Parliament of 1327 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Parliament of 1327, which sat at the

The Parliament of 1327, which sat at the

France had recently invaded the

France had recently invaded the

From February 1326 it was clear in England that Isabella and Mortimer intended to invade. Despite false alarms, large ships, as a defensive measure, were forbidden from leaving English ports, and some were pressed into royal service. King Edward declared war on France in July; Isabella and Mortimer invaded England in September, landing in

From February 1326 it was clear in England that Isabella and Mortimer intended to invade. Despite false alarms, large ships, as a defensive measure, were forbidden from leaving English ports, and some were pressed into royal service. King Edward declared war on France in July; Isabella and Mortimer invaded England in September, landing in

Isabella, Mortimer and the lords arrived in London on 4 January 1327. In response to the previous year's spate of murders, Londoners had been forbidden to bear arms, and two days later all citizens had sworn an oath to keep the peace. Parliament met on 7 January to consider the state of the realm now the King was incarcerated. It had originally been summoned by Isabella and the Prince, in the name of the King, on 28 October the previous year. Parliament had been intended to assemble on 14 December 1326, but on 3 December—still in the name of the King—further writs were issued deferring the sitting until early the next year. This, it was implied, was due to the King being abroad, rather than imprisoned. Because of this, parliament would have to be held before the Queen and Prince Edward. '' The History of Parliament Trust'' has described the legality of the writs as being "highly questionable", and C. T. Wood called the sitting "a show of pseudo-parliamentary regularity", "stage-managed" by Mortimer and Thomas, Lord Wake. For Isabella and Mortimer, governing through parliament was only a temporary solution to a constitutional problem, because at some point their positions would likely be challenged legally. Thus, suggests Ormrod, they had to enforce a solution favourable to Mortimer and the Queen, by any means they could.

Contemporaries were uncertain as to the legality of Isabella's parliament. Edward II was still king, although in official documents, this was only alongside his "most beloved consort Isabella queen of England" and his "firstborn son keeper of the kingdom", in what Phil Bradford called as a "nominal presidency". King Edward was said to be abroad when in reality he was imprisoned in Kenilworth Castle. It was maintained that he desired a "''colloquium''" and a "''tractatum''" (conference and consultation) with his lords "upon various affairs touching himself and the state of his kingdom", hence the holding of parliament. Supposedly it was Edward II himself who postponed the first sitting until January, "for certain necessary causes and utilities", presumably at the behest of the Queen and Mortimer.

A priority for the new regime was deciding what to do with Edward II. Mortimer considered holding a state trial for treason, in the expectation of a guilty verdict and a death sentence. He and other lords discussed the matter at Isabella's

Isabella, Mortimer and the lords arrived in London on 4 January 1327. In response to the previous year's spate of murders, Londoners had been forbidden to bear arms, and two days later all citizens had sworn an oath to keep the peace. Parliament met on 7 January to consider the state of the realm now the King was incarcerated. It had originally been summoned by Isabella and the Prince, in the name of the King, on 28 October the previous year. Parliament had been intended to assemble on 14 December 1326, but on 3 December—still in the name of the King—further writs were issued deferring the sitting until early the next year. This, it was implied, was due to the King being abroad, rather than imprisoned. Because of this, parliament would have to be held before the Queen and Prince Edward. '' The History of Parliament Trust'' has described the legality of the writs as being "highly questionable", and C. T. Wood called the sitting "a show of pseudo-parliamentary regularity", "stage-managed" by Mortimer and Thomas, Lord Wake. For Isabella and Mortimer, governing through parliament was only a temporary solution to a constitutional problem, because at some point their positions would likely be challenged legally. Thus, suggests Ormrod, they had to enforce a solution favourable to Mortimer and the Queen, by any means they could.

Contemporaries were uncertain as to the legality of Isabella's parliament. Edward II was still king, although in official documents, this was only alongside his "most beloved consort Isabella queen of England" and his "firstborn son keeper of the kingdom", in what Phil Bradford called as a "nominal presidency". King Edward was said to be abroad when in reality he was imprisoned in Kenilworth Castle. It was maintained that he desired a "''colloquium''" and a "''tractatum''" (conference and consultation) with his lords "upon various affairs touching himself and the state of his kingdom", hence the holding of parliament. Supposedly it was Edward II himself who postponed the first sitting until January, "for certain necessary causes and utilities", presumably at the behest of the Queen and Mortimer.

A priority for the new regime was deciding what to do with Edward II. Mortimer considered holding a state trial for treason, in the expectation of a guilty verdict and a death sentence. He and other lords discussed the matter at Isabella's

Before parliament met, the lords had sent

Before parliament met, the lords had sent

During the sermons, the articles of deposition were officially presented to the assembly. In contrast to the elaborate and floridly hyperbolic accusations previously launched at the Despensers, this was a relatively simple document. The King was accused of being incapable of fair rule; of indulging false counsellors; preferring his own amusements to good government; neglecting England and losing Scotland; dilapidating the church and imprisoning the clergy; and, all in all, being in fundamental breach of the coronation oath he had made to his subjects. All of which, the rebels claimed, was so well known as to be undeniable. The articles accused Edward's favourites of tyranny although not the King himself, whom they described as "incorrigible, without hope of reform". England's succession of military failures in Scotland and France rankled with the lords: Edward had fought no successful campaigns in either theatre, yet had raised enormous levies to enable him to do so. Such levies says

During the sermons, the articles of deposition were officially presented to the assembly. In contrast to the elaborate and floridly hyperbolic accusations previously launched at the Despensers, this was a relatively simple document. The King was accused of being incapable of fair rule; of indulging false counsellors; preferring his own amusements to good government; neglecting England and losing Scotland; dilapidating the church and imprisoning the clergy; and, all in all, being in fundamental breach of the coronation oath he had made to his subjects. All of which, the rebels claimed, was so well known as to be undeniable. The articles accused Edward's favourites of tyranny although not the King himself, whom they described as "incorrigible, without hope of reform". England's succession of military failures in Scotland and France rankled with the lords: Edward had fought no successful campaigns in either theatre, yet had raised enormous levies to enable him to do so. Such levies says

Indeed, it has been suggested Richard II may have been responsible for the disappearance of the 1327 parliament roll when he recovered personal power two years later. Given-Wilson says that Richard considered Edward's deposition a "stain which he was determined to remove" from the royal family's history by proposing Edward's canonisation. Richard's subsequent deposition by

Indeed, it has been suggested Richard II may have been responsible for the disappearance of the 1327 parliament roll when he recovered personal power two years later. Given-Wilson says that Richard considered Edward's deposition a "stain which he was determined to remove" from the royal family's history by proposing Edward's canonisation. Richard's subsequent deposition by

The Parliament of 1327, which sat at the

The Parliament of 1327, which sat at the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north b ...

between 7 January and 9 March 1327, was instrumental in the transfer of the English Crown

This list of kings and reigning queens of the Kingdom of England begins with Alfred the Great, who initially ruled Wessex, one of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which later made up modern England. Alfred styled himself King of the Anglo-Sa ...

from King Edward II to his son, Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

. Edward II had become increasingly unpopular with the English nobility

The British nobility is made up of the peerage and the (landed) gentry. The nobility of its four constituent home nations has played a major role in shaping the history of the country, although now they retain only the rights to stand for election ...

due to the excessive influence of unpopular court favourites, the patronage he accorded them, and his perceived ill-treatment of the nobility. By 1325, even his wife, Queen Isabella, despised him. Towards the end of the year, she took the young Edward to her native France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, where she entered into an alliance with the powerful and wealthy nobleman Roger Mortimer, who her husband previously had exiled. The following year, they invaded England to depose Edward II. Almost immediately, the King's resistance was beset by betrayal, and he eventually abandoned London and fled west, probably to raise an army in Wales or Ireland. He was soon captured and imprisoned.

