Parliament Of The Cape Of Good Hope on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope functioned as the legislature of the

The Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope functioned as the legislature of the

Prior to responsible government, the

Prior to responsible government, the

Among the Cape's powerful local leaders, a radical faction under the leadership of

Among the Cape's powerful local leaders, a radical faction under the leadership of

From the beginning of Responsible Government, there were increasingly vocal complaints from members of parliament about the humble appearance of their venue. MPs increasingly complained that the Parliament would not attract sufficient respect from "the public and strangers", unless a more grandiose edifice were constructed.

A brief controversy arose about this need to build a more stately Parliament, as Prime Minister Molteno was not an ostentatious man, and had little interest in spending tax money on what he saw as essentially an expensive vanity project (At the time an enormous countrywide programme was underway, of building schools, public transport and communications infrastructure, and funds were consequently in tight demand). He was over-ruled by the legislature however, and the Commissioner of Public Works,

From the beginning of Responsible Government, there were increasingly vocal complaints from members of parliament about the humble appearance of their venue. MPs increasingly complained that the Parliament would not attract sufficient respect from "the public and strangers", unless a more grandiose edifice were constructed.

A brief controversy arose about this need to build a more stately Parliament, as Prime Minister Molteno was not an ostentatious man, and had little interest in spending tax money on what he saw as essentially an expensive vanity project (At the time an enormous countrywide programme was underway, of building schools, public transport and communications infrastructure, and funds were consequently in tight demand). He was over-ruled by the legislature however, and the Commissioner of Public Works,

Over the years, as the Cape's early generation of political heavy-weights died or retired, power moved away from their liberal heirs, and towards

Over the years, as the Cape's early generation of political heavy-weights died or retired, power moved away from their liberal heirs, and towards

In the early twentieth century, following the tumults of the

In the early twentieth century, following the tumults of the

The parliament's executive governments ("Ministries") dated only from 1872, when the Cape first attained

The parliament's executive governments ("Ministries") dated only from 1872, when the Cape first attained

For much of the Cape's history, the parliament operated without formal political parties. Instead, parliamentarians aligned temporarily – according to specific issues. Nonetheless, informal alliances began to form according to the constituencies' overall attitude to long-standing issues, such as

For much of the Cape's history, the parliament operated without formal political parties. Instead, parliamentarians aligned temporarily – according to specific issues. Nonetheless, informal alliances began to form according to the constituencies' overall attitude to long-standing issues, such as  In the 1860s and early 70s, an alliance of parliamentarians came together in support of "

In the 1860s and early 70s, an alliance of parliamentarians came together in support of "

Two key events contributed to the rise of political parties. The first was the 1878 annexation of the Transvaal and the ensuing

Two key events contributed to the rise of political parties. The first was the 1878 annexation of the Transvaal and the ensuing  The remaining liberal "westerners" formed the " South African Party" but were too weak to oppose Rhodes's Progressives alone, and so allied with the Afrikaner Bond to fight Rhodes's dominance. This controversial alliance with the racist Bond caused many of the South African Party's black voters to abandon it. It came to power briefly under its liberal leader William Schreiner but overall the ensuing decades were dominated by the Progressive Party.

In 1908, John X Merriman finally led the South African Party to electoral victory, a mere two years before the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910.

The remaining liberal "westerners" formed the " South African Party" but were too weak to oppose Rhodes's Progressives alone, and so allied with the Afrikaner Bond to fight Rhodes's dominance. This controversial alliance with the racist Bond caused many of the South African Party's black voters to abandon it. It came to power briefly under its liberal leader William Schreiner but overall the ensuing decades were dominated by the Progressive Party.

In 1908, John X Merriman finally led the South African Party to electoral victory, a mere two years before the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910.

The Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope functioned as the legislature of the

