Pursuit Of Goeben And Breslau on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The pursuit of ''Goeben'' and ''Breslau'' was a naval action that occurred in the

Meanwhile, on 30 July

Meanwhile, on 30 July

Without specific orders, Souchon had decided to position his ships off the coast of

Without specific orders, Souchon had decided to position his ships off the coast of

The rated speed of ''Goeben'' was , but her damaged boilers meant she could only manage , and this was only achieved by working men and machinery to the limit; four stokers were killed by scalding

The rated speed of ''Goeben'' was , but her damaged boilers meant she could only manage , and this was only achieved by working men and machinery to the limit; four stokers were killed by scalding

Milne ordered ''Gloucester'' to disengage, still expecting Souchon to turn west, but it was apparent to ''Gloucester''′s captain that ''Goeben'' was fleeing. ''Breslau'' attempted to harass ''Gloucester'' into breaking off—Souchon had a collier waiting off the coast of

Milne ordered ''Gloucester'' to disengage, still expecting Souchon to turn west, but it was apparent to ''Gloucester''′s captain that ''Goeben'' was fleeing. ''Breslau'' attempted to harass ''Gloucester'' into breaking off—Souchon had a collier waiting off the coast of

Superior Force: The Conspiracy Behind the Escape of ''Goeben'' and ''Breslau''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Goeben And Breslau Mediterranean naval operations of World War I Naval battles of World War I involving France Naval battles of World War I involving Germany Naval battles of World War I involving the United Kingdom Naval battles of World War I involving Russia Naval battles of World War I involving the Ottoman Empire Conflicts in 1914 1914 in the Ottoman Empire July 1914 events August 1914 events

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

at the outbreak of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

when elements of the British Mediterranean Fleet attempted to intercept the German '' Mittelmeerdivision'' consisting of the battlecruiser and the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

. The German ships evaded the British fleet and passed through the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

to reach Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, where they were eventually handed over to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. Renamed ''Yavuz Sultan Selim'' and ''Midilli'', the former ''Goeben'' and ''Breslau'' were ordered by their German commander to attack Russian positions, in doing so bringing the Ottoman Empire into the war on the side of the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

.

Though a bloodless "battle," the failure of the British pursuit had enormous political and military ramifications. In the short term it effectively ended the careers of the two British Admirals who had been in charge of the pursuit. Writing several years later, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

—who had been First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

—expressed the opinion that by forcing Turkey into the war the ''Goeben'' had brought "more slaughter, more misery, and more ruin than has ever before been borne within the compass of a ship."

Prelude

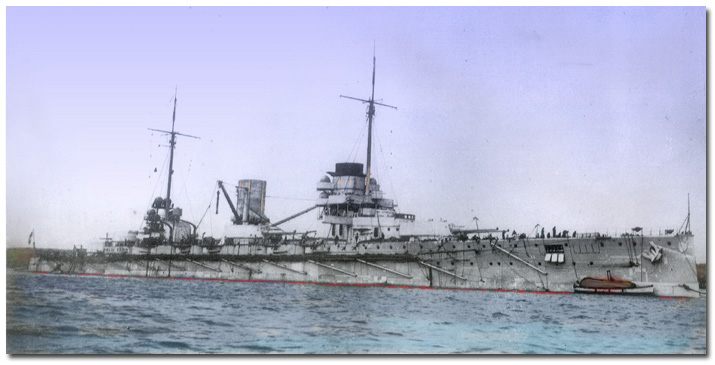

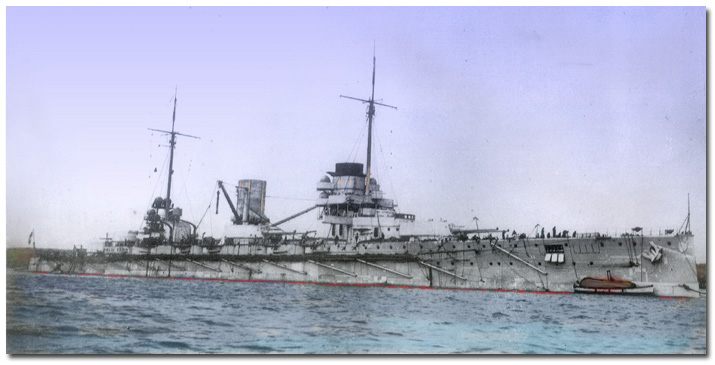

Dispatched in 1912, the ''Mittelmeerdivision'' of the ''Kaiserliche Marine

{{italic title

The adjective ''kaiserlich'' means "imperial" and was used in the German-speaking countries to refer to those institutions and establishments over which the ''Kaiser'' ("emperor") had immediate personal power of control.