Isabella and Mortimer summoned a parliament to confer legitimacy on their regime. The meeting began gathering at Westminster on 7 January, but little could be done in the absence of the King. The fourteen-year-old Edward was proclaimed "Keeper of the Realm" (but not yet king), and a parliamentary deputation was sent to Edward II asking him to allow himself to be brought to parliament. He refused, and the parliament continued without him. The King was accused of offences ranging from the promotion of favourites to the destruction of the church, resulting in a betrayal of his coronation oath to the people. These were known as the "Articles of Accusation". The City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

was particularly aggressive in its attacks on Edward II, and its citizens may have helped intimidate those attending the parliament into agreeing to the King's deposition

Deposition may refer to:

* Deposition (law), taking testimony outside of court

* Deposition (politics), the removal of a person of authority from political power

* Deposition (university), a widespread initiation ritual for new students practiced f ...

, which occurred on the afternoon of 13 January.

On or around 21 January, the Lords Temporal

The Lords Temporal are secular members of the House of Lords, the upper house of the British Parliament. These can be either life peers or hereditary peers, although the hereditary right to sit in the House of Lords was abolished for all but ...

sent another delegation to the King to inform him of his deposition, effectively giving Edward an ultimatum: if he did not agree to hand over the crown to his son, then the lords in parliament would give it to somebody outside the royal family. King Edward wept but agreed to their conditions. The delegation returned to London, and Edward III was proclaimed king immediately. He was crowned on 1 February 1327. In the aftermath of the parliamentary session, his father remained imprisoned, being moved around to prevent attempted rescues; he died—presumed killed, probably on Mortimer's orders—that September. Crises continued for Mortimer and Isabella, who were ''de facto'' rulers of the country, partly because of Mortimer's own greed, mismanagement, and mishandling of the new king. Edward III led a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

against Mortimer in 1330, overthrew him, and began his personal rule.

Background

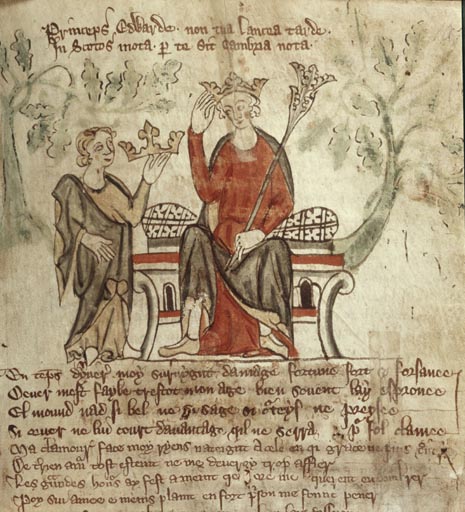

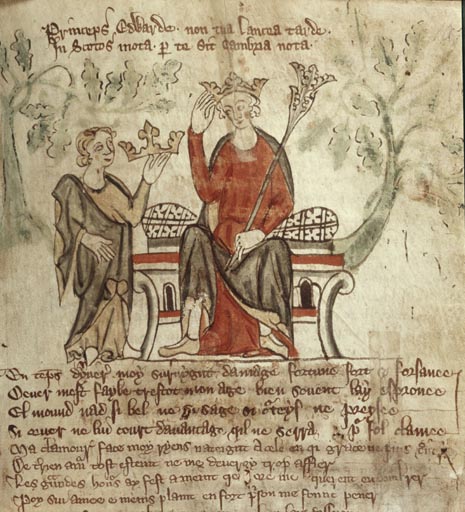

KingEdward II of England

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

had court favourites who were unpopular with his nobility, such as Piers Gaveston

Piers Gaveston, Earl of Cornwall (c. 1284 – 19 June 1312) was an English nobleman of Gascon origin, and the favourite of Edward II of England.

At a young age, Gaveston made a good impression on King Edward I, who assigned him to the househ ...

and Hugh Despenser the Younger

Hugh le Despenser, 1st Baron le Despenser (c. 1287/1289 – 24 November 1326), also referred to as "the Younger Despenser", was the son and heir of Hugh le Despenser, Earl of Winchester (the Elder Despenser), by his wife Isabella de Beaucham ...

. Gaveston was killed during an earlier noble rebellion against Edward in 1312, and Despenser was hated by the English nobility. Edward was also unpopular with the common people due to his repeated demands from them for unpaid military service in Scotland. None of his campaigns there were successful, and this led to a further decline in his popularity, particularly with the nobility. His image was further diminished in 1322 when he executed his cousin, Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, and confiscated the Lancaster estates. Historian Chris Given-Wilson

Chris Given-Wilson (born 1949) is a British historian and academic, specialising in medieval history. He was Professor of History of the University of St Andrews, where he is now professor emeritus. He is the author of a number of books.

Car ...

has written how by 1325 the nobility believed that "no landholder could feel safe" under the regime. This distrust of Edward was shared by his wife, Isabella of France

Isabella of France ( – 22 August 1358), sometimes described as the She-Wolf of France (), was Queen of England as the wife of King Edward II, and regent of England from 1327 until 1330. She was the youngest surviving child and only surviving ...

, who believed Despenser responsible for poisoning the King's mind against her. In September 1324 Queen Isabella had been publicly humiliated when the government declared her an enemy alien, and the King had immediately repossessed her estates, probably at the urging of Despenser. Edward also disbanded her retinue. Edward had already been threatened with deposition on two previous occasions (in 1310 and 1321). Historians agree that hostility towards Edward was universal. W. H. Dunham and C. T. Wood ascribed this to Edward's "cruelty and personal faults", suggesting that "very few, not even his half-brothers or his son, seemed to care about the wretched man" and that none would fight for him. A contemporary chronicler described Edward as ''rex inutilis'', or a "useless king".

France had recently invaded the

France had recently invaded the Duchy of Aquitaine

The Duchy of Aquitaine ( oc, Ducat d'Aquitània, ; french: Duché d'Aquitaine, ) was a historical fiefdom in western, central, and southern areas of present-day France to the south of the river Loire, although its extent, as well as its name, flu ...

, then an English royal possession. In response, King Edward sent Isabella to Paris, accompanied by their thirteen-year-old son, Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sax ...

, to negotiate a settlement. Contemporaries believed she had sworn, on leaving, never to return to England with the Despensers in power. Soon after her arrival, correspondence between Isabella and her husband, as well between them and her brother King Charles IV of France

Charles IV (18/19 June 1294 – 1 February 1328), called the Fair (''le Bel'') in France and the Bald (''el Calvo'') in Navarre, was last king of the direct line of the House of Capet, King of France and King of Navarre (as Charles I) from 132 ...

and Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII ( la, Ioannes PP. XXII; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death in December 1334.

He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Pope, elected b ...

