Powel Crosley Jr on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Powel Crosley Jr. (September 18, 1886 – March 28, 1961) was an American

In 1921 Crosley's young son asked for a

In 1921 Crosley's young son asked for a  In 1928 Crosley's firm arranged for the construction of the Crosley Building at Camp Washington, a Cincinnati neighborhood, and used the facility for its for radio manufacturing, radio broadcasting, and for manufacturing other devices.

In 1930 Crosley was marketing the "Roamio," with "screen grid neutrodyne power speaker" for automotive use. Priced at $75, before accessories and installation, it was claimed to be able to receive thirty stations with no signal strength change.

In 1928 Crosley's firm arranged for the construction of the Crosley Building at Camp Washington, a Cincinnati neighborhood, and used the facility for its for radio manufacturing, radio broadcasting, and for manufacturing other devices.

In 1930 Crosley was marketing the "Roamio," with "screen grid neutrodyne power speaker" for automotive use. Priced at $75, before accessories and installation, it was claimed to be able to receive thirty stations with no signal strength change.

In the 1930s Crosley added refrigerators and other household appliances and consumer goods to his company's product line.

Crosley's "

In the 1930s Crosley added refrigerators and other household appliances and consumer goods to his company's product line.

Crosley's "

The Crosley "Moonbeam" was built in

The Crosley "Moonbeam" was built in  In 1933 Frenchman Henri Mignet designed the HM.14 "Pou du Ciel" ("Flying Flea"). He envisioned a simple aircraft that amateurs could build, and even teach themselves to fly. In an attempt to render the aircraft stall proof and safe for amateur pilots to fly, Mignet staggered the two main wings. The Mignet-Crosley "Pou du Ciel" is the first HM.14 made and flown in the United States. Edward Nirmaier, a Crosley employee, and two other men built the airplane in November 1935 for Crosley, who believed that the affordable "Flea" could become a popular aircraft in the United States. After several flights, a crash at the Miami Air Races in December 1935 finally grounded the Crosley HM.14. Although the airplane enjoyed a period of intense popularity in France and England, a series of accidents in 1935-36 permanently ruined the airplane's reputation.

In 1933 Frenchman Henri Mignet designed the HM.14 "Pou du Ciel" ("Flying Flea"). He envisioned a simple aircraft that amateurs could build, and even teach themselves to fly. In an attempt to render the aircraft stall proof and safe for amateur pilots to fly, Mignet staggered the two main wings. The Mignet-Crosley "Pou du Ciel" is the first HM.14 made and flown in the United States. Edward Nirmaier, a Crosley employee, and two other men built the airplane in November 1935 for Crosley, who believed that the affordable "Flea" could become a popular aircraft in the United States. After several flights, a crash at the Miami Air Races in December 1935 finally grounded the Crosley HM.14. Although the airplane enjoyed a period of intense popularity in France and England, a series of accidents in 1935-36 permanently ruined the airplane's reputation.

Of all Crosley's dreams, success at building an affordable automobile for Americans was possibly the only major one eventually to elude him. In the years leading up to

Of all Crosley's dreams, success at building an affordable automobile for Americans was possibly the only major one eventually to elude him. In the years leading up to

Crosley's company was involved in war production planning before December 1941, and like the rest of American industry, it focused on manufacturing war-related products during World War II. The company made a variety of products, including

Crosley's company was involved in war production planning before December 1941, and like the rest of American industry, it focused on manufacturing war-related products during World War II. The company made a variety of products, including

Crosley Automobile Club Inc.

The Crosley Car Owners Club (CCOC)

North Vernon, Indiana

Crosley Radio

i

''West Coast Midnight Run''

2013 edition *

"Crosleys had the Right Formula"

''Cincinnati Enquirer''

Pinecroft

Cincinnati, Ohio

The Powel Crosley Estate

(Seagate),

inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an ...

, industrialist

A business magnate, also known as a tycoon, is a person who has achieved immense wealth through the ownership of multiple lines of enterprise. The term characteristically refers to a powerful entrepreneur or investor who controls, through perso ...

, and entrepreneur

Entrepreneurship is the creation or extraction of economic value. With this definition, entrepreneurship is viewed as change, generally entailing risk beyond what is normally encountered in starting a business, which may include other values th ...

. He was also a pioneer in radio

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmit ...

broadcasting

Broadcasting is the distribution (business), distribution of sound, audio or video content to a dispersed audience via any electronic medium (communication), mass communications medium, but typically one using the electromagnetic spectrum (radio ...

, and owner of the Cincinnati Reds

The Cincinnati Reds are an American professional baseball team based in Cincinnati. They compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (NL) National League Central, Central division and were a charter member of ...

major league baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding tea ...

team. In addition, Crosley's companies manufactured Crosley

Crosley was a small, independent American manufacturer of subcompact cars, bordering on microcars. At first called the Crosley Corporation and later Crosley Motors Incorporated, the Cincinnati, Ohio, firm was active from 1939 to 1952, inter ...

automobile

A car or automobile is a motor vehicle with Wheel, wheels. Most definitions of ''cars'' say that they run primarily on roads, Car seat, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport private transport#Personal transport, pe ...

s and radios, and operated WLW

WLW (700 AM) is a commercial news/talk radio station licensed to Cincinnati, Ohio. Owned by iHeartMedia, WLW is a clear-channel station, often identifying itself as The Big One.

WLW operates with around the clock. Its daytime signal provides ...

radio station. Crosley, once dubbed "The Henry Ford of Radio," was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame

The Automotive Hall of Fame is an American museum. It was founded in 1939 and has over 800 worldwide honorees. It is part of the MotorCities National Heritage Area. the Automotive Hall of Fame includes persons who have contributed greatly to au ...

in 2010 and the National Radio Hall of Fame

The Radio Hall of Fame, formerly the National Radio Hall of Fame, is an American organization created by the Emerson Radio Corporation in 1988.

Three years later, Bruce DuMont, founder, president, and CEO of the Museum of Broadcast Communicatio ...

in 2013.

He and his brother, Lewis M. Crosley

Lewis M. Crosley (November 24, 1888 – November 6, 1978) of Cincinnati, Ohio was an American industrialist and businessman. He was the brother of Powel Crosley Jr. Lewis Crosley is credited with being his more famous brother's business partner ...

, were responsible for many firsts in consumer products and broadcasting. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Crosley's facilities produced more proximity fuze

A proximity fuze (or fuse) is a Fuze (munitions), fuze that detonates an Explosive material, explosive device automatically when the distance to the target becomes smaller than a predetermined value. Proximity fuzes are designed for targets such ...

s than any other U.S. manufacturer, and made several production design innovations. Crosley Field

Crosley Field was a Major League Baseball park in Cincinnati, Ohio. It was the home field of the National League's Cincinnati Reds from 1912 through June 24, 1970, and the original Cincinnati Bengals football team, members of the second (1937) an ...

, a stadium in Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, was renamed for him, and the street-level main entrance to Great American Ball Park

Great American Ball Park is a baseball stadium in Cincinnati, Ohio. It served as the home stadium of the Cincinnati Reds of Major League Baseball (MLB), and opened on March 31, 2003, replacing Cinergy Field (formerly Riverfront Stadium), the R ...

in Cincinnati is named Crosley Terrace in his honor. Crosley's Pinecroft estate home in Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, and Seagate, his former winter retreat in Sarasota, Florida

Sarasota () is a city in Sarasota County on the Gulf Coast of the U.S. state of Florida. The area is renowned for its cultural and environmental amenities, beaches, resorts, and the Sarasota School of Architecture. The city is located in the sout ...

are listed in the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

.

