Presbyterian Church In The United States Of America on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (PCUSA) was the first national

The origins of the

The origins of the

The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw Americans leaving the Eastern Seaboard to settle further inland. One of the results was that the PCUSA signed a Plan of Union with the

The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw Americans leaving the Eastern Seaboard to settle further inland. One of the results was that the PCUSA signed a Plan of Union with the  Growth in the Northeast was accompanied by the creation of moral reform organizations, such as

Growth in the Northeast was accompanied by the creation of moral reform organizations, such as

Another major stimulus for growth was the

Another major stimulus for growth was the

Heresy trials of prominent New School leaders further deepened the division within the denomination. Both the Presbytery and Synod of Philadelphia found Albert Barnes, pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, guilty of heresy. Old School Presbyterians, however, were outraged when the New School dominated General Assembly of 1831 dismissed the charges. Lyman Beecher, famous revivalist, moral reformer and president of the newly established

Heresy trials of prominent New School leaders further deepened the division within the denomination. Both the Presbytery and Synod of Philadelphia found Albert Barnes, pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, guilty of heresy. Old School Presbyterians, however, were outraged when the New School dominated General Assembly of 1831 dismissed the charges. Lyman Beecher, famous revivalist, moral reformer and president of the newly established  The Old School faction was convinced that the Plan of Union with the Congregational churches had undermined Presbyterian doctrine and order. At the 1837 General Assembly, the Old School majority successfully passed resolutions removing all judicatories found under the Plan from the Presbyterian Church. In total, three synods in New York and one synod in Ohio along with 28 presbyteries, 509 ministers, and 60 thousand church members (one-fifth of the PCUSA's membership) were excluded from the church. New School leaders reacted by meeting in Auburn, New York, and issuing the Auburn Declaration, a 16-point defense of their Calvinist orthodoxy.

When the General Assembly met in May 1838 at Philadelphia, the New School commissioners attempted to be seated but were forced to leave and convene their own General Assembly elsewhere in the city. The Old School and New School factions had finally split into two separate churches that were about equal in size. Both churches, however, claimed to be the Presbyterian Church in the USA. The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania decided that the Old School body was the legal successor of the undivided PCUSA.

The Old School faction was convinced that the Plan of Union with the Congregational churches had undermined Presbyterian doctrine and order. At the 1837 General Assembly, the Old School majority successfully passed resolutions removing all judicatories found under the Plan from the Presbyterian Church. In total, three synods in New York and one synod in Ohio along with 28 presbyteries, 509 ministers, and 60 thousand church members (one-fifth of the PCUSA's membership) were excluded from the church. New School leaders reacted by meeting in Auburn, New York, and issuing the Auburn Declaration, a 16-point defense of their Calvinist orthodoxy.

When the General Assembly met in May 1838 at Philadelphia, the New School commissioners attempted to be seated but were forced to leave and convene their own General Assembly elsewhere in the city. The Old School and New School factions had finally split into two separate churches that were about equal in size. Both churches, however, claimed to be the Presbyterian Church in the USA. The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania decided that the Old School body was the legal successor of the undivided PCUSA.

The Synod of Philadelphia and New York had expressed moderate

The Synod of Philadelphia and New York had expressed moderate  In response, representatives of Old School presbyteries in the South met in December at Augusta, Georgia, to form the Presbyterian Church in the

In response, representatives of Old School presbyteries in the South met in December at Augusta, Georgia, to form the Presbyterian Church in the

In the decades after the reunion of 1869, conservatives expressed fear over the threat of " broad churchism" and modernist theology. Such fears were prompted in part by heresy trials (such as the 1874 acquittal of popular Chicago preacher

In the decades after the reunion of 1869, conservatives expressed fear over the threat of " broad churchism" and modernist theology. Such fears were prompted in part by heresy trials (such as the 1874 acquittal of popular Chicago preacher

Briggs' heresy trial was a setback to the movement for confessional revision, which wanted to soften the Westminster Confession's Calvinistic doctrines of predestination and

Briggs' heresy trial was a setback to the movement for confessional revision, which wanted to soften the Westminster Confession's Calvinistic doctrines of predestination and

Between 1922 and 1936, the PCUSA became embroiled in the so-called Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy. Tensions had been building in the years following the Old School-New School reunion of 1869 and the Briggs heresy trial of 1893. In 1909, the conflict was further exacerbated when the Presbytery of New York granted licenses to preach to a group of men who could not affirm the virgin birth of Jesus. The presbytery's action was appealed to the 1910 General Assembly, which then required all ministry candidates to affirm five essential or fundamental tenets of the Christian faith: biblical inerrancy, the virgin birth,

Between 1922 and 1936, the PCUSA became embroiled in the so-called Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy. Tensions had been building in the years following the Old School-New School reunion of 1869 and the Briggs heresy trial of 1893. In 1909, the conflict was further exacerbated when the Presbytery of New York granted licenses to preach to a group of men who could not affirm the virgin birth of Jesus. The presbytery's action was appealed to the 1910 General Assembly, which then required all ministry candidates to affirm five essential or fundamental tenets of the Christian faith: biblical inerrancy, the virgin birth,  In 1929, Princeton Theological Seminary was reorganized to make the school's leadership and faculty more representative of the wider church rather than just Old School Presbyterianism. Two of the seminary's new board members were signatories to the Auburn Affirmation. In order to preserve Princeton's Old School legacy, Machen and several of his colleagues founded Westminster Theological Seminary.

Further controversy would erupt over the state of the church's missionary efforts. Sensing a loss of interest and support for foreign missions, the nondenominational Laymen's Foreign Mission Inquiry published '' Re-Thinking Missions: A Laymen's Inquiry after One Hundred Years'' in 1932, which promoted universalism and rejected the uniqueness of Christianity. Because the Inquiry had been initially supported by the PCUSA, many conservatives were concerned that ''Re-Thinking Missions'' represented the views of PCUSA's Board of Foreign Missions. Even after board members affirmed their belief in "Jesus Christ as the only Lord and Saviour", some conservatives remained skeptical, and such fears were reinforced by modernist missionaries, including celebrated author Pearl S. Buck. While initially evangelical, Buck's religious views developed over time to deny the divinity of Christ.

In 1933, Machen and other conservatives founded the

In 1929, Princeton Theological Seminary was reorganized to make the school's leadership and faculty more representative of the wider church rather than just Old School Presbyterianism. Two of the seminary's new board members were signatories to the Auburn Affirmation. In order to preserve Princeton's Old School legacy, Machen and several of his colleagues founded Westminster Theological Seminary.

Further controversy would erupt over the state of the church's missionary efforts. Sensing a loss of interest and support for foreign missions, the nondenominational Laymen's Foreign Mission Inquiry published '' Re-Thinking Missions: A Laymen's Inquiry after One Hundred Years'' in 1932, which promoted universalism and rejected the uniqueness of Christianity. Because the Inquiry had been initially supported by the PCUSA, many conservatives were concerned that ''Re-Thinking Missions'' represented the views of PCUSA's Board of Foreign Missions. Even after board members affirmed their belief in "Jesus Christ as the only Lord and Saviour", some conservatives remained skeptical, and such fears were reinforced by modernist missionaries, including celebrated author Pearl S. Buck. While initially evangelical, Buck's religious views developed over time to deny the divinity of Christ.