The term wa ...

'' (Imperial Navy), comprising only the ''Goeben'' and ''Breslau'', was under the command of ''Konteradmiral

''Konteradmiral'', abbreviated KAdm or KADM, is the second lowest naval flag officer rank in the German Navy. It is equivalent to '' Generalmajor'' in the '' Heer'' and ''Luftwaffe'' or to '' Admiralstabsarzt'' and ''Generalstabsarzt'' in the '' ...

'' Wilhelm Souchon

Wilhelm Anton Souchon (; 2 June 1864 – 13 January 1946) was a German admiral in World War I. Souchon commanded the ''Kaiserliche Marine''s Mediterranean squadron in the early days of the war. His initiatives played a major part in the entry o ...

. In the event of war, the squadron's role was to intercept French transports bringing colonial troops from Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

to France.

When war broke out between Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

and Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

on 28 July 1914, Souchon was at Pola Pola or POLA may refer to:

People

* House of Pola, an Italian noble family

* Pola Alonso (1923–2004), Argentine actress

* Pola Brändle (born 1980), German artist and photographer

* Pola Gauguin (1883–1961), Danish painter

* Pola Gojawiczyńsk ...

in the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) ...

where ''Goeben'' was undergoing repairs to her boiler

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, centr ...

s. Not wishing to be trapped in the Adriatic, Souchon rushed to finish as much work as possible, but then took his ships out into the Mediterranean before all repairs were completed. He reached Brindisi

Brindisi ( , ) ; la, Brundisium; grc, Βρεντέσιον, translit=Brentésion; cms, Brunda), group=pron is a city in the region of Apulia in southern Italy, the capital of the province of Brindisi, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea.

Histo ...

on 1 August, but Italian port authorities made excuses to avoid coaling the ship. This was because Italy, despite being a co-signatory to the Triple Alliance, had decided to remain neutral. ''Goeben'' was joined by ''Breslau'' at Taranto

Taranto (, also ; ; nap, label= Tarantino, Tarde; Latin: Tarentum; Old Italian: ''Tarento''; Ancient Greek: Τάρᾱς) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto, serving as an important com ...

and the small squadron sailed for Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 inhabitants in ...

where Souchon was able to obtain of coal from German merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are u ...

s.

Meanwhile, on 30 July

Meanwhile, on 30 July Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, then the First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

, had instructed the commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Sir Archibald Berkeley Milne, to cover the French transports taking the XIX Corps from North Africa across the Mediterranean to France. The Mediterranean British Fleet—based at Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

—comprised three fast, modern battlecruisers (, , and ), as well as four armoured cruisers, four light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

s and a flotilla of 14 destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s.

Milne's instructions were "to aid the French in the transportation of their African Army by covering, and if possible, bringing to action individual fast German ships, particularly ''Goeben'', who may interfere in that action. You will be notified by telegraph when you may consult with the French Admiral. Do not at this stage be brought to action against superior forces, except in combination with the French, as part of a general battle. The speed of your squadrons is sufficient to enable you to choose your moment. We shall hope to reinforce the Mediterranean, and you must husband your forces at the outset." Churchill's orders did not explicitly state what he meant by "superior forces." He later claimed that he was referring to "the Austrian Fleet against whose battleships it was not desirable that our three battle-cruisers should be engaged without battleship support."

Milne assembled his force at Malta on 1 August. On 2 August, he received instructions to shadow ''Goeben'' with two battlecruisers while maintaining a watch on the Adriatic, ready for a sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warfare. ...

by the Austrians. ''Indomitable'', ''Indefatigable'', five cruisers and eight destroyers commanded by Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

Ernest Troubridge

Admiral Sir Ernest Charles Thomas Troubridge, (15 July 1862 – 28 January 1926) was an officer of the Royal Navy who served during the First World War.

Troubridge was born into a family with substantial military connections, with several of hi ...

were sent to cover the Adriatic. ''Goeben'' had already departed but was sighted that same day at Taranto by the British Consul, who informed London. Fearing the German ships might be trying to escape to the Atlantic, the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

ordered that ''Indomitable'' and ''Indefatigable'' be sent west towards Gibraltar. Milne's other task of protecting French ships was complicated by the lack of any direct communications with the French navy, which had meanwhile postponed the sailing of the troop ships. The light cruiser was sent to search the Straits of Messina

The Strait of Messina ( it, Stretto di Messina, Sicilian: Strittu di Missina) is a narrow strait between the eastern tip of Sicily ( Punta del Faro) and the western tip of Calabria ( Punta Pezzo) in Southern Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian S ...

for ''Goeben''. However, by this time, on the morning of 3 August, Souchon had departed from Messina, heading west.

First contact

Without specific orders, Souchon had decided to position his ships off the coast of

Without specific orders, Souchon had decided to position his ships off the coast of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, ready to engage when hostilities commenced in order to attack French transport ships, which were headed toward Toulon. He planned to bombard the embarkation ports of Bône

Annaba ( ar, عنّابة, "Place of the Jujubes"; ber, Aânavaen), formerly known as Bon, Bona and Bône, is a seaport city in the northeastern corner of Algeria, close to the border with Tunisia. Annaba is near the small Seybouse River ...

and Philippeville

Philippeville (; wa, Flipveye) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Namur, Belgium. The Philippeville municipality includes the former municipalities of Fagnolle, Franchimont, Jamagne, Jamiolle, Merlemont, N ...

in French Algeria

French Algeria (french: Alger to 1839, then afterwards; unofficially , ar, الجزائر المستعمرة), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of French colonisation of Algeria. French rule in the region began in 1830 with the ...

. ''Goeben'' was heading for Philippeville, while ''Breslau'' was detached to deal with Bône. At 18:00 on 3 August, while still sailing west, he received word that Germany had declared war on France. Then, early on 4 August, Souchon received orders from Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz

Alfred Peter Friedrich von Tirpitz (19 March 1849 – 6 March 1930) was a German grand admiral, Secretary of State of the German Imperial Naval Office, the powerful administrative branch of the German Imperial Navy from 1897 until 1916. Prussi ...

reading: "Alliance with government of CUP

A cup is an open-top used to hold hot or cold liquids for pouring or drinking; while mainly used for drinking, it also can be used to store solids for pouring (e.g., sugar, flour, grains, salt). Cups may be made of glass, metal, china, clay, ...

concluded 3 August. Proceed at once to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

." So close to his targets, Souchon ignored the order and pushed on, flying the Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

flag as he approached, in order to evade detection. He carried out a shore bombardment at dawn before breaking off and heading back to Messina for more coal.

Under a pre-war agreement with Britain, France was able to concentrate her entire fleet in the Mediterranean, leaving the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

to ensure the security of France's Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

coast. Three squadrons of the French fleet were covering the transports. However, assuming that ''Goeben'' would continue west to Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, the French commander, Admiral de Lapeyrère, sent the "Groupe A" of his fleet to the west in order to make contact, but Souchon was heading east and so was able to slip away.

At 09:30 on 4 August Souchon made contact with the two British battlecruisers, ''Indomitable'' and ''Indefatigable'', which passed the German ships in the opposite direction. Neither force engaged as, unlike France, Britain had not yet declared war with Germany (the declaration would not be made until later that day, following the start of the German invasion of neutral Belgium). The British started shadowing ''Goeben'' and ''Breslau'' but were quickly outpaced by the Germans. Milne reported the contact and position, but neglected to inform the Admiralty that the German ships were heading east. Churchill therefore, still expecting them to threaten the French transports, authorised Milne to engage the German ships if they attacked. However, a meeting of the British Cabinet decided that hostilities could not start before a declaration of war, and at 14:00 Churchill was obliged to cancel his attack order.

Pursuit

The rated speed of ''Goeben'' was , but her damaged boilers meant she could only manage , and this was only achieved by working men and machinery to the limit; four stokers were killed by scalding

The rated speed of ''Goeben'' was , but her damaged boilers meant she could only manage , and this was only achieved by working men and machinery to the limit; four stokers were killed by scalding steam

Steam is a substance containing water in the gas phase, and sometimes also an aerosol of liquid water droplets, or air. This may occur due to evaporation or due to boiling, where heat is applied until water reaches the enthalpy of vaporization ...

. Fortunately for Souchon, both British battlecruisers were also suffering from problems with their boilers and were unable to keep ''Goeben''′s pace. The light cruiser maintained contact, while ''Indomitable'' and ''Indefatigable'' fell behind. In fog and fading light, ''Dublin'' lost contact off Cape San Vito

Partinico (Sicilian language, Sicilian: ''Partinicu'', Ancient Greek: ''Parthenikòn'', Παρθενικόν) is a city and ''comune'' in the Metropolitan City of Palermo, Sicily, southern Italy. It is from Palermo and from Trapani.

Main sights ...

on the north coast of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

at 19:37. ''Goeben'' and ''Breslau'' returned to Messina the following morning, by which time Britain and Germany were at war.

The Admiralty ordered Milne to respect Italian neutrality and stay outside a limit from the Italian coast—which precluded entrance into the passage of the Straits of Messina. Consequently, Milne posted guards on the exits from the Straits. Still expecting Souchon to head for the transports and the Atlantic, he placed two battlecruisers—''Inflexible'' and ''Indefatigable''—to cover the northern exit (which gave access to the western Mediterranean), while the southern exit of the Straits was covered by a single light cruiser, . Milne sent ''Indomitable'' west to coal at Bizerte, instead of south to Malta.Massie. ''Castles of Steel'', p. 39.

For Souchon, Messina was no haven. The Italian authorities insisted that he depart within 24 hours and delayed supplying coal. Provisioning his ships required ripping up the decks of German merchant steamers in harbour and manually shovelling their coal into his bunkers. By the evening of 6 August, despite the help of 400 volunteers from the merchantmen, he had only taken on which was insufficient to reach Constantinople. Further messages from Tirpitz made his predicament even more dire. He was informed that Austria would provide no naval aid in the Mediterranean and that the Ottoman Empire was still neutral and therefore he should no longer make for Constantinople. Faced with the alternative of seeking refuge at Pola, and probably remaining trapped for the rest of the war, Souchon chose to head for Constantinople anyway, his purpose being "to force the Ottoman Empire, even against their will, to spread the war to the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

against their ancient enemy, Russia."

Milne was instructed on 5 August to continue watching the Adriatic for signs of the Austrian fleet and to prevent the German ships joining them. He chose to keep his battlecruisers in the west, dispatching ''Dublin'' to join Troubridge's cruiser squadron in the Adriatic, which he believed would be able to intercept ''Goeben'' and ''Breslau''. Troubridge was instructed "not to get seriously engaged with superior forces," once again intended as a warning against engaging the Austrian fleet. When ''Goeben'' and ''Breslau'' emerged into the eastern Mediterranean on 6 August, they were met by ''Gloucester'', which, being outgunned, began to shadow the German ships.

Troubridge's squadron consisted of the armoured cruisers , , , and eight destroyers armed with torpedoes. The cruisers had guns versus the guns of ''Goeben'' and had armour a maximum of thick compared to the battlecruiser's armour belt. This meant that Troubridge's squadron was not only outranged and vulnerable to ''Goeben''′s powerful guns, but it was unlikely that his cruiser's guns could seriously damage the German ship at all, even at short range. In addition, the British ships were several knots slower than ''Goeben'', despite her damaged boilers, meaning that she could dictate the range of the battle if she spotted the British squadron in advance. Consequently, Troubridge considered his only chance was to locate and engage ''Goeben'' in favourable light, at dawn, with ''Goeben'' east of his ships, and ideally launch a torpedo attack with his destroyers; however, at least five of the destroyers did not have enough coal to keep up with the cruisers steaming at full speed. By 04:00 on 7 August, Troubridge realised he would not be able to intercept the German ships before daylight and after some deliberation he signalled Milne with his intentions to break off the chase, mindful of Churchill's ambiguous order to avoid engaging a "superior force." No reply was received until 10:00, by which time he had withdrawn to Zante to refuel.