Early life and education

Powel Crosley Jr. was born on September 18, 1886, inCincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

, to Charlotte Wooley (Utz) (1864–1949) and Powel Crosley Sr. (1849–1932), a lawyer. Powel Jr. was the oldest of the family's four children. Crosley became interested in the mechanics of automobile

A car or automobile is a motor vehicle with Wheel, wheels. Most definitions of ''cars'' say that they run primarily on roads, Car seat, seat one to eight people, have four wheels, and mainly transport private transport#Personal transport, pe ...

s at a young age and wanted to become an automaker. While living with his family in College Hill, a suburb of Cincinnati, twelve-year-old Crosley made his first attempt at building a vehicle.

Crosley began high school in College Hill and transferred to the Ohio Military Institute

The Ohio Military Institute was a higher education institution located in Cincinnati, Ohio. Founded in 1890, it closed in 1958.

History

The Ohio Military Institute was established in 1890, on the foundation then known as Belmont College, and in ...

. In 1904 Crosley enrolled at the University of Cincinnati

The University of Cincinnati (UC or Cincinnati) is a public research university in Cincinnati, Ohio. Founded in 1819 as Cincinnati College, it is the oldest institution of higher education in Cincinnati and has an annual enrollment of over 44,00 ...

, where he began studies in engineering, but switched to law, primarily to satisfy his father, before dropping out of college in 1906 after two years of study.

Marriage and family

Crosley married Gwendolyn Bakewell Aiken (1889–1939) in Hamilton County, Ohio, on October 17, 1910. They had two children. After his marriage, Crosley continued to work in automobile sales in Muncie to earn money to buy a house, while his wife returned to Cincinnati to live with her parents. The young couple saw each other on the weekends until Crosley returned to Cincinnati in 1911 to live and work after the birth of his first child. Gwendolyn Crosley, who suffered fromtuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

, died at the Crosleys' winter home in Sarasota, Florida

Sarasota () is a city in Sarasota County on the Gulf Coast of the U.S. state of Florida. The area is renowned for its cultural and environmental amenities, beaches, resorts, and the Sarasota School of Architecture. The city is located in the sout ...

, on February 26, 1939.

Crosley married Eva Emily Brokaw (1912–1955) in 1952. She died in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Real estate

Crosley's primary residence was Pinecroft, an estate home built in 1929 in the Mount Airy section of Cincinnati, Ohio. He also had Seagate, a winter retreat inManatee County, Florida

Manatee County is a county in the Central Florida portion of the U.S. state of Florida. As of the 2020 US Census, the population was 399,710. Manatee County is part of the North Port-Sarasota-Bradenton Metropolitan Statistical Area. Its county ...

, built for his first wife, Gwendolyn. In addition, Crosley owned several vacation properties.

Pinecroft

Pinecroft, Crosley's two-story, ,Tudor Revival

Tudor Revival architecture (also known as mock Tudor in the UK) first manifested itself in domestic architecture in the United Kingdom in the latter half of the 19th century. Based on revival of aspects that were perceived as Tudor architecture ...

-style mansion and other buildings on his estate in Mount Airy was designed by New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

-based architect Dwight James Baum

Dwight James Baum (June 24, 1886 – December 14, 1939) was an American architect most active in New York and in Sarasota, Florida. His work includes Cà d'Zan, the Sarasota Times Building (1925), Sarasota County Courthouse (1926), early reside ...

and built in 1928–29. Crosley's daughter, Marth Page (Crosley) Kess, sold the property after her father's death in 1961, and the Franciscan Sisters of the Poor The Franciscan Sisters of the Poor ( la, Sorores Franciscanae Pauperorum, abbreviated to S.F.P.) are a religious congregation which was established in 1959 as an independent branch from the Congregation of the Poor Sisters of St. Francis, founded i ...

acquired the property in 1963. Saint Francis Hospital bought a portion of the property north of the Crosley mansion in 1971 and built a hospital, which was renamed Mercy Hospitals West in 2001. The land surrounding the home has been subdivided into parcels, but the Franciscan Sisters have used the mansion as a retreat since the early 1970s. Pinecroft was added to the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

in 2008. See also:

Seagate

Seagate, also known as the Bay Club, alongSarasota Bay

Sarasota Bay is a lagoon located off the central west coast of Florida in the United States. Though no significant single stream of freshwater enters the bay, with a drainage basin limited to 150 square miles in Manatee and Sarasota Counties, it ...

in the southwest corner of Manatee County, Florida

Manatee County is a county in the Central Florida portion of the U.S. state of Florida. As of the 2020 US Census, the population was 399,710. Manatee County is part of the North Port-Sarasota-Bradenton Metropolitan Statistical Area. Its county ...

, was a Mediterranean Revival-style home designed for Crosley by New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

and Sarasota

Sarasota () is a city in Sarasota County on the Gulf Coast of the U.S. state of Florida. The area is renowned for its cultural and environmental amenities, beaches, resorts, and the Sarasota School of Architecture. The city is located in the sout ...

architect George Albree Freeman Jr.

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presiden ...

, with Ivo A. de Minicis, a Tampa, Florida

Tampa () is a city on the Gulf Coast of the United States, Gulf Coast of the U.S. state of Florida. The city's borders include the north shore of Tampa Bay and the east shore of Old Tampa Bay. Tampa is the largest city in the Tampa Bay area and ...

, architect, drafting the plans. Sarasota contractor Paul W. Bergman built the winter retreat in 1929–30 on a parcel of land. The two-and-a-half-story house include ten bedrooms and ten bathrooms, as well as auxiliary garages and living quarters for staff. The house contains and is reportedly the first residence built in Florida using steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ty ...

-frame construction to provide protection against fires and hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depend ...

s. After Crosley's wife, Gwendolyn, died of tuberculosis at the retreat in 1939, he rarely used the house. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Crosley allowed the U.S. Army Air Corps

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. After World War I, as early aviation became an increasingly important part of modern warfare, a philosophical ri ...

to use the retreat for its airmen training at the nearby Sarasota Army Air Base. Crosley sold his estate property in 1947 to the D and D Corporation.

Mabel and Freeman Horton purchased the property in 1948 and owned Seagate for nearly forty years. The house and was added to the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

on January 21, 1983, by a subsequent owner who intended to build an exclusive condominium

A condominium (or condo for short) is an ownership structure whereby a building is divided into several units that are each separately owned, surrounded by common areas that are jointly owned. The term can be applied to the building or complex ...

project on the site using the historic house as a clubhouse, but the project failed when the economy faltered shortly thereafter. Kafi Benz

Kafi Benz (born 1941) is an American author and artist who began participation in social entrepreneurship through environmental preservation and regional planning in 1959 as a member of the ''Jersey Jetport Site Association'', which opposed plans ...

, the Friends of Seagate Inc., a nonprofit corporation, and local residents saved Seagate from commercial development, and initiated a campaign for its preservation and public acquisition. In 1991 the state of Florida purchased the property and of the bay-front estate that included the structures that Crosley had built in 1929–30. A larger portion of the original property was developed into a satellite campus for the University of South Florida

The University of South Florida (USF) is a public research university with its main campus located in Tampa, Florida, and other campuses in St. Petersburg and Sarasota. It is one of 12 members of the State University System of Florida. USF is ...

. The University of South Florida Sarasota-Manatee

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, th ...

campus opened its new facilities in August 2006. The present-day mansion, called the Powel Crosley Estate, is used as a meeting, conference, and event venue.

