Panopticism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The panopticon is a type of institutional building and a system of control designed by the English

The panopticon is a type of institutional building and a system of control designed by the English

Bentham's proposal for a panopticon prison met with great interest among British government officials not only because it incorporated the pleasure-pain principle developed by the

Bentham's proposal for a panopticon prison met with great interest among British government officials not only because it incorporated the pleasure-pain principle developed by the

Despite the fact that no panopticon was built during Bentham's lifetime, the principles he established on the panopticon prompted considerable discussion and debate. Shortly after Jeremy Bentham's death in 1832 his ideas were criticised by

Despite the fact that no panopticon was built during Bentham's lifetime, the principles he established on the panopticon prompted considerable discussion and debate. Shortly after Jeremy Bentham's death in 1832 his ideas were criticised by

In 1984,

In 1984,

Foucault's use of the panopticon metaphor shaped the debate on workplace surveillance in the 1970s. In 1981 the sociologist

Foucault's use of the panopticon metaphor shaped the debate on workplace surveillance in the 1970s. In 1981 the sociologist

In 1854 the work on the building that was to house the Royal Panopticon of Science and Art in

In 1854 the work on the building that was to house the Royal Panopticon of Science and Art in

philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

and social theorist Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 ld Style and New Style dates, O.S. 4 February 1747– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of modern utilitarianism.

Bentham defined as the "fundam ...

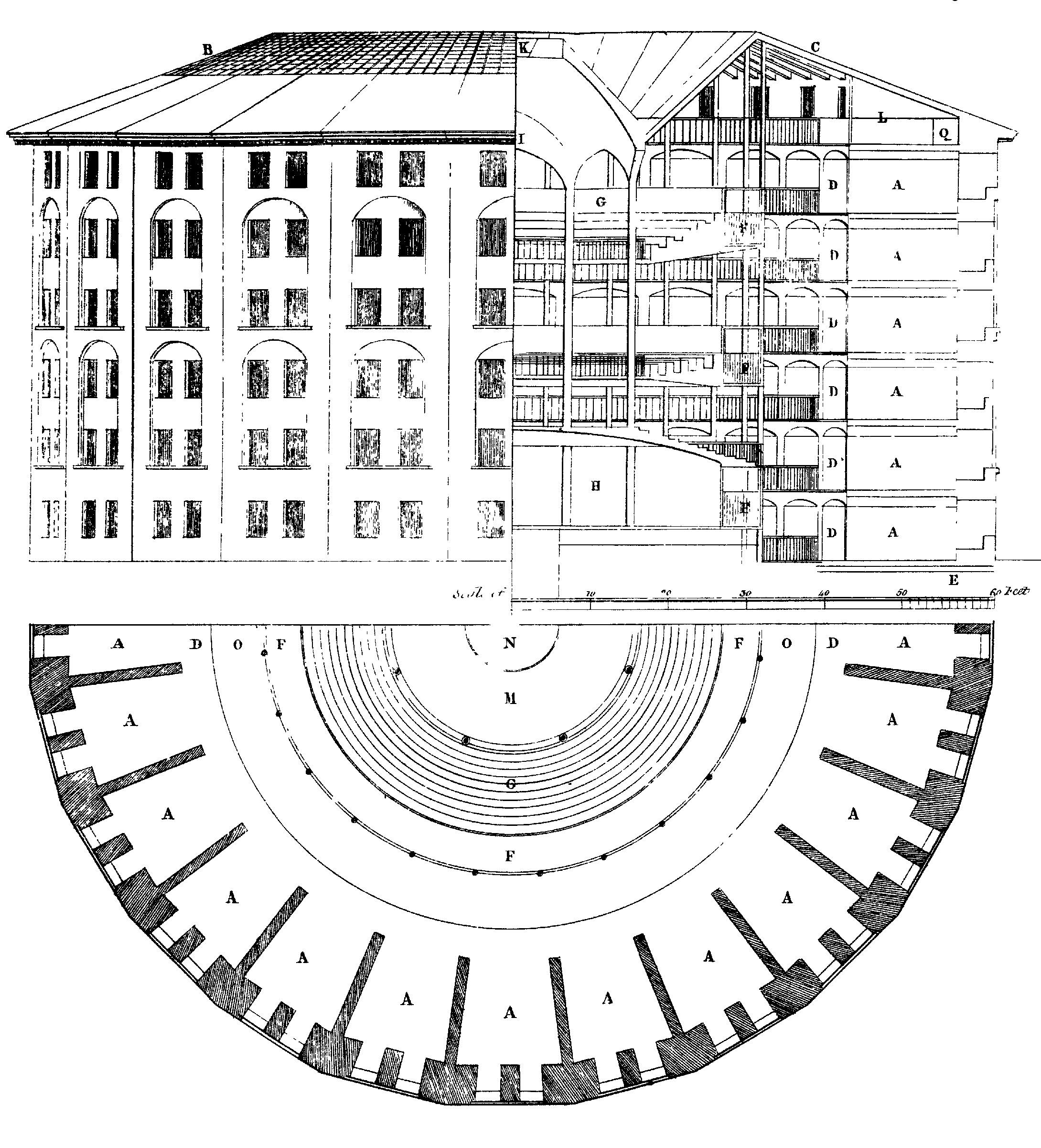

in the 18th century. The concept of the design is to allow all prisoners of an institution to be observed by a single security guard

A security guard (also known as a security inspector, security officer, or protective agent) is a person employed by a government or private party to protect the employing party's assets (property, people, equipment, money, etc.) from a variety ...

, without the inmates being able to tell whether they are being watched.

Although it is physically impossible for the single guard to observe all the inmates' cells at once, the fact that the inmates cannot know when they are being watched means that they are motivated to act as though they are being watched at all times. Thus, the inmates are effectively compelled to regulate their own behaviour. The architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

consists of a rotunda with an inspection

An inspection is, most generally, an organized examination or formal evaluation exercise. In engineering activities inspection involves the measurements, tests, and gauges applied to certain characteristics in regard to an object or activity. ...

house at its centre. From the centre, the manager or staff of the institution are able to watch the inmates. Bentham conceived the basic plan as being equally applicable to hospitals

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emerge ...

, schools

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes compulsor ...

, sanatoriums, and asylums, but he devoted most of his efforts to developing a design for a panopticon prison. It is his prison that is now most widely meant by the term "panopticon".

Conceptual history

The word ''panopticon'' derives from the Greek word for "all seeing" – . In 1785,Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 ld Style and New Style dates, O.S. 4 February 1747– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of modern utilitarianism.

Bentham defined as the "fundam ...

, an English social reformer and founder of utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different chara ...

, travelled to Krichev in Mogilev Governorate of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

(modern Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by ...

) to visit his brother, Samuel

Samuel ''Šəmūʾēl'', Tiberian: ''Šămūʾēl''; ar, شموئيل or صموئيل '; el, Σαμουήλ ''Samouḗl''; la, Samūēl is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the bib ...

