Provisional Government of Russia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a

at prlib.ru, accessed 12 June 2017

On 12 March (27 February,

On 12 March (27 February,

With the 1917 February Revolution, Tsar Nicholas II's abdication, and the formation of a completely new Russian state, Russia's political spectrum was dramatically altered. The tsarist leadership represented an authoritarian, conservative form of governance. The Kadet Party (see

With the 1917 February Revolution, Tsar Nicholas II's abdication, and the formation of a completely new Russian state, Russia's political spectrum was dramatically altered. The tsarist leadership represented an authoritarian, conservative form of governance. The Kadet Party (see

In August 1917 Russian socialists assembled for a conference on defense, which resulted in a split between the Bolsheviks, who rejected the continuation of the war, and moderate socialists. The Kornilov affair was an attempted military

In August 1917 Russian socialists assembled for a conference on defense, which resulted in a split between the Bolsheviks, who rejected the continuation of the war, and moderate socialists. The Kornilov affair was an attempted military

online

* Thatcher, Ian D. "Historiography of the Russian Provisional Government 1917 in the USSR." ''Twentieth Century Communism'' (2015), Issue 8, p108-132. * Thatcher, Ian D. "Memoirs of the Russian Provisional Government 1917." ''Revolutionary Russia'' 27.1 (2014): 1-21. * Thatcher, Ian D. "The ‘broad centrist’ political parties and the first provisional government, 3 March–5 May 1917." ''Revolutionary Russia'' 33.2 (2020): 197-220. * Wade, Rex A. "The Revolution at One Hundred: Issues and Trends in the English Language Historiography of the Russian Revolution of 1917." ''Journal of Modern Russian History and Historiography'' 9.1 (2016): 9-38.

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a

The Russian Provisional Government ( rus, Временное правительство России, Vremennoye pravitel'stvo Rossii) was a provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

of the Russian Republic

The Russian Republic,. referred to as the Russian Democratic Federal Republic. in the Decree on the system of government of Russia (1918), 1918 Constitution, was a short-lived state (polity), state which controlled, ''de jure'', the territ ...

, announced two days before and established immediately after the abdication of Nicholas II. The intention of the provisional government was the organization of elections to the Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly (Всероссийское Учредительное собрание, Vserossiyskoye Uchreditelnoye sobraniye) was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917. It met fo ...

and its convention. The provisional government, led first by Prince Georgy Lvov

Prince Georgy Yevgenyevich Lvov (7/8 March 1925) was a Russian aristocrat and statesman who served as the first prime minister of republican Russia from 15 March to 20 July 1917. During this time he served as Russia's ''de facto'' head of stat ...

and then by Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; Reforms of Russian orthography, original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months ...

, lasted approximately eight months, and ceased to exist when the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

gained power in the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

in October N.S..html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="ovember, Old Style and New Style dates">N.S.">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="ovember, Old Style and New Style dates">N.S.1917.

According to Harold Whitmore Williams, the history of the eight months during which Russia was ruled by the Provisional Government was the history of the steady and systematic disorganization of the army. For most of the life of the Provisional Government, the status of the monarchy was unresolved. This was finally clarified on 1 September 4 September, N.S. when the Russian Republic

The Russian Republic,. referred to as the Russian Democratic Federal Republic. in the Decree on the system of government of Russia (1918), 1918 Constitution, was a short-lived state (polity), state which controlled, ''de jure'', the territ ...

was proclaimed, in a decree signed by Kerensky as Minister-President and Zarudny as Minister of Justice.The Russian Republic Proclaimedat prlib.ru, accessed 12 June 2017

Overview

On 12 March (27 February,

On 12 March (27 February, Old Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

) - after Prime Minister Nikolai Golitsyn

Prince Nikolai Dmitriyevich Golitsyn (russian: Никола́й Дми́триевич Голи́цын; 12 April 1850 – 2 July 1925) was a Russian aristocrat, monarchist and the last prime minister of Imperial Russia. He was in office from 2 ...

was forced to resign - 24 commissars the Provisional Committee of the State Duma

The Provisional Committee of the State Duma () was a special government body established on March 12, 1917 (27 February O.S.) by the Fourth State Duma deputies at the outbreak of the February Revolution in the same year. It was formed under th ...

were appointed. The Committee was headed by Mikhail Rodzianko

Mikhail Vladimirovich Rodzianko (russian: Михаи́л Влади́мирович Родзя́нко; uk, Михайло Володимирович Родзянко; 21 February 1859, Yekaterinoslav Governorate – 24 January 1924, Beod ...

and suspended the activity of the Fourth State Duma

The State Duma (russian: Госуда́рственная ду́ма, r=Gosudárstvennaja dúma), commonly abbreviated in Russian as Gosduma ( rus, Госду́ма), is the lower house of the Federal Assembly of Russia, while the upper house ...

. He temporarily took formal state power and announced the creation of a new government on 13 March. The Provisional Government was formed on 15 March 1917 (New Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

) by the Provisional Committee in cooperation of the Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

, despite protests of the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

. The government was led first by Prince Georgy Lvov

Prince Georgy Yevgenyevich Lvov (7/8 March 1925) was a Russian aristocrat and statesman who served as the first prime minister of republican Russia from 15 March to 20 July 1917. During this time he served as Russia's ''de facto'' head of stat ...

and then by Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; Reforms of Russian orthography, original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months ...

