Pope Honorius II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pope Honorius II (9 February 1060 – 13 February 1130), born Lamberto Scannabecchi,Levillain, pg. 731 was head of the

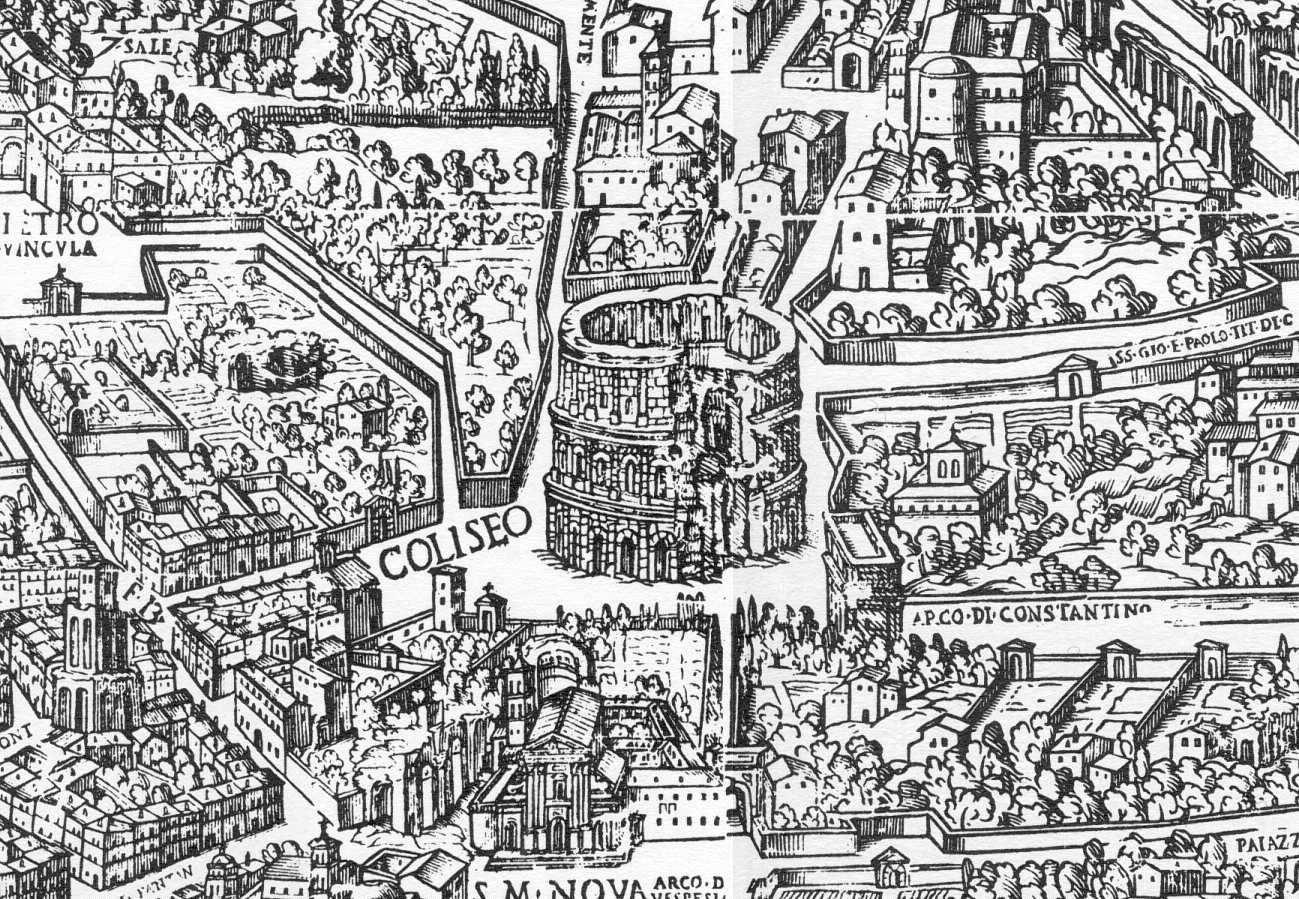

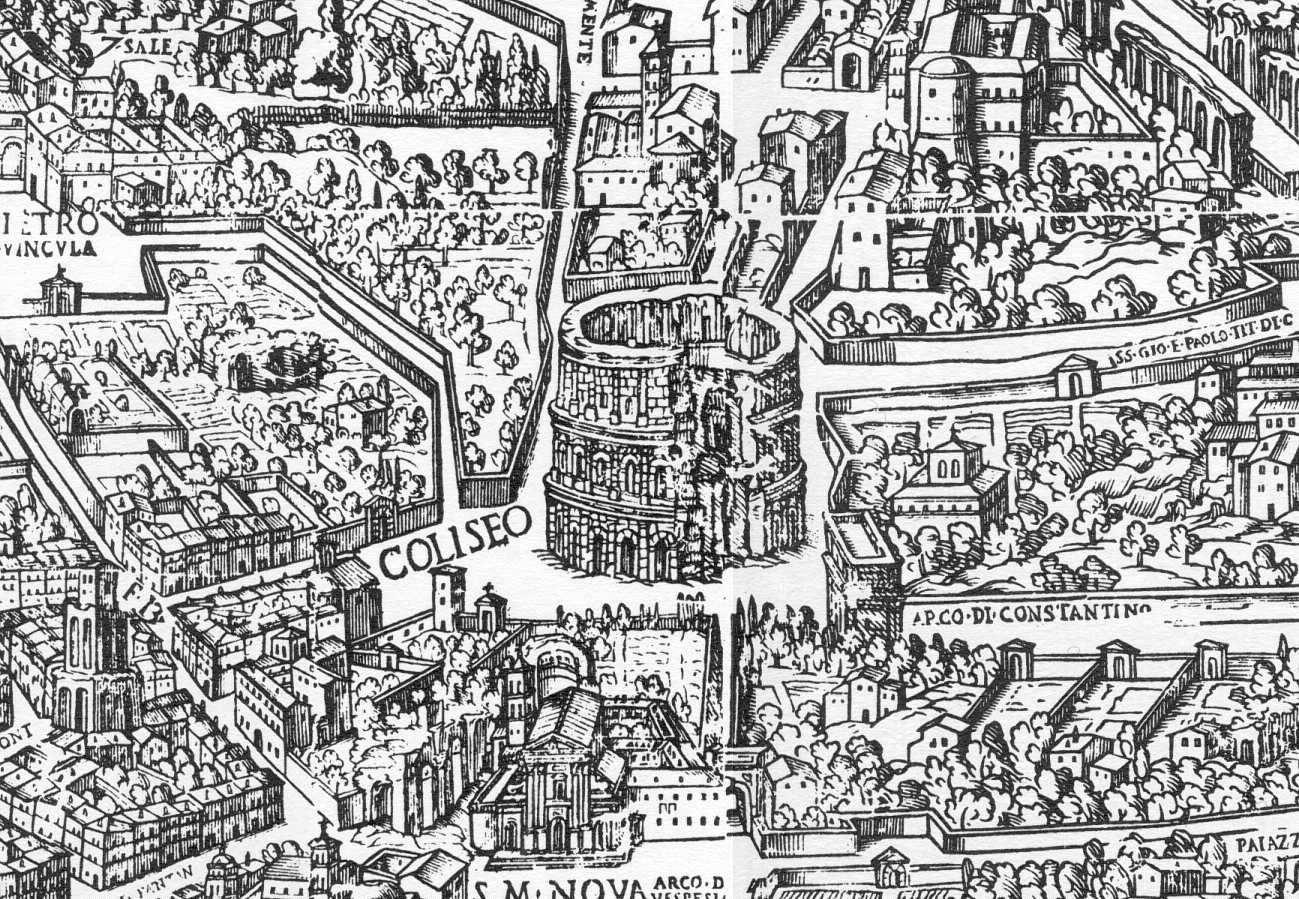

By 1124, there were two great factions dominating local politics in Rome: the Frangipani family, which controlled the region around the fortified