, effectively disclosed the royal couple's increasing estrangement to the world. A contemporary chronicler reports how Isabella and Edward became increasingly scathing of each other, worsening relations. By December 1325 she had entered into a possibly sexual relationship in Paris with the wealthy exiled nobleman Roger Mortimer. This was public knowledge in England by March 1326, and the King openly considered a divorce. He demanded that Isabella and Edward return to England, which they refused to do: "she sent back many of her retinue but gave trivial excuses for not returning herself" noted her biographer, John Parsons. Their son's failure to break with his mother angered the King further. Isabella became more strident in her criticisms of Edward's government, particularly against Walter de Stapledon, Bishop of Exeter, a close associate of the King and Despenser. King Edward alienated his son by putting the prince's estates under royal administration in January 1326, and the following month the King ordered that both he and his mother be arrested on landing in England.

While in Paris, the Queen became the head of King Edward's exiled opposition. Along with Mortimer, this group included Edmund of Woodstock, Earl of Kent

Edmund of Woodstock, 1st Earl of Kent (5 August 130119 March 1330), whose seat was Arundel Castle in Sussex, was the sixth son of King Edward I of England, and the second by his second wife Margaret of France, and was a younger half-brother o ...

, Henry de Beaumont

Henry de Beaumont (before 1280 – 10 March 1340), ''jure uxoris'' 4th Earl of Buchan and ''suo jure'' 1st Baron Beaumont, was a key figure in the Anglo-Scots wars of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, known as the Wars of Scottish Inde ...

, John de Botetourt, John Maltravers and William Trussell

Sir William Trussell was an English politician and leading rebel in Queen Isabella and Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March's rebellion against Edward II. William acted as Speaker of the House of Commons and renounced the allegiance of England t ...

. All were united by hatred of the Despensers. Isabella portrayed her and Prince Edward as seeking refuge from her husband and his court, both of whom she claimed were hostile to her, and claimed protection from Edward II. King Charles refused to countenance an invasion of England; instead, the rebels gained the Count of Hainaut's backing. In return, Isabella agreed that her son would marry the Count's daughter Philippa

Philippa is a feminine given name meaning "lover of horses" or " horses' friend". Common alternative spellings include ''Filippa'' and ''Phillipa''. Less common is ''Filipa'' and even ''Philippe'' (cf. the French spelling of '' Philippa of Guelder ...

. This was a further insult to Edward II, who had intended to use his eldest son's marriage as a bargaining tool against France, probably intending a marriage alliance with Spain.

Invasion of England

Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include ...

on the 24th. The commander of the royal fleet assisted the rebels: the first of many betrayals Edward II suffered. Isabella and Mortimer soon found they had significant support among the English political class. They were quickly joined by Thomas, Earl of Norfolk, the King's brother, accompanied by Henry, Earl of Leicester (brother of the executed Earl of Lancaster), and soon afterwards arrived the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

and the Bishops of Hereford

The Bishop of Hereford is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Hereford in the Province of Canterbury.

The episcopal see is centred in the City of Hereford where the bishop's seat ('' cathedra'') is in the Cathedral Church of S ...

and Lincoln. Within the week, support for the King had dissolved, and, accompanied by Despenser, he deserted London and travelled west. Edward's flight to the west precipitated his downfall. Historian Michael Prestwich

Michael Charles Prestwich OBE (born 30 January 1943) is an English historian, specialising on the history of medieval England, in particular the reign of Edward I. He is retired, having been Professor of History at Durham University and He ...

describes the King's support as collapsing "like a building hit by an earthquake". Edward's rule was already weak, and "even before the invasion, along with preparation, there had been panic. Now there was simply panic". Ormrod notes how

King Edward's attempt to raise an army in South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

was to no avail, and he and Despenser were captured on 16 November 1326 near Llantrisant

Llantrisant (; " Parish of the Three Saints") is a town in the county borough of Rhondda Cynon Taf, within the historic county boundaries of Glamorgan, Wales, lying on the River Ely and the Afon Clun. The three saints of the town's name are ...

. This, along with the unexpected swiftness with which the entire regime had collapsed, forced Isabella and Mortimer to wield executive power until they made arrangements for a successor to the throne. The King was incarcerated by the Earl of Leicester, while those suspected of being Despenser spies or supporters of the King—particularly in London, which was aggressively loyal to the Queen—were murdered by mobs.

Isabella spent the last months of 1326 in the West Country

The West Country (occasionally Westcountry) is a loosely defined area of South West England, usually taken to include all, some, or parts of the counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Bristol, and, less commonly, Wiltshire, Glouc ...

, and while in Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city, Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Glouces ...

witnessed the hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

of Despenser's father, the Earl of Winchester on 27 October. Despenser himself was captured in Hereford

Hereford () is a cathedral city, civil parish and the county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, south-west of Worcester, England, Worcester and north-west of Gloucester. ...

and executed there within the month. In Bristol Isabella, Mortimer and the accompanying lords discussed strategy. Not yet possessing the Great Seal, on 26 October they proclaimed the young Edward guardian of the realm, declaring that "by the assent of the whole community of the said kingdom present there, they unanimously chose dward IIIas keeper of the said kingdom". He was not yet officially declared king. The rebels' description of themselves as a community deliberately harked back to the reform movement of Simon de Montfort and the baronial league, which had described its reform programme as being of the community of the realm against Henry III. Claire Valente has pointed out how, in reality, the most common phrase heard "was not 'the community of the realm', but 'the quarrel of the earl of Lancaster'", illustrating how the struggle was still a factional one within baronial politics, whatever cloak it may have appeared to possess as a reform movement.

By 20 November 1326 the Bishop of Hereford had retrieved the Great Seal from the King, and delivered it to the King's son. He could now be announced as his father's heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

. Although, at this stage, it might still have been possible for Edward II to remain king, says Ormrod, "the writing was on the wall". A document issued by Isabella and her son at this time described their respective positions thus:

Summoning of parliament

Isabella, Mortimer and the lords arrived in London on 4 January 1327. In response to the previous year's spate of murders, Londoners had been forbidden to bear arms, and two days later all citizens had sworn an oath to keep the peace. Parliament met on 7 January to consider the state of the realm now the King was incarcerated. It had originally been summoned by Isabella and the Prince, in the name of the King, on 28 October the previous year. Parliament had been intended to assemble on 14 December 1326, but on 3 December—still in the name of the King—further writs were issued deferring the sitting until early the next year. This, it was implied, was due to the King being abroad, rather than imprisoned. Because of this, parliament would have to be held before the Queen and Prince Edward. '' The History of Parliament Trust'' has described the legality of the writs as being "highly questionable", and C. T. Wood called the sitting "a show of pseudo-parliamentary regularity", "stage-managed" by Mortimer and Thomas, Lord Wake. For Isabella and Mortimer, governing through parliament was only a temporary solution to a constitutional problem, because at some point their positions would likely be challenged legally. Thus, suggests Ormrod, they had to enforce a solution favourable to Mortimer and the Queen, by any means they could.

Contemporaries were uncertain as to the legality of Isabella's parliament. Edward II was still king, although in official documents, this was only alongside his "most beloved consort Isabella queen of England" and his "firstborn son keeper of the kingdom", in what Phil Bradford called as a "nominal presidency". King Edward was said to be abroad when in reality he was imprisoned in Kenilworth Castle. It was maintained that he desired a "''colloquium''" and a "''tractatum''" (conference and consultation) with his lords "upon various affairs touching himself and the state of his kingdom", hence the holding of parliament. Supposedly it was Edward II himself who postponed the first sitting until January, "for certain necessary causes and utilities", presumably at the behest of the Queen and Mortimer.

A priority for the new regime was deciding what to do with Edward II. Mortimer considered holding a state trial for treason, in the expectation of a guilty verdict and a death sentence. He and other lords discussed the matter at Isabella's

Isabella, Mortimer and the lords arrived in London on 4 January 1327. In response to the previous year's spate of murders, Londoners had been forbidden to bear arms, and two days later all citizens had sworn an oath to keep the peace. Parliament met on 7 January to consider the state of the realm now the King was incarcerated. It had originally been summoned by Isabella and the Prince, in the name of the King, on 28 October the previous year. Parliament had been intended to assemble on 14 December 1326, but on 3 December—still in the name of the King—further writs were issued deferring the sitting until early the next year. This, it was implied, was due to the King being abroad, rather than imprisoned. Because of this, parliament would have to be held before the Queen and Prince Edward. '' The History of Parliament Trust'' has described the legality of the writs as being "highly questionable", and C. T. Wood called the sitting "a show of pseudo-parliamentary regularity", "stage-managed" by Mortimer and Thomas, Lord Wake. For Isabella and Mortimer, governing through parliament was only a temporary solution to a constitutional problem, because at some point their positions would likely be challenged legally. Thus, suggests Ormrod, they had to enforce a solution favourable to Mortimer and the Queen, by any means they could.

Contemporaries were uncertain as to the legality of Isabella's parliament. Edward II was still king, although in official documents, this was only alongside his "most beloved consort Isabella queen of England" and his "firstborn son keeper of the kingdom", in what Phil Bradford called as a "nominal presidency". King Edward was said to be abroad when in reality he was imprisoned in Kenilworth Castle. It was maintained that he desired a "''colloquium''" and a "''tractatum''" (conference and consultation) with his lords "upon various affairs touching himself and the state of his kingdom", hence the holding of parliament. Supposedly it was Edward II himself who postponed the first sitting until January, "for certain necessary causes and utilities", presumably at the behest of the Queen and Mortimer.

A priority for the new regime was deciding what to do with Edward II. Mortimer considered holding a state trial for treason, in the expectation of a guilty verdict and a death sentence. He and other lords discussed the matter at Isabella's Wallingford Castle

Wallingford Castle was a major medieval castle situated in Wallingford in the English county of Oxfordshire (historically Berkshire), adjacent to the River Thames. Established in the 11th century as a motte-and-bailey design within an Anglo-Sa ...

just after Christmas, but with no agreement. The Lords Temporal

The Lords Temporal are secular members of the House of Lords, the upper house of the British Parliament. These can be either life peers or hereditary peers, although the hereditary right to sit in the House of Lords was abolished for all but ...

affirmed that Edward had failed his country so gravely that only his death could heal it; the attending bishops, on the other hand, held that whatever his faults, he had been anointed king by God. This presented Isabella and Mortimer with two problems. First, the bishops' argument would be popularly understood as risking the wrath of God. Second, public trials always bring the danger of an unintended verdict, particularly as it seems likely a broad body of public opinion doubted whether an anointed king could even commit treason. Such a result would mean not only Edward's release but his restoration to the throne. Mortimer and Isabella sought to avoid a trial and yet keep Edward II imprisoned for life. The King's imprisonment (officially by his son) had become public knowledge, and Isabella's and Mortimer's hand was forced as the arguments for the young Edward being named keeper of the kingdom were now groundless (as the King had clearly returned to his realm—one way or another).

Attendance

No parliament had sat since November 1325. Only 26 of the 46 barons who had been summoned in October 1326 for the December parliament were then also summoned to that of January 1327, and six of those had never received summonses under Edward II at all. Officially, the instigators of the parliament were the Bishops of Hereford and Winchester, Roger Mortimer and Thomas Wake; Isabella almost certainly played a background role. They summoned, asLords Spiritual

The Lords Spiritual are the bishops of the Church of England who serve in the House of Lords of the United Kingdom. 26 out of the 42 diocesan bishops and archbishops of the Church of England serve as Lords Spiritual (not counting retired archbi ...

, the Archbishop of Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of t ...

and fifteen English and four Welsh bishops as well as nineteen abbots. The Lords Temporal were represented by the Earls of Norfolk, Kent, Lancaster, Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant ur ...

, Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Atholl

Atholl or Athole ( gd, Athall; Old Gaelic ''Athfhotla'') is a large historical division in the Scottish Highlands, bordering (in anti-clockwise order, from Northeast) Marr, Badenoch, Lochaber, Breadalbane, Strathearn, Perth, and Gowrie. H ...

and Hereford

Hereford () is a cathedral city, civil parish and the county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately east of the border with Wales, south-west of Worcester, England, Worcester and north-west of Gloucester. ...

. Forty-seven baron

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or kn ...

s, twenty-three royal justice

Royal justices were an innovation in the law reforms of the Angevin kings of England. Royal justices were roving officials of the king, sent to seek out notorious robbers and murderers and bring them to justice.

The first important step dates fro ...

s, and several knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

s and burgesses were summoned from the shire

Shire is a traditional term for an administrative division of land in Great Britain and some other English-speaking countries such as Australia and New Zealand. It is generally synonymous with county. It was first used in Wessex from the begin ...

s and the Cinque Ports

The Confederation of Cinque Ports () is a historic group of coastal towns in south-east England – predominantly in Kent and Sussex, with one outlier ( Brightlingsea) in Essex. The name is Old French, meaning "five harbours", and alludes to t ...

. They may well have been encouraged, suggests Maddicott, by the wages to be paid to those attending: the "handsome sum" of four shillings a day for a knight and two for a burgess. The knights provided the bulk of Isabella's and the Prince's vocal support; they included Mortimer's sons, Edward, Roger and John. Sir William Trussell was appointed procurator

Procurator (with procuracy or procuratorate referring to the office itself) may refer to:

* Procurator, one engaged in procuration, the action of taking care of, hence management, stewardship, agency

* ''Procurator'' (Ancient Rome), the title o ...

, or Speaker, despite his not being an elected member of parliament. Although the office of procurator was not new, the purpose of Trussell's role set a constitutional precedent, as he was authorised to speak on behalf of parliament as a body. A chronicle describes Trussell as one "who cannot disagree with himself and, herefore shall ordain for all". There were fewer lords present than were traditionally summoned, which increased the influence of the Commons. This may have been a deliberate strategy on behalf of Isabella and Mortimer, who, suggests Dodd, would have known well that in the occasionally tumultuous parliaments of earlier reigns, "the trouble that had been caused in parliament had emanated almost exclusively from the barons". The Archbishop of York, who had been summoned to the December parliament, was "conspicuous by his absence" from the January sitting. Some Welsh MPs also received summonses, but these had deliberately been despatched too late for those elected to attend; others, such as the sheriff

A sheriff is a government official, with varying duties, existing in some countries with historical ties to England where the office originated. There is an analogous, although independently developed, office in Iceland that is commonly transla ...

of Meirionnydd

Meirionnydd is a coastal and mountainous region of Wales. It has been a kingdom, a cantref, a district and, as Merionethshire, a county.

Kingdom

Meirionnydd (Meirion, with -''ydd'' as a Welsh suffix of land, literally ''Land adjoined to Meirio ...

, Gruffudd Llwyd

Gruffudd Llwyd (fl. c.1380–1410) was a Welsh language poet.

Gruffudd was the nephew of the poet Hywel ab Einion Lygliw and the bardic tutor of Rhys Goch Eryri.

Gruffudd composed poems on themes of love and religion. His surviving work is cha ...

, refused to attend, out of loyalty to Edward II and also hatred of Roger Mortimer.

Although a radical gathering, the parliament was to some degree consistent with previous assemblies, being dominated by lords reliant on a supportive Commons. It differed, though, in the greater-than-usual influence that outsiders and commoners had, such as those from London. The January–February parliament was geographically broader too, as it contained unelected members from Bury St Edmunds and St Albans: says Maddicott, "those who planned the deposition reached out in parliament to those who had no right to be there". And, says Dodd, the rebels deliberately made parliament "centre stage" to their plans.

Parliament assembled

The King's absence

Before parliament met, the lords had sent

Before parliament met, the lords had sent Adam Orleton

Adam Orleton (died 1345) was an English churchman and royal administrator.

Life

Orleton was born into a Herefordshire family, possibly in Orleton, possibly in Hereford. The lord of the manor was Roger Mortimer, to whose interests Orleton was lo ...

(the Bishop of Hereford) and William Trussell to Kenilworth to see the King, with the intention of persuading Edward to return with them and attend parliament. They failed in this mission: Edward flatly refused and roundly cursed them. The envoys returned to Westminster on 12 January; by which time parliament had been sitting five days. It was felt that nothing could be done until the King had arrived: historically a parliament could only pass statutes with the monarch present. On hearing from Orleton and Trussell how Edward had denounced them, the King's opponents were no longer willing to let his absence stand in their way. Edward II's refusal to attend failed to prevent the parliament from taking place, the first time this had ever happened.

Constitutional crisis

The various titles bestowed on the younger Edward at the end of 1326—which acknowledged his unique position in government while avoiding calling him king—reflected an underlyingconstitutional crisis

In political science, a constitutional crisis is a problem or conflict in the function of a government that the political constitution or other fundamental governing law is perceived to be unable to resolve. There are several variations to this ...

, of which contemporaries were keenly aware. The fundamental question was how the crown was transferred between two living kings, a situation which had never arisen before. Valente has described how this "upset the accepted order of things, threatened the sacrosanctity of kingship, and lacked clear legality or established process". Contemporaries were also uncertain as to whether Edward II had abdicated or was being deposed. On 26 October it had been recorded in the Close Roll

The Close Rolls () are an administrative record created in medieval England, Wales, Ireland and the Channel Islands by the royal chancery, in order to preserve a central record of all letters close issued by the chancery in the name of the Crown ...

s that Edward had "left or abandoned his kingdom", and his absence enabled Isabella and Mortimer to rule. They could legitimately argue that King Edward, having provided no regent during his absence (as would be usual), should make his son governor of the kingdom in his father's stead. They also said Edward II held Parliament in contempt by calling it a treasonous assembly and insulted those attending it as traitors". It is unknown whether the King did, in fact, say or believe this, but it certainly suited Isabella and Mortimer for parliament to think so. If Edward did denounce parliament then he probably did not realise how it could be used against him. In any case, Edward's absence saved the couple the embarrassment of having a reigning king present when they deposed him, and Seymour Phillips suggests that if Edward had attended he may have found enough support to disrupt their plans.

Proceedings of Monday, 12 January

Parliament had to consider its next step. Bishop Orleton—emphasising Isabella's fear of the King—asked the assembled lords whom they would prefer to rule, Edward or his son. The response was sluggish, with no rush to either depose or acclaim. Deposition had been raised too suddenly for many members to stomach: the King was still not entirely friendless, and indeed, has been described by Paul Dryburgh as casting an "ominous shadow" over the proceedings. Orleton suspended proceedings until the next day to allow the lords to dwell on the question overnight. Also on the 12th, Sir Richard de Betoyne, theMayor of London

The mayor of London is the chief executive of the Greater London Authority. The role was created in 2000 after the Greater London devolution referendum in 1998, and was the first directly elected mayor in the United Kingdom.

The current m ...

, and the Common Council wrote to the lords in support of both the Earl of Chester being made King and the deposition of Edward II, whom they accused of failing to uphold his coronation oath and the duties of the crown. Mortimer, who was highly regarded by Londoners, may well have instigated this as a means of influencing the lords. The Londoners' petition also proposed that the new king should be governed by his Council

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/ shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or nati ...

until it was clear he understood his coronation oath and regal responsibilities. This petition the lords accepted; another, requesting the King should hold Westminster parliaments annually until he reached his majority

A majority, also called a simple majority or absolute majority to distinguish it from related terms, is more than half of the total.Dictionary definitions of ''majority'' aMerriam-WebsterGuildhall

A guildhall, also known as a "guild hall" or "guild house", is a historical building originally used for tax collecting by municipalities or merchants in Great Britain and the Low Countries. These buildings commonly become town halls and in some ...

where they swore an oath "to uphold all that has been ordained or shall be ordained for the common profit". This was intended to present those in parliament who disagreed with deposition with a ''fait accompli''. At the Guildhall they also swore to uphold the constitutional limitations of the Ordinances of 1311

The Ordinances of 1311 were a series of regulations imposed upon King Edward II by the peerage and clergy of the Kingdom of England to restrict the power of the English monarch. The twenty-one signatories of the Ordinances are referred to as the L ...

.

The group then returned to Westminster in the afternoon, and the lords formally acknowledged that Edward II was no longer to be King. Several orations were made. Mortimer, speaking on behalf of the lords, announced their decision. Edward II, he proclaimed, would abdicate and "...Sir Edward ... should have the government of the realm and be crowned king". The French chronicler Jean Le Bel described how the lords proceeded to document Edward II's "ill-advised deeds and actions" to create a legal record which was duly presented to parliament. This record declared "such a man was unfit ever to wear the crown or call himself King". This list of misdeeds—probably drawn up by Orleton and Stratford personally—were known as the Articles of Accusation. The bishops gave sermons—Orleton, for example, spoke of how "a foolish king shall ruin his people", and, report Dunham and Wood, he "dwelt weightily upon the folly and unwisdom of the king, and upon his childish doings". This, says Ian Mortimer, was "a tremendous sermon, rousing those present in the way he knew best, through the power of the word of God". Orleton based his sermon on the biblical text "Where there is no governor the people shall fall" from the Book of Proverbs

The Book of Proverbs ( he, מִשְלֵי, , "Proverbs (of Solomon)") is a book in the third section (called Ketuvim) of the Hebrew Bible and a book of the Christian Old Testament. When translated into Greek and Latin, the title took on differen ...

, while the Archbishop of Canterbury took for his text ''Vox Populi, Vox Dei

''Vox Populi, Vox Dei'' is a Whig tract of 1709, titled after a Latin phrase meaning "the voice of the people is the voice of God". It was expanded in 1710 and later reprintings as ''The Judgment of whole Kingdoms and Nations: Concerning the Ri ...

''.