In 1933, Machen and other conservatives founded the

Presbyterian Historical Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:Presbyterian Church in the United States of America 1789 establishments in Pennsylvania Orthodox Presbyterian Church Presbyterian Church (USA) predecessor churches Presbyterian denominations in the United States Presbyterian organizations established in the 18th century Protestant denominations established in the 18th century Religious organizations established in 1789

Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

denomination in the United States, existing from 1789 to 1958. In that year, the PCUSA merged with the United Presbyterian Church of North America

The United Presbyterian Church of North America (UPCNA) was an American Presbyterian denomination that existed for one hundred years. It was formed on May 26, 1858 by the union of the Northern branch of the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church ...

, a denomination with roots in the Seceder and Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from '' Covena ...

traditions of Presbyterianism. The new church was named the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America

The United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (UPCUSA) was the largest branch of Presbyterianism in the United States from May 28, 1958, to 1983. It was formed by the union of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of Ame ...

. It was a predecessor to the contemporary Presbyterian Church (USA)

The Presbyterian Church (USA), abbreviated PC(USA), is a mainline Protestant denomination in the United States. It is the largest Presbyterian denomination in the US, and known for its liberal stance on doctrine and its ordaining of women and ...

.

The denomination had its origins in colonial times when members of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

and Presbyterians from Ireland first immigrated to America. After the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, the PCUSA was organized in Philadelphia to provide national leadership for Presbyterians in the new nation. In 1861, Presbyterians in the Southern United States split from the denomination because of disputes over slavery, politics, and theology precipitated by the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. They established the Presbyterian Church in the United States

The Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS, originally Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America) was a Protestant denomination in the Southern and border states of the United States that existed from 1861 to 1983. That ye ...

, often simply referred to as the "Southern Presbyterian Church". Due to its regional identification, the PCUSA was commonly described as the Northern Presbyterian Church. Despite the PCUSA's designation as a "Northern church", it was once again a national denomination in its later years.

Over time, traditional Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

played less of a role in shaping the church's doctrines and practices—it was influenced by Arminianism

Arminianism is a branch of Protestantism based on the theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius (1560–1609) and his historic supporters known as Remonstrants. Dutch Arminianism was originally articulated in the ''Rem ...

and revivalism early in the 19th century, liberal theology

Religious liberalism is a conception of religion (or of a particular religion) which emphasizes personal and group liberty and rationality. It is an attitude towards one's own religion (as opposed to criticism of religion from a secular position ...

late in the 19th century, and neo-orthodoxy

In Christianity, Neo-orthodoxy or Neoorthodoxy, also known as theology of crisis and dialectical theology, was a theological movement developed in the aftermath of the First World War. The movement was largely a reaction against doctrines o ...

by the mid-20th century. The theological tensions within the denomination were played out in the Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy of the 1920s and 1930s, a conflict that led to the development of Christian fundamentalism

Christian fundamentalism, also known as fundamental Christianity or fundamentalist Christianity, is a religious movement emphasizing biblical literalism. In its modern form, it began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries among British and ...

and has historical importance to modern American evangelicalism. Conservatives dissatisfied with liberal trends left to form the Orthodox Presbyterian Church

The Orthodox Presbyterian Church (OPC) is a confessional Presbyterian denomination located primarily in the United States, with additional congregations in Canada, Bermuda, and Puerto Rico. It was founded by conservative members of the Presbyter ...

in 1936, and again, another conservative separation in 1973 resulting in the formation of the Presbyterian Church in America (PCA).

History

Colonial era

Early organization efforts (1650–1729)

The origins of the

The origins of the Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

Church is the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

of the 16th century. The writings of French theologian and lawyer John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

(1509–64) solidified much of the Reformed thinking that came before him in the form of the sermons and writings of Huldrych Zwingli. John Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgat ...

, a former Catholic priest from Scotland who studied with Calvin in Geneva, Switzerland

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

, took Calvin's teachings back to Scotland and led the Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke with the Pope, Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Church of Scotland, Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterianism, Presbyterian in ...

of 1560. As a result, the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

embraced Reformed theology and presbyterian polity

Presbyterian (or presbyteral) polity is a method of church governance ("ecclesiastical polity") typified by the rule of assemblies of presbyters, or elders. Each local church is governed by a body of elected elders usually called the session o ...

. The Ulster Scots brought their Presbyterian faith with them to Ireland, where they laid the foundation of what would become the Presbyterian Church of Ireland.

By the second half of the 17th century, Presbyterians were immigrating to British North America. Scottish and Scotch-Irish immigrants contributed to a strong Presbyterian presence in the Middle Colonies, particularly Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

."Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.)"Encyclopædia Britannica Online

An encyclopedia (American English) or encyclopædia (British English) is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge either general or special to a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into article ...

. Accessed May 29, 2014. Before 1706, however, Presbyterian congregations were not yet organized into presbyteries or synod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word '' synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin word mean ...

s.

In 1706, seven ministers led by Francis Makemie

Francis Makemie (1658–1708) was an Ulster Scots clergyman, considered to be the founder of Presbyterianism in the United States of America.

Early and family life

Makemie was born in Ramelton, County Donegal, Ireland (part of the Province o ...

established the first presbytery in North America, the Presbytery of Philadelphia

The Presbytery of Philadelphia, known during its early years simply as the Presbytery or the General Presbytery, is a presbytery of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). It was the first organized presbytery in what was to become the United States.

H ...

. The presbytery was primarily created to promote fellowship and discipline among its members and only gradually developed into a governing body. Initially, member congregations were located in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland. Further growth led to the creation of the Synod of Philadelphia (known as the "General Synod") in 1717. The synod's membership consisted of all ministers and one lay elder

An elder is someone with a degree of seniority or authority.

Elder or elders may refer to:

Positions Administrative

* Elder (administrative title), a position of authority

Cultural

* North American Indigenous elder, a person who has and ...

from every congregation.

The synod still had no official confessional statement. The Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

and the Irish Synod of Ulster The (General) Synod of Ulster was the forerunner of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland. It comprised all the clergy of the church elected by their respective local presbyteries (or church elders) and a section of the laity. ...

already required clergy to subscribe to the Westminster Confession

The Westminster Confession of Faith is a Reformed confession of faith. Drawn up by the 1646 Westminster Assembly as part of the Westminster Standards to be a confession of the Church of England, it became and remains the " subordinate standard ...

. In 1729, the synod passed the Adopting Act, which required clergy to assent to the Westminster Confession and Larger and Shorter Catechism

The Westminster Shorter Catechism is a catechism written in 1646 and 1647 by the Westminster Assembly, a synod of English and Scottish theologians and laymen intended to bring the Church of England into greater conformity with the Church of S ...

s. However, subscription was only required for those parts of the Confession deemed an "essential and necessary article of faith". Ministers could declare any scruples to their presbytery or the synod, which would then decide if the minister's views were acceptable. While crafted as a compromise, the Adopting Act was opposed by those who favored strict adherence to the Confession.