, who accompanied Prince Potemkin

Prince Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin-Tauricheski (, also , ;, rus, Князь Григо́рий Алекса́ндрович Потёмкин-Таври́ческий, Knjaz' Grigórij Aleksándrovich Potjómkin-Tavrícheskij, ɡrʲɪˈɡ ...

. Bentham arrived in Krichev in early 1786 and stayed for almost two years. While residing with his brother in Krichev, Bentham sketched out the concept of the panopticon in letters. Bentham applied his brother's ideas on the constant observation of worker

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

s to prisons. Back in England, Bentham, with the assistance of his brother, continued to develop his theory on the panopticon. Prior to fleshing out his ideas of a panopticon prison, Bentham had drafted a complete penal code

A criminal code (or penal code) is a document that compiles all, or a significant amount of a particular jurisdiction's criminal law. Typically a criminal code will contain offences that are recognised in the jurisdiction, penalties that might ...

and explored fundamental legal theory. While in his lifetime Bentham was a prolific letter writer, he published little and remained obscure to the public until his death.

Bentham thought that the chief mechanism that would bring the manager of the panopticon prison in line with the duty to be humane would be publicity

In marketing, publicity is the public visibility or Brand awareness, awareness for any Product (business), product, Service (economics), service, person or organization (company, Charitable organization, charity, etc.). It may also refer to the mov ...

. Bentham tried to put his ''duty and interest junction principle'' into practice by encouraging a public debate on prisons. Bentham's ''inspection principle'' applied not only to the inmates of the panopticon prison, but also the manager. The unaccountable gaoler

A prison officer or corrections officer is a uniformed law enforcement official responsible for the custody, supervision, safety, and regulation of prisoners. They are responsible for the care, custody, and control of individuals who have been ...

was to be observed by the general public and public officials. The apparently constant surveillance of the prison inmates by the panopticon manager and the occasional observation of the manager by the general public was to solve the age old philosophic question: " Who guards the guards?"

Bentham continued to develop the panopticon concept, as industrialisation

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

advanced in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

and an increasing number of workers were required to work in ever larger factories

A factory, manufacturing plant or a production plant is an industrial facility, often a complex consisting of several buildings filled with machinery, where workers manufacture items or operate machines which process each item into another. T ...

. Bentham commissioned drawings from an architect, Willey Reveley

Willey Reveley (1760–1799) was an 18th-century English architect, born at Newton Underwood near Morpeth, Northumberland.

He was a pupil of Sir William Chambers,

and was trained at the Royal Academy Schools. In 1781-2 he was employed (under ...

. Bentham reasoned that if the prisoners of the panopticon prison could be seen but never knew when they were watched, the prisoners would need to follow the rules. Bentham also thought that Reveley's prison design could be used for factories

A factory, manufacturing plant or a production plant is an industrial facility, often a complex consisting of several buildings filled with machinery, where workers manufacture items or operate machines which process each item into another. T ...

, asylum

Asylum may refer to:

Types of asylum

* Asylum (antiquity), places of refuge in ancient Greece and Rome

* Benevolent Asylum, a 19th-century Australian institution for housing the destitute

* Cities of Refuge, places of refuge in ancient Judea

...

s, hospitals

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emerge ...

, and school

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes co ...

s.

Bentham remained bitter throughout his later life about the rejection of the panopticon scheme, convinced that it had been thwarted by the king and an aristocratic elite. It was largely because of his sense of injustice and frustration that he developed his ideas of ''sinister interest'' – that is, of the vested interests of the powerful conspiring against a wider public interest – which underpinned many of his broader arguments for reform.

Prison design

Bentham's proposal for a panopticon prison met with great interest among British government officials not only because it incorporated the pleasure-pain principle developed by the

Bentham's proposal for a panopticon prison met with great interest among British government officials not only because it incorporated the pleasure-pain principle developed by the materialist

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds matter to be the fundamental substance in nature, and all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. According to philosophical materiali ...

philosopher Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5/15 April 1588 – 4/14 December 1679) was an English philosopher, considered to be one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book '' Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influ ...

, but also because Bentham joined the emerging discussion on political economy

Political economy is the study of how economic systems (e.g. markets and national economies) and political systems (e.g. law, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied phenomena within the discipline are systems such as labour ...

. Bentham argued that the confinement of the prison, "which is his punishment, preventing he prisoner fromcarrying the work to another market." Key to Bentham's proposals and efforts to build a panopticon prison in Millbank at his own expense, was the "means of extracting labour" out of prisoners in the panopticon. In his 1791 writing ''Panopticon, or The Inspection House'', Bentham reasoned that those working fixed hours needed to be overseen. Also, in 1791, Jean Philippe Garran de Coulon presented a paper on Bentham's panopticon prison concepts to the National Legislative Assembly in revolutionary France.

In 1812, persistent problems with Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

and other London prisons prompted the British government to fund the construction of a prison in Millbank at the taxpayers' expense. Based on Bentham's panopticon plans, the National Penitentiary opened in 1821. Millbank Prison, as it became known, was controversial, even blamed for causing mental illness among prisoners. Nevertheless, the British government placed an increasing emphasis on prisoners doing meaningful work, instead of engaging in humiliating and meaningless kill-times. Bentham lived to see Millbank Prison built and did not support the approach taken by the British government. His writings had virtually no immediate effect on the architecture of taxpayer-funded prisons that were to be built. Between 1818 and 1821, a small prison for women was built in Lancaster. It has been observed that the architect Joseph Gandy

Joseph Michael Gandy (1771–1843) was an English artist, visionary architect and architectural theorist, most noted for his imaginative paintings depicting Sir John Soane's architectural designs. He worked extensively with Soane both as ...

modelled it very closely on Bentham's panopticon prison plans. The K-wing near Lancaster Castle prison is a semi-rotunda with a central tower for the supervisor and five storeys with nine cells on each floor.

It was the Pentonville prison

HM Prison Pentonville (informally "The Ville") is an English Category B men's prison, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service. Pentonville Prison is not in Pentonville, but is located further north, on the Caledonian Road in the Barnsbury ar ...

, which was built in London after Bentham's death in 1832, that was to serve as a model for a further 54 prisons in Victorian Britain. Built between 1840 and 1842 according to the plans of Joshua Jebb

Sir Joshua Jebb, (8 May 1793 – 26 June 1863) was a Royal Engineer and the British Surveyor-General of convict prisons.

He participated in the Battle of Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain during the War of 1812, and surveyed a route between Ottawa ...

, Pentonville prison had a central hall with radial prison wings. It has been claimed that Bentham's panopticon influenced the radial design of 19th-century prisons built on the principles of the "separate system

The separate system is a form of prison management based on the principle of keeping prisoners in solitary confinement. When first introduced in the early 19th century, the objective of such a prison or "penitentiary" was that of penance by the p ...

", including Eastern State Penitentiary

The Eastern State Penitentiary (ESP) is a former American prison in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is located at 2027 Fairmount Avenue between Corinthian Avenue and North 22nd Street in the Fairmount section of the city, and was operational from ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

, which opened in 1829. But the Pennsylvania–Pentonville architectural model with its radial prison wings was not designed to facilitate constant surveillance of individual prisoners. Guards had to walk from the hall along the radial corridors and could only observe prisoners in their cells by looking through the cell door's peephole.

In 1925, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

's president Gerardo Machado

Gerardo Machado y Morales (28 September 1869 – 29 March 1939) was a general of the Cuban War of Independence and President of Cuba from 1925 to 1933.

Machado entered the presidency with widespread popularity and support from the major polit ...

set out to build a modern prison, based on Bentham's concepts and employing the latest scientific theories on rehabilitation

Rehabilitation or Rehab may refer to:

Health

* Rehabilitation (neuropsychology), therapy to regain or improve neurocognitive function that has been lost or diminished

* Rehabilitation (wildlife), treatment of injured wildlife so they can be retur ...

. A Cuban envoy tasked with studying US prisons

Incarceration in the United States is a primary form of punishment and rehabilitation for the commission of felony and other offenses. The United States has the largest prison population in the world, and the highest per-capita incarcerati ...

in advance of the construction of Presidio Modelo had been greatly impressed with Stateville Correctional Center

Stateville Correctional Center (SCC) is a maximum security state prison for men in Crest Hill, Illinois, United States, near Chicago. It is a part of the Illinois Department of Corrections.

History

Opened in 1925, Stateville was built to ...

in Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

and the cells in the new circular prison were too faced inwards towards a central guard tower. Because of the shuttered guard tower, the guards could see the prisoners, but the prisoners could not see the guards. Cuban officials theorised that the prisoners would "behave" if there was a probable chance that they were under surveillance

Surveillance is the monitoring of behavior, many activities, or information for the purpose of information gathering, influencing, managing or directing. This can include observation from a distance by means of electronic equipment, such as ...

, and once prisoners behaved, they could be rehabilitated.

Between 1926 and 1931, the Cuban government built four such panopticons connected with tunnels to a massive central structure that served as a community centre. Each panopticon had five floors with 93 cells. In keeping with Bentham's ideas, none of the cells had doors. Prisoners were free to roam the prison and participate in workshops to learn a trade or become literate, with the hope being that they would become productive citizen

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

s. However, by the time Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 20 ...

was imprisoned at Presidio Modelo, the four circulars were packed with 6,000 men, every floor was filled with trash, there was no running water, food rations were meagre, and the government supplied only the bare necessities of life.

In the Netherlands Breda

Breda () is a city and municipality in the southern part of the Netherlands, located in the province of North Brabant. The name derived from ''brede Aa'' ('wide Aa' or 'broad Aa') and refers to the confluence of the rivers Mark and Aa. Breda has ...

, Arnhem

Arnhem ( or ; german: Arnheim; South Guelderish: ''Èrnem'') is a city and municipality situated in the eastern part of the Netherlands about 55 km south east of Utrecht. It is the capital of the province of Gelderland, located on both ban ...

and Haarlem penitentiary are cited as historic panopticon prisons. However, these circular prisons with their 400 or so cells fail as panopticons because the inwards-facing cell windows were so small that guards could not see the entire cell. The lack of surveillance that was actually possible in prisons with small cells and doors discounts many circular prison designs from being a panopticon as it had been envisaged by Bentham. In 2006, one of the first digital panopticon prisons opened near Amsterdam. Every prisoner in the Lelystad Prison wears an electronic tag

Electronic tagging is a form of surveillance that uses an electronic device affixed to a person.

In some jurisdictions, an electronic tag fitted above the ankle is used for people as part of their bail or probation conditions. It is also used i ...

and by design, only six guards are needed for 150 prisoners instead of the usual 15 or more.

Architecture of other institutions

Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 ld Style and New Style dates, O.S. 4 February 1747– 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of modern utilitarianism.

Bentham defined as the "fundam ...

's panopticon architecture was not original, as rotundas

A rotunda () is any building with a circular ground plan, and sometimes covered by a dome. It may also refer to a round room within a building (a famous example being the one below the dome of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.). Th ...

had been used before, as for example in industrial buildings. However, Bentham turned the rotund architecture into a structure with a societal function, so that humans themselves became the object of control. The idea for a panopticon had been prompted by his brother Samuel Bentham's work in Russia and had been inspired by existing architectural traditions. Samuel Bentham had studied at the Ecole Militaire in 1751, and at about 1773 the prominent French architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux had finished his designs for the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans. William Strutt in cooperation with his friend Jeremy Bentham built a round mill in Belper

Belper is a town and civil parish in the local government district of Amber Valley in Derbyshire, England, located about north of Derby on the River Derwent. As well as Belper itself, the parish also includes the village of Milford and the ...

, so that one supervisor could oversee an entire shop floor from the centre of the round mill. The mill was built between 1803 and 1813 and was used for production until the late 19th century. It was demolished in 1959. In Bentham's 1812 writing ''Pauper management improved: particularly by means of an application of the Panopticon principle of construction'', he included a building for an "industry-house establishment" that could hold 2000 persons. In 1812 Samuel Bentham, who had by then risen to brigardier-general, tried to persuade the British Admiralty

The Admiralty was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for the command of the Royal Navy until 1964, historically under its titular head, the Lord High Admiral – one of the Great Officers of State. For much of i ...

to construct an arsenal

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are mostl ...

panopticon in Kent. Before returning home to London he had constructed a panopticon in 1807, near St Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, which served as a training centre for young men wishing to work in naval manufacturing. The panopticon, Bentham writes:

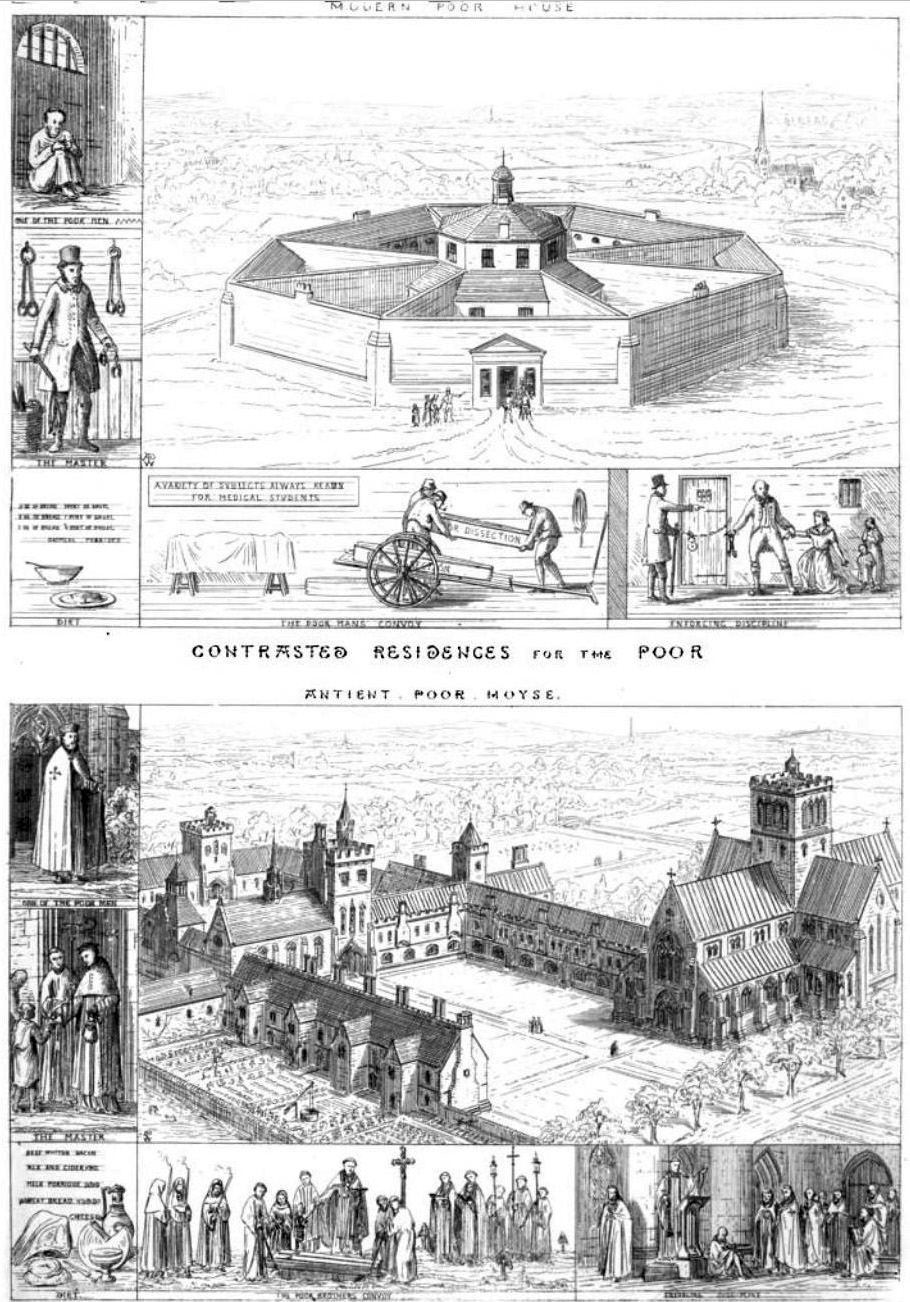

Despite the fact that no panopticon was built during Bentham's lifetime, the principles he established on the panopticon prompted considerable discussion and debate. Shortly after Jeremy Bentham's death in 1832 his ideas were criticised by

Despite the fact that no panopticon was built during Bentham's lifetime, the principles he established on the panopticon prompted considerable discussion and debate. Shortly after Jeremy Bentham's death in 1832 his ideas were criticised by Augustus Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 181214 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and, ultimately, Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival st ...

, who in 1841 published the second edition of his work '' Contrasts'' in which one plate showed a "Modern Poor House". He contrasted an English medieval gothic town in 1400 with the same town in 1840 where broken spire

A spire is a tall, slender, pointed structure on top of a roof of a building or tower, especially at the summit of church steeples. A spire may have a square, circular, or polygonal plan, with a roughly conical or pyramidal shape. Spires a ...

s and factory chimney

A chimney is an architectural ventilation structure made of masonry, clay or metal that isolates hot toxic exhaust gases or smoke produced by a boiler, stove, furnace, incinerator, or fireplace from human living areas. Chimneys are typ ...

s dominate the skyline, with a panopticon in the foreground replacing the Christian hospice

Hospice care is a type of health care that focuses on the palliation of a terminally ill patient's pain and symptoms and attending to their emotional and spiritual needs at the end of life. Hospice care prioritizes comfort and quality of life b ...

. Pugin, who went on to become one of the most influential 19th-century writers on architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

, was influenced by Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends a ...

and German idealism

German idealism was a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutiona ...

. In 1835 the first annual report of the Poor Law Commission included two designs by the commission's architect Sampson Kempthorne

Sampson Kempthorne (1809–1873) was an English architect who specialised in the design of workhouses, before his emigration to New Zealand.

Life

He was the son of Rev. John Kempthorne. He began practising in Carlton Chambers on Regent Street ...

. His Y-shape and cross-shape designs for workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse' ...

expressed the panopticon principle by positioning the master's room as central point. The designs provided for the segregation of occupants and maximum visibility from the centre. Professor David Rothman came to the conclusion that Bentham's panopticon prison did not inform the architecture of early asylums in the United States.

Criticism and use as metaphor

In 1965, the conservative historian Shirley Robin Letwin traced the Fabian zest for social planning to early utilitarian thinkers. She argued that Bentham's pet gadget, the panopticon prison, was a device of such monstrous efficiency that it left no room for humanity. She accused Bentham of forgetting the dangers of unrestrained power and argued that "in his ardour for reform, Bentham prepared the way for what he feared". RecentLibertarian

Libertarianism (from french: libertaire, "libertarian"; from la, libertas, "freedom") is a political philosophy that upholds liberty as a core value. Libertarians seek to maximize autonomy and political freedom, and minimize the state's en ...

thinkers began to regard Bentham's entire philosophy as having paved the way for totalitarian state

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and regul ...

s. In the late 1960s, the American historian Gertrude Himmelfarb

Gertrude Himmelfarb (August 8, 1922 – December 30, 2019), also known as Bea Kristol, was an American historian. She was a leader of conservative interpretations of history and historiography. She wrote extensively on intellectual history, ...

, who had published ''The Haunted House of Jeremy Bentham'' in 1965, was at the forefront of depicting Bentham's mechanism of surveillance as a tool of oppression and social control. David John Manning published ''The Mind of Jeremy Bentham'' in 1986, in which he reasoned that Bentham's fear of instability caused him to advocate ruthless social engineering and a society in which there could be no privacy

Privacy (, ) is the ability of an individual or group to seclude themselves or information about themselves, and thereby express themselves selectively.

The domain of privacy partially overlaps with security, which can include the concepts of ...

or tolerance

Tolerance or toleration is the state of tolerating, or putting up with, conditionally.

Economics, business, and politics

* Toleration Party, a historic political party active in Connecticut

* Tolerant Systems, the former name of Veritas Software ...

for the deviant.

In the mid-1970s, the panopticon was brought to the wider attention by the French psychoanalyst Jacques-Alain Miller

Jacques-Alain Miller (; born 14 February 1944) is a psychoanalyst and writer. He is one of the founder members of the École de la Cause freudienne (School of the Freudian Cause) and the World Association of Psychoanalysis which he presided from ...

and the French philosopher Michel Foucault

Paul-Michel Foucault (, ; ; 15 October 192625 June 1984) was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, writer, political activist, and literary critic. Foucault's theories primarily address the relationship between power and knowledge, and ho ...

. In 1975, Foucault used the panopticon as metaphor for the modern disciplinary society in '' Discipline and Punish''. He argued that the disciplinary society had emerged in the 18th century and that discipline are techniques for assuring the ordering of human complexities, with the ultimate aim of docility and utility in the system. Foucault first came across the panopticon architecture when he studied the origins of clinical medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care practice ...

and hospital architecture in the second half of the 18th century. He argued that discipline had replaced the pre-modern society of kings, and that the panopticon should not be understood as a building, but as a mechanism of power and a diagram of political technology.

Foucault argued that discipline had already crossed the technological threshold in the late 18th century, when the right to observe and accumulate knowledge had been extended from the prison to hospitals, schools, and later factories. In his historic analysis, Foucault reasoned that with the disappearance of public execution

A public execution is a form of capital punishment which "members of the general public may voluntarily attend." This definition excludes the presence of only a small number of witnesses called upon to assure executive accountability. The purpose ...

s pain had been gradually eliminated as punishment

Punishment, commonly, is the imposition of an undesirable or unpleasant outcome upon a group or individual, meted out by an authority—in contexts ranging from child discipline to criminal law—as a response and deterrent to a particular ac ...

in a society ruled by reason. The modern prison in the 1970s, with its corrective technology, was rooted in the changing legal powers of the state. While acceptance for corporal punishment diminished, the state gained the right to administer more subtle methods of punishment, such as to observe. The French sociologist Henri Lefebvre

Henri Lefebvre ( , ; 16 June 1901 – 29 June 1991) was a French Marxist philosopher and sociologist, best known for pioneering the critique of everyday life, for introducing the concepts of the right to the city and the production of s ...

studied urban space

An urban area, built-up area or urban agglomeration is a human settlement with a high population density and infrastructure of built environment. Urban areas are created through urbanization and are categorized by urban morphology as cities, ...

and Foucault's interpretation of the panopticon prison, arriving at the conclusion that spatiality is a social phenomenon. Lefebvre contended that architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

is no more than the relationship between the panopticon, people, and objects. In urban studies

Urban studies is based on the study of the urban development of cities. This includes studying the history of city development from an architectural point of view, to the impact of urban design on community development efforts. The core theoretica ...

, academics such as Marc Schuilenburg now argue that a different self-consciousness arises among humans who live in an urban area.

In 1984,

In 1984, Michael Radford

Michael James Radford (born 24 February 1946) is an English film director and screenwriter. He began his career as a documentary director and television comedy writer before transitioning into features in the early 1980s. His best-known credits ...

gained international attention for the cinematographic panopticon he had staged in the film ''Nineteen Eighty-Four''. Of the telescreen

Telescreens are devices that operate simultaneously as televisions, security cameras, and microphones. They are featured in George Orwell's dystopian 1949 novel ''Nineteen Eighty-Four'' as well as all film adaptations of the novel. In the novel a ...

s in the landmark surveillance narrative ''Nineteen Eighty-Four

''Nineteen Eighty-Four'' (also stylised as ''1984'') is a dystopian social science fiction novel and cautionary tale written by the English writer George Orwell. It was published on 8 June 1949 by Secker & Warburg as Orwell's ninth and fina ...

'' (1949), George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalit ...

said: "there was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment ... you had to live ... in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinised". In Radford's film the telescreens were bidirectional and in a world with an ever increasing number of telescreen devices the citizens of Oceania were spied on more than they thought possible. In ''The Electronic Eye: The Rise of Surveillance Society'' (1994) the sociologist David Lyon concluded that "no single metaphor or model is adequate to the task of summing up what is central to contemporary surveillance, but important clues are available in ''Nineteen Eighty-Four'' and in Bentham's panopticon".

The French philosopher Gilles Deleuze

Gilles Louis René Deleuze ( , ; 18 January 1925 – 4 November 1995) was a French philosopher who, from the early 1950s until his death in 1995, wrote on philosophy, literature, film, and fine art. His most popular works were the two volu ...

shaped the emerging field of surveillance studies with the 1990 essay ''Postscript on the Societies of Control''. Deleuze argued that the society of control is replacing the discipline society. With regards to the panopticon, Deleuze argued that "enclosures are moulds ... but controls are a modulation". Deleuze observed that technology had allowed physical enclosures, such as schools, factories, prisons and office buildings, to be replaced by a self-governing machine, which extends surveillance

Surveillance is the monitoring of behavior, many activities, or information for the purpose of information gathering, influencing, managing or directing. This can include observation from a distance by means of electronic equipment, such as ...

in a quest to manage production and consumption. Information circulates in the control society, just like products in the modern economy, and meaningful objects of surveillance are sought out as forward-looking profiles and simulated pictures of future demands, needs and risks are drawn up.

In 1997, Thomas Mathiesen

Thomas Mathiesen (5 October 1933 – 29 May 2021) was a Norwegian sociologist.

Background

Mathiesen grew up in the Norwegian county of Akershus, as the only child of Einar Mathiesen (1903–1983) and Birgit Mathiesen (1908–1990).Mathiesen, ...

in turn expanded on Foucault's use of the panopticon metaphor when analysing the effects of mass media

Mass media refers to a diverse array of media technologies that reach a large audience via mass communication. The technologies through which this communication takes place include a variety of outlets.

Broadcast media transmit informati ...

on society. He argued that mass media such as broadcast television

Broadcast television systems (or terrestrial television systems outside the US and Canada) are the encoding or formatting systems for the transmission and reception of terrestrial television signals.

Analog television systems were standardized b ...

gave many people the ability to view the few from their own homes and gaze upon the lives of reporters and celebrities

Celebrity is a condition of fame and broad public recognition of a person or group as a result of the attention given to them by mass media. An individual may attain a celebrity status from having great wealth, their participation in sports ...

. Mass media has thus turned the discipline society into a viewer society. In the 1998 satirical science fiction film ''The Truman Show

''The Truman Show'' is a 1998 American psychological satirical comedy-drama film directed by Peter Weir, produced by Scott Rudin, Andrew Niccol, Edward S. Feldman, and Adam Schroeder, and written by Niccol. The film stars Jim Carrey as Tr ...

'', the protagonist eventually escapes the OmniCam Ecosphere, the reality television

Reality television is a genre of television programming that documents purportedly unscripted real-life situations, often starring unfamiliar people rather than professional actors. Reality television emerged as a distinct genre in the early 1 ...

show that, unknown to him, broadcasts his life around the clock and across the globe. But in 2002, Peter Weibel noted that the entertainment industry

Entertainment is a form of activity that holds the attention and interest of an audience or gives pleasure and delight. It can be an idea or a task, but is more likely to be one of the activities or events that have developed over thousan ...

does not consider the panopticon as a threat or punishment, but as "amusement, liberation and pleasure". With reference to the ''Big Brother'' television shows of Endemol Entertainment

Endemol B.V. was a Dutch-based media company that produced and distributed multiplatform entertainment content. The company annually produced more than 15,000 hours of programming across scripted and non-scripted genres, including drama, reality ...

