Provisional IRA on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an

The original IRA was formed in 1913 as the

The original IRA was formed in 1913 as the

The IRA split into "Provisional" and "Official" factions in December 1969, after an IRA convention was held in

The IRA split into "Provisional" and "Official" factions in December 1969, after an IRA convention was held in

In January 1970, the Army Council decided to adopt a three-stage strategy; defence of nationalist areas, followed by a combination of defence and retaliation, and finally launching a guerrilla campaign against the British Army. The Official IRA was opposed to such a campaign because they felt it would lead to sectarian conflict, which would defeat their strategy of uniting the workers from both sides of the sectarian divide. The Provisional IRA's strategy was to use force to cause the collapse of the

In January 1970, the Army Council decided to adopt a three-stage strategy; defence of nationalist areas, followed by a combination of defence and retaliation, and finally launching a guerrilla campaign against the British Army. The Official IRA was opposed to such a campaign because they felt it would lead to sectarian conflict, which would defeat their strategy of uniting the workers from both sides of the sectarian divide. The Provisional IRA's strategy was to use force to cause the collapse of the  On 22 June the IRA announced that a ceasefire would begin at midnight on 26 June, in anticipation of talks with the British government. Two days later Ó Brádaigh and Ó Conaill held a

On 22 June the IRA announced that a ceasefire would begin at midnight on 26 June, in anticipation of talks with the British government. Two days later Ó Brádaigh and Ó Conaill held a

The prison protest against criminalisation culminated in the 1981 Irish hunger strike, when seven IRA and three

The prison protest against criminalisation culminated in the 1981 Irish hunger strike, when seven IRA and three

The IRA responded to Brooke's speech by declaring a three-day ceasefire over Christmas, the first in fifteen years. Afterwards the IRA intensified the bombing campaign in England, planting 36 bombs in 1991 and 57 in 1992, up from 15 in 1990. The

The IRA responded to Brooke's speech by declaring a three-day ceasefire over Christmas, the first in fifteen years. Afterwards the IRA intensified the bombing campaign in England, planting 36 bombs in 1991 and 57 in 1992, up from 15 in 1990. The  On 9 February 1996 a statement from the Army Council was delivered to the Irish national broadcaster

On 9 February 1996 a statement from the Army Council was delivered to the Irish national broadcaster

* 1,000 rifles

* 2 tonnes of the plastic explosive

* 1,000 rifles

* 2 tonnes of the plastic explosive

Kevin McGuigan's son claims his father 'exonerated' over Gerard 'Jock' Davison murder

, ''

In the early days of

In the early days of

The IRA was responsible for more deaths than any other organisation during the Troubles. Two detailed studies of deaths in the Troubles, the

The IRA was responsible for more deaths than any other organisation during the Troubles. Two detailed studies of deaths in the Troubles, the

The IRA's goal was an all-Ireland

The IRA's goal was an all-Ireland

CAIN (Conflict Archive Internet) Archive of IRA statements

Behind The Mask: The IRA & Sinn Fein

PBS Frontline documentary on the subject

The IRA and American funding

from th

Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

* J. Bowyer Bell, Bell, J. Bowyer.

Dragonworld (II): Deception, Tradecraft, and the Provisional IRA

" ''International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence''. Volume 8, No. 1., Spring 1995. p. 21–50. Published online 9 January 2008

Available at

ResearchGate

"Operation Banner: An analysis of military operations in Northern Ireland"

{{Authority control Provisional Irish Republican Army, 1969 establishments in Ireland 1969 establishments in Northern Ireland Proscribed paramilitary organisations in Northern Ireland Irish republican militant groups National liberation armies Organisations designated as terrorist by the United Kingdom Organizations based in Europe designated as terrorist Organised crime groups in Ireland Military wings of political parties

Irish republican

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The develop ...

paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

, facilitate Irish reunification

United Ireland, also referred to as Irish reunification, is the proposition that all of Ireland should be a single sovereign state. At present, the island is divided politically; the sovereign Republic of Ireland has jurisdiction over the maj ...

and bring about an independent, socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

encompassing all of Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

. It was the most active republican paramilitary group during the Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

. It saw itself as the army of the all-island Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( ga, Poblacht na hÉireann or ) was an unrecognised revolutionary state that declared its independence from the United Kingdom in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdiction over the whole island of Ireland, but by ...

and as the sole legitimate successor to the original IRA from the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

. It was designated a terrorist organisation in the United Kingdom and an unlawful organisation in the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. A ...

, both of whose authority it rejected.

The Provisional IRA emerged in December 1969, due to a split within the previous incarnation of the IRA and the broader Irish republican movement

Irish Republican Movement is a dissident republican vigilante group founded in April 2018. They formed as a splinter group of Óglaigh na hÉireann, after they went on ceasefire in 2018.

See also

* Republican movement (Ireland) The republic ...

. It was initially the minority faction in the split compared to the Official IRA

The Official Irish Republican Army or Official IRA (OIRA; ) was an Irish republican paramilitary group whose goal was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and create a "workers' republic" encompassing all of Ireland. It emerged ...

, but became the dominant faction by 1972. The Troubles had begun shortly before when a largely Catholic, nonviolent civil rights campaign was met with violence from both Ulster loyalists and the Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the Royal ...

(RUC), culminating in the August 1969 riots and deployment of British soldiers. The IRA initially focused on defence of Catholic areas, but it began an offensive campaign in 1970 that was aided by weapons supplied by Irish American

, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption = Irish Americans, % of population by state

, caption = Notable Irish Americans

, population =

36,115,472 (10.9%) alone ...

sympathisers and Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by ''The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spellin ...

. It used guerrilla tactics against the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

and RUC in both rural and urban areas, and carried out a bombing campaign in Northern Ireland and England against military, political and economic targets, and British military targets in Europe.

The Provisional IRA declared a final ceasefire in July 1997, after which its political wing Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

was admitted into multi-party peace talks on the future of Northern Ireland. These resulted in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA), or Belfast Agreement ( ga, Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta or ; Ulster-Scots: or ), is a pair of agreements signed on 10 April 1998 that ended most of the violence of The Troubles, a political conflict in No ...

, and in 2005 the IRA formally ended its armed campaign and decommissioned its weapons under the supervision of the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning

The Independent International Commission on Decommissioning (IICD) was established to oversee the decommissioning of paramilitary weapons in Northern Ireland, as part of the peace process.

Legislation and organisation

An earlier international bo ...

. Several splinter group

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

s have been formed as a result of splits within the IRA, including the Continuity IRA

The Continuity Irish Republican Army (Continuity IRA or CIRA), styling itself as the Irish Republican Army (), is an Irish republican paramilitary group that aims to bring about a united Ireland. It claims to be a direct continuation of the or ...

and the Real IRA

The Real Irish Republican Army, or Real IRA (RIRA), is a dissident Irish republican paramilitary group that aims to bring about a United Ireland. It formed in 1997 following a split in the Provisional IRA by dissident members, who rejected the ...

, both of which are still active in the dissident Irish republican campaign

The dissident Irish republican campaign began at the end of the Troubles, a 30-year political conflict in Northern Ireland. Since the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA or PIRA) called a ceasefire and ended its campaign in 1997, breakaway ...

. The IRA's armed campaign, primarily in Northern Ireland but also in England and mainland Europe, killed over 1,700 people, including roughly 1,000 members of the British security forces, and 500–644 civilians. In addition 275–300 members of the IRA were killed during the conflict.

History

Origins

The original IRA was formed in 1913 as the

The original IRA was formed in 1913 as the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers ( ga, Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force or Irish Volunteer Army, was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in respons ...

, at a time when all of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

. The Volunteers took part in the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the a ...

against British rule

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was himsel ...

in 1916, and the War of Independence

This is a list of wars of independence (also called liberation wars). These wars may or may not have been successful in achieving a goal of independence.

List

See also

* Lists of active separatist movements

* List of civil wars

* List of o ...

that followed the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

by the revolutionary parliament Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland read ...

in 1919, during which they came to be known as the IRA. Ireland was partitioned into Southern Ireland

Southern Ireland, South Ireland or South of Ireland may refer to:

*The southern part of the island of Ireland

*Southern Ireland (1921–1922), a former constituent part of the United Kingdom

*Republic of Ireland, which is sometimes referred to as ...

and Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

by the Government of Ireland Act 1920

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 (10 & 11 Geo. 5 c. 67) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act's long title was "An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland"; it is also known as the Fourth Home Rule Bill ...

, and following the implementation of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

in 1922 Southern Ireland, renamed the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between th ...

, became a self-governing dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

while Northern Ireland chose to remain under home rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

as part of the United Kingdom. The Treaty caused a split in the IRA, the pro-Treaty IRA were absorbed into the National Army, which defeated the anti-Treaty IRA

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

in the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. Subsequently, while denying the legitimacy of the Free State, the surviving elements of the anti-Treaty IRA focused on overthrowing the Northern Ireland state and the achievement of a united Ireland

United Ireland, also referred to as Irish reunification, is the proposition that all of Ireland should be a single sovereign state. At present, the island is divided politically; the sovereign Republic of Ireland has jurisdiction over the maj ...

, carrying out a bombing campaign in England in 1939 and 1940, a campaign in Northern Ireland in the 1940s, and the Border campaign of 1956–1962. Following the failure of the Border campaign, internal debate took place regarding the future of the IRA. Chief-of-staff Cathal Goulding

Cathal Goulding ( ga, Cathal Ó Goillín; 2 January 1923 – 26 December 1998) was Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army and the Official IRA.

Early life and career

One of seven children born on East Arran Street in north Dublin to an ...

wanted the IRA to adopt a socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

agenda and become involved in politics, while traditional republicans such as Seán Mac Stíofáin

Seán Mac Stíofáin (born John Edward Drayton Stephenson; 17 February 1928 – 18 May 2001) was an English-born chief of staff of the Provisional IRA, a position he held between 1969 and 1972.

Childhood

Although he used the Gaelicised ver ...

wanted to increase recruitment and rebuild the IRA.

Following partition, Northern Ireland became a de facto one-party state governed by the Ulster Unionist Party

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule movem ...

in the Parliament of Northern Ireland

The Parliament of Northern Ireland was the home rule legislature of Northern Ireland, created under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, which sat from 7 June 1921 to 30 March 1972, when it was suspended because of its inability to restore ord ...

, in which Catholics viewed themselves as second-class citizen

A second-class citizen is a person who is systematically and actively discriminated against within a state or other political jurisdiction, despite their nominal status as a citizen or a legal resident there. While not necessarily slaves, ...

s. Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

s were given preference in jobs and housing, and local government constituencies were gerrymandered

In representative democracies, gerrymandering (, originally ) is the political manipulation of electoral district boundaries with the intent to create undue advantage for a party, group, or socioeconomic class within the constituency. The m ...

in places such as Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

. Policing was carried out by the armed Royal Ulster Constabulary

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2001. It was founded on 1 June 1922 as a successor to the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC)Richard Doherty, ''The Thin Green Line – The History of the Royal ...

(RUC) and the B-Specials

The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC; commonly called the "B-Specials" or "B Men") was a quasi-military reserve special constable police force in what would later become Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, shortly before the par ...

, both of which were almost exclusively Protestant. In the mid-1960s tension between the Catholic and Protestant communities was increasing. In 1966 Ireland celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising, prompting fears of a renewed IRA campaign. Feeling under threat, Protestants formed the Ulster Volunteer Force

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) is an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group. Formed in 1965, it first emerged in 1966. Its first leader was Gusty Spence, a former British Army soldier from Northern Ireland. The group undertook an armed campaig ...

(UVF), a paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

group which killed three people in May 1966, two of them Catholic men. In January 1967 the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

) was an organisation that campaigned for civil rights in Northern Ireland during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Formed in Belfast on 9 April 1967,

(NICRA) was formed by a diverse group of people, including IRA members and liberal unionists. Civil rights marches by NICRA and a similar organisation, People's Democracy, protesting against discrimination were met by counter-protest

A counter-protest (also spelled counterprotest) is a protest action which takes place within the proximity of an ideologically opposite protest. The purposes of counter-protests can range from merely voicing opposition to the objective of the othe ...

s and violent clashes with loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

, including the Ulster Protestant Volunteers

The Ulster Protestant Volunteers was a Ulster loyalism, loyalist and Reformed fundamentalism, Reformed fundamentalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. They were active between 1966 and 1969 and closely linked to the Ulster Constitution Def ...

, a paramilitary group led by Ian Paisley

Ian Richard Kyle Paisley, Baron Bannside, (6 April 1926 – 12 September 2014) was a Northern Irish loyalist politician and Protestant religious leader who served as leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) from 1971 to 2008 and First ...

.

Marches marking the Ulster Protestant celebration The Twelfth

The Twelfth (also called Orangemen's Day) is an Ulster Protestant celebration held on 12 July. It began in the late 18th century in Ulster. It celebrates the Glorious Revolution (1688) and victory of Protestant King William III of England, W ...

in July 1969 led to riots and violent clashes in Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

, Derry and elsewhere. The following month a three-day riot began in the Catholic Bogside

The Bogside is a neighbourhood outside the city walls of Derry, Northern Ireland. The large gable-wall murals by the Bogside Artists, Free Derry Corner and the Gasyard Féile (an annual music and arts festival held in a former gasyard) are pop ...

area of Derry, following a march by the Protestant Apprentice Boys of Derry

The Apprentice Boys of Derry is a Protestant fraternal society with a worldwide membership of over 10,000, founded in 1814 and based in the city of Derry, Northern Ireland. There are branches in Ulster and elsewhere in Ireland, Scotland, Engla ...

. The Battle of the Bogside

The Battle of the Bogside was a large three-day riot that took place from 12 to 14 August 1969 in Derry, Northern Ireland. Thousands of Catholic/Irish nationalist residents of the Bogside district, organised under the Derry Citizens' Defence ...

caused Catholics in Belfast to riot in solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictio ...

with the Bogsiders and to try to prevent RUC reinforcements being sent to Derry, sparking retaliation by Protestant mobs. The subsequent arson attack

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, water ...

s, damage to property and intimidation forced 1,505 Catholic families and 315 Protestant families to leave their homes in Belfast in the Northern Ireland riots of August 1969 The riots resulted in 275 buildings being destroyed or requiring major repairs, 83.5% of them occupied by Catholics. A number of people were killed on both sides, some by the police, and the British Army were deployed to Northern Ireland. The IRA had been poorly armed and failed to properly defend Catholic areas from Protestant attacks, which had been considered one of its roles since the 1920s. Veteran republicans were critical of Goulding and the IRA's Dublin leadership which, for political reasons, had refused to prepare for aggressive action in advance of the violence. On 24 August a group including Joe Cahill

, birth_date =

, death_date =

, birth_place = Belfast, Ireland

, death_place = Belfast, Northern Ireland

, image = Joe Cahill.png

, caption = Cahill, early 1990s.

, allegiance = Provisional Irish Republican ...

, Seamus Twomey

Seamus Twomey ( ga, Séamus Ó Tuama; 5 November 1919 – 12 September 1989) was an Irish republican activist, militant, and twice chief of staff of the Provisional IRA.

Biography

Born in Belfast on Marchioness Street,Volunteer Seamus Twomey, 19 ...

, Dáithí Ó Conaill

Dáithí Ó Conaill (English: ''David O'Connell'') (May 1938 – 1 January 1991) was an Irish republican, a member of the IRA Army Council of the Provisional IRA, and vice-president of Sinn Féin and Republican Sinn Féin. He was also the firs ...

, Billy McKee

Billy McKee ( ga, Liam Mac Aoidh; 12 November 1921 – 11 June 2019) was an Irish republican and a founding member and leader of the Provisional Irish Republican Army.

Early life

McKee was born in Belfast on 12 November 1921, and joined the Iri ...

, and Jimmy Steele came together in Belfast and decided to remove the pro-Goulding Belfast leadership of Billy McMillen

William "Billy" McMillen (19 May 1927 – 28 April 1975), aka Liam McMillen, was an Irish republican activist and an officer of the Official Irish Republican Army (OIRA) from Belfast, Northern Ireland. He was killed in 1975, in a feud with t ...

and Jim Sullivan and return to traditional militant republicanism. On 22 September Twomey, McKee, and Steele were among sixteen armed IRA men who confronted the Belfast leadership over the failure to adequately defend Catholic areas. A compromise was agreed where McMillen stayed in command, but he was not to have any communication with the IRA's Dublin based leadership.

1969 split

The IRA split into "Provisional" and "Official" factions in December 1969, after an IRA convention was held in

The IRA split into "Provisional" and "Official" factions in December 1969, after an IRA convention was held in Boyle, County Roscommon

Boyle (; ) is a town in County Roscommon, Ireland. It is located at the foot of the Curlew Mountains near Lough Key in the north of the county. Carrowkeel Megalithic Cemetery, the Drumanone Dolmen and the lakes of Lough Arrow and Lough Gara a ...

, Republic of Ireland. The two main issues at the convention were a resolution

Resolution(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Resolution (debate), the statement which is debated in policy debate

* Resolution (law), a written motion adopted by a deliberative body

* New Year's resolution, a commitment that an individual mak ...

to enter into a "National Liberation Front" with radical left-wing groups, and a resolution to end abstentionism

Abstentionism is standing for election to a deliberative assembly while refusing to take up any seats won or otherwise participate in the assembly's business. Abstentionism differs from an election boycott in that abstentionists participate in ...

, which would allow participation in the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

, Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

, and Northern Ireland parliaments. Traditional republicans refused to vote on the "National Liberation Front" and it was passed by twenty-nine votes to seven. The traditionalists argued strongly against the ending of abstentionism, and the official minutes report the resolution passed by twenty-seven votes to twelve.

Following the convention the traditionalists canvassed support throughout Ireland, with IRA director of intelligence Mac Stíofáin meeting the disaffected members of the IRA in Belfast. Shortly after, the traditionalists held a convention which elected a "Provisional" Army Council, composed of Mac Stíofáin, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh

Ruairí Ó Brádaigh (; born Peter Roger Casement Brady; 2 October 1932 – 5 June 2013) was an Irish republican political and military leader. He was Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) from 1958 to 1959 and again from 1960 to 19 ...

, Paddy Mulcahy

Paddy may refer to:

People

*Paddy (given name), a list of people with the given name or nickname

*An ethnic slur for an Irishman

Birds

*Paddy (pigeon), a Second World War carrier pigeon

*Snowy sheathbill or paddy, a bird species

*Black-faced sh ...

, Sean Tracey

Sean Patrick Tracey (born November 14, 1980) is a former American professional baseball right-handed pitcher. He appeared in seven games with the Chicago White Sox in 2006, all as a relief pitcher.

College

Tracey played both football and basebal ...

, Leo Martin

Leo Martin ( sr-cyr, Лео Мартин, born on 6 March 1942) is a Serbian and former Yugoslav pop singer. He started his career in the early 1960s in jazz bands as an instrumentalist and vocalist. In 1964, he moved with his band to West Germa ...

, Ó Conaill, and Cahill. The term provisional was chosen to mirror the 1916 Provisional Government of the Irish Republic, and also to designate it as temporary pending ratification

Ratification is a principal's approval of an act of its agent that lacked the authority to bind the principal legally. Ratification defines the international act in which a state indicates its consent to be bound to a treaty if the parties inten ...

by a further IRA convention. Nine out of thirteen IRA units in Belfast sided with the "Provisional" Army Council in December 1969, roughly 120 activists and 500 supporters. The Provisional IRA issued their first public statement on 28 December 1969, stating:

We declare our allegiance to the 32 county Irish republic, proclaimed at Easter 1916, established by the first Dáil Éireann in 1919, overthrown by force of arms in 1922 and suppressed to this day by the existing British-imposed six-county and twenty-six-county partition states... We call on the Irish people at home and in exile for increased support towards defending our people in the North and the eventual achievement of the full political, social, economic and cultural freedom of Ireland.The Irish republican political party

Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

split along the same lines on 11 January 1970 in Dublin, when a third of the delegates walked out of the party's highest deliberative body, the ard fheis

or ''ardfheis'' ( , ; "high assembly"; plural ''ardfheiseanna'') is the name used by many Irish political parties for their annual party conference. The term was first used by Conradh na Gaeilge, the Irish language cultural organisation, for it ...

, in protest at the party leadership's attempt to force through the ending of abstentionism, despite its failure to achieve a two-thirds majority vote of delegates required to change the policy. The delegates that walked out reconvened at another venue where Mac Stíofáin, Ó Brádaigh and Mulcahy from the "Provisional" Army Council were elected to the Caretaker Executive of "Provisional" Sinn Féin. Despite the declared support of that faction of Sinn Féin, the early Provisional IRA avoided political activity, instead relying on physical force republicanism

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The developm ...

. £100,000 was donated by the Fianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil (, ; meaning 'Soldiers of Destiny' or 'Warriors of Fál'), officially Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party ( ga, audio=ga-Fianna Fáil.ogg, Fianna Fáil – An Páirtí Poblachtánach), is a conservative and Christian- ...

-led Irish government

The Government of Ireland ( ga, Rialtas na hÉireann) is the cabinet that exercises executive authority in Ireland.

The Constitution of Ireland vests executive authority in a government which is headed by the , the head of government. The governm ...

in 1969 to "defence committees" in Catholic areas, some of which ended up in the hands of the IRA. This resulted in the 1970 Arms Crisis

The Arms Crisis was a political scandal in the Republic of Ireland in 1970 in which Charles Haughey and Neil Blaney were dismissed as cabinet ministers for alleged involvement in a conspiracy to smuggle arms to the Irish Republican Army in North ...

where criminal charges were pursued against two former government ministers and others including John Kelly John or Jack Kelly may refer to:

People Academics and scientists

* John Kelly (engineer), Irish professor, former Registrar of University College Dublin

*John Kelly (scholar) (1750–1809), at Douglas, Isle of Man

*John Forrest Kelly (1859–1922) ...

, an IRA volunteer

Volunteering is a voluntary act of an individual or group freely giving time and labor for community service. Many volunteers are specifically trained in the areas they work, such as medicine, education, or emergency rescue. Others serve ...

from Belfast. The Provisional IRA maintained the principles of the pre-1969 IRA, considering both British rule in Northern Ireland and the government of the Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. A ...

to be illegitimate, and the Army Council to be the provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

of the all-island Irish Republic

The Irish Republic ( ga, Poblacht na hÉireann or ) was an unrecognised revolutionary state that declared its independence from the United Kingdom in January 1919. The Republic claimed jurisdiction over the whole island of Ireland, but by ...

. This belief was based on a series of perceived political inheritances which constructed a legal continuity from the Second Dáil

The Second Dáil () was Dáil Éireann as it convened from 16 August 1921 until 8 June 1922. From 1919 to 1922, Dáil Éireann was the revolutionary parliament of the self-proclaimed Irish Republic. The Second Dáil consisted of members elected ...

of 1921–1922. The IRA recruited many young nationalists from Northern Ireland who had not been involved in the IRA before, but had been radicalised by the violence that broke out in 1969. These people became known as "sixty niners", having joined after 1969. The IRA adopted the phoenix

Phoenix most often refers to:

* Phoenix (mythology), a legendary bird from ancient Greek folklore

* Phoenix, Arizona, a city in the United States

Phoenix may also refer to:

Mythology

Greek mythological figures

* Phoenix (son of Amyntor), a ...

as the symbol of the Irish republican rebirth in 1969, one of its slogans was "out of the ashes rose the Provisionals", representing the IRA's resurrection from the ashes of burnt-out Catholic areas of Belfast.

Initial phase

In January 1970, the Army Council decided to adopt a three-stage strategy; defence of nationalist areas, followed by a combination of defence and retaliation, and finally launching a guerrilla campaign against the British Army. The Official IRA was opposed to such a campaign because they felt it would lead to sectarian conflict, which would defeat their strategy of uniting the workers from both sides of the sectarian divide. The Provisional IRA's strategy was to use force to cause the collapse of the

In January 1970, the Army Council decided to adopt a three-stage strategy; defence of nationalist areas, followed by a combination of defence and retaliation, and finally launching a guerrilla campaign against the British Army. The Official IRA was opposed to such a campaign because they felt it would lead to sectarian conflict, which would defeat their strategy of uniting the workers from both sides of the sectarian divide. The Provisional IRA's strategy was to use force to cause the collapse of the Northern Ireland government

The government of Northern Ireland is, generally speaking, whatever political body exercises political authority over Northern Ireland. A number of separate systems of government exist or have existed in Northern Ireland.

Following the partitio ...

and to inflict such heavy casualties on the British Army that the British government would be forced by public opinion to withdraw from Ireland. Mac Stíofáin decided they would "escalate, escalate and escalate", in what the British Army would later describe as a "classic insurgency

An insurgency is a violent, armed rebellion against authority waged by small, lightly armed bands who practice guerrilla warfare from primarily rural base areas. The key descriptive feature of insurgency is its asymmetric nature: small irregu ...

". In October 1970 the IRA began a bombing campaign against economic targets; by the end of the year there had been 153 explosions. The following year it was responsible for the vast majority of the 1,000 explosions that occurred in Northern Ireland. The strategic aim behind the bombings was to target businesses and commercial premises to deter investment and force the British government to pay compensation, increasing the financial cost of keeping Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom. The IRA also believed that the bombing campaign would tie down British soldiers in static positions guarding potential targets, preventing their deployment in counter-insurgency

Counterinsurgency (COIN) is "the totality of actions aimed at defeating irregular forces". The Oxford English Dictionary defines counterinsurgency as any "military or political action taken against the activities of guerrillas or revolutionar ...

operations. Loyalist paramilitaries, including the UVF, carried out campaigns aimed at thwarting the IRA's aspirations and maintaining the political union with Britain. Loyalist paramilitaries tended to target Catholics with no connection to the republican movement, seeking to undermine support for the IRA.

As a result of escalating violence, internment without trial was introduced by the Northern Ireland government on 9 August 1971, with 342 suspects arrested in the first twenty-four hours. Despite loyalist violence also increasing, all of those arrested were republicans, including political activist

A political movement is a collective attempt by a group of people to change government policy or social values. Political movements are usually in opposition to an element of the status quo, and are often associated with a certain ideology. Some t ...

s not associated with the IRA and student civil rights leaders. The one-sided nature of internment united all Catholics in opposition to the government, and riots broke out in protest across Northern Ireland. Twenty-two people were killed in the next three days, including six civilians killed by the British Army as part of the Ballymurphy massacre

The Ballymurphy massacre was a series of incidents between 9 and 11 August 1971, in which the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment of the British Army killed at least nine civilians in Ballymurphy, Belfast, Northern Ireland, as part of Operation ...

on 9 August, and in Belfast 7,000 Catholics and 2,000 Protestants were forced from their homes by the rioting. The introduction of internment dramatically increased the level of violence, in the seven months prior to internment 34 people had been killed, 140 people were killed between the introduction of internment and the end of the year, including thirty soldiers and eleven RUC officers. Internment boosted IRA recruitment, and in Dublin the Taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government, or prime minister, of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The office is appointed by the president of Ireland upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Oireachtas, Ireland's national legisl ...

, Jack Lynch

John Mary Lynch (15 August 1917 – 20 October 1999) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Taoiseach from 1966 to 1973 and 1977 to 1979, Leader of Fianna Fáil from 1966 to 1979, Leader of the Opposition from 1973 to 1977, Minister ...

, abandoned a planned idea to introduce internment in the Republic of Ireland. IRA recruitment further increased after Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday may refer to:

Historical events Canada

* Bloody Sunday (1923), a day of police violence during a steelworkers' strike for union recognition in Sydney, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

* Bloody Sunday (1938), police violence agai ...

in Derry on 30 January 1972, when the British Army killed fourteen unarmed civilians during an anti-internment march. Due to the deteriorating security situation in Northern Ireland the British government suspended the Northern Ireland parliament and imposed direct rule Direct rule is when an imperial or central power takes direct control over the legislature, executive and civil administration of an otherwise largely self-governing territory.

Examples Chechnya

In 1991, Chechen separatists declared independence o ...

in March 1972. The suspension of the Northern Ireland parliament was a key objective of the IRA, in order to directly involve the British government in Northern Ireland, as the IRA wanted the conflict to be seen as one between Ireland and Britain. In May 1972 the Official IRA called a ceasefire, leaving the Provisional IRA as the sole active republican paramilitary organisation. New recruits saw the Official IRA as existing for the purpose of defence in contrast to the Provisional IRA as existing for the purpose of attack, increased recruitment and defection

In politics, a defector is a person who gives up allegiance to one state in exchange for allegiance to another, changing sides in a way which is considered illegitimate by the first state. More broadly, defection involves abandoning a person, ca ...

s from the Official IRA to the Provisional IRA led to the latter becoming the dominant organisation.

On 22 June the IRA announced that a ceasefire would begin at midnight on 26 June, in anticipation of talks with the British government. Two days later Ó Brádaigh and Ó Conaill held a

On 22 June the IRA announced that a ceasefire would begin at midnight on 26 June, in anticipation of talks with the British government. Two days later Ó Brádaigh and Ó Conaill held a press conference

A press conference or news conference is a media event in which notable individuals or organizations invite journalists to hear them speak and ask questions. Press conferences are often held by politicians, corporations, non-governmental organ ...

in Dublin to announce the Éire Nua

Éire Nua, or "New Ireland", was a proposal supported by the Provisional IRA and Sinn Féin during the 1970s and early 1980s for a federal United Ireland. The proposal was particularly associated with the Dublin-based leadership group centred on ...

(New Ireland) policy, which advocated an all-Ireland federal

Federal or foederal (archaic) may refer to:

Politics

General

*Federal monarchy, a federation of monarchies

*Federation, or ''Federal state'' (federal system), a type of government characterized by both a central (federal) government and states or ...

republic, with devolved governments and parliaments for each of the four historic provinces of Ireland

There have been four Provinces of Ireland: Connacht (Connaught), Leinster, Munster, and Ulster. The Irish language, Irish word for this territorial division, , meaning "fifth part", suggests that there were once five, and at times Kingdom_of_ ...

. This was designed to deal with the fears of unionists over a united Ireland, an Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

parliament with a narrow Protestant majority would provide them with protection for their interests. The British government held secret talks with the republican leadership on 7 July, with Mac Stíofáin, Ó Conaill, Ivor Bell

Ivor Malachy Bell (born 1936/1937) is an Irish republican, and a former volunteer in the Belfast Brigade of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) who later became Chief of Staff on the Army Council.

IRA career

Bell was involved with t ...

, Twomey, Gerry Adams

Gerard Adams ( ga, Gearóid Mac Ádhaimh; born 6 October 1948) is an Irish republican politician who was the president of Sinn Féin between 13 November 1983 and 10 February 2018, and served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for Louth from 2011 to 2020 ...

, and Martin McGuinness

James Martin Pacelli McGuinness ( ga, Séamus Máirtín Pacelli Mag Aonghusa; 23 May 1950 – 21 March 2017) was an Irish republican politician and statesman from Sinn Féin and a leader within the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) during ...

flying to England to meet a British delegation led by William Whitelaw

William Stephen Ian Whitelaw, 1st Viscount Whitelaw, (28 June 1918 – 1 July 1999) was a British Conservative Party politician who served in a wide number of Cabinet positions, most notably as Home Secretary from 1979 to 1983 and as ''de fac ...

. Mac Stíofáin made demands including British withdrawal, removal of the British Army from sensitive areas, and a release of republican prisoners and an amnesty for fugitives. The British refused and the talks broke up, and the IRA's ceasefire ended on 9 July. In late 1972 and early 1973 the IRA's leadership was being depleted by arrests on both sides of the Irish border, with Mac Stíofáin, Ó Brádaigh and McGuinness all imprisoned for IRA membership. Due to the crisis the IRA bombed London in March 1973, as the Army Council believed bombs in England would have a greater impact on British public opinion. This was followed by an intense period of IRA activity in England that left forty-five people dead by the end of 1974, including twenty-one civilians killed in the Birmingham pub bombings

The Birmingham pub bombings were carried out on 21 November 1974, when bombs exploded in two public houses in Birmingham, England, killing 21 people and injuring 182 others.

The Provisional Irish Republican Army never officially admitted respo ...

.

Following an IRA ceasefire over the Christmas period in 1974 and a further one in January 1975, on 8 February the IRA issued a statement suspending "offensive military action" from six o'clock the following day. A series of meetings took place between the IRA's leadership and British government representatives throughout the year, with the IRA being led to believe this was the start of a process of British withdrawal. Occasional IRA violence occurred during the ceasefire, with bombs in Belfast, Derry, and South Armagh. The IRA was also involved in tit for tat

Tit for tat is an English saying meaning "equivalent retaliation". It developed from "tip for tap", first recorded in 1558.

It is also a highly effective strategy in game theory. An agent using this strategy will first cooperate, then subseque ...

sectarian killings of Protestant civilians, in retaliation for sectarian killings by loyalist paramilitaries. By July the Army Council was concerned at the progress of the talks, concluding there was no prospect of a lasting peace without a public declaration by the British government of their intent to withdraw from Ireland. In August there was a gradual return to the armed campaign, and the truce effectively ended on 22 September when the IRA set off 22 bombs across Northern Ireland. The old guard leadership of Ó Brádaigh, Ó Conaill, and McKee were criticised by a younger generation of activists following the ceasefire, and their influence in the IRA slowly declined. The younger generation viewed the ceasefire as being disastrous for the IRA, causing the organisation irreparable damage and taking it close to being defeated. The Army Council was accused of falling into a trap that allowed the British breathing space and time to build up intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. More generally, it can b ...

on the IRA, and McKee was criticised for allowing the IRA to become involved in sectarian killings, as well a feud with the Official IRA in October and November 1975 that left eleven people dead.

The "Long War"

Following the end of the ceasefire, the British government introduced a new three-part strategy to deal with the Troubles; the parts became known asUlsterisation

Ulsterisation refers to one part – "primacy of the police" – of a three-part strategy (the other two being "normalisation" and "criminalisation") of the British government during the conflict known as the Troubles.Kevin Kelly, ''The Longest War ...

, normalisation, and criminalisation. Ulsterisation involved increasing the role of the locally recruited RUC and Ulster Defence Regiment

The Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) was an infantry regiment of the British Army established in 1970, with a comparatively short existence ending in 1992. Raised through public appeal, newspaper and television advertisements,Potter p25 their offi ...

(UDR), a part-time element of the British Army, in order to try to contain the conflict inside Northern Ireland and reduce the number of British soldiers recruited from outside of Northern Ireland being killed. Normalisation involved the ending of internment without trial and Special Category Status

In July 1972, William Whitelaw, the Conservative British government's Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, granted Special Category Status (SCS) to all prisoners serving sentences in Northern Ireland for Troubles-related offences. This had bee ...

, the latter had been introduced in 1972 following a hunger strike led by McKee. Criminalisation was designed to alter public perception of the Troubles, from an insurgency requiring a military solution to a criminal problem requiring a law enforcement solution. As result of the withdrawal of Special Category Status, in September 1976 IRA prisoner Kieran Nugent

Kieran Nugent (1958 – 4 May 2000) was an Irish volunteer in the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) and best known for being the first IRA 'blanket man' in the Maze Prison in Northern Ireland. When sentenced to three years for hijacking a bus ...

began the blanket protest

The blanket protest was part of a five-year protest during the Troubles by Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) and Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) prisoners held in the Maze prison (also known as "Long Kesh") in Northern Ireland. The ...

in the Maze Prison

Her Majesty's Prison Maze (previously Long Kesh Detention Centre, and known colloquially as The Maze or H-Blocks) was a prison in Northern Ireland that was used to house alleged paramilitary prisoners during the Troubles from August 1971 to Sept ...

, when hundreds of prisoners refused to wear prison uniforms.

In 1977 the IRA evolved a new strategy which they called the "Long War", which would remain their strategy for the rest of the Troubles. This strategy accepted that their campaign would last many years before being successful, and included increased emphasis on political activity through Sinn Féin. A republican document of the early 1980s states "Both Sinn Féin and the IRA play different but converging roles in the war of national liberation. The Irish Republican Army wages an armed campaign... Sinn Féin maintains the propaganda war and is the public and political voice of the movement". The 1977 edition of the '' Green Book'', an induction and training manual used by the IRA, describes the strategy of the "Long War" in these terms:

# A war of attrition against enemy personnel ritish Armywhich is aimed at causing as many casualties and deaths as possible so as to create a demand from their he British

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

people at home for their withdrawal.

# A bombing campaign aimed at making the enemy's financial interests in our country unprofitable while at the same time curbing long-term investment in our country.

# To make the Six Counties... ungovernable except by colonial military rule.

# To sustain the war and gain support for its ends by National and International propaganda and publicity campaigns.

# By defending the war of liberation by punishing criminals, collaborators and informers

An informant (also called an informer or, as a slang term, a “snitch”) is a person who provides privileged information about a person or organization to an agency. The term is usually used within the law-enforcement world, where informan ...

.

The "Long War" saw the IRA's tactics move away from the large bombing campaigns of the early 1970s, in favour of more attacks on members of the security forces. The IRA's new multi-faceted strategy saw them begin to use armed propaganda

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pro ...

, using the publicity gained from attacks such as the assassination of Lord Mountbatten

Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979) was a British naval officer, colonial administrator and close relative of the British royal family. Mountbatten, who was of German ...

and the Warrenpoint ambush

The Warrenpoint ambush, also known as the Narrow Water ambush, the Warrenpoint massacre or the Narrow Water massacre, was a guerrilla attack by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) on 27 August 1979. The IRA's South Armagh Brigade ambus ...

to focus attention on the nationalist community's rejection of British rule. The IRA aimed to keep Northern Ireland unstable, which would frustrate the British objective of installing a power sharing

Power sharing is a practice in conflict resolution where multiple groups distribute political, military, or economic power among themselves according to agreed rules. It can refer to any formal framework or informal pact that regulates the distri ...

government as a solution to the Troubles.

The prison protest against criminalisation culminated in the 1981 Irish hunger strike, when seven IRA and three

The prison protest against criminalisation culminated in the 1981 Irish hunger strike, when seven IRA and three Irish National Liberation Army

The Irish National Liberation Army (INLA, ga, Arm Saoirse Náisiúnta na hÉireann) is an Irish republican socialist paramilitary group formed on 10 December 1974, during the 30-year period of conflict known as "the Troubles". The group seek ...

members starved themselves to death in pursuit of political status. The hunger strike leader Bobby Sands

Robert Gerard Sands ( ga, Roibeárd Gearóid Ó Seachnasaigh; 9 March 1954 – 5 May 1981) was a member (and leader in the Maze prison) of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) who died on hunger strike while imprisoned at HM Prison Maze ...

and Anti H-Block

Anti H-Block was the political label used in 1981 by supporters of the Irish republican hunger strike who were standing for election in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. "H-Block" was a metonym for the Maze Prison, within whos ...

activist Owen Carron

Owen Gerard Carron (born 9 February 1953) is an Irish republican activist who was Member of Parliament (MP) for Fermanagh and South Tyrone from 1981 to 1983.

Early life

Carron was born in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh. He qualified as a teache ...

were successively elected to the British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, and two other protesting prisoners were elected to Dáil Éireann. The electoral successes led to the IRA's armed campaign being pursued in parallel with increased electoral participation by Sinn Féin. This strategy was known as the "Armalite and ballot box strategy", named after Danny Morrison's speech at the 1981 Sinn Féin ard fheis:

Who here really believes that we can win the war through the ballot box? But will anyone here object if with a ballot paper in this hand and an Armalite in this hand we take power in Ireland?Attacks on high-profile political and military targets remained a priority for the IRA. The

Chelsea Barracks bombing

The Chelsea Barracks bombing was an attack carried out by a London-based Active Service Unit (ASU) of the Provisional IRA on 10 October 1981, using remote-controlled nail bomb. The bomb targeted a bus carrying British Army soldiers just outsid ...

in London in October 1981 killed two civilians and injured twenty-three soldiers; a week later the IRA struck again in London by an assassination attempt on Lieutenant General Steuart Pringle

Lieutenant General Sir Steuart Robert Pringle (21 July 1928 – 18 April 2013) was a Scottish Royal Marines officer who served as Commandant General Royal Marines from 1981 to 1985. He was seriously injured by an IRA car bomb in 1981, in which h ...

, the Commandant General Royal Marines

The Commandant General Royal Marines is the professional head of the Royal Marines. The title has existed since 1943. The role is held by a General who is assisted by a Deputy Commandant General, with the rank of brigadier. This position is not t ...

. Attacks on military targets in England continued with the Hyde Park and Regent's Park bombings

The Hyde Park and Regent's Park bombings were carried out on 20 July 1982 in London, England. Members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) detonated two improvised explosive devices during British military ceremonies in Hyde Park a ...

in July 1982, which killed eleven soldiers and injured over fifty people including civilians. In October 1984 they carried out the Brighton hotel bombing

A Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) assassination attempt against members of the British government took place on 12 October 1984 at the Grand Hotel in Brighton, East Sussex, England, United Kingdom. A long-delay time bomb was plante ...

, an assassination attempt on British prime minister Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

, whom they blamed for the deaths of the ten hunger strikers. The bombing killed five members of the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

attending a party conference including MP Anthony Berry

Sir Anthony George Berry (12 February 1925 – 12 October 1984) was a British Conservative politician. He served as Member of Parliament (MP) for Enfield Southgate and a whip in Margaret Thatcher's government.

Berry served as an MP for nearl ...

, with Thatcher narrowly escaping death. A planned escalation of the England bombing campaign in 1985 was prevented when six IRA volunteers, including Martina Anderson

Martina Anderson (born 16 April 1962) is an Irish former politician from Northern Ireland who served as Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) for Foyle from 2020 to 2021, and previously from 2007 to 2012. A member of Sinn Féin, she served ...

and the Brighton bomber Patrick Magee, were arrested in Glasgow. Plans for a major escalation of the campaign in the late 1980s were cancelled after a ship carrying 150 tonnes of weapons donated by Libya was seized off the coast of France. The plans, modelled on the Tet Offensive

The Tet Offensive was a major escalation and one of the largest military campaigns of the Vietnam War. It was launched on January 30, 1968 by forces of the Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) against the forces o ...

during the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, relied on the element of surprise which was lost when the ship's captain informed French authorities of four earlier shipments of weapons, which allowed the British Army to deploy appropriate countermeasure

A countermeasure is a measure or action taken to counter or offset another one. As a general concept, it implies precision and is any technological or tactical solution or system designed to prevent an undesirable outcome in the process. The fi ...

s. In 1987 the IRA began attacking British military targets in mainland Europe, beginning with the Rheindahlen bombing, which was followed by approximately twenty other gun and bomb attacks aimed at British Armed Forces

The British Armed Forces, also known as His Majesty's Armed Forces, are the military forces responsible for the defence of the United Kingdom, its Overseas Territories and the Crown Dependencies. They also promote the UK's wider interests, s ...

personnel and bases between 1988 and 1990.

Peace process

By the late 1980s the Troubles were at a military and political stalemate, with the IRA able to prevent the British government imposing a settlement but unable to force their objective of Irish reunification. Sinn Féin president Adams was in contact withSocial Democratic and Labour Party

The Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) ( ga, Páirtí Sóisialta Daonlathach an Lucht Oibre) is a social-democratic and Irish nationalist political party in Northern Ireland. The SDLP currently has eight members in the Northern Ireland ...

(SDLP) leader John Hume

John Hume (18 January 19373 August 2020) was an Irish nationalist politician from Northern Ireland, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the recent political history of Ireland, as one of the architects of the Northern Irela ...

and a delegation representing the Irish government, in order to find political alternatives to the IRA's campaign. As a result of the republican leadership appearing interested in peace, British policy shifted when Peter Brooke, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland

A secretary, administrative professional, administrative assistant, executive assistant, administrative officer, administrative support specialist, clerk, military assistant, management assistant, office secretary, or personal assistant is a w ...

, began to engage with them hoping for a political settlement. Backchannel diplomacy between the IRA and British government began in October 1990, with Sinn Féin being given an advance copy of a planned speech by Brooke. The speech was given in London the following month, with Brooke stating that the British government would not give in to violence but offering significant political change if violence stopped, ending his statement by saying:

The British government has no selfish, strategic or economic interest in Northern Ireland: Our role is to help, enable and encourage ... Partition is an acknowledgement of reality, not an assertion of national self-interest.

The IRA responded to Brooke's speech by declaring a three-day ceasefire over Christmas, the first in fifteen years. Afterwards the IRA intensified the bombing campaign in England, planting 36 bombs in 1991 and 57 in 1992, up from 15 in 1990. The

The IRA responded to Brooke's speech by declaring a three-day ceasefire over Christmas, the first in fifteen years. Afterwards the IRA intensified the bombing campaign in England, planting 36 bombs in 1991 and 57 in 1992, up from 15 in 1990. The Baltic Exchange bombing

The Baltic Exchange bombing was an attack by the Provisional IRA on the City of London, Britain's financial centre, on 10 April 1992, the day after the General Election which re-elected John Major from the Conservative Party as Prime Minister. ...

in April 1992 killed three people and caused an estimated £800 million worth of damage, £200 million more than the total damage caused by the Troubles in Northern Ireland up to that point. In December 1992 Patrick Mayhew

Patrick Barnabas Burke Mayhew, Baron Mayhew of Twysden, (11 September 1929 – 25 June 2016) was a British barrister and politician.

Early life

atrick’s father, George Mayhew, was a decorated army officer turned oil executive; his mother, S ...

, who had succeeded Brooke as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, gave a speech directed at the IRA in Coleraine

Coleraine ( ; from ga, Cúil Rathain , 'nook of the ferns'Flanaghan, Deirdre & Laurence; ''Irish Place Names'', page 194. Gill & Macmillan, 2002. ) is a town and civil parish near the mouth of the River Bann in County Londonderry, Northern I ...

, stating that while Irish reunification could be achieved by negotiation, the British government would not give in to violence. The secret talks between the British government and the IRA via intermediaries

An intermediary (or go-between) is a third party that offers intermediation services between two parties, which involves conveying messages between principals in a dispute, preventing direct contact and potential escalation of the issue. In law ...

continued, with the British government arguing the IRA would be more likely to achieve its objective through politics than continued violence. The talks progressed slowly due to continued IRA violence, including the Warrington bombing in March 1993 which killed two children and the Bishopsgate bombing

The Bishopsgate bombing occurred on 24 April 1993, when the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) detonated a powerful truck bomb on Bishopsgate, a major thoroughfare in London's financial district, the City of London. Telephoned warning ...

a month later which killed one person and caused an estimated £1 billion worth of damage. In December 1993 a press conference was held at London's Downing Street

Downing Street is a street in Westminster in London that houses the official residences and offices of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Situated off Whitehall, it is long, and a few minutes' walk ...

by British prime minister John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997, and as Member of Parliament ...

and the Irish Taoiseach Albert Reynolds

Albert Martin Reynolds (3 November 1932 – 21 August 2014) was an Irish Fianna Fáil politician who served as Taoiseach from 1992 to 1994, Leader of Fianna Fáil from 1992 to 1994, Minister for Finance from 1988 to 1991, Minister for Industry ...

. They delivered the Downing Street Declaration

Downing may refer to:

Places

* Downing, Missouri, US, a city

* Downing, Wisconsin, US, a village

* Downing Park (Newburgh, New York), US, a public park

* Downing, Flintshire, Wales

Buildings

* Downing Centre, Sydney, New South Wales, Austral ...

which conceded the right of Irish people to self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

, but with separate referendums in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. In January 1994 The Army Council voted to reject the declaration, while Sinn Féin asked the British government to clarify certain aspects of the declaration. The British government replied saying the declaration spoke for itself, and refused to meet with Sinn Féin unless the IRA called a ceasefire.

On 31 August 1994 the IRA announced a "complete cessation of military operations" on the understanding that Sinn Féin would be included in political talks for a settlement. A new strategy known as "TUAS" was revealed to the IRA's rank-and-file following the ceasefire, described as either "Tactical Use of Armed Struggle" to the Irish republican movement

Irish Republican Movement is a dissident republican vigilante group founded in April 2018. They formed as a splinter group of Óglaigh na hÉireann, after they went on ceasefire in 2018.

See also

* Republican movement (Ireland) The republic ...

or "Totally Unarmed Strategy" to the broader Irish nationalist movement. The strategy involved a coalition including Sinn Féin, the SDLP and the Irish government acting in concert to apply leverage to the British government, with the IRA's armed campaign starting and stopping as necessary, and an option to call off the ceasefire if negotiations failed. The British government refused to admit Sinn Féin to multi-party talks before the IRA decommissioned its weapons, and a standoff began as the IRA refused to disarm before a final peace settlement had been agreed. The IRA regarded themselves as being undefeated and decommissioning as an act of surrender, and stated decommissioning had never been mentioned prior to the ceasefire being declared. In March 1995 Mayhew set out three conditions for Sinn Féin being admitted to multi-party talks. Firstly the IRA had to be willing to agree to "disarm progressively", secondly a scheme for decommissioning had to be agreed, and finally some weapons had to be decommissioned prior to the talks beginning as a confidence building measure

Confidence-building measures (CBMs) or confidence- and security-building measures (CSBMs) are actions taken to reduce fear of attack by both (or more) parties in a situation of conflict. The term is most often used in the context of armed conflict, ...

. The IRA responded with public statements in September calling decommissioning an "unreasonable demand" and a " stalling tactic" by the British government.

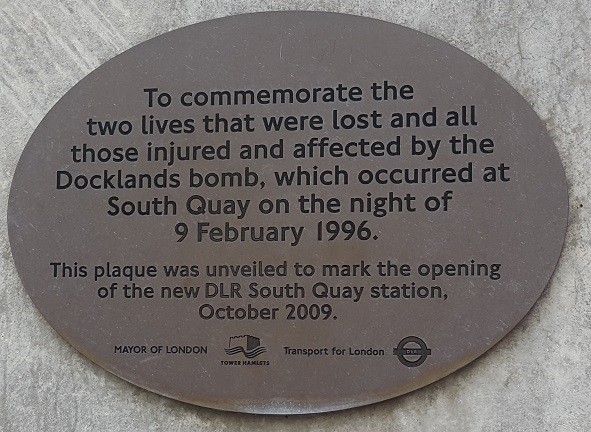

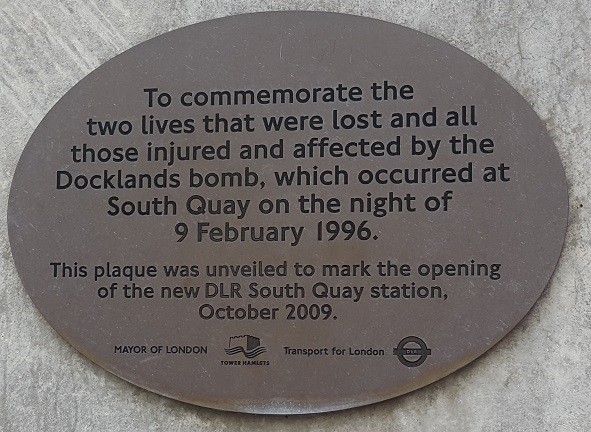

On 9 February 1996 a statement from the Army Council was delivered to the Irish national broadcaster

On 9 February 1996 a statement from the Army Council was delivered to the Irish national broadcaster Raidió Teilifís Éireann

Raidi (; ; also written Ragdi; born August, 1938) is a Tibetan politician of the People's Republic of China. He served as a vice chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress from 2003 to 2008, and the highest ranking Tibeta ...

announcing the end of the ceasefire, and just over 90 minutes later the Docklands bombing

The London Docklands bombing (also known as the South Quay bombing or erroneously referred to as the Canary Wharf bombing) occurred on 9 February 1996, when the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) detonated a powerful truck bomb in South Q ...

killed two people and caused an estimated £100–150 million damage to some of London's more expensive commercial property

Commercial property, also called commercial real estate, investment property or income property, is real estate (buildings or land) intended to generate a profit, either from capital gains or rental income. Commercial property includes office bu ...

. Three weeks later the British and Irish governments issued a joint statement announcing multi-party talks would begin on 10 June, with Sinn Féin excluded unless the IRA called a new ceasefire. The IRA's campaign continued with the Manchester bombing on 15 June, which injured over 200 people and caused an estimated £400 million of damage to the city centre. Attacks were mostly in England apart from the Osnabrück mortar attack

The Osnabrück mortar attack was an improvised mortar attack carried out by a Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) unit based in mainland Europe on 28 June 1996 against the British Army's Quebec Barracks at Osnabrück Garrison near Osnabr� ...

on a British Army base in Germany. The IRA's first attack in Northern Ireland since the end of the ceasefire was not until October 1996, when the Thiepval barracks bombing killed a British soldier. In February 1997 an IRA sniper team killed Lance Bombadier Stephen Restorick, the last British soldier to be killed by the IRA.

Following the May 1997 UK general election Major was replaced as prime minister by Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

of the Labour Party. The new Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Mo Mowlam

Dr Marjorie "Mo" Mowlam (18 September 1949 – 19 August 2005) was a British Labour Party politician. She was the Member of Parliament (MP) for Redcar from 1987 to 2001 and served in the Cabinet as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Minis ...