Vacation homes

Crosley, an avid sportsman, also owned several sports, hunting, and fishing camps, including an island retreat called Nikassi onMcGregor Bay

Rainbow Country is a local services board in the Canadian province of Ontario. It encompasses and provides services to the communities of Whitefish Falls and Willisville in the Unorganized North Sudbury District and Birch Island and McGregor Bay ...

, Lake Huron

Lake Huron ( ) is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. Hydrology, Hydrologically, it comprises the easterly portion of Lake Michigan–Huron, having the same surface elevation as Lake Michigan, to which it is connected by the , Strait ...

, Canada; Bull Island, South Carolina; Pimlico Plantation, along the Cooper River north of Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

; Sleepy Hollow Farm, a retreat in Jennings County, Indiana

Jennings County is a county located in the U.S. state of Indiana. As of 2020, the population was 27,613. The county seat is Vernon.

History

Jennings County was formed in 1817. It was named for the first Governor of Indiana and a nine-term con ...

and a house at Cat Cays, Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

.

Early career

Crosley began work selling bonds for aninvestment banker

Investment banking pertains to certain activities of a financial services company or a corporate division that consist in advisory-based financial transactions on behalf of individuals, corporations, and governments. Traditionally associated with ...

; however, at the age of twenty-one he decided to pursue a career in automobile manufacturing. The mass-production

Mass production, also known as flow production or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines. Together with job production and bat ...

techniques employed by Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that mi ...

also caught his attention and would be implemented by his brother, Lewis, when the two began manufacturing radios in 1921.

In 1907 Crosley formed a company to build the Marathon Six, a six-cylinder

The straight-six engine (also referred to as an inline-six engine; abbreviated I6 or L6) is a piston engine with six cylinders arranged in a straight line along the crankshaft. A straight-six engine has perfect primary and secondary engine balan ...

model priced at $1,700, which was at the low end of the luxury car market. With $10,000 in capital that he raised from investors, Crosley established Marathon Six Automotive inexpensive automobile, in Connersville, Indiana

Connersville is a city in Fayette County, east central Indiana, United States, east by southeast of Indianapolis. The population was 13,481 at the 2010 census. The city is the county seat of and the largest and only incorporated town in F ...

, and built a prototype

A prototype is an early sample, model, or release of a product built to test a concept or process. It is a term used in a variety of contexts, including semantics, design, electronics, and Software prototyping, software programming. A prototyp ...

of his car, but a nationwide financial panic caused investment capital to dwindle and he failed to fund its production.Banks, "Big Dream, Small Car," pp. 29–30.

Still determined to establish himself as an automaker, Crosley moved to Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

, Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

, where he worked for Carl G. Fisher

Carl Graham Fisher (January 12, 1874 – July 15, 1939) was an American entrepreneur. He was an important figure in the automotive industry, in highway construction, and in real estate development.

In his early life in Indiana, despite fa ...

as a shop hand at the Fisher Automobile Company. Crosley stayed for about a year, but left after he broke his arm starting a car at the auto dealership. After recovering from his injury at home in College Hill, Crosley returned to Indianapolis in 1909 to briefly work for several auto manufacturers, including jobs as an assistant sales manager for the Parry Auto Company

The Parry (1910) and New Parry (1911–1912) were both Brass Era cars built in Indianapolis, Indiana by the Parry Auto Company. During that time, they produced 3500 vehicles. Two cars are known to exist. A Model 40 from 1910 and a Model 41 fro ...

and a salesman for the National Motor Vehicle Company

The National Motor Vehicle Company was an American manufacturer of automobiles in Indianapolis, Indiana, between 1900 and 1924. One of its presidents, Arthur C. Newby, was also one of the investors who created the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

...

. He also volunteered to help promote National's auto racing team. His next job was selling advertising for ''Motor Vehicle'', an automotive trade journal, but left in 1910 to move to Muncie, Indiana

Muncie ( ) is an incorporated city and the county seat, seat of Delaware County, Indiana, Delaware County, Indiana. Previously known as Buckongahelas Town, named after the legendary Delaware Chief.http://www.delawarecountyhistory.org/history/docs ...

, where he worked in sales for the Inter-State Automobile Company and promoted its racing team.Banks, "Big Dream, Small Car," pp. 30–31.

Early automobile and parts manufacturer

After returning to Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1911, Crosley sold and wrote advertisements for local businesses, but continued to pursue his interests in the automobile industry. He failed in early efforts to manufacture cars for the Hermes Automobile Company and cyclecars for the De Cross Cyclecar Company and the L. Porter Smith and Brothers Company before finding financial success in manufacturing and distributing automobile accessories.Banks, "Big Dream, Small Car," p. 31. In 1916 he co-founded the American Automobile Accessory Company with Ira J. Cooper. The company's bestseller was a tire liner of Crosley's invention. Another popular product was a flag holder that held five American flags and clamped to auto radiator caps. By 1919 Crosley had sales of more than $1 million in parts. He also diversified into other consumer products such asphonograph

A phonograph, in its later forms also called a gramophone (as a trademark since 1887, as a generic name in the UK since 1910) or since the 1940s called a record player, or more recently a turntable, is a device for the mechanical and analogu ...

cabinets, radios, and home appliances. Crosley's greatest strength was his ability to invent new products, while his brother, Lewis M. Crosley

Lewis M. Crosley (November 24, 1888 – November 6, 1978) of Cincinnati, Ohio was an American industrialist and businessman. He was the brother of Powel Crosley Jr. Lewis Crosley is credited with being his more famous brother's business partner ...

, excelled in business. Lewis also became head of Crosley's manufacturing operations.

In 1920, Crosley first selected independent local dealers as the best way to take his products to market. He insisted that all sellers of his products must give the consumer the best in parts, service, and satisfaction. Always sensitive to consumers, his products were often less expensive than other name brands, but were guaranteed. Crosley's "money back guarantee

A money-back guarantee, also known as a satisfaction guarantee, is essentially a simple guarantee that, if a buyer is not satisfied with a product or service, a refund will be made.

The 18th century entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood pioneered many of ...

" set a precedent for some of today's most outstanding sales policies.

Radio manufacturer

In 1921 Crosley's young son asked for a

In 1921 Crosley's young son asked for a radio

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmit ...

, a new item at that time, but Crosley was surprised that toy radios cost more than $100 at a local department store. With the help of a booklet called "The ABC of Radio," he and his son decided to assemble the components and build their own crystal radio

A crystal radio receiver, also called a crystal set, is a simple radio receiver, popular in the early days of radio. It uses only the power of the received radio signal to produce sound, needing no external power. It is named for its most impo ...

set. Crosley immediately recognized the appeal of an inexpensive radio and hired two University of Cincinnati students to help design a low-cost set that could be mass-produced. Crosley named the radio the "Harko" and introduced it to the market in 1921. The inexpensive radio set sold for $7, making it affordable to the masses. Soon, the Crosley Radio Corporation was manufacturing radio components for the rapidly growing industry and making its own line of radios.Banks, "Big Dream, Small Car," p. 32.

By 1924 Crosley had moved his company to a larger plant and later made subsequent expansions. The Crosley Radio Corporation

Powel Crosley Jr. (September 18, 1886 – March 28, 1961) was an American inventor, industrialist, and entrepreneur. He was also a pioneer in radio broadcasting, and owner of the Cincinnati Reds major league baseball team. In addition, Crosley ...

became the largest radio manufacturer in the world in 1925; its slogan, "You’re There With A Crosley," was used in all its advertising.

