Pope Leo X on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pope Leo X ( it, Leone X; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the

Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici was born on 11 December 1475 in the

Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici was born on 11 December 1475 in the

In response to concerns about misconduct from some indulgence preachers, in 1517

In response to concerns about misconduct from some indulgence preachers, in 1517

Leo X's love for all forms of art stemmed from the humanistic education he received in

Leo X's love for all forms of art stemmed from the humanistic education he received in

Even those who defend him against the more outlandish attacks on his character acknowledge that he partook of entertainment such as masquerades, "jests," fowling, and hunting boar and other wild beasts. According to one biographer, he was "engrossed in idle and selfish amusements".

Leo indulged buffoons at his Court, but also tolerated behavior which made them the object of ridicule. One case concerned the conceited ''improvisatore'' Giacomo Baraballo, Abbot of Gaeta, who was the butt of a burlesque procession organised in the style of an ancient Roman triumph. Baraballo was dressed in festal robes of velvet and with ermine and presented to the pope. He was then taken to the piazza of St Peter's and was mounted on the back of Hanno, a white elephant, the gift of King

Even those who defend him against the more outlandish attacks on his character acknowledge that he partook of entertainment such as masquerades, "jests," fowling, and hunting boar and other wild beasts. According to one biographer, he was "engrossed in idle and selfish amusements".

Leo indulged buffoons at his Court, but also tolerated behavior which made them the object of ridicule. One case concerned the conceited ''improvisatore'' Giacomo Baraballo, Abbot of Gaeta, who was the butt of a burlesque procession organised in the style of an ancient Roman triumph. Baraballo was dressed in festal robes of velvet and with ermine and presented to the pope. He was then taken to the piazza of St Peter's and was mounted on the back of Hanno, a white elephant, the gift of King

Leo called Janus Lascaris to Rome to give instruction in Greek, and established a Greek printing-press from which the first Greek book printed at Rome appeared in 1515. He made Raphael custodian of the classical antiquities of Rome and the vicinity, the ancient monuments of which formed the subject of a famous letter from Raphael to the pope in 1519. The distinguished Latinists Pietro Bembo and

Leo called Janus Lascaris to Rome to give instruction in Greek, and established a Greek printing-press from which the first Greek book printed at Rome appeared in 1515. He made Raphael custodian of the classical antiquities of Rome and the vicinity, the ancient monuments of which formed the subject of a famous letter from Raphael to the pope in 1519. The distinguished Latinists Pietro Bembo and

vol.I (1507–1521)

an

vol.2 (1521–1530)

from

Vita de Leonis X

life in Latin by

Henry VIII to Pope Leo X. 21 May 1521Leo_X_to_Frederic,_Elector_of_Saxony

._Rome,_8_July_1520.html" ;"title="Elector of Saxony">Leo X to Frederic, Elector_of_Saxony">Leo_X_to_Frederic,_Elector_of_Saxony

._Rome,_8_July_1520br>Paradoxplace_Medici_Popes'_Page

{{DEFAULTSORT:Leo_10 Pope_Leo_X.html" ;"title="Elector of Saxony

. Rome, 8 July 1520">Elector of Saxony">Leo X to Frederic, Elector of Saxony

. Rome, 8 July 1520br>Paradoxplace Medici Popes' Page

{{DEFAULTSORT:Leo 10 Pope Leo X"> Cardinal-nephews Italian popes Clergy from Florence House of Medici 1475 births 1521 deaths Renaissance Papacy Burials at Santa Maria sopra Minerva Popes Simony 16th-century popes Italian art patrons Deaths from pneumonia in Lazio

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

and ruler of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political and banking Medici family of Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

, Giovanni was the second son of Lorenzo de' Medici, ruler of the Florentine Republic, and was elevated to the cardinalate

The College of Cardinals, or more formally the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. its current membership is , of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Cardinals are ap ...

in 1489. Following the death of Pope Julius II

Pope Julius II ( la, Iulius II; it, Giulio II; born Giuliano della Rovere; 5 December 144321 February 1513) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1503 to his death in February 1513. Nicknamed the Warrior Pope or t ...

, Giovanni was elected pope after securing the backing of the younger members of the Sacred College

The College of Cardinals, or more formally the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. its current membership is , of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Cardinals are app ...

. Early on in his rule he oversaw the closing sessions of the Fifth Council of the Lateran, but struggled to implement the reforms agreed. In 1517 he led a costly war that succeeded in securing his nephew Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici as Duke of Urbino, but reduced papal finances.

In Protestant circles, Leo is associated with granting indulgences

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (, from , 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for sins". The ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' describes an indulgence as "a remission before God o ...

for those who donated to reconstruct St. Peter's Basilica, a practice that was soon challenged by Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

's '' 95 Theses''. Leo rejected the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

, and his Papal bull of 1520, '' Exsurge Domine'', condemned Luther's condemnatory stance, rendering ongoing communication difficult.

He borrowed and spent money without circumspection and was a significant patron of the arts. Under his reign, progress was made on the rebuilding of St. Peter's Basilica and artists such as Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, better known as Raphael (; or ; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form, ease of composition, and visual ...

decorated the Vatican rooms. Leo also reorganised the Roman University, and promoted the study of literature, poetry and antiquities. He died in 1521 and is buried in Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome. He was the last pope not to have been in priestly orders at the time of his election to the papacy.

Early life

Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici was born on 11 December 1475 in the

Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici was born on 11 December 1475 in the Republic of Florence

The Republic of Florence, officially the Florentine Republic ( it, Repubblica Fiorentina, , or ), was a medieval and early modern state that was centered on the Italian city of Florence in Tuscany. The republic originated in 1115, when the Fl ...

