Paleoanthropological Sites on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Paleoanthropology or paleo-anthropology is a branch of

The science arguably began in the late 19th century when important discoveries occurred that led to the study of human evolution. The discovery of the

The science arguably began in the late 19th century when important discoveries occurred that led to the study of human evolution. The discovery of the

Prior to the general acceptance of Africa as the root of genus ''Homo'', 19th-century naturalists sought the origin of humans in Asia. So-called "dragon bones" (fossil bones and teeth) from Chinese apothecary shops were known, but it was not until the early 20th century that German paleontologist, Max Schlosser, first described a single human tooth from

Prior to the general acceptance of Africa as the root of genus ''Homo'', 19th-century naturalists sought the origin of humans in Asia. So-called "dragon bones" (fossil bones and teeth) from Chinese apothecary shops were known, but it was not until the early 20th century that German paleontologist, Max Schlosser, first described a single human tooth from  Excavations continued at the site and remained fruitful until the outbreak of the

Excavations continued at the site and remained fruitful until the outbreak of the

*

*

Paleoanthropology in the 1990s

– Essays b

Becoming Human: Paleoanthropology, Evolution and Human Origins

Department of Human Evolution ~ Max Planck Institute, Leipzig

Human Timeline (Interactive)

– Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016). {{Authority control Anthropology Biological anthropology

paleontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of foss ...

and anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

which seeks to understand the early development of anatomically modern human

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

s, a process known as hominization

Hominization, also called anthropogenesis, refers to the process of becoming human, and is used in somewhat different contexts in the fields of paleontology and paleoanthropology, archaeology, philosophy, and theology.

Paleontology

, paleoanthro ...

, through the reconstruction of evolutionary kinship

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says tha ...

lines within the family Hominidae

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the ...

, working from biological evidence (such as petrified

In geology, petrifaction or petrification () is the process by which organic material becomes a fossil through the replacement of the original material and the filling of the original pore spaces with minerals. Petrified wood typifies this proce ...

skeletal remains, bone fragments, footprints) and cultural evidence (such as stone tool

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone Ag ...

s, artifacts, and settlement localities).

The field draws from and combines primatology

Primatology is the scientific study of primates. It is a diverse discipline at the boundary between mammalogy and anthropology, and researchers can be found in academic departments of anatomy, anthropology, biology, medicine, psychology, vete ...

, paleontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of foss ...

, biological anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from an e ...

, and cultural anthropology

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans. It is in contrast to social anthropology, which perceives cultural variation as a subset of a posited anthropological constant. The portma ...

. As technologies and methods advance, genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

plays an ever-increasing role, in particular to examine and compare DNA structure as a vital tool of research of the evolutionary kinship lines of related species and genera.

Etymology

The term paleoanthropology derives from Greek palaiós (παλαιός) "old, ancient", ánthrōpos (ἄνθρωπος) "man, human" and the suffix -logía (-λογία) "study of".Hominoid taxonomies

Hominoids are a primate superfamily, the hominid family is currently considered to comprise both thegreat ape

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the ea ...

lineages and human lineages within the hominoid

Apes (collectively Hominoidea ) are a clade of Old World simians native to sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia (though they were more widespread in Africa, most of Asia, and as well as Europe in prehistory), which together with its sister ...

superfamily. The " Homininae" comprise both the human lineages and the African ape lineages. The term "African apes" refers only to chimpanzees and gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four ...

s. The terminology of the immediate biological family is currently in flux. The term "hominin" refers to any genus in the human tribe (Hominini), of which ''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, a ...

'' (modern humans) is the only living specimen.

History

18th century

In 1758Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his Nobility#Ennoblement, ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalise ...

introduced the name ''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, a ...

'' as a species name in the 10th edition of his work ''Systema Naturae

' (originally in Latin written ' with the ligature æ) is one of the major works of the Swedish botanist, zoologist and physician Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) and introduced the Linnaean taxonomy. Although the system, now known as binomial n ...

'' although without a scientific description of the species-specific characteristics. Since the great apes were considered the closest relatives of human beings, based on morphological similarity, in the 19th century, it was speculated that the closest living relatives to humans were chimpanzees (genus '' Pan'') and gorilla (genus ''Gorilla

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus ''Gorilla'' is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four ...

''), and based on the natural range of these creatures, it was surmised that humans shared a common ancestor with Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

n apes and that fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s of these ancestors would ultimately be found in Africa.

19th century

The science arguably began in the late 19th century when important discoveries occurred that led to the study of human evolution. The discovery of the

The science arguably began in the late 19th century when important discoveries occurred that led to the study of human evolution. The discovery of the Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While the ...

in Germany, Thomas Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The storie ...

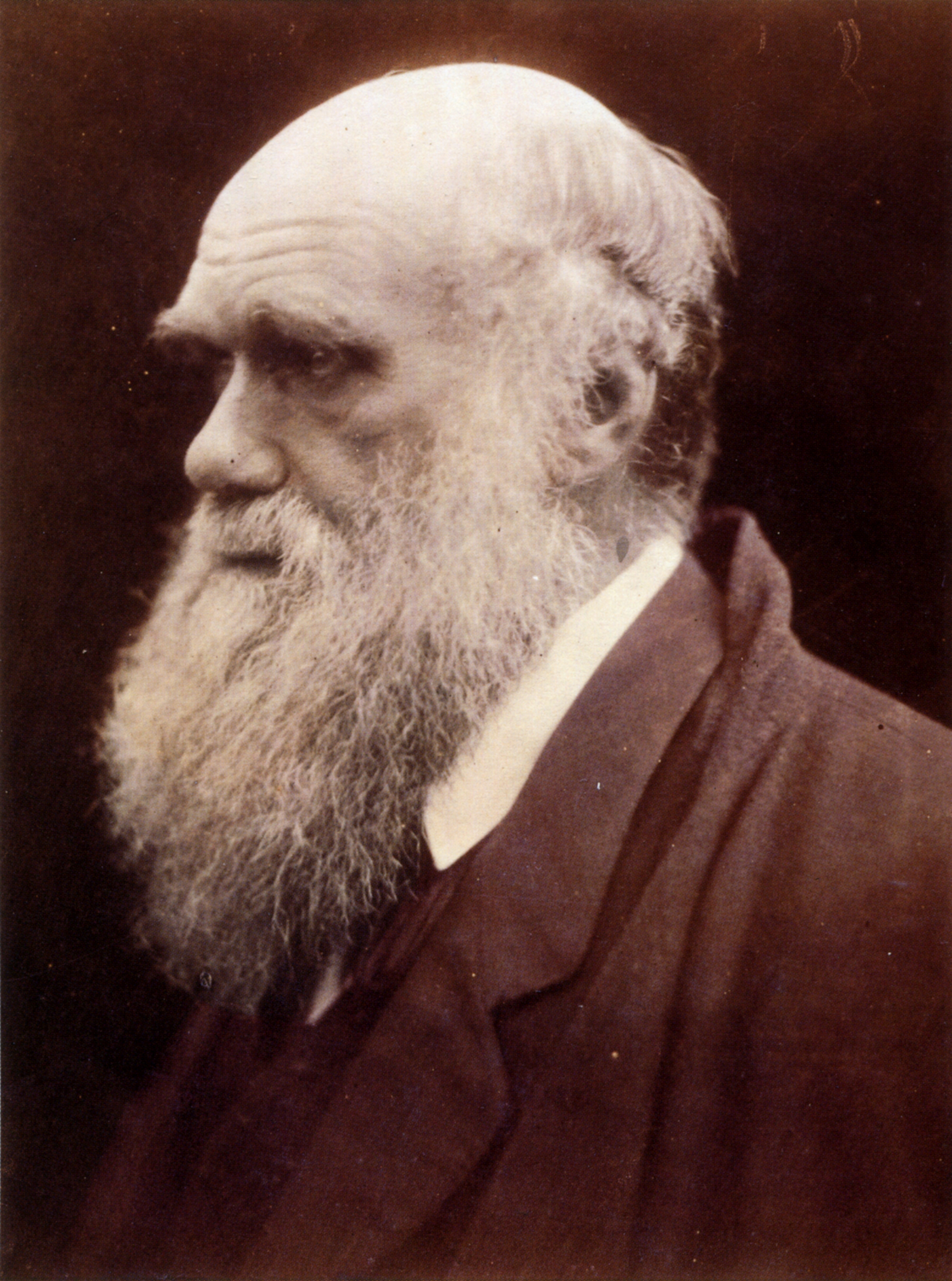

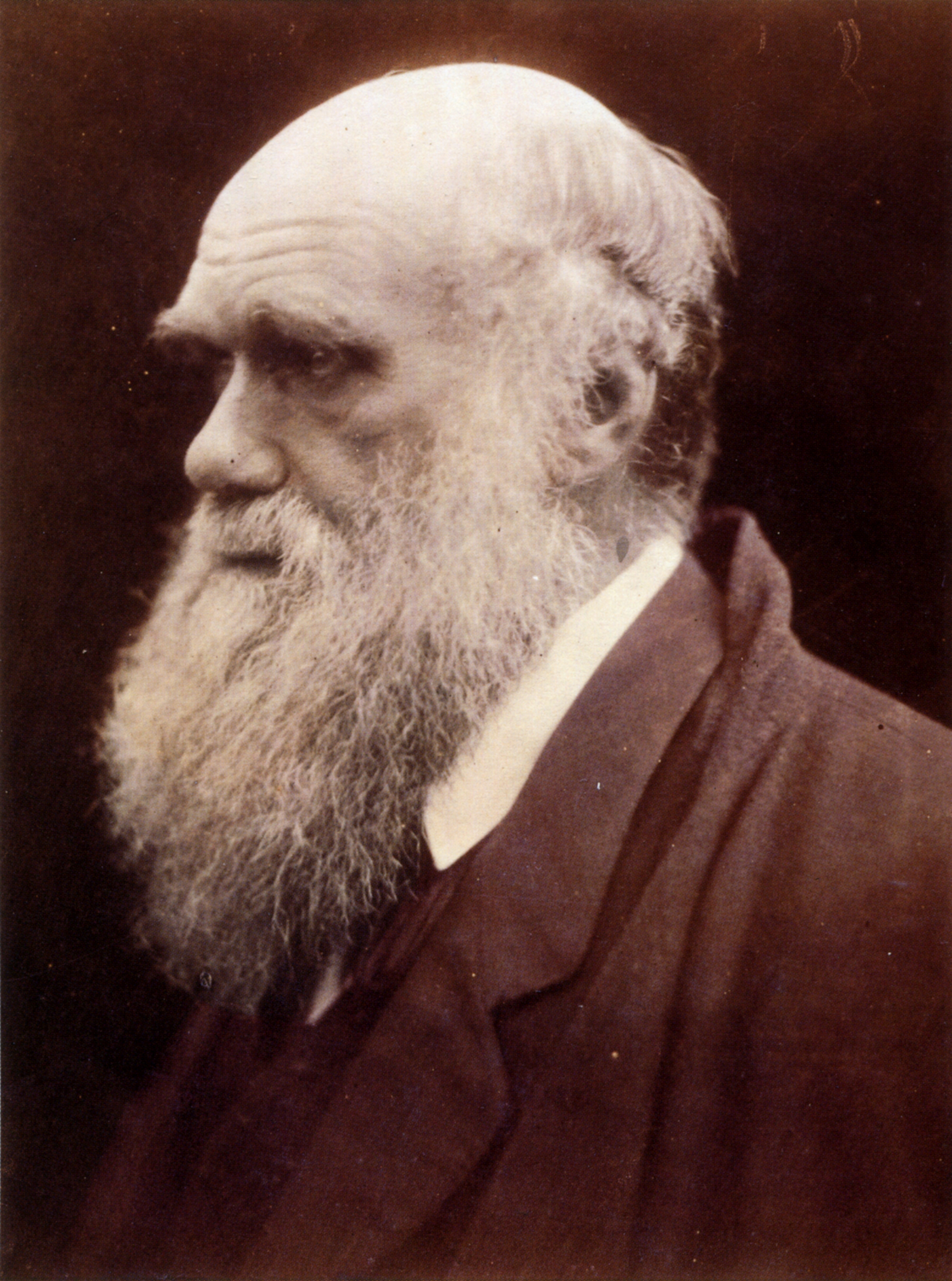

's '' Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature'', and Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended f ...

's ''The Descent of Man

''The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex'' is a book by English naturalist Charles Darwin, first published in 1871, which applies evolutionary theory to human evolution, and details his theory of sexual selection, a form of biolo ...

'' were both important to early paleoanthropological research.

The modern field of paleoanthropology began in the 19th century with the discovery of "Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While the ...

man" (the eponymous skeleton was found in 1856, but there had been finds elsewhere since 1830), and with evidence of so-called cave men. The idea that humans are similar to certain great ape

The Hominidae (), whose members are known as the great apes or hominids (), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: '' Pongo'' (the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan); ''Gorilla'' (the ea ...

s had been obvious to people for some time, but the idea of the biological evolution of species in general was not legitimized until after Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended f ...

published ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'' in 1859.

Though Darwin's first book on evolution did not address the specific question of human evolution—"light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history," was all Darwin wrote on the subject—the implications of evolutionary theory were clear to contemporary readers.

Debates between Thomas Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The storie ...

and Richard Owen focused on the idea of human evolution. Huxley convincingly illustrated many of the similarities and differences between humans and apes in his 1863 book '' Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature''. By the time Darwin published his own book on the subject, '' Descent of Man'', it was already a well-known interpretation of his theory—and the interpretation which made the theory highly controversial. Even many of Darwin's original supporters (such as Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution through natural s ...

and Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

) balked at the idea that human beings could have evolved their apparently boundless mental capacities and moral sensibilities through natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Char ...

.

Asia

Prior to the general acceptance of Africa as the root of genus ''Homo'', 19th-century naturalists sought the origin of humans in Asia. So-called "dragon bones" (fossil bones and teeth) from Chinese apothecary shops were known, but it was not until the early 20th century that German paleontologist, Max Schlosser, first described a single human tooth from

Prior to the general acceptance of Africa as the root of genus ''Homo'', 19th-century naturalists sought the origin of humans in Asia. So-called "dragon bones" (fossil bones and teeth) from Chinese apothecary shops were known, but it was not until the early 20th century that German paleontologist, Max Schlosser, first described a single human tooth from Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 2 ...

. Although Schlosser (1903) was very cautious, identifying the tooth only as "?''Anthropoide g. et sp. indet''?," he was hopeful that future work would discover a new anthropoid in China.

Eleven years later, the Swedish geologist Johan Gunnar Andersson

Johan Gunnar Andersson (3 July 1874 – 29 October 1960)"Andersson, Johan Gunnar" in '' The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th edn., 1992, Vol. 1, p. 385. was a Swedish archaeologist, paleontologist and ...

was sent to China as a mining advisor and soon developed an interest in "dragon bones". It was he who, in 1918, discovered the sites around Zhoukoudian

Zhoukoudian Area () is a town and an area located on the east Fangshan District, Beijing, China. It borders Nanjiao and Fozizhuang Townships to its north, Xiangyang, Chengguan and Yingfeng Subdistricts to its east, Shilou and Hangcunhe Towns to ...

, a village about 50 kilometers southwest of Beijing. However, because of the sparse nature of the initial finds, the site was abandoned.

Work did not resume until 1921, when the Austrian paleontologist, Otto Zdansky, fresh with his doctoral degree from Vienna, came to Beijing to work for Andersson. Zdansky conducted short-term excavations at Locality 1 in 1921 and 1923, and recovered only two teeth of significance (one premolar and one molar) that he subsequently described, cautiously, as "?''Homo sp.''" (Zdansky, 1927). With that done, Zdansky returned to Austria and suspended all fieldwork.

News of the fossil hominin teeth delighted the scientific community in Beijing, and plans for developing a larger, more systematic project at Zhoukoudian were soon formulated. At the epicenter of excitement was Davidson Black, a Canadian-born anatomist working at Peking Union Medical College

Peking Union Medical College (), founded in 1906, is a selective public medical college based in Dongcheng, Beijing, China. It is a Chinese Ministry of Education Double First Class University Plan university. The school is tied to the Peking U ...

. Black shared Andersson’s interest, as well as his view that central Asia was a promising home for early humankind. In late 1926, Black submitted a proposal to the Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, after the Ca ...

seeking financial support for systematic excavation at Zhoukoudian and the establishment of an institute for the study of human biology in China.

The Zhoukoudian Project came into existence in the spring of 1927, and two years later, the Cenozoic Research Laboratory of the Geological Survey of China was formally established. Being the first institution of its kind, the Cenozoic Laboratory opened up new avenues for the study of paleogeology and paleontology in China. The Laboratory was the precursor of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology The Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP; ) of China is a research institution and collections repository for fossils, including many dinosaur and pterosaur specimens (many from the Yixian Formation). As its name suggest ...

(IVPP) of the Chinese Academy of Science, which took its modern form after 1949.

The first of the major project finds are attributed to the young Swedish paleontologist, Anders Birger Bohlin, then serving as the field advisor at Zhoukoudian

Zhoukoudian Area () is a town and an area located on the east Fangshan District, Beijing, China. It borders Nanjiao and Fozizhuang Townships to its north, Xiangyang, Chengguan and Yingfeng Subdistricts to its east, Shilou and Hangcunhe Towns to ...

. He recovered a left lower molar that Black (1927) identified as unmistakably human (it compared favorably to the previous find made by Zdansky), and subsequently coined it '' Sinanthropus pekinensis''. The news was at first met with skepticism, and many scholars had reservations that a single tooth was sufficient to justify the naming of a new type of early hominin. Yet within a little more than two years, in the winter of 1929, Pei Wenzhong, then the field director at Zhoukoudian, unearthed the first complete calvaria of Peking Man. Twenty-seven years after Schlosser’s initial description, the antiquity of early humans in East Asia was no longer a speculation, but a reality.

Excavations continued at the site and remained fruitful until the outbreak of the

Excavations continued at the site and remained fruitful until the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese ...

in 1937. The decade-long research yielded a wealth of faunal and lithic materials, as well as hominin fossils. These included 5 more complete calvaria, 9 large cranial fragments, 6 facial fragments, 14 partial mandibles, 147 isolated teeth, and 11 postcranial elements—estimated to represent as least 40 individuals. Evidence of fire, marked by ash lenses and burned bones and stones, were apparently also present, although recent studies have challenged this view. Franz Weidenreich

Franz Weidenreich (7 June 1873 – 11 July 1948) was a Jewish German anatomist and physical anthropologist who studied evolution.

Life and career

Weidenreich studied at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Universität in Strasbourg where he earned a medica ...

came to Beijing soon after Black’s untimely death in 1934, and took charge of the study of the hominin specimens.

Following the loss of the Peking Man materials in late 1941, scientific endeavors at Zhoukoudian slowed, primarily because of lack of funding. Frantic search for the missing fossils took place, and continued well into the 1950s. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

in 1949, excavations resumed at Zhoukoudian. But with political instability and social unrest brewing in China, beginning in 1966, and major discoveries at Olduvai Gorge

The Olduvai Gorge or Oldupai Gorge in Tanzania is one of the most important paleoanthropological localities in the world; the many sites exposed by the gorge have proven invaluable in furthering understanding of early human evolution. A steep- ...

and East Turkana (Koobi Fora

Koobi Fora refers primarily to a region around Koobi Fora Ridge, located on the eastern shore of Lake Turkana in the territory of the nomadic Gabbra people. According to the National Museums of Kenya, the name comes from the Gabbra language:

...

), the paleoanthropological spotlight shifted westward to East Africa. Although China re-opened its doors to the West in the late 1970s, national policy calling for self-reliance, coupled with a widened language barrier, thwarted all the possibilities of renewed scientific relationships. Indeed, Harvard anthropologist K. C. Chang noted, "international collaboration (in developing nations very often a disguise for Western domination) became a thing of the past" (1977: 139).

Africa

1920s – 1940s

The first paleoanthropological find made in Africa was the 1921 discovery of the Kabwe 1 skull at Kabwe (Broken Hill), Zambia. Initially, this specimen was named '' Homo rhodesiensis''; however, today it is considered part of the species ''Homo heidelbergensis

''Homo heidelbergensis'' (also ''H. sapiens heidelbergensis''), sometimes called Heidelbergs, is an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human which existed during the Middle Pleistocene. It was subsumed as a subspecies of '' H. erectus'' i ...

''.

In 1924 in a limestone quarry at Taung

Taung is a small town situated in the North West Province of South Africa. The name means ''place of the lion'' and was named after Tau, the King of the Barolong. ''Tau'' is the Tswana word for lion.

Education

High,Secondary and Middle Schools ...

, Professor Raymond Dart discovered a remarkably well-preserved juvenile specimen (face and brain endocast), which he named '' Australopithecus africanus'' (''Australopithecus'' meaning "Southern Ape"). Although the brain was small (410 cm³), its shape was rounded, unlike the brain shape of chimpanzees and gorillas, and more like the shape seen in modern humans. In addition, the specimen exhibited short canine teeth

In mammalian oral anatomy, the canine teeth, also called cuspids, dog teeth, or (in the context of the upper jaw) fangs, eye teeth, vampire teeth, or vampire fangs, are the relatively long, pointed teeth. They can appear more flattened however, ...

, and the anterior placement of the foramen magnum was more like the placement seen in modern humans than the placement seen in chimpanzees and gorillas, suggesting that this species was bipedal.

All of these traits convinced Dart that the Taung child was a bipedal human ancestor, a transitional form between ape and human. However, Dart's conclusions were largely ignored for decades, as the prevailing view of the time was that a large brain evolved before bipedality. It took the discovery of additional australopith fossils in Africa that resembled his specimen, and the rejection of the Piltdown Man hoax, for Dart's claims to be taken seriously.

In the 1930s, paleontologist Robert Broom

Robert Broom FRS FRSE (30 November 1866 6 April 1951) was a British- South African doctor and palaeontologist. He qualified as a medical practitioner in 1895 and received his DSc in 1905 from the University of Glasgow.

From 1903 to 1910, h ...

discovered and described a new species at Kromdraai

Kromdraai Conservancy is a protected conservation park located to the south-west of Gauteng province in north-east South Africa. It is in the Muldersdrift area not far from Krugersdorp.

Etymology

Its name is derived from Afrikaans meaning "Cr ...

, South Africa. Although similar in some ways to Dart's ''Australopithecus africanus'', Broom's specimen had much larger cheek teeth. Because of this difference, Broom named his specimen ''Paranthropus robustus

''Paranthropus robustus'' is a species of robust australopithecine from the Early and possibly Middle Pleistocene of the Cradle of Humankind, South Africa, about 2.27 to 0.87 (or, more conservatively, 2 to 1) million years ago. It has been i ...

'', using a new genus name. In doing so, he established the practice of grouping gracile australopiths in the genus ''Australopithecus'' and robust australopiths in the genus ''Paranthropus

''Paranthropus'' is a genus of extinct hominin which contains two widely accepted species: '' P. robustus'' and '' P. boisei''. However, the validity of ''Paranthropus'' is contested, and it is sometimes considered to be synonymous with ''Aust ...

.'' During the 1960s, the robust variety was commonly moved into ''Australopithecus''. A more recent consensus has been to return to the original classification of ''Paranthropus'' as a separate genus.

1950s – 1990s

The second half of the twentieth century saw a significant increase in the number of paleoanthropological finds made in Africa. Many of these finds were associated with the work of the Leakey family in eastern Africa. In 1959,Mary Leakey

Mary Douglas Leakey, FBA (née Nicol, 6 February 1913 – 9 December 1996) was a British paleoanthropologist who discovered the first fossilised ''Proconsul'' skull, an extinct ape which is now believed to be ancestral to humans. She also disc ...

's discovery of the Zinj fossin ( OH 5) at Olduvai Gorge

The Olduvai Gorge or Oldupai Gorge in Tanzania is one of the most important paleoanthropological localities in the world; the many sites exposed by the gorge have proven invaluable in furthering understanding of early human evolution. A steep- ...

, Tanzania, led to the identification of a new species, ''Paranthropus boisei

''Paranthropus boisei'' is a species of australopithecine from the Early Pleistocene of East Africa about 2.5 to 1.15 million years ago. The holotype specimen, OH 5, was discovered by palaeoanthropologist Mary Leakey in 1959, and described b ...

''. In 1960, the Leakeys discovered the fossil OH 7, also at Olduvai Gorge, and assigned it to a new species, ''Homo habilis

''Homo habilis'' ("handy man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East and South Africa about 2.31 million years ago to 1.65 million years ago (mya). Upon species description in 1964, ''H. habilis'' was highly c ...

''. In 1972, Bernard Ngeneo, a fieldworker working for Richard Leakey, discovered the fossil KNM-ER 1470 near Lake Turkana

Lake Turkana (), formerly known as Lake Rudolf, is a lake in the Kenyan Rift Valley, in northern Kenya, with its far northern end crossing into Ethiopia. It is the world's largest permanent desert lake and the world's largest alkaline lake. B ...

in Kenya. KNM-ER 1470 has been interpreted as either a distinct species, '' Homo rudolfensis'', or alternatively as evidence of sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most an ...

in ''Homo habilis

''Homo habilis'' ("handy man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East and South Africa about 2.31 million years ago to 1.65 million years ago (mya). Upon species description in 1964, ''H. habilis'' was highly c ...

''. In 1967, Richard Leakey reported the earliest definitive examples of anatomically modern ''Homo sapiens'' from the site of Omo Kibish in Ethiopia, known as the Omo remains

The Omo remains are a collection of homininThis article quotes historic texts that use the terms 'hominid' and 'hominin' with meanings that may be different from their modern usages. This is because several revisions in classifying the great apes h ...

. In the late 1970s, Mary Leakey excavated the famous Laetoli footprints

Laetoli is a pre-historic site located in Enduleni ward of Ngorongoro District in Arusha Region, Tanzania. The site is dated to the Plio-Pleistocene and famous for its Hominina footprints, preserved in volcanic ash. The site of the Laetoli ...

in Tanzania, which demonstrated the antiquity of bipedality in the human lineage. In 1985, Richard Leakey and Alan Walker discovered a specimen they called the Black Skull, found near Lake Turkana. This specimen was assigned to another species, '' Paranthropus aethiopicus''. In 1994, a team led by Meave Leakey

Meave G. Leakey (born Meave Epps; 28 July 1942) is a British palaeoanthropologist. She works at Stony Brook University and is co-ordinator of Plio-Pleistocene research at the Turkana Basin Institute. She studies early hominid evolution and has ...

announced a new species, ''Australopithecus anamensis

''Australopithecus anamensis'' is a hominin species that lived approximately between 4.2 and 3.8 million years ago and is the oldest known ''Australopithecus'' species, living during the Plio-Pleistocene era.

Nearly one hundred fossil specimens ...

'', based on specimens found near Lake Turkana.

Numerous other researchers have made important discoveries in eastern Africa. Possibly the most famous is the Lucy skeleton, discovered in 1973 by Donald Johanson

Donald Carl Johanson (born June 28, 1943) is an American paleoanthropologist. He is known for discovering, with Yves Coppens and Maurice Taieb, the fossil of a female hominin australopithecine known as " Lucy" in the Afar Triangle region of H ...

and Maurice Taieb

Maurice Taieb (22 July 1935 – 23 July 2021) was a French geologist and paleoanthropologist. He discovered the Hadar formation, recognized its potential importance to paleoanthropology and founded the International Afar Research Expedition (IAR ...

in Ethiopia's Afar Triangle

The Afar Triangle (also called the Afar Depression) is a geological depression caused by the Afar Triple Junction, which is part of the Great Rift Valley in East Africa. The region has disclosed fossil specimens of the very earliest hominins; ...

at the site of Hadar. On the basis of this skeleton and subsequent discoveries, the researchers came up with a new species, ''Australopithecus afarensis

''Australopithecus afarensis'' is an extinct species of australopithecine which lived from about 3.9–2.9 million years ago (mya) in the Pliocene of East Africa. The first fossils were discovered in the 1930s, but major fossil finds would not ta ...

''. In 1975, Colin Groves and Vratislav Mazák announced a new species of human they called '' Homo ergaster''. ''Homo ergaster'' specimens have been found at numerous sites in eastern and southern Africa. In 1994, Tim D. White announced a new species, '' Ardipithecus ramidus'', based on fossils from Ethiopia.

In 1999, two new species were announced. Berhane Asfaw

Berhane Asfaw (Amharic: በርሃነ አስፋው) (born August 22, 1954 in Gondar, Ethiopia) is an Ethiopian paleontologist of Rift Valley Research Service, who co-discovered human skeletal remains at Herto Bouri, Ethiopia later classified as ...

and Tim D. White named '' Australopithecus garhi'' based on specimens discovered in Ethiopia's Awash valley. Meave Leakey announced a new species, '' Kenyanthropus platyops'', based on the cranium KNM-WT 40000 from Lake Turkana.

21st century

In the 21st century, numerous fossils have been found that add to current knowledge of existing species. For example, in 2001, Zeresenay Alemseged discovered an ''Australopithecus afarensis'' child fossil, called Selam, from the site of Dikika in the Afar region of Ethiopia. This find is particularly important because the fossil included a preservedhyoid bone

The hyoid bone (lingual bone or tongue-bone) () is a horseshoe-shaped bone situated in the anterior midline of the neck between the chin and the thyroid cartilage. At rest, it lies between the base of the mandible and the third cervical ver ...

, something rarely found in other paleoanthropological fossils but important for understanding the evolution of speech capacities.

Two new species from southern Africa have been discovered and described in recent years. In 2008, a team led by Lee Berger announced a new species, ''Australopithecus sediba

''Australopithecus sediba'' is an extinct species of australopithecine recovered from Malapa Cave, Cradle of Humankind, South Africa. It is known from a partial juvenile skeleton, the holotype MH1, and a partial adult female skeleton, the par ...

'', based on fossils they had discovered in Malapa cave in South Africa. In 2015, a team also led by Lee Berger announced another species, ''Homo naledi

'' Homo naledi'' is an extinct species of archaic human discovered in 2013 in the Rising Star Cave, Cradle of Humankind, South Africa dating to the Middle Pleistocene 335,000–236,000 years ago. The initial discovery comprises 1,550 specime ...

'', based on fossils representing 15 individuals from the Rising Star Cave system in South Africa.

New species have also been found in eastern Africa. In 2000, Brigitte Senut and Martin Pickford described the species '' Orrorin tugenensis'', based on fossils they found in Kenya. In 2004, Yohannes Haile-Selassie announced that some specimens previously labeled as ''Ardipithecus ramidus'' made up a different species, '' Ardipithecus kadabba''. In 2015, Haile-Selassie announced another new species, '' Australopithecus deyiremeda'', though some scholars are skeptical that the associated fossils truly represent a unique species.

Although most hominin fossils from Africa have been found in eastern and southern Africa, there are a few exceptions. One is '' Sahelanthropus tchadensis'', discovered in the central African country of Chad in 2002. This find is important because it widens the assumed geographic range of early hominins.

Renowned paleoanthropologists

*

* Robert Ardrey

Robert Ardrey (October 16, 1908 – January 14, 1980) was an American playwright, screenwriter and science writer perhaps best known for '' The Territorial Imperative'' (1966). After a Broadway and Hollywood career, he returned to his academic t ...

(1908–1980)

* Lee Berger (1965–)

* Davidson Black (1884–1934)

* Robert Broom

Robert Broom FRS FRSE (30 November 1866 6 April 1951) was a British- South African doctor and palaeontologist. He qualified as a medical practitioner in 1895 and received his DSc in 1905 from the University of Glasgow.

From 1903 to 1910, h ...

(1866–1951)

* Michel Brunet (1940–)

* J. Desmond Clark (1916–2002)

* Carleton S. Coon

Carleton Stevens Coon (June 23, 1904 – June 3, 1981) was an American anthropologist. A professor of anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, lecturer and professor at Harvard University, he was president of the American Association ...

(1904–1981)

* Raymond Dart (1893–1988)

* Eugene Dubois (1858–1940)

* Johann Carl Fuhlrott

Prof. Dr. Johann Carl Fuhlrott (31 December 1803, Leinefelde, Germany – 17 October 1877, Wuppertal) was an early German paleoanthropologist. He is famous for recognizing the significance of the bones of Neanderthal 1, a Neanderthal specimen di ...

(1803–1877)

* Aleš Hrdlička

Alois Ferdinand Hrdlička, after 1918 changed to Aleš Hrdlička (; March 30,HRDLICKA, ALES ...

(1869–1943)

* Glynn Isaac (1937–1985)

* Donald C. Johanson (1943–)

* Kamoya Kimeu

Kamoya Kimeu (1938 – 20 July 2022) was a Kenyan paleontologist and curator, whose contributions to the field of paleoanthropology were recognised with the National Geographic Society's LaGorce Medal and with an honorary doctorate of science deg ...

(1940–)

* Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald

Gustav Heinrich Ralph (often cited as G. H. R.) von Koenigswald (13 November 1902 – 10 July 1982) was a German-Dutch paleontologist and geologist who conducted research on hominins, including ''Homo erectus''. His discoverie ...

(1902–1982)

* Jeffrey Laitman (1951–)

* Louis Leakey

Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey (7 August 1903 – 1 October 1972) was a Kenyan-British palaeoanthropologist and archaeologist whose work was important in demonstrating that humans evolved in Africa, particularly through discoveries made at Olduvai ...

(1903–1972)

* Meave Leakey

Meave G. Leakey (born Meave Epps; 28 July 1942) is a British palaeoanthropologist. She works at Stony Brook University and is co-ordinator of Plio-Pleistocene research at the Turkana Basin Institute. She studies early hominid evolution and has ...

(1942–)

* Mary Leakey

Mary Douglas Leakey, FBA (née Nicol, 6 February 1913 – 9 December 1996) was a British paleoanthropologist who discovered the first fossilised ''Proconsul'' skull, an extinct ape which is now believed to be ancestral to humans. She also disc ...

(1913–1996)

* Richard Leakey (1944–2022)

* André Leroi-Gourhan

André Leroi-Gourhan (; ; 25 August 1911 – 19 February 1986) was a French archaeologist, paleontologist, paleoanthropologist, and anthropologist with an interest in technology and aesthetics and a penchant for philosophical reflection.

Bi ...

(1911–1986)

* Kenneth Oakley (1911–1981)

* David Pilbeam (1940–)

* John T. Robinson (1923–2001)

* Jeffrey H. Schwartz (1948–)

* Chris Stringer

Christopher Brian Stringer (born 1947) is a British physical anthropologist noted for his work on human evolution.

Biography

Growing up in a working-class family in the East End of London, Stringer's interest in anthropology began in primar ...

(1947–)

* Ian Tattersall (1945–)

* Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin ( (); 1 May 1881 – 10 April 1955) was a French Jesuit priest, scientist, paleontologist, theologian, philosopher and teacher. He was Darwinian in outlook and the author of several influential theological and philos ...

(1881–1955)

* Phillip V. Tobias (1925–2012)

* Erik Trinkaus (1948–)

* Alan Walker

Alan Olav Walker (born 24 August 1997) is a British-born Norwegian music producer and DJ primarily known for the critically acclaimed single " Faded" (2015), which was certified platinum in 14 countries. He has also made several songs including ...

(1938–2017)

* Franz Weidenreich

Franz Weidenreich (7 June 1873 – 11 July 1948) was a Jewish German anatomist and physical anthropologist who studied evolution.

Life and career

Weidenreich studied at the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Universität in Strasbourg where he earned a medica ...

(1873–1948)

* Milford H. Wolpoff (1942–)

* Tim D. White (1950–)

* John D. Hawks

John Hawks is an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He also maintains a paleoanthropology blog. Contrary to the common view that cultural evolution has made human biological evolution insignificant, ...

* Yohannes Haile-Selassie (1961–)

* Sonia Harmand (1974–)

* Bernard Wood (1945–)

See also

* ''Dawn of Humanity'' (2015 PBS film) * Human evolution * List of human evolution fossils * The Incredible Human Journey * Timeline of human evolutionReferences

Further reading

* David R. Begun, ''A Companion to Paleoanthropology'', Malden, Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. * Winfried Henke, Ian Tattersall (eds.), ''Handbook of Paleoanthropology'', Dordrecht, Springer, 2007.External links

Paleoanthropology in the 1990s

– Essays b

Becoming Human: Paleoanthropology, Evolution and Human Origins

Department of Human Evolution ~ Max Planck Institute, Leipzig

Human Timeline (Interactive)

– Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016). {{Authority control Anthropology Biological anthropology