In 1925 Crosley introduced another low-cost radio set. The small, one-tube, regenerative radio was called the "Crosley Pup

Powel Crosley Jr. (September 18, 1886 – March 28, 1961) was an American inventor, industrialist, and entrepreneur. He was also a pioneer in radio broadcasting, and owner of the Cincinnati Reds major league baseball team. In addition, Crosley' ...

" and sold for $9.75. While Victor

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

had Nipper

Nipper (1884 – September 1895) was a dog from Bristol, England, who served as the model for an 1898 painting by Francis Barraud titled ''His Master's Voice''. This image became one of the world's best known trademarks, the famous dog-and- gra ...

, its famous trademark showing a dog listening to "his master's voice

His Master's Voice (HMV) was the name of a major British record label created in 1901 by The Gramophone Co. Ltd. The phrase was coined in the late 1890s from the title of a painting by English artist Francis Barraud, which depicted a Jack Russ ...

" from a phonograph

A phonograph, in its later forms also called a gramophone (as a trademark since 1887, as a generic name in the UK since 1910) or since the 1940s called a record player, or more recently a turntable, is a device for the mechanical and analogu ...

, Crosley adopted a mascot in the form of a dog with headphone

Headphones are a pair of small loudspeaker drivers worn on or around the head over a user's ears. They are electroacoustic transducers, which convert an electrical signal to a corresponding sound. Headphones let a single user listen to an au ...

s listening to a Crosley Pup radioA cute, pudgy little dog named Bonzo, the creation of British artist George E. Studdy, became the inspiration for a variety of commercial merchandise, such as toys, ashtray

An ashtray is a receptacle for ash from cigarettes and cigars. Ashtrays are typically made of fire-retardant material such as glass, heat-resistant plastic, pottery, metal, or stone. It differs from a cigarette receptacle, which is used specifi ...

s, pincushion

A pincushion (or pin cushion) is a small, stuffed cushion, typically across, which is used in sewing to store pins or needles with their heads protruding to take hold of them easily, collect them, and keep them organized.

Pincushions are typ ...

s, trinket boxes, car mascot

A hood ornament (or bonnet ornament in Commonwealth English), also called, motor mascot, or car mascot is a specially crafted model which symbolizes a car company like a badge, located on the front center portion of the hood. It has been used ...

s, jigsaw puzzle

A jigsaw puzzle is a tiling puzzle that requires the assembly of often irregularly shaped interlocking and mosaiced pieces, each of which typically has a portion of a picture. When assembled, the puzzle pieces produce a complete picture.

In th ...

s, books, calendar

A calendar is a system of organizing days. This is done by giving names to periods of time, typically days, weeks, months and years. A date is the designation of a single and specific day within such a system. A calendar is also a physi ...

s, candies, and postcard

A postcard or post card is a piece of thick paper or thin cardboard, typically rectangular, intended for writing and mailing without an envelope. Non-rectangular shapes may also be used but are rare. There are novelty exceptions, such as wood ...

s. The headphone-wearing Bonzo was also associated with the Crosley Pup radios. See

In 1928 Crosley's firm arranged for the construction of the Crosley Building at Camp Washington, a Cincinnati neighborhood, and used the facility for its for radio manufacturing, radio broadcasting, and for manufacturing other devices.

In 1930 Crosley was marketing the "Roamio," with "screen grid neutrodyne power speaker" for automotive use. Priced at $75, before accessories and installation, it was claimed to be able to receive thirty stations with no signal strength change.

In 1928 Crosley's firm arranged for the construction of the Crosley Building at Camp Washington, a Cincinnati neighborhood, and used the facility for its for radio manufacturing, radio broadcasting, and for manufacturing other devices.

In 1930 Crosley was marketing the "Roamio," with "screen grid neutrodyne power speaker" for automotive use. Priced at $75, before accessories and installation, it was claimed to be able to receive thirty stations with no signal strength change.

Radio broadcasting

Once Crosley established himself as a radio manufacturer, he decided to expand into broadcasting as a way to encourage consumers to purchase more radios. In 1921, soon after he built his first radios, Crosley began experimental broadcasts from his home with a 20-watt transmitter using the call sign 8CR. On March 22, 1922, theCrosley Broadcasting Corporation

The Crosley Broadcasting Corporation was a radio and television broadcaster founded by radio manufacturing pioneer Powel Crosley, Jr. It had a major influence in the early years of radio and television broadcasting, and helped the Voice of Amer ...

received a commercial license to operate as WLW

WLW (700 AM) is a commercial news/talk radio station licensed to Cincinnati, Ohio. Owned by iHeartMedia, WLW is a clear-channel station, often identifying itself as The Big One.

WLW operates with around the clock. Its daytime signal provides ...

at 50 watts. Dorman D. Israel, a young radio engineer from the University of Cincinnati, designed and built the station's first two radio transmitters (at 100 and 1,000 watts). The Crosley Corporation claimed that in 1928 WLW became the first 50-kilowatt

The watt (symbol: W) is the unit of power or radiant flux in the International System of Units (SI), equal to 1 joule per second or 1 kg⋅m2⋅s−3. It is used to quantify the rate of energy transfer. The watt is named after James Wa ...

commercial station in the United States with a regular broadcasting schedule. In 1934 Crosley put a 500-kilowatt transmitter on the air, making WLW the station with the world's most powerful radio transmitter for the next five years. (On occasion, the station's power was boosted as high as 700,000 watts.)

Throughout the 1930s, Cincinnati's WLW was considered "the Nation's Station," producing many hours of network programming each week. Among the entertainers who performed live from WLW's studios were Red Skelton

Richard Red Skelton (July 18, 1913September 17, 1997) was an American entertainer best known for his national radio and television shows between 1937 and 1971, especially as host of the television program ''The Red Skelton Show''. He has stars ...

, Doris Day

Doris Day (born Doris Mary Kappelhoff; April 3, 1922 – May 13, 2019) was an American actress, singer, and activist. She began her career as a big band singer in 1939, achieving commercial success in 1945 with two No. 1 recordings, " Sent ...

, Jane Froman

Ellen Jane Froman (November 10, 1907 – April 22, 1980) was an American actress and singer. During her thirty-year career, she performed on stage, radio and television despite chronic health problems due to injuries sustained in a 1943 plane cra ...

, Fats Waller

Thomas Wright "Fats" Waller (May 21, 1904 – December 15, 1943) was an American jazz pianist, organist, composer, violinist, singer, and comedic entertainer. His innovations in the Harlem stride style laid much of the basis for modern jazz pi ...

, Rosemary Clooney

Rosemary Clooney (May 23, 1928 – June 29, 2002) was an American singer and actress. She came to prominence in the early 1950s with the song "Come On-a My House", which was followed by other pop numbers such as " Botch-a-Me", " Mambo Italiano", ...

, and the Mills Brothers

The Mills Brothers, sometimes billed the Four Mills Brothers, and originally known as the Four Kings of Harmony, were an American jazz and traditional pop vocal quartet who made more than 2,000 recordings that sold more than 50 million copies a ...

. In 1939 the Federal Communications Commission

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is an independent agency of the United States federal government that regulates communications by radio, television, wire, satellite, and cable across the United States. The FCC maintains jurisdiction ...