, the second son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, head of the Florentine Republic, and Clarice Orsini. From an early age Giovanni was destined for an ecclesiastical career. He received the tonsure at the age of seven and was soon granted rich benefices and preferments.

His father, Lorenzo de' Medici, was worried about his character early on and wrote a letter to Giovanni to warn him to avoid vice and luxury upon the beginning of his ecclesiastical career. Here is a notable excerpt: "There is one rule which I would recommend to your attention in preference to all others. Rise early in the morning. This will not only contribute to your health, but will enable you to arrange and expedite the business of the day; and as there are various duties incident to".

Cardinal

His father prevailed on his relative Pope Innocent VIII to name himcardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**'' Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**'' Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, t ...

of Santa Maria in Domnica

The Minor Basilica of St. Mary in Domnica alla Navicella (Basilica Minore di Santa Maria in Domnica alla Navicella), or simply Santa Maria in Domnica or Santa Maria alla Navicella, is a Roman Catholic basilica in Rome, Italy, dedicated to the Bl ...

on 8 March 1488 when he was age 13, although he was not allowed to wear the insignia or share in the deliberations of the college until three years later. Meanwhile, he received an education at Lorenzo's humanistic court

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in acco ...

under such men as Angelo Poliziano

Agnolo (Angelo) Ambrogini (14 July 1454 – 24 September 1494), commonly known by his nickname Poliziano (; anglicized as Politian; Latin: '' Politianus''), was an Italian classical scholar and poet of the Florentine Renaissance. His sc ...

, Pico della Mirandola, Marsilio Ficino and Bernardo Dovizio Bibbiena

Bernardo Dovizi of Bibbiena (4 August 1470 – 9 November 1520) was an Italian cardinal and comedy writer, known best as Cardinal Bibbiena, for the town of Bibbiena, where he was born.

Biography

He received a substantial literary training, ...

. From 1489 to 1491 he studied theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing th ...

and canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is t ...

at Pisa.

On 23 March 1492, he was formally admitted into the Sacred College of Cardinals and took up his residence at Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, receiving a letter of advice from his father. The death of Lorenzo on the following 8 April temporarily recalled the 16-year-old Giovanni to Florence. He returned to Rome to participate in the conclave of 1492

The 1492 papal conclave (6–11 August) was convened after the death of Pope Innocent VIII (25 July 1492). It was the first papal conclave to be held in the Sistine Chapel.

Cardinal Roderic Borja was elected unanimously on the fourth ballot as Po ...

which followed the death of Innocent VIII, and unsuccessfully opposed the election of Cardinal Borgia (elected as Pope Alexander VI).

He subsequently made his home with his elder brother Piero in Florence throughout the agitation of Savonarola

Girolamo Savonarola, OP (, , ; 21 September 1452 – 23 May 1498) or Jerome Savonarola was an Italian Dominican friar from Ferrara and preacher active in Renaissance Florence. He was known for his prophecies of civic glory, the destruction ...

and the invasion of Charles VIII of France, until the uprising of the Florentines and the expulsion of the Medici in November 1494. While Piero found refuge at Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

and Urbino, Giovanni traveled in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, and in France.

In May 1500, he returned to Rome, where he was received with outward cordiality by Pope Alexander VI, and where he lived for several years immersed in art and literature. In 1503 he welcomed the accession of Pope Julius II

Pope Julius II ( la, Iulius II; it, Giulio II; born Giuliano della Rovere; 5 December 144321 February 1513) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 1503 to his death in February 1513. Nicknamed the Warrior Pope or t ...

to the pontificate; the death of Piero de' Medici in the same year made Giovanni head of his family. On 1 October 1511 he was appointed papal legate of Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label= Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different na ...

and the Romagna, and when the Florentine republic declared in favour of the schismatic Pisans, Julius II sent Giovanni (as legate) with the papal army venturing against the French. The French won a major battle and captured Giovanni. This and other attempts to regain political control of Florence were frustrated until a bloodless revolution permitted the return of the Medici. Giovanni's younger brother Giuliano was placed at the head of the republic, but Giovanni managed the government.

Pope

Papal election

Giovanni was elected pope on 9 March 1513, and this was proclaimed two days later. The absence of the French cardinals effectively reduced the election to a contest between Giovanni (who had the support of the younger and noble members of the college) and Raffaele Riario (who had the support of the older group). On 15 March 1513, he was ordained priest, and consecrated as bishop on 17 March. He was crowned Pope on 19 March 1513 at the age of 37. He was the last non-priest to be elected pope.War of Urbino

Leo had intended his younger brother Giuliano and his nephew Lorenzo for brilliant secular careers. He had named them Roman patricians; the latter he had placed in charge of Florence; the former, for whom he planned to carve out a kingdom in central Italy of Parma, Piacenza, Ferrara and Urbino, he had taken with himself to Rome and married to Filiberta of Savoy. The death of Giuliano in March 1516, however, caused the pope to transfer his ambitions to Lorenzo. At the very time (December 1516) that peace between France, Spain, Venice and the Empire seemed to give some promise of aChristendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

united against the Turks, Leo obtained 150,000 ducats towards the expenses of the expedition from Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

, in return for which he entered the imperial league of Spain and England against France.

The war lasted from February to September 1517 and ended with the expulsion of the duke and the triumph of Lorenzo; but it revived the policy of Alexander VI, increased brigandage and anarchy in the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

, hindered the preparations for a crusade and wrecked the papal finances. Francesco Guicciardini

Francesco Guicciardini (; 6 March 1483 – 22 May 1540) was an Italian historian and statesman. A friend and critic of Niccolò Machiavelli, he is considered one of the major political writers of the Italian Renaissance. In his masterpiece, ''T ...

reckoned the cost of the war to Leo at the sum of 800,000 ducats. Ultimately, however, Lorenzo was confirmed as the new duke of Urbino.