, in which a group of people live in a container studio apartment and allow themselves to be recorded constantly, Weibel argued that the panopticon provides the masses with "the pleasure of power, the pleasure of sadism, voyeurism, exhibitionism, scopophilia, and narcissism". In 2006, Shoreditch TV became available to residents of the Shoreditch

Shoreditch is a district in the East End of London in England, and forms the southern part of the London Borough of Hackney. Neighbouring parts of Tower Hamlets are also perceived as part of the area.

In the 16th century, Shoreditch was an imp ...

in London, so that they could tune in to watch CCTV footage live. The service allowed residents "to see what's happening, check out the traffic and keep an eye out for crime".

In their 2004 book ''Welcome to the Machine: Science, Surveillance, and the Culture of Control'', Derrick Jensen and George Draffan called Bentham "one of the pioneers of modern surveillance" and argued that his panopticon prison design serves as the model for modern supermaximum security prisons, such as Pelican Bay State Prison

Pelican Bay State Prison (PBSP) is a supermax prison facility in Crescent City, California. The prison takes its name from a shallow bay on the Pacific coast, about to the west.

Facilities

The prison is located in a detached section of Cre ...

in California. In the 2015 book ''Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness'', Simone Browne

Simone Arlene Browne (born 1973) is an author and educator. She is on the faculty at the University of Texas at Austin, and the author of ''Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness''.

Early life and education

Browne was born in 1973, an ...

noted that Bentham travelled on a ship carrying slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

as cargo while drafting his panopticon proposal. She argues that the structure of chattel slavery haunts the theory of the panopticon. She proposes that the 1789 plan of the slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast ...

''Brookes

Brookes is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Barbara Brookes, New Zealand historian

* Bruno Brookes, English broadcaster

* Dennis Brookes, English cricketer

* Ed Brookes (1881–1958), Irish international soccer player

* ...

'' should be regarded as the paradigmatic blueprint. Drawing on Didier Bigo Didier Bigo (born 31 August 1956) is a French academic from Lille and Professor of International Relations at King's College London and at Sciences Po, Paris. He has authored two books, ''Polices en réseaux. L'expérience européenne'' (1996) and ' ...

's Banopticon, Brown argues that society is ruled by exceptionalism of power, where the state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

becomes permanent and certain groups are excluded on the basis of their future potential behaviour as determined through profiling.

Surveillance technology

The metaphor of the panopticon prison has been employed to analyse the social significance ofsurveillance

Surveillance is the monitoring of behavior, many activities, or information for the purpose of information gathering, influencing, managing or directing. This can include observation from a distance by means of electronic equipment, such as ...

by closed-circuit television

Closed-circuit television (CCTV), also known as video surveillance, is the use of video cameras to transmit a signal to a specific place, on a limited set of monitors. It differs from broadcast television in that the signal is not openly tr ...

(CCTV) cameras in public spaces. In 1990, Mike Davis reviewed the design and operation of a shopping mall

A shopping mall (or simply mall) is a North American term for a large indoor shopping center, usually Anchor tenant, anchored by department stores. The term "mall" originally meant pedestrian zone, a pedestrian promenade with shops along it (that ...

, with its centralised control room, CCTV cameras and security guards, and came to the conclusion that it "plagiarizes brazenly from Jeremy Bentham's renowned nineteenth-century design". In their 1996 study of CCTV camera installations in British cities, Nicholas Fyfe and Jon Bannister called central and local government policies that facilitated the rapid spread of CCTV surveillance a dispersal of an "electronic panopticon". Particular attention has been drawn to the similarities of CCTV with Bentham's prison design because CCTV technology enabled, in effect, a central observation tower, staffed by an unseen observer.

Employment and management

Shoshana Zuboff

Shoshana Zuboff (born 18 November 1951) is an American author, Harvard professor, social psychologist, philosopher, and scholar.

Zuboff is the author of the books ''In the Age of the Smart Machine: The Future of Work and Power'' and ''The Suppo ...

used the metaphor of the panopticon in her 1988 book ''In the Age of the Smart Machine: The Future of Work and Power'' to describe how computer technology makes work more visible. Zuboff examined how computer systems were used for employee monitoring

Employee monitoring is the (often automated) surveillance of workers' activity. Organizations engage in employee monitoring for different reasons such as to track performance, to avoid legal liability, to protect trade secrets, and to address other ...

to track the behavior and output of workers. She used the term 'panopticon' because the workers could not tell that they were being spied on, while the manager was able to check their work continuously. Zuboff argued that there is a collective responsibility formed by the hierarchy in the ''information panopticon'' that eliminates subjective opinions and judgements of managers on their employees. Because each employee's contribution to the production process is translated into objective data, it becomes more important for managers to be able to analyze the work rather than analyze the people.

Anthony Giddens

Anthony Giddens, Baron Giddens (born 18 January 1938) is an English sociologist who is known for his theory of structuration and his holistic view of modern societies. He is considered to be one of the most prominent modern sociologists and is ...

expressed scepticism about the ongoing surveillance debate, criticising that "Foucault's 'archaeology', in which human beings do not make their own history but are swept along by it, does not adequately acknowledge that those subject to the power ... are knowledgeable agents, who resist, blunt or actively alter the conditions of life." The social alienation

Social alienation is a person's feeling of disconnection from a group whether friends, family, or wider society to which the individual has an affinity. Such alienation has been described as "a condition in social relationships reflected by (1) ...

of workers and management in the industrialised production process had long been studied and theorised. In the 1950s and 1960s, the emerging behavioural science approach led to skills testing and recruitment processes that sought out employees that would be organisationally committed. Fordism

Fordism is a manufacturing technology that serves as the basis of modern economic and social systems in industrialized, standardized mass production and mass consumption. The concept is named after Henry Ford. It is used in social, economic, and ...

, Taylorism

Scientific management is a theory of management that analyzes and synthesizes workflows. Its main objective is improving economic efficiency, especially labor productivity. It was one of the earliest attempts to apply science to the engineeri ...

and bureaucratic management of factories was still assumed to reflect a mature industrial society. The Hawthorne Plant experiments (1924–1933) and a significant number of subsequent empirical studies led to the reinterpretation of alienation: instead of being a given power relationship between the worker and management, it came to be seen as hindering progress and modernity. The increasing employment in the service industries

Service industries are those not directly concerned with the production of physical goods (such as agriculture and manufacturing).