(FCC) ruled that WLW had to reduce its power to 50 kilowatts, partly because it interfered with the broadcasts of other stations, but largely due to its smaller competitors, who complained about the station's technical and commercial advantages with its 500-kilowatt broadcasts.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, WLW resumed its powerful, 500-kilowatt transmissions in cooperation with the U.S. government. The 500-kilowatt transmitter was crated for shipment to Asia, but the war ended before it was shipped. WLW's engineers also built high-power shortwave transmitter

In electronics and telecommunications, a radio transmitter or just transmitter is an electronic device which produces radio waves with an antenna. The transmitter itself generates a radio frequency alternating current, which is applied to the ...

s on a site about north of Cincinnati. Crosley Broadcasting, under contract to the U.S. government, began operating the Bethany Relay Station, which was dedicated on September 23, 1944, to broadcast "Voice of America

Voice of America (VOA or VoA) is the state-owned news network and international radio broadcaster of the United States of America. It is the largest and oldest U.S.-funded international broadcaster. VOA produces digital, TV, and radio content ...

" programming. The relay station's broadcasts continued until 1994.

Crosley's broadcasting company eventually expanded into additional markets. The company was experimenting with television

Television, sometimes shortened to TV, is a telecommunication medium for transmitting moving images and sound. The term can refer to a television set, or the medium of television transmission. Television is a mass medium for advertisin ...

broadcasting as early as 1929, when it received an experimental television license from the Federal Radio Commission (FRC), which later became the FCC. Crosley Broadcasting did not go on-air with regular television programming as WLWT

WLWT (channel 5) is a television station in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States, affiliated with NBC and owned by Hearst Television. The station's studios are located on Young Street, and its transmitter is located on Chickasaw Street, both in the ...

until after Crosley sold the company to Aviation Corporation (Avco

Avco Corporation is a subsidiary of Textron which operates Textron Systems Corporation

and Lycoming.

History

The Aviation Corporation was formed on March 2, 1929, to prevent a takeover of CAM-24 airmail service operator Embry-Riddle Compa ...

) and he had become a member of Avco's board of directors..

Appliance and consumer products manufacturer

Icyball

Icyball is a name given to two early refrigerators, one made by Australian Sir Edward Hallstrom in 1923, and the other design patented by David Forbes Keith of Toronto (filed 1927, granted 1929), and manufactured by American Powel Crosley Jr., ...

" was an early non-electrical refrigeration device. The unit used an evaporative cycle to create cold, and had no moving parts. The dumbbell shaped unit was "charged" by heating one end with a small kerosene heater. Crosley's company sold several hundred thousand Icyball units before discontinuing its manufacture in the late 1930s.

In 1932 Crosley had the idea of putting shelves in the doors of refrigerators. He patented the "Shelvador" refrigerator and launched the new appliance in 1933. At that time it was the only model with shelves in the door. In addition to refrigerators, Crosley's company sold other consumer products that included the "XERVAC," a device purported to "revitalize inactive hair

Hair is a protein filament that grows from follicles found in the dermis. Hair is one of the defining characteristics of mammals.

The human body, apart from areas of glabrous skin, is covered in follicles which produce thick terminal and f ...

cells" and "stimulate hair growth". Crosley also introduced the "Autogym," a motor-driven weight-loss device with a vibrating belt, and the "Go-Bi-Bi," a "rideable baby walker," among other products.Gugin and St. Clair, p. 80.

Baseball team owner and sportsman

In February 1934, Crosley purchased theCincinnati Reds

The Cincinnati Reds are an American professional baseball team based in Cincinnati. They compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the National League (NL) National League Central, Central division and were a charter member of ...

professional baseball team from Sidney Weil, who had lost much of his wealth after the Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange colla ...

. Crosley kept the team from going bankrupt and leaving Cincinnati. He was also owner of the Reds when the team won two National League

The National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, known simply as the National League (NL), is the older of two leagues constituting Major League Baseball (MLB) in the United States and Canada, and the world's oldest extant professional team s ...

titles (in 1939 and 1940) and the World Series in 1940.

Crosley was also a pioneer in broadcasting baseball games on the radio. On May 24, 1935, the first nighttime game in Major League baseball history was held at Cincinnati's Crosley Field

Crosley Field was a Major League Baseball park in Cincinnati, Ohio. It was the home field of the National League's Cincinnati Reds from 1912 through June 24, 1970, and the original Cincinnati Bengals football team, members of the second (1937) an ...

, which was renamed in Crosley's honor after he acquired the team, between the Cincinnati Reds and Philadelphia Phillies

The Philadelphia Phillies are an American professional baseball team based in Philadelphia. They compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member of the National League (NL) National League East, East division. Since 2004, the team's home sta ...

under newly installed electric lighting. With attendance at its evening games more than four times greater that its daytime events, the team's financial position was greatly improved. Crosley also approved baseball's first regularly-scheduled play-by-play broadcasts of all scheduled games on his local station, WSAI

WSAI (1360 AM) is a Cincinnati, Ohio commercial radio station. Owned and operated by iHeartMedia, its studios, as well as those of iHeartMedia's other Cincinnati stations, are in the Towers of Kenwood building next to I-71 in the Kenwood secti ...

, whose call letters stood for "sports and information," and later on WLW. The coverage increased attendance so much that within five years all 16 major league teams had radio broadcasts of every scheduled game.

On a personal level, Crosley was an avid sportsman. Although he never had a pilot's license, Crosley owned several seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tec ...

s, such as the Douglas Dolphin

The Douglas Dolphin is an American amphibious flying boat. While only 58 were built, they served a wide variety of roles including private air yacht, airliner, military transport, and search and rescue.

Design and development

The Dolphin origin ...

, and airplane

An airplane or aeroplane (informally plane) is a fixed-wing aircraft that is propelled forward by thrust from a jet engine, propeller, or rocket engine. Airplanes come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and wing configurations. The broad spe ...

s, including building five Crosley "Moonbeam" airplanes. In addition, Crosley claimed that at one time he was slotted to be a driver in the Indianapolis 500

The Indianapolis 500, formally known as the Indianapolis 500-Mile Race, and commonly called the Indy 500, is an annual automobile race held at Indianapolis Motor Speedway (IMS) in Speedway, Indiana, United States, an enclave suburb of Indi ...

, but that claim was not entirely accurate. He was entered but broke his arm working for Carl Fisher (see above). Crosley was also the owner of luxury yacht

A superyacht or megayacht is a large and luxurious pleasure vessel. There are no official or agreed upon definitions for such yachts, but these terms are regularly used to describe professionally crewed motor or sailing yachts, ranging from to ...

s with powerful engines, and an active fisherman who participated in celebrated tournaments in Sarasota, Florida. He served as president of the Sarasota area's Anglers Club and was a founder of the American Wildlife Institute. Crosley owned several sports, hunting, and fishing camps: Nikassi, an island retreat in Ontario, Canada; Bull Island off the coast of South Carolina; a hunting retreat he called Sleepy Hollow Farm in Jennings County, Indiana, and a Caribbean vacation home at Cat Cays, Bahamas.Banks, "Big Dream, Small Car," p. 33.

Aircraft manufacturer

Sharonville, Ohio

Sharonville is a city largely in Hamilton County, Ohio, Hamilton county in the U.S. state of Ohio. The population was 13,560 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census. Of this, 11,197 lived in Hamilton County and 2,363 lived in the southeast co ...

and was first flown on December 8, 1929. It was designed by Harold D. Hoekstra, an employee of Crosley's when Crosley was president of the Crosley Aircraft Company. (Hoeskstra later became Chief of Engineering and Design for the Federal Aviation Administration

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is the largest transportation agency of the U.S. government and regulates all aspects of civil aviation in the country as well as over surrounding international waters. Its powers include air traffic m ...

