Patrick Hamilton (martyr) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Patrick Hamilton (1504 – 29 February 1528) was a Scottish churchman and an early Protestant Reformer in Scotland. He travelled to Europe, where he met several of the leading reformed thinkers, before returning to Scotland to preach. He was tried as a heretic by Archbishop

Patrick Hamilton (1504 – 29 February 1528) was a Scottish churchman and an early Protestant Reformer in Scotland. He travelled to Europe, where he met several of the leading reformed thinkers, before returning to Scotland to preach. He was tried as a heretic by Archbishop

(1528) in 1528, he introduced into Scottish theology

At length, he was summoned before a council of bishops and clergy presided over by the archbishop. There were thirteen charges, seven based on the doctrines in

At length, he was summoned before a council of bishops and clergy presided over by the archbishop. There were thirteen charges, seven based on the doctrines in

'. Students at the

For a more extensive bibliography see George M. Ella's book review.

For a more extensive bibliography see George M. Ella's book review.

Mackay's bibliography: *Knox's Hist, of the Reformation ; *Buchanan and Lindsay of Pitscottie's Histories of Scotland ; *the writings of Alexander Alesius and the records of St. Andrews and Paris are the original authorities ; *Life of Patrick Hamilton, by the Rev. Peter Lorimer, 1857, to which this article is much indebted ; *Patrick Hamilton, a poem by T. B. Johnston of Cairnie, 1873 * Rainer Haas, Franz Lambert und Patrick Hamilton in ihrer Bedeutung für die Evangelische Bewegung auf den Britischen Inseln, Marburg (theses) 1973 * The most recent biography in almost 100 years ''Patrick Hamilton – The Stephen of Scotland (1504-1528): The First Preacher and Martyr of the Scottish Reformation'', by Joe R. D. Carvalho, AD Publications, Dundee 2009.

Patrick Hamilton (1504 – 29 February 1528) was a Scottish churchman and an early Protestant Reformer in Scotland. He travelled to Europe, where he met several of the leading reformed thinkers, before returning to Scotland to preach. He was tried as a heretic by Archbishop

Patrick Hamilton (1504 – 29 February 1528) was a Scottish churchman and an early Protestant Reformer in Scotland. He travelled to Europe, where he met several of the leading reformed thinkers, before returning to Scotland to preach. He was tried as a heretic by Archbishop James Beaton

James Beaton (or Bethune) (1473–1539) was a Roman Catholic Scottish church leader, the uncle of David Cardinal Beaton and the Keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland.

Life

James Beaton was the sixth and youngest son of John Beaton of Balfour ...

, found guilty and handed over to secular authorities to be burnt at the stake in St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourt ...

as Scotland's first martyr of the Reformation.

Early life

He was the second son of SirPatrick Hamilton of Kincavil

Sir Patrick Hamilton (died 1520) was a Scottish nobleman. He was an illegitimate son of James Hamilton, 1st Lord Hamilton, and a younger brother of James Hamilton, 1st Earl of Arran.

Royal legitimation

In January 1513 James IV declared that becaus ...

and Catherine Stewart, daughter of Alexander, Duke of Albany

Alexander Stewart, Duke of Albany (7 August 1485), was a Scottish prince and the second surviving son of King James II of Scotland. He fell out with his older brother, King James III, and fled to France, where he unsuccessfully sought help. In 1 ...

, second son of James II of Scotland

James II (16 October 1430 – 3 August 1460) was King of Scots from 1437 until his death in 1460. The eldest surviving son of James I of Scotland, he succeeded to the Scottish throne at the age of six, following the assassination of his father. ...

. He was born in the diocese of Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

, probably at his father's estate of Stanehouse in Lanarkshire

Lanarkshire, also called the County of Lanark ( gd, Siorrachd Lannraig; sco, Lanrikshire), is a historic county, lieutenancy area and registration county in the central Lowlands of Scotland.

Lanarkshire is the most populous county in Scotl ...

, and was most likely educated at Linlithgow

Linlithgow (; gd, Gleann Iucha, sco, Lithgae) is a town in West Lothian, Scotland. It was historically West Lothian's county town, reflected in the county's historical name of Linlithgowshire. An ancient town, it lies in the Central Belt on a ...

. In 1517 he was appointed titular Abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the male head of a monastery in various Western religious traditions, including Christianity. The office may also be given as an honorary title to a clergyman who is not the head of a monastery. Th ...

of Fearn Abbey

Fearn Abbey – known as "The Lamp of the North" – has its origins in one of Scotland's oldest pre-Reformation church buildings. Part of the Church of Scotland and located to the southeast of Tain, Ross-shire, it continues as an activ ...

, Ross-shire

Ross-shire (; gd, Siorrachd Rois) is a historic county in the Scottish Highlands. The county borders Sutherland to the north and Inverness-shire to the south, as well as having a complex border with Cromartyshire – a county consisting ...

. The income from this position paid for him to study at the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

, where he became a Master of the Arts in 1520. It was in Paris, where Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

's writings were already exciting much discussion, that he first learnt the doctrines he would later uphold. According to sixteenth century theologian Alexander Ales

Alexander Ales or Alexander Alesius (; 23 April 150017 March 1565) was a Scottish theologian who emigrated to Germany and became a Lutheran supporter of the Augsburg Confession.

Life

Originally Alexander Alane, he was born at Edinburgh. He s ...

, Hamilton subsequently went to Leuven

Leuven (, ) or Louvain (, , ; german: link=no, Löwen ) is the capital and largest city of the province of Flemish Brabant in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is located about east of Brussels. The municipality itself comprises the historic c ...

, attracted probably by the fame of Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus (; ; English: Erasmus of Rotterdam or Erasmus;''Erasmus'' was his baptismal name, given after St. Erasmus of Formiae. ''Desiderius'' was an adopted additional name, which he used from 1496. The ''Roterodamus'' w ...

, who in 1521 had his headquarters there.

Return and flight

Returning to Scotland, Hamilton selectedSt Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourt ...

, the capital of the Catholic Church in Scotland

The Catholic Church in Scotland overseen by the Scottish Bishops' Conference, is part of the worldwide Catholic Church headed by the Pope. After being firmly established in Scotland for nearly a millennium, the Catholic Church was outlawed f ...

and of education, as his residence. On 9 June 1523 he became a member of St Leonard's College, part of the University of St Andrews

(Aien aristeuein)

, motto_lang = grc

, mottoeng = Ever to ExcelorEver to be the Best

, established =

, type = Public research university

Ancient university

, endowment ...

, and on 3 October 1524 he was admitted to its faculty of arts, where he was first a student of, and then a colleague of the Renaissance humanist

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, at first in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term ''humanist'' ( it, umanista) referred to teache ...

and logician

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

John Mair John Mair may refer to:

*John Major (philosopher)

John Major (or Mair; also known in Latin as ''Joannes Majoris'' and ''Haddingtonus Scotus''; 1467–1550) was a Scottish philosopher, theologian, and historian who was much admired in his day ...

. At the university Hamilton attained such influence that he was permitted, as precentor

A precentor is a person who helps facilitate worship. The details vary depending on the religion, denomination, and era in question. The Latin derivation is ''præcentor'', from cantor, meaning "the one who sings before" (or alternatively, "first ...

, to conduct a Solemn High Mass based on music of his own composition at the St. Andrew's Cathedral.

The reforming doctrines, however,

had obtained a firm hold on the young abbot, and he was eager to communicate them to his fellow-countrymen.

Early in 1527 the attention of James Beaton

James Beaton (or Bethune) (1473–1539) was a Roman Catholic Scottish church leader, the uncle of David Cardinal Beaton and the Keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland.

Life

James Beaton was the sixth and youngest son of John Beaton of Balfour ...

, Archbishop of St Andrews, was directed to the heretical preaching of the young priest, whereupon he ordered that Hamilton should be formally tried. Hamilton fled to Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

, enrolling himself as a student, under Franz Lambert

Franz Lambert (born 11 March 1948) is a German composer and organist. He is an avid Hammond organ player; however, he is more noted in later years for playing the Wersi range of electronic organs. During his career he has released over 100 album ...

of Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label= Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the commune had ...

, in the new University of Marburg

The Philipps University of Marburg (german: Philipps-Universität Marburg) was founded in 1527 by Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, which makes it one of Germany's oldest universities and the oldest still operating Protestant university in the wor ...

, opened on 30 May 1527 by Philip of Hesse. Among those he met there were Hermann von dem Busche, one of the contributors to the '' Epistolæ Obscurorum Virorum'', John Frith and William Tyndale

William Tyndale (; sometimes spelled ''Tynsdale'', ''Tindall'', ''Tindill'', ''Tyndall''; – ) was an English biblical scholar and linguist who became a leading figure in the Protestant Reformation in the years leading up to his execu ...

.

Late in the autumn of 1527, Fr. Hamilton returned to Scotland, speaking openly of his convictions. He went first to his brother's house at Kincavel, near Linlithgow, where he preached frequently, and, soon afterwards, he renounced clerical celibacy

Clerical celibacy is the requirement in certain religions that some or all members of the clergy be unmarried. Clerical celibacy also requires abstention from deliberately indulging in sexual thoughts and behavior outside of marriage, because thes ...

and married a young lady of noble rank; her name is unrecorded. David Beaton

David Beaton (also Beton or Bethune; 29 May 1546) was Archbishop of St Andrews and the last Scottish cardinal prior to the Reformation.

Career

Cardinal Beaton was the sixth and youngest son of eleven children of John Beaton (Bethune) of Bal ...

, the Abbot of Arbroath, avoiding open violence through fear of Hamilton's powerful protectors, invited him to a conference at St Andrews. The Young minister, predicting that he was going to "confirm the pious in the true doctrine" by his death, accepted the invitation, and for nearly a month was allowed to preach and to debate.

With the publication of ''Patrick's Places''''Patrick's Places''(1528) in 1528, he introduced into Scottish theology

Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

's emphasis of the distinction of Law and Gospel

In Protestant Christianity, the relationship between Law and Gospel—God's Law and the Gospel of Jesus Christ—is a major topic in Lutheran and Reformed theology. In these religious traditions, the distinction between the doctrines of L ...

.

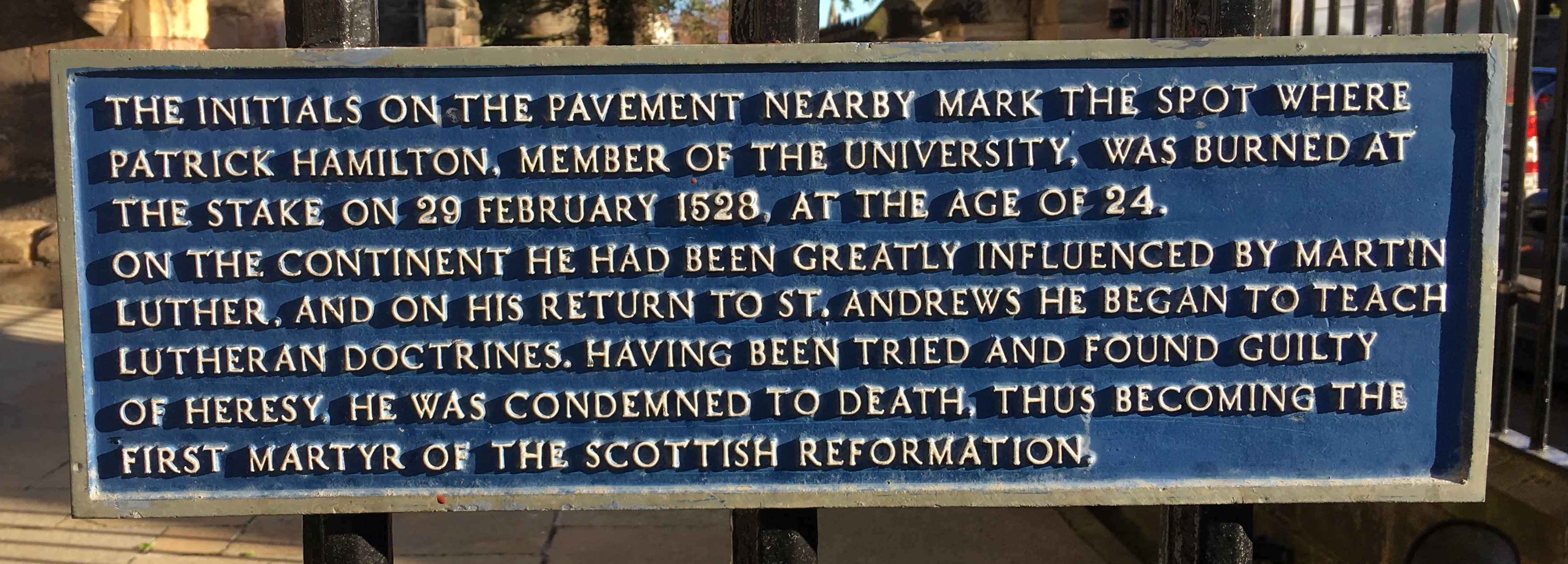

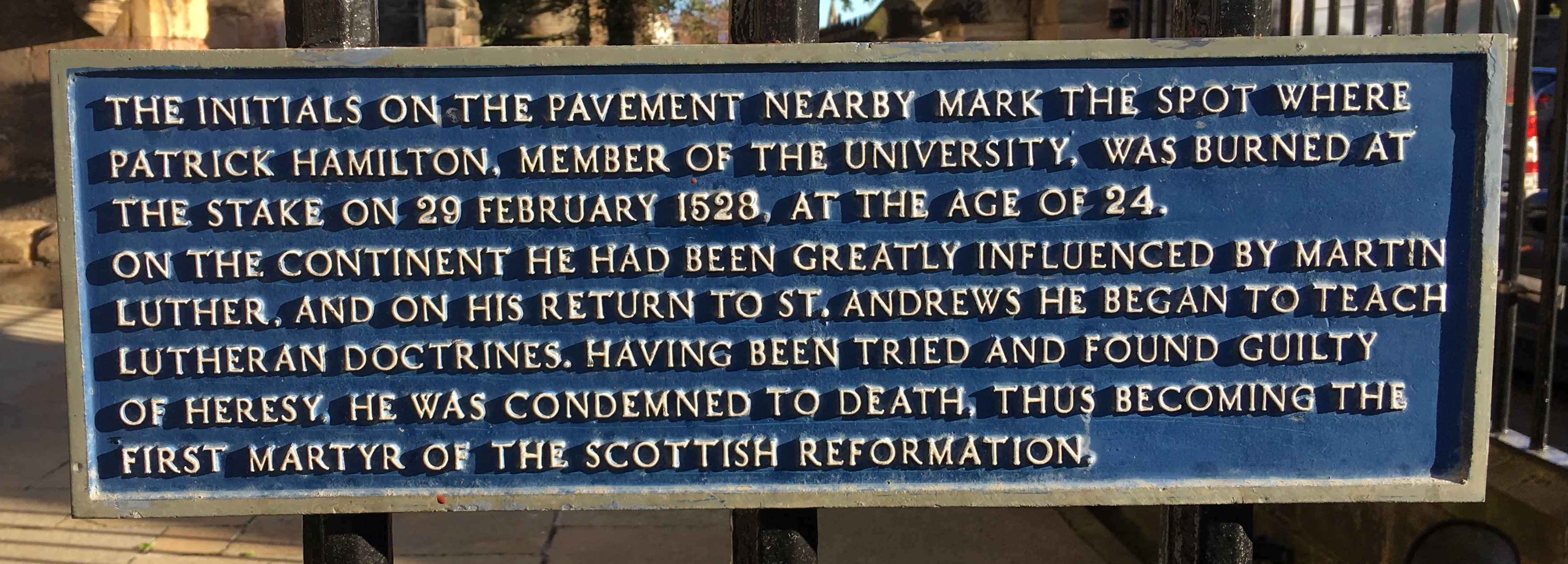

Trial and execution

At length, he was summoned before a council of bishops and clergy presided over by the archbishop. There were thirteen charges, seven based on the doctrines in

At length, he was summoned before a council of bishops and clergy presided over by the archbishop. There were thirteen charges, seven based on the doctrines in Philip Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the L ...

's '' Loci Communes'', the first theological exposition of Martin Luther's scriptural study and teachings in 1521. On examination Hamilton expressed a belief in their truth, and the council sentenced him to death on all thirteen charges. Hamilton was seized, and allegedly surrendered to the soldiery based on an assurance that he would be restored to his friends without injury. However, after a debate with Friar Campbell, the council handed him over to the secular power, to be burnt at the stake

Death by burning (also known as immolation) is an execution and murder method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment f ...

outside the front entrance to St Salvator's Chapel in St Andrews. The sentence was carried out on the same day to preclude any attempted rescue by friends. He burnt from noon to 6 p.m. and his last words were "Lord Jesus, receive my spirit". The spot is today marked with a monogram

A monogram is a motif made by overlapping or combining two or more letters or other graphemes to form one symbol. Monograms are often made by combining the initials of an individual or a company, used as recognizable symbols or logos. A series ...

of his initials set into the cobblestones of the pavement of North Street.

Legacy

Hamilton's execution attracted more interest than ever before toLutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

and greatly contributed to the Reformation in Scotland

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Scotland broke with the Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterian in its outlook. It was part of the wider European Protestant Re ...

. It was said that the "reek of Master Patrick Hamilton infected as many as it blew upon". Hamilton's fortitude during his execution persuaded Alexander Ales

Alexander Ales or Alexander Alesius (; 23 April 150017 March 1565) was a Scottish theologian who emigrated to Germany and became a Lutheran supporter of the Augsburg Confession.

Life

Originally Alexander Alane, he was born at Edinburgh. He s ...

, who had been appointed to convince Hamilton of his errors, to enter into the Lutheran Church. His martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an externa ...

dom is unusual in that he was almost alone in Scotland during the Lutheran stage of the Reformation. His only known writings, based upon ''Loci communes'' and known as "Patrick's Places", echoed the doctrine of justification by faith and the contrast between the gospel and the law in a series of clear-cut propositions.'"Patrickes Places"' was not Hamilton's own title, but was given in the translation into English by John Fryth in 1564, and are presented in Book 8 of the 1570 edition of John Foxe's "Acts and Monuments".'. Students at the

University of St Andrews

(Aien aristeuein)

, motto_lang = grc

, mottoeng = Ever to ExcelorEver to be the Best

, established =

, type = Public research university

Ancient university

, endowment ...

traditionally avoid stepping on the monogram of Hamilton's initials outside St Salvator's Chapel for fear of being cursed and failing their final exams. To lift the curse students may participate in the annual May dip where they traditionally run into the North Sea at 05.00 to wash away their sins and bad luck.

A school in Auckland, New Zealand called 'Saint Kentigern College

Saint Kentigern College is a private co-educational Presbyterian secondary school in the suburb of Pakuranga on the eastern side of Auckland, New Zealand, beside the Tamaki Estuary. It is operated by the Saint Kentigern Trust Board which also ...

' has a house named after Patrick Hamilton

Katherine Hamilton

Patrick's sister, Katherine Hamilton, was the wife of the Captain ofDunbar Castle

Dunbar Castle was one of the strongest fortresses in Scotland, situated in a prominent position overlooking the harbour of the town of Dunbar, in East Lothian. Several fortifications were built successively on the site, near the English-Scotti ...

and also a committed Protestant. In March 1539 she was forced in exile to Berwick upon Tweed for her beliefs. She had been in England before and met the Queen, Jane Seymour

Jane Seymour (c. 150824 October 1537) was Queen of England as the third wife of King Henry VIII of England from their marriage on 30 May 1536 until her death the next year. She became queen following the execution of Henry's second wife, Anne ...

.

According to the historian John Spottiswood

John Spottiswoode (Spottiswood, Spotiswood, Spotiswoode or Spotswood) (1565 – 26 November 1639) was an Archbishop of St Andrews, Primate of All Scotland, Lord Chancellor, and historian of Scotland.

Life

He was born in 1565 at Greenbank in ...

, Katherine was brought to trial for heresy before James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV and Margaret Tudor, and du ...

at Holyroodhouse in 1534, and her other brother James Hamilton of Livingston fled. The King was impressed by her conviction shown in her short answer to the prosecutor. He laughed and spoke to her privately, convincing her to abandon her profession of faith. The other accused also recanted for the time.Spottiswood, John, ''The History of the Church of Scotland'', (1668), Bk. 2, pp.65-66

Bibliography

For a more extensive bibliography see George M. Ella's book review.

For a more extensive bibliography see George M. Ella's book review.

Mackay's bibliography: *Knox's Hist, of the Reformation ; *Buchanan and Lindsay of Pitscottie's Histories of Scotland ; *the writings of Alexander Alesius and the records of St. Andrews and Paris are the original authorities ; *Life of Patrick Hamilton, by the Rev. Peter Lorimer, 1857, to which this article is much indebted ; *Patrick Hamilton, a poem by T. B. Johnston of Cairnie, 1873 * Rainer Haas, Franz Lambert und Patrick Hamilton in ihrer Bedeutung für die Evangelische Bewegung auf den Britischen Inseln, Marburg (theses) 1973 * The most recent biography in almost 100 years ''Patrick Hamilton – The Stephen of Scotland (1504-1528): The First Preacher and Martyr of the Scottish Reformation'', by Joe R. D. Carvalho, AD Publications, Dundee 2009.

See also

*Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process by which Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke with the Pope, Papacy and developed a predominantly Calvinist national Church of Scotland, Kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterianism, Presbyterian in ...

* John Ogilvie (saint)

John Ogilvie (1580 – 10 March 1615) was a Scottish Jesuit martyr. For his work as a priest in service to a persecuted Roman Catholic community in 17th century Scotland, and in being hanged for his faith, he became the only post-Reformation ...

* List of Protestant martyrs of the Scottish Reformation

References

;Citations ;Sources * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Attribution *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Hamilton, Patrick 1504 births 1528 deaths People executed for heresy Executed Scottish people Alumni of the University of St Andrews University of Paris alumni 16th-century Scottish clergy Scottish abbots 16th-century Protestant religious leaders 16th-century Protestant martyrs People from Linlithgow People from South Lanarkshire People executed by the Kingdom of Scotland by burning 16th-century executions by Scotland Scottish Reformation Protestant martyrs of Scotland