Paolo Sarpi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

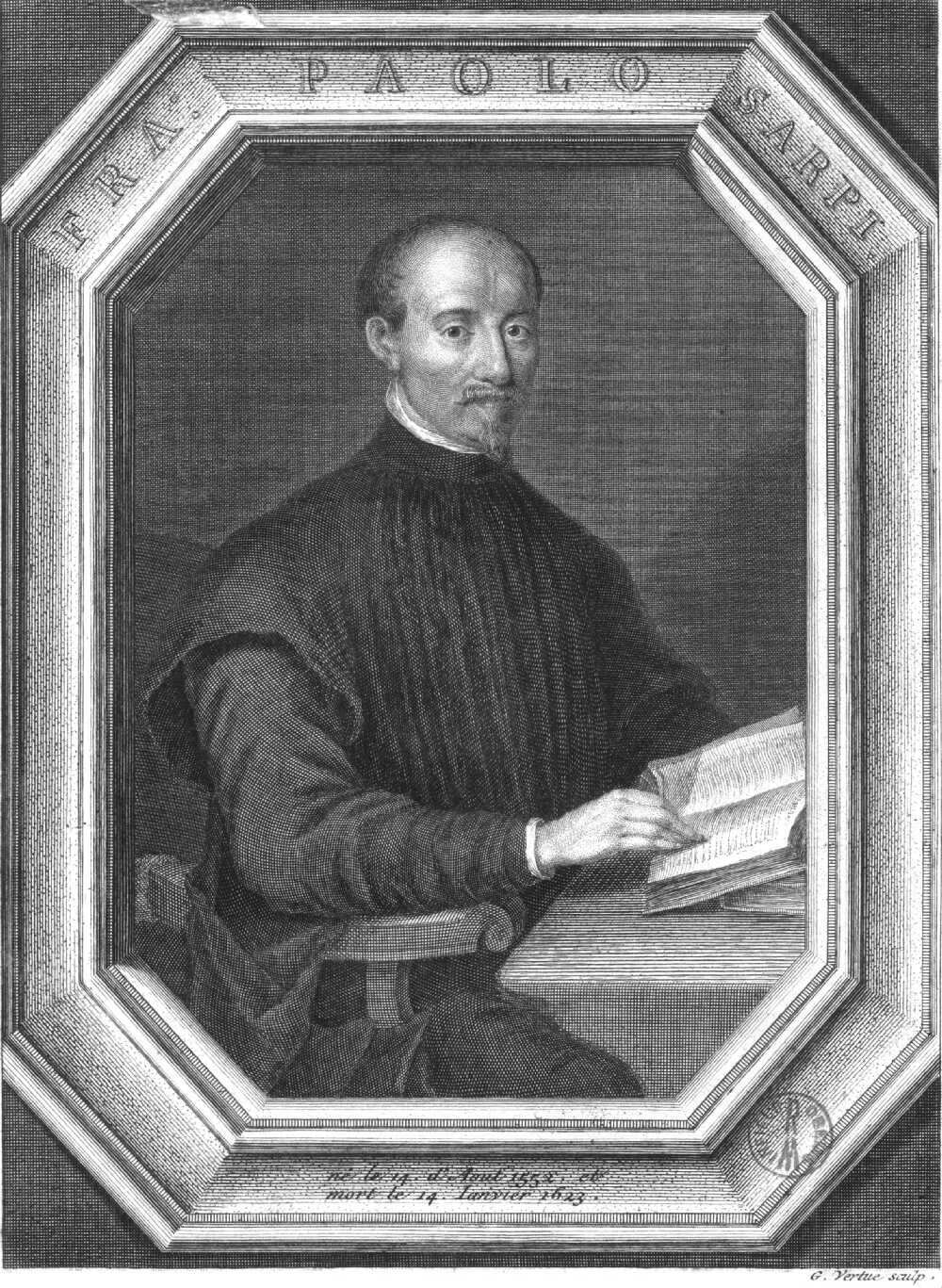

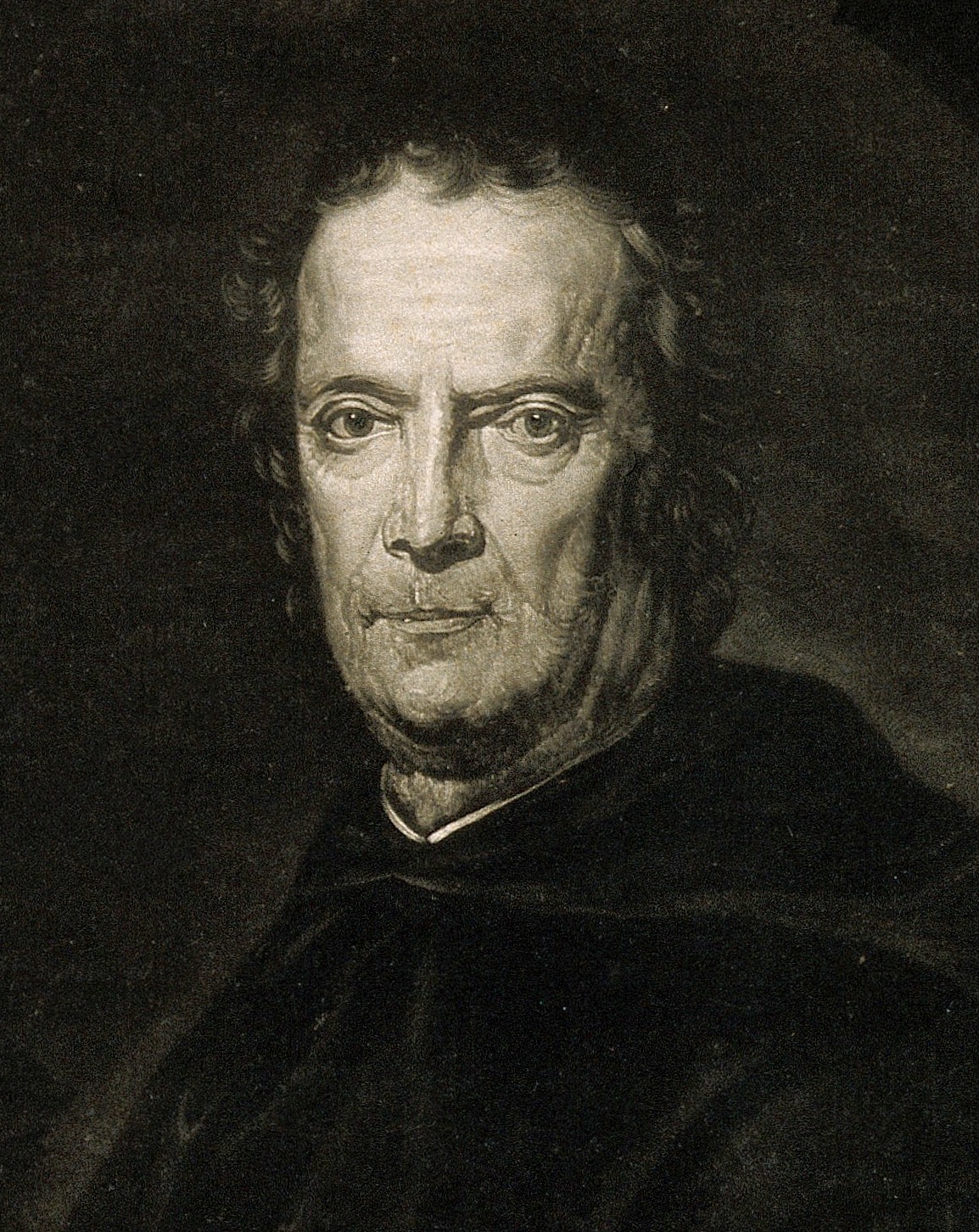

Paolo Sarpi (14 August 1552 – 15 January 1623) was a

Paolo Sarpi (14 August 1552 – 15 January 1623) was a

The republic rewarded Sarpi with the distinction of State Counsellor in Jurisprudence and the liberty of access to the state archives. These honours exasperated his adversaries, particularly Pope Paul V. In September 1607, at the instigation of the pope and his Cardinal nephew Scipio Borghese, Fra Sarpi became the target of an assassination attempt. A defrocked friar and brigand by the name of Rotilio Orlandini, assisted by his two brothers-in-law, agreed to kill Sarpi for the sum of 8,000 crowns. However, Orlandini's plot was discovered, and when the three assassins crossed from Papal into Venetian territory they were arrested and imprisoned.Robertson, Alexander (1893) ''Fra Paolo Sarpi: the Greatest of the Venetians'', London: Sampson, Low, Marston & Co. pp. 114–17

On 5 October 1607, Sarpi was attacked by assassins and left for dead with three stiletto thrusts, but he recovered. His attackers found both refuge and a welcome reception in the papal territories (described by a contemporary as a "triumphal march"), and papal enthusiasm for the assassins cooled only after learning that Brother Sarpi was not dead after all. The leader of the assassins, Poma, declared that he had attempted the murder for religious reasons. Sarpi himself, when his surgeon commented on the ragged and inartistic character of the wounds, responded, "''Agnosco stylum Romanae Curiae''" ("I recognize the style of the Roman Curia"). Sarpi's would-be assassins settled in Rome, and were eventually granted a pension by the viceroy of Naples,

The republic rewarded Sarpi with the distinction of State Counsellor in Jurisprudence and the liberty of access to the state archives. These honours exasperated his adversaries, particularly Pope Paul V. In September 1607, at the instigation of the pope and his Cardinal nephew Scipio Borghese, Fra Sarpi became the target of an assassination attempt. A defrocked friar and brigand by the name of Rotilio Orlandini, assisted by his two brothers-in-law, agreed to kill Sarpi for the sum of 8,000 crowns. However, Orlandini's plot was discovered, and when the three assassins crossed from Papal into Venetian territory they were arrested and imprisoned.Robertson, Alexander (1893) ''Fra Paolo Sarpi: the Greatest of the Venetians'', London: Sampson, Low, Marston & Co. pp. 114–17