Some service industries, including transportation, wholesale trade and retail trade are part of the supply chain de ...

has also been re-evaluated. In ''Entrapped by the electronic panopticon? Worker resistance in the call centre'' (2000), Phil Taylor and Peter Bain argue that the large number of people employed in call centres

A call centre ( Commonwealth spelling) or call center ( American spelling; see spelling differences) is a managed capability that can be centralised or remote that is used for receiving or transmitting a large volume of enquiries by telephone ...

undertake predictable and monotonous work that is badly paid and offers few prospects. As such, they argue, it is comparable to factory work.

The panopticon has become a symbol of the extreme measures that some companies take in the name of efficiency as well as to guard against employee theft. ''Time-theft'' by workers has become accepted as an output restriction and theft

Theft is the act of taking another person's property or services without that person's permission or consent with the intent to deprive the rightful owner of it. The word ''theft'' is also used as a synonym or informal shorthand term for som ...

has been associated by management with all behaviour that include avoidance of work. In the past decades "unproductive behaviour" has been cited as rationale for introducing a range of surveillance techniques and the vilification of employees who resist them. In a 2009 paper by Max Haiven and Scott Stoneman entitled ''Wal-Mart

Walmart Inc. (; formerly Wal-Mart Stores, Inc.) is an American multinational retail corporation that operates a chain of hypermarkets (also called supercenters), discount department stores, and grocery stores from the United States, headquarter ...

: The Panopticon of Time'' and the 2014 book by Simon Head ''Mindless: Why Smarter Machines Are Making Dumber Humans'', which describes conditions at an Amazon

Amazon most often refers to:

* Amazons, a tribe of female warriors in Greek mythology

* Amazon rainforest, a rainforest covering most of the Amazon basin

* Amazon River, in South America

* Amazon (company), an American multinational technolog ...

depot in Augsburg

Augsburg (; bar , Augschburg , links=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swabian_German , label=Swabian German, , ) is a city in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, around west of Bavarian capital Munich. It is a university town and regional seat of the ' ...

, it is argued that catering at all times to the desires of the customer can lead to increasingly oppressive corporate environments and quotas

Quota may refer to:

Economics

* Import quota, a trade restriction on the quantity of goods imported into a country

* Market Sharing Quota, an economic system used in Canadian agriculture

* Milk quota, a quota on milk production in Europe

* Indi ...

in which many warehouse workers can no longer keep up with demands of management.

Social media

The concept of panopticon has been referenced in early discussions about the impact ofsocial media

Social media are interactive media technologies that facilitate the creation and sharing of information, ideas, interests, and other forms of expression through virtual communities and networks. While challenges to the definition of ''social me ...

. The notion of ''dataveillance'' was coined by Roger Clarke in 1987, since then academic researchers have used expressions such as ''superpanopticon'' ( Mark Poster 1990), ''panoptic sort'' ( Oscar H. Gandy Jr. 1993) and ''electronic panopticon'' ( David Lyon 1994) to describe social media. Because the controlled is at the center and surrounded by those who watch, early surveillance studies treat social media as a reverse panopticon.

In modern academic literature on social media, terms like ''lateral surveillance'', ''social searching'', and ''social surveillance'' are employed to critically evaluate the effects of social media. However, the sociologist Christian Fuchs

Christian Fuchs (; born 7 April 1986) is an Austrian former professional footballer who played as a left back.

He began his senior career as a teenager at Wiener Neustadt before signing his first professional contract at 17 with SV Mattersburg ...

treats social media like a classical panopticon. He argues that the focus should not be on the relationship between the users of a medium, but the relationship between the users and the medium. Therefore, he argues that the relationship between the large number of users and the sociotechnical Web 2.0

Web 2.0 (also known as participative (or participatory) web and social web) refers to websites that emphasize user-generated content, ease of use, participatory culture and interoperability (i.e., compatibility with other products, systems, and ...

platform, like Facebook

Facebook is an online social media and social networking service owned by American company Meta Platforms. Founded in 2004 by Mark Zuckerberg with fellow Harvard College students and roommates Eduardo Saverin, Andrew McCollum, Dust ...

, amounts to a panopticon. Fuchs draws attention to the fact that use of such platforms requires identification, classification and assessment of users by the platforms and therefore, he argues, the definition of privacy

Privacy (, ) is the ability of an individual or group to seclude themselves or information about themselves, and thereby express themselves selectively.

The domain of privacy partially overlaps with security, which can include the concepts of ...

must be reassessed to incorporate stronger consumer protection

Consumer protection is the practice of safeguarding buyers of goods and services, and the public, against unfair practices in the marketplace. Consumer protection measures are often established by law. Such laws are intended to prevent business ...

and protection of citizens from corporate surveillance

Corporate surveillance is the monitoring of a person or group's behavior by a corporation. The data collected is most often used for marketing purposes or sold to other corporations, but is also regularly shared with government agencies. It can b ...

.

The arts and literature

According to professorDonald Preziosi

Donald Anthony Preziosi (born January 12, 1941) is an American art historian. He is Emeritus Professor of Art History at the University of California, Los Angeles. In August 2007, he became the MacGeorge Fellow at the University of Melbourne. He ...

, the panopticon prison of Bentham resonates with the ''memory theatre'' of Giulio Camillo

Giulio "Delminio" Camillo (ca. 1480–1544) was an Italian philosopher. He is best known for his ''Theatre of Memory'', described in his posthumously published work ''L’Idea del Theatro''.

Biography

Camillo was born around 1480 in Friuli, now ...

, where the sitting observer is at the centre and the phenomena are categorised in an array

An array is a systematic arrangement of similar objects, usually in rows and columns.

Things called an array include:

{{TOC right

Music

* In twelve-tone and serial composition, the presentation of simultaneous twelve-tone sets such that the ...

, which makes comparison, distinction, contrast and variation legible. Among the architectural references Bentham quoted for his panopticon prison was Ranelagh Gardens

Ranelagh Gardens (; alternative spellings include Ranelegh and Ranleigh, the latter reflecting the English pronunciation) were public pleasure gardens located in Chelsea, then just outside London, England, in the 18th century.

History

The R ...

, a London pleasure garden

A pleasure garden is a park or garden that is open to the public for recreation and entertainment. Pleasure gardens differ from other public gardens by serving as venues for entertainment, variously featuring such attractions as concert halls ...

with a dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

built around 1742. At the center of the rotunda beneath the dome was an elevated platform from which a 360 degrees

A circle is a shape consisting of all points in a plane that are at a given distance from a given point, the centre. Equivalently, it is the curve traced out by a point that moves in a plane so that its distance from a given point is cons ...

panorama

A panorama (formed from Greek πᾶν "all" + ὅραμα "view") is any wide-angle view or representation of a physical space, whether in painting, drawing, photography, film, seismic images, or 3D modeling. The word was originally coined i ...

could be viewed, illuminated through skylight

A skylight (sometimes called a rooflight) is a light-permitting structure or window, usually made of transparent or translucent glass, that forms all or part of the roof space of a building for daylighting and ventilation purposes.