Old Side–New Side Controversy (1730–1758)

During the 1730s and 1740s, the Presbyterian Church was divided over the impact of theFirst Great Awakening

The First Great Awakening (sometimes Great Awakening) or the Evangelical Revival was a series of Christian revivals that swept Britain and its thirteen North American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s. The revival movement permanently affecte ...

. Drawing from the Scotch-Irish revivalist tradition, evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

ministers such as William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

and Gilbert Tennent

Gilbert Tennent (5 February 1703 – 23 July 1764) was a pietistic Protestant evangelist in colonial America. Born in a Presbyterian Scots-Irish family in County Armagh, Ireland, he migrated to America as a teenager, trained for pastoral mini ...

emphasized the necessity of a conscious conversion experience and the need for higher moral standards among the clergy.

Other Presbyterians were concerned that revivalism presented a threat to church order. In particular, the practice of itinerant preaching across presbytery boundaries and the tendency of revivalists to doubt the conversion experiences of other ministers caused controversy between supporters of revivalism, known as the "New Side", and their conservative opponents, known as the "Old Side". While the Old Side and New Side disagreed over the possibility of immediate assurance of salvation, the controversy was not primarily theological. Both sides believed in justification by faith, predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby ...

, and that regeneration occurred in stages.

In 1738, the synod moved to restrict itinerant preaching and to tighten educational requirements for ministers, actions the New Side resented. Tensions between the two sides continued to escalate until the Synod of May 1741, which ended with a definite split between the two factions. The Old Side retained control of the Synod of Philadelphia, and it immediately required unconditional subscription to the Westminster Confession with no option to state scruples. The New Side founded the Synod of New York. The new Synod required subscription to the Westminster Confession in accordance with the Adopting Act, but no college degrees were required for ordination.

While the controversy raged, American Presbyterians were also concerned with expanding their influence. In 1740, a New York Board of the Society in Scotland for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge was established. Four years later, David Brainerd was assigned as a missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

to the Native Americans. New Side Presbyterians were responsible for founding Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

(originally the College of New Jersey) primarily to train ministers in 1746.

By 1758, both sides were ready for reconciliation. Over the years, New Side revivalism had become less radical. At the same time, Old Side Presbyterians were experiencing numerical decline and were eager to share in the New Side's vitality and growth. The two synods merged to become the Synod of New York and Philadelphia. The united Synod was founded on New Side terms: subscription according to the terms of the Adopting Act; presbyteries were responsible for examining and licensing ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform ...

candidates; candidates were to be examined for learning, orthodoxy and their "experimental acquaintance with religion" (i.e. their personal conversion experiences); and revivals were acknowledged as a work of God.

American Independence (1770–1789)

In the early 1770s, American Presbyterians were initially reluctant to support American Independence, but in time many Presbyterians came to support the Revolutionary War. After theBattles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, ...

, the Synod of New York and Philadelphia published a letter in May 1775 urging Presbyterians to support the Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

while remaining loyal to George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

. In one sermon, John Witherspoon, president of Princeton, preached "that the cause in which America is now in arms, is the cause of justice, of liberty, and of human nature". Witherspoon and 11 other Presbyterians were signatories to the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

.

Even before the war, many Presbyterian felt that the single synod system was no longer adequate to meet the needs of a numerically and geographically expanding church. All clergy were supposed to attend annual meetings of the synod, but some years attendance was less than thirty percent. In 1785, a proposal for the creation of a General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of pres ...

went before the synod, and a special committee was formed to draw up a plan of government.

Under the plan, the old synod was divided into four new synods all under the authority of the General Assembly. The synods were New York and New Jersey, Philadelphia, Virginia, and the Carolinas. Compared to the Church of Scotland, the plan gave presbyteries more power and autonomy. Synods and the General Assembly were to be "agencies for unifying the life of the Church, considering appeals, and promoting the general welfare of the Church as a whole." The plan included provisions from the Church of Scotland's Barrier Act of 1697, which required the General Assembly to receive the approval of a majority of presbyteries before making major changes to the church's constitution and doctrine. The constitution included the Westminster Confession of Faith, together with the Larger and Shorter Catechisms, as the church's subordinate standard

A subordinate standard is a Reformed confession of faith, catechism or other doctrinal or regulatory statement subscribed to by a Protestant church, setting out key elements of religious belief and church governance. It is ''subordinate'' to the ...

(i.e. subordinate to the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus ...

) in addition to the (substantially altered) Westminster Directory. The Westminster Confession was modified to bring its teaching on civil government in line with American practices.

In 1787, the plan was sent to the presbyteries for ratification. The synod held its last meeting in May 1788. The first General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America met in Philadelphia in May 1789. At that time, the church had four synods, 16 presbyteries, 177 ministers, 419 congregations and an estimated membership of 18,000.

19th century

Interdenominational societies

The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw Americans leaving the Eastern Seaboard to settle further inland. One of the results was that the PCUSA signed a Plan of Union with the

The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw Americans leaving the Eastern Seaboard to settle further inland. One of the results was that the PCUSA signed a Plan of Union with the Congregationalists

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs i ...

of New England in 1801, which formalized cooperation between the two bodies and attempted to provide adequate visitation and preaching for frontier congregations, along with eliminating rivalry between the two denominations. The large growth rate of the Presbyterian Church in the Northeast was in part due to the adoption of Congregationalist settlers along the western frontier.

Not unlike the circuit riders in the Episcopal and Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's ...