Plans for a Crusade

The war of Urbino was further marked by a crisis in the relations between pope and cardinals. The sacred college had allegedly grown very worldly and troublesome since the time of Sixtus IV, and Leo took advantage of a plot by several of its members to poison him, not only to inflict exemplary punishments by executing one (Alfonso Petrucci

Alfonso Petrucci (c. 1491 – July 16, 1517) was an Italian nobleman, born to the Petrucci Family. He was the son of Pandolfo Petrucci. In 1511, he was made a cardinal, which gave the Petrucci dynasty some influence within the church.

He was se ...

) and imprisoning several others, but also to make radical changes in the college.

On 3 July 1517 he published the names of thirty-one new cardinals, a number almost unprecedented in the history of the papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

. Among the nominations were such notable men such as Lorenzo Campeggio, Giambattista Pallavicini, Adrian of Utrecht, Thomas Cajetan, Cristoforo Numai

Cristoforo Numai (died 23 March 1528) was an Italian Franciscan, who became minister general of the Friars Minor and a cardinal.

Life

A nativ eof Forlì, his date of birth is uncertain. In his youth he studied at Bologna and, after joining the ...

and Egidio Canisio

Giles Antonini, O.E.S.A., commonly referred to as Giles of Viterbo ( la, Ægidius Viterbensis, it, Egidio da Viterbo), was a 16th-century Italian Augustinian friar, bishop of Viterbo and cardinal, a reforming theologian, orator, humanist and po ...

. The naming of seven members of prominent Roman families, however, reversed the policy of his predecessor which had kept the political factions of the city out of the Curia. Other promotions were for political or family considerations or to secure money for the war against Urbino. The pope was accused of having exaggerated the conspiracy of the cardinals for purposes of financial gain, but most of such accusations appear unsubstantiated.

Leo, meanwhile, felt the need of staying the advance of the Ottoman sultan, Selim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite las ...

, who was threatening eastern Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, and made elaborate plans for a crusade. A truce was to be proclaimed throughout Christendom; the pope was to be the arbiter of disputes; the emperor and the king of France were to lead the army; England, Spain and Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

were to furnish the fleet; and the combined forces were to be directed against Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

. Papal diplomacy

Diplomacy comprises spoken or written communication by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.Ronald Peter Barston, ''Modern diplomacy'', Pearson Education, 2006, p. ...

in the interests of peace failed, however; Cardinal Wolsey made England, not the pope, the arbiter between France and the Empire; and much of the money collected for the crusade from tithes and indulgences was spent in other ways.

In 1519 Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

concluded a three years' truce with Selim I, but the succeeding sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, renewed the war in June 1521 and on 28 August captured the citadel of Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; names in other languages) is the capital and largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and the crossroads of the Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. Nearly 1,166,763 mi ...

. The pope was greatly alarmed, and although he was then involved in war with France he sent about 30,000 ducats to the Hungarians. Leo treated the Eastern Catholic Greeks with great loyalty, and by bull of 18 May 1521 forbade Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

clergy to celebrate mass in Greek churches and Latin bishops to ordain Greek clergy. These provisions were later strengthened by Clement VII and Paul III and went far to settle the constant disputes between the Latins and Uniate Greeks.

Protestant Reformation

Leo was disturbed throughout his pontificate by schism, especially theReformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

sparked by Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

.

In response to concerns about misconduct from some indulgence preachers, in 1517

In response to concerns about misconduct from some indulgence preachers, in 1517 Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

wrote his '' Ninety-five Theses'' on the topic of indulgences. The resulting pamphlet spread Luther's ideas throughout Germany and Europe. Leo failed to fully comprehend the importance of the movement, and in February 1518 he directed the vicar-general of the Augustinians to impose silence on his monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedic ...

s.

On 24 May, Luther sent an explanation of his theses to the pope; on 7 August he was summoned to appear at Rome. An arrangement was effected, however, whereby that summons was cancelled, and Luther went instead to Augsburg

Augsburg (; bar , Augschburg , links=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swabian_German , label=Swabian German, , ) is a city in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, around west of Bavarian capital Munich. It is a university town and regional seat of the ' ...

in October 1518 to meet the papal legate, Cardinal Cajetan; but neither the arguments of the cardinal, nor Leo's dogmatic papal bull of 9 November requiring all Christians to believe in the pope's power to grant indulgences, moved Luther to retract. A year of fruitless negotiations followed, during which the controversy took popular root across the German states.

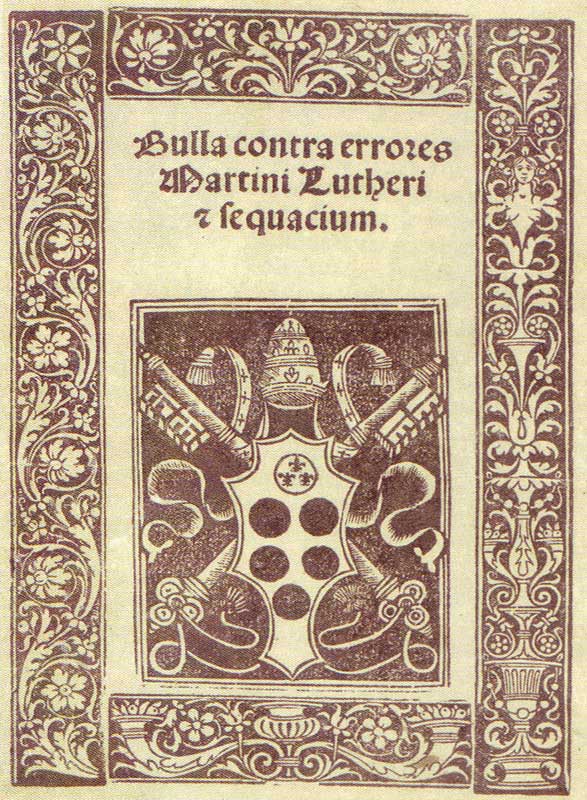

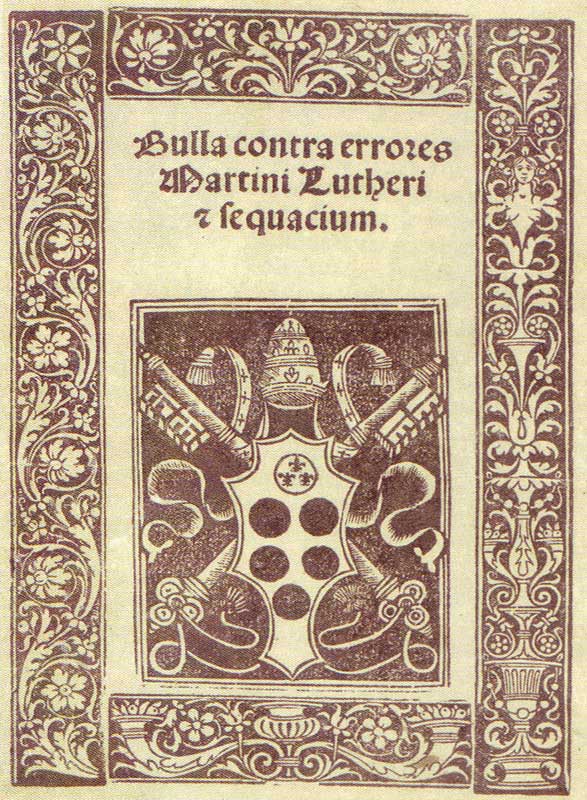

A further papal bull of 15 June 1520, '' Exsurge Domine'' or ''Arise, O Lord'', condemned forty-one propositions extracted from Luther's teachings, and was taken to Germany by Eck in his capacity as apostolic nuncio. Leo followed by formally excommunicating Luther by the bull '' Decet Romanum Pontificem'' or ''It Pleases the Roman Pontiff'', on 3 January 1521. In a brief the Pope also directed Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor to take energetic measures against heresy.

It was also under Leo that Lutheranism spread into Scandinavia. The pope had repeatedly used the rich northern benefices to reward members of the Roman curia, and towards the close of the year 1516 he sent the impolitic Arcimboldi as papal nuncio to Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

to collect money for St Peter's. This led to the Reformation in Denmark. King Christian II took advantage of the growing dissatisfaction of the native clergy toward the papal government, and of Arcimboldi's interference in the Swedish revolt, to expel the nuncio and summon Lutheran theologians to Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan a ...

in 1520. Christian approved a plan by which a formal state church should be established in Denmark, all appeals to Rome should be abolished, and the king and diet should have final jurisdiction in ecclesiastical causes. Leo sent a new nuncio to Copenhagen (1521) in the person of the Minorite Francesco de Potentia, who readily absolved the king and received the bishopric of Skara. The pope or his legate, however, took no steps to correct abuses or otherwise discipline the Scandinavian churches.

Other activities

Consistories

The pope created 42 new cardinals in eight consistories including two cousins (one who would become his successor Pope Clement VII) and a nephew. He also elevated Adriaan Florensz Boeyens into the cardinalate who would become his immediate successor Pope Adrian VI. Leo X's consistory of 1 July 1517 saw 31 cardinals created, and this remained the largest allocation of cardinals in one consistory untilPope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

named 42 cardinals in 2001.

Canonizations

Pope Leo X canonized eleven individuals during his reign with seven of those being a group cause of martyrs. The most notable canonization from his papacy was that of Francis of Paola on 1 May 1519.Final years

That Leo did not do more to check the anti-papal rebellion in Germany and Scandinavia is to be partially explained by the political complications of the time, and by his own preoccupation with papal and Medicean politics in Italy. The death of the emperor Maximilian in 1519 had seriously affected the situation. Leo vacillated between the powerful candidates for the succession, allowing it to appear at first that he favoured Francis or a minor German prince. He finally accepted Charles of Spain as inevitable. Leo was now eager to unite Ferrara, Parma and Piacenza to the States of the Church (The Papal States). An attempt late in 1519 to seize Ferrara failed, and the pope recognized the need for foreign aid. In May 1521 a treaty of alliance was signed at Rome between him and the emperor. Milan andGenoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

were to be taken from France and restored to the Empire, and Parma and Piacenza were to be given to the Church on the expulsion of the French. The expense of enlisting 10,000 Swiss was to be borne equally by Pope and emperor. Charles V took Florence and the Medici family under his protection and promised to punish all enemies of the Catholic faith. Leo agreed to invest Charles V with the Kingdom of Naples, to crown him Holy Roman Emperor, and to aid in a war against Venice. It was provided that England and the Swiss might also join the league. Henry VIII announced his adherence in August 1521. Francis I had already begun war with Charles V in Navarre, and in Italy, too, the French made the first hostile movement on 23 June 1521. Leo at once announced that he would excommunicate the king of France and release his subjects from their allegiance unless Francis I laid down his arms and surrendered Parma and Piacenza to the Church. The pope lived to hear the joyful news of the capture of Milan from the French and of the occupation by papal troops of the long-coveted provinces (November 1521).

Having fallen ill with bronchopneumonia, Pope Leo X died on 1 December 1521, so suddenly that the last sacraments could not be administered; but the contemporary suspicions of poison were unfounded. He was buried in Santa Maria sopra Minerva.

Character, interests and talents

General assessment

Leo has been criticized for his handling of the events of the papacy. He had a musical and pleasant voice and a cheerful temper. He was eloquent in speech and elegant in his manners and epistolary style. He enjoyed music and the theatre, art and poetry, the masterpieces of the ancients and the creations of his contemporaries, especially those seasoned with wit and learning. He especially delighted in ex temporeLatin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

verse-making (at which he excelled) and cultivated ''improvisatori''. He is said to have stated, "Let us enjoy the papacy since God has given it to us", Ludwig von Pastor

Ludwig Pastor, later Ludwig von Pastor, Freiherr von Campersfelden (31 January 1854 – 30 September 1928), was a German historian and a diplomat for Austria. He became one of the most important Roman Catholic historians of his time and is most no ...

says that it is by no means certain that he made the remark; and historian Klemens Löffler says that "the Venetian ambassador who related this of him was not unbiased, nor was he in Rome at the time." However, there is no doubt that he was by nature pleasure-loving and that the anecdote reflects his casual attitude to the high and solemn office to which he had been called. On the other hand, in spite of his worldliness, Leo prayed, fasted, went to confession before celebrating Mass in public, and conscientiously participated in the religious services of the Church. To the virtues of liberality, charity, and clemency he added the Machiavellian qualities of deception and shrewdness, so highly esteemed by the princes of his time.

The character of Leo X was formerly assailed by lurid aspersions of debauchery, murder, impiety, and atheism. In the 17th century it was estimated that 300 or 400 writers, more or less, reported (on the authority of a single polemical anti-Catholic source) a story that when someone had quoted to Leo a passage from one of the Four Evangelists, he had replied that it was common knowledge "how profitable that fable of Christe hath ben to us and our companie." These aspersions and more were examined by William Roscoe in the 19th century (and again by Ludwig von Pastor

Ludwig Pastor, later Ludwig von Pastor, Freiherr von Campersfelden (31 January 1854 – 30 September 1928), was a German historian and a diplomat for Austria. He became one of the most important Roman Catholic historians of his time and is most no ...

in the 20th) and rejected. Nevertheless, even the eminent philosopher David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" '' Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment ph ...

, while claiming that Leo was too intelligent to believe in Catholic doctrine, conceded that he was "one of the most illustrious princes that ever sat on the papal throne. Humane, beneficent, generous, affable; the patron of every art, and friend of every virtue". Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

, in a conciliatory letter to Leo, himself testified to Leo's universal reputation for morality:

The final report of the Venetian ambassador Marino Giorgi Marino, Mariño or Maryino may refer to:

Places

* Marino, Lazio, a town in the province of Rome, Italy

* Marino, South Australia, a suburb of Adelaide

** Marino Conservation Park

** Marino Rocks Greenway, a cycling route

** Marino Rocks railway st ...

supports Hume's assessment of affability, and testifies to the range of Leo's talents. Bearing the date of March 1517 it indicates some of his predominant characteristics:

Leo is the fifth of the six popes who are unfavorably profiled by historian Barbara Tuchman

Barbara Wertheim Tuchman (; January 30, 1912 – February 6, 1989) was an American historian and author. She won the Pulitzer Prize twice, for ''The Guns of August'' (1962), a best-selling history of the prelude to and the first month of Worl ...

in ''The March of Folly

''The March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam'' is a book by Barbara W. Tuchman, an American historian and author. It was published on March 19, 1984, by Knopf in New York.

Summary

The book is about "one of the most compelling paradoxes of histor ...

'', and who are accused by her of precipitating the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

. Tuchman describes Leo as a cultured – if religiously devout – hedonist.

Intellectual interests

Leo X's love for all forms of art stemmed from the humanistic education he received in

Leo X's love for all forms of art stemmed from the humanistic education he received in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

, his studies in Pisa and his extensive travel throughout Europe when a youth. He loved the Latin poems of the humanists, the tragedies of the Greeks and the comedies of Cardinal Bibbiena

Bernardo Dovizi of Bibbiena (4 August 1470 – 9 November 1520) was an Italian cardinal and comedy writer, known best as Cardinal Bibbiena, for the town of Bibbiena, where he was born.

Biography

He received a substantial literary training, ...

and Ariosto, while relishing the accounts sent back by the explorers of the New World. Yet "Such a humanistic interest was itself religious. ... In the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

, the vines of the classical world and the Christian world, of Rome, were seen as intertwined. It was a historically minded culture where artists' representations of Cupid and the Madonna, of Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the ...

and St. Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupation ...

could exist side-by-side".

Love of music

Pastor says that "From his youth, Leo, who had a fine ear and a melodious voice, loved music to the pitch of fanaticism". As pope he procured the services of professional singers, instrumentalists and composers from as far away as France, Germany and Spain. Next to goldsmiths, the highest salaries recorded in the papal accounts are those paid to musicians, who also received largesse from Leo's private purse. Their services were retained not so much for the delectation of Leo and his guests at private social functions as for the enhancement of religious services on which the pope placed great store. The standard of singing of the papal choir was a particular object of Leo's concern, with French, Dutch, Spanish and Italian singers being retained. Large sums of money were also spent on the acquisition of highly ornamented musical instruments, and he was especially assiduous in securing musical scores from Florence. He also fostered technical improvements developed for the diffusion of such scores. Ottaviano Petrucci, who had overcome practical difficulties in the way of using movable type to print musical notation, obtained from Leo X the exclusive privilege of printing organ scores (which, according to the papal brief, "adds greatly to the dignity of divine worship") for a period for 15 years from 22 October 1513. In addition to fostering the performance of sung Masses, he promoted the singing of the Gospel in Greek in his private chapel.Unworthy pursuits

Even those who defend him against the more outlandish attacks on his character acknowledge that he partook of entertainment such as masquerades, "jests," fowling, and hunting boar and other wild beasts. According to one biographer, he was "engrossed in idle and selfish amusements".

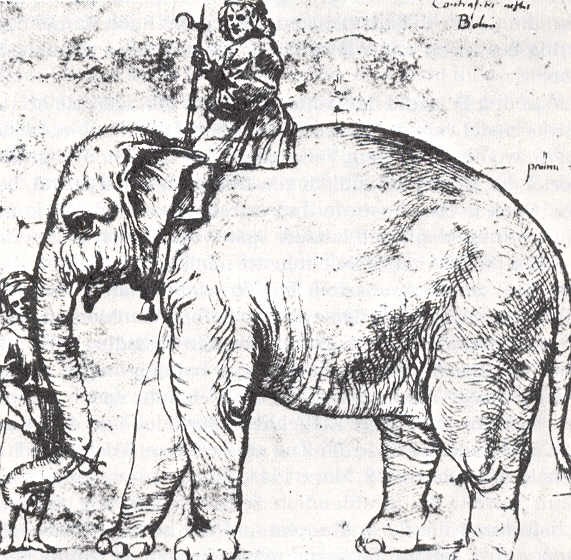

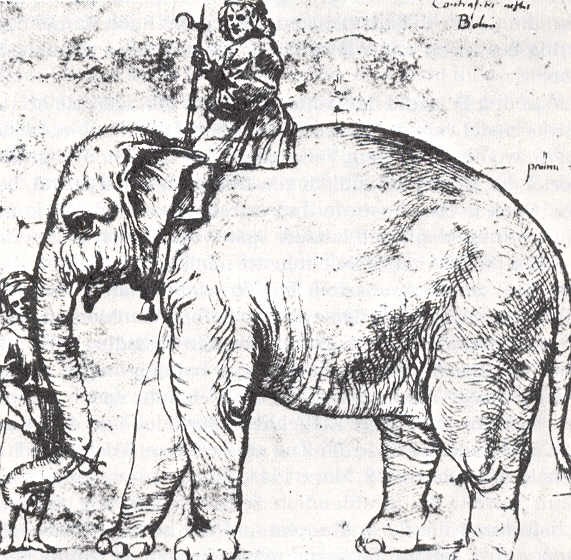

Leo indulged buffoons at his Court, but also tolerated behavior which made them the object of ridicule. One case concerned the conceited ''improvisatore'' Giacomo Baraballo, Abbot of Gaeta, who was the butt of a burlesque procession organised in the style of an ancient Roman triumph. Baraballo was dressed in festal robes of velvet and with ermine and presented to the pope. He was then taken to the piazza of St Peter's and was mounted on the back of Hanno, a white elephant, the gift of King

Even those who defend him against the more outlandish attacks on his character acknowledge that he partook of entertainment such as masquerades, "jests," fowling, and hunting boar and other wild beasts. According to one biographer, he was "engrossed in idle and selfish amusements".

Leo indulged buffoons at his Court, but also tolerated behavior which made them the object of ridicule. One case concerned the conceited ''improvisatore'' Giacomo Baraballo, Abbot of Gaeta, who was the butt of a burlesque procession organised in the style of an ancient Roman triumph. Baraballo was dressed in festal robes of velvet and with ermine and presented to the pope. He was then taken to the piazza of St Peter's and was mounted on the back of Hanno, a white elephant, the gift of King Manuel I of Portugal

Manuel I (; 31 May 146913 December 1521), known as the Fortunate ( pt, O Venturoso), was King of Portugal from 1495 to 1521. A member of the House of Aviz, Manuel was Duke of Beja and Viseu prior to succeeding his cousin, John II of Portuga ...

. The magnificently ornamented animal was then led off in the direction of the Capitol to the sound of drums and trumpets. But while crossing the bridge of Sant'Angelo over the Tiber

The Tiber ( ; it, Tevere ; la, Tiberis) is the third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by th ...

, the elephant, already distressed by the noise and confusion around him, shied violently, throwing his passenger onto the muddy riverbank below.

Sexuality

Leo's most recent biographer, Carlo Falconi, says Leo hid a private life of moral irregularity behind a mask of urbanity. Scabrous verse libels of the type known as pasquinades were particularly abundant during the conclave which followed Leo's death in 1521 and made imputations about Leo's unchastity, implying or assertinghomosexuality

Homosexuality is Romance (love), romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or Human sexual activity, sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romant ...

. Suggestions of homosexual attraction appear in works by two contemporary historians, Francesco Guicciardini

Francesco Guicciardini (; 6 March 1483 – 22 May 1540) was an Italian historian and statesman. A friend and critic of Niccolò Machiavelli, he is considered one of the major political writers of the Italian Renaissance. In his masterpiece, ''T ...

and Paolo Giovio. Zimmerman notes Giovio's "disapproval of the pope's familiar banter with his chamberlains – handsome young men from noble families – and the advantage he was said to take of them."

Luther spent a month in Rome in 1510, three years before Leo became pontiff, and was disillusioned at the corruption he found there. In 1520, the year before his excommunication from the Catholic Church, Luther claimed that Leo lived a "blameless life." However, Luther later distanced himself from this claim and alleged in 1531 that Leo had vetoed a measure that cardinals should restrict the number of boys they kept for their pleasure, "otherwise it would have been spread throughout the world how openly and shamelessly the pope and the cardinals in Rome practice sodomy."; This allegation (made in the pamphlet ''Warnunge D. Martini Luther/ An seine lieben Deudschen'', Wittenberg, 1531) is in stark contrast to Luther's earlier praise of Leo's "blameless life" in a conciliatory letter of his to the pope dated 6 September 1520 and published as a preface to his ''Freedom of a Christian''. See on this, . Against this allegation is the papal bull ''Supernae dispositionis arbitrio'' from 1514 which, ''inter alia'', required cardinals to live "... soberly, chastely, and piously, abstaining not only from evil but also from every appearance of evil" and a contemporary and eye-witness at Leo's Court (Matteo Herculaneo), emphasized his belief that Leo was chaste all his life.

Historians have dealt with the issue of Leo's sexuality at least since the late 18th century, and few have given credence to the imputations made against him in his later years and decades following his death, or else have at least regarded them as unworthy of notice; without necessarily reaching conclusions on whether he was homosexual. Those who stand outside this consensus generally fall short of concluding with certainty that Leo was unchaste during his pontificate. Joseph McCabe accused Pastor of untruthfulness and Vaughan of lying in course of their treatment of the evidence, pointing out that Giovio and Guicciardini seemed to share the belief that Leo engaged in "unnatural vice" (homosexuality) while pope.

Benevolence

Leo X made charitable donations of more than 6,000 ducats annually to retirement homes, hospitals, convents, discharged soldiers, pilgrims, poor students, exiles, cripples, and the sick and unfortunate.Death and legacy

Death

Pope Leo X died fairly suddenly of pneumonia at the age of 45 on 1 December 1521 and was buried in Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome. His death came just 10 months after he had excommunicatedMartin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

, the seminal figure in the Protestant Reformation, who was accused of 41 errors in his teachings.

Failure to stem the Reformation

Possibly the most lasting legacy of the reign of Pope Leo X was his perceived failure not just to stem the Reformation but to fuel it. A key issue was that his pontificate failed to bring about the reforms decreed by the Fifth Lateran Council (held between 1512 and 1517) which aimed to deal with many of their political problems as well as to reform Christendom, specifically relating to the papacy, cardinals, and curia. Some believe enforcing these decrees may have been enough to dampen support for radical challenges to church authority. But instead under his leadership, Rome's fiscal and political problems were deepened. A major contributor was his lavish spending (especially on the arts and himself) which led the papal treasury into mounting debt and his decision to authorize the sale of indulgences. The exploitation of people and corruption of religious principles linked to the practice of selling indulgences quickly became the key stimulus for the onset of the Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther's '' 95 Theses'', otherwise entitled "Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences", was posted on a Church door in Wittenberg, Germany in October 1517 just seven months after the Lateran V was completed. But Pope Leo X's attempt to prosecute Luther's teaching on indulgences, and to eventually excommunicate him in January 1521, did not get rid of Lutheran doctrine but had the opposite effect of further splintering the Western church.Excessive spending

Leo was renowned for spending money lavishly on the arts; on charities; on benefices for his friends, relatives, and even people he barely knew; on dynastic wars, such as the War of Urbino; and on his own personal luxury. Within two years of becoming Pope, Leo X spent all of the treasure amassed by the previous Pope, the frugal Julius II, and drove the Papacy into deep debt. By the end of his pontificate in 1521, the papal treasury was 400,000 ducats in debt. This debt contributed not only to the calamities of Leo's own pontificate (particularly the sale of indulgences that precipitatedProtestantism

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

) but severely constrained later pontificates (Pope Adrian VI; and Leo's beloved cousin, Clement VII) and forced austerity measures.

Leo X's personal spending was likewise vast. For 1517, his personal income is recorded as 580,000 ducats, of which 420,000 came from the states of the Church, 100,000 from annates

Annates ( or ; la, annatae, from ', "year") were a payment from the recipient of an ecclesiastical benefice to the ordaining authorities. Eventually, they consisted of half or the whole of the first year's profits of a benefice; after the appropr ...

, and 60,000 from the composition tax instituted by Sixtus IV. These sums, together with the considerable amounts accruing from indulgences, jubilees, and special fees, vanished as quickly as they were received. To remain financially solvent, the Pope resorted to desperate measures: instructing his cousin, Cardinal Giulio de' Medici

Pope Clement VII ( la, Clemens VII; it, Clemente VII; born Giulio de' Medici; 26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 November 1523 to his death on 25 September 1534. Deemed "the ...

, to pawn the Papal jewels; palace furniture; tableware; and even statues of the apostles. Additionally, Leo sold cardinals' hats; memberships to a fraternal order he invented in 1520, the ''Papal Knights of St. Peter and St. Paul''; and borrowed such immense sums from bankers that upon his death, many were ruined.

At Leo's death, the Venetian ambassador Gradenigo estimated the number of the Church's paying offices at 2,150, with a capital value of approximately 3,000,000 ducats and a yearly income of 328,000 ducats.

Patron of learning

Leo X raised the Church to a high rank as the friend of whatever seemed to extend knowledge or to refine and embellish life. He made the capital ofChristendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

, Rome, a center of European culture

The culture of Europe is rooted in its art, architecture, film, different types of music, economics, literature, and philosophy. European culture is largely rooted in what is often referred to as its "common cultural heritage".

Definit ...

. While yet a cardinal, he had restored the church of Santa Maria in Domnica after Raphael's designs; and as pope he had San Giovanni dei Fiorentini

The Basilica of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini ("Saint John of the Florentines") is a minor basilica and a titular church in the Ponte ''rione'' of Rome, Italy.

Dedicated to St. John the Baptist, the protector of Florence, the new church for the ...

, on the Via Giulia, built, after designs by Jacopo Sansovino and pressed forward the work on St Peter's Basilica and the Vatican under Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, better known as Raphael (; or ; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form, ease of composition, and visual ...

and Agostino Chigi. Leo's constitution of 5 November 1513 reformed the Roman university, which had been neglected by Julius II. He restored all its faculties, gave larger salaries to the professors, and summoned distinguished teachers from afar; and, although it never attained to the importance of Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

or Bologna, it nevertheless possessed in 1514 a faculty (with a good reputation) of eighty-eight professors.