Escape

Milne ordered ''Gloucester'' to disengage, still expecting Souchon to turn west, but it was apparent to ''Gloucester''′s captain that ''Goeben'' was fleeing. ''Breslau'' attempted to harass ''Gloucester'' into breaking off—Souchon had a collier waiting off the coast of

Milne ordered ''Gloucester'' to disengage, still expecting Souchon to turn west, but it was apparent to ''Gloucester''′s captain that ''Goeben'' was fleeing. ''Breslau'' attempted to harass ''Gloucester'' into breaking off—Souchon had a collier waiting off the coast of Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

and needed to shake his pursuer before he could rendezvous. ''Gloucester'' finally engaged ''Breslau'', hoping this would compel ''Goeben'' to drop back and protect the light cruiser. According to Souchon, ''Breslau'' was hit, but no damage was done. The action then broke off without further hits being scored. Finally, Milne ordered ''Gloucester'' to cease pursuit at Cape Matapan

Cape Matapan ( el, Κάβο Ματαπάς, Maniot dialect: Ματαπά), also named as Cape Tainaron or Taenarum ( el, Ακρωτήριον Ταίναρον), or Cape Tenaro, is situated at the end of the Mani Peninsula, Greece. Cape Matap ...

.

Shortly after midnight on 8 August Milne took his three battlecruisers and the light cruiser east. At 14:00 he received an incorrect signal from the Admiralty stating that Britain was at war with Austria; war would not be declared until 12 August and the order was countermanded four hours later, but Milne chose to guard the Adriatic rather than seek ''Goeben''. Finally, on 9 August, Milne was given clear orders to "chase ''Goeben'' which had passed Cape Matapan on the 7th steering north-east." Milne still did not believe that Souchon was heading for the Dardanelles, and so he resolved to guard the exit from the Aegean, unaware that ''Goeben'' did not intend to come out.

Souchon had replenished his coal off the Aegean island of Donoussa

Donousa ( el, Δονούσα, also Δενούσα ''Denousa''), and sometimes spelled Donoussa, is an island and a former community in the Cyclades, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Naxos and Lesser Cyc ...

on 9 August, and the German warships resumed their voyage to Constantinople. At 17:00 on 10 August, he reached the Dardanelles and awaited permission to pass through. Germany had for some time been courting the Committee of Union and Progress of the imperial government

The name imperial government (german: Reichsregiment) denotes two organs, created in 1500 and 1521, in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation to enable a unified political leadership, with input from the Princes. Both were composed of the em ...

, and it now used its influence to pressure the Turkish Minister of War, Enver Pasha, into granting the ship's passage, an act that would outrage Russia, which relied on the Dardanelles as its main all-season shipping route. In addition, the Germans managed to persuade Enver to order any pursuing British ships to be fired on. By the time Souchon received permission to enter the straits, his lookouts could see smoke on the horizon from approaching British ships.

Turkey was still a neutral country bound by treaty to prevent German ships from passing the straits. To get around this difficulty it was agreed that the ships should become part of the Turkish navy. On 16 August, having reached Constantinople, ''Goeben'' and ''Breslau'' were transferred to the Turkish Navy in a small ceremony, becoming respectively ''Yavuz Sultan Selim'' and ''Midilli'', though they retained their German crews with Souchon still in command. The initial reaction in Britain was one of satisfaction, that a threat had been removed from the Mediterranean. On 23 September, Souchon was appointed commander-in-chief of the Ottoman Navy.

Consequences

In August, Germany—still expecting a swift victory—was content for the Ottoman Empire to remain neutral. The mere presence of a powerful warship like ''Goeben'' in theSea of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara,; grc, Προποντίς, Προποντίδα, Propontís, Propontída also known as the Marmara Sea, is an inland sea located entirely within the borders of Turkey. It connects the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea via the ...

would be enough to occupy a British naval squadron guarding the Dardanelles. However, following German reverses at the First Battle of the Marne

The First Battle of the Marne was a battle of the First World War fought from 5 to 12 September 1914. It was fought in a collection of skirmishes around the Marne River Valley. It resulted in an Entente victory against the German armies in the ...

in September, and with Russian successes against Austria-Hungary, Germany began to regard the Ottoman Empire as a useful ally. Tensions began to escalate when the Ottoman Empire closed the Dardanelles to all shipping on 27 September, blocking Russia's exit from the Black Sea—that accounted for over 90 percent of Russia's import and export traffic.

Germany's gift of the two modern warships had an enormous positive impact on the Turkish population. At the outbreak of the war, Churchill had caused outrage when he "requisitioned" two almost completed Turkish battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

s in British shipyards, ''Sultan Osman I'' and ''Reshadieh'', which had been financed by public subscription at a cost of £6,000,000. Turkey was offered compensation of £1,000 per day for so long as the war might last, provided she remained neutral. (These ships were commissioned into the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

as and respectively.) The Turks had been neutral, though the navy had been pro-British (having purchased 40 warships from British shipyards) while the army was in favour of Germany, so the two incidents helped resolve the deadlock and the Ottoman Empire would join the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

.