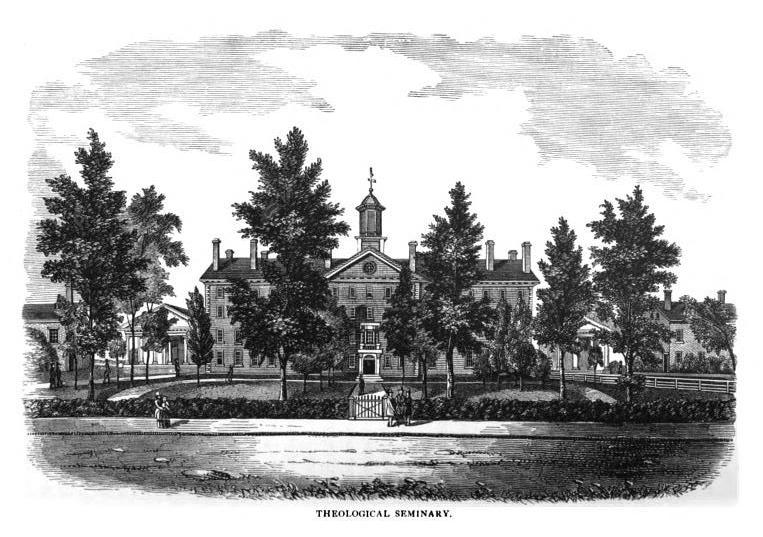

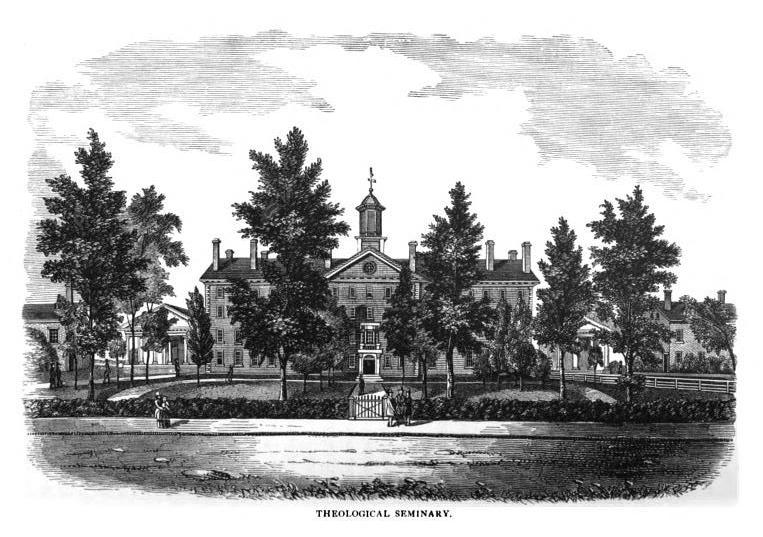

traditions, the presbyteries often sent out licentiates to minister in multiple congregations that were spread out over a wide area. To meet the need for educated clergy, Princeton Theological Seminary

Princeton Theological Seminary (PTSem), officially The Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church, is a private school of theology in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1812 under the auspices of Archibald Alexander, the General Assembly of t ...

and Union Presbyterian Seminary were founded in 1812, followed by Auburn Theological Seminary

Auburn Theological Seminary, located in New York City, teaches students about progressive social issues by offering workshops, providing consulting, and conducting research on faith leadership development.

The seminary was established in Auburn, N ...

in 1821.

Sunday school

A Sunday school is an educational institution, usually (but not always) Christian in character. Other religions including Buddhism, Islam, and Judaism have also organised Sunday schools in their temples and mosques, particularly in the West.

...

s, temperance

Temperance may refer to:

Moderation

*Temperance movement, movement to reduce the amount of alcohol consumed

*Temperance (virtue), habitual moderation in the indulgence of a natural appetite or passion

Culture

* Temperance (group), Canadian dan ...

associations, tract

Tract may refer to:

Geography and real estate

* Housing tract, an area of land that is subdivided into smaller individual lots

* Land lot or tract, a section of land

* Census tract, a geographic region defined for the purpose of taking a census

W ...

and Bible societies

A Bible society is a non-profit organization, usually nondenominational in makeup, devoted to translating, publishing, and distributing the Bible at affordable prices. In recent years they also are increasingly involved in advocating its credibi ...

, and orphanages. The proliferation of voluntary organizations was encouraged by postmillennialism, the belief that the Second Coming of Christ

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is a Christian (as well as Islamic and Baha'i) belief that Jesus will return again after his ascension to heaven about two thousand years ago. The idea is based on messia ...

would occur at the end of an era of peace and prosperity fostered by human effort. The 1815 General Assembly recommended the creation of societies to promote morality. Organizations such as the American Bible Society

American Bible Society is a U.S.-based Christian nonprofit headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. As the American member organization of United Bible Societies, it supports global Bible translation, production, distribution, literacy, engag ...

, the American Sunday School Union

InFaith has its roots in the First Day Society (founded 1790). InFaith officially formed in 1817 as the “Sunday and Adult School Union.” In 1824, the organization changed its name to American Sunday School Union (ASSU). Then, in 1974, the ASSU ...

, and the American Colonization Society, while theoretically interdenominational, were dominated by Presbyterians and considered unofficial agencies of the Presbyterian Church.

The support of missionary work was also a priority in the 19th century. The first General Assembly requested that each of the four synods appoint and support two missionaries. Presbyterians took leading roles in creating early local and independent mission societies, including the New York Missionary Society (1796), the Northern Berkshire and Columbia Missionary Societies (1797), the Missionary Society of Connecticut (1798), the Massachusetts Missionary Society (1799), and the Boston Female Society for Missionary Purposes (1800). The first denominational missions agency was the Standing Committee on Mission, which was created in 1802 to coordinate efforts with individual presbyteries and the European missionary societies. The work of the committee was expanded in 1816, becoming the Board of Missions.

In 1817, the General Assembly joined with two other Reformed denominations, the American branch of the Dutch Reformed Church (now the Reformed Church in America

The Reformed Church in America (RCA) is a mainline Reformed Protestant denomination in Canada and the United States. It has about 152,317 members. From its beginning in 1628 until 1819, it was the North American branch of the Dutch Reformed ...

) and the Associate Reformed Church

The Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church (ARPC), as it exists today, is the historical descendant of the Synod of the South, a Synod of the Associate Reformed Church. The original Associate Reformed Church resulted from a merger of the Associate ...

, to form the United Foreign Missionary Society. The United Society was particularly focused on work among Native Americans and inhabitants of Central and South America. These denominations also established a United Domestic Missionary Society to station missionaries within the United States.

In 1826, the Congregationalists joined these united efforts. The Congregational mission societies were merged with the United Domestic Missionary Society to become the American Home Missionary Society

The American Home Missionary Society (AHMS or A. H. M. Society) was a Protestant missionary society in the United States founded in 1826. It was founded as a merger of the United Domestic Missionary Society with state missionary societies from ...

. The Congregational American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was among the first American Christian missionary organizations. It was created in 1810 by recent graduates of Williams College. In the 19th century it was the largest and most imp ...

(ABCFM) became the recognized missions agency of the General Assembly, and the United Foreign Missionary Society's operations were merged with the American Board. By 1831, the majority of board members and missionaries of the ABCFM were Presbyterians. As a result, most of the local churches established by the organization were Presbyterian.

Second Great Awakening

Another major stimulus for growth was the

Another major stimulus for growth was the Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th century in the United States. The Second Great Awakening, which spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching, sparked a number of reform movements. R ...

(c. 1790 – 1840), which initially grew out of a 1787 student revival at Hampden–Sydney College

gr, Ye Shall Know the Truth

, established =

, type = Private liberal arts men's college

, religious_affiliation = Presbyterian Church (USA)

, endowment = $258 million (2021)

, president = Larry Stimpert

, city = Hampden Sydney, Virginia

, co ...

, a Presbyterian institution in Virginia. From there, revivals spread to Presbyterian churches in Virginia and then to North Carolina and Kentucky. The Revival of 1800 The Revival of 1800, also known as the Red River Revival, was a series of evangelical Christian meetings which began in Logan County, Kentucky. These ignited the subsequent events and influenced several of the leaders of the Second Great Awakening. ...

was one such revival that first grew out of meetings led by Presbyterian minister James McGready

Rev. James McGready (1763–1817) was a Presbyterian minister and a revivalist during the Second Great Awakening in the United States of America. He was one of the most important figures of the Second Great Awakening in the American frontier. ...