.) Unique features of this aircraft are the square tube longerons used in the fuselage construction, use of torque tubes instead of control cable, and the corrugated aluminum ailerons. Original power was supplied by a four-cylinder inverted inline 90 hp Crosley engine. At one time it was also tested with a 110 Warner Scarab engine. N147N reportedly was the first airplane on which the spoilers were tested (in May 1930) as a lateral control device. Five Moonbeams airplanes were produced. The first was a three-place parasol; next, a four-place, high wing cabin model; third and fourth were one place high wings. Due to the Great Depression, planned production did not take place. N147N is the last of these planes in existence. It is housed at the Aviation Museum of Kentucky in Lexington Kentucky

Lexington is a city in Kentucky, United States that is the county seat of Fayette County. By population, it is the second-largest city in Kentucky and 57th-largest city in the United States. By land area, it is the country's 28th-largest ...

.

In 1933 Frenchman Henri Mignet designed the HM.14 "Pou du Ciel" ("Flying Flea"). He envisioned a simple aircraft that amateurs could build, and even teach themselves to fly. In an attempt to render the aircraft stall proof and safe for amateur pilots to fly, Mignet staggered the two main wings. The Mignet-Crosley "Pou du Ciel" is the first HM.14 made and flown in the United States. Edward Nirmaier, a Crosley employee, and two other men built the airplane in November 1935 for Crosley, who believed that the affordable "Flea" could become a popular aircraft in the United States. After several flights, a crash at the Miami Air Races in December 1935 finally grounded the Crosley HM.14. Although the airplane enjoyed a period of intense popularity in France and England, a series of accidents in 1935-36 permanently ruined the airplane's reputation.

In 1933 Frenchman Henri Mignet designed the HM.14 "Pou du Ciel" ("Flying Flea"). He envisioned a simple aircraft that amateurs could build, and even teach themselves to fly. In an attempt to render the aircraft stall proof and safe for amateur pilots to fly, Mignet staggered the two main wings. The Mignet-Crosley "Pou du Ciel" is the first HM.14 made and flown in the United States. Edward Nirmaier, a Crosley employee, and two other men built the airplane in November 1935 for Crosley, who believed that the affordable "Flea" could become a popular aircraft in the United States. After several flights, a crash at the Miami Air Races in December 1935 finally grounded the Crosley HM.14. Although the airplane enjoyed a period of intense popularity in France and England, a series of accidents in 1935-36 permanently ruined the airplane's reputation.

Automaker

Of all Crosley's dreams, success at building an affordable automobile for Americans was possibly the only major one eventually to elude him. In the years leading up to

Of all Crosley's dreams, success at building an affordable automobile for Americans was possibly the only major one eventually to elude him. In the years leading up to World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Crosley developed new products that included reviving one of his earliest endeavors at automobile design and manufacturing. In 1939, when Crosley introduced the low-priced Crosley

Crosley was a small, independent American manufacturer of subcompact cars, bordering on microcars. At first called the Crosley Corporation and later Crosley Motors Incorporated, the Cincinnati, Ohio, firm was active from 1939 to 1952, inter ...

automobiles, he broke with tradition and sold his cars through independent appliance, hardware, and department stores instead of automobile dealerships.Banks, "Big Dream, Small Car," p. 34. See also:

The first Crosley Motors, Inc. automobile made its debut at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway

The Indianapolis Motor Speedway is an automobile racing circuit located in Speedway, Indiana, an enclave suburb of Indianapolis, Indiana. It is the home of the Indianapolis 500 and the Verizon 200, and and formerly the home of the United State ...

on April 28, 1939, to mixed reviews. The compact car

Compact car is a vehicle size class — predominantly used in North America — that sits between subcompact cars and mid-size cars. "Small family car" is a British term and a part of the C-segment in the European car classification. However, p ...

had an wheelbase and a ,

two-cylinder, air cooled Waukesha engine

Waukesha is a brand of large stationary reciprocating engines produced by INNIO Waukesha Gas Engines, a business unit of the INNIO Group.

For 62 years, Waukesha was an independent supplier of gasoline engines, diesel engines, multifuel engines (g ...

. Crosley estimated that his cloth-top car, which weighed less than , could get fifty miles per gallon at speeds of up to fifty miles per hour. The sedan model sold for $325, while the coupe sold for $350. Panel truck and pickup truck models were added to the product line in 1940. During the pre-war period, the company had manufacturing plants in Camp Washington, Ohio

Camp Washington is a city neighborhood of Cincinnati, Ohio, United States. It is located north of Queensgate, east of Fairmount, and west of Clifton and University Heights. The community is a crossing of 19th-century homes and industrial space, ...

; Richmond, Indiana

Richmond is a city in eastern Wayne County, Indiana. Bordering the state of Ohio, it is the county seat of Wayne County and is part of the Dayton, OH Metropolitan Statistical Area In the 2010 census, the city had a population of 36,812. Situa ...

; and Marion, Indiana

Marion is a city in Grant County, Indiana, United States. The population was 29,948 as of the 2010 United States Census. The city is the county seat of Grant County. It is named for Francis Marion, a brigadier general from South Carolina in the ...

. When the onset of war ended all automobile production in the United States in 1942, Crosley had produced 5,757 cars.

After World War II ended, Crosley resumed building its small cars for civilian use. His company's first post-war automobile rolled off the assembly line on May 9, 1946.Banks, "Big Dream, Small Car," pp. 36–37. The new Crosley "CC" model automobile continued the company's pre-war tradition of offering small, lightweight, and low-priced cars. It sold for $850 and got thirty to fifty miles per U.S. gallon. In 1949 Crosley became the first American carmaker to put disc brakes

A disc brake is a type of brake that uses the calipers to squeeze pairs of pads against a disc or a "rotor" to create friction. This action slows the rotation of a shaft, such as a vehicle axle, either to reduce its rotational speed or to hol ...

on all of its models.

Unfortunately for Crosley, fuel economy ceased to be an inducement after gas rationing ended, and American consumers also began to prefer bigger cars. Crosley's best year was 1948, when it sold 24,871 cars, but sales began to fall in 1949. Adding the Crosley "Hotshot" sports model and an all-purpose vehicle called the "Farm-O-Road" model in 1950 did not stop the decline. Only 1,522 Crosley vehicles were sold in 1952. Crosley sold about 84,000 cars before closing down the operation on July 3, 1952. The Crosley plant in Marion, Indiana, was sold to the General Tire and Rubber Company

Continental Tire the Americas, LLC, d.b.a. General Tire, is an American manufacturer of tires for motor vehicles. Founded in 1915 in Akron, Ohio by William Francis O'Neil, Winfred E. Fouse, Charles J. Jahant, Robert Iredell, & H.B. Pushee as ...

.