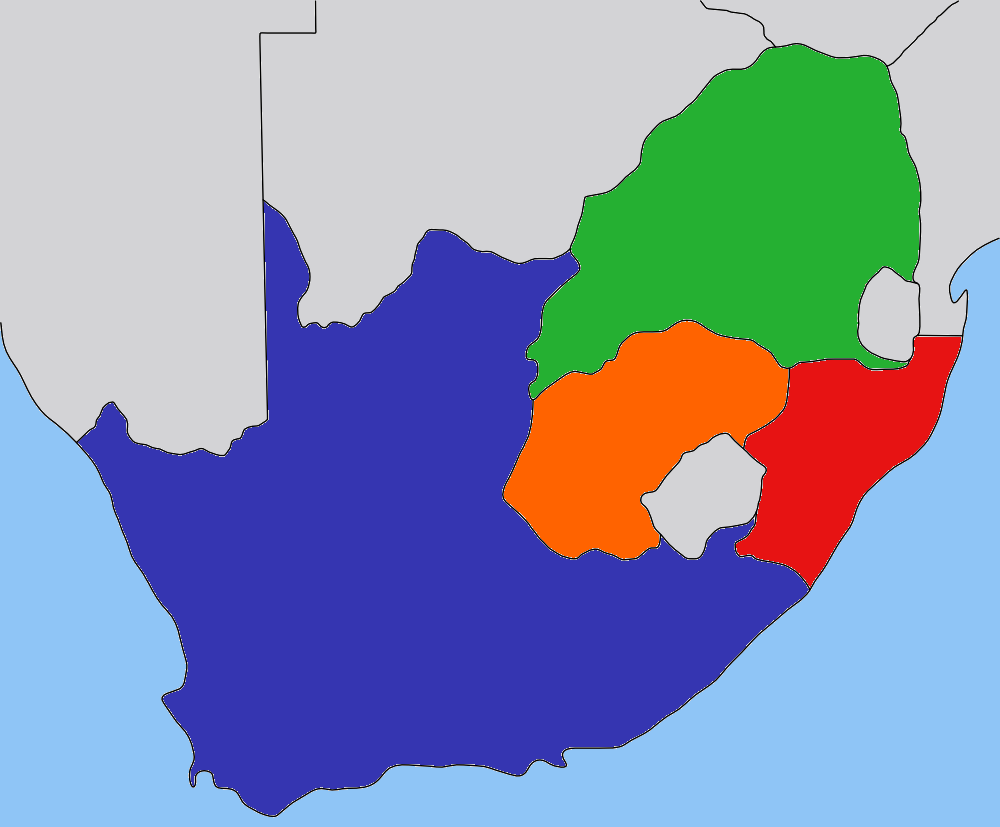

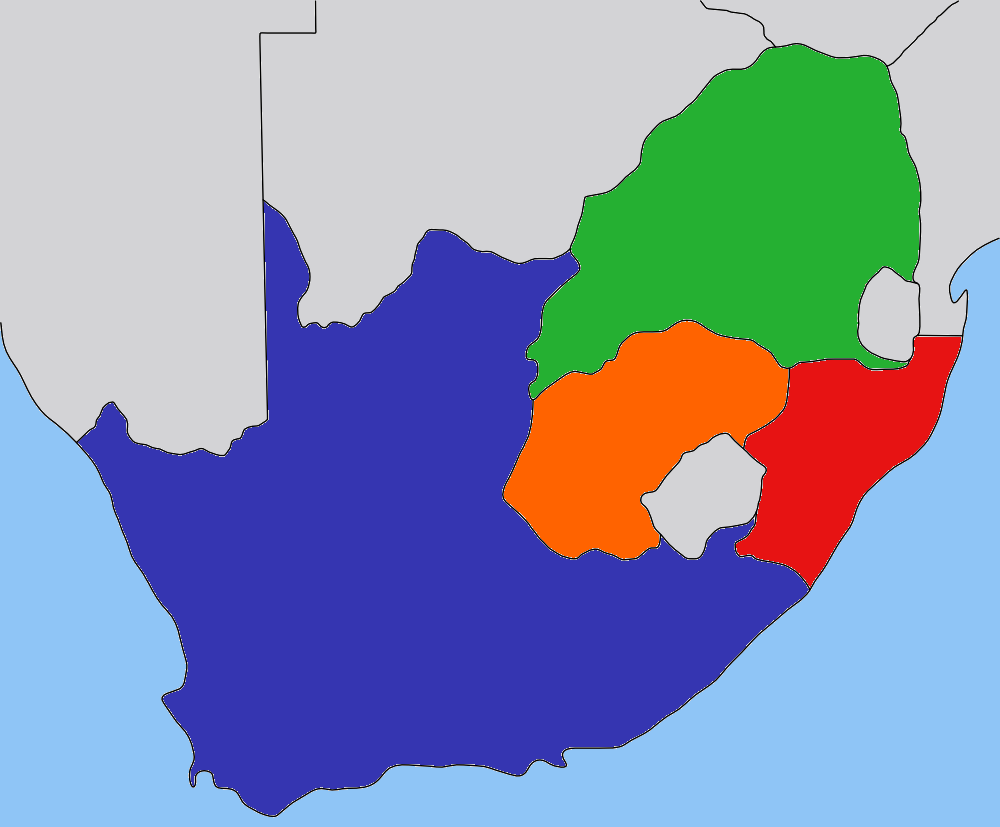

The Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope functioned as the legislature of the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

, from its founding in 1853, until the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, when it was dissolved and the Parliament of South Africa

The Parliament of the Republic of South Africa is South Africa's legislature; under the present Constitution of South Africa, the bicameral Parliament comprises a National Assembly and a National Council of Provinces. The current twenty-seve ...

was established. It consisted of the House of Assembly

House of Assembly is a name given to the legislature or lower house of a bicameral parliament. In some countries this may be at a subnational level.

Historically, in British Crown colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony adm ...

(the lower house) and the legislative council (the upper house).

The First Parliament

Prior to responsible government, the

Prior to responsible government, the British government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_est ...

granted the Cape Colony a rudimentary and relatively powerless Legislative Council in 1835.

The British attempt to turn the Cape into a penal colony for convicts, similar to Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

, mobilised the local population in the 1840s and threw up a generation of local leaders who believed that far-away Britain was not capable of understanding local interests and issues. This group of politicians, which included the likes of Porter, Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

, Fairbairn, Molteno

Molteno (; lmo, label= Brianzöö, Mültée) is a '' comune'' (municipality) and a hill-top town in the Province of Lecco in the Italian region Lombardy, located about northeast of Milan and about southwest of Lecco. As of 31 December 2004, it ...

, Stockenström and Jarvis, shared not only a common belief in the importance of local self-government, but also an explicit commitment to a liberal, inclusive and multi-racial political system.

This political elite successfully began the controversial drive for Cape independence which, unusually, was attained in the end through gradual evolution, rather than sudden revolution.

Representative Government (1853)

The Queen granted the Cape its first Parliament in 1853, and the local leadership were permitted to draft a constitution. This was a relatively liberal document that prohibited race or class discrimination, and instituted the non-racialCape Qualified Franchise

The Cape Qualified Franchise was the system of non-racial franchise that was adhered to in the Cape Colony, and in the Cape Province in the early years of the Union of South Africa. Qualifications for the right to vote at parliamentary elections ...

, whereby the same qualifications for suffrage were applied equally to all males, regardless of race. The pre-existing Legislative Council became the upper house of the new parliament, and was elected according to the two main provinces of that Cape at the time. A new lower house, the Assembly, was also constituted. However, the parliament was weak and executive power remained firmly in the hands of the Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

who was appointed from London.

The Governor opened this first parliament at his residence, "the Tuynhuys

De Tuynhuys (Garden House) is the Cape Town office of the president of South Africa.

The building

The building has in various guises been associated with the seat of the highest political authority in the land for almost two and a half cent ...

", but the House of Assembly soon relocated to the small but stately Goede Hoop Masonic Lodge buildings. The old Legislative Council (now reconstituted as the Parliament's upper house) was housed at the nearby Old Supreme Court building (now the Iziko Slave Lodge Museum).

Responsible Government (1872)

Among the Cape's powerful local leaders, a radical faction under the leadership of

Among the Cape's powerful local leaders, a radical faction under the leadership of John Molteno

Sir John Charles Molteno (5 June 1814 – 1 September 1886) was a soldier, businessman, champion of responsible government and the first Prime Minister of the Cape Colony.

Early life

Born in London into a large Anglo-Italian family, Molten ...

pushed for further independence in the form of "Responsible Government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

". This was attained in 1872, after a political struggle that lasted a decade. "Responsible Government" brought all branches of the Cape's government under local control by making the Executive directly "responsible" to Parliament and electorate for the first time.

There followed a brief boom period in the history of the Cape, with the economy surging, the frontiers stable and local democracy taking root.

The new constitution held the non-racial nature of its political system as one of its core values. The universal qualification for suffrage (£25) was sufficiently low to ensure that most owners of any form of property or land could vote; and there was a determination on the part of the Government not to raise it, on the understanding that rising levels of wealth would eventually render it obsolete. There were the early beginnings of a drive to register the many new potential voters, particularly the rural Xhosa people

The Xhosa people, or Xhosa-speaking people (; ) are African people who are direct kinsmen of Tswana people, Sotho people and Twa people, yet are narrowly sub grouped by European as Nguni ethnic group whose traditional homeland is primarily t ...

of the frontier region, who were mostly communal land owners and therefore eligible for suffrage. Opportunistic politicians soon followed, to campaign for Black African voters.

The new government based itself in the halls of the Masonic Lodge where the previous parliaments had sat. This relatively humble building was seen as suitably central and close to the Legislative Council building.

The large gardens of the Lodge soon became a popular venue for the public, with concerts, theatre and finally the "South African International Exhibition

The South African International Exhibition held in Cape Town, Cape Colony was a world's fair held in 1877 which opened on 15 February by Henry Bartle Frere.

Location

The exhibition was held in the grounds of the Lodge de Goede Hoop which was ...

" which Molteno

Molteno (; lmo, label= Brianzöö, Mültée) is a '' comune'' (municipality) and a hill-top town in the Province of Lecco in the Italian region Lombardy, located about northeast of Milan and about southwest of Lecco. As of 31 December 2004, it ...

sponsored in 1877.

The Parliamentary hall itself was open to members of the public, also explicitly ''"irrespective of class or colour"'', should they wish to observe the performance of their representatives.

The operating language of the parliament in the early years of Responsible Government was English, though Afrikaans was often spoken informally. Dutch was added by parliamentary act in 1882, by MP "Onze Jan" Hofmeyr with the powerful support of Saul Solomon. A statement was also made, on its introduction, that the recognition of a "Native" language, as a third official language, would also be acceptable, but only once sufficient "Native" parliamentarians were elected.

The new Parliament building

The building fiasco

From the beginning of Responsible Government, there were increasingly vocal complaints from members of parliament about the humble appearance of their venue. MPs increasingly complained that the Parliament would not attract sufficient respect from "the public and strangers", unless a more grandiose edifice were constructed.

A brief controversy arose about this need to build a more stately Parliament, as Prime Minister Molteno was not an ostentatious man, and had little interest in spending tax money on what he saw as essentially an expensive vanity project (At the time an enormous countrywide programme was underway, of building schools, public transport and communications infrastructure, and funds were consequently in tight demand). He was over-ruled by the legislature however, and the Commissioner of Public Works,

From the beginning of Responsible Government, there were increasingly vocal complaints from members of parliament about the humble appearance of their venue. MPs increasingly complained that the Parliament would not attract sufficient respect from "the public and strangers", unless a more grandiose edifice were constructed.

A brief controversy arose about this need to build a more stately Parliament, as Prime Minister Molteno was not an ostentatious man, and had little interest in spending tax money on what he saw as essentially an expensive vanity project (At the time an enormous countrywide programme was underway, of building schools, public transport and communications infrastructure, and funds were consequently in tight demand). He was over-ruled by the legislature however, and the Commissioner of Public Works, Charles Abercrombie Smith

Sir Charles Abercrombie Smith (12 May 1834 – 1 May 1919) was a Cape Colony scientist, politician and civil servant.

Early life

Charles Abercrombie Smith was born on 12 May 1834 in St Cyrus, Kincardineshire, Scotland, and studied physics and m ...

, ordered a select committee to receive designs.

The committee selected the elaborate proposal of the renowned architect , at the time an officer in the Public Works Department. Sites that were mooted for the new building included Greenmarket Square

Greenmarket Square is a historical square in the centre of old Cape Town, South Africa. The square was built in 1696, when a burgher watch house was erected.

Over the years, the square has served as a slave market, a vegetable market, a parkin ...

, Caledon Square and the top of Government Avenue, but eventually the current site was selected. Freeman was made resident architect and construction began on 12 May 1875, with Governor Henry Barkly laying the cornerstone.

Almost immediately it was discovered that Freeman's plans were faulty. Freeman's errors were compounded by the presence of groundwater, and a recalculation of the budget revealed that the actual costs would be many times the original figure that the government had allowed for.

The Cape government stepped in. Freeman was fired for incompetence and the Public Works Commission was re-structured. There was initially some discussion in parliament about abandoning the half-finished building. However, the government ordered the project completed, even though the budget was now calculated to be many times the original sum. In 1876 it appointed Henry Greaves to alter Freeman's plans, fix the faulty foundations, and see the project successfully through. Moreover, it ordered him to remove from the plan the statues, parapets, fountains, elaborate dome and other expensive flourishes.

Building re-commenced, but was delayed – this time by the British annexation of the Transvaal in 1878, the ensuing First Anglo-Boer War

The First Boer War ( af, Eerste Vryheidsoorlog, literally "First Freedom War"), 1880–1881, also known as the First Anglo–Boer War, the Transvaal War or the Transvaal Rebellion, was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881 betwee ...

, and finally by the building company going bankrupt in 1883. Greaves tenaciously completed the job however, and the large, stately, but relatively unpretentious building was finally opened in 1884.

Cape Prime Minister Thomas Scanlen, and Governor Henry Robinson led the opening ceremony in the building, declared finally to be worthy of the country's Legislature.

The restricting of the multi-racial franchise

Over the years, as the Cape's early generation of political heavy-weights died or retired, power moved away from their liberal heirs, and towards

Over the years, as the Cape's early generation of political heavy-weights died or retired, power moved away from their liberal heirs, and towards right-wing

Right-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that view certain social orders and Social stratification, hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this pos ...

opposition politicians who saw the multi-racial franchise as a threat to white political control.

This radical opposition had its origins in the white Eastern Cape separatist movement who had been threatened by the political mobilisation of their Xhosa neighbours. It gained office under Prime Minister Gordon Sprigg

Sir John Gordon Sprigg, (27 April 1830 – 4 February 1913) was an English-born colonial administrator, politician and four-time prime minister of the Cape Colony.

Early life

Sprigg was born in Ipswich, England, into a strongly Puritan fa ...

, and eventually reached the height of its power as the pro-imperialist " Progressive Party" under Prime Minister Cecil John Rhodes, the most dictatorial and aggressively expansionist leader in Cape history.

The liberals (now on the defensive, as the opposition " South African Party") attempted to further mobilise the Cape's Black population in a desperate attempt to find allies to the liberal & multi-racial cause. However they were outmanoeuvred by Rhodes and his allies, who imposed increasingly severe legal restrictions on the African franchise. As fast as the African voters mobilised, their numbers were diminished through discriminatory legislation.

The Parliamentary Registration Act (1887) removed traditional African forms of communal land-ownership from the franchise qualifications, thus disenfranchising a large portion of the Cape's Xhosa population.

Rhodes's Franchise and Ballot Act (1892) finally succeeded in raising the franchise qualification from £25 to £75, disenfranchising the poorest classes of all race groups (including poor whites) but effecting a disproportionately large percentage of the African voters. It also added literacy as a franchise qualification, intended to target the (still mostly illiterate) Xhosa voters of the Cape.

Finally, the Glen Grey Act (1894) re-drew the laws on rural African land tenure and effectively disqualified nearly all rural Africans from the vote.

The result was that, by the end of Rhodes's Ministry, only a small portion of relatively wealthy, educated, urban Black Africans were still permitted to vote.

Decades later, with the rise of Apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

after Union, all restrictions were removed for White voters, meaning that the remaining qualifications of the Cape Qualified Franchise only applied to non-whites.

Move towards Union

In the early twentieth century, following the tumults of the

In the early twentieth century, following the tumults of the Second Anglo-Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

, the whole of southern Africa was finally under the control of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

. The union of the various component states of the region was again discussed. Several previous attempts at union had failed, but in 1909 a National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year Nation ...

was instituted in Cape Town, to unite the Cape of Good Hope with Natal, the Transvaal, and the Orange Free State, to form a united country of "South Africa".

The Convention met in the Cape Assembly's chamber of the Cape Parliament building, and it was here that the new constitution for South Africa was drawn up.

The Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tr ...

was proclaimed the following year, in 1910, and the old Cape Parliamentary building became the home of the new Parliament of South Africa

The Parliament of the Republic of South Africa is South Africa's legislature; under the present Constitution of South Africa, the bicameral Parliament comprises a National Assembly and a National Council of Provinces. The current twenty-seve ...

. The provincial government of the Cape, now the "Cape Province", was set up in a new building nearby, the Pronvisiale-gebou.

Parliaments & Ministries of the Cape of Good Hope

Inaugural Parliament (1854)

* Western Province: ** Howson Edward Rutherfoord **Francis William Reitz, Sr.

Francis William Reitz Sr. MLC MLA (31 December 1810 - 26 June 1881) was an influential member of both houses of the Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope.

Early life and farming

Generally known simply as "Frank Reitz", he was born at his family's h ...

** Joseph Barry

** Johan Hendrik Wicht

** John Bardwell Ebden

** Dirk Gysbert van Breda

** Johannes de Wet LLD

** Henry Thomas Vigne

* Eastern Province:

** Andries Stockenström

Sir Andries Stockenström, 1st Baronet, (6 July 1792 in Cape Town – 16 March 1864 in London) was lieutenant governor of British Kaffraria from 13 September 1836 to 9 August 1838.

His efforts in restraining colonists from moving into Xhosa ...

** Robert Godlonton

** George Wood

** Henry Blaine

** Willem Simon Gregorius Metelerkamp

** William Fleming

** Gideon Daniel Joubert

* Western Province Districts:

** Hercules Crosse Jarvis, Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

** Saul Solomon, Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

** James Abercrombie MD, Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

** Francois Louis Charl Biccard MD, Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

** James Mortimer Maynard, Cape Division (southern Cape Peninsula)

** Thomas Watson, Cape Division

** Petrus Jacobus Bosman, Stellenbosch

** Christoffel Brand

Sir Christoffel Joseph Brand (21 June 1797 Cape Town – 19 May 1875 Cape Town) was a Cape jurist, politician, statesman and first Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of the Cape Colony.

Early life and education

Christoffel Brand was born ...

LLD, Stellenbosch

** Pieter Frederik Ryk de Villiers, Paarl

** Johan Georg Steytler, Paarl

** Frederick Duckitt, Malmesbury

** Hugo Hendrick Loedolff, Malmesbury

** Bryan Henry Darnell, Caledon

** Charles Aiken Fairbridge, Caledon

** Augustus Joseph Tancred DD, Clanwilliam

** Johannes Hendricus Brand LLD, Clanwilliam

** Egidius Benedictus Watermeyer LLD, Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

** John Percival Wiggins, Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

** John Molteno

Sir John Charles Molteno (5 June 1814 – 1 September 1886) was a soldier, businessman, champion of responsible government and the first Prime Minister of the Cape Colony.

Early life

Born in London into a large Anglo-Italian family, Molten ...

, Beaufort Beaufort may refer to:

People and titles

* Beaufort (surname)

* House of Beaufort, English nobility

* Duke of Beaufort (England), a title in the peerage of England

* Duke of Beaufort (France), a title in the French nobility

Places Polar regions

* ...

** James Christie, Beaufort Beaufort may refer to:

People and titles

* Beaufort (surname)

* House of Beaufort, English nobility

* Duke of Beaufort (England), a title in the peerage of England

* Duke of Beaufort (France), a title in the French nobility

Places Polar regions

* ...

** John Fairbairn, Swellendam

** John Barry, Swellendam

** Henry William Laws, George

** Frans Adriaan Swemmer, George

* Eastern Province Districts:

** James Thackwray, Grahamstown

Makhanda, also known as Grahamstown, is a town of about 140,000 people in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is situated about northeast of Port Elizabeth and southwest of East London. Makhanda is the largest town in the Makana ...

** Charles Pote, Grahamstown

Makhanda, also known as Grahamstown, is a town of about 140,000 people in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is situated about northeast of Port Elizabeth and southwest of East London. Makhanda is the largest town in the Makana ...

** Thomas Holden Bowker, Albany

** William Cock, Albany

** Johannes Christoffel Krog, Uitenhage

Uitenhage ( ; ), officially renamed Kariega, is a South African town in the Eastern Cape Province. It is well known for the Volkswagen factory located there, which is the biggest car factory on the African continent. Along with the city of Port E ...

** Stephanus Johannes Hartman, Uitenhage

Uitenhage ( ; ), officially renamed Kariega, is a South African town in the Eastern Cape Province. It is well known for the Volkswagen factory located there, which is the biggest car factory on the African continent. Along with the city of Port E ...

** John Paterson, Port Elizabeth

Gqeberha (), formerly Port Elizabeth and colloquially often referred to as P.E., is a major seaport and the most populous city in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is the seat of the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality, So ...

** Henry Fancourt White

Henry Fancourt White (25 May 1811 – 6 October 1866) was a British-born South African colonial assistant surveyor who played a part in construction of the Montagu Pass between George and Oudtshoorn, over the Outeniqua Mountains.

South Afri ...

, Port Elizabeth

Gqeberha (), formerly Port Elizabeth and colloquially often referred to as P.E., is a major seaport and the most populous city in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is the seat of the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality, So ...