Leo called Janus Lascaris to Rome to give instruction in Greek, and established a Greek printing-press from which the first Greek book printed at Rome appeared in 1515. He made Raphael custodian of the classical antiquities of Rome and the vicinity, the ancient monuments of which formed the subject of a famous letter from Raphael to the pope in 1519. The distinguished Latinists Pietro Bembo and

Leo called Janus Lascaris to Rome to give instruction in Greek, and established a Greek printing-press from which the first Greek book printed at Rome appeared in 1515. He made Raphael custodian of the classical antiquities of Rome and the vicinity, the ancient monuments of which formed the subject of a famous letter from Raphael to the pope in 1519. The distinguished Latinists Pietro Bembo and Jacopo Sadoleto

Jacopo Sadoleto (July 12, 1477 – October 18, 1547) was an Italian Roman Catholic cardinal and counterreformer noted for his correspondence with and opposition to John Calvin.

Life

He was born at Modena in 1477, the son of a noted jurist, he ...

were papal secretaries, as well as the famous poet Bernardo Accolti

Bernardo Accolti (September 11, 1465March 1, 1536) was an Italian poet.

He was born at Arezzo, the son of Benedetto Accolti.

Known in his own day as ''l'Unico Aretino'', he acquired great fame as a reciter of impromptu verse. He was listened to ...

. Other poets, such as Marco Girolamo Vida, Gian Giorgio Trissino and Bibbiena, writers of ''novelle'' like Matteo Bandello, and a hundred other ''literati'' of the time were bishops, or papal scriptors or abbreviators, or in other papal employ.

Statesman

Several minor events of Leo's pontificate are worthy of mention. He was particularly friendly with KingManuel I of Portugal

Manuel I (; 31 May 146913 December 1521), known as the Fortunate ( pt, O Venturoso), was King of Portugal from 1495 to 1521. A member of the House of Aviz, Manuel was Duke of Beja and Viseu prior to succeeding his cousin, John II of Portuga ...

as a result of the latter's missionary enterprises in Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

. Pope Leo X was granted a large embassy from the Portuguese king furnished with goods from Manuel's colonies. His concordat with Florence (1516) guaranteed the free election of the clergy in that city.

His constitution of 1 March 1519 condemned the King of Spain's claim to refuse the publication of papal bulls. He maintained close relations with Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

because of the Turkish advance and the Polish contest with the Teutonic Knights. His bull of July 1519, which regulated the discipline of the Polish Church, was later transformed into a concordat by Clement VII.

Leo showed special favours to the Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

and permitted them to erect a Hebrew printing

Printing is a process for mass reproducing text and images using a master form or template. The earliest non-paper products involving printing include cylinder seals and objects such as the Cyrus Cylinder and the Cylinders of Nabonidus. The ...

-press at Rome. Under Daniel Bomberg, that press produced manuscripts of the Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the ce ...

and Mikraot Gedolot with Leo's approval and protection.

He approved the formation of the Oratory of Divine Love, a group of pious men at Rome which later became the Theatine Order

The Theatines officially named the Congregation of Clerics Regular ( la, Ordo Clericorum Regularium), abreviated CR, is a Catholic order of clerics regular of Pontifical Right for men founded by Archbishop Gian Pietro Carafa in Sept. 14, 1524. I ...

, and he canonized Francis of Paola.Flesch, Marie. "“That spelling tho”: A Sociolinguistic Study of the Nonstandard Form of Though in a Corpus of Reddit Comments." ''of the 6th Conference on Computer-Mediated Communication (CMC) and Social Media Corpora (CMC-corpora 2018)''.

See also

* Cardinals created by Leo X *Italian Wars

The Italian Wars, also known as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a series of conflicts covering the period 1494 to 1559, fought mostly in the Italian peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and the Mediterranean Sea. The pr ...

* List of sexually active popes

*List of popes from the Medici family

The list of popes from the Medici family includes four men from the late-15th century through the early-17th century. The House of Medici first attained wealth and political power in Florence in the 13th century through its success in commerce an ...

Notes

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * (English translation) * * * * *Further reading

*Luther Martin. ''Luther's Correspondence and Other Contemporary Letters,'' 2 vols., tr. and ed. by Preserved Smith, Charles Michael Jacobs, The Lutheran Publication Society, Philadelphia, Pa. 1913, 1918vol.I (1507–1521)

an

vol.2 (1521–1530)

from

Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google Inc. that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical ...

. Reprint of Vol.1, Wipf & Stock Publishers (March 2006).

*Zophy, Jonathan W. ''A Short History of Renaissance and Reformation: Europe Dances over Fire and Water''. 1996. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2003.

External links

*Vita de Leonis X

life in Latin by

Paulus Jovius

Paolo Giovio (also spelled ''Paulo Jovio''; Latin: ''Paulus Jovius''; 19 April 1483 – 11 December 1552) was an Italian physician, historian, biographer, and prelate.

Early life

Little is known about Giovio's youth. He was a native of Co ...

Henry VIII to Pope Leo X. 21 May 1521

._Rome,_8_July_1520.html" ;"title="Elector of Saxony">Leo X to Frederic, Elector_of_Saxony">Leo_X_to_Frederic,_Elector_of_Saxony

._Rome,_8_July_1520br>

{{DEFAULTSORT:Leo_10 Pope_Leo_X.html" ;"title="Elector of Saxony

. Rome, 8 July 1520">Elector of Saxony">Leo X to Frederic, Elector of Saxony

. Rome, 8 July 1520br>Paradoxplace Medici Popes' Page

{{DEFAULTSORT:Leo 10 Pope Leo X"> Cardinal-nephews Italian popes Clergy from Florence House of Medici 1475 births 1521 deaths Renaissance Papacy Burials at Santa Maria sopra Minerva Popes Simony 16th-century popes Italian art patrons Deaths from pneumonia in Lazio