. The most famous camp meeting of the Second Great Awakening, the Cane Ridge Revival in Kentucky, occurred during a traditional Scottish communion season under the leadership of local Presbyterian minister Barton W. Stone

Barton Warren Stone (December 24, 1772 – November 9, 1844) was an American evangelist during the early 19th-century Second Great Awakening in the United States. First ordained a Presbyterian minister, he and four other ministers of the Washingt ...

. Over 10 thousand people came to Cane Ridge to hear sermons from Presbyterian as well as Methodist and Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

preachers.

Like the First Great Awakening, Presbyterian ministers were divided over their assessment of the fruits of the new wave of revivals. Many pointed to "excesses" displayed by some participants as signs that the revivals were theologically compromised, such as groans, laughter, convulsions and "jerks" (see religious ecstasy, holy laughter and slain in the Spirit). There was also concern over the tendency of revivalist ministers to advocate the free will

Free will is the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

Free will is closely linked to the concepts of moral responsibility, praise, culpability, sin, and other judgements which apply only to ac ...

teaching of Arminianism

Arminianism is a branch of Protestantism based on the theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius (1560–1609) and his historic supporters known as Remonstrants. Dutch Arminianism was originally articulated in the ''Rem ...

, thereby rejecting the Calvinist doctrines of predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby ...

.

Facing charges of heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important relig ...

for their Arminian beliefs, Presbyterian ministers Richard McNemar and John Thompson, along with Barton W. Stone and two other ministers, chose to withdraw from the Kentucky Synod and form the independent Springfield Presbytery

The Springfield Presbytery was an independent presbytery that became one of the earliest expressions of the Stone-Campbell Movement. It was composed of Presbyterian ministers who withdrew from the jurisdiction of the Kentucky Synod of the Presby ...

in 1803. These ministers would later dissolve the Springfield Presbytery and become the founders of the American Restoration Movement, from which the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) and Churches of Christ

The Churches of Christ is a loose association of autonomous Christian congregations based on the '' sola scriptura'' doctrine. Their practices are based on Bible texts and draw on the early Christian church as described in the New Testament.

...

denominations originate.

Meanwhile, the Cumberland Presbytery, also within the Kentucky Synod, faced a shortage of ministers and decided to license clergy candidates who were less educated than was typical and who could not subscribe completely to the Westminster Confession. In 1805, the synod suspended many of these ministers, even bringing heresy charges against a number of them, and by 1806 the synod had dissolved the presbytery. In 1810, ministers dissatisfied with the actions of the synod formed the Cumberland Presbyterian Church

The Cumberland Presbyterian Church is a Presbyterian denomination spawned by the Second Great Awakening. Matthew H. Gore, The History of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in Kentucky to 1988, (Memphis, Tennessee: Joint Heritage Committee, 2000) ...

(CPC). The CPC subscribed to a modified form of the Westminster Confession that rejected the Calvinist doctrines of double predestination and limited atonement.

Church growth in the Northeast was also accompanied by revivalism. While calmer and more reserved than those in the South, the revivals of the Second Great Awakening transformed religion in the Northeast, and they were often led by Presbyterians and Congregationalists. The Plan of Union led to the spread of New England theology

New England theology (or Edwardsianism) designates a school of theology which grew up among the Congregationalists of New England, originating in the year 1732, when Jonathan Edwards began his constructive theological work, culminating a little b ...

(also known as the New Divinity and New Haven theology

New England theology (or Edwardsianism) designates a school of theology which grew up among the Congregationalists of New England, originating in the year 1732, when Jonathan Edwards began his constructive theological work, culminating a little b ...

), originally conceived by Congregationalists. The New England theology modified and softened traditional Calvinism, rejecting the doctrine of imputation of Adam's sin, adopting the governmental theory of atonement, and embracing a greater emphasis on free will. It was essentially an attempt to construct a Calvinism conducive to revivalism. While the Synod of Philadelphia condemned the New Divinity as heretical in 1816, the General Assembly disagreed, concluding that New England theology did not conflict with the Westminster Confession.

Old School–New School Controversy

Notwithstanding the General Assembly's attempt to promote peace and unity, two distinct factions, the Old School and the New School, developed through the 1820s over the issues of confessional subscription, revivalism, and the spread of New England theology. The New School faction advocated revivalism and New England theology, while the Old School was opposed to the extremes of revivalism and desired strict conformity to the Westminster Confession. The ideological center of Old School Presbyterianism was Princeton Theological Seminary, which under the leadership ofArchibald Alexander

Archibald Alexander (April 17, 1772 – October 22, 1851) was an American Presbyterian theologian and professor at the Princeton Theological Seminary. He served for 9 years as the President of Hampden–Sydney College in Virginia and for 39 year ...

and Charles Hodge

Charles Hodge (December 27, 1797 – June 19, 1878) was a Reformed Presbyterian theologian and principal of Princeton Theological Seminary between 1851 and 1878.

He was a leading exponent of the Princeton Theology, an orthodox Calvinist theo ...

became associated with a brand of Reformed scholasticism known as Princeton Theology.

Heresy trials of prominent New School leaders further deepened the division within the denomination. Both the Presbytery and Synod of Philadelphia found Albert Barnes, pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, guilty of heresy. Old School Presbyterians, however, were outraged when the New School dominated General Assembly of 1831 dismissed the charges. Lyman Beecher, famous revivalist, moral reformer and president of the newly established

Heresy trials of prominent New School leaders further deepened the division within the denomination. Both the Presbytery and Synod of Philadelphia found Albert Barnes, pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, guilty of heresy. Old School Presbyterians, however, were outraged when the New School dominated General Assembly of 1831 dismissed the charges. Lyman Beecher, famous revivalist, moral reformer and president of the newly established Lane Theological Seminary

Lane Seminary, sometimes called Cincinnati Lane Seminary, and later renamed Lane Theological Seminary, was a Presbyterian theological college that operated from 1829 to 1932 in Walnut Hills, Ohio, today a neighborhood in Cincinnati. Its camp ...

, was charged with heresy in 1835 but was also acquitted.

The most radical figure in the New School faction was prominent evangelist Charles Grandison Finney. Finney's revivals were characterized by his "New Measures", which included protracted meetings, extemporaneous preaching, the anxious bench, and prayer groups. Albert Baldwin Dod accused Finney of preaching Pelagianism and urged him to leave the Presbyterian Church. Finney did just that in 1836 when he joined the Congregational church as pastor of the Broadway Tabernacle

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

in New York City.

The Old School faction was convinced that the Plan of Union with the Congregational churches had undermined Presbyterian doctrine and order. At the 1837 General Assembly, the Old School majority successfully passed resolutions removing all judicatories found under the Plan from the Presbyterian Church. In total, three synods in New York and one synod in Ohio along with 28 presbyteries, 509 ministers, and 60 thousand church members (one-fifth of the PCUSA's membership) were excluded from the church. New School leaders reacted by meeting in Auburn, New York, and issuing the Auburn Declaration, a 16-point defense of their Calvinist orthodoxy.

When the General Assembly met in May 1838 at Philadelphia, the New School commissioners attempted to be seated but were forced to leave and convene their own General Assembly elsewhere in the city. The Old School and New School factions had finally split into two separate churches that were about equal in size. Both churches, however, claimed to be the Presbyterian Church in the USA. The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania decided that the Old School body was the legal successor of the undivided PCUSA.