On 5 October 1607, Sarpi was attacked by assassins and left for dead with three stiletto thrusts, but he recovered. His attackers found both refuge and a welcome reception in the papal territories (described by a contemporary as a "triumphal march"), and papal enthusiasm for the assassins cooled only after learning that Brother Sarpi was not dead after all. The leader of the assassins, Poma, declared that he had attempted the murder for religious reasons. Sarpi himself, when his surgeon commented on the ragged and inartistic character of the wounds, responded, "''Agnosco stylum Romanae Curiae''" ("I recognize the style of the Roman Curia"). Sarpi's would-be assassins settled in Rome, and were eventually granted a pension by the viceroy of Naples,

The remainder of Sarpi's life was spent peacefully in his

The remainder of Sarpi's life was spent peacefully in his

In 1619 his chief literary work, ''Istoria del Concilio Tridentino'' (History of the

In 1619 his chief literary work, ''Istoria del Concilio Tridentino'' (History of the

Johnson, Samuel (1810). "Father Paul Sarpi," pp. 3–10 in ''The Works of Samuel Johnson, L.L.D., in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 10''. London: Jay Nichols and Son.

Bouwsma, William J. "Venice, Spain, and the Papacy: Paolo Sarpi and the Renaissance Tradition"

from William J. Bouwsma's ''A Usable Past: Essays in European Cultural History.'' Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sarpi, Paolo 1552 births 1623 deaths Servites Italian humanists 17th-century Italian historians Republic of Venice scientists Italian male writers 16th-century Venetian writers 16th-century male writers 17th-century Venetian writers Canon law jurists

Paolo Sarpi (14 August 1552 – 15 January 1623) was a

Paolo Sarpi (14 August 1552 – 15 January 1623) was a Venetian

Venetian often means from or related to:

* Venice, a city in Italy

* Veneto, a region of Italy

* Republic of Venice (697–1797), a historical nation in that area

Venetian and the like may also refer to:

* Venetian language, a Romance language s ...

historian, prelate, scientist, canon lawyer

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is t ...

, and statesman active on behalf of the Venetian Republic

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

during the period of its successful defiance of the papal interdict

In Catholic canon law, an interdict () is an ecclesiastical censure, or ban that prohibits persons, certain active Church individuals or groups from participating in certain rites, or that the rites and services of the church are banished from h ...

(1605–1607) and its war (1615–1617) with Austria over the Uskok

The Uskoks ( hr, Uskoci, , singular: ; notes on naming) were irregular soldiers in Habsburg Croatia that inhabited areas on the eastern Adriatic coast and surrounding territories during the Ottoman wars in Europe. Bands of Uskoks fought a g ...

pirates. His writings, frankly polemical and highly critical of the Catholic Church and its Scholastic tradition, "inspired both Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

and Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English historian, writer, and member of parliament. His most important work, '' The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788, i ...

in their own historical debunkings of priestcraft." Sarpi's major work, the ''History of the Council of Trent'' (1619), was published in London in 1619; other works: a ''History of Ecclesiastical Benefices'', ''History of the Interdict'' and his ''Supplement to the History of the Uskoks'', appeared posthumously. Organized around single topics, they are early examples of the genre of the historical monograph

A monograph is a specialist work of writing (in contrast to reference works) or exhibition on a single subject or an aspect of a subject, often by a single author or artist, and usually on a scholarly subject.

In library cataloging, ''monogra ...

.

As a defender of the liberties of Republican Venice and proponent of the separation of Church and state, Sarpi attained fame as a hero of republicanism and free thought and possible crypto Protestant. His last words

Last words are the final utterances before death. The meaning is sometimes expanded to somewhat earlier utterances.

Last words of famous or infamous people are sometimes recorded (although not always accurately) which became a historical and liter ...

, " Esto perpetua" ("may she .e., the republiclive forever"), were recalled by John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

in 1820 in a letter to Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, when Adams "wished 'as devoutly as Father Paul for the preservation of our vast American empire and our free institutions', as Sarpi had wished for the preservation of Venice and its institutions."

Sarpi was also an experimental scientist, a proponent of the Copernican system, a friend and patron of Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He ...

, and a keen follower of the latest research on anatomy, astronomy, and ballistics at the University of Padua

The University of Padua ( it, Università degli Studi di Padova, UNIPD) is an Italian university located in the city of Padua, region of Veneto, northern Italy. The University of Padua was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from ...

. His extensive network of correspondents included Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

and William Harvey.

Sarpi believed that government institutions should rescind their censorship of the Avvisi—the newsletters that started to be common in his time—and instead of censorship, publish their own versions of the news to counter enemy publications. In that spirit, Sarpi himself published several pamphlets in defense of Venice's rights over the Adriatic. As such, Sarpi could be considered as an early advocate of the freedom of the press, though the concept did not yet exist in his lifetime.