Articles of accusation

During the sermons, the articles of deposition were officially presented to the assembly. In contrast to the elaborate and floridly hyperbolic accusations previously launched at the Despensers, this was a relatively simple document. The King was accused of being incapable of fair rule; of indulging false counsellors; preferring his own amusements to good government; neglecting England and losing Scotland; dilapidating the church and imprisoning the clergy; and, all in all, being in fundamental breach of the coronation oath he had made to his subjects. All of which, the rebels claimed, was so well known as to be undeniable. The articles accused Edward's favourites of tyranny although not the King himself, whom they described as "incorrigible, without hope of reform". England's succession of military failures in Scotland and France rankled with the lords: Edward had fought no successful campaigns in either theatre, yet had raised enormous levies to enable him to do so. Such levies says

During the sermons, the articles of deposition were officially presented to the assembly. In contrast to the elaborate and floridly hyperbolic accusations previously launched at the Despensers, this was a relatively simple document. The King was accused of being incapable of fair rule; of indulging false counsellors; preferring his own amusements to good government; neglecting England and losing Scotland; dilapidating the church and imprisoning the clergy; and, all in all, being in fundamental breach of the coronation oath he had made to his subjects. All of which, the rebels claimed, was so well known as to be undeniable. The articles accused Edward's favourites of tyranny although not the King himself, whom they described as "incorrigible, without hope of reform". England's succession of military failures in Scotland and France rankled with the lords: Edward had fought no successful campaigns in either theatre, yet had raised enormous levies to enable him to do so. Such levies says F. M. Powicke

Sir Frederick Maurice Powicke (1879–1963) was an English medieval historian. He was a fellow of Merton College, Oxford and was a professor at Queen's University, Belfast and the Victoria University of Manchester, and from 1928 until his re ...

, "could only have been justified by military success". Accusations of military failure were not wholly fair in placing the blame for these losses, as they did, so squarely on Edward II's shoulders: Scotland had arguably been almost lost in 1307. Edward's father had, says Seymour Phillips, left him "an impossible task", having started the war without making sufficient gains to allow his son to finish it. And Ireland had been the theatre of one of the King's few military successes—the English victory at the Battle of Faughart in 1318 had crushed Robert the Bruce

Robert I (11 July 1274 – 7 June 1329), popularly known as Robert the Bruce (Scottish Gaelic: ''Raibeart an Bruis''), was King of Scots from 1306 to his death in 1329. One of the most renowned warriors of his generation, Robert eventuall ...

's ambitions in Ireland (and seen the death of his brother). Only the King's military failures, though, were remembered, and indeed, they were the most damning of all the articles:

The King deposed

Every speaker on 13 January reiterated the articles of accusation, and all concluded by offering the young Edward as king, if the people approved him. The crowd outside, which included a large company of unruly Londoners, says Valente, had been "whipped ... into such fervour" by "dramatic outcries at appropriate points in the orations" from Thomas Wake, who repeatedly rose and demanded of the assembly whether they agreed with each speaker; "Do you agree? Do the people of the country agree?" Wake's exhortations—arms outstretched, says Prestwich, he cried "I say for myself that he shall reign no more")—combined with the intimidating mob, led to tumultuous responses of "Let it be done! Let it be done!" This, says May McKisack, gave the new regime a degree of "support of popular clamour". The Londoners played a key role in ensuring that remaining supporters of Edward II were intimidated and overwhelmed by events. Edward III was proclaimed king. At the end of the day, said Valente, "the ''electio'' of the magnates received the ''acclamatio'' of the ''populi'', Fiat!'',." Proceedings drew to a close with a chorus of '' Gloria, laus et honor'', and perhaps oaths of homage from the lords to the new king. Assent to the new regime was not universal: the Bishops ofLondon

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, Rochester and Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers Eden, Caldew and Petteril. It is the administrative centre of the City ...

abstained from the day's affairs in protest, and Rochester was later beaten up by a London mob because of his opposition.

The King's response

One final action remained to be taken: the ex-King in Kenilworth had to be informed that his subjects had chosen to withdraw their allegiance from him. A delegation was organised to take the news. The delegates were the Bishops of Ely, Hereford and London, and around 30 laymen. Among the latter, the Earl of Surrey represented the lords and Trussell represented the shire knights. The group was intended to be as representative of parliament—and so the kingdom—as possible. It was not composed solely of parliamentarians, but there were enough of them in it to appear parliamentarian. Its size also had the added advantage of spreading collective responsibility far more broadly than would have happened in a small group. They left on or shortly after Thursday 15 January and had arrived in Kenilworth by either 21 or 22 January, when William Trussell asked for the King to be brought to them in the name of parliament. Edward, dressed in a black gown and under the Earl of Lancaster's escort, was brought to thegreat hall

A great hall is the main room of a royal palace, castle or a large manor house or hall house in the Middle Ages, and continued to be built in the country houses of the 16th and early 17th centuries, although by then the family used the gr ...

. Geoffrey le Baker's Chronicle describes how the delegates equivocated at first, "adulterating the word of truth" before coming to the point. Edward was offered the choice of resigning in favour of his son, and being provided for according to his rank, or of being deposed. This, it was emphasised, could lead to the throne being offered to someone, not of royal blood but politically experienced, clearly referring to Mortimer. The King protested—mildly—and wept, fainting at one point. According to Orleton's later report, Edward claimed he had always followed the guidance of his nobles, but regretted any harm he had done. The deposed king took comfort from his son succeeding him. It seems probable that a memorandum of acknowledgement was drawn up between the delegation and Edward, minuting what was said, although this has not survived. Baker says that at the end of the meeting Edward's Steward

Steward may refer to:

Positions or roles

* Steward (office), a representative of a monarch

* Steward (Methodism), a leader in a congregation and/or district

* Steward, a person responsible for supplies of food to a college, club, or other ins ...

, Thomas Blunt, dramatically broke his staff of office

A staff of office is a staff, the carrying of which often denotes an official's position, a social rank or a degree of social prestige.

Apart from the ecclesiastical and ceremonial usages mentioned below, there are less formal usages. A gold- o ...

in half, and dismissed Edward's household

A household consists of two or more persons who live in the same dwelling. It may be of a single family or another type of person group. The household is the basic unit of analysis in many social, microeconomic and government models, and is i ...

.

The delegation left Kenilworth for London on 22 January: their news preceded them. By the time they reached Westminster, around 25 January, Edward III was already officially referred to as king, and his peace

Peace is a concept of societal friendship and harmony in the absence of hostility and violence. In a social sense, peace is commonly used to mean a lack of conflict (such as war) and freedom from fear of violence between individuals or groups. ...

had been proclaimed at St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglicanism, Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London ...

on the 24th. Now the new king could be proclaimed in public; Edward III's reign was thus dated from 25 January 1327. Behind the scenes, though, discussions must have begun on the thorny question of what to do with his predecessor, who still had not had any judgement—legal or parliamentary—passed upon him.