** Robert Mitford Bowker, Somerset East

** Ralph Henry Arderne, Somerset East

** Jeremias Frederik Ziervogel , Graaff-Reinet

** Thomas Nicolaas German Muller, Graaff-Reinet

** Charles Lennox Stretch, Fort Beaufort

** Richard Joseph Painter, Fort Beaufort

** John George Franklin, Victoria East

** James Stewart, Victoria East

** Johannes Petrus Vorster, Albert

** Jacobus Johannes Meintjes, Albert

** James Collett, Cradock

** William Thornhill Gilfillan, Cradock

** Johan Georg Sieberhagen, Colesberg

** Ludwig Johan Frederik von Maltitz, Colesberg

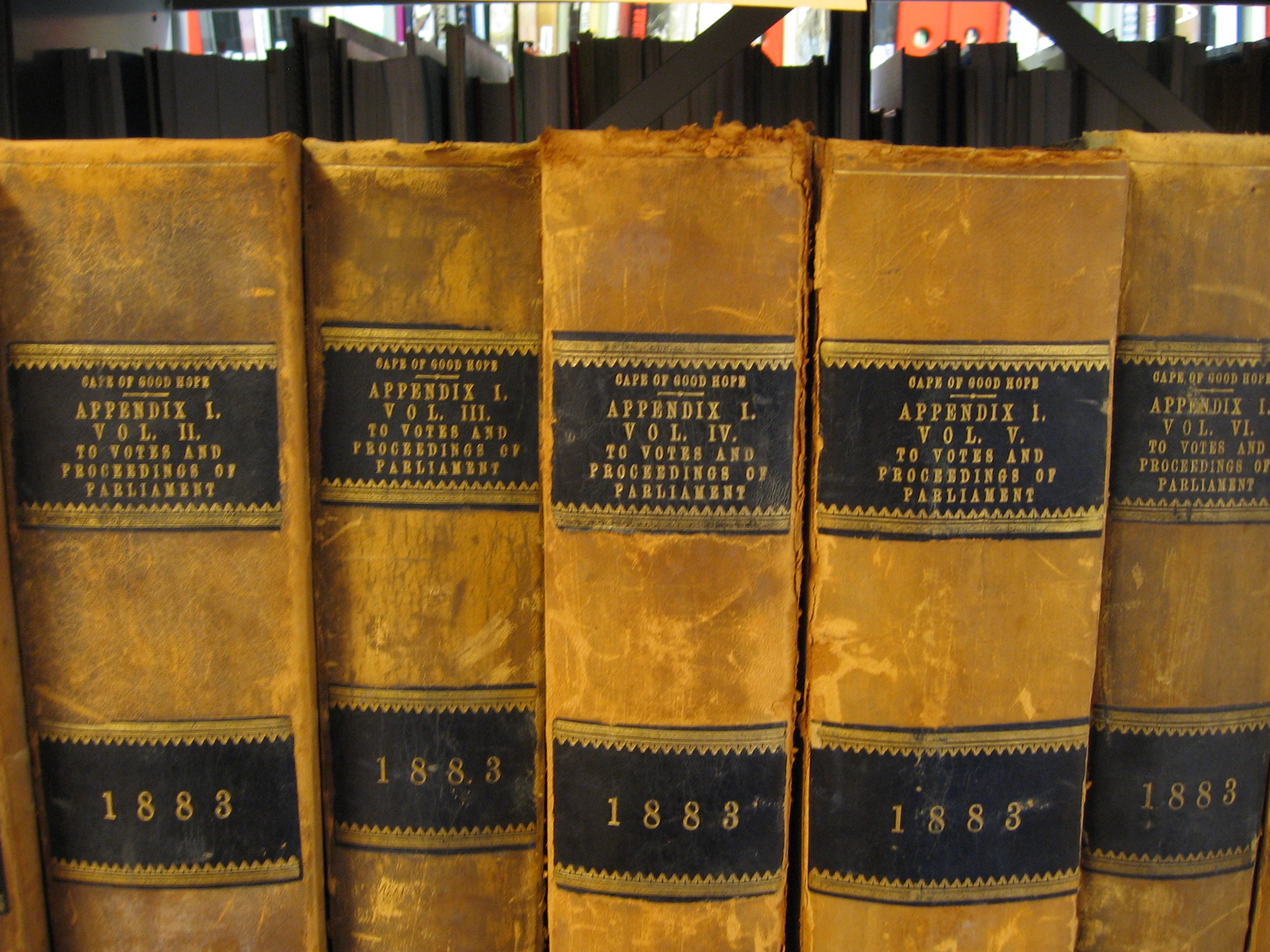

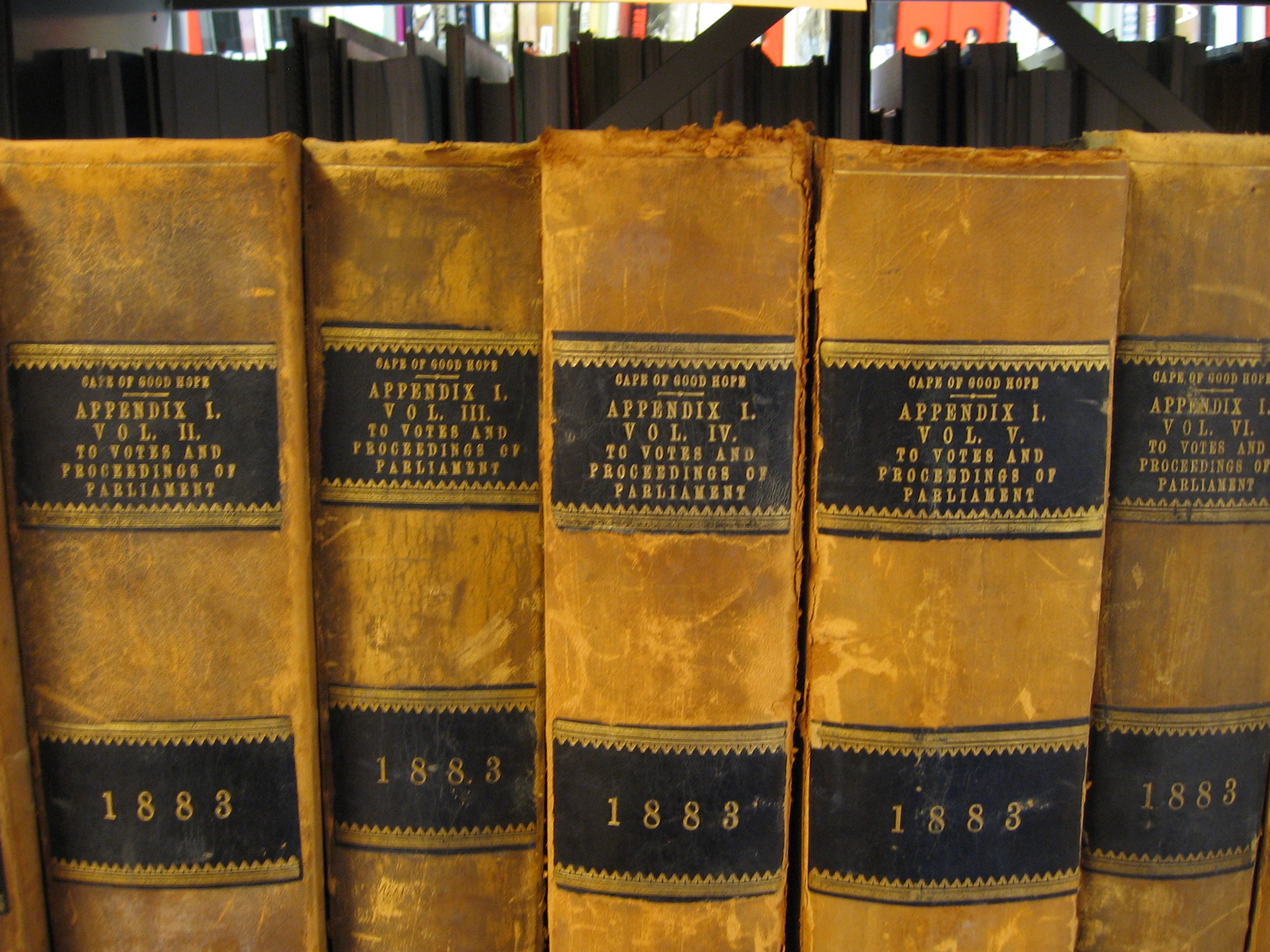

Parliaments of the Cape (1854–1910)

* 1st Cape Parliament (1854–1858) * 2nd Cape Parliament (1859–1863) * 3rd Cape Parliament (1864–1869) – ended by dissolution by the Cape Colony Governor * 4th Cape Parliament (1870–1873) * 5th Cape Parliament (1874–1878) * 6th Cape Parliament (1879–1883) * 7th Cape Parliament (1884–1888) * 8th Cape Parliament (1889–1893) * 9th Cape Parliament (1894–1898) – ended by unsuccessful appeal to country by Prime Minister Sprigg * 10th Cape Parliament (1898–1903) – ended by unsuccessful appeal to country by Prime Minister Sprigg * 11th Cape Parliament (1904–1907) – ended by unsuccessful appeal to country by Prime Minister Jameson * 12th Cape Parliament (1908–1910) – ended by the act of Union (31 May 1910)Speakers of the Cape Parliament (1854–1910)

*SirChristoffel Brand

Sir Christoffel Joseph Brand (21 June 1797 Cape Town – 19 May 1875 Cape Town) was a Cape jurist, politician, statesman and first Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of the Cape Colony.

Early life and education

Christoffel Brand was born ...

(1854–1873)

* Sir David Tennant (1874–1895)

* Sir Henry Juta (1896–1898)

* Sir Bisset Berry (1899–1907)

* Sir James Molteno (1908–1910)

Ministries of the Cape of Good Hope (1872–1910)

The parliament's executive governments ("Ministries") dated only from 1872, when the Cape first attained

The parliament's executive governments ("Ministries") dated only from 1872, when the Cape first attained responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

. Prior to that parliament worked under a Governor, who was appointed by the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of c ...

in London.

The post of prime minister of the Cape Colony also became extinct on 31 May 1910, when it joined the Union of South Africa.

Political parties

Early informal groupings (1854-1881)

For much of the Cape's history, the parliament operated without formal political parties. Instead, parliamentarians aligned temporarily – according to specific issues. Nonetheless, informal alliances began to form according to the constituencies' overall attitude to long-standing issues, such as