Early years

He was born Pietro Sarpi inVenice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

. His father was a merchant, although not a successful one, his mother a Venetian noblewoman. His father died while he was still a child. The brilliant and precocious boy was educated by his maternal uncle, a school teacher, and then by Giammaria Capella, a monk in the Augustinian Servite order. In 1566, at the age of thirteen, he entered the Servite order, assuming the name of Fra (Brother) Paolo, by which, with the epithet Servita, he was always known to his contemporaries.

Sarpi was assigned to a monastery in Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and '' comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture. In 2017, it was named as the Eur ...

around 1567. In 1570 he sustained theses at a disputation there, and was invited to remain as court theologian to Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga. Sarpi remained four years at Mantua, studying mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

and oriental languages. He then went to Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

in 1575, where he was an adviser to Charles Borromeo, the saint and bishop but was transferred by his superiors to Venice, as professor of philosophy at the Servite convent. In 1579, he became Provincial of the Venetian Province of the Servite order, while studying at the University of Padua. At the age of twenty-seven he was appointed Procurator General for the order. In this capacity he was sent to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, where he interacted with three successive popes, the grand inquisitor, and other influential people.

Sarpi returned to Venice in 1588 and passed the next 17 years in study, occasionally interrupted by the internal disputes of his community. In 1601, he was recommended by the Venetian senate for the bishopric of Caorle, but the papal nuncio

An apostolic nuncio ( la, nuntius apostolicus; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international ...

, who wished to obtain it for a ''protégé'' of his own, accused Sarpi of having denied the immortality of the soul and controverted the authority of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

. An attempt to obtain another bishopric in the following year also failed, Pope Clement VIII

Pope Clement VIII ( la, Clemens VIII; it, Clemente VIII; 24 February 1536 – 3 March 1605), born Ippolito Aldobrandini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 February 1592 to his death in March 1605.

Born ...

having taken offense at Sarpi's habit of corresponding with learned heretics.

Venice in conflict with the Pope

Clement VIII died in March 1605, and the attitude of his successor Pope Paul V strained the limits of papal prerogative. Venice simultaneously adopted measures to restrict it: the right of the secular tribunals to take cognizance of the offences of ecclesiastics had been asserted in two leading cases and the scope of two ancient laws of the city, that were: one forbidding the foundation of new churches or ecclesiastical congregations without the consent of the state, the other forbidding acquisition of property by priests or religious bodies. These laws had been extended over the entire territory of the republic. In January 1606, the papal nuncio delivered a brief demanding the unconditional submission of the Venetians. The senate promised protection to all ecclesiastics who should in this emergency aid the republic by their counsel. Sarpi presented a memoir, pointing out that the threatened censures might be met in two ways – ''de facto'', by prohibiting their publication, and ''de jure'', by an appeal to a general council. The document was well received, and Sarpi was made canonist and theological counsellor to the republic. The following April, hopes of compromise were dispelled by Paul'sexcommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

of the Venetians and his attempt to lay their dominions under an interdict. Sarpi entered energetically into the controversy. It was unprecedented for an ecclesiastic of his eminence to argue the subjection of the clergy to the state. He began by republishing the anti-papal opinions of the canonist Jean Gerson (1363–1429). In an anonymous tract published shortly afterwards (''Risposta di un Dottore in Teologia''), he laid down principles which struck radically at papal authority in secular matters. This book was promptly included in the ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum

The ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' ("List of Prohibited Books") was a list of publications deemed heretical or contrary to morality by the Sacred Congregation of the Index (a former Dicastery of the Roman Curia), and Catholics were forbid ...

'', and Cardinal Bellarmine

Robert Bellarmine, SJ ( it, Roberto Francesco Romolo Bellarmino; 4 October 1542 – 17 September 1621) was an Italian Jesuit and a cardinal of the Catholic Church. He was canonized a saint in 1930 and named Doctor of the Church, one of only 3 ...

attacked Gerson's work with severity. Sarpi then replied in an ''Apologia''. The ''Considerazioni sulle censure'' and the ''Trattato dell' interdetto'', the latter partly prepared under his direction by other theologians, soon followed. Numerous other pamphlets appeared, inspired or controlled by Sarpi, who had received the further appointment of censor of everything written at Venice in defence of the republic.

Following Sarpi's advice, the Venetian clergy largely disregarded the interdict and discharged their functions as usual, the major exception being the Jesuits

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

, who left and were simultaneously expelled officially.Eric Cochrane (1988) ''Italy 1530–1630''. Longman. . p. 262. The Catholic powers France and Spain refused to be drawn into the quarrel and resorted to diplomacy. At length (April 1607), the mediation of King Henry IV of France

Henry IV (french: Henri IV; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry or Henry the Great, was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 1610. He was the first monar ...

arranged a compromise which salvaged the pope's dignity but conceded the points at issue. The two priests were returned to Rome but with Venice reserving the right to try clergy in civil courts. The outcome proved not so much the defeat of papal pretensions as the recognition that interdicts and excommunication had lost their force. "The Republic,” said Sarpi, “has given a shake to papal claims. For whoever heard till now of a papal interdict, published with all solemnity, ending in smoke?”