The Old School faction was convinced that the Plan of Union with the Congregational churches had undermined Presbyterian doctrine and order. At the 1837 General Assembly, the Old School majority successfully passed resolutions removing all judicatories found under the Plan from the Presbyterian Church. In total, three synods in New York and one synod in Ohio along with 28 presbyteries, 509 ministers, and 60 thousand church members (one-fifth of the PCUSA's membership) were excluded from the church. New School leaders reacted by meeting in Auburn, New York, and issuing the Auburn Declaration, a 16-point defense of their Calvinist orthodoxy.

When the General Assembly met in May 1838 at Philadelphia, the New School commissioners attempted to be seated but were forced to leave and convene their own General Assembly elsewhere in the city. The Old School and New School factions had finally split into two separate churches that were about equal in size. Both churches, however, claimed to be the Presbyterian Church in the USA. The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania decided that the Old School body was the legal successor of the undivided PCUSA.

Slavery dispute and Civil War division

The Synod of Philadelphia and New York had expressed moderate

The Synod of Philadelphia and New York had expressed moderate abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

sentiments in 1787 when it recommended that all its members "use the most prudent measures consistent with the interests and state of civil society, in the countries where they live, to procure eventually the final abolition of slavery in America". At the same time, Presbyterians in the South were content to reinforce the status quo in their religious teaching, such as in "The Negro Catechism" written by North Carolina Presbyterian minister Henry Pattillo. In Pattillo's catechism

A catechism (; from grc, κατηχέω, "to teach orally") is a summary or exposition of doctrine and serves as a learning introduction to the Sacraments traditionally used in catechesis, or Christian religious teaching of children and adul ...

, slaves were taught that their roles in life had been ordained by God.

In 1795, the General Assembly ruled that slaveholding was not grounds for excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

but also expressed support for the eventual abolition of slavery. Later, the General Assembly called slavery "a gross violation of the most precious and sacred rights of human nature; as utterly inconsistent with the law of God". Nevertheless, in 1818, George Bourne, an abolitionist and Presbyterian minister serving in Virginia, was defrocked by his Southern presbytery in retaliation for his strong criticisms of Christian slaveholders. The General Assembly was increasingly reluctant to address the issue, preferring to take a moderate stance in the debate, but by the 1830s, tensions over slavery were increasing at the same time the church was dividing over the Old School–New School Controversy.

The conflict between Old School and New School factions merged with the slavery controversy. The New School's enthusiasm for moral reform and voluntary societies was evident in its increasing identification with the abolitionist movement. The Old School, however, was convinced that the General Assembly and the larger church should not legislate on moral issues that were not explicitly addressed in the Bible. This effectively drove the majority of Southern Presbyterians to support the Old School faction.

The first definitive split over slavery occurred within the New School Presbyterian Church. In 1858, Southern synods and presbyteries belonging to the New School withdrew and established the pro-slavery United Synod of the Presbyterian Church. Old School Presbyterians followed in 1861 after the start of hostilities in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. In May, the Old School General Assembly passed the controversial Gardiner Spring Resolutions, which called for Presbyterians to support the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

and Federal Government of the United States

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fede ...

.

In response, representatives of Old School presbyteries in the South met in December at Augusta, Georgia, to form the Presbyterian Church in the

In response, representatives of Old School presbyteries in the South met in December at Augusta, Georgia, to form the Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

. The Presbyterian Church in the CSA absorbed the smaller United Synod in 1864. After the Confederacy's defeat in 1865, it was renamed the Presbyterian Church in the United States

The Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS, originally Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America) was a Protestant denomination in the Southern and border states of the United States that existed from 1861 to 1983. That ye ...

(PCUS) and was commonly nicknamed the "Southern Presbyterian Church" throughout its history, while the PCUSA was known as the "Northern Presbyterian Church".

Old School-New School reunion in the North

By the 1850s, New School Presbyterians in the North had moved to more moderate positions and reasserted a stronger Presbyterian identity. This was helped in 1852 when the Plan of Union between the New School Church and the Congregationalists was discontinued. Northern Presbyterians of both the Old and New School participated in the Christian Commission that provided religious and social services to Union soldiers during the Civil War. Furthermore, both schools boldly proclaimed the righteousness of the Union cause and engaged in speculation about the role of a newly restored America in ushering in themillennium

A millennium (plural millennia or millenniums) is a period of one thousand years, sometimes called a kiloannus, kiloannum (ka), or kiloyear (ky). Normally, the word is used specifically for periods of a thousand years that begin at the starting ...

. This was, in effect, the Old School's repudiation of its teaching against involving the church in political affairs.

A majority of Old School leaders in the North were convinced of the orthodoxy of the New School. Some within the Old School, chiefly Princeton theologian Charles Hodge, claimed that there were still ministers within the New School who adhered to New Haven theology. Nevertheless, the Old and New School General Assemblies in the North and a majority of their presbyteries approved the reunion in 1869 of the PCUSA.

Higher criticism and the Briggs heresy trial

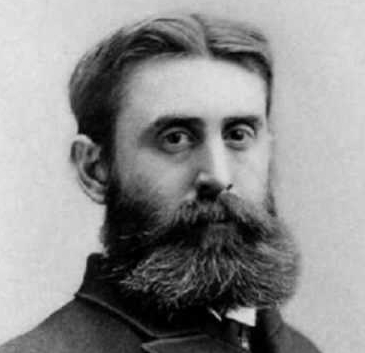

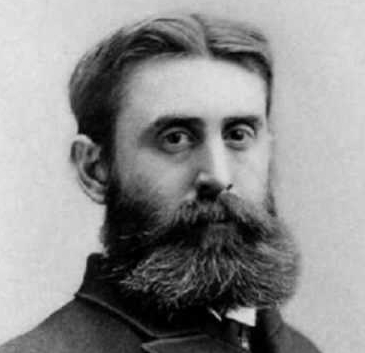

In the decades after the reunion of 1869, conservatives expressed fear over the threat of " broad churchism" and modernist theology. Such fears were prompted in part by heresy trials (such as the 1874 acquittal of popular Chicago preacher

In the decades after the reunion of 1869, conservatives expressed fear over the threat of " broad churchism" and modernist theology. Such fears were prompted in part by heresy trials (such as the 1874 acquittal of popular Chicago preacher David Swing

David Swing (August 23, 1830October 3, 1894) was a United States teacher and clergyman who was the most popular Chicago preacher of his time.

Early life

Swing was born to Alsatian immigrant parents in Cincinnati, Ohio. Citation: Joseph Fort ...

) and a growing movement to revise the Westminster Confession. This liberal movement was opposed by Princeton theologians A. A. Hodge

Archibald Alexander Hodge (July 18, 1823 – November 12, 1886), an American Presbyterian leader, was the principal of Princeton Seminary between 1878 and 1886.

Biography

He was born on July 18, 1823 to Sarah and Charles Hodge in Princet ...

and B. B. Warfield.