Subsequent events and aftermath

Recall of parliament

Edward III's political education was deliberately accelerated by the tutelage of advisors such asWilliam of Pagula William of Pagula (died 1332), also known as William Paull or William Poull, was a 14th-century English canon lawyer and theologian best known for his written works, particularly his manual for priests entitled the '' Oculus Sacerdotis''. Pagula was ...

and Walter de Milemete. Still a minor, Edward III was crowned at Westminster Abbey on 1 February 1327: executive power remained with Mortimer and Isabella. Mortimer was made Earl of March

Earl of March is a title that has been created several times in the Peerage of Scotland and the Peerage of England. The title derived from the "marches" or borderlands between England and either Wales ( Welsh Marches) or Scotland ( Scottish ...

in October 1328, but otherwise, received few grants of land or money. Isabella, on the other hand, gained an annual income of 20,000 marks ( £13,333) within the month. She achieved this by requesting the return of her dower

Dower is a provision accorded traditionally by a husband or his family, to a wife for her support should she become widowed. It was settled on the bride (being gifted into trust) by agreement at the time of the wedding, or as provided by law. ...

which her husband had confiscated; it was returned to her substantially augmented. Ian Mortimer has called the grant she received as amounting to "one of the largest personal incomes anyone had ever received in English history". Following Edward's coronation parliament was recalled. According to precedent, a new parliament should have been summoned with the accession of a new monarch, and this failure of process indicates the novelty of the situation. Official records regnally date the entire parliament to the first year of Edward III's reign rather than the last of his father's, even though it spread over both.

When recalled, parliament returned to its usual business, and heard a large number (42) of petitions from the community. These not only included the political—and often lengthy—petitions related directly to the deposition, but a similar number coming from the clergy and the City of London. This was the greatest number of petitions to have been submitted by the Commons in the history of parliament. Their requests ranged from confirmation of the acts against the Despensers and those in favour of Thomas of Lancaster, to the reconfirmation of the Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by t ...

. There were ecclesiastical petitions, and those from the shires dealt mainly in annulling debts and amercement

An amercement is a financial penalty in English law, common during the Middle Ages, imposed either by the court or by peers. The noun "amercement" lately derives from the verb to amerce, thus: the king amerces his subject, who offended some law. T ...

s of both individuals and towns. There were numerous requests for the King's grace, for example, overturning perceived false judgements in local courts and concerns for law and order in the localities generally. Restoring law and order was a priority of the new regime, as Edward II's reign had foundered on his inability to do so, and his failure then used to depose him. The principle behind Edward's deposition was, supposedly, to redress such wrongs his reign had caused. One petition requested members of the Commons be authorised to take written confirmation of their petition and its concomitant answer to their localities, while another protested against corrupt local royal officials. This eventually resulted in a proclamation

A proclamation (Lat. ''proclamare'', to make public by announcement) is an official declaration issued by a person of authority to make certain announcements known. Proclamations are currently used within the governing framework of some nations ...

in 1330 instructing individuals who had cause of complaint or need of redress from such should attend the approaching parliament.

The Commons too were concerned for the restoration of law and order, and one of their petitions called for the immediate appointment of wide-ranging keepers of the peace who could personally put men on trial. This request was agreed by the King's council. This return to normal parliamentary business demonstrated, it was hoped, both the regime's legitimacy and its ability to repair the injustices of the previous reign. Most of the petitions were accepted—resulting in seventeen statute articles—which indicates how keen Isabella and Mortimer were to placate the Commons. When parliament finally dissolved on 9 March 1327, it had been the second longest, at seventy-one days, of the century to date; further, notes Dodd, because of this it was "the only assembly in the late medieval period to outlive a king and see in his successor".

The dead Earl of Lancaster's titles and estates were restored to his brother Henry, and the 1323 judgement against Mortimer, which exiled him, was overturned. The invaders were also restored to their estates in Ireland. In an attempt at settling the Irish situation, parliament issued ordinances on 23 February pardoning those who had supported Robert Bruce's invasion. The deposed King was referred to only obliquely in official records—for example, as "Edward his father, when he was king," "Edward, the father of the King who now is" or as he had been known as a youth, "Edward of Caernarfon". Isabella and Mortimer were careful to try to prevent the deposition from tarnishing their reputations, reflected in their concern of not just obtaining Edward II's ''ex-post facto'' agreement to his removal, but then publicising his agreement. The problem they faced was that this effectively involved having to rewrite a piece of history in which many people were actively involved and had taken place only two weeks earlier.

The City of London also benefited. In 1321, Edward II had disenfranchised London, and royal officials, in the words of a contemporary, had "pris devery privilege and penny out of the city", as well as deposing their mayor: Edward had ruled London himself through a system of wardens. Gwyn Williams described this as "an emergency regime of dubious legality". In 1327 Londoners petitioned the recalled parliament for their liberties to be restored, and, since they had been of valuable—probably crucial—importance in enabling the deposition, on 7 March they received not just the rights Edward II had removed from them, but greater privileges than they had ever possessed.

Later events

Meanwhile, Edward II was still imprisoned at Kenilworth, and was intended to stay there forever. Attempts to free him led to his transfer to the more secureBerkeley Castle

Berkeley Castle ( ; historically sometimes spelled as ''Berkley Castle'' or ''Barkley Castle'') is a castle in the town of Berkeley, Gloucestershire, United Kingdom. The castle's origins date back to the 11th century, and it has been desi ...

in early April 1327. Plotting continued, and he was frequently moved to other places. Eventually being returned to Berkeley for good, Edward died

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

there on the night of 21 September. Mark Ormrod described this as "suspiciously timely", for Mortimer, as Edward's almost-certain murder permanently removed a rival and a target for restoration.

Parliamentary proceedings were traditionally drawn up contemporaneously and entered onto a parliament roll by clerks. The Roll of 1327 is notable, according to the ''History of as Parliament'', because "despite the highly charged political situation in January 1327, tcontains no mention of the process by which Edward II ceased to be king". The roll only begins with the reassembling of parliament under Edward III in February, after the deposition of his father. It is likely, says Phillips, that since those involved were aware of the precarious legal basis for Edward's deposition—and how it would not bear "too close an examination"—there may never have been an enrolment: "Edward II had been airbrushed from the record". Other possible reasons for the lack of an enrolment are that it would never have been entered on a roll because the parliament was clearly illegitimate, or because Edward III later felt it was undesirable to have an official record of a royal deposition in case it suggested a precedent had been set, and removed it himself.

It was not long before the crisis affected Mortimer's relationship with Edward III. Notwithstanding Edward's coronation, Mortimer was the country's ''de facto'' ruler. The high-handed nature of his rule was demonstrated, according to Ian Mortimer, on the day of Edward III's coronation. Not only did he arrange for his three eldest sons to be knighted, but—feeling a knight's ceremonial robes were inadequate—he had them dressed as earls for the occasion. Mortimer himself occupied his energies in getting rich and alienating people, and the defeat of the English army by the Scots at the Battle of Stanhope Park

The Weardale campaign, part of the First War of Scottish Independence, occurred during July and August 1327 in Weardale, England. A Scottish force under James, Lord of Douglas, and the earls of Moray and Mar faced an English army commanded ...

(and the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton which followed it in 1328) worsened his position. Maurice Keen

Maurice Hugh Keen (30 October 1933 – 11 September 2012) was a British historian specializing in the Middle Ages. His father had been the Oxford University head of finance ('Keeper of the University Chest') and a fellow of Balliol College, Ox ...

describes Mortimer as being no more successful in the war against Scotland than his predecessor had been. Mortimer did little to rectify this situation and continued to show Edward disrespect. Edward, for his part, had originally (and unsurprisingly) sympathised with his mother against his father, but not necessarily for Mortimer. Michael Prestwich has described the latter as a "classic example of a man whose power went to his head", and compares Mortimer's greed to that of the Despensers and his political sensitivity to that of Piers Gaveston. Edward had married Philippa of Hainault in 1328, and they had a son in June 1330. Edward decided to remove Mortimer from the government: accompanied and assisted by close companions, Edward launched a coup d'état which took Mortimer by surprise at Nottingham Castle

Nottingham Castle is a Stuart Restoration-era ducal mansion in Nottingham, England, built on the site of a Norman castle built starting in 1068, and added to extensively through the medieval period, when it was an important royal fortress and ...

on 19 October 1330. He was hanged at Tyburn

Tyburn was a Manorialism, manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman roads to the west (modern Edgware Road) and sout ...

a month later and Edward III's personal reign began.

Scholarship

The parliament of 1327 is the focus of two main areas of interest for historians: in the long term, the part it played in the development of the English parliament, and in the short term, its place in the deposition of Edward II. On the first point, Gwilym Dodd has described the parliament as a landmark event in the institution's history, and, say Richardson and Sayles, it began a fifty-year period of developing and honing procedure. The assembly also, suggests G. L. Harriss, marks a point in the history of the English monarchy in which its authority was curtailed to a similar degree to the limitation previously imposed on King John by the Magna Carta and Henry III by de Montfort. Maddicott agrees with Richardson and Sayles regarding the significance of 1327 for the development of separate chambers, because it "saw the presentation of the first full set of commons' petitions ndthe first comprehensive statute to derive from such petitions". Maude Clarke described its significance as being in how "feudal defiance" was for the first time subsumed to the "will of the commonality, and the King was rejected not by his vassals but by his subjects". The second question it raises for scholars is whether Edward II was deposed by parliament, as an institution, or just while parliament sat. While many of the events necessary for the King's removal had taken place in parliament, others of equal significance (for example, the oath-taking at the Guildhall) occurred elsewhere. Parliament was certainly the public setting for the deposition. Victorian constitutional historians saw Edward's deposition as demonstrating fledgeling authority by the House of Commons akin to their ownparliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of th ...

. Twentieth-century historiography remains divided on the issue. Barry Wilkinson, for example, considered it a deposition—but by the magnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

s, rather than parliament—but G. L. Harriss termed it an abdication, believing "there was no legal process of deposition, and kings like ... Edward II were induced to resign". Edward II's position has been summed up as his being offered "the choice of abdication in favour of his son Edward or forcible deposition in favour of a new king selected by his nobles". Seymour Phillips has argued that it was the "combined determination of the leading magnates, their personal followers and the Londoners" that Edward should be gone.

Chris Bryant argues it is not clear whether these events were driven by parliament, or merely happened to occur in parliament, although he suggests Isabella and Roger Mortimer thought it necessary to have parliamentary support. Valente has suggested "the deposition was not revolutionary and did not attack kingship itself", it was not "necessarily illegal and outside the bounds of the 'constitution'", even though historians commonly describe it as such. The discussion is confused further, she says, because varying descriptions are given of the assembly by contemporaries. Some described it as being a royal council, others called it a parliament in the King's absence or a parliament with the Queen presiding, or one summoned by her and Prince Edward. Ultimately, she wrote, it was magnates deciding on policy, and being able to do so through the support of the knights and commoners.

Dunham and Wood suggested that Edward's deposition was forced by political rather than legal factors. There is also a choice of who deposed: whether "the magnates alone deposed, that the magnates and people jointly deposed, that Parliament itself deposed, even that it was the 'people' whose voice was decisive". Ian Mortimer has described how "the representatives of the community of the realm would be called upon to act as an authority over and above that of the King". It was no advance of democracy, and was not intended to be—its purpose was to "unite all classes of the realm against the monarch" of the time. John Maddicott has said the proceedings began as a baronial coup but ended up becoming something close to a "national plebiscite", in which the commons were part of a radical reform of the state. This parliament also clarified procedures, such as codifying petitioning, legislating for it, and promulgating statutes, which would become the norm.

The parliament also illustrates how contemporaries viewed the nature of tyranny. The leaders of the revolution, aware that deposition was a barely understood and unpopular concept in the political culture of the day, began almost immediately re-casting events as an abdication instead. Few contemporaries overtly disagreed with Edward's deposition, "but the fact of deposition itself caused immense anxiety", suggested David Matthews. It was an event as yet unheard of in English history. Phillips comments that "using accusations of tyranny to remove a legitimate and anointed king were too contentious and divisive to be of any practical use", which is why Edward had been accused of incompetence and inadequacy and much else, and not of tyranny. The Brut Chronicle

The ''Brut'' Chronicle, also known as the Prose ''Brut'', is the collective name of a number of medieval chronicles of the history of England. The original Prose ''Brut'' was written in Anglo-Norman; it was subsequently translated into Latin and E ...

, in fact, goes so far as to ascribe Edward's deposition, not to intentions of men and women, but to the fulfilment of a prophecy

In religion, a prophecy is a message that has been communicated to a person (typically called a ''prophet'') by a supernatural entity. Prophecies are a feature of many cultures and belief systems and usually contain divine will or law, or p ...

by Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and leg ...

.

Edward's deposition also set a precedent and laid out arguments for subsequent depositions. The 1327 articles of accusation, for example, were drawn on sixty years later during the series of crises between King Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father d ...

and the Lords Appellant. When Richard refused to attend parliament in 1386, Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester and William Courtenay, Archbishop of Canterbury visited him at Eltham Palace

Eltham Palace is a large house at Eltham ( ) in southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich. The house consists of the medieval great hall of a former royal residence, to which an Art Deco extension was added in the 1930 ...

and reminded him how—per "the statute by which Edward Ihad been adjudged"—a King who did not attend parliament was liable to deposition by his lords.

Indeed, it has been suggested Richard II may have been responsible for the disappearance of the 1327 parliament roll when he recovered personal power two years later. Given-Wilson says that Richard considered Edward's deposition a "stain which he was determined to remove" from the royal family's history by proposing Edward's canonisation. Richard's subsequent deposition by

Indeed, it has been suggested Richard II may have been responsible for the disappearance of the 1327 parliament roll when he recovered personal power two years later. Given-Wilson says that Richard considered Edward's deposition a "stain which he was determined to remove" from the royal family's history by proposing Edward's canonisation. Richard's subsequent deposition by Henry Bolingbroke

Henry IV ( April 1367 – 20 March 1413), also known as Henry Bolingbroke, was King of England from 1399 to 1413. He asserted the claim of his grandfather King Edward III, a maternal grandson of Philip IV of France, to the Kingdom of Fran ...

in 1399 naturally drew direct parallels with that of Edward. Events which had taken place over 70 years earlier were by 1399 considered "ancient custom", which had set legal precedent

A precedent is a principle or rule established in a previous legal case that is either binding on or persuasive for a court or other tribunal when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts. Common-law legal systems place great valu ...

, if an ill-defined one. A prominent chronicle of Henry's usurpation, composed by Adam of Usk

Adam of Usk ( cy, Adda o Frynbuga, c. 1352–1430) was a Welsh priest, canonist, and late medieval historian and chronicler. His writings were hostile to King Richard II of England.

Patronage

Born at Usk in what is now Monmouthshire (Sir Fynwy), ...

, has been described as bearing "a striking resemblance" to the events of the 1327 parliament. Indeed, said Gaillard Lapsley, "Adam uses words that strongly suggest that he had this precedent in mind."

Edward II's deposition was used as political propaganda as late as the troubled last years of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

in the 1620s. The King was very ill and played a peripheral role in government; his favourite, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham became proportionately more powerful. Attorney general