Assassination attempt

The republic rewarded Sarpi with the distinction of State Counsellor in Jurisprudence and the liberty of access to the state archives. These honours exasperated his adversaries, particularly Pope Paul V. In September 1607, at the instigation of the pope and his Cardinal nephew Scipio Borghese, Fra Sarpi became the target of an assassination attempt. A defrocked friar and brigand by the name of Rotilio Orlandini, assisted by his two brothers-in-law, agreed to kill Sarpi for the sum of 8,000 crowns. However, Orlandini's plot was discovered, and when the three assassins crossed from Papal into Venetian territory they were arrested and imprisoned.Robertson, Alexander (1893) ''Fra Paolo Sarpi: the Greatest of the Venetians'', London: Sampson, Low, Marston & Co. pp. 114–17

On 5 October 1607, Sarpi was attacked by assassins and left for dead with three stiletto thrusts, but he recovered. His attackers found both refuge and a welcome reception in the papal territories (described by a contemporary as a "triumphal march"), and papal enthusiasm for the assassins cooled only after learning that Brother Sarpi was not dead after all. The leader of the assassins, Poma, declared that he had attempted the murder for religious reasons. Sarpi himself, when his surgeon commented on the ragged and inartistic character of the wounds, responded, "''Agnosco stylum Romanae Curiae''" ("I recognize the style of the Roman Curia"). Sarpi's would-be assassins settled in Rome, and were eventually granted a pension by the viceroy of Naples,

The republic rewarded Sarpi with the distinction of State Counsellor in Jurisprudence and the liberty of access to the state archives. These honours exasperated his adversaries, particularly Pope Paul V. In September 1607, at the instigation of the pope and his Cardinal nephew Scipio Borghese, Fra Sarpi became the target of an assassination attempt. A defrocked friar and brigand by the name of Rotilio Orlandini, assisted by his two brothers-in-law, agreed to kill Sarpi for the sum of 8,000 crowns. However, Orlandini's plot was discovered, and when the three assassins crossed from Papal into Venetian territory they were arrested and imprisoned.Robertson, Alexander (1893) ''Fra Paolo Sarpi: the Greatest of the Venetians'', London: Sampson, Low, Marston & Co. pp. 114–17

On 5 October 1607, Sarpi was attacked by assassins and left for dead with three stiletto thrusts, but he recovered. His attackers found both refuge and a welcome reception in the papal territories (described by a contemporary as a "triumphal march"), and papal enthusiasm for the assassins cooled only after learning that Brother Sarpi was not dead after all. The leader of the assassins, Poma, declared that he had attempted the murder for religious reasons. Sarpi himself, when his surgeon commented on the ragged and inartistic character of the wounds, responded, "''Agnosco stylum Romanae Curiae''" ("I recognize the style of the Roman Curia"). Sarpi's would-be assassins settled in Rome, and were eventually granted a pension by the viceroy of Naples, Pedro Téllez-Girón, 3rd Duke of Osuna

Pedro Téllez-Girón, 3rd Duke of Osuna (17 February 1574 – 20 September 1624) was a Spanish nobleman and politician. He was the 2nd Marquis of Peñafiel, 7th Count of Ureña, Spanish Viceroy of Sicily (1611–1616), Viceroy of Naples (1616– ...

.

Later life

The remainder of Sarpi's life was spent peacefully in his

The remainder of Sarpi's life was spent peacefully in his cloister

A cloister (from Latin ''claustrum'', "enclosure") is a covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle or garth. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church, commonly against ...

, though plots against him continued to be formed, and he occasionally spoke of taking refuge in England. When not engaged in preparing state papers, he devoted himself to scientific studies, and composed several works. He served the state to the last. The day before his death, he had dictated three replies to questions on affairs of the Venetian Republic, and his last words were " Esto perpetua," or "may she endure forever."

These words were adopted as the state motto of Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Monta ...

and appear on the back of the 2007 Idaho quarter, as well as being taken up by various other groups and bodies in different countries (see " Esto perpetua").

''History of the Council of Trent''

In 1619 his chief literary work, ''Istoria del Concilio Tridentino'' (History of the

In 1619 his chief literary work, ''Istoria del Concilio Tridentino'' (History of the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation, it has been described a ...

), was printed at London, published under the name of Pietro Soave Polano, an anagram of Paolo Sarpi Veneto (plus o). The editor, Marco Antonio de Dominis, did some work on polishing the text. He has been accused of falsifying it, but a comparison with a manuscript corrected by Sarpi himself shows that the alterations are unimportant. Translations into other languages followed: there were the English translation by Nathaniel Brent and a Latin edition in 1620 made by Adam Newton, de Dominis, and William Bedell, and French and German editions.

Its emphasis was on the role of the Papal Curia, and its slant on the Curia hostile. This was unofficial history, rather than a commission, and treated ecclesiastical history as politics. Sarpi in Mantua had known Camillo Olivo, secretary to Cardinal Ercole Gonzaga

Ercole Gonzaga (23 November 1505 – 2 March 1563) was an Italian Cardinal.

Biography

Born in Mantua, he was the son of the Marquis Francesco Gonzaga and Isabella d'Este, and nephew of Cardinal Sigismondo Gonzaga. He studied philosophy at Bolo ...

. His attitude, "bitterly realistic" for John Hale, was coupled with a criticism that the Tridentine settlement was not conciliatory but designed for further conflict. Denys Hay calls it "a kind of Anglican picture of the debates and decisions", and Sarpi was much read by Protestants; John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and politica ...

called him the "great unmasker".

Sarpi's work attained such fame that the Vatican opened its archives to Cardinal Francesco Sforza Pallavicino, whom it commissioned to write a three volume rebuttal, entitled the ''Istoria del Concilio di Trento, scritta dal P. Sforza Pallavicino, della Comp. di Giesù ove insieme rifiutasi con auterevoli testimonianze un Istoria falsa divolgata nello stesso argomento sotto nome di Petro Soave Polano'' ("The History of the Council of Trent written by P. Sforza Pallavicino, of the Company of Jesus, in which a false history upon the same argument put forth under the name of Petro Soave Polano is refuted by means of authoritative testimony", 1656–1657). The great nineteenth century historian Leopold von Ranke

Leopold von Ranke (; 21 December 1795 – 23 May 1886) was a German historian and a founder of modern source-based history. He was able to implement the seminar teaching method in his classroom and focused on archival research and the analysis ...

(''History of the Popes''), examined both Sarpi and Pallavicino's treatments of manuscript materials and judged them both as falling short of his own strict standards of objectivity. The former is described as moved by deadly hatred – malignant in his purpose and reckless in his means – fabricating falsehoods and distorting or perverting truths; while the Jesuit, though scrupulously correct in the documents he exhibits, often suppresses those opposed to his views. Nevertheless Ranke rated the quality of Sarpi's work very highly, considering him superior to Guicciardini. Sarpi never acknowledged his authorship, and baffled all the efforts of Louis II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé to extract the secret from him.

Hubert Jedin Hubert Jedin (17 June 1900, in Groß Briesen, Friedewalde, Silesia – 16 July 1980, in Bonn) was a Catholic Church historian from Germany, whose publications specialized on the history of ecumenical councils in general and the Council of Tre ...

's multi-volume history of the Council of Trent (1961), also Vatican authorized, likewise faults Sarpi's use of sources. David Wootton believes, however, that there is evidence Sarpi may have used original documents that have not survived and he calls Sarpi's treatment of Council quite careful despite its partisan framing.

Other works

In 1615, a dispute occurred between the Venetian government and theInquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

over the prohibition of a book. In 1613 the Senate had asked Sarpi to write about the history and procedure of the Venetian Inquisition. He argued that this had been set up in 1289, but as a Venetian state institution. The pope of the time, Nicholas IV, had merely consented to its creation. This work appeared in English translation by Robert Gentilis in 1639.

A Machiavellian tract on the fundamental maxims of Venetian policy (''Opinione come debba governarsi la repubblica di Venezia'') has been attributed to Sarpi and used by some of his posthumous adversaries to blacken his memory, but it in fact dates from 1681. He did not complete a reply which he had been ordered to prepare to the ''Squitinio della libertà veneta'' (1612, attributed to Alfonso de la Cueva

Alfonso de la Cueva-Benavides y Mendoza-Carrillo, marqués de Bedmar (first name also spelled ''Alonso'', often used was the title ''Bedmar'') (25 July 157410 August 1655) was a Spanish diplomat, bishop and Roman Catholic cardinal. He was born ...

), which he perhaps found unanswerable. In folio appeared his ''History of Ecclesiastical Benefices'', in which, said Matteo Ricci, "he purged the church of the defilement introduced by spurious decretals." It appeared in English translation in 1736 with a biography by John Lockman. In 1611, he attacked misuse of the right of asylum claimed for churches, in a work that was immediately placed on the Index.

His posthumous ''History of the Interdict'' was printed at Venice the year after his death, with the disguised imprint of Lyon. Sarpi's memoirs on state affairs remained in the Venetian archives. Consul Smith's collection of tracts in the Interdict controversy went to the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

. Francesco Griselini's ''Memorie e aneddote'' (1760) was based on Sarpi's unpublished writings, later destroyed by book burning.

Correspondence networks and published letters

Sarpi was the center of a vast political and scholarly network of eminent correspondents, from which about 430 of his letters have survived. Early letter collections were: "Lettere Italiane di Fra Sarpi" (Geneva, 1673); Scelte lettere inedite de P. Sarpi", edited by Aurelio Bianchi-Giovini (Capolago, 1833); "Lettere raccolte di Sarpi", edited by Polidori (Florence, 1863); "Lettere inedite di Sarpi a S. Contarini", edited by Castellani (Venice, 1892). Some hitherto unpublished letters of Sarpi were edited by Karl Benrath and published, under the title ''Paolo Sarpi. Neue Briefe'', 1608–1610 (at Leipzig in 1909). A modern edition (1961) ''Lettere ai Gallicani'' has been published of his hundreds of letters to French correspondents. These are mainly to jurists: Jacques Auguste de Thou, Jacques Lechassier, Jacques Gillot. Another correspondent was William Cavendish, 2nd Earl of Devonshire; English translations byThomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book '' Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

of 45 letters to the Earl were published (Hobbes acted as the Earl's secretary), and it is now thought that these are jointly from Sarpi (when alive) and his close friend Fulgenzio Micanzio Fulgenzio Micanzio (1570 in Passirano – 1654 in Venice) was a Lombardic Servite friar and theologian. A close associate of Paolo Sarpi, he undertook correspondence for Sarpi and became his biographer. He also was a supporter of Galileo Galil ...

, something concealed at the time as a matter of prudence. Micanzio was also in touch with Dudley Carleton, 1st Viscount Dorchester. Giusto Fontanini's ''Storia arcana della vita di Pietro Sarpi'' (1863), a bitter libel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defi ...

, is important for the letters of Sarpi it contains.

Views

Sarpi read and was influenced by the skepticism of Michel de Montaigne and his disciplePierre Charron

Pierre Charron (; 1541 – 16 November 1603, Paris), French Catholic theologian and major contributor to the new thought of the 17th century. He is remembered for his controversial form of skepticism and his separation of ethics from religion as ...

. As an historian and thinker in the realist tradition of Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

, Machiavelli, and Guicciardini, he stressed that patriotism as national pride or honor could play a central role in social control. At various times during his lifetime he was suspected of a lack of orthodoxy in religion: he appeared before the Inquisition around 1575, in 1594, and in 1607.

Sarpi hoped for toleration of Protestant worship in Venice and the establishment of a Venetian free church by which the decrees of the council of Trent would have been rejected. Sarpi discusses his intimate beliefs and motives in his correspondence with Christoph von Dohna, envoy to Venice for Christian I, Prince of Anhalt-Bernburg. Sarpi told Dohna that he greatly disliked saying Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different ele ...

and celebrated it as seldom as possible, but that he was compelled to do so, as he would otherwise seem to admit the validity of the papal prohibition. Sarpi's maxim was that "God does not regard externals so long as the mind and heart are right before Him." Another maxim Sarpi formulated to Dohna was ''Le falsità non dico mai mai, ma la verità non a ognuno'' ("I never, never tell falsehoods, but the truth I do not tell to everyone.").

Sarpi at the end of his life wrote to Daniel Heinsius that he favored the side of the Calvinist Contra-Remonstrants

Franciscus Gomarus (François Gomaer; 30 January 1563 – 11 January 1641) was a Dutch theologian, a strict Calvinist and an opponent of the teaching of Jacobus Arminius (and his followers), whose theological disputes were addressed at the Synod ...

at the Synod of Dort

The Synod of Dort (also known as the Synod of Dordt or the Synod of Dordrecht) was an international Synod held in Dordrecht in 1618–1619, by the Dutch Reformed Church, to settle a divisive controversy caused by the rise of Arminianism. The ...

. Yet although Sarpi corresponded with James I of England

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

and admired the English ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

'', Catholic theologian Le Courayer in the 18th century wrote that Sarpi was no Protestant, terming him ''"Catholique en gros et quelque fois Protestant en détail"'' ("Catholic in general and sometimes Protestant in detail"). In the twentieth century, William James Bouwsma found Sarpi to have been a philo-Protestant whose religious ideas were nevertheless "consistent with Catholic orthodoxy," and Eric Cochrane described him as deeply religious in the typical spirit of the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

. Corrado Vivanti saw Sarpi as a religious reformer who aspired toward an ecumenical church, and historian Diarmaid MacCulloch describes Sarpi as having moved away from dogmatic Christianity. On the other hand, in 1983 David Wootton made a case for Sarpi as a scientific materialist and thus as likely a "veiled" atheist who was "hostile to Christianity itself" and whose politics looked forward to a secular society

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on secular, naturalistic considerations.

Secularism is most commonly defined as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state, and may be broadened to a sim ...

unrealizable in his own time, a thesis that has won some acceptance. Jaska Kainulainen, on the other hand, asserts that the thesis that Sarpi was an atheist contradicts the historical record, observing that neither Sarpi's pronounced skepticism nor his pessimistic view of capabilities are incompatible with religious faith:

Sarpi’s writings do not support the claim that he was an atheist. In fact, from an atheistic point of view, systematic skepticism can be seen as providing support of religious belief, because atheists' position postulates certain knowledge of God's inexistence. ...In his case the fundamental question was not the existence of God, but whether knowledge of God was obtainable by reason or by faith. His response was unequivocal: he was convinced that knowledge of divine matters was attained sola fide and he explicitly claimed that in religious matters one could not make judgments based on reason, but instead, they had to be based on affection or feeling

Scientific scholar

Sarpi wrote notes on François Viète which established his proficiency inmathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

, and a metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

treatise now lost

Lost may refer to getting lost, or to:

Geography

* Lost, Aberdeenshire, a hamlet in Scotland

*Lake Okeechobee Scenic Trail, or LOST, a hiking and cycling trail in Florida, US

History

*Abbreviation of lost work, any work which is known to have bee ...

, which is said to have anticipated the ideas of John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

. His anatomical

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having it ...

pursuits probably date from an earlier period. They illustrate his versatility and thirst for knowledge, but are otherwise not significant. His claim to have anticipated William Harvey's discovery rests on no better authority than a memorandum, probably copied from Andreas Caesalpinus or Harvey himself, with whom, as well as with Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

and William Gilbert, Sarpi corresponded. The only physiological

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemica ...

discovery which can be safely attributed to him is that of the contractility of the iris.

Sarpi wrote on projectile motion in the period 1578–84, in the tradition of Niccolò Fontana Tartaglia; and then again in reporting on Guidobaldo del Monte's ideas in 1592, possibly by then having met Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He ...

. Galileo corresponded with him. Sarpi heard of the telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to obse ...

in November 1608, perhaps before Galileo. Details then came to Sarpi from Giacomo Badoer in Paris, in a letter describing the configuration of lenses. In 1609, the Venetian Republic had a telescope on approval for military purposes, but Sarpi had them turn it down, anticipating the better model Galileo had made and brought later that year.

Further reading

Sarpi's life was first recounted in a laudatory memorial tribute by his secretary and successor,Fulgenzio Micanzio Fulgenzio Micanzio (1570 in Passirano – 1654 in Venice) was a Lombardic Servite friar and theologian. A close associate of Paolo Sarpi, he undertook correspondence for Sarpi and became his biographer. He also was a supporter of Galileo Galil ...

and much of our information about him comes from this. Several biographies dating from the nineteenth century include that by Arabella Georgina Campbell (1869), with references to manuscripts, Pietro Balan

Pietro Balan (September 3, 1840 – 1893) was an Italian Catholic journalist and historian. He used newly opened Vatican archive material to write about the Reformation.

Life

He was born at Este, Veneto on 3 September 1840, and was educated in th ...

's ''Fra Paolo Sarpi'' (Venice, 1887), and Alessandro Pascolato, ''Fra Paolo Sarpi'' (Milan, 1893). The late William James Bouwsma's ''Venice and the Defense of Republican Liberty: Renaissance Values in the Age of the Counter-Reformation'' (968

Year 968 ( CMLXVIII) was a leap year starting on Wednesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place Byzantine Empire

* Emperor Nikephoros II receives a Bulgarian embassy led by Prince Boris ( ...

Yale University Press; re-issued by the University of California Press, 1984) arose initially from Bouwsma's interest in Sarpi. Its central chapters concern Sarpi' life and works, including a lengthy analysis of the style and content of his ''History of the Council of Trent''. Bouwsma's final publication, ''The Waning of the Renaissance, 1550-1640'' (Yale University Press, 2002) also deals extensively with Sarpi.

See also

* Baldassarre Capra *Edwin Sandys (American colonist)

Sir Edwin Sandys ( ; 9 December 1561 – October 1629) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1589 and 1626. He was also one of the founders of the proprietary Virginia Company of London, which in 16 ...

* Henry Wotton

* William Bedell

Notes

References

*Select Bibliography

*Kainulainen, Jaska (2014). ''Paolo Sarpi: A Servant of God and State''. Brill, 2014. *de Vivo, Filippo (2006). “Paolo Sarpi and the Uses of Information in Seventeenth-Century Venice”, pp. 35–49. In Raymond, Joad, ed. ''News Networks in Seventeenth Century Britain and Europe''. Routledge. *Wootton, David (1983). ''Paolo Sarpi: Between Renaissance and Enlightenment''. Cambridge University Press *Lievsay, John Leon (1973). ''Venetian Phoenix: Paolo Sarpi and Some of His English Friends'' (1606–1700). Wichita: University Press of Kansas. * Bouwsma, William James (1984, 1968). ''Venice and the Defense of Republican Liberty: Renaissance Values in the Age of the Counter-Reformation''. University of California Press. * Burke, Peter, editor and translator (1962). ''The History of Benefices and Selections from the History of the Council of Trent, by Paolo Sarpi''. New York: Washington Square Press. * Frances A. Yates (1944). "Paolo Sarpi's History of the Council of Trent". ''Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes'' 7:123–143.Johnson, Samuel (1810). "Father Paul Sarpi," pp. 3–10 in ''The Works of Samuel Johnson, L.L.D., in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 10''. London: Jay Nichols and Son.

External links

*Bouwsma, William J. "Venice, Spain, and the Papacy: Paolo Sarpi and the Renaissance Tradition"

from William J. Bouwsma's ''A Usable Past: Essays in European Cultural History.'' Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sarpi, Paolo 1552 births 1623 deaths Servites Italian humanists 17th-century Italian historians Republic of Venice scientists Italian male writers 16th-century Venetian writers 16th-century male writers 17th-century Venetian writers Canon law jurists