For much of the Cape's history, the parliament operated without formal political parties. Instead, parliamentarians aligned temporarily – according to specific issues. Nonetheless, informal alliances began to form according to the constituencies' overall attitude to long-standing issues, such as Responsible Government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

, the multi-racial franchise, territorial expansion, separatism and relations with the British government.

In the 1860s and early 70s, an alliance of parliamentarians came together in support of "

In the 1860s and early 70s, an alliance of parliamentarians came together in support of "Responsible Government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

". These parliamentarians were general opposed to continued imperial control, desired greater local independence; sought a greater focus on internal development rather than expanding the colony's boundaries; and professed a strong commitment to racial and regional unity throughout the Cape. Prominent leaders were William Porter, Saul Solomon, John Molteno, Hercules Jarvis and Charles Lennox Stretch. This alliance later became known as the "Westerners" due to their headquarters in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, or by the nickname of the "responsibles". Opposing them were a group of parliamentarians representing mainly white settler

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established a permanent residence there, often to colonize the area.

A settler who migrates to an area previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited may be described as a pioneer.

Settle ...

constituencies in the Eastern Cape near the frontier. Close to the neighbouring Xhosa lands, these politicians represented their constituents' fears of the more numerous Xhosa. They tended to support the continued status of the Cape as a colony, stronger policies regarding border defence and increased expansion into the north to open up lands for white settlement. They resented the political dominance of the more "liberal" Westerners and saw the solution to be a separate white "Eastern Cape Colony" under direct imperial control, with Port Elizabeth

Gqeberha (), formerly Port Elizabeth and colloquially often referred to as P.E., is a major seaport and the most populous city in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is the seat of the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality, So ...

as its capital. For much of this time they were led by the representative of Port Elizabeth, John Paterson. They were known as the "Easterners" or the "Separatist League".