By 1124, there were two great factions dominating local politics in Rome: the Frangipani family, which controlled the region around the fortified

The death of Emperor Henry V on 23 May 1125 put an end to these squabbles, but soon Honorius was involved in a new power struggle in the

The death of Emperor Henry V on 23 May 1125 put an end to these squabbles, but soon Honorius was involved in a new power struggle in the

Matters to the south of Monte Cassino soon occupied Honorius's attention. In July 1127, William II, Duke of Apulia, died childless, and almost immediately his cousin King Roger II of Sicily sailed to the mainland to occupy the duchies of Apulia and Calabria. Roger claimed that William had nominated him his heir, while Honorius stated that William had left his territory to the

Matters to the south of Monte Cassino soon occupied Honorius's attention. In July 1127, William II, Duke of Apulia, died childless, and almost immediately his cousin King Roger II of Sicily sailed to the mainland to occupy the duchies of Apulia and Calabria. Roger claimed that William had nominated him his heir, while Honorius stated that William had left his territory to the

In 1119, a new religious order had been established by some French noblemen. Called the Knights Templar, they were to protect Christian pilgrims entering the Holy Land and to defend the conquests of the

In 1119, a new religious order had been established by some French noblemen. Called the Knights Templar, they were to protect Christian pilgrims entering the Holy Land and to defend the conquests of the

Honorius II * * Gregorovius, Ferdinand (1896) ''History of Rome in the Middle Ages'', Volume IV. 2 second edition, revised (London: George Bell). * Hüls, Rudolf (1977) ''Kardinäle, Klerus und Kirchen Roms: 1049–1130 ''(Tübingen) ibliothek des Deutschen Historischen Instituts in Rom, Band 48 * Levillain, Philippe (2002) ''The Papacy: An Encyclopedia, Vol II: Gaius-Proxies'', Routledge * * Pandulphus Pisanus (1723) "Vita Calisti Papae II," "Vita Honorii II," Ludovico Antonio Muratori (editor), ''Rerum Italicarum Scriptores'' III. 1 (Milan), pp. 418–419; 421–422. * Stroll, Mary (1987) ''The Jewish Pope'' (New York: Brill 1987). * Stroll, Mary (2005) ''Calixtus II'' (New York: Brill 2005). * Thomas, P. C. (2007) ''A Compact History of the Popes'', St Pauls BYB

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and ruler of the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

from 21 December 1124 to his death in 1130.

Although from a humble background, his obvious intellect and outstanding abilities saw him promoted up through the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Attached to the Frangipani family of Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, his election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

as pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

was contested by a rival candidate, Celestine II

Pope Celestine II ( la, Caelestinus II; died 8 March 1144), born Guido di Castello,Thomas, pg. 91 was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 26 September 1143 to his death in 1144.

Early life

Guido di Castello, possibly ...

, and force was used to guarantee his election.

Honorius's pontificate was concerned with ensuring that the privileges the Roman Catholic Church had obtained through the Concordat of Worms were preserved and, if possible, extended. He was the first pope to confirm the election of the Holy Roman emperor. Distrustful of the traditional Benedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, foun ...

order, he favoured new monastic orders, such as the Augustinians and the Cistercians, and sought to exercise more control over the larger monastic centres of Monte Cassino

Monte Cassino (today usually spelled Montecassino) is a rocky hill about southeast of Rome, in the Latin Valley, Italy, west of Cassino and at an elevation of . Site of the Roman town of Casinum, it is widely known for its abbey, the first ho ...

and Cluny Abbey. He also approved the new military order of the Knights Templar in 1128.

Honorius II failed to prevent Roger II of Sicily from extending his power in southern Italy and was unable to stop Louis VI of France from interfering in the affairs of the French church. Like his predecessors, he managed the wide-ranging affairs of the church through Papal Legates. With his death in 1130, the Church was again thrown into confusion with the election of two rival popes, Innocent II

Pope Innocent II ( la, Innocentius II; died 24 September 1143), born Gregorio Papareschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 February 1130 to his death in 1143. His election as pope was controversial and the fi ...

and the antipope Anacletus II.

Early life

Lamberto was of simple rural origins, hailing from Fiagnano in theCasalfiumanese

Casalfiumanese ( rgn, Casêl Fiumanés) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Bologna in the Italian region Emilia-Romagna, located about southeast of Bologna.

Casalfiumanese borders the following municipalities: Borgo Tossi ...

commune, near Imola

Imola (; rgn, Jômla or ) is a city and ''comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Bologna, located on the river Santerno, in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy. The city is traditionally considered the western entrance to the historical ...

in present-day Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. Entering into an ecclesiastical career, he soon became archdeacon of Bologna

Bologna (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language, Emilian, Bulåggna ; lat, Bononia) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy with about 400,000 inhabitants and 1 ...

, where his abilities eventually saw him attract the attention of Pope Urban II,Mann, pg. 234. who presumably appointed him cardinal priest

A cardinal ( la, Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae cardinalis, literally 'cardinal of the Holy Roman Church') is a senior member of the clergy of the Catholic Church. Cardinals are created by the ruling pope and typically hold the title for life. Col ...

of an unknown church, in c. 1099, though S. Prassede has been discussed. His successor, Pope Paschal II

Pope Paschal II ( la, Paschalis II; 1050 1055 – 21 January 1118), born Ranierius, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 August 1099 to his death in 1118. A monk of the Abbey of Cluny, he was cre ...

, made Lamberto a Canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western ca ...

of the Lateran

250px, Basilica and Palace - side view

Lateran and Laterano are the shared names of several buildings in Rome. The properties were once owned by the Lateranus family of the Roman Empire. The Laterani lost their properties to Emperor Constantine ...

Thomas, pg. 90. before elevating him to the position of cardinal bishop

A cardinal ( la, Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae cardinalis, literally 'cardinal of the Holy Roman Church') is a senior member of the clergy of the Catholic Church. Cardinals are created by the ruling pope and typically hold the title for life. C ...

of Ostia in 1117. Lamberto was one of the cardinals who accompanied Pope Gelasius II into exile in 1118–19 and was at his bedside when Gelasius died.

With Gelasius's death at Cluny on 28 January 1119, Cardinal Lamberto and Cardinal Cono (Bishop of Palestrina) conducted the election of a new pope according to the canons. Cardinal Lamberto carried out the coronation of Guy de Bourgogne at Vienne on 9 February 1119, and became a close advisor of Pope Callixtus II. Accompanying Callixtus throughout France, he assisted Callixtus in his initial dealings with Holy Roman Emperor Henry V. As a well-known opponent of the emperor's right to select bishops in his territories (the Investiture Controversy

The Investiture Controversy, also called Investiture Contest ( German: ''Investiturstreit''; ), was a conflict between the Church and the state in medieval Europe over the ability to choose and install bishops ( investiture) and abbots of mona ...

), Lamberto was a natural choice for papal legate. He was sent in 1119 to deal with Henry V and delegated with powers to come to an understanding concerning the right of investiture.

Forceful and determined, he summoned the bishops of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

to attend an assembly at Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

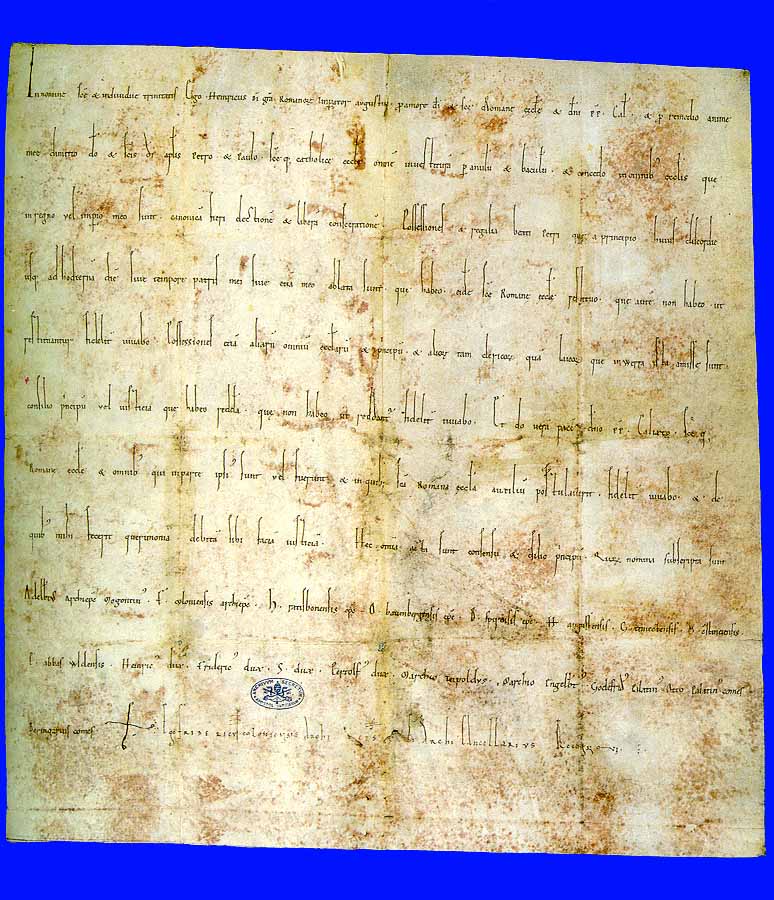

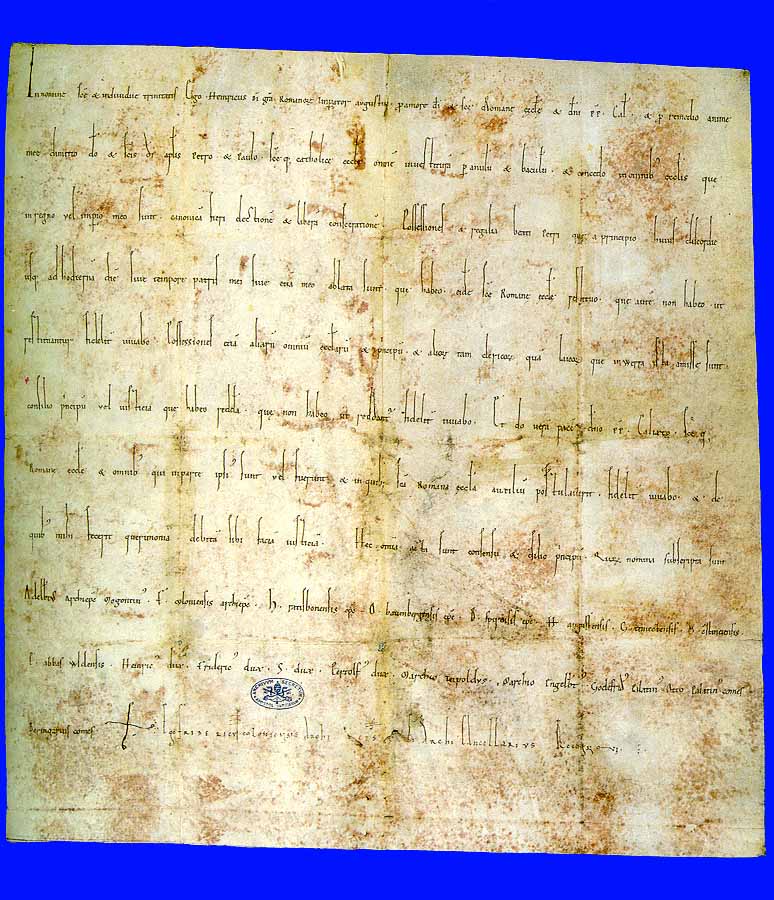

on 8 September 1122. He expected absolute obedience, so much so that it took the mediation of Archbishop Adalbert of Mainz to prevent the suspension of Saint Otto of Bamberg for non-attendance.Mann, pg. 235 The struggle came to a conclusion with the Concordat of Worms in 1122 and the "''Pactum Calixtinum''" that was almost entirely due to Lamberto's efforts was effected on 23 September 1123.

Pontificate

Conclave of 1124

Pressures building within theCuria

Curia (Latin plural curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally likely had wider powers, they came ...

, together with ongoing conflicts among the Roman nobility, would erupt after the death of Callixtus II in 1124.Levillain, pg. 732 The pontificates of Urban II and Paschal II saw an expansion in the College of Cardinals

The College of Cardinals, or more formally the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. its current membership is , of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Cardinals are app ...

of Italian clerics that strengthened the local Roman influence. These cardinals were reluctant to meet with the batch of cardinals recently promoted by Callixtus II, who were mainly French or Burgundian. As far as the older cardinals were concerned, these newer cardinals were dangerous innovators, and they were determined to resist their increasing influence. The northern cardinals, led by Cardinal Aymeric de Bourgogne (the Papal Chancellor), were equally determined to ensure that the elected pope would be one of their candidates. Both groups looked towards the great Roman families for support.

By 1124, there were two great factions dominating local politics in Rome: the Frangipani family, which controlled the region around the fortified

By 1124, there were two great factions dominating local politics in Rome: the Frangipani family, which controlled the region around the fortified Colosseum

The Colosseum ( ; it, Colosseo ) is an oval amphitheatre in the centre of the city of Rome, Italy, just east of the Roman Forum. It is the largest ancient amphitheatre ever built, and is still the largest standing amphitheatre in the world t ...

and supported the northern cardinals, and the Pierleoni family The family of the Pierleoni, meaning "sons of Peter Leo", was a great Roman patrician clan of the Middle Ages, headquartered in a tower house in the quarter of Trastevere that was home to a larger number of Roman Jews. The heads of the family ofte ...

, which controlled the Tiber Island

The Tiber Island ( it, Isola Tiberina, Latin: ''Insula Tiberina'') is the only river island in the part of the Tiber which runs through Rome. Tiber Island is located in the southern bend of the Tiber.

The island is boat-shaped, approximately ...

and the fortress of the Theatre of Marcellus

The Theatre of Marcellus ( la, Theatrum Marcelli, it, Teatro di Marcello) is an ancient open-air theatre in Rome, Italy, built in the closing years of the Roman Republic. At the theatre, locals and visitors alike were able to watch performances o ...

and supported the Italian cardinals.Mann, pg. 231 With Callixtus II's death on 13 December 1124, both families agreed that the election of the next pope should be in three days time, in accordance with the church canons. The Frangipani, led by Leo Frangipani, pushed for the delay in order that they could promote their preferred candidate, Lamberto, but the people were eager to see Saxo de Anagni, the Cardinal-Priest of San Stefano in Celiomonte elected as the next pope. Leo, eager to ensure a valid election, approached key members of every Cardinal's entourage, promising each one that he would support their master when the voting for the election was underway.Mann, pg. 232

On 16 December, all the Cardinals, including Lamberto, assembled in the chapel of the monastery of St. Pancratius attached to the south of the Lateran basilica. There, at the suggestion of Jonathas Jonathas is a given name. Notable people with the name include:

*Jonathas de Jesus (born 1989), Brazilian footballer

*Jonathas Granville (1785–1839), Haitian educator, legal expert, soldier, and diplomat

;Other

*''David et Jonathas'', French ope ...

, the cardinal-deacon of Santi Cosma e Damiano

The basilica of Santi Cosma e Damiano is a titular church in Rome, Italy. The lower portion of the building is accessible through the Roman Forum and incorporates original Roman buildings, but the entrance to the upper level is outside the Foru ...

, who was a partisan of the Pierleoni family, the Cardinals unanimously elected as Pope the Cardinal-Priest of Sant'Anastasia, Theobaldo Boccapecci, who took the name Celestine II

Pope Celestine II ( la, Caelestinus II; died 8 March 1144), born Guido di Castello,Thomas, pg. 91 was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 26 September 1143 to his death in 1144.

Early life

Guido di Castello, possibly ...

.Thomas, pg. 90 He had only just put on the red mantle and the ''Te Deum

The "Te Deum" (, ; from its incipit, , ) is a Latin Christian hymn traditionally ascribed to AD 387 authorship, but with antecedents that place it much earlier. It is central to the Ambrosian hymnal, which spread throughout the Latin Ch ...

'' was being sung when an armed party of Frangipani supporters (in a move pre-arranged with Cardinal Aymeric) burst in, attacked the newly enthroned Celestine, who was wounded, and acclaimed Lamberto as Pope. Since Celestine had not been formally consecrated pope, the wounded candidate declared himself willing to resign, but the Pierleoni family and their supporters refused to accept Lamberto, who in the confusion had been proclaimed Pope under the name Honorius II.Mann, pg. 233

Rome descended into factional infighting, while Cardinal Aymeric and Leo Frangipani attempted to win over the resistance of Urban, the City Prefect, and the Pierleoni family with bribes and extravagant promises. Eventually, Celestine's supporters abandoned him, leaving Honorius the only contender for the papal throne. Honorius, unwilling to accept the throne in such a manner, resigned his position before all of the assembled Cardinals, but was immediately and unanimously re-elected and consecrated on 21 December 1124.

Papacy

Relations with the Holy Roman Empire

Honorius immediately came into conflict with Emperor Henry V over imperial claims in Italy. In 1116, Henry had crossed theAlps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Swi ...

to lay claim to the Italian territories of Matilda of Tuscany, which she had supposedly left to the papacy on her death.Mann, pg. 238 Henry had immediately begun appointing imperial vicars throughout the newly acquired province over the objections of both the Tuscan cities and the papacy. To maintain papal claims to Tuscany, Honorius appointed Albert, a papal marquis, to rule in the pope's name in opposition to the imperial Margrave of Tuscany

The rulers of Tuscany varied over time, sometimes being margraves, the rulers of handfuls of border counties and sometimes the heads of the most important family of the region.

Margraves of Tuscany, 812–1197 House of Boniface

:These were origin ...

, Conrad von Scheiern. In addition, Henry V made very little effort to implement the terms of the Concordant of Worms, to Honorius II's irritation. Local churches were forced to appeal to Rome to obtain restitution from the imperial bishops who had taken advantage of the Investiture Controversy to obtain property for their own benefit, as the Emperor turned a blind eye.

The death of Emperor Henry V on 23 May 1125 put an end to these squabbles, but soon Honorius was involved in a new power struggle in the

The death of Emperor Henry V on 23 May 1125 put an end to these squabbles, but soon Honorius was involved in a new power struggle in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

. Henry died childless and had nominated his nephew Frederick Hohenstaufen, Duke of Swabia, to succeed him as King of the Romans and Holy Roman Emperor.Mann, pg. 240 Of the German princes, the ecclesiastical faction was against any expansion of Hohenstaufen power, and they were determined to ensure that Frederick would not succeed Henry. Led by Archbishop Adalbert of Mainz, the archchancellor

An archchancellor ( la, archicancellarius, german: Erzkanzler) or chief chancellor was a title given to the highest dignitary of the Holy Roman Empire, and also used occasionally during the Middle Ages to denote an official who supervised the wo ...

of the empire, and under the watchful gaze of two papal legates, Cardinals Gherardo and Romano, the clerical and lay nobles of the empire elected Lothair of Supplinburg, Duke of Saxony.Mann, pg. 241 At Lothair's request, Cardinal Gherardo and two bishops then sent word to Rome to obtain Honorius's confirmation of the election, which he granted. This was a coup for Honorius, as such a confirmation had never occurred before, and around July 1126 Honorius invited Lothair to Rome to obtain the imperial title. Lothair was keen to keep Honorius on his side, keeping to the terms of the Concordat of Worms by not attending episcopal elections, agreeing that the investiture should only occur after the bishop's consecration, and that the oath of homage be replaced with an oath of fidelity.

Lothair was unable to visit Rome immediately as Germany was rocked by the rebellion of the Hohenstaufen brothers, with Conrad Hohenstaufen elected anti-king in December 1127, followed by his descent into Italy and his crowning as King of Italy

King of Italy ( it, links=no, Re d'Italia; la, links=no, Rex Italiae) was the title given to the ruler of the Kingdom of Italy after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. The first to take the title was Odoacer, a barbarian military leader ...

at Monza on 29 July 1128. The German bishops, again led by Adalbert of Mainz, excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

Conrad, an act that was confirmed by Honorius in a synod held in Rome at Easter

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the '' Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

(22 April 1128). Honorius also sent Cardinal John of Crema to Pisa to hold another synod that excommunicated Archbishop Anselm of Milan, who had crowned Conrad king. Conrad found little help in Italy and with Honorius's support, Lothair was able to keep his throne.

One of the key ecclesiastical advisors of Lothair III was Saint Norbert of Xanten

Norbert of Xanten, O. Praem (c. 1075 – 6 June 1134) (Xanten-Magdeburg), also known as Norbert Gennep, was a bishop of the Catholic Church, founder of the Premonstratensian order of canons regular, and is venerated as a saint. Norbert was can ...

, who travelled to Rome in early 1126Mann, pg. 244 to seek the formal sanction from Honorius to establish a new monastic order, the Premonstratensian Order

The Order of Canons Regular of Prémontré (), also known as the Premonstratensians, the Norbertines and, in Britain and Ireland, as the White Canons (from the colour of their habit), is a religious order of canons regular of the Catholic Church ...

(also known as the Norbertines), which Honorius agreed to do.

Concerns in Campania

One of Honorius's first tasks in southern Italy was to deal with the barons in theCampania

(man), it, Campana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demog ...

who were molesting farmers and travellers at will with their armed bands.Mann, pg. 246 In 1125, papal force brought to heel the lords of Ceccano

Ceccano is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Frosinone, Lazio, central Italy, in the Latin Valley.

History

The town had its origins as an ancient Volscian citadel that surrendered to the Romans in 330 BC (424 Ab Urbe Condita).''The History ...

. Papal armies took possession of various towns, including Maenza, Roccasecca

Roccasecca is a town and ''comune'' in the Province of Frosinone, in the Lazio region of central Italy. It is the birthplace of Thomas Aquinas.

History

The history of Roccasecca is tightly bound to its strategic position, a "dry '' rocca''" at ...

and Trevi nel Lazio

Trevi nel Lazio is a town and ''comune'' (municipality) in the province of Frosinone in the Italian region of Lazio in the upper valley of the Aniene river.

It is by road northeast of Fiuggi and by road southeast of Subiaco, the nearest large ...

. In 1128, Honorius's forces successfully captured the town of Segni

Segni (, ) is an Italian town and ''comune'' located in Lazio. The city is situated on a hilltop in the Lepini Mountains, and overlooks the valley of the Sacco River.

History

Early history

According to ancient Roman sources, Lucius Tarquiniu ...

, which was also held by a local baron who died during its capture.Mann, pg. 252 Honorius, however, was most concerned about the former papal stronghold at Fumone, which the nobles, who held it in the pope's name, had decided to keep possession of. The town fell in July 1125 after a siege of ten weeks. When Honorius took possession of Fumone, he returned it, after taking safeguards, to its rebellious custodians and ordered that the Antipope Gregory VIII

Gregory VIII (died 1137), born Mauritius Burdinus (''Maurice Bourdin''), was antipope from 10 March 1118 until 22 April 1121.

Biography

He was born in the Limousin, part of Occitania, France. He was educated at Cluny, at Limoges, and in Castil ...

be transferred there from his previous lodgings at Monte Cassino

Monte Cassino (today usually spelled Montecassino) is a rocky hill about southeast of Rome, in the Latin Valley, Italy, west of Cassino and at an elevation of . Site of the Roman town of Casinum, it is widely known for its abbey, the first ho ...

. With that, Honorius turned his attention to the powerful and independent-minded abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The ...

of Monte Cassino, Oderisio di Sangro.

Honorius had a long-standing dislike of Oderisio going back to the time when Honorius was cardinal-bishop of Ostia.Mann, pg. 248 Honorius had asked for permission from the abbot to allow him and his entourage permission to stay in the church of Santa Maria in Pallara, which was a traditional privilege belonging to the bishops of Ostia. Oderisio refused, and Honorius never forgot the insult. These bad feelings were compounded in 1125, when Oderisio refused a request from Pope Honorius for some financial assistance after he had been enthroned. Oderisio also mocked Honorius's peasant background behind his back.Mann, pg. 249

Using reports that the abbot had been lining his own pockets rather than spending it on his monastery, Honorius publicly denounced Oderisio, calling him a soldier and a thief, not a monk. When Atenulf, count of Aquino, brought accusations that Oderisio was aiming for the papacy, Honorius summoned Oderisio to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

to answer the charges. Three times Oderisio refused to answer the summons and so during Lent

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring temptation by Satan, according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke ...

of 1126, Honorius deposed the abbot. Oderisio refused to accept the deposition and continued to act as abbot, forcing Honorius to excommunicate him. Oderisio fortified the monastery, as the people of the town of Cassino forcibly entered the monastery, and after an armed struggle forced the monks to declare Oderisio deposed and to elect another abbot in his place. The monks elected Niccolo, the dean of the monastery.

Determined to bring the Benedictines to heel, Honorius insisted that the election of Niccolo was uncanonical, and demanded that Seniorectus, the provost of the monastery at Capua

Capua ( , ) is a city and ''comune'' in the province of Caserta, in the region of Campania, southern Italy, situated north of Naples, on the northeastern edge of the Campanian plain.

History

Ancient era

The name of Capua comes from the Etrus ...

, be elected as abbot, to the fury of the Monte Cassino monks.Mann, pg. 250 In the meantime, open warfare was being waged between the supporters of Oderisio and Niccolo. Eventually, however, Honorius was able to secure not only the resignation of Oderisio, but he also excommunicated Niccolo for good measure. He reassured the monks of his intentions, and in September 1127, he personally installed Seniorectus as abbot.Mann, pg. 251 Honorius also insisted that the monks take an oath of fidelity to the papacy, but they strenuously objected.

Conflict with Roger II of Sicily

Matters to the south of Monte Cassino soon occupied Honorius's attention. In July 1127, William II, Duke of Apulia, died childless, and almost immediately his cousin King Roger II of Sicily sailed to the mainland to occupy the duchies of Apulia and Calabria. Roger claimed that William had nominated him his heir, while Honorius stated that William had left his territory to the

Matters to the south of Monte Cassino soon occupied Honorius's attention. In July 1127, William II, Duke of Apulia, died childless, and almost immediately his cousin King Roger II of Sicily sailed to the mainland to occupy the duchies of Apulia and Calabria. Roger claimed that William had nominated him his heir, while Honorius stated that William had left his territory to the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

.Mann, pg. 253 Honorius had just suffered a defeat at the hands of a local baron at Arpino

Arpino (Southern Latian dialect: ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the province of Frosinone, in the Latin Valley, region of Lazio in central Italy, about 100 km SE of Rome. Its Roman name was Arpinum. The town produced two consuls of the R ...

in 1127 when Honorius received word that Roger had landed in Italy. He rushed to Benevento to prevent the local Normans from reaching an agreement with Roger. Roger in the meantime had rapidly overrun the duchy of Apulia and had sent Honorius lavish gifts, asking the Pope to recognise him as the new duke and promising to hand over Troia and Montefusco

Montefusco is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Avellino, Campania, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Medite ...

in exchange. Honorius, fearing the expansion of Norman power to the south under one dominating ruler, threatened to excommunicate Roger if he persisted. In the meantime, many of the local Norman nobles, fearful of Roger's power, allied themselves with Honorius, as Honorius formally excommunicated Roger in November 1127.Mann, pg. 254 Roger left his armies threatening Benevento, while he returned to Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

for reinforcements. Honorius in the meantime entered into an alliance with the new Prince of Capua, Robert II. On 30 December 1127, Honorius preached a crusade against Roger II after having anointed Robert as Prince of Capua.

Roger returned in May 1128 and continued to harass papal strongholds while avoiding any direct confrontation with Honorius's forces. In July 1128, the two armies came in contact with each other on the banks of the Bradano

The Bradano is a river in the Basilicata and Apulia regions of southern Italy. Its source is Lago Pesole (which is near Forenza and Filiano) in the province of Potenza. The river flows southeast near Monte Torretta, Acerenza, and Oppido Lucano. ...

, but Roger refused to engage, believing that the papal armies would soon fall apart, and soon enough some of the Pope's allies began deserting to Roger.Mann, pg. 255 Trying to salvage something of the situation, Honorius sent his trusted advisor Cardinal Aymeric together with Cencio II Frangipane

Cencius II or Cencio II Frangipane was the son of either of Cencio I or of John, a brother of one Leo. He was the principal representative of the Frangipani family of Rome in the early twelfth century.

One night in 1118, he interrupted the Coll ...

to negotiate with Roger secretly. Honorius agreed to invest Roger with the duchy of Apulia in exchange for an oath of faith and homage by Roger.

Honorius travelled to Benevento, and after safeguarding the interests of Robert of Capua, he met Roger on the Pons Major, the bridge which crosses the Sabbato river near Benevento, on 22 August 1128. There, he formally invested Roger with the duchy of Apulia and both agreed to a peace between the Kingdom of Sicily and the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

. Unfortunately, Honorius had just returned to Rome when he was informed that the nobles of Benevento had overthrown and killed the rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

(or papal governor) of the city and established a Commune.Mann, pg. 256 Furious, he declared he would wreak a terrible vengeance on the city, whereupon the residents asked Honorius for forgiveness and to send another governor. Honorius sent Cardinal Gherardo as the new rector, and in 1129 visited the city again, asking that the city allow the return of those they had banished during the formation of the Commune. They refused, and Honorius asked Roger II of Sicily to punish the city in May 1130, but Honorius died before action was taken.

Intervention in France

Aside from the Benedictines at Monte Cassino, Honorius was also determined to deal with the monks at Cluny Abbey under their ambitious and worldlyabbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. The ...

, Pons of Melgueil

Pons of Melgueil (''c''. 1075 – 1126) was the seventh Abbot of Cluny from 1109 to 1122.

Pons was the second child of Peter I of Melgueil and Almodis of Toulouse. He was descended from a noble lineage of Languedoc which had long supported the ...

. He had just returned from the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

after being forced out by his monks in 1122.Mann, pg. 260 In 1125, accompanied by an armed following, Pons took possession of Cluny Abbey, melted down the treasures stored in the monastery, and paid his followers, who continued to terrorise the monks and the villages dependent upon the abbey.

Honorius, on hearing news of the disorders at Cluny, sent a legate to investigate with orders to excommunicate and denounce Pons and order him to present himself before Honorius. Pons eventually obeyed the summons, and was deposed by Honorius in 1126 before being imprisoned in the Septizodium

The Septizodium (also called ''Septizonium'' or ''Septicodium'') was a building in ancient Rome. It was built in 203 AD by Emperor Septimius Severus. The origin of the name "Septizodium" is from ''Septisolium'', from the Latin for temple of seve ...

, where he soon died.Mann, pg. 261 Honorius personally reinvested Peter the Venerable as Abbot of Cluny.

Honorius soon became involved in the quarrel between King Louis VI of France and the French bishops. Stephen of Senlis, the Bishop of Paris, had been heavily influenced by the reforming zeal of Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, O. Cist. ( la, Bernardus Claraevallensis; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templars, and a major leader in the reformation of the Benedictine Order throug ...

, and actively sought to remove royal influence in the French church.Mann, pg. 262 Louis confiscated Stephen's wealth and began harassing him so that he would cease his reforming activities. At the same time, Louis also had in his sights Henri Sanglier, the Archbishop of Sens, who had also joined the reformers.Mann, pg. 264 Charging Henri with simony, Louis attempted to remove another threat from within the French church. Bernard of Clairvaux wrote to Honorius asking him to intervene on behalf of both men and support church independence over the claims of royal jurisdiction and interference.Mann, pg. 265

Royal pressure was also brought to bear on Hildebert of Lavardin

Hildebert (c. 105518 December 1133) was a French ecclesiastic, hagiographer and theologian. From 1096–97 he was bishop of Le Mans, then from 1125 until his death archbishop of Tours. Sometimes called Hildebert of Lavardin, his name may also be s ...

, whom Honorius had transferred from the see of Le Mans to become the Archbishop of Tours

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Tours (Latin: ''Archidioecesis Turonensis''; French: ''Archidiocèse de Tours'') is an archdiocese of the Latin Rite of the Roman Catholic Church in France. The archdiocese has roots that go back to the 3rd centu ...

in 1125. In 1126, Louis insisted on filling episcopal vacancies in the See of Tours

Tours ( , ) is one of the largest cities in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the prefecture of the department of Indre-et-Loire. The commune of Tours had 136,463 inhabitants as of 2018 while the population of the whole metro ...

with his own candidates over Hildebert's objections. Hildebert also complained to Honorius about the constant appeals to Rome whenever he made a ruling.

In response to the king's actions, the French bishops laid an interdict

In Catholic canon law, an interdict () is an ecclesiastical censure, or ban that prohibits persons, certain active Church individuals or groups from participating in certain rites, or that the rites and services of the church are banished from ...

on the diocese of Paris

The Archdiocese of Paris (Latin: ''Archidioecesis Parisiensis''; French: ''Archidiocèse de Paris'') is a Latin Church ecclesiastical jurisdiction or archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. It is one of twenty-three archdioceses in Franc ...

, causing Louis to write to Honorius, who suspended the interdict in 1129.Mann, pg. 263 Although this incurred the wrath of Bernard of Clairvaux, who wrote to Honorius expressing his disgust, Honorius pressured Stephen of Senlis to become reconciled with King Louis in 1130. Henri Sanglier, on the other hand, continued in his role of archbishop without further interference from the king. By the end of his pontificate, Honorius had ended the conflict between Louis and his bishops.

In 1127, Honorius confirmed the acts of the Synod of Nantes, presided over by Archbishop Hildebert of Lavardin, which eradicated certain local abuses in Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

. That same year, Honorius helped Conan III, Duke of Brittany

Conan III, also known as Conan of Cornouaille and Conan the Fat ( br, Konan III a Vreizh, and ; c. 1093–1096 – September 17, 1148) was duke of Brittany, from 1112 to his death. He was the son of Alan IV, Duke of Brittany and Ermengarde of An ...

, bring one of his rebellious vassals to heel. He also intervened on behalf of the monks of the Lérins Islands who were constantly harassed by Arab pirates, encouraging a crusade to help defend the monks.

Honorius was also called to intervene in the affairs of Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

, as Fulk of Anjou and King Henry I of England battled for domination. Henry objected to the marriage of Fulk's daughter Sibylla of Anjou

Sibylla of Anjou (–1165) was a countess consort of Flanders as the wife of Thierry, Count of Flanders. She served as the regent of Flanders during the absence of her spouse in 1147-1149.

First marriage

Sybilla was the daughter of Fulk V of Anj ...

to William Clito

William Clito (25 October 110228 July 1128) was a member of the House of Normandy who ruled the County of Flanders from 1127 until his death and unsuccessfully claimed the Duchy of Normandy. As the son of Robert Curthose, the eldest son of William ...

, the son of the duke of Normandy, on the grounds that they were too closely related by blood, being sixth cousins. They refused to divorce, and Honorius was forced to excommunicate Fulk and his son-in-law and to impose an interdict upon their territories.

Relations with England and Spain

In England, the ongoing dispute between the Sees ofCanterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of ...

and York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

over primacy continued unabated. On 5 April 1125, Honorius wrote to Thurstan

:''This page is about Thurstan of Bayeux (1070 – 1140) who became Archbishop of York. Thurstan of Caen became the first Norman Abbot of Glastonbury in circa 1077.''

Thurstan or Turstin of Bayeux ( – 6 February 1140) was a medi ...

, Archbishop of York, advising him that Honorius planned to settle the issue personally.Mann, pg. 285 He sent a legate, Cardinal John of Crema

John of Crema (Giovanni da Crema) (died before 27 January 1137) was an Italian papal legate and cardinal. He was a close supporter of Pope Callistus II.

Cardinal

Giovanni, the son of Olricus and Rathildis, was a native of Crema, a town 17km nort ...

, to deal with the question of primacy, as well as other jurisdictional issues between Canterbury and Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

, and between York, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

. Honorius wrote to the clergy and nobles of England, directing them to treat his legate as if he were Honorius himself.

In Honorius's name, John of Crema convened the Synod of Roxburgh

Roxburgh () is a civil parish and formerly a royal burgh, in the historic county of Roxburghshire in the Scottish Borders, Scotland. It was an important trading burgh in High Medieval to early modern Scotland. In the Middle Ages it had at leas ...

in 1125. In a letter written to King David I of Scotland

David I or Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim ( Modern: ''Daibhidh I mac haoilChaluim''; – 24 May 1153) was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians from 1113 to 1124 and later King of Scotland from 1124 to 1153. The youngest son of Mal ...

, the king was asked to send the bishops of Scotland to the Council, which discussed the claims of the Archbishop of York to have jurisdiction over the church in Scotland. Upholding the claims of York, Honorius was unsuccessful in forcing the Scottish bishops to obey Archbishop Thurstan.Mann, pg. 287

Next, John convened the Synod of Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

in September 1125, which was attended by both the archbishops of Canterbury and York, together with twenty bishops and forty abbots. Although the synod issued rulings on the forbidding of simony and of holding multiple sees at the same time, it did not touch on the vexed question of primacy between Canterbury and York. Instead, John summoned the two prelates

A prelate () is a high-ranking member of the Christian clergy who is an ordinary or who ranks in precedence with ordinaries. The word derives from the Latin , the past participle of , which means 'carry before', 'be set above or over' or 'pref ...

to travel with him to Rome to discuss the matter in person before Honorius.Mann, pg. 291 They arrived in late 1125 and were greeted warmly by Honorius, and they remained in Rome until early 1126. While there, Honorius ruled that the Bishop of St Andrews was to be subject to the Archbishop of York and in the more contentious issue, he attempted to circumvent his way around the problem by declaring that Thurstan was subject to William de Corbeil, not in his role as Archbishop of Canterbury, but as papal legate for England and Scotland.Mann, pg. 292 To emphasise this, Honorius decreed that the Archbishop of Canterbury could not ask for any oath of obedience from the Archbishop of York, and in the matter of honorary distinction, it was the Archbishop of Canterbury in his role as Legate that was the most elevated ecclesiastic in the kingdom.

Urban of Llandaff also travelled to Rome on numerous occasions to meet with Honorius throughout 1128 and 1129, to plead his case that his diocese should not be subject to the see of Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of ...

. Although he obtained numerous privileges for his see and Honorius always spoke encouragingly to him, Honorius avoided having to make a decision that might alienate the powerful archbishops of Canterbury.

In Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, Honorius was deeply suspicious of the ambitions of Diego Gelmírez

Diego Gelmírez or Xelmírez ( la, Didacus Gelmirici; c. 1069 – c. 1140) was the second bishop (from 1100) and first archbishop (from 1120) of the Catholic Archdiocese of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, modern Spain. He is a prominent fig ...

, the Archbishop of Compostela.Mann, pg. 293 Although Pope Callixtus II had made him Papal Legate of a number of Spanish provinces, Honorius informed Diego that he had been made aware of Diego's ambitions and subtly advised him to keep his ambition in check. Still hoping to be promoted to the office of Legate of Spain, Diego sent envoys to Rome, carrying with them 300 gold Almoravid

The Almoravid dynasty ( ar, المرابطون, translit=Al-Murābiṭūn, lit=those from the ribats) was an imperial Berber Muslim dynasty centered in the territory of present-day Morocco. It established an empire in the 11th century that ...

coins, two hundred and twenty for Honorius and another eighty for the Curia

Curia (Latin plural curiae) in ancient Rome referred to one of the original groupings of the citizenry, eventually numbering 30, and later every Roman citizen was presumed to belong to one. While they originally likely had wider powers, they came ...

. Honorius repeated that his hands were tied, as he had just appointed a cardinal for that post.Mann, pg. 294

Nevertheless, Honorius was not prepared to completely alienate Diego, and when the Archbishop of Braga

The Archdiocese of Braga ( la, Archidioecesis Bracarensis) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or archdiocese of the Catholic Church in Portugal. It is known for its use of the Rite of Braga, a use of the liturgy distinct from the Roman R ...

nominated a successor to the vacant See of Coimbra

Coimbra (, also , , or ) is a city and a municipality in Portugal. The population of the municipality at the 2011 census was 143,397, in an area of .

The fourth-largest urban area in Portugal after Lisbon, Porto, and Braga, it is the largest cit ...

, Honorius reprimanded the archbishop for usurping the rights of Diego, who should have been the one to nominate a successor. Honorius also demanded that the Archbishop of Braga present himself before Honorius on the second Sunday after Easter in 1129 to answer for his actions. Honorius also ensured that Diego should play a leading role in the Synod of Carrión (February 1130), having his legate approach Diego and ask for his assistance during the synod.

Honorius also wished to promote the ongoing struggle against the Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

in Spain, and to that end he bestowed the city of Tarragona

Tarragona (, ; Phoenician: ''Tarqon''; la, Tarraco) is a port city located in northeast Spain on the Costa Daurada by the Mediterranean Sea. Founded before the fifth century BC, it is the capital of the Province of Tarragona, and part of Tarr ...

, which had been recently captured from the Moors, to Robert d'Aguiló.Mann, pg. 296 Robert travelled to Rome to receive the gift from Honorius in 1128.

Establishment of the Templars and affairs in the East

In 1119, a new religious order had been established by some French noblemen. Called the Knights Templar, they were to protect Christian pilgrims entering the Holy Land and to defend the conquests of the

In 1119, a new religious order had been established by some French noblemen. Called the Knights Templar, they were to protect Christian pilgrims entering the Holy Land and to defend the conquests of the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

. However, by the pontificate of Honorius II, they had not yet received any official sanction from the papacy. To rectify this situation, some members of the order appeared before the Council of Troyes in 1129, where the Council expressed its approval of the order and commissioned Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, O. Cist. ( la, Bernardus Claraevallensis; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templars, and a major leader in the reformation of the Benedictine Order throug ...

to draw up the order's rules, which now included vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. The order and the rules were subsequently approved by Honorius.

Honorius, as suzerain of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem ( la, Regnum Hierosolymitanum; fro, Roiaume de Jherusalem), officially known as the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem or the Frankish Kingdom of Palestine,Example (title of works): was a Crusader state that was establish ...

, re-confirmed the election of King Baldwin II of Jerusalem

Baldwin II, also known as Baldwin of Bourcq or Bourg (; – 21August 1131), was Count of Edessa from 1100 to 1118, and King of Jerusalem from 1118 until his death. He accompanied his cousins Godfrey of Bouillon and Baldwin of Boulogne to th ...

and established him as the royal patron of the Templars.Mann, pg. 300 Honorius tried to manage as best he could the rivalries of the different princes and high-ranking ecclesiastics that were destabilising the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Long-standing arguments over areas of jurisdiction between the Latin Patriarchs of Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

and Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

were a constant source of irritation to Honorius. Honorius supported the claims of William of Malines, the new Archbishop of Tyre

The see of Tyre was one of the most ancient dioceses in Christianity. The existence of a Christian community there already in the time of Saint Paul is mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles. Seated at Tyre, which was the capital of the Roman provi ...

who claimed jurisdiction over some of the sees that had traditionally belonged to Bernard of Valence Bernard of Valence (died 1135) was the Latin Patriarch of Antioch from 1100 to 1135.

Originally from Valence, Bernard was part of the army of Raymond of Saint-Gilles and attended the Battle of Harran, and Battle of Sarmada with Roger of Salerno ...

, the Patriarch of Antioch.Mann, pg. 301 Bernard refused to give up his claims to the sees, and William travelled to Rome and presented his case before Honorius. The pope sent a legate back to Palestine with instructions that Bernard was to acquiesce and that the various bishops were to submit to William of Malines within forty days.Mann, pg. 302 Bernard managed to resist implementing Honorius's instructions, and soon Honorius was too ill to do anything about it.

Death of Honorius II

After almost a year of suffering a painful illness,Mann, pg. 303 Honorius fell seriously ill in early 1130. Cardinal Aymeric and the Frangipani family began planning their next moves, and Honorius was taken to theSan Gregorio Magno al Celio

San Gregorio Magno al Celio, also known as San Gregorio al Celio or simply San Gregorio, is a church in Rome, Italy, which is part of a monastery of monks of the Camaldolese branch of the Benedictine Order. On 10 March 2012, the 1,000th annive ...

monastery, which was located in the territory controlled by the Frangipani. Supporters of the Pierleoni family, already preparing to back Pietro Pierleoni on a rumor that Honorius had died, stormed the monastery of the dying Honorius, hoping to force the election of Pietro.Mann, pg. 304 Only the sight of the still living Honorius in full pontifical robes forced them to disperse.

Nevertheless, Cardinal Aymeric's plans had not yet reached fruition when Honorius died on the evening of 13 February 1130. The cardinals supporting the Frangipani immediately closed the monastery gates and refused to allow anyone inside. The next day, and contrary to the usual customs, Honorius was quickly buried without any pomp or ceremony in the monastery, as the hand-picked cardinals got around to electing Gregorio Papareschi, who took the name Pope Innocent II. At the same time, the excluded cardinals, most of whom were supporters of the Pierleoni family, elected Pietro Pierleoni, who took the name Anacletus II, throwing the church once again into schism.Levillain, pgs. 732–733 Honorius eventually transferred from the monastery to the Lateran for reburial once Innocent II had been elected. He was buried in the south transept next to the body of Callixtus II.

Legacy

The way in which Honorius was elected meant that he became a creature, not only of Cardinal Aymeric, but also of the Frangipani family.Mann, pg. 236 Aymeric expanded his powerbase further, with Honorius elevating mostly non-Roman candidates to the college of cardinals, while papal legates were now chosen solely within the papal circle. Honorius favoured the newer monastic orders, such as the Augustinians, a departure from the policies of the older Gregorian popes who favoured traditional orders such as the Benedictines. At the same time, he found himself drawn into the continued chaos of local Roman politics, as the Frangipani enjoyed their influence at the papal court, while the Pierleoni family continually fought against them and against Honorius. Their ceaseless infighting, repressed during the pontificate of Calixtus II, broke out again, and Honorius found he did not have the resources to suppress the Pierleoni, nor the authority to rein in the Frangipani. Honorius was required to engage in a number of petty wars in Rome, which wasted his time and were in the long haul unsuccessful in restoring order in the streets. The continued chaos would be instrumental in the events that saw the resurrection of Republican sentiment in the city and the eventual establishment of theCommune of Rome

The Commune of Rome ( it, Comune di Roma) was established in 1144 after a rebellion led by Giordano Pierleoni. Pierleoni led a people's revolt due to the increasing powers of the Pope and the entrenched powers of the nobility. The goal of the ...

in the following decade.

See also

*List of popes

This chronological list of popes corresponds to that given in the ''Annuario Pontificio'' under the heading "I Sommi Pontefici Romani" (The Roman Supreme Pontiffs), excluding those that are explicitly indicated as antipopes. Published every ye ...

*Cardinals created by Honorius II

Pope Honorius II (r. 1124–1130) created 27 cardinals in six consistories held throughout his pontificate. This included his successors Anastasius IV and Celestine II

Pope Celestine II ( la, Caelestinus II; died 8 March 1144), born Guido di ...

Sources

* Bergamo, Mario da (1968) OFM Cist. uigi Pellegrini "La duplice elezione papale del 1130: I precedenti immediati e i protagonisti," ''Contributi dell' Istituto di Storia Medioevale, Raccolta di studi in memoria di Giovanni Soranzo'' II (Milan), 265–302. * Catholic Encyclopedia: Honorius II''Catholic Encyclopedia'':Honorius II * * Gregorovius, Ferdinand (1896) ''History of Rome in the Middle Ages'', Volume IV. 2 second edition, revised (London: George Bell). * Hüls, Rudolf (1977) ''Kardinäle, Klerus und Kirchen Roms: 1049–1130 ''(Tübingen) ibliothek des Deutschen Historischen Instituts in Rom, Band 48 * Levillain, Philippe (2002) ''The Papacy: An Encyclopedia, Vol II: Gaius-Proxies'', Routledge * * Pandulphus Pisanus (1723) "Vita Calisti Papae II," "Vita Honorii II," Ludovico Antonio Muratori (editor), ''Rerum Italicarum Scriptores'' III. 1 (Milan), pp. 418–419; 421–422. * Stroll, Mary (1987) ''The Jewish Pope'' (New York: Brill 1987). * Stroll, Mary (2005) ''Calixtus II'' (New York: Brill 2005). * Thomas, P. C. (2007) ''A Compact History of the Popes'', St Pauls BYB

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Honorius 02 1060 births 1130 deaths People from the Province of Bologna Popes Italian popes Cardinal-bishops of Ostia 12th-century Italian Roman Catholic bishops 12th-century popes Cardinals created by Pope Urban II Burials at the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran