Philaidae on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Philaidae or Philaids were a powerful noble family of ancient

After Miltiades took part in the failed

After Miltiades took part in the failed

After the Greek victories over Persia at Salamis,

After the Greek victories over Persia at Salamis,

Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

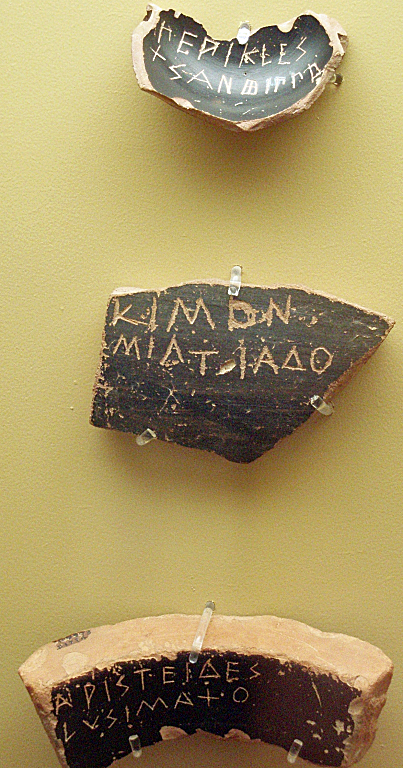

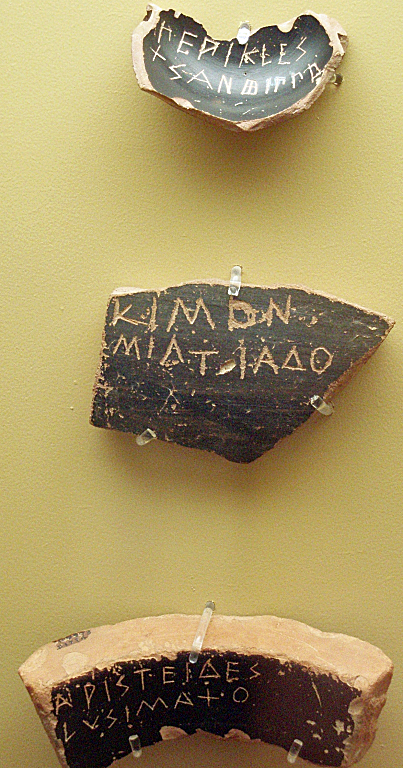

. They were conservative land owning aristocrats and many of them were very wealthy. The Philaidae produced two of the most famous generals in Athenian history: Miltiades the Younger and Cimon

Cimon or Kimon ( grc-gre, Κίμων; – 450BC) was an Athenian ''strategos'' (general and admiral) and politician.

He was the son of Miltiades, also an Athenian ''strategos''. Cimon rose to prominence for his bravery fighting in the naval Batt ...

.

The Philaids claimed descent from the mythological

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrat ...

Philaeus, son of Ajax

Ajax may refer to:

Greek mythology and tragedy

* Ajax the Great, a Greek mythological hero, son of King Telamon and Periboea

* Ajax the Lesser, a Greek mythological hero, son of Oileus, the king of Locris

* ''Ajax'' (play), by the ancient Gree ...

. The family originally came from Brauron

Brauron (; grc, Βραυρών) was one of the twelve cities of ancient Attica, but never mentioned as a ''deme'', though it continued to exist down to the latest times. It was situated on or near the eastern coast of Attica, between Steiria and ...

in Attica

Attica ( el, Αττική, Ancient Greek ''Attikḗ'' or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the city of Athens, the capital of Greece and its countryside. It is a peninsula projecting into the Aegean ...

. Later a prominent branch of the clan were based at Lakiadae west of Athens. In the late 7th century BC a Philaid called Agamestor married the daughter of Cypselus

Cypselus ( grc-gre, Κύψελος, ''Kypselos'') was the first tyrant of Corinth in the 7th century BC.

With increased wealth and more complicated trade relations and social structures, Greek city-states tended to overthrow their traditional her ...

, the powerful tyrant of Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part ...

. In 597 BC a man named Cypselus was archon

''Archon'' ( gr, ἄρχων, árchōn, plural: ἄρχοντες, ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem αρχ-, mean ...

of Athens. This Cypselus was probably grandson of the Corinthian tyrant of the same name and son of Agamestor.

Some years before 566 BC, a member of the Philaid clan, Hippocleides Hippocleides (also Hippoclides) ( grc-gre, Ἱπποκλείδης), the son of Teisander (Τείσανδρος), was an Athenian nobleman, who served as Eponymous Archon for the year 566 BC – 565 BC.

He was a member of the Philaidae, a wealthy ...

, was a suitor for the hand of Agariste, the daughter of the influential tyrant of Sicyon

Sicyon (; el, Σικυών; ''gen''.: Σικυῶνος) or Sikyon was an ancient Greek city state situated in the northern Peloponnesus between Corinth and Achaea on the territory of the present-day regional unit of Corinthia. An ancient mon ...

, Cleisthenes

Cleisthenes ( ; grc-gre, Κλεισθένης), or Clisthenes (c. 570c. 508 BC), was an ancient Athenian lawgiver credited with reforming the constitution of ancient Athens and setting it on a democratic footing in 508 BC. For these accomplishm ...

. However Hippocleides lost out to Megacles

Megacles or Megakles ( grc, Μεγακλῆς) was the name of several notable men of ancient Athens, as well as an officer of Pyrrhus of Epirus.

First archon

The first Megacles was possibly a legendary archon of Athens from 922 BC to 892 BC.

A ...

from the rival Alcmaeonid

The Alcmaeonidae or Alcmaeonids ( grc-gre, Ἀλκμαιωνίδαι ; Attic: ) were a wealthy and powerful noble family of ancient Athens, a branch of the Neleides who claimed descent from the mythological Alcmaeon, the great-grandson of Nesto ...

clan when Cleisthenes was unimpressed with a drunken Hippocleides who stood on his head and kicked his heels in the air at a banquet.

Tyrants of the Thracian Chersonese

In c.560-556 BC aThracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied ...

tribe, the Dolonci Dolonci or Dolonki ( el, Δόλογκοι) is the name of a Thracian tribe in Thracian Chersonese. They are mentioned by Herodotus.

References

See also

*List of Thracian tribes

This is a list of ancient tribes in Thrace and Dacia ( grc, Θρ� ...

, offered the rule of the Thracian Chersonese

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied ...

(a peninsula in a strategic location dominating the grain route through the Hellespont

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

) to the Philaid Miltiades the Elder

Miltiades the Elder (ca. 590 – 525 BC) was an Athenian

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seve ...

, the son of Cypselus the archon. Miltiades accepted the offer and became tyrant of the Chersonese. He built a wall across the Bulair Isthmus to protect the peninsula from raiders from Thrace. Pisistratus

Pisistratus or Peisistratus ( grc-gre, wikt:Πεισίστρατος, Πεισίστρατος ; 600 – 527 BC) was a politician in ancient Athens, ruling as tyrant in the late 560s, the early 550s and from 546 BC until his death. His unificat ...

, the tyrant of Athens, did not object to Miltiades leaving Athens to set himself up as a semi-independent ruler on the far side of the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi ( Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

as it removed a potential rival from the city and gave him a useful role as an ally of Athens in a strategically important location.

Meanwhile a Philaid called Cimon Coalemos, ('coalemos' meaning simpleton), won the prestigious Olympic

Olympic or Olympics may refer to

Sports

Competitions

* Olympic Games, international multi-sport event held since 1896

** Summer Olympic Games

** Winter Olympic Games

* Ancient Olympic Games, ancient multi-sport event held in Olympia, Greece bet ...

chariot race three times in succession during the rule of Pisistratid tyrants. He earned a recall from exile by dedicating his second victory to Pisistratus but when he unwisely continued his winning streak by notching up a famous third consecutive Olympic victory he fell foul of Pisistratus' sons Hippias

Hippias of Elis (; el, Ἱππίας ὁ Ἠλεῖος; late 5th century BC) was a Greek sophist, and a contemporary of Socrates. With an assurance characteristic of the later sophists, he claimed to be regarded as an authority on all subjects ...

and Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the e ...

who had him assassinated.

Around 534 BC Miltiades the Elder died and the tyranny of the Thracian Chersonese passed to his step-brother's son Stesagoras. Then in c.520 BC Stesagoras was succeeded by his brother Miltiades the Younger, son of Cimon Coalemus. This younger Miltiades cemented good relations with neighbouring Thracian tribes by marrying Hegesipyle daughter of the Thracian king Olorus

Olorus ( gr, Ὄλορος) was the name of a king of Thrace. His daughter Hegesipyle married the Athenian statesman and general Miltiades, who defeated the Persians at the Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC during ...

.

Miltiades the Younger also served with King Darius I

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his ...

of Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

during his campaign against the Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Cent ...

in c.513 BC and when the Greek contingents were left guarding a bridge over the Danube River

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

Miltiades tried to convince his fellow Greeks to demolish the bridge so as to leave the Persian king stranded in Scythia (or so he later claimed).

Miltiades returns to Athens

After Miltiades took part in the failed

After Miltiades took part in the failed Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC. At the heart of the rebellion was the dissatisf ...

against the Persian Empire he fled the Chersonese and returned to Athens in c.493 BC. He survived a prosecution for tyranny and when the Persians landed at Marathon

The marathon is a long-distance foot race with a distance of , usually run as a road race, but the distance can be covered on trail routes. The marathon can be completed by running or with a run/walk strategy. There are also wheelchair div ...

in 490 BC

Miltiades, as one of ten generals ''(strategoi

''Strategos'', plural ''strategoi'', Latinized ''strategus'', ( el, στρατηγός, pl. στρατηγοί; Doric Greek: στραταγός, ''stratagos''; meaning "army leader") is used in Greek to mean military general. In the Hellenist ...

)'' played the major part in winning the battle for Athens.

Miltiades now enjoyed great prestige at Athens as the victor of Marathon. The following year he was given command of forces which besieged the pro-Persian island of Paros

Paros (; el, Πάρος; Venetian: ''Paro'') is a Greek island in the central Aegean Sea. One of the Cyclades island group, it lies to the west of Naxos, from which it is separated by a channel about wide. It lies approximately south-east of ...

. However the expedition was ill-fated as Miltiades failed to capture the city of Paros and fell off a wall during the siege operations and arrived back in Athens with gangrene

Gangrene is a type of tissue death caused by a lack of blood supply. Symptoms may include a change in skin color to red or black, numbness, swelling, pain, skin breakdown, and coolness. The feet and hands are most commonly affected. If the gan ...

in his leg.

The debacle of the Parian expedition led Miltiades' enemies to renew their attacks on him in court and just one year after the victory at Marathon Miltiades the Younger died from his infected leg.

Cimon leads the war against Persia

After the Greek victories over Persia at Salamis,

After the Greek victories over Persia at Salamis, Plataea

Plataea or Plataia (; grc, Πλάταια), also Plataeae or Plataiai (; grc, Πλαταιαί), was an ancient city, located in Greece in southeastern Boeotia, south of Thebes.Mish, Frederick C., Editor in Chief. “Plataea.” '' Webst ...

and Mycale

Mycale (). also Mykale and Mykali ( grc, Μυκάλη, ''Mykálē''), called Samsun Dağı and Dilek Dağı (Dilek Peninsula) in modern Turkey, is a mountain on the west coast of central Anatolia in Turkey, north of the mouth of the Maeander an ...

in 480-479 BC the Athenians soon took the lead in launching an offensive against Persian forces in the Aegean region. The Philaid Cimon

Cimon or Kimon ( grc-gre, Κίμων; – 450BC) was an Athenian ''strategos'' (general and admiral) and politician.

He was the son of Miltiades, also an Athenian ''strategos''. Cimon rose to prominence for his bravery fighting in the naval Batt ...

, son of Miltiades the Younger and grandson of Cimon the Olympic victor, became the leading general of this offensive phase of the Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the ...

.

Cimon drove the Persians out of the city of Eion

Eion ( grc-gre, Ἠϊών, ''Ēiṓn''), ancient Chrysopolis, was an ancient Greek Eretrian colony in Thracian Macedonia specifically in the region of Edonis. It sat at the mouth of the Strymon River which flows into the Aegean from the interio ...

in Thrace in 477–476 BC. After clearing pirates from the island of Scyros

Skyros ( el, Σκύρος, ), in some historical contexts Latinized Scyros ( grc, Σκῦρος, ), is an island in Greece, the southernmost of the Sporades, an archipelago in the Aegean Sea. Around the 2nd millennium BC and slightly later, the ...

and putting down a rebellion on Naxos

Naxos (; el, Νάξος, ) is a Greek island and the largest of the Cyclades. It was the centre of archaic Cycladic culture. The island is famous as a source of emery, a rock rich in corundum, which until modern times was one of the best ab ...

Cimon in 466 BC launched a bold attack on large Persian land and naval forces gathering at the Eurymedon River Eurymedon may refer to:

Historical figures

*Eurymedon (strategos) (died 413 BC), one of the Athenian generals (strategoi) during the Peloponnesian War

*Eurymedon of Myrrhinus, married Plato's sister, Potone; he was the father of Speusippus

* Eury ...

in Pamphylia

Pamphylia (; grc, Παμφυλία, ''Pamphylía'') was a region in the south of Asia Minor, between Lycia and Cilicia, extending from the Mediterranean to Mount Taurus (all in modern-day Antalya province, Turkey). It was bounded on the north b ...

. In the greatest victory of his career Cimon led the Athenian and Delian League

The Delian League, founded in 478 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of Pla ...

forces to a crushing double victory over the Persians destroying the Persian fleet while heavily defeating their army.

Later Cimon expelled the Persians from the Thracian Chersonese and put down a revolt on Thasos

Thasos or Thassos ( el, Θάσος, ''Thásos'') is a Greek island in the North Aegean Sea. It is the northernmost major Greek island, and 12th largest by area.

The island has an area of and a population of about 13,000. It forms a separate r ...

. He was acquitted on a charge of bribery largely through the efforts of his half-sister Elpinice. In c.462 BC Cimon encouraged the Athenians to send military aid to the Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referr ...

ns who were trying to put down a major revolt by the Helots

The helots (; el, εἵλωτες, ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their ...

in the wake of an earthquake which had heavily damaged Sparta. But the conservative Spartans became worried by the revolutionary democratic spirit of the Athenian troops and sent Cimon and his army back home to Athens.

War between Athens and Sparta soon followed this rebuff and Cimon as a prominent pro-Spartan advocate was ostracised from Athens for ten years. He was recalled in 451 BC to lead an Athenian attack against the Persians in Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is ...

but he died at the Siege of Citium.

Thucydides

Thucydides, son of Melesias, the leader of the anti-Periclean conservative party during the 440s BC, was a relative of Cimon and a member of the Philaid clan. Thucydides, son of Olorus, the great historian of thePeloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of ...

was also a Philaid according to the biographer Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

who notes that his remains were returned to Athens and placed in Cimon's family vault and that his father's name, Olorus, was the same as Cimon's grandfather.

Later Philaids

Lacedaimonius the son of Cimon was named afterLacedaimon

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

, another name for Sparta. This was an indication of the admiration his father Cimon felt for the Spartans and their way of life. Lacedaimonius was one of the three Athenian commanders at the Battle of Sybota

The Battle of Sybota ( grc, Σύβοτα) took place in 433 BCE between Corcyra (modern Corfu) and Corinth. It was one of the immediate catalysts for the Peloponnesian War.

History

Corinth had been in dispute with Corcyra, an old Corinthian col ...

in 433 BC.

Epicurus

Epicurus (; grc-gre, Ἐπίκουρος ; 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher and sage who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy. He was born on the Greek island of Samos to Athenian parents. Influence ...

the philosopher (341 BC–270 BC) was descended from Athenian settlers on the island of Samos

Samos (, also ; el, Σάμος ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a sepa ...

and was of the Philaid clan. Eurydice of Athens, a descendant of Miltiades the Younger, married Ophellas

Ophellas or Ophelas (fl. c. 350 – 308 BC) was an Ancient Macedonian soldier and politician. Born in Pella in Macedonia, he was a member of the expeditionary army of Alexander the Great in Asia, and later acted as Ptolemaic governor of Cyre ...

the Macedonian who was ruler of Cyrene. After the death of Ophellas she became the wife of the Antigonid

The Antigonid dynasty (; grc-gre, Ἀντιγονίδαι) was a Hellenistic dynasty of Dorian Greek provenance, descended from Alexander the Great's general Antigonus I Monophthalmus ("the One-Eyed") that ruled mainly in Macedonia.

History

...

king Demetrius Poliorcetes

Demetrius I (; grc, Δημήτριος; 337–283 BC), also called Poliorcetes (; el, Πολιορκητής, "The Besieger"), was a Macedonian nobleman, military leader, and king of Macedon (294–288 BC). He belonged to the Antigonid dynasty ...

, the famous 'besieger of cities', after he took control of Athens in 307 BC.Plutarch, Demetrius 14

References

{{reflist Ancient Athenian families