Polish population transfers (1944–1946) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Polish population transfers in 1944–1946 from the eastern half of prewar

The Polish population transfers in 1944–1946 from the eastern half of prewar

Russo-Polish War

in

"The conflict began when the Polish head of state

, By R. J. Crampton, page 50 OUN directed its violence not only against the Poles but also against Jews and other Ukrainians who wished for a peaceful resolution to the Polish–Ukrainian conflict.''Galicia''

, By C. M. Hann and Paul R. Magocsi, page 148

Google Print, p.91-93

The city of Vilnius was considered a historical capital of Lithuania; however, in the early 20th century its population was around 40% Polish, 30% Jewish and 20% Russian and Belarusian, with only about 2–3% self-declared Lithuanians. The government considered the rural Polish population important to the agricultural economy, and believed those people would be relatively amenable to assimilation policies (Lithuanization). But the government encouraged expulsion of Poles from Vilnius, and facilitated it. The result was a rapid Polonization, depolonization and Lithuanization of the city (80% of the Polish population was removed). Furthermore, the Lithuanian ideology of "Ethnographic Lithuania" declared that many people who identified as Polish were in fact "polonized Lithuanians". The rural population was denied the right to leave Lithuania, due to their lack of official pre-war documentation showing Polish citizenship. Contrary to the government's agreement with Poland, many individuals were threatened with either arrest or having to settle outstanding debts if they chose repatriation. Soviet authorities persecuted individuals connected to the Polish resistance (Armia Krajowa and Polish Underground State). In the end, about 50% of the 400,000 people registered for relocation were allowed to leave. Political scientist Dovilė Budrytė estimated that about 150,000 people left for Poland.Dovile Budryte, ''Taming Nationalism?: Political Community bBilding in the Post-Soviet Baltic States'', Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005,

Google Print, p.147

The Polish population transfers in 1944–1946 from the eastern half of prewar

The Polish population transfers in 1944–1946 from the eastern half of prewar Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

(also known as the expulsions of Poles from the Kresy macroregion), were the forced migration

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, g ...

s of Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in ...

toward the end and in the aftermath of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. These were the result of Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

policy that was ratified by the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

. Similarly, the Soviet Union had enforced policies between 1939 and 1941 which targeted and expelled ethnic Poles residing in the Soviet zone of occupation following the Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

. The second wave of expulsions resulted from the retaking of Poland by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

during the Soviet counter-offensive. It took over territory for its republic of Ukraine, a shift that was ratified at the end of World War II by the Soviet Union's then Allies of the West.

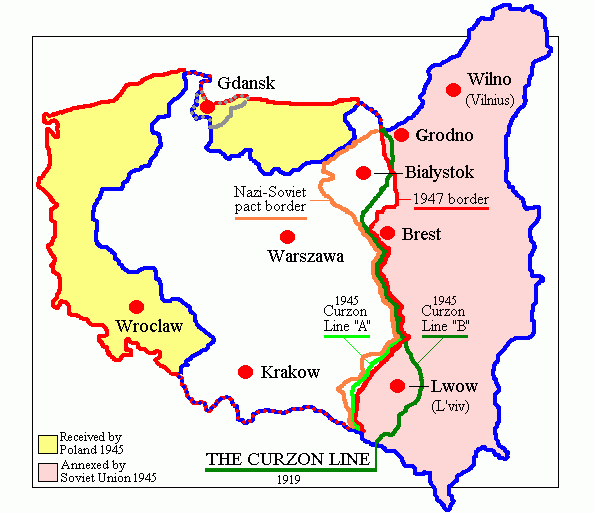

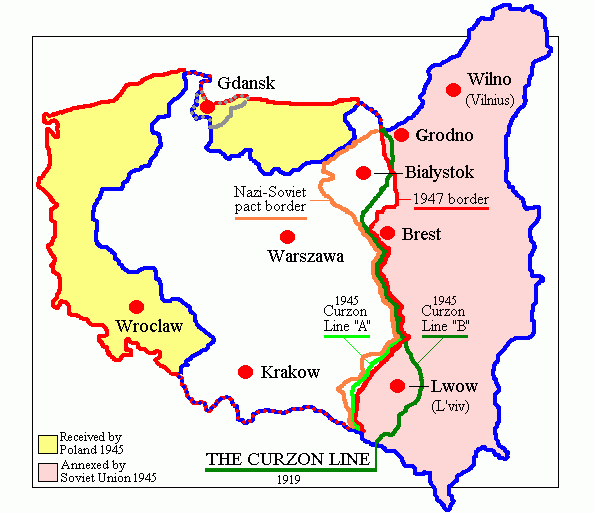

The postwar population transfers, targeting Polish nationals, were part of an official Soviet policy that affected more than one million Polish citizens, who were removed in stages from the Polish areas annexed by the Soviet Union. After the war, following Soviet demands laid out during the Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference ( codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embass ...

of 1943, the Kresy macroregion was formally incorporated into the Ukrainian, Belarusian and Lithuanian Republics of the Soviet Union

The Republics of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics or the Union Republics ( rus, Сою́зные Респу́блики, r=Soyúznye Respúbliki) were National delimitation in the Soviet Union, national-based administrative units of ...

. This was agreed at the Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris P ...

of Allies in 1945, to which the acting Government of the Republic of Poland in exile was not invited.

The ethnic displacement of Poles (and also of ethnic Germans) was agreed to by the Allied leaders: Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

of the United Kingdom, Franklin D. Roosevelt of the U.S., and Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

of the USSR, during the conferences at both Tehran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

and Yalta

Yalta (: Я́лта) is a resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Cri ...

. The Polish transfers were among the largest of several post-war expulsions in Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known a ...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

, which displaced a total of about 20 million people.

According to official data, during the state-controlled expulsion between 1945 and 1946, roughly 1,167,000 Poles left the westernmost republics of the Soviet Union, less than 50% of those who registered for population transfer. Another major ethnic Polish transfer took place after Stalin's death, in 19551959.

The process is variously known as expulsion, deportation

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. The term ''expulsion'' is often used as a synonym for deportation, though expulsion is more often used in the context of international law, while deportation ...

, depatriation, or repatriation

Repatriation is the process of returning a thing or a person to its country of origin or citizenship. The term may refer to non-human entities, such as converting a foreign currency into the currency of one's own country, as well as to the pro ...

, depending on the context and the source. The term ''repatriation'', used officially in both communist-controlled Poland and the USSR, was a deliberate distortion, as deported peoples were leaving their homeland rather than returning to it. It is also sometimes referred to as the 'first repatriation' action, in contrast with the ' second repatriation' of 19551959. In a wider context, it is sometimes described as a culmination of a process of "de-Polonization" of the areas during and after the world war. The process was planned and carried out by the communist regimes of the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nati ...

and of post-war Poland. Many of the deported Poles were settled in formerly German eastern provinces; after 1945, these were referred to as the " Recovered Territories" of the People's Republic of Poland

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million ne ...

.

Background

The history of ethnic Polish settlement in what is now Ukraine and Belarus dates to 1030–31. More Poles migrated to this area after theUnion of Lublin

The Union of Lublin ( pl, Unia lubelska; lt, Liublino unija) was signed on 1 July 1569 in Lublin, Poland, and created a single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest countries in Europe at the time. It replaced the per ...

in 1569, when most of the territory became part of the newly established Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

. From 1657 to 1793, some 80 Roman Catholic churches and monasteries were built in Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

alone. The expansion of Catholicism in Lemkivshchyna

The Lemko Region (; pl, Łemkowszczyzna; uk, Лемківщина, translit=Lemkivshchyna) is an ethnographic area in southern Poland that has traditionally been inhabited by the Lemko people. The land stretches approximately long and wid ...

, Chełm Land, Podlaskie, Brześć land, Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

, Volhynia and Right bank Ukraine

Right-bank Ukraine ( uk , Правобережна Україна, ''Pravoberezhna Ukrayina''; russian: Правобережная Украина, ''Pravoberezhnaya Ukraina''; pl, Prawobrzeżna Ukraina, sk, Pravobrežná Ukrajina, hu, Jobb p ...

was accompanied by the process of gradual Polonization

Polonization (or Polonisation; pl, polonizacja)In Polish historiography, particularly pre-WWII (e.g., L. Wasilewski. As noted in Смалянчук А. Ф. (Smalyanchuk 2001) Паміж краёвасцю і нацыянальнай ідэя� ...

of the eastern lands. Social and ethnic conflicts arose regarding the differences in religious practices between the Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

and the Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or " canonical ...

adherents during the Union of Brest in 1595-96, when the Metropolitan of Kiev-Halych broke relations with the Eastern Orthodox Church and accepted the authority of the Roman Catholic Pope and Vatican.

The partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

, toward the end of the 18th century, resulted in the expulsions of ethnic Poles from their homes in the east for the first time in the history of the nation. Some 80,000 Poles were escorted to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

by the Russian imperial army in 1864 in the single largest deportation action undertaken within the Russian Partition. "Books were burned; churches destroyed; priests murdered;" wrote Norman Davies

Ivor Norman Richard Davies (born 8 June 1939) is a Welsh-Polish historian, known for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland and the United Kingdom. He has a special interest in Central and Eastern Europe and is UNESCO Professor a ...

. Meanwhile, Ukrainians were officially considered "part of the Russian people

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 '' Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

".

The Russian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

and the Russian Civil War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Russian Civil War

, partof = the Russian Revolution and the aftermath of World War I

, image =

, caption = Clockwise from top left:

{{flatlist,

*Soldiers ...

of 1917-1922 brought an end to the Russian Empire.Goldstein, Erik (1992). ''Second World War 1939–1945''. Wars and Peace Treaties. London: Routledge. . According to Ukrainian sources from the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

period, during the Bolshevik revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

of 1917 the Polish population of Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the seventh-most populous city in Europe.

Ky ...

was 42,800. In July 1917, when relations between the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

(UNR) and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

became strained, the Polish Democratic Council of Kiev supported the Ukrainian side in its conflict with Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. Throughout the existence of UNR (1917–21), there was a separate ministry for Polish affairs, headed by Mieczysław Mickiewicz; it was set up by the Ukrainian side in November 1917. In that entire period, some 1,300 Polish-language schools were operating in Galicia, with 1,800 teachers and 84,000 students. In the region of Podolia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-centra ...

in 1917, there were 290 Polish schools.

Beginning in 1920, the Bolshevik and nationalist terror campaigns of the new war triggered the flight of Poles and Jews from Soviet Russia to newly sovereign Poland. In 1922 Bolshevik Russian Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

, with their Bolshevik allies in Ukraine overwhelmed the government of the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

, including the annexed Ukrainian territories into the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

. In that year, 120,000 Poles stranded in the east were expelled to the west and the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

. The Soviet census of 1926 recorded ethnic Poles as being of Russian or Ukrainian ethnicity, reducing their apparent numbers in Ukraine.

In the autumn of 1935, Stalin ordered a new wave of mass deportations of Poles from the western republics of the Soviet Union. This was also the time of his purges of different classes of people, many of whom were killed. Poles were expelled from the border regions in order to resettle the area with ethnic Russians and Ukrainians, but Stalin had them deported to the far reaches of Siberia and Central Asia. In 1935 alone 1,500 families were deported to Siberia from Soviet Ukraine. In 1936, 5,000 Polish families were deported to Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

. The deportations were accompanied by the gradual elimination of Polish cultural institutions. Polish-language newspapers were closed, as were Polish-language classes throughout Ukraine.

Soon after the wave of deportations, the Soviet NKVD orchestrated the Genocide of Poles in the Soviet Union. The Polish population in the USSR had officially dropped by 165,000 in that period according to the official Soviet census of 1937–38; Polish population in the Ukrainian SSR decreased by about 30%.

Second Polish Republic

Amidst several border conflicts, Poland re-emerged as a sovereign state in 1918 followingPartitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

. The Polish-Ukrainian alliance was unsuccessful, and the Polish-Soviet war continued until the Treaty of Riga was signed in 1921. The Soviet Union did not officially exist before 31 December 1922.See for instancRusso-Polish War

in

Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

"The conflict began when the Polish head of state

Józef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Naczelnik państwa, Chief of State (1918–1922) and Marshal of Poland, First Marshal of Second Polish Republic, Poland (from 1920). He was ...

formed an alliance with the Ukrainian nationalist leader Symon Petlyura (21 April 1920) and their combined forces began to overrun Ukraine, occupying Kiev on 7 May." The disputed territories were split in Riga between the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

and the Soviet Union representing Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

(part of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

after 1923). In the following few years in Kresy, the lands assigned to sovereign Poland, some 8,265 Polish farmers were resettled with help from the government. The overall number of settlers in the east was negligible as compared to the region's long-term residents. For instance in the Volhynian Voivodeship (1,437,569 inhabitants in 1921), the number of settlers did not exceed 15,000 people (3,128 refugees from Bolshevist Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

, roughly 7,000 members of local administration, and 2,600 military settlers). Approximately 4 percent of the newly arrived settlers lived on land granted to them. The majority either rented their land to local farmers, or moved to the cities.

Tensions between the Ukrainian minority in Poland

Ukrainians in Poland have various legal statuses: ethnic minority, temporary and permanent residents, and refugees.

According to the Polish census of 2011, the Ukrainian minority in Poland was composed of approximately 51,000 people (including ...

and the Polish government escalated. On 12 July 1930, activists of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), helped by the UVO, began the so-called ''sabotage action'', during which Polish estates were burned, and roads, rail lines and telephone connections were destroyed. The OUN used terrorism and sabotage in order to force the Polish government into actions that would cause a loss of support for the more moderate Ukrainian politicians ready to negotiate with the Polish state.''Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century'', By R. J. Crampton, page 50 OUN directed its violence not only against the Poles but also against Jews and other Ukrainians who wished for a peaceful resolution to the Polish–Ukrainian conflict.''Galicia''

, By C. M. Hann and Paul R. Magocsi, page 148

Invasion of Poland

The 1939Soviet invasion of Poland

The Soviet invasion of Poland was a military operation by the Soviet Union without a formal declaration of war. On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east, 16 days after Nazi Germany invaded Poland from the west. Subs ...

during World War II was subsequently accompanied by the Soviets forcibly deporting hundreds of thousands of Polish citizens to distant parts of the Soviet Union: Siberia and Central Asia. Five years later, for the first time, the Supreme Soviet formally acknowledged that the Polish nationals expelled after the Soviet invasion were not Soviet citizens, but foreign subjects. Two decrees were signed on 22 June and 16 August 1944 to facilitate the release of Polish nationals from captivity.

Deportations

After the signing of the secret Molotov-Ribbentrop pact in 1939 between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, Germanyinvaded

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

Western Poland. Two weeks later, the Soviet Union invaded eastern Poland. As a result, Poland was divided between the Germans and the Soviets (see Polish areas annexed by the Soviet Union). With the annexation of the Kresy in 1939, modern-day Western Ukraine was annexed to Soviet Ukraine

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

, and Western Belarus to Soviet Belorussia, respectively. Spreading terror throughout the region, the Soviet secret police (NKVD) accompanying the Red Army murdered Polish prisoners of war. Polish Institute of National Remembrance

The Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation ( pl, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej – Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu, abbreviated IPN) is a Polish state resea ...

. Internet Archive, 16.10.03. Retrieved 16 July 2007. From 1939 to 1941 the Soviets also forcibly deported specific social groups deemed "untrustworthy" to forced labor facilities in Kazakhstan and Siberia. Many children, elderly and sick died during the journeys in cargo trains which lasted weeks. Whereas the Polish government-in-exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile ( pl, Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Pola ...

put the number of deported Polish citizens at 1,500,000 and some Polish estimates reached 1,600,000 to 1,800,000 persons, historians consider these evaluations as exaggerated. Alexander Guryanov calculated that 309,000 up to 312,000 Poles were deported from February 1940 to June 1941. According to N.S. Lebedeva the deportations involved about 250,000 persons. The most conservative Polish counts based on Soviet documents and published by the Main Commission to Investigate Crimes Against the Polish Nation in 1997 amounted to a grand total of 320,000 persons deported. Sociologist Tadeusz Piotrowski argues that various other smaller deportations, prisoners of war and political prisoners should be added for a grand total of 400,000 to 500,000 deported.

By 1944, the population of ethnic Poles in Western Ukraine was 1,182,100. The Polish government in exile

The Polish government-in-exile, officially known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile ( pl, Rząd Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej na uchodźstwie), was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Pola ...

in London affirmed its position of retaining the 1939 borders. Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

, however, approached Stalin personally to keep the territories gained through the illegal and secret Molotov-Ribbentrop pact under continued Soviet occupation.

The document regarding the resettlement of Poles from the Ukrainian and Belorussian SSRs to Poland was signed 9 September 1944 in Lublin

Lublin is the ninth-largest city in Poland and the second-largest city of historical Lesser Poland. It is the capital and the center of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 336,339 (December 2021). Lublin is the largest Polish city east of ...

by Khrushchev and the head of the Polish Committee of National Liberation

The Polish Committee of National Liberation (Polish: ''Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego'', ''PKWN''), also known as the Lublin Committee, was an executive governing authority established by the Soviet-backed communists in Poland at the la ...

Edward Osóbka-Morawski (the corresponding document with the Lithuanian SSR was signed on 22 September). The document specified who was eligible for the resettlement (it primarily applied to all Poles and Jews who were citizens of the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of the First World ...

before 17 September 1939, and their families), what property they could take with them, and what aid they would receive from the corresponding governments. The resettlement was divided into two phases: first, the eligible citizens were registered as wishing to be resettled; second, their request was to be reviewed and approved by the corresponding governments. About 750,000 Poles and Jews from the western regions of Ukraine were deported, as well as about 200,000 each from western Belarus and from Lithuanian SSR each. The deportations continued until August 1, 1946.

Postwar transfers from Ukraine

Toward the end ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, tensions between the Polish AK and Ukrainians escalated into the Massacres of Poles in Volhynia

The massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia ( pl, rzeź wołyńska, lit=Volhynian slaughter; uk, Волинська трагедія, lit=Volyn tragedy, translit=Volynska trahediia), were carried out in German-occupied Poland by the ...

, led by the nationalist Ukrainian groups including the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army

The Ukrainian Insurgent Army ( uk, Українська повстанська армія, УПА, translit=Ukrayins'ka povstans'ka armiia, abbreviated UPA) was a Ukrainian nationalist paramilitary and later partisan formation. During World ...

. Although the Soviet government was trying to eradicate these organizations, it did little to support the Polish minority; and instead encouraged population transfer. The haste at which repatriation was done was such that the Polish leader Bolesław Bierut was forced to intercede and approach Stalin to slow down the deportation, as the post-war Polish government was overwhelmed by the sudden great number of refugees needing aid.

The Poles in southern Kresy (now Western Ukraine) were given the option of resettlement in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

or Poland, and most chose Poland.

The Polish government-in-exile in London directed their organizations (see Polish Secret State) in Lwów

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in Western Ukraine, western Ukraine, and the List of cities in Ukraine, seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is o ...

and other major centers in Eastern Poland to sit fast and not evacuate, promising that during peaceful discussions they would be able to keep Lwów within Poland. In response, Khrushchev introduced a different approach to dealing with this ''Polish problem''. Until this time, Polish children could be educated in Polish, according to the curriculum of pre-war Poland. Overnight this allowance was discontinued, and all Polish schools were required to teach the Soviet Ukrainian curriculum, with classes to be held only in Ukrainian and Russian. All males were told to prepare for mobilization into labor brigades within the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

. These actions were introduced specifically to encourage Polish emigration from Ukraine to Poland.

In January 1945, the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

arrested 772 Poles in Lviv (where, according to Soviet sources, on October 1, 1944, Poles represented 66.75% of population), among them 14 professors, 6 doctors, 2 engineers, 3 artists, and 5 Catholic priests. The Polish community was outraged about the arrests. The Polish underground press

Polish underground press, devoted to prohibited materials ( sl. pl, bibuła, lit. semitransparent blotting paper or, alternatively, pl, drugi obieg, lit. second circulation), has a long history of combatting censorship of oppressive regimes i ...

in Lviv characterized these acts as attempts to hasten the deportation of Poles from their city. Those arrested were released after they signed papers agreeing to emigrate to Poland. It is difficult to establish the exact number of Poles expelled from Lviv, but it was estimated as between 100,000 and 140,000.

Transfers from Belarus

In contrast to actions in the Ukrainian SSR, the communist officials in theByelorussian SSR

The Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR, or Byelorussian SSR; be, Беларуская Савецкая Сацыялістычная Рэспубліка, Bielaruskaja Savieckaja Sacyjalistyčnaja Respublika; russian: Белор� ...

did not actively support deportation of Poles. Belarusian officials made it difficult for Polish activists to communicate with '' tuteishians'' – people who were undecided as to whether they considered themselves Polish or Belarusian.Much of the rural population, who usually had no official identity documents, were denied the "right" of repatriation on the basis that they did not have documents stating they were Polish citizens. In what was described as a "fight for the people", Polish officials attempted to get as many people repatriated as possible, whereas the Belarusian officials tried to retain them, particularly the peasants, while deporting most of the Polish intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

. It is estimated that about 150,000 to 250,000 people were deported from Belarus. Similar numbers were registered as Poles but forced by the Belarusian officials to remain in Belarus or were outright denied registration as Poles.

In response, Poland followed a similar process in regards to the Belarusian population of the territory of the Białystok Voivodeship (1919–39), Białystok Voivodeship, which was partially retained by Poland after World War II. It sought to retain some of the Belarusian people.

From Lithuania

The resettlement of ethnic Poles from Lithuania saw numerous delays. Local Polish clergy were active in agitating against leaving, and the underground press called those who had registered for repatriation ''traitors''. Many ethnic Poles hoped that a post-war Peace Conference would assign the Vilnius region to Poland. After these hopes vanished, the number of people wanting to leave gradually increased, and they signed papers for thePeople's Republic of Poland

The Polish People's Republic ( pl, Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million ne ...

State Repatriation Office representatives.

The Lithuanian communist party was dominated by a nationalist faction which supported the removal of the Polish intelligentsia, particularly from the highly contested Vilnius region.Timothy Snyder, ''The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999'', Yale University Press, 2004, Google Print, p.91-93

The city of Vilnius was considered a historical capital of Lithuania; however, in the early 20th century its population was around 40% Polish, 30% Jewish and 20% Russian and Belarusian, with only about 2–3% self-declared Lithuanians. The government considered the rural Polish population important to the agricultural economy, and believed those people would be relatively amenable to assimilation policies (Lithuanization). But the government encouraged expulsion of Poles from Vilnius, and facilitated it. The result was a rapid Polonization, depolonization and Lithuanization of the city (80% of the Polish population was removed). Furthermore, the Lithuanian ideology of "Ethnographic Lithuania" declared that many people who identified as Polish were in fact "polonized Lithuanians". The rural population was denied the right to leave Lithuania, due to their lack of official pre-war documentation showing Polish citizenship. Contrary to the government's agreement with Poland, many individuals were threatened with either arrest or having to settle outstanding debts if they chose repatriation. Soviet authorities persecuted individuals connected to the Polish resistance (Armia Krajowa and Polish Underground State). In the end, about 50% of the 400,000 people registered for relocation were allowed to leave. Political scientist Dovilė Budrytė estimated that about 150,000 people left for Poland.Dovile Budryte, ''Taming Nationalism?: Political Community bBilding in the Post-Soviet Baltic States'', Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005,

Google Print, p.147

See also

* Expulsion of Germans after World War II * Polish minority in Belarus * Polish minority in Lithuania * Polish minority in Ukraine * Population transfer in the Soviet Union * Massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia * Operation Vistula * Repatriation of Ukrainians from Poland to USSR (1944-1946) * Recovered Territories * State Repatriation Office * Repatriation of Poles (1955–1959)References

Further reading

* Grzegorz Hryciuk, ''Przemiany narodowościowe i ludnościowe w Galicji Wschodniej i na Wołyniu w latach 1931–1948 {{DEFAULTSORT:Polish population transfers (1944-1946) Forced migration Aftermath of World War II in Poland British collusion with Soviet World War II crimes Ethnic groups in Belarus Poland in World War II 1940s in Belarus Ukraine in World War II Aftermath of World War II in the Soviet Union Poland–Ukraine relations Poland–Soviet Union relations Post–World War II forced migrations 1940s in the Soviet Union 1945 in international relations Anti-Polish sentiment in Europe Forced migration in the Soviet Union Soviet World War II crimes Soviet World War II crimes in Poland