War-production contractor

Crosley's company was involved in war production planning before December 1941, and like the rest of American industry, it focused on manufacturing war-related products during World War II. The company made a variety of products, including

Crosley's company was involved in war production planning before December 1941, and like the rest of American industry, it focused on manufacturing war-related products during World War II. The company made a variety of products, including proximity fuze

A proximity fuze (or fuse) is a Fuze (munitions), fuze that detonates an Explosive material, explosive device automatically when the distance to the target becomes smaller than a predetermined value. Proximity fuzes are designed for targets such ...

s, experimental military vehicles, radio transceiver

In radio communication, a transceiver is an electronic device which is a combination of a radio ''trans''mitter and a re''ceiver'', hence the name. It can both transmit and receive radio waves using an antenna, for communication purposes. The ...

s, and gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s, among other items.Banks, "Big Dream, Small Car," pp. 34–35. See also:

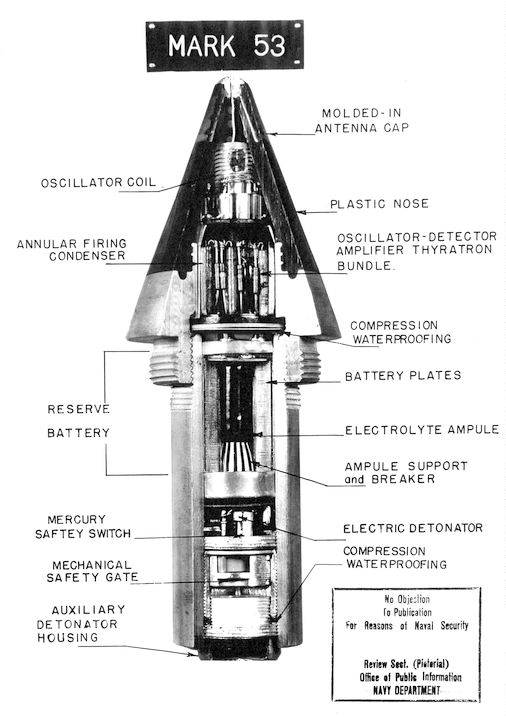

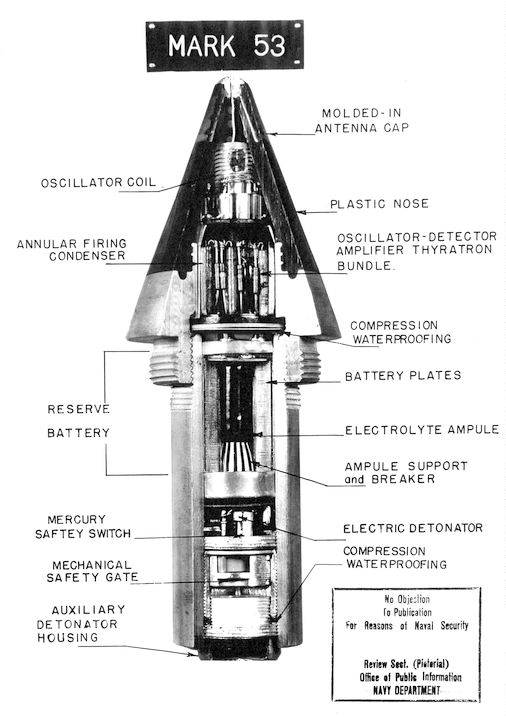

Proximity fuzes

The most significant Crosley's wartime production was theproximity fuze

A proximity fuze (or fuse) is a Fuze (munitions), fuze that detonates an Explosive material, explosive device automatically when the distance to the target becomes smaller than a predetermined value. Proximity fuzes are designed for targets such ...

, which was manufactured by several companies for the military. Crosley's facilities produced more fuzes than any other manufacturer and made several production design innovations. The fuze is widely considered the third most important product development of the war years, ranking behind the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

and radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

.

Ironically, Crosley himself did not have U.S. government security clearance and was not involved with the project. Without government security clearance, Crosley was prohibited from entering the area of his plant that manufactured the fuzes and did not know what top-secret products it produced until the war's end. Production was directed and supervised by Lewis M. Clement, the Crosley company's vice-president of engineering.

James V. Forrestal, U.S. Secretary of the Navy said: "The proximity fuze has helped blaze the trail to Japan. Without the protection this ingenious device has given the surface ships of the Fleet, our westward push could not have been so swift and the cost in men and ships would have been immeasurably greater." George S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, and the Third United States Army in France ...

, Commanding General of the Third Army, remarked: "The funny fuze won the Battle of the Bulge

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive, was the last major German offensive (military), offensive military campaign, campaign on the Western Front (World War II), Western Front during World War II. The battle lasted fr ...

for us. I think that when all armies get this shell we will have to devise some new method of warfare."

Radio transceivers, gun turrets, and other products

Also of significance were the many radio transceivers that Crosley's company manufactured during the war, including 150,000BC-654 The SCR-284 was a World War II era combination transmitter and receiver used in vehicles or fixed ground stations.

History

The Crosley Corporation of Cincinnati, Ohio manufactured the Signal Corps Radio set SCR-284 that consisted of the BC-6 ...

s, a receiver and transmitter that was the main component of the SCR-284 radio set. The Crosley Corporation also made components for Walkie-talkie

A walkie-talkie, more formally known as a handheld transceiver (HT), is a hand-held, portable, two-way radio transceiver. Its development during the Second World War has been variously credited to Donald Hings, radio engineer Alfred J. Gross, ...

transceivers and IFR

In aviation, instrument flight rules (IFR) is one of two sets of regulations governing all aspects of civil aviation aircraft operations; the other is visual flight rules (VFR).

The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration's (FAA) ''Instrument Fly ...

radio guidance equipment, among other products. In addition, Crosley's also manufactured field kitchens, air supply units for Sperry S-1 bombsites (used in B-24 bombers), air conditioning units, Martin PBM Mariner

The Martin PBM Mariner was an American Maritime patrol aircraft, patrol bomber flying boat of World War II and the early Cold War era. It was designed to complement the Consolidated PBY Catalina and Consolidated PB2Y Coronado, PB2Y Coronado in s ...

bow-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s, and quarter-ton trailers. Gun turrets for PT boat

A PT boat (short for patrol torpedo boat) was a motor torpedo boat used by the United States Navy in World War II. It was small, fast, and inexpensive to build, valued for its maneuverability and speed but hampered at the beginning of the wa ...

s and B-24 and B-29 bombers were the company's largest military contract.

Experimental military vehicles

During the war, Crosley's auto manufacturing division, CRAD (for Crosley Radio Auto Division), in Richmond, Indiana, produced experimentalmotorcycles

A motorcycle (motorbike, bike, or trike (if three-wheeled)) is a two or three-wheeled motor vehicle steered by a handlebar. Motorcycle design varies greatly to suit a range of different purposes: long-distance travel, commuting, cruising, ...

, tricycles

A tricycle, sometimes abbreviated to trike, is a human-powered (or gasoline or electric motor powered or assisted, or gravity powered) three-wheeled vehicle.

Some tricycles, such as cycle rickshaws (for passenger transport) and freight trikes ...

, four-wheel-drive vehicles, and continuous track

Continuous track is a system of vehicle propulsion used in tracked vehicles, running on a continuous band of treads or track plates driven by two or more wheels. The large surface area of the tracks distributes the weight of the vehicle b ...

vehicles, including some amphibious models. All of these military prototypes were powered by the two-cylinder boxer engine that had powered the original Crosley automobile. Crosley had nearly 5,000 of these engines on hand when civilian automobile production ceased in 1942, and hoped to put them to use in his miniature war machines.

One vehicle prototype

A prototype is an early sample, model, or release of a product built to test a concept or process. It is a term used in a variety of contexts, including semantics, design, electronics, and Software prototyping, software programming. A prototyp ...

was the 1942/1943 Crosley CT-3 "Pup," a lightweight, single-passenger, four-wheel-drive vehicle that was transportable and air-droppable from a C-47 Skytrain

The Douglas C-47 Skytrain or Dakota (Royal Air Force, RAF, Royal Australian Air Force, RAAF, Royal Canadian Air Force, RCAF, Royal New Zealand Air Force, RNZAF, and South African Air Force, SAAF designation) is a airlift, military transport ai ...

. Six of the Pups were deployed overseas after undergoing tests at Fort Benning

Fort Benning is a United States Army post near Columbus, Georgia, adjacent to the Alabama–Georgia border. Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve component soldiers, retirees and civilian employees ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, but the Pup project was discontinued due to several weak components. Seven of the thirty-seven Pups that were built are known to survive.

Later years

Although Crosley retained ownership of the Cincinnati Reds baseball team and Crosley Motors, he sold his other business interests, including WLW radio and the Crosley Corporation, to the Aviation Corporation (Avco) in 1945. Crosley remained on the Avco board for several years afterward. Avco put Ohio's second television station,WLWT-TV

WLWT (channel 5) is a television station in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States, affiliated with NBC and owned by Hearst Television. The station's studios are located on Young Street, and its transmitter is located on Chickasaw Street, both in the ...

, on the air in 1948, the same year it began manufacturing television sets. Avco manufactured some of the first portable television sets under the Crosley brand name. Crosley ceased to exist as a brand in 1956, when Avco closed the unprofitable product line; however, the Crosley name was so well established that Avco's broadcasting division, owner of WLWT-TV, retained the Crosley name until 1968, seven years after Crosley's death.

Crosley sold Pimlico Plantation, now demolished, in 1942, and Seagate, his winter retreat in Florida in 1947. In 1954 Crosley sold his vacation home at Cat Keys, Bahamas. In 1956 he sold Sleepy Hollow Farm in Jennings County, Indiana, to the state of Indiana for use as a wildlife preserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or o ...

. Bull Island, South Carolina, became part of a national wildlife refuge

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or ...

. It is not known when Crosley sold his vacation retreat in Ontario, Canada.

Death and legacy

Crosley died on March 28, 1961, of aheart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which may tr ...

at the age of 74. He is buried at Spring Grove Cemetery

Spring Grove Cemetery and Arboretum () is a nonprofit rural cemetery and arboretum located at 4521 Spring Grove Avenue, Cincinnati, Ohio. It is the third largest cemetery in the United States, after the Calverton National Cemetery and Abraham L ...

in Cincinnati.

Crosley liked to label himself "the man with 50 jobs in 50 years," a catchy sobriquet

A sobriquet ( ), or soubriquet, is a nickname, sometimes assumed, but often given by another, that is descriptive. A sobriquet is distinct from a pseudonym, as it is typically a familiar name used in place of a real name, without the need of expla ...

that was far from true, although he did have more than a dozen jobs before he got into automobile accessories. Crosley helped quite a few inventors up the ladder of success by buying the rights to their inventions and sharing in the profits. His work provided employment and products for millions of people.

A few of Crosley's company's more noteworthy accomplishments:

* introduced the first compact car to American consumers (in 1939)

* became the second company to install car radio

Vehicle audio is equipment installed in a car or other vehicle to provide in-car entertainment and information for the vehicle occupants. Until the 1950s it consisted of a simple AM radio. Additions since then have included FM radio (1952), 8 ...

s in its models

* the first to introduce push-button car radios

* introduced soap operas to radio broadcasts

* introduced the first non-electric refrigerator (Icyball)

* introduced the first refrigerator with shelves in the door (Shelvador)

* launched the world's most powerful commercial radio station (WLW, at 500 kW)

* installed the first lights on a major league baseball field* introduced facsimile newspaper broadcasts by radio-FAX (Reado)

* the first American carmaker to have disc brakes

A disc brake is a type of brake that uses the calipers to squeeze pairs of pads against a disc or a "rotor" to create friction. This action slows the rotation of a shaft, such as a vehicle axle, either to reduce its rotational speed or to hol ...

on all its models (in 1949)

Part of Crosley's Pinecroft estate, his former Cincinnati, Ohio, home, is the site of Mercy Hospitals West; however, the Franciscan Sisters of the Poor have used his mansion as a retreat since the early 1970s. Seagate, Crosley's former winter retreat on Sarasota Bay in Florida, is operated as an event rental facility. Pinecroft and Seagate have been restored and are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Crosley's farm in Jennings County, Indiana, is the site of the present-day Crosley Fish and Wildlife Area;Banks, "Big Dream, Small Car," p. 36. Bull Island, South Carolina, is part of the Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge

The Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge is a 66,287 acre (267 km²) National Wildlife Refuge in southeastern South Carolina near Awendaw, South Carolina. The refuge lands and waters encompass water impoundments, creeks and bays, eme ...

.

WLW radio continues to operate as an AM station. Crosley's manufacturing plants in Richmond and Marion, Indiana, are still standing, but they no longer produce automobiles. In 1973 a group of Avco executives purchased the Evendale, Ohio, operation of AVCO Electronics Division, a successor to one of Crosley's business ventures, and renamed it the Cincinnati Electronics Corporation. The company manufactured a broad range of sophisticated electronic equipment for communications and space, infrared and radar, and electronic warfare, among others. Since its creation in 1973, Cincinnati Electronics has been acquired by a handful of companies, including GEC Marconi (1981), BAE Systems (1999), CMC Electronics (2001), L-3 Communications (2004–2019), and L3Harris (2019-present).

The present-day Crosley Corporation is not connected to Crosley. An independent appliance distributor formed the current company after purchasing the rights to the name from Avco

Avco Corporation is a subsidiary of Textron which operates Textron Systems Corporation

and Lycoming.

History

The Aviation Corporation was formed on March 2, 1929, to prevent a takeover of CAM-24 airmail service operator Embry-Riddle Compa ...

in 1976. Its appliances are manufactured mostly in North America by Electrolux

Electrolux AB () is a Swedish multinational home appliance manufacturer, headquartered in Stockholm. It is consistently ranked the world's second largest appliance maker by units sold, after Whirlpool.

Electrolux products sell under a variety ...

and Whirlpool Corporation

The Whirlpool Corporation is an American multinational manufacturer and marketer of home appliances, headquartered in Benton Charter Township, Michigan, United States. The Fortune 500 company has annual revenue of approximately $21 billion, ...

. Crosley-branded, top-loading washing machine

A washing machine (laundry machine, clothes washer, washer, or simply wash) is a home appliance used to wash laundry. The term is mostly applied to machines that use water as opposed to dry cleaning (which uses alternative cleaning fluids and ...

s are made by the Whirlpool at its plant in Clyde, Ohio

Clyde is a city in Sandusky County, Ohio, located eight miles southeast of Fremont. The population was 6,325 at the time of the 2010 census. The National Arbor Day Foundation has designated Clyde as a Tree City USA.

The town is known for hav ...

. In 1984, Modern Marketing Concepts, one of the leading U.S. manufacturers of vintage-styled turntables, radios, and other audio electronics, reintroduced Crosley brand name for its Crosley Radio

Crosley Radio is an audio electronic manufacturing company headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky. It is a modern incarnation of the original Crosley Corporation which existed from 1921 to 1956. Modern Marketing Concepts resurrected the Crosle ...

.

Crosley's automobiles and experimental military vehicles are in the collections of several museums. Crosleys are also sought-after vehicles by vintage auto collectors. The Crosley company's Bonzo promotional items and Crosley Pup radios have become valuable as collectibles

A collectable (collectible or collector's item) is any object regarded as being of value or interest to a collector. Collectable items are not necessarily monetarily valuable or uncommon. There are numerous types of collectables and terms t ...

. A papier mâché

Papier may refer to :

*paper in French, Dutch, Afrikaans, Polish or German, word that can be found in the following expressions:

**Papier-mâché, a construction material made of pieces of paper stuck together using a wet paste

**Papier collé, a p ...

Crosley Bonzo is on display at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =