., was an American oil production, transportation, refining, and marketing company that operated from 1870 to 1911. At its height, Standard Oil was the largest petroleum company in the world, and its success made its co-f ...

in 1879, trusts created monopolies

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

in several areas of production, including steel, sugar, whiskey, and tobacco. The Harrison administration worked with congressional leaders to propose and pass the Sherman Antitrust Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (, ) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce. It was passed by Congress and is named for Senator John Sherman, its principal author.

T ...

, one of the first major acts of the 51st United States Congress

The 51st United States Congress, referred to by some critics as the Billion Dollar Congress, was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Rep ...

. The act specified that every "combination in the form of trust...in restraint of trade or commerce...is hereby declared to be illegal."

Along with the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887

The Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 is a United States federal law that was designed to regulate the railroad industry, particularly its monopolistic practices. The Act required that railroad rates be "reasonable and just," but did not empower ...

, the Sherman Act represented one of the first major federal steps taken by the federal government to regulate the economy. Harrison approved of the law and its intent, but his administration was not particularly vigorous in enforcing it. The Department of Justice was generally too understaffed to pursue complex antitrust

Competition law is the field of law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. Competition law is implemented through public and private enforcement. It is also known as antitrust ...

cases, and enforcement was further hampered by the vague language of the act and narrow interpretation of judges. Despite these hindrances, the government successfully concluded one case during Harrison's time in office (against a Tennessee coal company), and initiated several other cases against trusts. The relatively limited enforcement powers and the Supreme Court's narrow interpretation of the law would eventually inspire passage of the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914

The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 (, codified at , ), is a part of United States antitrust law with the goal of adding further substance to the U.S. antitrust law regime; the Clayton Act seeks to prevent anticompetitive practices in their incipie ...

.

Tariff

Tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and po ...

s accounted for 60 percent of federal revenue in 1889, and were a major source of political debate in the Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and West ...

. Along with a stable currency, high tariffs were the central aspect of Harrison's economic policy, since he believed that they protected domestic manufacturing jobs against cheap, imported goods. The high tariff rates had created a surplus of money in the Treasury, which led many Democrats, as well as the growing Populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develope ...

movement, to call for lowering them. Most Republicans, however, preferred to spend the budget surplus on internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, can ...

and eliminate some internal taxes. They saw their victory in the 1888 election as a mandate to raise tariff rates.

Harrison took an active role in the tariff debate, hosting dinner parties in which he would cajole members of Congress for their support of a new tariff bill. Representative William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

and Senator Nelson W. Aldrich

Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich (/ ˈɑldɹɪt͡ʃ/; November 6, 1841 – April 16, 1915) was a prominent American politician and a leader of the Republican Party in the United States Senate, where he represented Rhode Island from 1881 to 1911. By the ...

introduced the McKinley Tariff

The Tariff Act of 1890, commonly called the McKinley Tariff, was an act of the United States Congress, framed by then Representative William McKinley, that became law on October 1, 1890. The tariff raised the average duty on imports to almost fift ...

, which would raise the tariff and make some rates intentionally prohibitive so as to discourage imports. At Secretary of State James Blaine's urging, Harrison attempted to make the tariff by adding reciprocity provisions, which would allow the president to reduce rates when other countries reduced their own tariffs on American exports. The reciprocity features of the bill delegated an unusually high amount of power to the president for the time, as the president was granted the power to unilaterally modify tariff rates. The tariff was removed from imported raw sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double s ...

, and sugar growers in the United States were given a two cent per pound subsidy on their production. Congress passed the bill after Republican leaders won the votes of Western senators through passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act and other concessions, and Harrison signed the McKinley Tariff into law in October 1890.

The Harrison administration negotiated more than a dozen reciprocity agreements with European and Latin American nations in an attempt to expand U.S. trade. Even with the reductions and reciprocity, the McKinley Tariff enacted the highest average rate in American history, and the spending associated with it contributed to the reputation of the " Billion-Dollar Congress".

Currency

One of the most volatile questions of the 1880s was whether the currency should be backed by gold and silver, or by gold alone. Owing to worldwidedeflation

In economics, deflation is a decrease in the general price level of goods and services. Deflation occurs when the inflation rate falls below 0% (a negative inflation rate). Inflation reduces the value of currency over time, but sudden deflatio ...

in the late 19th century, a strict gold standard had resulted in reduction of incomes without the equivalent reduction in debts, pushing debtors and the poor to call for silver coinage as an inflationary measure. Because silver was worth less than its legal equivalent in gold, taxpayers paid their government bills in silver, while international creditors demanded payment in gold, resulting in a depletion of the nation's gold supply. The issue cut across party lines, with western Republicans and southern Democrats joining together in the call for the free coinage of silver, and both parties' representatives in the northeast holding firm for the gold standard.

The silver coinage issue had not been much discussed in the 1888 campaign. Harrison attempted to steer a middle course between the two positions, advocating a free coinage of silver, but at its own value, not at a fixed ratio to gold. Congress did not adopt Harrison's proposal, but in July 1890, Senator Sherman won passage of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act was a United States federal law

enacted on July 14, 1890.Charles Ramsdell Lingley, ''Since the Civil War'', first edition: New York, The Century Co., 1920, ix–635 p., . Re-issued: Plain Label Books, unknown date, ...

. The Sherman Silver Purchase Act increased the amount of silver the government was required to purchase on a recurrent monthly basis to 4.5 million ounces. Believing that the bill would end the controversy over silver, Harrison signed the bill into law. The effect of the bill, however, was the increased depletion of the nation's gold supply, a problem that would persist until after Harrison left office. The bill and the silver debate also split the Republican Party, leading to the rise of the Silver Republicans, an influential bloc of Western Congressmen who backed the free coinage of silver. Many of these Silver Republicans would later join the Democratic Party.

Civil service reform and pensions

Civil service

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil servants hired on professional merit rather than appointed or elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leaders ...

reform was a prominent issue following Harrison's election. Harrison had campaigned as a supporter of the merit system The merit system is the process of promoting and hiring government employees based on their ability to perform a job, rather than on their political connections. It is the opposite of the spoils system.

History

The earliest known example of a me ...

, as opposed to the spoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a reward ...

. Although the passage of the 1883 Pendleton Act

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act is a United States federal law passed by the 47th United States Congress and signed into law by President Chester A. Arthur on January 16, 1883. The act mandates that most positions within the federal govern ...

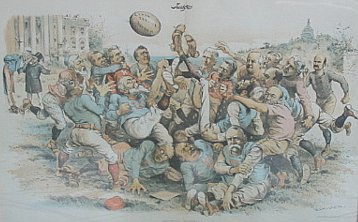

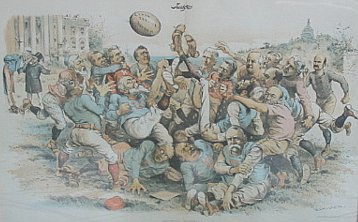

had decreased the role of patronage in assigning government positions, Harrison spent much of his first months in office deciding on political appointments. Congress was severely divided on civil service reform and Harrison was reluctant to address the issue for fear of alienating either side. The issue became a political football

A political football is a topic or issue that is seized on by opposing political parties or factions and made a more political issue than it might initially seem to be. "To make a political football" ut of somethingis defined in William Safire' ...

of the time and was immortalized in a cartoon captioned "What can I do when both parties insist on kicking?" Harrison appointed Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

and Hugh Smith Thompson, both reformers, to the Civil Service Commission

A civil service commission is a government agency that is constituted by legislature to regulate the employment and working conditions of civil servants, oversee hiring and promotions, and promote the values of the public service. Its role is rough ...

, but otherwise did little to further the reform cause. Harrison largely ignored Roosevelt, who frequently called for an expansion of the merit system and complained about the administration of Postmaster General Wanamaker.

Harrison's solution to the growing surplus in the federal treasury was to increase pensions for Civil War veterans, the great majority of whom were Republicans. He presided over the enactment of the Dependent and Disability Pension Act, a cause he had championed while in Congress. In addition to providing pensions to disabled Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policie ...

veterans (regardless of the cause of their disability), the act depleted some of the troublesome federal budget surplus. Pension expenditures reached $135 million under Harrison, the largest expenditure of its kind to that point in American history, a problem exacerbated by Pension Bureau The Bureau of Pensions was an agency of the federal government of the United States which existed from 1832 to 1930. It originally administered pensions solely for military personnel. Pension duties were transferred to the United States Department o ...

commissioner James R. Tanner's expansive interpretation of the pension laws. An investigation into the Pension Bureau by Secretary of the Interior Noble found evidence of lavish and illegal handouts under Tanner. Harrison, who privately believed that appointing Tanner had been a mistake due to his apparent loose management style and tongue, asked Tanner to resign and replaced him with Green B. Raum. Raum was also accused of accepting loan payments in return for expediting pension cases, but Harrison, having accepted a dissenting Congressional Republican investigation report that exonerated Raum, kept him in office for the rest of his administration.

Civil rights

In violation of the Fifteenth Amendment, many Southern states denied African-Americans the right to vote. Convinced that the "lily-white policy" of attempting to attract white Southerners to the Republican Party had failed, and believing that the disenfranchisement of African-American voters was immoral, Harrison endorsed the Federal Elections Bill. The bill, written by Representative

In violation of the Fifteenth Amendment, many Southern states denied African-Americans the right to vote. Convinced that the "lily-white policy" of attempting to attract white Southerners to the Republican Party had failed, and believing that the disenfranchisement of African-American voters was immoral, Harrison endorsed the Federal Elections Bill. The bill, written by Representative Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy ...

and Senator George Frisbie Hoar

George Frisbie Hoar (August 29, 1826 – September 30, 1904) was an American attorney and politician who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1877 to 1904. He belonged to an extended family that became politically promi ...

, would have provided federal oversight over elections for the U.S. House of Representatives. Southern opponents of the bill labeled it the "Force Bill," claiming that it would allow the U.S. Army to enforce voting rights, although the law did not contain such a provision. The bill passed the House in July 1890 on a largely party-line vote, but a vote on the bill was delayed in the Senate after Republican leaders chose to focus on the tariff and other priorities. In January 1891, the Senate voted 35–34 to table consideration of the Federal Elections Bill in favor of an unrelated bill backed by the Silver Republicans, and the bill never passed. While many Republicans had supported the Federal Elections Bill, it faced opposition from city-machine party bosses who feared oversight in their own wards; other Republicans were willing to sacrifice the bill to focus on other priorities. The bill represented the last significant federal attempt to protect African-American civil rights until the 1930s, and its failure allowed Southern states to pass Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

, resulting in the near-complete disenfranchisement of Southern blacks.

Following the failure to pass the bill, Harrison continued to speak in favor of African American civil rights in addresses to Congress. Attorney General Miller conducted prosecutions for violation of voting rights in the South, but white juries often refused to convict or indict violators. He argued that if the states have authority over civil rights, then "we have a right to ask whether they are at work upon it." Harrison also supported a bill proposed by Senator Henry W. Blair

Henry William Blair (December 6, 1834March 14, 1920) was a United States representative and Senator from New Hampshire. During the American Civil War, he was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Union Army.

A Radical Republican in his earlier political ...

, which would have granted federal funding to schools regardless of the students' races. Though similar bills had garnered strong Republican support during the 1880s, Blair's bill was defeated in the Senate in 1890 after several Republicans voted against it. Harrison also endorsed an unsuccessful constitutional amendment to overturn the Supreme Court's holding in the ''Civil Rights Cases

The ''Civil Rights Cases'', 109 U.S. 3 (1883), were a group of five landmark cases in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments did not empower Congress to outlaw racial discrimination by p ...

'', which had declared much of the Civil Rights Act of 1875

The Civil Rights Act of 1875, sometimes called the Enforcement Act or the Force Act, was a United States federal law enacted during the Reconstruction era in response to civil rights violations against African Americans. The bill was passed by the ...

unconstitutional, but no action was taken on such an amendment.

1890 midterm elections

By the end of the 51st Congress, Harrison and the Republican-controlled allies had passed one of the most ambitious peacetime domestic legislative programs in U.S. history, but the results of the 1890 elections brought the pace of legislation to a sudden halt. Republicans lost almost 100 seats in the House of Representatives, and DemocratCharles Frederick Crisp

Charles Frederick Crisp (January 29, 1845 – October 23, 1896) was a United States political figure. A Democrat, he was elected as a congressman from Georgia in 1882, and served until his death in 1896. From 1890 until his death, he led the Dem ...

replaced Thomas Brackett Reed

Thomas Brackett Reed (October 18, 1839 – December 7, 1902) was an American politician from the state of Maine. A member of the Republican Party, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives 12 times, first in 1876, and serve ...

as Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hunger ...

. However, Republicans defended their Senate majority. The 1890 elections also saw the rise of the Populist Party, a third party

Third party may refer to:

Business

* Third-party source, a supplier company not owned by the buyer or seller

* Third-party beneficiary, a person who could sue on a contract, despite not being an active party

* Third-party insurance, such as a Veh ...

consisting of farmers in the South and Midwest. The Populists emerged from the Farmers' Alliance

The Farmers' Alliance was an organized agrarian economic movement among American farmers that developed and flourished ca. 1875. The movement included several parallel but independent political organizations — the National Farmers' Alliance and ...

, the Knights of Labor

Knights of Labor (K of L), officially Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, was an American labor federation active in the late 19th century, especially the 1880s. It operated in the United States as well in Canada, and had chapters also ...

, and other agrarian reform movements. The party favored bimetallism, the restoration of the Greenback, the nationalization of telegraphs and railroads, tax reform, the abolition of national banks, and other policies. The party's newfound popularity was driven in part by opposition to the McKinley Tariff, which many regarded as benefiting industrialists at the expense of other groups. Many Populists in the Midwest left the Republican Party, while in the South, Populist-aligned candidates generally remained part of the Democratic Party. The split of the Republican vote allowed for the rise of Democrats in the Midwest, including future presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

of Nebraska.

National forests

In March 1891 Congress enacted and Harrison signed theLand Revision Act of 1891

The General Revision Act (sometimes Land Revision Act) of 1891, also known as the Forest Reserve Act of 1891, was a federal law signed in 1891 by President Benjamin Harrison. The Act reversed previous policy initiatives, such as the Timber Culture ...

. This legislation resulted from a bipartisan desire to initiate reclamation of surplus lands that had been, up to that point, granted from the public domain, for potential settlement or use by railroad syndicates. As the law's drafting was finalized, Section 24 was added at the behest of Harrison by his Secretary of the Interior John Noble, which read as follows:

That the President of the United States may, from time to time, set apart and reserve, in any State or Territory having public land bearing forests, in any part of the public lands wholly or in part covered with timber or undergrowth, whether of commercial value or not, as public reservations, and the President shall, by public proclamation, declare the establishment of such reservations and the limits thereof.Within a month of the enactment of this law Harrison authorized the first forest reserve, to be located on public domain adjacent to Yellowstone Park, in Wyoming. Other areas were so designated by Harrison, bringing the first forest reservations total to 22 million acres in his term. Harrison was also the first to give a prehistoric Indian Ruin, Casa Grande in Arizona, federal protection.

Native American policy

During Harrison's administration, the Lakota Sioux, previously confined to reservations in South Dakota, grew restive under the influence ofWovoka

Wovoka (c. 1856 - September 20, 1932), also known as Jack Wilson, was the Paiute religious leader who founded a second episode of the Ghost Dance movement. Wovoka means "cutter" or "wood cutter" in the Northern Paiute language.

Biography

Wovok ...

, a medicine man, who encouraged them to participate in a spiritual movement called the Ghost Dance

The Ghost Dance (Caddo: Nanissáanah, also called the Ghost Dance of 1890) was a ceremony incorporated into numerous Native American belief systems. According to the teachings of the Northern Paiute spiritual leader Wovoka (renamed Jack Wilson ...

. Many in Washington did not understand the predominantly religious nature of the Ghost Dance, and thought it was a militant movement being used to rally Native Americans against the government. In reality, however, there were only about 4,200 ghost dancers, most of whom were women, children, and the elderly. In November 1890, Harrison himself ordered troops to Pine Ridge in order to prevent "any outbreak that may put in peril the lives and homes of the settlers of the adjacent states". The arrival of troops increased tensions on both sides, and the natives felt threatened. On December 29, 1890, troops from the Seventh Cavalry clashed with the Sioux at Wounded Knee. The result was a massacre of at least 146 Sioux, including many women and children; the dead Sioux were buried in a mass grave. In reaction Harrison directed Major General Nelson A. Miles

Nelson Appleton Miles (August 8, 1839 – May 15, 1925) was an American military general who served in the American Civil War, the American Indian Wars, and the Spanish–American War.

From 1895 to 1903, Miles served as the last Commanding G ...

to investigate and ordered 3500 federal troops to South Dakota; the uprising was brought to an end. Afterwards, Harrison would honor the 7th Cavalry, and 20 soldiers received medals for their role in the massacre. Wounded Knee is considered the last major American Indian battle in the 19th century. Harrison's general policy on American Indians was to encourage assimilation into white society and, despite the massacre, he believed the policy to have been generally successful. This policy, known as the allotment system

The allotment system ( sv, indelningsverket; fi, ruotujakolaitos) was a system used in Sweden for keeping a trained army at all times. This system came into use in around 1640, and was replaced by the modern Swedish Armed Forces conscription s ...

and embodied in the Dawes Act

The Dawes Act of 1887 (also known as the General Allotment Act or the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887) regulated land rights on tribal territories within the United States. Named after Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts, it authorized the Pre ...

, was favored by liberal reformers at the time, but eventually proved detrimental to American Indians as they sold most of their land at low prices to white speculators.

Soon after taking office, Harrison signed an appropriations bill that opened parts of Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign i ...

to white settlement. The territory had been established earlier in the 19th century for the resettlement of the "Five Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cre ...

," and portions of the territory known as the Unassigned Lands

The Unassigned Lands in Oklahoma were in the center of the lands ceded to the United States by the Creek (Muskogee) and Seminole Indians following the Civil War and on which no other tribes had been settled. By 1883 it was bounded by the Chero ...

had not yet been granted to any tribe. In the Land Rush of 1889

The Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889 was the first land run into the Unassigned Lands of former Indian Territory, which had earlier been assigned to the Creek and Seminole peoples. The area that was opened to settlement included all or part of Canadi ...

, 50,000 settlers moved into the Unassigned Lands to establish land claims. In the 1890 Oklahoma Organic Act

An Organic Act is a generic name for a statute used by the United States Congress to describe a territory, in anticipation of being admitted to the Union as a state. Because of Oklahoma's unique history (much of the state was a place where aborig ...

, Oklahoma Territory

The Territory of Oklahoma was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 2, 1890, until November 16, 1907, when it was joined with the Indian Territory under a new constitution and admitted to the Union as th ...

was created out of the western half of Indian Territory.

Federal immigration control and Ellis Island

In 1890, President Harrison approved the assumption of federal control over immigration, ending the previous policy of leaving it to the states to regulate. Further, in 1891, he signed into law the Immigration Act of March 3, creating a federal immigration agency in the Treasury Department, establishing regulations on the type of aliens to be admitted and those for whom admission was to be barred, and funding the construction of the first federal immigration station onEllis Island

Ellis Island is a federally owned island in New York Harbor, situated within the U.S. states of New York and New Jersey, that was the busiest immigrant inspection and processing station in the United States. From 1892 to 1954, nearly 12 mill ...

, in New York harbor, the nation's busiest port for arriving immigrants. Funding also provided for smaller immigration facilities at other port cities, including Boston, Philadelphia and Baltimore.

Technology and military modernization

During Harrison's time in office, the United States was continuing to experience advances in science and technology, and Harrison was the earliest president whose voice is known to be preserved. That was originally made on a wax

During Harrison's time in office, the United States was continuing to experience advances in science and technology, and Harrison was the earliest president whose voice is known to be preserved. That was originally made on a wax phonograph cylinder

Phonograph cylinders are the earliest commercial medium for recording and reproducing sound. Commonly known simply as "records" in their era of greatest popularity (c. 1896–1916), these hollow cylindrical objects have an audio recording engra ...

in 1889 by Gianni Bettini. Harrison also had electricity installed in the White House for the first time by Edison General Electric Company

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as Electricity generation, electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and Motion p ...

, but he and his wife would not touch the light switches for fear of electrocution and would often go to sleep with the lights on.

The United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage of ...

fell into obsolescence following the Civil War, though reform and expansion had begun under President Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 21st president of the United States from 1881 to 1885. He previously served as the 20th vice president under President James A ...

. When Harrison took office there were only two commissioned warships in the Navy. In his inaugural address he said, "construction of a sufficient number of warships and their necessary armaments should progress as rapidly as is consistent with care and perfection." Harrison's support for naval expansion was aided and encouraged by several naval officers, who argued that the navy would be useful for protecting American trade projecting American power. In 1890, Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan

Alfred Thayer Mahan (; September 27, 1840 – December 1, 1914) was a United States naval officer and historian, whom John Keegan called "the most important American strategist of the nineteenth century." His book '' The Influence of Sea Powe ...

published ''The Influence of Sea Power upon History

''The Influence of Sea Power upon History: 1660–1783'' is a history of naval warfare published in 1890 by the American naval officer and historian Alfred Thayer Mahan. It details the role of sea power during the seventeenth and eighteenth cent ...

'', an influential work of naval strategy that called for naval expansion; Harrison strongly endorsed it, and Mahan was restored to his position of President of the Naval War College

The president of the Naval War College is a flag officer in the United States Navy. The President's House, Naval War College, President's House in Newport, Rhode Island is their official residence.

The office of the president was created along ...

. Secretary of the Navy Tracy spearheaded the rapid construction of vessels, and within a year congressional approval was obtained for building of the warships , , and . By 1898, with the help of the Carnegie Corporation, no less than ten modern warships, including steel hulls and greater displacements and armaments, had transformed the United States into a legitimate naval power. Seven of these had begun during the Harrison term.

The United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

had also been largely neglected since the Civil War, despite the continuing American Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

. When Harrison took office, there were roughly 28,000 officers and enlisted men, and much of the equipment was inferior to that of European armies. Secretary of War Proctor sought to institute several reforms, including an improved diet and the granting of furlough

A furlough (; from nl, verlof, "leave of absence") is a temporary leave of employees due to special needs of a company or employer, which may be due to economic conditions of a specific employer or in society as a whole. These furloughs may be s ...

s, resulting in a decline of the desertion rate. Promotions for officers began to be granted based on the branch of service rather than on a regimental basis, and those subject to promotion were required to pass examinations. The Harrison administration also re-established the position of United States Assistant Secretary of War

The United States Assistant Secretary of War was the second–ranking official within the American United States Department of War, Department of War from 1861 to 1867, from 1882 to 1883, and from 1890 to 1940. According to thMilitary Laws of the U ...

to serve as the second-ranking member of the War Department. Harrison's reform efforts halved the desertion rate, but otherwise the army remained in largely the same state at the end of his tenure.

Standardization of place names

By executive order, Harrison established the Board on Geographical Names in 1890. The board was tasked with standardizing the spelling of the names of communities and municipalities within the United States; most towns withapostrophe

The apostrophe ( or ) is a punctuation mark, and sometimes a diacritical mark, in languages that use the Latin alphabet and some other alphabets. In English, the apostrophe is used for two basic purposes:

* The marking of the omission of one o ...

s or plurals as part of their names were rewritten as singular (e.g. Weston's Mills became Weston Mills) and places that ended in "burgh" were truncated to end in "burg." In one particularly controversial case, a city in Pennsylvania was shortened from Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsylv ...

to Pittsburg, only to reverse the decision 20 years later after local residents continued to use the "Pittsburgh" spelling.

Foreign policy

Harrison appreciated the forces of nationalism and imperialism which were inevitably pulling the United States onward into playing a more important part in world affairs as it grew rapidly in financial and economic prowess. While the ineffective diplomatic corps was still mired in patronage, the rapidly growing consular service vigorously promoted commerce abroad. In a speech in 1891, Harrison proclaimed that the United States was in a "new epoch" of trade and that the expanding navy would protect oceanic shipping and increase American influence and prestige abroad. The increasing importance of the United States in world affairs was reflected in the act of Congress in 1893 which raised the rank of the most important diplomatic representatives abroad from minister plenipotentiary to ambassador.Latin America

Harrison and Blaine agreed on an ambitious foreign policy that emphasized commercial reciprocity with other nations. Their goal was to replace Britain as the dominant commercial power inLatin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

. The First International Conference of American States

The First International Conference of American States was held in Washington, D.C., United States, from 20 January to 27 April 1890.

Background to the Conference

The idea of an Inter-American Conference held in Washington, D.C., was the brainch ...

met in Washington in 1889; Harrison set an aggressive agenda including customs and currency integration and named a bipartisan conference delegation led by John B. Henderson and Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans in ...

. Though the conference failed to achieve any diplomatic breakthrough, it did succeed in establishing an information center that became the Pan American Union

The Organization of American States (OAS; es, Organización de los Estados Americanos, pt, Organização dos Estados Americanos, french: Organisation des États américains; ''OEA'') is an international organization that was founded on 30 April ...

. In response to the diplomatic bust, Harrison and Blaine pivoted diplomatically and initiated a crusade for tariff reciprocity with Latin American nations; the Harrison administration concluded eight reciprocity treaties among these countries. The Harrison administration did not pursue reciprocity with Canada, as Harrison and Blaine believed that Canada was an integral part of the British economic bloc and could never be integrated into a trade system dominated by the U.S. On another front, Harrison sent Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

as ambassador to Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and s ...

, but failed in his attempts to establish a naval base there.

Samoa

By 1889, the United States, Great Britain and Germany were locked in an escalating dispute over control of theSamoan Islands

The Samoan Islands ( sm, Motu o Sāmoa) are an archipelago covering in the central South Pacific, forming part of Polynesia and of the wider region of Oceania. Administratively, the archipelago comprises all of the Independent State of Samoa ...

in the Pacific. The dispute had started in 1887 when the Germans tried to establish control over the island chain and President Cleveland responded by sending three naval vessels to defend the Samoan government. American and German warships faced off but all were badly damaged by the 1889 Apia cyclone

The 1889 Apia cyclone was a tropical cyclone in the South Pacific Ocean, which swept across Apia, Samoa on March 15, 1889, during the Samoan crisis. The effect on shipping in the harbour was devastating, largely because of what has been described ...

of March 15–17, 1889. Seeking to improve relations with Britain and the United States, German Chancellor Otto Von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of ...