While Darwinian evolution never became an issue for northern Presbyterians as most accommodated themselves to some form of theistic evolution

Theistic evolution (also known as theistic evolutionism or God-guided evolution) is a theological view that God creates through laws of nature. Its religious teachings are fully compatible with the findings of modern science, including biologica ...

, the new discipline of biblical interpretation known as higher criticism

Historical criticism, also known as the historical-critical method or higher criticism, is a branch of criticism that investigates the origins of ancient texts in order to understand "the world behind the text". While often discussed in terms of ...

would become highly controversial. Utilizing comparative linguistics, archaeology, and literary analysis, German proponents of high criticism, such as Julius Wellhausen

Julius Wellhausen (17 May 1844 – 7 January 1918) was a German biblical scholar and orientalist. In the course of his career, he moved from Old Testament research through Islamic studies to New Testament scholarship. Wellhausen contributed to t ...

and David Friedrich Strauss, began questioning long-held assumptions about the Bible. At the forefront of the controversy in the PCUSA was Charles A. Briggs, a professor at PCUSA's Union Theological Seminary in New York.

While Briggs held to traditional Christian teaching in many areas, such as his belief in the virgin birth of Jesus, conservatives were alarmed by his assertion that doctrines were historical constructs that had to change over time. He did not believe that the Pentateuch

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

was authored by Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu ( Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pr ...

or that the book of Isaiah

The Book of Isaiah ( he, ספר ישעיהו, ) is the first of the Latter Prophets in the Hebrew Bible and the first of the Major Prophets in the Christian Old Testament. It is identified by a superscription as the words of the 8th-century B ...

had a single author. In addition, he also denied that Biblical prophecy was a precise prediction of the future. In 1891, Briggs preached a sermon in which he claimed the Bible contained errors, a position many in the church considered contrary to the Westminster Confession's doctrines of verbal inspiration and Biblical inerrancy.

In response, 63 presbyteries petitioned the General Assembly to take action against Briggs. The 1891 General Assembly vetoed his appointment to Union Theological Seminary's chair

A chair is a type of seat, typically designed for one person and consisting of one or more legs, a flat or slightly angled seat and a back-rest. They may be made of wood, metal, or synthetic materials, and may be padded or upholstered in vari ...

of Biblical studies

Biblical studies is the academic application of a set of diverse disciplines to the study of the Bible (the Old Testament and New Testament).''Introduction to Biblical Studies, Second Edition'' by Steve Moyise (Oct 27, 2004) pages 11–12 ...

, and two years later Briggs was found guilty of heresy and suspended from the ministry. Ultimately, Union Theological Seminary refused to remove Briggs from his position and severed its ties to the Presbyterian Church.

In 1892, conservatives in the General Assembly were successful in adopting the Portland Deliverance, a statement named for the assembly's meeting place, Portland, Oregon. The Deliverance reasserted the church's belief in biblical inerrancy and required any minister who could not affirm the Bible as "the only infallible rule of faith and practice" to withdraw from the Presbyterian ministry. The Portland Deliverance would be used to convict Briggs of heresy.

20th century

Confessional revision

Briggs' heresy trial was a setback to the movement for confessional revision, which wanted to soften the Westminster Confession's Calvinistic doctrines of predestination and

Briggs' heresy trial was a setback to the movement for confessional revision, which wanted to soften the Westminster Confession's Calvinistic doctrines of predestination and election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operat ...

. Nevertheless, overtures continued to come before the General Assembly. In 1903, two chapters on "The Holy Spirit

In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is the divine force, quality, and influence of God over the Universe or over his creatures. In Nicene Christianity, the Holy Spirit or Holy Ghost is the third person of the Trinity. In Islam, the Holy Spirit acts as ...

" and "The Love of God and Missions" were added to the Confession and a reference to the pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

being the anti-christ was deleted. Most objectionable to conservatives, a new "Declaratory Statement" was added to clarify the church's doctrine of election. Conservatives criticized the "Declaratory Statement" and claimed that it promoted Arminianism.

The 1903 revision of the Westminster Confession eventually led a large number of congregations from the Arminian–leaning Cumberland Presbyterian Church to reunite with the PCUSA in 1906. While overwhelmingly approved, the reunion caused controversy within the PCUSA due to concerns over doctrinal compatibility and racial segregation in the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. Warfield was a strong critic of the merger on doctrinal grounds. Northern Presbyterians, such as Francis James Grimké and Herrick Johnson, objected to the creation of racially segregated presbyteries in the South, a concession demanded by the Cumberland Presbyterians as the price for reunion. Despite these objections, the merger was overwhelmingly approved.

Social gospel and evangelization

By the early 20th century, theSocial Gospel

The Social Gospel is a social movement within Protestantism that aims to apply Christian ethics to social problems, especially issues of social justice such as economic inequality, poverty, alcoholism, crime, racial tensions, slums, unclean envir ...

movement, which stressed social as well as individual salvation, had found support within the Presbyterian Church. Important figures such as Henry Sloane Coffin, president of New York's Union Seminary and a leading liberal, backed the movement. The most important promoter of the Social Gospel among Presbyterians was Charles Stelzle, the first head of the Workingmen's Department of the PCUSA. The department, created in 1903 to minister to working class immigrants, was the first official denominational agency to pursue a Social Gospel agenda. According to church historian Bradley Longfield, Stelzle "advocated for child-labor laws, workers' compensation, adequate housing, and more effective ways to address vice and crime in order to advance the kingdom of God." After a reorganization in 1908, the work of the department was split between the newly created Department of Church and Labor and the Department of Immigration.

While the Social Gospel was making inroads within the denomination, the ministry of baseball player turned evangelist Billy Sunday demonstrated that evangelization

In Christianity, evangelism (or witnessing) is the act of preaching the gospel with the intention of sharing the message and teachings of Jesus Christ.

Christians who specialize in evangelism are often known as evangelists, whether they are ...

and the revivalist tradition was still a force within the denomination. Sunday became the most prominent evangelist of the early 20th century, preaching to over 100 million people and leading an estimated million to conversion throughout his career. Whereas Stelzle emphasized the social aspects of Christianity, Sunday's focus was primarily on the conversion and moral responsibility of the individual.

Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy

Between 1922 and 1936, the PCUSA became embroiled in the so-called Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy. Tensions had been building in the years following the Old School-New School reunion of 1869 and the Briggs heresy trial of 1893. In 1909, the conflict was further exacerbated when the Presbytery of New York granted licenses to preach to a group of men who could not affirm the virgin birth of Jesus. The presbytery's action was appealed to the 1910 General Assembly, which then required all ministry candidates to affirm five essential or fundamental tenets of the Christian faith: biblical inerrancy, the virgin birth,

Between 1922 and 1936, the PCUSA became embroiled in the so-called Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy. Tensions had been building in the years following the Old School-New School reunion of 1869 and the Briggs heresy trial of 1893. In 1909, the conflict was further exacerbated when the Presbytery of New York granted licenses to preach to a group of men who could not affirm the virgin birth of Jesus. The presbytery's action was appealed to the 1910 General Assembly, which then required all ministry candidates to affirm five essential or fundamental tenets of the Christian faith: biblical inerrancy, the virgin birth, substitutionary atonement

Substitutionary atonement, also called vicarious atonement, is a central concept within Christian theology which asserts that Jesus died "for us", as propagated by the Western classic and objective paradigms of atonement in Christianity, which ...

, the bodily resurrection, and the miracles of Christ

The miracles of Jesus are miraculous deeds attributed to Jesus in Christian and Islamic texts. The majority are faith healings, exorcisms, resurrections, and control over nature.

In the Synoptic Gospels (Mark, Matthew, and Luke), Jesus refuse ...

.

These themes were later expounded upon in '' The Fundamentals'', a series of essays financed by wealthy Presbyterians Milton and Lyman Stewart

Lyman Stewart (July 22, 1840 – September 28, 1923) was a U.S. businessman and co-founder of Union Oil Company of California, which eventually became Unocal. Stewart was also a significant Christian philanthropist and cofounder of the Bible Insti ...

. While the authors were drawn from the wider evangelical community, a large proportion were Presbyterian, including Warfield, William Erdman, Charles Erdman, and Robert Elliott Speer

Robert Elliott Speer (10 September 1867 – 23 November 1947) was an American Presbyterian religious leader and an authority on missions.

Biography

He was born at Huntingdon, Pennsylvania on 10 September 1867. He graduated from Phillips Academy ...

.

In 1922, prominent New York minister Harry Emerson Fosdick (who was Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul c ...

but serving as pastor of New York's First Presbyterian Church by special arrangement) preached a sermon entitled "Shall the Fundamentalists Win?", challenging what he perceived to be a rising tide of intolerance against modernist or liberal theology

Religious liberalism is a conception of religion (or of a particular religion) which emphasizes personal and group liberty and rationality. It is an attitude towards one's own religion (as opposed to criticism of religion from a secular position ...

within the denomination. In response, conservative Presbyterian minister Clarence E. Macartney

Clarence Edward Noble McCartney (September 18, 1879 – February 19, 1957) was a prominent conservative Presbyterian pastor and author. With J. Gresham Machen, he was one of the main leaders of the conservatives during the Fundamentalist� ...

preached a sermon called "Shall Unbelief Win?", in which he warned that liberalism would lead to "a Christianity without worship, without God, and without Jesus Christ". J. Gresham Machen

John Gresham Machen (; 1881–1937) was an American Presbyterian New Testament scholar and educator in the early 20th century. He was the Professor of New Testament at Princeton Seminary between 1906 and 1929, and led a revolt against modernist ...

of Princeton Theological Seminary also responded to Fosdick with his 1923 book ''Christianity and Liberalism'', arguing that liberalism and Christianity were two different religions.

The 1923 General Assembly reaffirmed the five fundamentals and ordered the Presbytery of New York to ensure that First Presbyterian Church conformed to the Westminster Confession. A month later, the presbytery licensed two ministers who could not affirm the virgin birth, and in February 1924, it acquitted Fosdick who subsequently left his post in the Presbyterian Church.

That same year, a group of liberal ministers composed a statement defending their theological views known as the Auburn Affirmation due to the fact that it was based on the work of Robert Hastings Nichols of Auburn Seminary. Citing the Adopting Act of 1729, the Affirmation claimed for the PCUSA a heritage of doctrinal liberty. It also argued that church doctrine could only be established by action of the General Assembly and a majority of presbyteries; therefore, according to the Affirmation, the General Assembly acted unconstitutionally when it required adherence to the five fundamentals.

The 1925 General Assembly faced the threat of schism over the actions of the Presbytery of New York. Attempting to deescalate the situation, General Assembly moderator Charles Erdman proposed the creation of a special commission to study the church's problems and find solutions. The commission's report, released in 1926, sought to find a moderate approach to solving the church's theological conflict. In agreement with the Auburn Affirmation, the commission concluded that doctrinal pronouncements issued by the General Assembly were not binding without the approval of a majority of the presbyteries. In a defeat for conservatives, the report was adopted by the General Assembly. Conservatives were further disenchanted in 1929 when the General Assembly approved the ordination of women as lay elders.

In 1929, Princeton Theological Seminary was reorganized to make the school's leadership and faculty more representative of the wider church rather than just Old School Presbyterianism. Two of the seminary's new board members were signatories to the Auburn Affirmation. In order to preserve Princeton's Old School legacy, Machen and several of his colleagues founded Westminster Theological Seminary.

Further controversy would erupt over the state of the church's missionary efforts. Sensing a loss of interest and support for foreign missions, the nondenominational Laymen's Foreign Mission Inquiry published '' Re-Thinking Missions: A Laymen's Inquiry after One Hundred Years'' in 1932, which promoted universalism and rejected the uniqueness of Christianity. Because the Inquiry had been initially supported by the PCUSA, many conservatives were concerned that ''Re-Thinking Missions'' represented the views of PCUSA's Board of Foreign Missions. Even after board members affirmed their belief in "Jesus Christ as the only Lord and Saviour", some conservatives remained skeptical, and such fears were reinforced by modernist missionaries, including celebrated author Pearl S. Buck. While initially evangelical, Buck's religious views developed over time to deny the divinity of Christ.

In 1933, Machen and other conservatives founded the

In 1929, Princeton Theological Seminary was reorganized to make the school's leadership and faculty more representative of the wider church rather than just Old School Presbyterianism. Two of the seminary's new board members were signatories to the Auburn Affirmation. In order to preserve Princeton's Old School legacy, Machen and several of his colleagues founded Westminster Theological Seminary.

Further controversy would erupt over the state of the church's missionary efforts. Sensing a loss of interest and support for foreign missions, the nondenominational Laymen's Foreign Mission Inquiry published '' Re-Thinking Missions: A Laymen's Inquiry after One Hundred Years'' in 1932, which promoted universalism and rejected the uniqueness of Christianity. Because the Inquiry had been initially supported by the PCUSA, many conservatives were concerned that ''Re-Thinking Missions'' represented the views of PCUSA's Board of Foreign Missions. Even after board members affirmed their belief in "Jesus Christ as the only Lord and Saviour", some conservatives remained skeptical, and such fears were reinforced by modernist missionaries, including celebrated author Pearl S. Buck. While initially evangelical, Buck's religious views developed over time to deny the divinity of Christ.

In 1933, Machen and other conservatives founded the Independent Board for Presbyterian Foreign Missions The Independent Board for Presbyterian Foreign Missions (IBPFM) is a small Presbyterian mission organization, which early in its history became an approved agency of the Bible Presbyterian Church. Founded in 1933 by J. Gresham Machen, the IBPFM pla ...

. A year later, the General Assembly declared the Independent Board unconstitutional and demanded that all church members cut ties with it. Machen refused to obey, and his ordination was suspended in 1936. Afterwards, Machen led an exodus of conservatives to form what would be later known as the Orthodox Presbyterian Church

The Orthodox Presbyterian Church (OPC) is a confessional Presbyterian denomination located primarily in the United States, with additional congregations in Canada, Bermuda, and Puerto Rico. It was founded by conservative members of the Presbyter ...

.

Later history

With the onset of theGreat Depression