This decades long struggle was brought to an end in 1872, with the apparent triumph of the liberal faction and the achievement of responsible government.

The newly elected Molteno government then brought together a broad alliance, run on liberal principles but incorporating several easterners and support from the Cape's Afrikaner and Black communities. The new government's inclusive policies extinguished the separatist league, but the ideology and interests of the frontier settlers survived and resurfaced years later. In the Cape Times 1876-1910 history, the 1870s was referred to as last decade before the onset of formal party divisions: "But in the 1870s, there were still no clearly defined political parties in the Cape Parliament. Responsible government had been granted in 1872 and the first Prime Minister, J.C. Molteno, was still in office. Saul Solomon, in spite of his diminutive size and physical handicap, was at the height of his powers and was probably the outstanding figure in the House, noted for his outspoken liberalism and his concern for the interests of Africans."G.Shaw: ''Some Beginnings: The Cape Times 1876-1910''. London: Oxford University Press. 1975. . p.xiii.

Rise of political parties (1881-1910)

Two key events contributed to the rise of political parties. The first was the 1878 annexation of the Transvaal and the ensuing

Two key events contributed to the rise of political parties. The first was the 1878 annexation of the Transvaal and the ensuing First Anglo-Boer War

The First Boer War ( af, Eerste Vryheidsoorlog, literally "First Freedom War"), 1880–1881, also known as the First Anglo–Boer War, the Transvaal War or the Transvaal Rebellion, was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881 betwee ...

. After dismissing the Transvaal government, the Cape Colony Governor installed a former separatist, John Gordon Sprigg

Sir John Gordon Sprigg, (27 April 1830 – 4 February 1913) was an English-born colonial administrator, politician and four-time prime minister of the Cape Colony.

Early life

Sprigg was born in Ipswich, England, into a strongly Puritan fa ...

, as the new Prime Minister, with instructions to implement the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of c ...

's policies. Sprigg formed a cabinet composed entirely of Eastern frontier white settlers, but contributed to a new pro-imperialist ideology that was not tied to any particular region of the Cape, or indeed, of southern Africa. The attempted annexations of the Boer republics and perceptions of exclusion in the Cape Colony caused growing resentment in the Afrikaner or "Cape Dutch

Cape Dutch, also commonly known as Cape Afrikaners, were a historic socioeconomic class of Afrikaners who lived in the Western Cape during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The terms have been evoked to describe an affluent, apolitical ...

" population.

This led to the second key event, which was the founding of the Afrikaner Bond in 1881. The Afrikaner Bond was the Cape's first formal political party, headed by Jan Hendrik Hofmeyr (Onze Jan), and taking a strong stance for Afrikaner rights and (increasingly) against the political empowerment of the Cape's black citizens. The formation of the Bond severely weakened the liberal "Westerners" by splitting this bloc, and beginning their decline. The resulting three parties aligned differently according to the predominant issues of the day, with the Afrikaner Bond playing a central role as "King-maker": The liberals and the Bond agreed on the need to minimise imperial intervention in southern Africa, while the pro-imperialists and the Bond agreed on further restricting the rights of the Cape's black citizens.

The pro-imperialist grouping was by now known as "Progressives

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, techn ...

", and this movement reached the height of its power under Prime Minister Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902) was a British mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his Bri ...

. Rhodes's orchestration of the Jameson Raid sharply polarised the Cape's politics to an unprecedented degree.

The remaining liberal "westerners" formed the " South African Party" but were too weak to oppose Rhodes's Progressives alone, and so allied with the Afrikaner Bond to fight Rhodes's dominance. This controversial alliance with the racist Bond caused many of the South African Party's black voters to abandon it. It came to power briefly under its liberal leader William Schreiner but overall the ensuing decades were dominated by the Progressive Party.

In 1908, John X Merriman finally led the South African Party to electoral victory, a mere two years before the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910.

The remaining liberal "westerners" formed the " South African Party" but were too weak to oppose Rhodes's Progressives alone, and so allied with the Afrikaner Bond to fight Rhodes's dominance. This controversial alliance with the racist Bond caused many of the South African Party's black voters to abandon it. It came to power briefly under its liberal leader William Schreiner but overall the ensuing decades were dominated by the Progressive Party.

In 1908, John X Merriman finally led the South African Party to electoral victory, a mere two years before the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910.

Political parties after Union (1910)

After Union, the South African Party merged with the Afrikaner Bond, Het Volk of the Transvaal and Orangia Unie of the Orange Free State, to form a new Union-wide South African Party. After this merger, the policies of the larger Afrikaner parties came to predominate and the distinctive liberalness of the original South African Party was subsumed, as South Africa began its long slide into Apartheid. Meanwhile, the Progressives (renamed the "Union Party of the Cape") merged with the Progressive Association of the Transvaal and the Constitutional Party of the Orange Free State to form the Unionist Party. The Democratic Alliance traces its origins to these parties through numerous successors.See also

* Afrikaner Bond * Progressive Party (Cape Colony) * South African Party (Cape Colony) * List of prime ministers of the Cape of Good HopeReferences

{{reflist 1854 establishments in the Cape Colony 1910 disestablishments in South Africa Defunct bicameral legislatures Government of South AfricaCape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with ...

Politics of the Cape Colony

South African parliaments