History

Open ...

s. Professor Nicholas Mirzoeff compares the panopticon with the 19th-century diorama

A diorama is a replica of a scene, typically a three-dimensional full-size or miniature model, sometimes enclosed in a glass showcase for a museum. Dioramas are often built by hobbyists as part of related hobbies such as military vehicle mode ...

, because the architecture is arranged so that the ''seer'' views cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

or galleries.

In 1854 the work on the building that was to house the Royal Panopticon of Science and Art in

In 1854 the work on the building that was to house the Royal Panopticon of Science and Art in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

was completed. The rotunda at the centre of the building was encircled with a 91 meter procession. The interior reflected the taste for religiously meaningless ornament and emerged out of the contemporary taste for recreational learning. Visitors of the Royal Panopticon of Science and Art could view changing exhibits, including vacuum flasks, a pin making machine

A machine is a physical system using power to apply forces and control movement to perform an action. The term is commonly applied to artificial devices, such as those employing engines or motors, but also to natural biological macromolecul ...

, and a cook stove. However, a competitive entertainment industry

Entertainment is a form of activity that holds the attention and interest of an audience or gives pleasure and delight. It can be an idea or a task, but is more likely to be one of the activities or events that have developed over thousan ...

emerged in London and despite the varying music, the large fountains, interesting experiments, and opportunities for shopping

Shopping is an activity in which a customer browses the available goods or services presented by one or more retailers with the potential intent to purchase a suitable selection of them. A typology of shopper types has been developed by scho ...

, two years after opening the amateur science panopticon project closed.

Panopticon principle lies as the central idea in the plot of '' We'' (), a dystopian novel by Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin

Yevgeny Ivanovich Zamyatin ( rus, Евге́ний Ива́нович Замя́тин, p=jɪvˈɡʲenʲɪj ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ zɐˈmʲætʲɪn; – 10 March 1937), sometimes anglicized as Eugene Zamyatin, was a Russian author of science fictio ...

, written 1920–1921. Zamyatin goes beyond a concept of a single prison and projects panopticon principles to the whole society where people live in buildings with fully transparent walls.

Foucault's theories positioned Bentham's panopticon prison in the social structures of 1970s Europe. This led to the widespread use of the panopticon in literature, comic books, computer games, and TV series. In ''Doctor Who

''Doctor Who'' is a British science fiction television series broadcast by the BBC since 1963. The series depicts the adventures of a Time Lord called the Doctor, an extraterrestrial being who appears to be human. The Doctor explores the ...

,'' an abandoned panopticon was featured. In the 1981 the novella ''Chronicle of a Death Foretold

''Chronicle of a Death Foretold'' ( es, Crónica de una muerte anunciada) is a novella by Gabriel García Márquez, published in 1981. It tells, in the form of a pseudo- journalistic reconstruction, the story of the murder of Santiago Nasar by ...

'' by Gabriel García Márquez

Gabriel José de la Concordia García Márquez (; 6 March 1927 – 17 April 2014) was a Colombian novelist, short-story writer, screenwriter, and journalist, known affectionately as Gabo () or Gabito () throughout Latin America. Considered one ...

on the murder of Santiago Nasar, chapter four is written with a view on the characters through the panopticon of Riohacha

Riohacha (; Wayuu: ) is a city in the Riohacha Municipality in the northern Caribbean Region of Colombia by the mouth of the Ranchería River and the Caribbean Sea. It is the capital city of the La Guajira Department. It has a sandy beach waterfr ...

. Angela Carter

Angela Olive Pearce (formerly Carter, Stalker; 7 May 1940 – 16 February 1992), who published under the name Angela Carter, was an English novelist, short story writer, poet, and journalist, known for her feminist, magical realism, and picar ...

, in her 1984 novel'' Nights at the Circus,'' linked the panopticon of ''Countes P'' to a "perverse honeycomb" and made the character the matriarchal

Matriarchy is a social system in which women hold the primary power positions in roles of authority. In a broader sense it can also extend to moral authority, social privilege and control of property.

While those definitions apply in general En ...

queen bee

A queen bee is typically an adult, mated female ( gyne) that lives in a colony or hive of honey bees. With fully developed reproductive organs, the queen is usually the mother of most, if not all, of the bees in the beehive. Queens are developed ...

. In the 2011 TV series

A television show – or simply TV show – is any content produced for viewing on a television set which can be broadcast via over-the-air, satellite, or cable, excluding breaking news, advertisements, or trailers that are typically placed b ...

, ''Person of Interest

"Person of interest" is a term used by law enforcement in the United States, Canada, and other countries when identifying someone possibly involved in a criminal investigation who has not been arrested or formally accused of a crime. It has no le ...

'', Foucault's panopticon is used to grasp the pressure under which the character Harold Finch

Sir Harold Josiah Finch (2 May 189816 July 1979) was a Welsh Labour Party politician born in Barry, Glamorgan. He was a miners' agent in Blackwood after the First World War, Finch was a contemporary of Aneurin Bevan and accompanied him a ...

suffers in the post-9/11

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commerci ...

United States of America. In the manga series '' Usogui'' by author Sako Toshio, an abandoned panopticon is the main setting of the Air Poker arc.

See also

*Atrium (architecture)

In architecture, an atrium (plural: atria or atriums) is a large open-air or skylight-covered space surrounded by a building.

Atria were a common feature in Ancient Roman dwellings, providing light and ventilation to the interior. Modern atr ...

* Architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings ...

* Consumerism

Consumerism is a social and economic order that encourages the acquisition of goods and services in ever-increasing amounts. With the Industrial Revolution, but particularly in the 20th century, mass production led to overproduction—the su ...

* Landscapes of power

* Mass surveillance

Mass surveillance is the intricate surveillance of an entire or a substantial fraction of a population in order to monitor that group of citizens. The surveillance is often carried out by local and federal governments or governmental organizati ...

* PRISM (surveillance program)

Prism usually refers to:

* Prism (optics), a transparent optical component with flat surfaces that refract light

* Prism (geometry), a kind of polyhedron

Prism may also refer to:

Science and mathematics

* Prism (geology), a type of sedimentary ...

* Right to privacy

The right to privacy is an element of various legal traditions that intends to restrain governmental and private actions that threaten the privacy of individuals. Over 150 national constitutions mention the right to privacy. On 10 December 194 ...

* Social facilitation

Social facilitation is a social phenomenon in which being in the presence of others improves individual task performance. That is, people do better on tasks when they are with other people rather than when they are doing the task alone. Situation ...

* Sousveillance

Sousveillance ( ) is the recording of an activity by a member of the public, rather than a person or organisation in authority, typically by way of small wearable or portable personal technologies. The term, coined by Steve Mann, stems from th ...

* Urban planning

Urban planning, also known as town planning, city planning, regional planning, or rural planning, is a technical and political process that is focused on the development and design of land use and the built environment, including air, water, ...

* Total institution

* Torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts ...

References

{{Online social networking 18th-century philosophy Jeremy Bentham Prisons Surveillance