Ottoman engagement

Continueddiplomacy

Diplomacy comprises spoken or written communication by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.Ronald Peter Barston, ''Modern diplomacy'', Pearson Education, 2006, p. 1 ...

from France and Russia attempted to keep the Ottoman Empire out of the war, but Germany was agitating for a commitment. In the aftermath of Souchon's daring dash to Constantinople, on 15 August 1914 the Ottomans canceled their maritime agreement with Britain and the Royal Navy mission under Admiral Limpus left by 15 September.

Finally, on 29 October, the point of no return was reached when Admiral Souchon took ''Goeben'', ''Breslau'' and a squadron of Turkish warships and launched the Black Sea Raid against the Russian ports of Novorossiysk

Novorossiysk ( rus, Новоросси́йск, p=nəvərɐˈsʲijsk; ady, ЦIэмэз, translit=Chəməz, p=t͡sʼɜmɜz) is a city in Krasnodar Krai, Russia. It is one of the largest ports on the Black Sea. It is one of the few cities hono ...

, Feodosia

uk, Феодосія, Теодосія crh, Kefe

, official_name = ()

, settlement_type=

, image_skyline = THEODOSIA 01.jpg

, imagesize = 250px

, image_caption = Genoese fortress of Caffa

, image_shield = Fe ...

, Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

, and Sevastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

. The ensuing political crises brought the Ottoman Empire into the war.

Royal Navy

While the consequences of the Royal Navy's failure to intercept ''Goeben'' and ''Breslau'' had not been immediately apparent, the humiliation of the "defeat" resulted in Admirals de Lapeyrère, Milne and Troubridge being censured. Milne was recalled from the Mediterranean and did not hold another command until retirement at his own request in 1919, his planned assumption of the Nore command having been cancelled in 1916 due to "other exigencies." The Admiralty repeatedly stated that Milne had been exonerated of all blame. For his failure to engage ''Goeben'' with hiscruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

s, Troubridge was court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

led in November on the charge that "he did forbear to chase His Imperial German Majesty's ship ''Goeben'', being an enemy then flying." The charge was not proved on the grounds that he was under orders not to engage a "superior force." However, he was never given another sea-going command but did valuable service, co-operating with the Serbs on the Balkan and being given command of a force on the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

in 1915 against the Austro-Hungarians. He eventually retired as a full Admiral.

Long-term consequences

Although a relatively minor 'action' and perhaps not widely known historical event, the escape of ''Goeben'' to Constantinople and its eventual annexation to Turkey ultimately precipitated some of the most dramatic naval chases of the 20th century. It also assisted in helping to shape the eventual splitting up of the Ottoman Empire into the many states we know today. General Ludendorff stated in his memoirs that he believed the entry of the Turks into the war allowed the outnumbered Central Powers to fight on for two years longer than they would have been able on their own, a view shared by historian Ian F.W. Beckett. The war was extended to theMiddle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

with main fronts of Gallipoli

The Gallipoli peninsula (; tr, Gelibolu Yarımadası; grc, Χερσόνησος της Καλλίπολης, ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles ...

, the Sinai and Palestine, Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

, and the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

. The course of the war in the Balkans was also influenced by the entry of the Ottoman Empire on the side of the Central Powers. Had the war ended in 1916, some of the bloodiest engagements, such as the Battle of the Somme

The Battle of the Somme ( French: Bataille de la Somme), also known as the Somme offensive, was a battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place bet ...

, would have been avoided. The United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

might not have been drawn from its policy of isolation to intervene in a foreign war.

In allying with the Central Powers, Turkey shared their fate in ultimate defeat. This gave the allies the opportunity to carve up the collapsed Ottoman Empire to suit their political whims. Many new nations were created including Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

, Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the A ...

and Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

.

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * *External links

*Superior Force: The Conspiracy Behind the Escape of ''Goeben'' and ''Breslau''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Goeben And Breslau Mediterranean naval operations of World War I Naval battles of World War I involving France Naval battles of World War I involving Germany Naval battles of World War I involving the United Kingdom Naval battles of World War I involving Russia Naval battles of World War I involving the Ottoman Empire Conflicts in 1914 1914 in the Ottoman Empire July 1914 events August 1914 events