Partial Test Ban Treaty on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) is the abbreviated name of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water, which prohibited all test detonations of

Much of the stimulus for the treaty was increasing public unease about radioactive fallout as a result of above-ground or underwater nuclear testing, particularly given the increasing power of nuclear devices, as well as concern about the general environmental damage caused by testing. In 1952–53, the US and Soviet Union detonated their first

Much of the stimulus for the treaty was increasing public unease about radioactive fallout as a result of above-ground or underwater nuclear testing, particularly given the increasing power of nuclear devices, as well as concern about the general environmental damage caused by testing. In 1952–53, the US and Soviet Union detonated their first

The Soviet Union dismissed the Baruch Plan as a US attempt to secure its nuclear dominance, and called for the US to halt weapons production and release technical information on its program. The Acheson–Lilienthal paper and Baruch Plan would serve as the basis for US policy into the 1950s. Between 1947 and 1954, the US and Soviet Union discussed their demands within the United Nations Commission for Conventional Disarmament. A series of events in 1954, including the Castle Bravo test and spread of fallout from a Soviet test over Japan, redirected the international discussion on nuclear policy. Additionally, by 1954, both US and Soviet Union had assembled large nuclear stockpiles, reducing hopes of complete disarmament. In the early years of the

The Soviet Union dismissed the Baruch Plan as a US attempt to secure its nuclear dominance, and called for the US to halt weapons production and release technical information on its program. The Acheson–Lilienthal paper and Baruch Plan would serve as the basis for US policy into the 1950s. Between 1947 and 1954, the US and Soviet Union discussed their demands within the United Nations Commission for Conventional Disarmament. A series of events in 1954, including the Castle Bravo test and spread of fallout from a Soviet test over Japan, redirected the international discussion on nuclear policy. Additionally, by 1954, both US and Soviet Union had assembled large nuclear stockpiles, reducing hopes of complete disarmament. In the early years of the

The British governments of 1954–58 (under

The British governments of 1954–58 (under  In the spring of 1957, the US National Security Council had explored including a one-year test moratorium and a "cut-off" of fissionable-material production in a "partial" disarmament plan. The British government, then led by Macmillan, had yet to fully endorse a test ban. Accordingly, it pushed the US to demand that the production cut-off be closely timed with the testing moratorium, betting that the Soviet Union would reject this. London also encouraged the US to delay its disarmament plan, in part by moving the start of the moratorium back to November 1958. At the same time, Macmillan linked British support for a test ban to a revision of the

In the spring of 1957, the US National Security Council had explored including a one-year test moratorium and a "cut-off" of fissionable-material production in a "partial" disarmament plan. The British government, then led by Macmillan, had yet to fully endorse a test ban. Accordingly, it pushed the US to demand that the production cut-off be closely timed with the testing moratorium, betting that the Soviet Union would reject this. London also encouraged the US to delay its disarmament plan, in part by moving the start of the moratorium back to November 1958. At the same time, Macmillan linked British support for a test ban to a revision of the

The technical findings, released on 30 August 1958 in a report drafted by the Soviet delegation, were endorsed by the US and UK, which proposed that they serve as the basis for test-ban and international-control negotiations. However, the experts' report failed to address precisely who would do the monitoring and when on-site inspections—a US demand and Soviet concern—would be permitted. The experts also deemed detection of outer-space tests (tests more than above the earth's surface) to be impractical. Additionally, the size of the Geneva System may have rendered it too expensive to be put into effect. The 30 August report, which contained details on these limitations, received significantly less public attention than the 21 August communiqué.

Nevertheless, pleased by the findings, the Eisenhower administration proposed negotiations on a permanent test ban and announced it would self-impose a year-long testing moratorium if Britain and the Soviet Union did the same. This decision amounted to a victory for John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles (then the

The technical findings, released on 30 August 1958 in a report drafted by the Soviet delegation, were endorsed by the US and UK, which proposed that they serve as the basis for test-ban and international-control negotiations. However, the experts' report failed to address precisely who would do the monitoring and when on-site inspections—a US demand and Soviet concern—would be permitted. The experts also deemed detection of outer-space tests (tests more than above the earth's surface) to be impractical. Additionally, the size of the Geneva System may have rendered it too expensive to be put into effect. The 30 August report, which contained details on these limitations, received significantly less public attention than the 21 August communiqué.

Nevertheless, pleased by the findings, the Eisenhower administration proposed negotiations on a permanent test ban and announced it would self-impose a year-long testing moratorium if Britain and the Soviet Union did the same. This decision amounted to a victory for John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles (then the

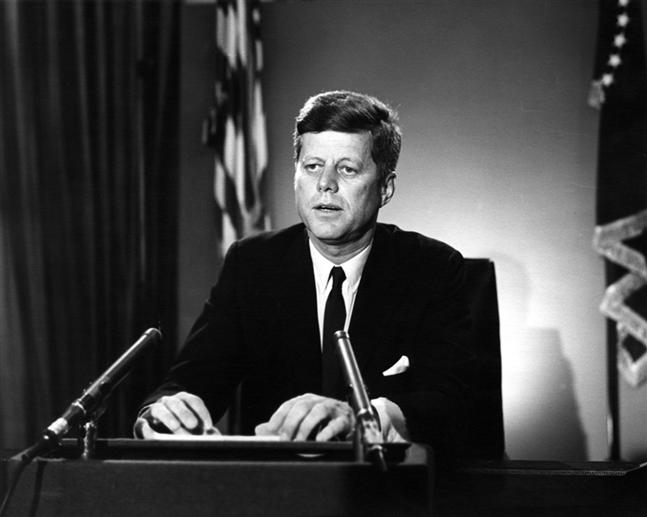

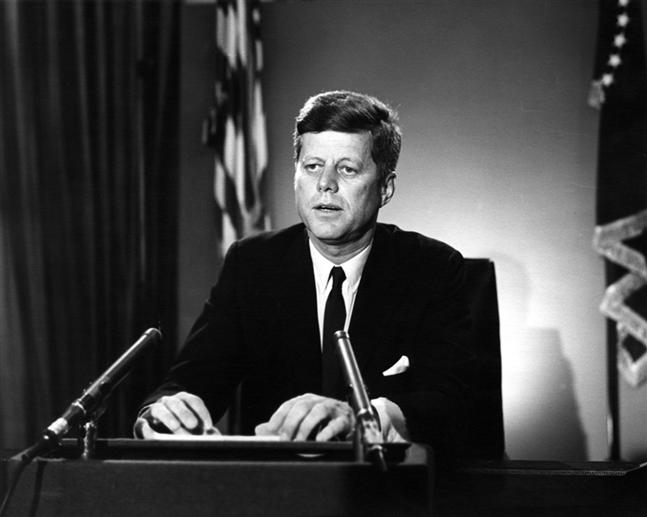

Upon assuming the presidency in January 1961, John F. Kennedy was committed to pursuing a comprehensive test ban and ordered a review of the American negotiating position in an effort to accelerate languishing talks, believing Eisenhower's approach to have been "insufficient." In making his case for a test ban, Kennedy drew a direct link between continued testing and nuclear proliferation, calling it the "'Nth-country' problem." While a candidate, Kennedy had argued, "For once

Upon assuming the presidency in January 1961, John F. Kennedy was committed to pursuing a comprehensive test ban and ordered a review of the American negotiating position in an effort to accelerate languishing talks, believing Eisenhower's approach to have been "insufficient." In making his case for a test ban, Kennedy drew a direct link between continued testing and nuclear proliferation, calling it the "'Nth-country' problem." While a candidate, Kennedy had argued, "For once

In December 1961, Macmillan met with Kennedy in

In December 1961, Macmillan met with Kennedy in

The agreement was initialed on 25 July 1963, just 10 days after negotiations commenced. The following day, Kennedy delivered a 26-minute televised address on the agreement, declaring that since the invention of nuclear weapons, "all mankind has been struggling to escape from the darkening prospect of mass destruction on earth ... Yesterday a shaft of light cut into the darkness." Kennedy expressed hope that the test ban would be the first step towards broader rapprochement, limit nuclear fallout, restrict nuclear proliferation, and slow the arms race in such a way that fortifies US security. Kennedy concluded his address in reference to a Chinese

The agreement was initialed on 25 July 1963, just 10 days after negotiations commenced. The following day, Kennedy delivered a 26-minute televised address on the agreement, declaring that since the invention of nuclear weapons, "all mankind has been struggling to escape from the darkening prospect of mass destruction on earth ... Yesterday a shaft of light cut into the darkness." Kennedy expressed hope that the test ban would be the first step towards broader rapprochement, limit nuclear fallout, restrict nuclear proliferation, and slow the arms race in such a way that fortifies US security. Kennedy concluded his address in reference to a Chinese

Administration testimony sought to counteract these arguments. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara announced his "unequivocal support" for the treaty before the Foreign Relations Committee, arguing that US nuclear forces were secure and clearly superior to those of the Soviet Union, and that any major Soviet tests would be detected. Glenn T. Seaborg, the chairman of the AEC, also gave his support to the treaty in testimony, as did Harold Brown, the Department of Defense's lead scientist, and

Administration testimony sought to counteract these arguments. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara announced his "unequivocal support" for the treaty before the Foreign Relations Committee, arguing that US nuclear forces were secure and clearly superior to those of the Soviet Union, and that any major Soviet tests would be detected. Glenn T. Seaborg, the chairman of the AEC, also gave his support to the treaty in testimony, as did Harold Brown, the Department of Defense's lead scientist, and

nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

s except for those conducted underground. It is also abbreviated as the Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT) and Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (NTBT), though the latter may also refer to the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty

The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) is a multilateral treaty to ban nuclear weapons test explosions and any other nuclear explosions, for both civilian and military purposes, in all environments. It was adopted by the United Nati ...

(CTBT), which succeeded the PTBT for ratifying parties.

Negotiations initially focused on a comprehensive ban, but that was abandoned because of technical questions surrounding the detection of underground tests and Soviet concerns over the intrusiveness of proposed verification methods. The impetus for the test ban was provided by rising public anxiety over the magnitude of nuclear tests, particularly tests of new thermonuclear weapons (hydrogen bombs), and the resulting nuclear fallout

Nuclear fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and the shock wave has passed. It commonly refers to the radioac ...

. A test ban was also seen as a means of slowing nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons, fissionable material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information to nations not recognized as " Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Wea ...

and the nuclear arms race

The nuclear arms race was an arms race competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War. During this same period, in addition to the American and Soviet nuc ...

. Though the PTBT did not halt proliferation or the arms race, its enactment did coincide with a substantial decline in the concentration of radioactive particles in the atmosphere.

The PTBT was signed by the governments of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

, and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

on 5 August 1963 before it was opened for signature by other countries. The treaty formally went into effect on 10 October 1963. Since then, 123 other states have become party to the treaty. Ten states have signed but not ratified the treaty.

Background

Much of the stimulus for the treaty was increasing public unease about radioactive fallout as a result of above-ground or underwater nuclear testing, particularly given the increasing power of nuclear devices, as well as concern about the general environmental damage caused by testing. In 1952–53, the US and Soviet Union detonated their first

Much of the stimulus for the treaty was increasing public unease about radioactive fallout as a result of above-ground or underwater nuclear testing, particularly given the increasing power of nuclear devices, as well as concern about the general environmental damage caused by testing. In 1952–53, the US and Soviet Union detonated their first thermonuclear weapon

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lo ...

s (hydrogen bombs), far more powerful than the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

s tested and deployed since 1945

1945 marked the end of World War II and the fall of Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan. It is also the only year in which Nuclear weapon, nuclear weapons Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, have been used in combat.

Events

Below, ...

. In 1954, the US Castle Bravo

Castle Bravo was the first in a series of high-yield thermonuclear weapon design tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands, as part of '' Operation Castle''. Detonated on March 1, 1954, the device was the most powerful ...

test at Bikini Atoll

Bikini Atoll ( or ; Marshallese: , , meaning "coconut place"), sometimes known as Eschscholtz Atoll between the 1800s and 1946 is a coral reef in the Marshall Islands consisting of 23 islands surrounding a central lagoon. After the Seco ...

(part of Operation Castle) had a yield of 15 megatons of TNT, more than doubling the expected yield. The Castle Bravo test resulted in the worst radiological event in US history as radioactive particles spread over more than , affected inhabited areas (including Rongelap Atoll and Utirik Atoll

Utirik Atoll or Utrik Atoll ( Marshallese: , ) is a coral atoll of 10 islands in the Pacific Ocean, and forms a legislative district of the Ratak Chain of the Marshall Islands. Its total land area is only , but it encloses a lagoon with an area ...

), and sickened Japanese fishermen aboard the '' Lucky Dragon'' upon whom "ashes of death" had rained. In the same year, a Soviet test sent radioactive particles over Japan. Around the same time, victims of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima visited the US for medical care, which attracted significant public attention. In 1961, the Soviet Union tested the Tsar Bomba

The Tsar Bomba () ( code name: ''Ivan'' or ''Vanya''), also known by the alphanumerical designation "AN602", was a thermonuclear aerial bomb, and the most powerful nuclear weapon ever created and tested. Overall, the Soviet physicist Andrei ...

, which had a yield of 50 megatons and remains the most powerful man-made explosion in history, though due to a highly efficient detonation fallout was relatively limited. Between 1951 and 1958, the US conducted 166 atmospheric tests, the Soviet Union conducted 82, and Britain conducted 21; only 22 underground tests were conducted in this period (all by the US).

Negotiations

Early efforts

In 1945, Britain and Canada made an early call for an international discussion on controlling atomic power. At the time, the US had yet to formulate a cohesive policy or strategy on nuclear weapons. Taking advantage of this wasVannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush ( ; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almost all warti ...

, who had initiated and administered the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, but nevertheless had a long-term policy goal of banning on nuclear weapons production. As a first step in this direction, Bush proposed an international agency dedicated to nuclear control. Bush unsuccessfully argued in 1952 that the US pursue a test ban agreement with the Soviet Union before testing its first thermonuclear weapon, but his interest in international controls was echoed in the 1946 Acheson–Lilienthal Report

The ''Report on the International Control of Atomic Energy'' was written by a committee chaired by Dean Acheson and David Lilienthal in 1946 and is generally known as the Acheson–Lilienthal Report or Plan. The report was an important American ...

, which had been commissioned by President Harry S. Truman to help construct US nuclear weapons policy. J. Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is oft ...

, who had led Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory (often shortened as Los Alamos and LANL) is one of the sixteen research and development laboratories of the United States Department of Energy (DOE), located a short distance northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, ...

during the Manhattan Project, exerted significant influence over the report, particularly in its recommendation of an international body that would control production of and research on the world's supply of uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

and thorium

Thorium is a weakly radioactive metallic chemical element with the symbol Th and atomic number 90. Thorium is silvery and tarnishes black when it is exposed to air, forming thorium dioxide; it is moderately soft and malleable and has a high ...

. A version of the Acheson-Lilienthal plan was presented to the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission The United Nations Atomic Energy Commission (UNAEC) was founded on 24 January 1946 by the very first resolution of the United Nations General Assembly "to deal with the problems raised by the discovery of atomic energy."

The General Assembly asked ...

as the Baruch Plan

The Baruch Plan was a proposal by the United States government, written largely by Bernard Baruch but based on the Acheson–Lilienthal Report, to the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission (UNAEC) during its first meeting in June 1946. The United ...

in June 1946. The Baruch Plan proposed that an International Atomic Development Authority would control all research on and material and equipment involved in the production of atomic energy. Though Dwight D. Eisenhower, then the Chief of Staff of the United States Army

The chief of staff of the Army (CSA) is a statutory position in the United States Army held by a general officer. As the highest-ranking officer assigned to serve in the Department of the Army, the chief is the principal military advisor and ...

, was not a significant figure in the Truman administration on nuclear questions, he did support Truman's nuclear control policy, including the Baruch Plan's provision for an international control agency, provided that the control system was accompanied by "a system of free and complete inspection."

The Soviet Union dismissed the Baruch Plan as a US attempt to secure its nuclear dominance, and called for the US to halt weapons production and release technical information on its program. The Acheson–Lilienthal paper and Baruch Plan would serve as the basis for US policy into the 1950s. Between 1947 and 1954, the US and Soviet Union discussed their demands within the United Nations Commission for Conventional Disarmament. A series of events in 1954, including the Castle Bravo test and spread of fallout from a Soviet test over Japan, redirected the international discussion on nuclear policy. Additionally, by 1954, both US and Soviet Union had assembled large nuclear stockpiles, reducing hopes of complete disarmament. In the early years of the

The Soviet Union dismissed the Baruch Plan as a US attempt to secure its nuclear dominance, and called for the US to halt weapons production and release technical information on its program. The Acheson–Lilienthal paper and Baruch Plan would serve as the basis for US policy into the 1950s. Between 1947 and 1954, the US and Soviet Union discussed their demands within the United Nations Commission for Conventional Disarmament. A series of events in 1954, including the Castle Bravo test and spread of fallout from a Soviet test over Japan, redirected the international discussion on nuclear policy. Additionally, by 1954, both US and Soviet Union had assembled large nuclear stockpiles, reducing hopes of complete disarmament. In the early years of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

, the US approach to nuclear control reflected a strain between an interest in controlling nuclear weapons and a belief that dominance in the nuclear arena, particularly given the size of Soviet conventional forces, was critical to US security. Interest in nuclear control and efforts to stall proliferation of weapons to other states grew as the Soviet Union's nuclear capabilities increased.

After Castle Bravo: 1954–1958

In 1954, just weeks after the Castle Bravo test, Indian prime ministerJawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India du ...

made the first call for a "standstill agreement" on nuclear testing, who saw a testing moratorium as a stepping stone to more comprehensive arms control agreements. In the same year, the British Labour Party

The Labour Party is a political party in the United Kingdom that has been described as an alliance of social democrats, democratic socialists and trade unionists. The Labour Party sits on the centre-left of the political spectrum. In all ...

, then led by Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

, called on the UN to ban testing of thermonuclear weapons. 1955 marks the beginning of test-ban negotiations, as Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

first proposed talks on the subject in February 1955. On 10 May 1955, the Soviet Union proposed a test ban before the UN Disarmament Commission's "Committee of Five" (Britain, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the Soviet Union, and the US). This proposal, which closely reflected a prior Anglo-French proposal, was initially part of a comprehensive disarmament proposal meant to reduce conventional arms levels and eliminate nuclear weapons. Despite the closeness of the Soviet proposal to earlier Western proposals, the US reversed its position on the provisions and rejected the Soviet offer "in the absence of more general control agreements," including limits on the production of fissionable material and protections against a surprise nuclear strike. The May 1955 proposal is now seen as evidence of Khrushchev's "new approach" to foreign policy, as Khrushchev sought to mend relations with the West. The proposal would serve as the basis of the Soviet negotiating position through 1957.

Eisenhower had supported nuclear testing after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. In 1947, he rejected arguments by Stafford L. Warren

Stafford Leak Warren (July 19, 1896 - July 26, 1981) was an American physician and radiologist who was a pioneer in the field of nuclear medicine and best known for his invention of the mammogram. Warren developed the technique of producing ster ...

, the Manhattan Project's chief physician, concerning the detrimental health effects of atmospheric testing, agreeing instead with James Bryant Conant

James Bryant Conant (March 26, 1893 – February 11, 1978) was an American chemist, a transformative President of Harvard University, and the first U.S. Ambassador to West Germany. Conant obtained a Ph.D. in Chemistry from Harvard in 1916 ...

, a chemist and participant in the Manhattan Project, who was skeptical of Warren's then-theoretical claims. Warren's arguments were lent credence in the scientific community and public by the Castle Bravo test of 1954. Eisenhower, as president, first explicitly expressed interest in a comprehensive test ban that year, arguing before the National Security Council

A national security council (NSC) is usually an executive branch governmental body responsible for coordinating policy on national security issues and advising chief executives on matters related to national security. An NSC is often headed by a n ...

, "We could put he Russians

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

on the spot if we accepted a moratorium ... Everybody seems to think that we're skunks, saber-rattlers and warmongers. We ought not miss any chance to make clear our peaceful objectives." Then-Secretary of State John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles (, ; February 25, 1888 – May 24, 1959) was an American diplomat, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. He served as United States Secretary of State under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1959 and was briefly ...

had responded skeptically to the limited arms-control suggestion of Nehru, whose proposal for a test ban was discarded by the National Security Council for being "not practical." Harold Stassen, Eisenhower's special assistant for disarmament, argued that the US should prioritize a test ban as a first step towards comprehensive arms control, conditional on the Soviet Union accepting on-site inspections, over full disarmament. Stassen's suggestion was dismissed by others in the administration over fears that the Soviet Union would be able to conduct secret tests. On the advice of Dulles, Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) chairman Lewis Strauss, and Secretary of Defense Charles Erwin Wilson

Charles Erwin Wilson (July 18, 1890 – September 26, 1961) was an American engineer and businessman who served as United States Secretary of Defense from 1953 to 1957 under President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Known as "Engine Charlie", he was pre ...

, Eisenhower rejected the idea of considering a test ban outside general disarmament efforts. During the 1952

Events January–February

* January 26 – Black Saturday in Egypt: Rioters burn Cairo's central business district, targeting British and upper-class Egyptian businesses.

* February 6

** Princess Elizabeth, Duchess of Edinburgh, becomes m ...

and 1956

Events

January

* January 1 – The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium ends in Sudan.

* January 8 – Operation Auca: Five U.S. evangelical Christian missionaries, Nate Saint, Roger Youderian, Ed McCully, Jim Elliot and Pete Fleming, are kille ...

presidential elections, Eisenhower fended off challenger Adlai Stevenson, who ran in large part on support for a test ban.

The British governments of 1954–58 (under

The British governments of 1954–58 (under Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid promo ...

, and Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was a British Conservative statesman and politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Caricatured as " Supermac", ...

) also quietly resisted a test ban, despite the British public favoring a deal, until the US Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washin ...

approved expanded nuclear collaboration in 1958 and until after Britain had tested its first hydrogen bombs. In their view, testing was necessary if the UK nuclear program were to continue to develop. This opposition was tempered by concern that resistance to a test ban might lead the US and Soviet Union to pursue an agreement without Britain having any say in the matter.

Members of the Soviet military–industrial complex

The expression military–industrial complex (MIC) describes the relationship between a country's military and the defense industry that supplies it, seen together as a vested interest which influences public policy. A driving factor behind the ...

also opposed a test ban, though some scientists, including Igor Kurchatov

Igor Vasil'evich Kurchatov (russian: Игорь Васильевич Курчатов; 12 January 1903 – 7 February 1960), was a Soviet physicist who played a central role in organizing and directing the former Soviet program of nuclear weapo ...

, were supportive of antinuclear efforts. France, which was in the midst of developing its own nuclear weapon, also firmly opposed a test ban in the late 1950s.

The proliferation of thermonuclear weapons coincided with a rise in public concern about nuclear fallout

Nuclear fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and the shock wave has passed. It commonly refers to the radioac ...

debris contaminating food sources, particularly the threat of high levels of strontium-90

Strontium-90 () is a radioactive isotope of strontium produced by nuclear fission, with a half-life of 28.8 years. It undergoes β− decay into yttrium-90, with a decay energy of 0.546 MeV. Strontium-90 has applications in medicine and ...

in milk (see the Baby Tooth Survey). This survey was a scientist and citizen led campaign which used "modern media advocacy techniques to communicate complex issues" to inform public discourse. Its research findings confirmed a significant build-up of strontium-90 in bones of babies and helped galvanise public support for a ban on atmospheric nuclear testing in the US. Lewis Strauss and Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

, dubbed the "father of the hydrogen bomb," both sought to tamp down on these fears, arguing that fallout t the dose levels of US exposurewere fairly harmless and that a test ban would enable the Soviet Union to surpass the US in nuclear capabilities. Teller also suggested that testing was necessary to develop nuclear weapons that produced less fallout. Support in the US public for a test ban to continue to grow from 20% in 1954 to 63% by 1957. Moreover, widespread antinuclear protests were organized and led by theologian and Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolo ...

laureate Albert Schweitzer

Ludwig Philipp Albert Schweitzer (; 14 January 1875 – 4 September 1965) was an Alsatian-German/French polymath. He was a theologian, organist, musicologist, writer, humanitarian, philosopher, and physician. A Lutheran minister, Schweit ...

, whose appeals were endorsed by Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

, and Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topi ...

, the latter of whom organized an anti-test petition signed by more than 9,000 scientists across 43 countries (including the infirm and elderly Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

).

The AEC would eventually concede, as well, that even low levels of radiation were harmful. It was a combination of rising public support for a test ban and the shock of the 1957 Soviet ''Sputnik

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for ...

'' launch that encouraged Eisenhower to take steps towards a test ban in 1958.

There was also increased environmental concern in the Soviet Union. In the mid-1950s, Soviet scientists began taking regular radiation readings near Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, and Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

and collected data on the prevalence of strontium-90, which indicated that strontium-90 levels in western Russia approximately matched those in the eastern US. Rising Soviet concern was punctuated in September 1957 by the Kyshtym disaster, which forced the evacuation of 10,000 people after an explosion at a nuclear plant. Around the same time, 219 Soviet scientists signed Pauling's antinuclear petition. Soviet political elites did not share the concerns of others in the Soviet Union. However; Kurchatov unsuccessfully called on Khrushchev to halt testing in 1958.

On 14 June 1957, following Eisenhower's suggestion that existing detection measures were inadequate to ensure compliance, the Soviet Union put forth a plan for a two-to-three-year testing moratorium. The moratorium would be overseen by an international commission reliant on national monitoring stations, but, importantly, would involve no on-the-ground inspections. Eisenhower initially saw the deal as favorable, but eventually came to see otherwise. In particular, Strauss and Teller, as well as Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation fo ...

and Mark Muir Mills, protested the offer. At a meeting with Eisenhower in the White House, the group argued that testing was necessary for the US to eventually develop bombs that produced no fallout ("clean bombs"). The group repeated the oft-cited fact, which was supported by Freeman Dyson

Freeman John Dyson (15 December 1923 – 28 February 2020) was an English-American theoretical physicist and mathematician known for his works in quantum field theory, astrophysics, random matrices, mathematical formulation of quantum m ...

, that the Soviet Union could conduct secret nuclear tests. In 1958, at the request of Igor Kurchatov, Soviet nuclear physicist and weapons designer Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov ( rus, Андрей Дмитриевич Сахаров, p=ɐnˈdrʲej ˈdmʲitrʲɪjevʲɪtɕ ˈsaxərəf; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident, nobel laureate and activist for n ...

published a pair of widely circulated academic papers challenging the claim of Teller and others that a clean, fallout-free nuclear bomb could be developed, due to the formation of carbon-14

Carbon-14, C-14, or radiocarbon, is a radioactive isotope of carbon with an atomic nucleus containing 6 protons and 8 neutrons. Its presence in organic materials is the basis of the radiocarbon dating method pioneered by Willard Libby and co ...

when nuclear devices are detonated in the air. A one-megaton clean bomb, Sakharov estimated, would cause 6,600 deaths over 8,000 years, figures derived largely from estimates on the quantity of carbon-14

Carbon-14, C-14, or radiocarbon, is a radioactive isotope of carbon with an atomic nucleus containing 6 protons and 8 neutrons. Its presence in organic materials is the basis of the radiocarbon dating method pioneered by Willard Libby and co ...

generated from atmospheric nitrogen and the contemporary risk models at the time, along with the assumption that the world population is "thirty billion persons" in a few thousand years. In 1961, Sakharov was part of the design team for a 50 megaton "clean bomb", which has become known as the Tsar Bomba

The Tsar Bomba () ( code name: ''Ivan'' or ''Vanya''), also known by the alphanumerical designation "AN602", was a thermonuclear aerial bomb, and the most powerful nuclear weapon ever created and tested. Overall, the Soviet physicist Andrei ...

, detonated over the island of Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya (, also , ; rus, Но́вая Земля́, p=ˈnovəjə zʲɪmˈlʲa, ) is an archipelago in northern Russia. It is situated in the Arctic Ocean, in the extreme northeast of Europe, with Cape Flissingsky, on the northern island, ...

.

In the spring of 1957, the US National Security Council had explored including a one-year test moratorium and a "cut-off" of fissionable-material production in a "partial" disarmament plan. The British government, then led by Macmillan, had yet to fully endorse a test ban. Accordingly, it pushed the US to demand that the production cut-off be closely timed with the testing moratorium, betting that the Soviet Union would reject this. London also encouraged the US to delay its disarmament plan, in part by moving the start of the moratorium back to November 1958. At the same time, Macmillan linked British support for a test ban to a revision of the

In the spring of 1957, the US National Security Council had explored including a one-year test moratorium and a "cut-off" of fissionable-material production in a "partial" disarmament plan. The British government, then led by Macmillan, had yet to fully endorse a test ban. Accordingly, it pushed the US to demand that the production cut-off be closely timed with the testing moratorium, betting that the Soviet Union would reject this. London also encouraged the US to delay its disarmament plan, in part by moving the start of the moratorium back to November 1958. At the same time, Macmillan linked British support for a test ban to a revision of the Atomic Energy Act of 1946

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (McMahon Act) determined how the United States would control and manage the nuclear technology it had jointly developed with its World War II allies, the United Kingdom and Canada. Most significantly, the Act ru ...

(McMahon Act), which prohibited sharing of nuclear information with foreign governments. Eisenhower, eager to mend ties with Britain following the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

of 1956, was receptive to Macmillan's conditions, but the AEC and the congressional Joint Committee on Atomic Energy were firmly opposed. It was not until after ''Sputnik'' in late 1957 that Eisenhower quickly moved to expand nuclear collaboration with the UK via presidential directives and the establishment of bilateral committees on nuclear matters. In early 1958, Eisenhower publicly stated that amendments to the McMahon Act were a necessary condition of a test ban, framing the policy shift in the context of US commitment to its NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

allies.

In August 1957, the US assented to a two-year testing moratorium proposed by the Soviet Union, but required that it be linked to restrictions on the production of fissionable material with military uses, a condition that the Soviet Union rejected. While Eisenhower insisted on linking a test ban to a broader disarmament effort (e.g., the production cut-off), Moscow insisted on independent consideration of a test ban.

On 19 September 1957, the US conducted the first contained underground test at the Nevada Test Site

The Nevada National Security Site (N2S2 or NNSS), known as the Nevada Test Site (NTS) until 2010, is a United States Department of Energy (DOE) reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about 65 miles (105 km) northwest of the ...

, codenamed '' Rainier''. The ''Rainier'' shot complicated the push for a comprehensive test ban, as underground tests could not be as easily identified as atmospheric tests.

Despite Eisenhower's interest in a deal, his administration was hamstrung by discord among US scientists, technicians, and politicians. At one point, Eisenhower complained that "statecraft was becoming a prisoner of scientists." Until 1957, Strauss's AEC (including its Los Alamos and Livermore laboratories) was the dominant voice in the administration on nuclear affairs, with Teller's concerns over detection mechanisms also influencing Eisenhower. Unlike some others within the US scientific community, Strauss fervently advocated against a test ban, arguing that the US must maintain a clear nuclear advantage via regular testing and that the negative environmental impacts of such tests were overstated. Furthermore, Strauss repeatedly emphasized the risk of the Soviet Union violating a ban, a fear Eisenhower shared.

On 7 November 1957, after ''Sputnik'' and under pressure to bring on a dedicated science advisor, Eisenhower created the President's Science Advisory Committee

The President's Science Advisory Committee (PSAC) was created on November 21, 1957, by President of the United States Dwight D. Eisenhower, as a direct response to the Soviet launching of the Sputnik 1 and Sputnik 2 satellites. PSAC was an upgrad ...

(PSAC), which had the effect of eroding the AEC's monopoly over scientific advice. In stark contrast to the AEC, PSAC promoted a test ban and argued against Strauss's claims concerning its strategic implications and technical feasibility. In late 1957, the Soviet Union made a second offer of a three-year moratorium without inspections, but lacking any consensus within his administration, Eisenhower rejected it. In early 1958, the discord within American circles, particularly among scientists, was made clear in hearings before the Senate Subcommittee on Nuclear Disarmament, chaired by Senator Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing ...

. The hearings featured conflicting testimony from the likes of Teller and Linus Pauling, as well as from Harold Stassen, who argued that a test ban could safely be separated from broader disarmament, and AEC members, who argued that a cutoff in nuclear production should precede a test ban.

Khrushchev and a moratorium: 1958–1961

In the summer of 1957, Khrushchev was at acute risk of losing power, as theAnti-Party Group

The Anti-Party Group ( rus, Антипартийная группа, r=Antipartiynaya gruppa) was a Stalinist group within the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union that unsuccessfully attempted to depose Nikita Khrushchev as Fir ...

composed of former Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

allies Lazar Kaganovich

Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich, also Kahanovich (russian: Ла́зарь Моисе́евич Кагано́вич, Lázar' Moiséyevich Kaganóvich; – 25 July 1991), was a Soviet politician and administrator, and one of the main associates of ...

, Georgy Malenkov

Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov ( – 14 January 1988) was a Soviet politician who briefly succeeded Joseph Stalin as the leader of the Soviet Union. However, at the insistence of the rest of the Presidium, he relinquished control over the p ...

, and Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

launched an attempt to replace Khrushchev as General Secretary of the Communist Party (effectively the leader of the Soviet Union) with Nikolai Bulganin

Nikolai Alexandrovich Bulganin (russian: Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Булга́нин; – 24 February 1975) was a Soviet politician who served as Minister of Defense (1953–1955) and Premier of the Soviet Union (1955–19 ...

, then the Premier of the Soviet Union

The Premier of the Soviet Union (russian: Глава Правительства СССР) was the head of government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The office had four different names throughout its existence: Chairman of th ...

. The attempted ouster, which was foiled in June, was followed by a series of actions by Khrushchev to consolidate power. In October 1957, still feeling vulnerable from Anti-Party Group's ploy, Khrushchev forced out defense minister Georgy Zhukov

Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov ( rus, Георгий Константинович Жуков, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ ˈʐukəf, a=Ru-Георгий_Константинович_Жуков.ogg; 1 December 1896 – ...

, cited as "the nation's most powerful military man." On 27 March 1958, Khrushchev forced Bulganin to resign and succeeded him as Premier. Between 1957 and 1960, Khrushchev had his firmest grip on power, with little real opposition.

Khrushchev was personally troubled by the power of nuclear weapons and would later recount that he believed the weapons could never be used. In the mid-1950s, Khrushchev took a keen interest in defense policy and sought to inaugurate an era of détente

Détente (, French: "relaxation") is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The term, in diplomacy, originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsuccessfully to reduce ...

with the West. Initial efforts to reach accords, such as on disarmament at the 1955 Geneva Summit, proved fruitless, and Khrushchev saw test-ban negotiations as an opportunity to present the Soviet Union as "both powerful and responsible." At the 20th Communist Party Congress in 1956, Khrushchev declared that nuclear war should no longer be seen as "fatalistically inevitable." Simultaneously, however, Khrushchev expanded and advanced the Soviet nuclear arsenal at a cost to conventional Soviet forces (e.g., in early 1960, Khrushchev announced demobilization of 1.2 million troops).

On 31 March 1958, the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union

The Supreme Soviet of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics ( rus, Верховный Совет Союза Советских Социалистических Республик, r=Verkhovnyy Sovet Soyuza Sovetskikh Sotsialisticheskikh Respubl ...

approved a decision to halt nuclear testing, conditional on other nuclear powers doing the same. Khrushchev then called on Eisenhower and Macmillan to join the moratorium. Despite the action being met with widespread praise and an argument from Dulles that the US should reciprocate, Eisenhower dismissed the plan as a "gimmick"; the Soviet Union had just completed a testing series and the US was about to begin Operation Hardtack I

Operation Hardtack I was a series of 35 nuclear tests conducted by the United States from April 28 to August 18 in 1958 at the Pacific Proving Grounds. At the time of testing, the Operation Hardtack I test series included more nuclear detonatio ...

, a series of atmospheric, surface-level, and underwater nuclear tests. Eisenhower instead insisted that any moratorium be linked to reduced production of nuclear weapons. In April 1958, the US began Operation Hardtack I as planned. The Soviet declaration concerned the British government, which feared that the moratorium might lead to a test ban before its own testing program was completed. Following the Soviet declaration, Eisenhower called for an international meeting of experts to determine proper control and verification measures—an idea first proposed by British Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a Secretary of State (United Kingdom), minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwe ...

Selwyn Lloyd

John Selwyn Brooke Lloyd, Baron Selwyn-Lloyd, (28 July 1904 – 18 May 1978) was a British politician. Born and raised in Cheshire, he was an active Liberal as a young man in the 1920s. In the following decade, he practised as a barrister and ...

.

The advocacy of PSAC, including that of its chairmen James Rhyne Killian and George Kistiakowsky

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd President ...

, was a key factor in Eisenhower's eventual decision to initiate test-ban negotiations in 1958. In the spring of 1958, chairman Killian and the PSAC staff (namely Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Bethe (; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American theoretical physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics, and solid-state physics, and who won the 1967 Nobel ...

and Isidor Isaac Rabi

Isidor Isaac Rabi (; born Israel Isaac Rabi, July 29, 1898 – January 11, 1988) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1944 for his discovery of nuclear magnetic resonance, which is used in magnetic resonance ima ...

) undertook a review of US test-ban policy, determining that a successful system for detecting underground tests could be created. At the recommendation of Dulles (who had recently come to support a test ban), the review prompted Eisenhower to propose technical negotiations with the Soviet Union, effectively detaching test-ban negotiations from negotiations over a halt to nuclear weapons production (the one-time US demand). In explaining the policy shift, Eisenhower privately said that continued resistance to a test ban would leave the US in a state of "moral isolation."

On 8 April 1958, still resisting Khrushchev's call for a moratorium, Eisenhower invited the Soviet Union to join these technical negotiations in the form of a conference on the technical aspects of a test-ban, specifically the technical details of ensuring compliance with a ban. The proposal was, to a degree, a concession to the Soviet Union, as a test ban would be explored independent of the previously demanded cutoff in fissionable-material production. Khrushchev initially declined the invitation, but eventually agreed "in spite of the serious doubts" he had after Eisenhower suggested a technical agreement on verification would be a precursor to a test ban.

On 1 July 1958, responding to Eisenhower's call, the nuclear powers convened the Conference of Experts in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

, aimed at studying means of detecting nuclear tests. The conference included scientists from the US, Britain, the Soviet Union, Canada, Czechoslovakia, France, Poland, and Romania. The US delegation was led by James Fisk, a member of PSAC, the Soviets by Evgenii Fedorov, and the British delegation by William Penney

William George Penney, Baron Penney, (24 June 19093 March 1991) was an English mathematician and professor of mathematical physics at the Imperial College London and later the rector of Imperial College London. He had a leading role in the ...

, who had led the British delegation to the Manhattan Project. Whereas the US approached the conference solely from a technical perspective, Penney was specifically instructed by Macmillan to attempt to achieve a political agreement. This difference in approach was reflected in the broader composition of the US and UK teams. US experts were primarily drawn from academia and industry. Fisk was a vice president at Bell Telephone Laboratories and was joined by Robert Bacher

Robert Fox Bacher (August 31, 1905November 18, 2004) was an American nuclear physicist and one of the leaders of the Manhattan Project. Born in Loudonville, Ohio, Bacher obtained his undergraduate degree and doctorate from the University of Mic ...

and Ernest Lawrence, both physicists who had worked on the Manhattan Project. Conversely, British delegates largely held government positions. The Soviet delegation was composed primarily of academics, though virtually all of them had some link to the Soviet government. The Soviets shared the British goal of achieving an agreement at the conference.

At particular issue was the ability of sensors to differentiate an underground test from an earthquake. There were four techniques examined: measurement of acoustic wave

Acoustic waves are a type of energy propagation through a medium by means of adiabatic loading and unloading. Important quantities for describing acoustic waves are acoustic pressure, particle velocity, particle displacement and acoustic intensi ...

s, seismic signals, radio wave

Radio waves are a type of electromagnetic radiation with the longest wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, typically with frequencies of 300 gigahertz ( GHz) and below. At 300 GHz, the corresponding wavelength is 1 mm (sho ...

s, and inspection of radioactive debris. The Soviet delegation expressed confidence in each method, while Western experts argued that a more comprehensive compliance system would be necessary.

The Conference of Experts was characterized as "highly professional" and productive. By the end of August 1958, the experts devised an extensive control program, known as the "Geneva System," involving 160–170 land-based monitoring posts, plus 10 additional sea-based monitors and occasional flights over land following a suspicious event (with the inspection plane being provided and controlled by the state under inspection). The experts determined that such a scheme would be able to detect 90% of underground detonations, accurate to 5 kilotons, and atmospheric tests with a minimum yield of 1 kiloton. The US had initially advocated for 650 posts, versus a Soviet proposal of 100–110. The final recommendation was a compromise forged by the British delegation. In a widely publicized and well-received communiqué dated 21 August 1958, the conference declared that it "reached the conclusion that it is technically feasible to set up ... a workable and effective control system for the detection of violations of a possible agreement on the worldwide cessation of nuclear weapons tests."

The technical findings, released on 30 August 1958 in a report drafted by the Soviet delegation, were endorsed by the US and UK, which proposed that they serve as the basis for test-ban and international-control negotiations. However, the experts' report failed to address precisely who would do the monitoring and when on-site inspections—a US demand and Soviet concern—would be permitted. The experts also deemed detection of outer-space tests (tests more than above the earth's surface) to be impractical. Additionally, the size of the Geneva System may have rendered it too expensive to be put into effect. The 30 August report, which contained details on these limitations, received significantly less public attention than the 21 August communiqué.

Nevertheless, pleased by the findings, the Eisenhower administration proposed negotiations on a permanent test ban and announced it would self-impose a year-long testing moratorium if Britain and the Soviet Union did the same. This decision amounted to a victory for John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles (then the

The technical findings, released on 30 August 1958 in a report drafted by the Soviet delegation, were endorsed by the US and UK, which proposed that they serve as the basis for test-ban and international-control negotiations. However, the experts' report failed to address precisely who would do the monitoring and when on-site inspections—a US demand and Soviet concern—would be permitted. The experts also deemed detection of outer-space tests (tests more than above the earth's surface) to be impractical. Additionally, the size of the Geneva System may have rendered it too expensive to be put into effect. The 30 August report, which contained details on these limitations, received significantly less public attention than the 21 August communiqué.

Nevertheless, pleased by the findings, the Eisenhower administration proposed negotiations on a permanent test ban and announced it would self-impose a year-long testing moratorium if Britain and the Soviet Union did the same. This decision amounted to a victory for John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles (then the Director of Central Intelligence

The director of central intelligence (DCI) was the head of the American Central Intelligence Agency from 1946 to 2005, acting as the principal intelligence advisor to the president of the United States and the United States National Security C ...

), and PSAC, who had argued within the Eisenhower administration for separating a test ban from larger disarmament efforts, and a defeat for the Department of Defense Department of Defence or Department of Defense may refer to:

Current departments of defence

* Department of Defence (Australia)

* Department of National Defence (Canada)

* Department of Defence (Ireland)

* Department of National Defense (Philipp ...

and AEC, which had argued to the contrary.

In May 1958, Britain had informed the US that it would be willing to join a testing moratorium on 31 October 1958, by which point it would have finished its hydrogen-bomb testing, conditional on the US providing Britain with nuclear information following amendment of the McMahon Act. The US Congress approved amendments permitting greater collaboration in late June. Following Soviet assent on 30 August 1958 to the one-year moratorium, the three countries conducted a series of tests in September and October. At least 54 tests were conducted by the US and 14 by the Soviet Union in this period. On 31 October 1958 the three countries initiated test-ban negotiations (the Conference on the Discontinuance of Nuclear Tests) and agreed to a temporary moratorium (the Soviet Union joined the moratorium shortly after this date). The moratorium would last for close to three years.

The Conference on the Discontinuance of Nuclear Tests convened in Geneva at Moscow's request (the Western participants had proposed New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

). The US delegation was led by James Jeremiah Wadsworth

James Jeremiah "Jerry" Wadsworth (June 12, 1905 – March 13, 1984)"James J(eremiah) Wadsworth." Contemporary Authors Online. Detroit: Gale, 2002. Gale Biography In Context. Web. 27 Apr. 2011. was an American politician and diplomat from New Yor ...

, an envoy to the UN, the British by David Ormsby-Gore, the Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, and the Soviets by Semyon K. Tsarapkin, a disarmament expert with experience dating back to the 1946 Baruch Plan. The Geneva Conference began with a Soviet draft treaty grounded in the Geneva System. The three nuclear weapons states (the "original parties") would abide by a test ban, verified by the Geneva System, and work to prevent testing by potential nuclear states (such as France). This was rejected by Anglo-American negotiators due to fears that the verification provisions were too vague and the Geneva System too weak.

Shortly after the Geneva Conference began in the fall of 1958, Eisenhower faced renewed domestic opposition to a comprehensive test ban as Senator Albert Gore Sr.

Albert Arnold Gore (December 26, 1907 – December 5, 1998) was an American politician who served as a United States Senator from Tennessee from 1953 to 1971. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as a U.S. Representative f ...

argued in a widely circulated letter that a partial ban would be preferable due to Soviet opposition to strong verification measures.

The Gore letter did spur some progress in negotiations, as the Soviet Union allowed in late November 1958 for explicit control measures to be included in the text of the drafted treaty. By March 1959, the negotiators had agreed upon seven treaty articles, but they primarily concerned uncontroversial issues and a number of disputes over verification persisted. First, the Soviet verification proposal was deemed by the West to be too reliant on self-inspection, with control posts primarily staffed by citizens of the country housing the posts and a minimal role for officials from the international supervisory body. The West insisted that half of a control post staff be drawn from another nuclear state and half from neutral parties. Second, the Soviet Union required that the international supervisory body, the Control Commission, require unanimity before acting; the West rejected the idea of giving Moscow a veto over the commission's proceedings. Finally, the Soviet Union preferred temporary inspection teams drawn from citizens of the country under inspection, while the West insisted on permanent teams composed of inspectors from the Control Commission.

Additionally, despite the initial positive response to the Geneva experts' report, data gathered from Hardtack operations of 1958 (namely the underground ''Rainier'' shot) would further complication verification provisions as US scientists, including Hans Bethe (who backed a ban), became convinced that the Geneva findings were too optimistic regarding detection of underground tests, though Macmillan warned that using the data to block progress on a test ban might be perceived in the public as a political ploy. In early 1959, Wadsworth told Tsarapkin of new US skepticism towards the Geneva System. While the Geneva experts believed the system could detect underground tests down to five kilotons, the US now believed that it could only detect tests down to 20 kilotons (in comparison, the Little Boy

"Little Boy" was the type of atomic bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on 6 August 1945 during World War II, making it the first nuclear weapon used in warfare. The bomb was dropped by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ''Enola Gay'' p ...

bomb dropped on Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui ...

had an official yield of 13 kilotons). As a result, the Geneva detection regime and the number of control posts would have to be significantly expanded, including new posts within the Soviet Union. The Soviets dismissed the US argument as a ruse, suggesting that the Hardtack data had been falsified.

In early 1959, a roadblock to an agreement was removed as Macmillan and Eisenhower, over opposition from the Department of Defense, agreed to consider a test ban separately from broader disarmament endeavors.

On 13 April 1959, facing Soviet opposition to on-site detection systems for underground tests, Eisenhower proposed moving from a single, comprehensive test ban to a graduated agreement where atmospheric tests—those up to 50 km (31 mi) high, a limit Eisenhower would revise upward in May 1959—would be banned first, with negotiations on underground and outer-space tests continuing. This proposal was turned down on 23 April 1959 by Khrushchev, calling it a "dishonest deal." On 26 August 1959, the US announced it would extend its year-long testing moratorium to the end of 1959, and would not conduct tests after that point without prior warning. The Soviet Union reaffirmed that it would not conduct tests if the US and UK continued to observe a moratorium.

To break the deadlock over verification, Macmillan proposed a compromise in February 1959 whereby each of the original parties would be subject to a set number of on-site inspections each year. In May 1959, Khrushchev and Eisenhower agreed to explore Macmillan's quota proposal, though Eisenhower made further test-ban negotiations conditional on the Soviet Union dropping its Control Commission veto demand and participating in technical discussions on identification of high-altitude nuclear explosions. Khrushchev agreed to the latter and was noncommittal on the former. A working group in Geneva would eventually devise a costly system of 5–6 satellites orbiting at least above the earth, though it could not say with certainty that such a system would be able to determine the origin of a high-altitude test. US negotiators also questioned whether high-altitude tests could evade detection via radiation shielding

Radiation protection, also known as radiological protection, is defined by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) as "The protection of people from harmful effects of exposure to ionizing radiation, and the means for achieving this". Exposur ...

. Concerning Macmillan's compromise, the Soviet Union privately suggested it would accept a quota of three inspections per year. The US argued that the quota should be set according to scientific necessity (i.e., be set according to the frequency of seismic events).

In June 1959, a report of a panel headed by Lloyd Berkner, a physicist, was introduced into discussions by Wadsworth. The report specifically concerned whether the Geneva System could be improved without increasing the number of control posts. Berkner's proposed measures were seen as highly costly and the technical findings themselves were accompanied by a caveat about the panel's high degree of uncertainty given limited data. Around the same time, analysis conducted by the Livermore National Laboratory and RAND Corporation

The RAND Corporation (from the phrase "research and development") is an American nonprofit global policy think tank created in 1948 by Douglas Aircraft Company to offer research and analysis to the United States Armed Forces. It is finance ...

at Teller's instruction found that the seismic effect of an underground test could be artificially dampened (referred to as "decoupling") to the point that a 300-kiloton detonation would appear in seismic readings as a one-kiloton detonation. These findings were largely affirmed by pro-ban scientists, including Bethe. The third blow to the verification negotiations was provided by a panel chaired by Robert Bacher, which found that even on-site inspections would have serious difficulty determining whether an underground test had been conducted.

In September 1959, Khrushchev visited the US While the test ban was not a focus on conversations, a positive meeting with Eisenhower at Camp David

Camp David is the country retreat for the president of the United States of America. It is located in the wooded hills of Catoctin Mountain Park, in Frederick County, Maryland, near the towns of Thurmont and Emmitsburg, about north-northwest ...

eventually led Tsarapkin to propose a technical working group in November 1959 that would consider the issues of on-site inspections and seismic decoupling in the "spirit of Camp David." Within the working group, Soviet delegates allowed for the timing of on-site inspections to be grounded in seismic data, but insisted on conditions that were seen as excessively strict. The Soviets also recognized the theory behind decoupling, but dismissed its practical applications. The working group closed in December with no progress and significant hostility. Eisenhower issued a statement blaming "the recent unwillingness of the politically guided Soviet experts to give serious scientific consideration to the effectiveness of seismic techniques for the detection of underground nuclear explosions." Eisenhower simultaneously declared that the US would not be held to its testing moratorium when it expired on 31 December 1959, though pledged to not test if Geneva talks progressed. The Soviet Union followed by reiterating its decision to not test as long as Western states did not test.

In early 1960, Eisenhower indicated his support for a comprehensive test ban conditional on proper monitoring of underground tests. On 11 February 1960, Wadsworth announced a new US proposal by which only tests deemed verifiable by the Geneva System would be banned, including all atmospheric, underwater, and outer-space tests within detection range. Underground tests measuring more than 4.75 on the Richter scale

The Richter scale —also called the Richter magnitude scale, Richter's magnitude scale, and the Gutenberg–Richter scale—is a measure of the strength of earthquakes, developed by Charles Francis Richter and presented in his landmark 1935 ...

would also be barred, subject to revision as research on detection continued. Adopting Macmillan's quota compromise, the US proposed each nuclear state be subject to roughly 20 on-site inspections per year (the precise figure based on the frequency of seismic events).

Tsarapkin responded positively to the US proposal, though was wary of the prospect of allowing underground tests registering below magnitude 4.75. In its own proposal offered 19 March 1960 the Soviet Union accepted most US provisions, with certain amendments. First, the Soviet Union asked that underground tests under magnitude 4.75 be banned for a period of four-to-five years, subject to extension. Second, it sought to prohibit all outer-space tests, whether within detection range or not. Finally, the Soviet Union insisted that the inspection quota be determined on a political basis, not a scientific one. The Soviet offer faced a mixed reception. In the US, Senator Hubert Humphrey and the Federation of American Scientists

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is an American nonprofit global policy think tank with the stated intent of using science and scientific analysis to attempt to make the world more secure. FAS was founded in 1946 by scientists who w ...

(which was typically seen as supportive of a test ban) saw it as a clear step towards an agreement. Conversely, AEC chairman John A. McCone and Senator Clinton Presba Anderson

Clinton Presba Anderson (October 23, 1895 – November 11, 1975) was an American politician who represented New Mexico in the United States Senate from 1949 until 1973. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as United State ...

, chair of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, argued that the Soviet system would be unable to prevent secret tests. That year, the AEC published a report arguing that the continuing testing moratorium risked "free world supremacy in nuclear weapons," and that renewed testing was critical for further weapons development. The joint committee also held hearings in April which cast doubt on the technical feasibility and cost of the proposed verification measures. Additionally, Teller continued to warn of the dangerous consequences of a test ban and the Department of Defense (including Neil H. McElroy and Donald A. Quarles, until recently its top two officials) pushed to continue testing and expand missile stockpiles.

Shortly after the Soviet proposal, Macmillan met with Eisenhower at Camp David to devise a response. The Anglo-American counterproposal agreed to ban small underground tests (those under magnitude 4.75) on a temporary basis (a duration of roughly 1 year, versus the Soviet proposal of 4–5 years), but this could only happen after verifiable tests had been banned and a seismic research group (the Seismic Research Program Advisory Group) convened. The Soviet Union responded positively to the counterproposal and the research group convened on 11 May 1960. The Soviet Union also offered to keep an underground ban out of the treaty under negotiation. In May 1960, there were high hopes that an agreement would be reached at an upcoming summit of Eisenhower, Khrushchev, Macmillan, and Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Governm ...

of France in Paris.

A test ban seemed particularly close in 1960, with Britain and France in accord with the US (though France conducted its first nuclear test in February) and the Soviet Union having largely accepted the Macmillan-Eisenhower proposal. But US-Soviet relations soured after an American U-2 spy plane was shot down in Soviet airspace in May 1960. The Paris summit was abruptly cancelled and the Soviet Union withdrew from the seismic research group, which subsequently dissolved. Meetings of the Geneva Conference continued until December, but little progress was made as Western-Soviet relations continued to grow more antagonistic through the summer, punctuated by the Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis (french: Crise congolaise, link=no) was a period of political upheaval and conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The crisis began almost immediately after ...