. It replaced the Council of Ministers of Russia The Russian Council of Ministers is an executive governmental council that brings together the principal officers of the Executive Branch of the Russian government. This includes the chairman of the government and ministers of federal government dep ...

, which presided in the Mariinsky Palace

Mariinsky Palace (), also known as Marie Palace, was the last neoclassical Imperial residence to be constructed in Saint Petersburg. It was built between 1839 and 1844, designed by the court architect Andrei Stackenschneider. It houses the ci ...

.

The Provisional Government was unable to make decisive policy decisions due to political factionalism and a breakdown of state structures. This weakness left the government open to strong challenges from both the right and the left. The Provisional Government's chief adversary on the left was the Petrograd Soviet, a Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

committee then taking over and ruling Russia's most important port city, which tentatively cooperated with the government at first, but then gradually gained control of the Imperial Army, local factories, and the Russian Railway. The period of competition for authority ended in late October 1917, when Bolsheviks routed the ministers of the Provisional Government in the events known as the "October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

", and placed power in the hands of the soviets

Soviet people ( rus, сове́тский наро́д, r=sovyétsky naród), or citizens of the USSR ( rus, гра́ждане СССР, grázhdanye SSSR), was an umbrella demonym for the population of the Soviet Union.

Nationality policy in th ...

, or "workers' councils," which had given their support to the Bolsheviks led by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

and Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

.

The weakness of the Provisional Government is perhaps best reflected in the derisive nickname given to Kerensky: "persuader-in-chief."

Formation

The authority of the Tsar's government began disintegrating on 1 November 1916, whenPavel Milyukov

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov ( rus, Па́вел Никола́евич Милюко́в, p=mʲɪlʲʊˈkof; 31 March 1943) was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the Con ...

attacked the Boris Stürmer

Baron Boris Vladimirovich Shturmer (russian: Бори́с Влади́мирович Штю́рмер) (27 July 1848 – 9 September 1917) was a Russian lawyer, a Master of Ceremonies at the Russian Court, and a district governor. He became a ...

government in the Duma. Stürmer was succeeded by Alexander Trepov

Alexander Fyodorovich Trepov (; 30 September 1862, Kiev – 10 November 1928, Nice) was the Prime Minister of the Russian Empire from 23 November 1916 until 9 January 1917. He was conservative, a monarchist, a member of the Russian Assembly, a ...

and Nikolai Golitsyn

Prince Nikolai Dmitriyevich Golitsyn (russian: Никола́й Дми́триевич Голи́цын; 12 April 1850 – 2 July 1925) was a Russian aristocrat, monarchist and the last prime minister of Imperial Russia. He was in office from 2 ...

, both Prime Ministers for only a few weeks. During the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and somet ...

two rival institutions, the imperial State Duma

The State Duma (russian: Госуда́рственная ду́ма, r=Gosudárstvennaja dúma), commonly abbreviated in Russian as Gosduma ( rus, Госду́ма), is the lower house of the Federal Assembly of Russia, while the upper house ...

and the Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

, both located in the Tauride Palace

Tauride Palace (russian: Таврический дворец, translit=Tavrichesky dvorets) is one of the largest and most historically important palaces in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Construction and early use

Prince Grigory Potemkin of Tauride ...

, competed for power. Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Polan ...

abdicated on 2 March 5 March,

5 (five) is a number, numeral and digit. It is the natural number, and cardinal number, following 4 and preceding 6, and is a prime number. It has attained significance throughout history in part because typical humans have five digits on eac ...

and Milyukov announced the committee's decision to offer the Regency to his brother, Grand Duke Michael, as the next tsar. Grand Duke Michael would accept after the decision of the Russian Constituent Assembly

The All Russian Constituent Assembly (Всероссийское Учредительное собрание, Vserossiyskoye Uchreditelnoye sobraniye) was a constituent assembly convened in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917. It met fo ...

.

He did not want to take the poisoned chalice and deferred acceptance of imperial power the next day. The Provisional Government was designed to set up elections to the Assembly while maintaining essential government services, but its power was effectively limited by the Petrograd Soviet's growing authority.

Public announcement of the formation of the Provisional Government was made. It was published in ''Izvestia

''Izvestia'' ( rus, Известия, p=ɪzˈvʲesʲtʲɪjə, "The News") is a daily broadsheet newspaper in Russia. Founded in 1917, it was a newspaper of record in the Soviet Union until the Soviet Union's dissolution in 1991, and describes ...

'' the day after its formation. The announcement stated the declaration of government

* Full and immediate amnesty on all issues political and religious, including: terrorist acts, military uprisings, and agrarian crimes etc.

* Freedom of word, press, unions, assemblies, and strikes with spread of political freedoms to military servicemen within the restrictions allowed by military-technical conditions.

* Abolition of all hereditary, religious, and national class restrictions.

* Immediate preparations for the convocation on basis of universal, equal, secret, and direct vote for the Constituent Assembly which will determine the form of government and the constitution.

* Replacement of the police with a public militsiya

''Militsiya'' ( rus, милиция, , mʲɪˈlʲitsɨjə) was the name of the police forces in the Soviet Union (until 1991) and in several Eastern Bloc countries (1945–1992), as well as in the non-aligned SFR Yugoslavia (1945–1992). The ...

and its elected chairmanship subordinated to the local authorities.

* Elections to the authorities of local self-government on basis of universal, direct, equal, and secret vote.

* Non-disarmament and non-withdrawal out of Petrograd the military units participating in the revolution movement.

* Under preservation of strict discipline in ranks and performing a military service - elimination of all restrictions for soldiers in the use of public rights granted to all other citizens.

It also said, "The provisional government feels obliged to add that it is not intended to take advantage of military circumstances for any delay in implementing the above reforms and measures."

World recognition

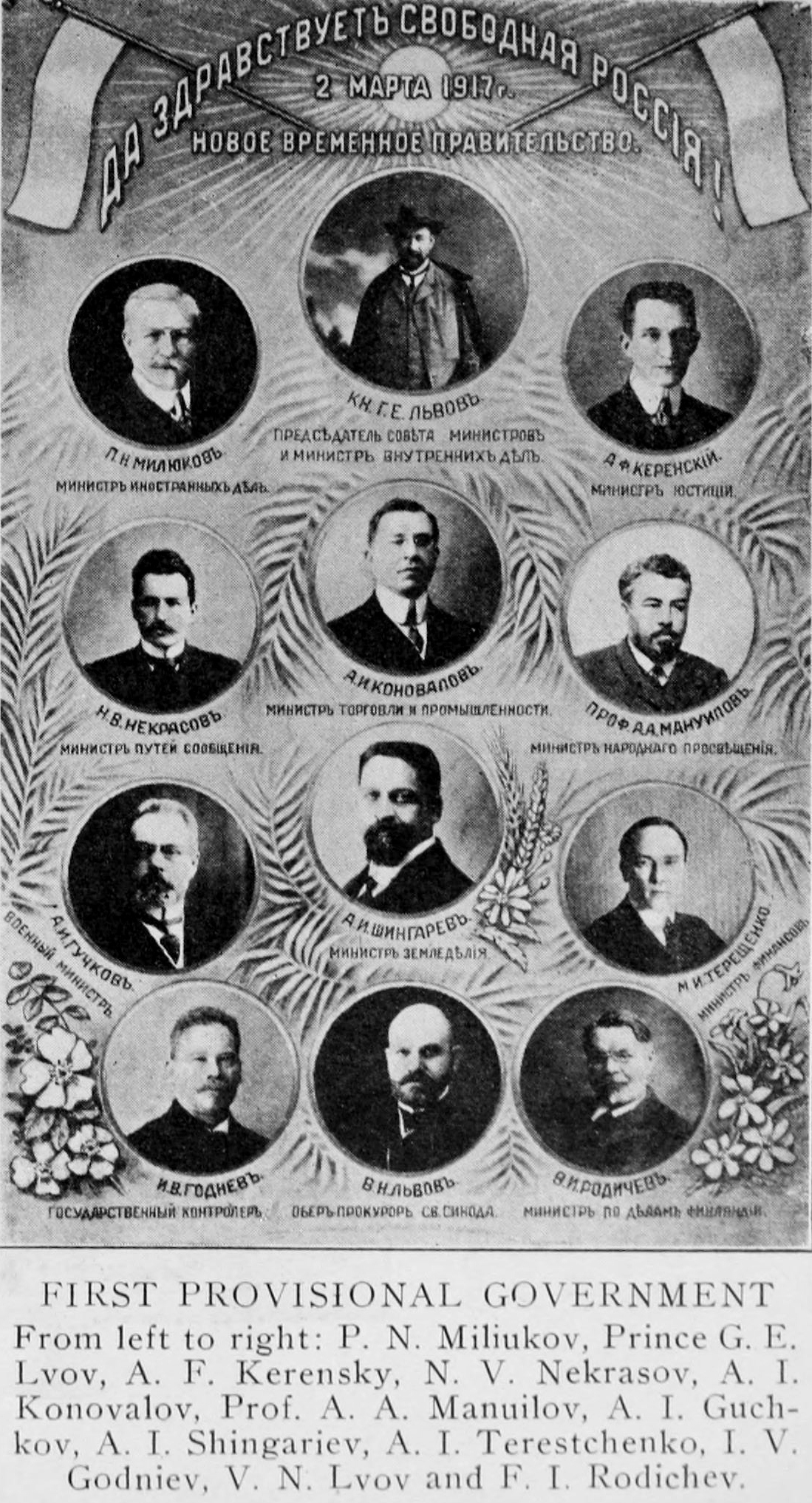

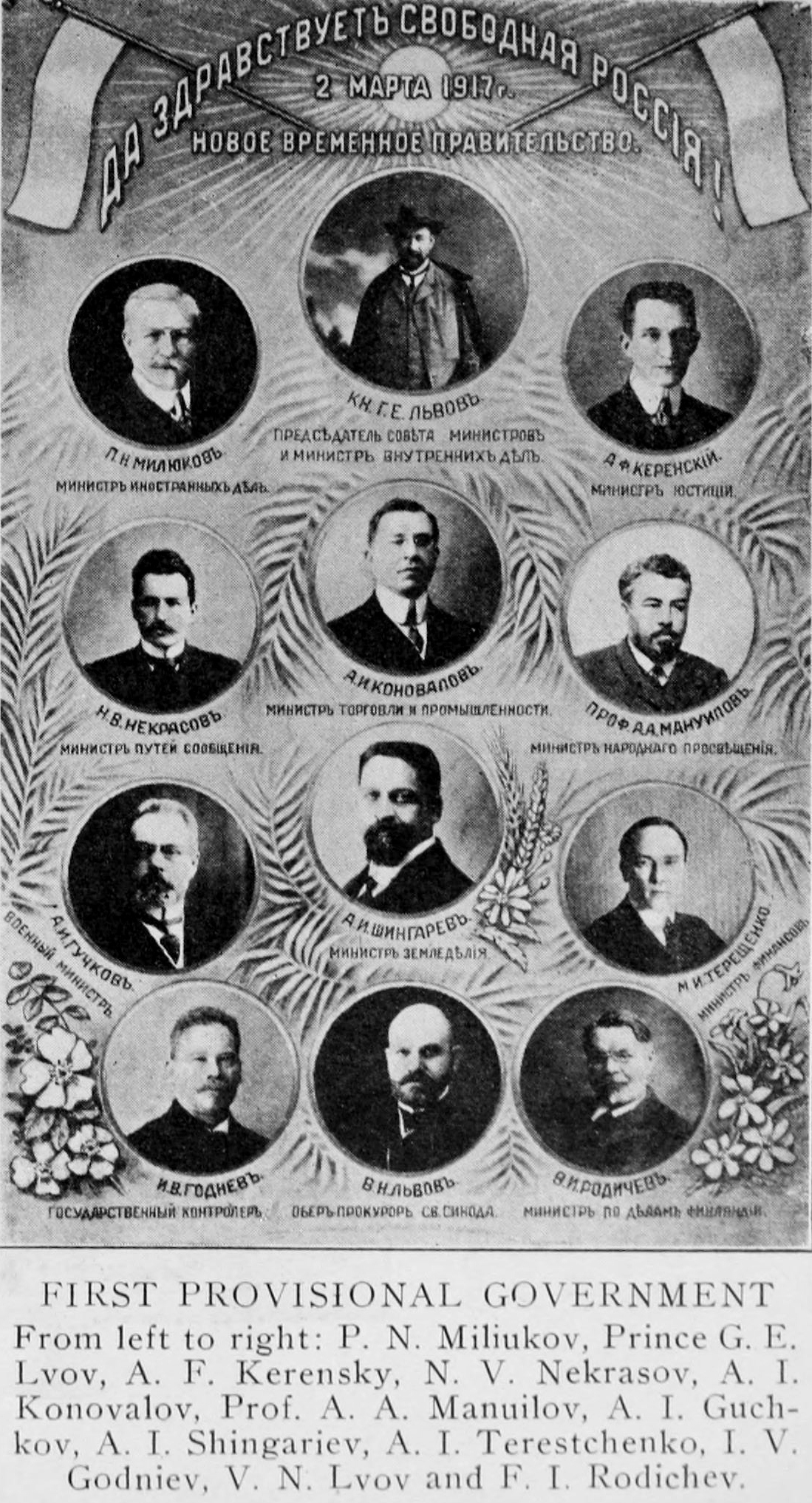

Initial composition

Initial composition of the Provisional Government:April Crisis

During theApril Crisis

The April Crisis, which occurred in Russia throughout April 1917, broke out in response to a series of political and public controversies. Conflict over Russia's foreign policy goals tested the dual power arrangement between the Petrograd Sovie ...

(1917) Ivan Ilyin

Ivan Alexandrovich Ilyin or Il'in (Ива́н Алекса́ндрович Ильи́н, – 21 December 1954) was a Russian jurist, a dogmatic religious and political philosopher, an orator and conservative monarchist. He perceived the Febru ...

agreed with the Kadet

)

, newspaper = ''Rech''

, ideology = ConstitutionalismConstitutional monarchismLiberal democracyParliamentarism Political pluralismSocial liberalism

, position = Centre to centre-left

, international =

, colours ...

Milyukov who staunchly opposed Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

demands for peace at any cost. On 18 April May, 1917 minister of Foreign Affairs Pavel Milyukov

Pavel Nikolayevich Milyukov ( rus, Па́вел Никола́евич Милюко́в, p=mʲɪlʲʊˈkof; 31 March 1943) was a Russian historian and liberal politician. Milyukov was the founder, leader, and the most prominent member of the Con ...

sent a note to the Allied governments, promising to continue the war to 'its glorious conclusion'. On 20–21 April 1917 massive demonstrations of workers and soldiers erupted against the continuation of war. Demonstrations demanded resignation of Milyukov. They were soon met by the counter-demonstrations organised in his support. General Lavr Kornilov

Lavr Georgiyevich Kornilov (russian: Лавр Гео́ргиевич Корни́лов, ; – 13 April 1918) was a Russian military intelligence officer, explorer, and general in the Imperial Russian Army during World War I and the ensuing Russ ...

, commander of the Petrograd military district, wished to suppress the disorders, but premier Georgy Lvov

Prince Georgy Yevgenyevich Lvov (7/8 March 1925) was a Russian aristocrat and statesman who served as the first prime minister of republican Russia from 15 March to 20 July 1917. During this time he served as Russia's ''de facto'' head of stat ...

refused to resort to violence.

The Provisional Government accepted the resignation of Foreign Minister Milyukov and War Minister Guchkov and made a proposal to the Petrograd Soviet to form a coalition government. As a result of negotiations, on 22 April 1917 agreement was reached and 6 socialist ministers joined the cabinet.

During this period the Provisional Government merely reflected the will of the Soviet, where left tendencies (Bolshevism) were gaining ground. The Government, however, influenced by the "bourgeois" ministers, tried to base itself on the right-wing of the Soviet. Socialist ministers, coming under fire from their left-wing Soviet associates, were compelled to pursue a double-faced policy. The Provisional Government was unable to make decisive policy decisions due to political factionalism and a breakdown of state structures.

Kerensky's June Offensive

In the summer of 1917, within the government, the liberals persuaded the socialists that the Provisional Government needed to launch an offensive against Germany. This was as a consequence of several factors: a request from Britain and France to help take the pressure off their forces in the West, avoiding the national humiliation of a defeat, to help put the generals and officers back in control of the armed forces so they could control the revolution and to place them in a better bargaining position with the Germans when peace negotiations started. The government agreed that a ‘successful military offensive’ was required to unite the people and restore morale to the Russian army.Alexander Kerensky

Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, ; Reforms of Russian orthography, original spelling: ( – 11 June 1970) was a Russian lawyer and revolutionary who led the Russian Provisional Government and the short-lived Russian Republic for three months ...

, Minister for War, embarked on a ‘whirlwind tour’ of the Russian forces at the fronts, giving passionate, ‘near-hysterical’, speeches where he called on troops to act heroically, stating ‘we revolutionaries, have the right to death.’ This worked for a time until Kerensky left and the effect on the troops waned.

The June Offensive, which started on 16 June, lasted for just three days before falling apart. During the offensive, the rate of desertion was high and soldiers began to mutiny, with some even killing their commanding officers instead of fighting.

The offensive resulted in the death of thousands of Russian soldiers and great loss of territory. This failed military offensive produced an immediate effect in Petrograd in the form of an armed uprising known as the ‘July Days’. The Provisional Government survived the initial uprising, but their pro-war position meant that moderate socialist government leaders lost their credibility among the soldiers and workers.

July crisis and second coalition government

On July 2 (July 15 N.S.), in response to the government's compromises with Ukrainian nationalists, theKadet

)

, newspaper = ''Rech''

, ideology = ConstitutionalismConstitutional monarchismLiberal democracyParliamentarism Political pluralismSocial liberalism

, position = Centre to centre-left

, international =

, colours ...

members of the cabinet resigned, leaving Prince Lvov's government in disarray. This prompted further urban demonstrations, as workers demanded "all power to the Soviets."

On the morning of July 3 (July 16), the machine-gun regiment voted in favour of an armed demonstration, with it agreed that the demonstrators should march peacefully to the front of the Tauride palace

Tauride Palace (russian: Таврический дворец, translit=Tavrichesky dvorets) is one of the largest and most historically important palaces in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Construction and early use

Prince Grigory Potemkin of Tauride ...

and elect delegates to ‘present their demands to the Executive Committee of the Soviet’.

The following day, July 4 (July 17), around 20,000 armed sailors from the Kronstadt naval base arrived in Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

.2 The mass of soldiers and workers then went to the Bolshevik Headquarters to find Lenin, who addressed the crowd and promised them that, ultimately, all power would go to the Soviets. However, Lenin was rather reluctant about these developments, with his speech uncertain and barely lasting a minute.

As violence escalated in the streets with the mob looting shops, houses, and attacking well-dressed civilians, Cossacks and Kadets stationed atop the buildings of Liteyny Avenue

Liteyny Avenue (russian: Лите́йный проспе́кт, ''Liteyny Prospekt'') is a wide avenue in the Central District of Saint Petersburg, Russia. The avenue runs from Liteyny Bridge to Nevsky Avenue.

The avenue originated in 1738 whe ...

began to fire upon the crowds, causing the marchers to scatter in panic as dozens were killed.

At around 7 pm, soldiers and a group of workers from the Putilov iron plant broke into the palace and, flourishing their rifles, demanded full power to the Soviets.

When Socialist Revolutionary Minister Chernov attempted to calm them down, he was taken outside as a hostage until Trotsky appeared from the Soviet assembly and intervened with a speech praising the “Comrade Kronstadter’s, pride and glory of the Russian revolution”.

Furthermore, the Menshevik Chairman of the Soviet, Chkheidze, spoke to the demonstrators in an ‘imperious tone’, calmly handing their leader a Soviet manifesto, and ordered them to return home or be condemned as traitors to the revolution, to which the crowd quickly dispersed.

The Ministry of Justice released leaflets accusing the Bolsheviks of treason on the charge of inciting armed rebellion with German financial support, and published warrants for the arrest of the party's main leaders. Following this, troops cleared the party's Headquarters in the Kshesinskaya Mansion, and the capital quickly succumbed to anti-Bolshevik hysteria as hundreds of Bolsheviks were arrested and known or suspected Bolsheviks were attacked in the streets by Black Hundreds

The Black Hundred (russian: Чёрная сотня, translit=Chornaya sotnya), also known as the black-hundredists (russian: черносотенцы; chernosotentsy), was a reactionary, monarchist and ultra-nationalist movement in Russia in t ...

elements. The Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

was forced to move from Tauride Palace

Tauride Palace (russian: Таврический дворец, translit=Tavrichesky dvorets) is one of the largest and most historically important palaces in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Construction and early use

Prince Grigory Potemkin of Tauride ...

into the Smolny Institute

The Smolny Institute (russian: Смольный институт, ''Smol'niy institut'') is a Palladian edifice in Saint Petersburg that has played a major part in the history of Russia.

History

The building was commissioned from Giacomo Quar ...

.

Trotsky was captured a few days later and imprisoned, whilst Lenin and Zinoviev went into hiding. Lenin had refused to stand trial for ‘treason’ as he argued that the state was in the hands of a ‘counter-revolutionary military dictatorship’, which was already engaged in a ‘civil war’ against the proletariat. Lenin believed that these events were “an episode in the civil war” and described how “all hopes for a peaceful development of the Russian revolution have vanished for good” when writing a few days after his flight.

These developments left a new crisis in the Provisional Government. Bourgeois ministers, belonging to the Constitutional Democratic Party resigned, and no cabinet could be formed until the end of the month.

The party's political fortunes were poor but were revived after an abortive ‘coup d’etat’ by right-wing elements led by General Kornilov.

Kerensky became the new Prime Minister of the Provisional Government on the 21st of July. Prince Lvov had resigned along with many Bourgeois ministers from the Provisional Government. He had been considered to be closely associated with the soviets, and in a strong leading position.

Finally, on the 24th of July (6 August) 1917, a new coalition cabinet, composed mostly of socialists, was formed with Kerensky at its head.

Second coalition:

Third coalition

From 25 September October, N.S.1917.Legislative policies and problems

With the 1917 February Revolution, Tsar Nicholas II's abdication, and the formation of a completely new Russian state, Russia's political spectrum was dramatically altered. The tsarist leadership represented an authoritarian, conservative form of governance. The Kadet Party (see

With the 1917 February Revolution, Tsar Nicholas II's abdication, and the formation of a completely new Russian state, Russia's political spectrum was dramatically altered. The tsarist leadership represented an authoritarian, conservative form of governance. The Kadet Party (see Constitutional Democratic Party

)

, newspaper = ''Rech''

, ideology = ConstitutionalismConstitutional monarchismLiberal democracyParliamentarism Political pluralismSocial liberalism

, position = Centre to centre-left

, international =

, colours ...

), composed mostly of liberal intellectuals, formed the greatest opposition to the tsarist regime leading up to the February Revolution. The Kadets transformed from an opposition force into a role of established leadership, as the former opposition party held most of the power in the new Provisional Government, which replaced the tsarist regime. The February Revolution was also accompanied by further politicization of the masses. Politicization of working people led to the leftward shift of the political spectrum.

Many urban workers originally supported the socialist Menshevik Party (see Menshevik

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions eme ...

), while some, though a small minority in February, favored the more radical Bolshevik Party (see Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

). The Mensheviks often supported the actions of the Provisional Government and believed that the existence of such a government was a necessary step to achieve Communism. On the other hand, the Bolsheviks violently opposed the Provisional Government and desired a more rapid transition to Communism. In the countryside, political ideology also shifted leftward, with many peasants supporting the Socialist Revolutionary Party (see Socialist-Revolutionary Party

The Socialist Revolutionary Party, or the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (the SRs, , or Esers, russian: эсеры, translit=esery, label=none; russian: Партия социалистов-революционеров, ), was a major politi ...

). The SRs advocated a form of agrarian socialism and land policy that the peasantry overwhelmingly supported. For the most part, urban workers supported the Mensheviks and Bolsheviks (with greater numbers supporting the Bolsheviks as 1917 progressed), while the peasants supported the Socialist Revolutionaries. The rapid development and popularity of these leftist parties turned moderate-liberal parties, such as the Kadets, into "new conservatives." The Provisional Government was mostly composed of "new conservatives," and the new government faced tremendous opposition from the left.

Opposition was most obvious with the development and dominance of the Petrograd Soviet

The Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies (russian: Петроградский совет рабочих и солдатских депутатов, ''Petrogradskiy soviet rabochikh i soldatskikh deputatov'') was a city council of P ...

, which represented the socialist views of leftist parties. A dual power structure quickly arose consisting of the Provisional Government and the Petrograd Soviet. While the Provisional Government retained the formal authority to rule over Russia, the Petrograd Soviet maintained actual power. With its control over the army and the railroads, the Petrograd Soviet had the means to enforce policies. The Provisional Government lacked the ability to administer its policies. In fact, local soviets, political organizations mostly of socialists, often maintained discretion when deciding whether or not to implement the Provisional Government's laws.

Despite its short reign of power and implementation shortcomings, the Provisional Government passed very progressive legislation. The policies enacted by this moderate government (by 1917 Russian standards) represented arguably the most liberal legislation in Europe at the time. The independence of Church from state, the emphasis on rural self-governance, and the affirmation of fundamental civil rights (such as freedom of speech, press, and assembly) that the tsarist government had periodically restricted shows the progressivism of the Provisional Government. Other policies included the abolition of capital punishment and economic redistribution in the countryside. The Provisional Government also granted more freedoms to previously suppressed regions of the Russian Empire. Poland was granted independence and Lithuania and Ukraine became more autonomous.

The main obstacle and problem of the Provisional Government was its inability to enforce and administer legislative policies. Foreign policy was the one area in which the Provisional Government was able to exercise its discretion to a great extent. However, the continuation of aggressive foreign policy (for example, the Kerensky Offensive) increased opposition to the government. Domestically, the Provisional Government's weaknesses were blatant. The dual power structure was in fact dominated by one side, the Petrograd Soviet. Minister of War Alexander Guchkov stated that "We (the Provisional Government) do not have authority, but only the appearance of authority; the real power lies with the Soviet". Severe limitations existed on the Provisional Government's ability to rule.

While it was true that the Provisional Government lacked enforcement ability, prominent members within the Government encouraged bottom-up rule. Politicians such as Prime Minister Georgy Lvov

Prince Georgy Yevgenyevich Lvov (7/8 March 1925) was a Russian aristocrat and statesman who served as the first prime minister of republican Russia from 15 March to 20 July 1917. During this time he served as Russia's ''de facto'' head of stat ...

favored devolution of power to decentralized organizations. The Provisional Government did not desire the complete decentralization of power, but certain members definitely advocated more political participation by the masses in the form of grassroots mobilization.

Democratization

The rise of local organizations, such as trade unions and rural institutions, and the devolution of power within Russian government gave rise to democratization. It is difficult to say that the Provisional Government desired the rise of these powerful, local institutions. As stated in the previous section, some politicians within the Provisional Government advocated the rise of these institutions. Local government bodies had discretionary authority when deciding which Provisional Government laws to implement. For example, institutions that held power in rural areas were quick to implement national laws regarding the peasantry's use of idle land. Real enforcement power was in the hands of these local institutions and the soviets. Russian historian W.E. Mosse points out, this time period represented "the only time in modern Russian history when the Russian people were able to play a significant part in the shaping of their destinies". While this quote romanticizes Russian society under the Provisional Government, the quote nonetheless shows that important democratic institutions were prominent in 1917 Russia. Special interest groups also developed throughout 1917. Special interest groups play a large role in every society deemed "democratic" today, and such was the case of Russia in 1917. Many on the far left would argue that the presence of special interest groups represent a form of bourgeois democracy, in which the interests of an elite few are represented to a greater extent than the working masses. The rise of special interest organizations gave people the means to mobilize and play a role in the democratic process. While groups such as trade unions formed to represent the needs of the working classes, professional organizations were also prominent. Professional organizations quickly developed a political side to represent member's interests. The political involvement of these groups represents a form of democratic participation as the government listened to such groups when formulating policy. Such interest groups played a negligible role in politics before February 1917 and after October 1917. While professional special interest groups were on the rise, so too were worker organizations, especially in the cities. Beyond the formation of trade unions, factory committees of workers rapidly developed on the plant level of industrial centers. The factory committees represented the most radical viewpoints of the time period. The Bolsheviks gained their popularity within these institutions. Nonetheless, these committees represented the most democratic element of 1917 Russia. However, this form of democracy differed from and went beyond the political democracy advocated by the liberal intellectual elites and moderate socialists of the Provisional Government. Workers established economic democracy, as employees gained managerial power and direct control over their workplace. Worker self-management became a common practice throughout industrial enterprises. As workers became more militant and gained more economic power, they supported the radical Bolshevik party and lifted the Bolsheviks into power in October 1917.Kornilov affair and declaration of Republic

In August 1917 Russian socialists assembled for a conference on defense, which resulted in a split between the Bolsheviks, who rejected the continuation of the war, and moderate socialists. The Kornilov affair was an attempted military

In August 1917 Russian socialists assembled for a conference on defense, which resulted in a split between the Bolsheviks, who rejected the continuation of the war, and moderate socialists. The Kornilov affair was an attempted military coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

by the then commander-in-chief of the Russian army, General Lavr Kornilov

Lavr Georgiyevich Kornilov (russian: Лавр Гео́ргиевич Корни́лов, ; – 13 April 1918) was a Russian military intelligence officer, explorer, and general in the Imperial Russian Army during World War I and the ensuing Russ ...

, in September 1917 (August old style). Due to the extreme weakness of the government at this point, there was talk among the elites of bolstering its power by including Kornilov as a military dictator on the side of Kerensky. The extent to which this deal had indeed been accepted by all parties is still unclear. What is clear, however, is that when Kornilov's troops approached Petrograd, Kerensky branded them as counter-revolutionaries and demanded their arrest. This move can be seen as an attempt to bolster his own power by making him a defender of the revolution against a Napoleon-type figure. However, it had terrible consequences, as Kerensky's move was seen in the army as a betrayal of Kornilov, making them finally disloyal to the Provisional Government. Furthermore, as Kornilov's troops were arrested by the now armed Red Guard, it was the Soviet that was seen to have saved the country from military dictatorship. In order to defend himself and Petrograd, he provided the Bolsheviks with arms as he had little support from the army. When Kornilov did not attack Kerensky, the Bolsheviks did not return their weapons, making them a greater concern to Kerensky and the Provisional Government.

Thus far, the status of the monarchy had been unresolved. This was clarified on 1 September 4 September, N.S. when the Russian Republic

The Russian Republic,. referred to as the Russian Democratic Federal Republic. in the Decree on the system of government of Russia (1918), 1918 Constitution, was a short-lived state (polity), state which controlled, ''de jure'', the territ ...

(, ') was proclaimed, in a decree signed by Kerensky as Minister-President and Zarudny as Minister of Justice.

The Decree read as follows:

On 12 September 5, N.San All-Russian Democratic Conference was convened, and its presidium decided to create a Pre-Parliament and a Special Constituent Assembly, which was to elaborate the future Constitution of Russia. This Constitutional Assembly was to be chaired by Professor N. I. Lazarev and the historian V. M. Gessen. The Provisional Government was expected to continue to administer Russia until the Constituent Assembly had determined the future form of government. On 16 September 1917, the Duma

A duma (russian: дума) is a Russian assembly with advisory or legislative functions.

The term ''boyar duma'' is used to refer to advisory councils in Russia from the 10th to 17th centuries. Starting in the 18th century, city dumas were for ...

was dissolved by the newly created Directorate.

October Revolution

On October 24, Kerensky accused the Bolsheviks of treason... After the Bolshevik walkout, some of the remaining delegates continued to stress that ending the war as soon as possible was beneficial to the nation. On 24–26 OctoberRed Guard

Red Guards () were a mass student-led paramilitary social movement mobilized and guided by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 through 1967, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes According to a Red Guard le ...

forces under the leadership of Bolshevik commanders launched their final attack on the ineffectual Provisional Government. Most government offices were occupied and controlled by Bolshevik soldiers on the 25th; the last holdout of the Provisional Ministers, the Tsar's Winter Palace

The Winter Palace ( rus, Зимний дворец, Zimnij dvorets, p=ˈzʲimnʲɪj dvɐˈrʲɛts) is a palace in Saint Petersburg that served as the official residence of the Emperor of all the Russias, Russian Emperor from 1732 to 1917. The p ...

on the Neva River bank, was captured on the 26th. Kerensky escaped the Winter Palace raid and fled to Pskov

Pskov ( rus, Псков, a=pskov-ru.ogg, p=pskof; see also names in other languages) is a city in northwestern Russia and the administrative center of Pskov Oblast, located about east of the Estonian border, on the Velikaya River. Population ...

, where he rallied some loyal troops for an attempt to retake the capital. His troops managed to capture Tsarskoe Selo

Tsarskoye Selo ( rus, Ца́рское Село́, p=ˈtsarskəɪ sʲɪˈlo, a=Ru_Tsarskoye_Selo.ogg, "Tsar's Village") was the town containing a former residence of the Russian imperial family and visiting nobility, located south from the c ...

but were beaten the next day at Pulkovo Pulkovo may refer to:

*Pulkovo Heights marking the southern limit of Saint Petersburg, Russia

*Pulkovo Airport serving Saint Petersburg, Russia

*Pulkovo Aviation Enterprise

Pulkovo Federal State Unified Aviation Service Company (ФГУАП “� ...

. Kerensky spent the next few weeks in hiding before fleeing the country. He went into exile in France and eventually emigrated to the United States.

The Bolsheviks then replaced the government with their own. The ''Little Council'' (or ''Underground Provisional Government'') met at the house of Sofia Panina

Countess Sofia Vladimirovna Panina (Russian: Софья Владимировна Панина; 23 August 1871 – 16 June 1956) was Vice Minister of State Welfare and Vice Minister of Education in the Provisional Government following the Russian F ...

briefly in an attempt to resist the Bolsheviks. However, this initiative ended on 28 November with the arrest of Panina, Fyodor Kokoshkin

Fyodor Fyodorovich Kokoshkin russian: Фёдор Фёдорович Кокошкин; 1 May 1775, Moscow, Russian Empire — 21 September 1838, Moscow) was a Russian dramatist and playwright, Moscow government official and theatre entrepreneur, th ...

, Andrei Ivanovich Shingarev

Andrei Ivanovich Shingarev or Shingaryov (russian: Андре́й Ива́нович Шингарёв) (August 18, 1869 – January 20, 1918) was a Russian doctor, publicist and politician. He was a Duma deputy and one of the leaders of the Co ...

and Prince Pavel Dolgorukov

Prince Pavel Dmitrievich Dolgorukov (russian: Князь Па́вел Дми́триевич Долгору́ков, tr. ; 1866, Tsarskoye Selo – June 9, 1927) was a Russian landowner and aristocrat who was executed by the Bolsheviks in 19 ...

, then Panina being the subject of a political trial A political trial is a criminal trial with political implications. When the trial is carried out without the minimum guarantees of the rule of law, the political trial is the expression of a totalitarian or authoritarian system, where the administra ...

.

Some academics, such as Pavel Osinsky, argue that the October Revolution was as much a function of the failures of the Provisional Government as it was of the strength of the Bolsheviks. Osinsky described this as "socialism by default" as opposed to "socialism by design."

Riasanovsky argued that the Provisional Government made perhaps its "worst mistake" by not holding elections to the Constituent Assembly soon enough. They wasted time fine-tuning details of the election law, while Russia slipped further into anarchy and economic chaos. By the time the Assembly finally met, Riasanovsky noted, "the Bolsheviks had already gained control of Russia."

See also

*Diplomatic history of World War I

The diplomatic history of World War I covers the non-military interactions among the major players during World War I. For the domestic histories of participants see home front during World War I. For a longer-term perspective see international rel ...

Footnotes

Further reading

* * Acton, Edward, et al. eds. ''Critical companion to the Russian Revolution, 1914-1921'' (Indiana UP, 1997). * Hickey, Michael C. "The Provisional Government and Local Administration in Smolensk in 1917." ''Journal of Modern Russian History and Historiography'' 9.1 (2016): 251–274. * Lipatova, Nadezhda V. "On the Verge of the Collapse of Empire: Images of Alexander Kerensky and Mikhail Gorbachev." ''Europe-Asia Studies'' 65.2 (2013): 264–289. * Orlovsky, Daniel. "Corporatism or democracy: the Russian Provisional Government of 1917." ''The Soviet and Post-Soviet Review'' 24.1 (1997): 15–25. * Thatcher, Ian D. "Post-Soviet Russian Historians and the Russian Provisional Government of 1917." ''Slavonic & East European Review'' 93.2 (2015): 315–337online

* Thatcher, Ian D. "Historiography of the Russian Provisional Government 1917 in the USSR." ''Twentieth Century Communism'' (2015), Issue 8, p108-132. * Thatcher, Ian D. "Memoirs of the Russian Provisional Government 1917." ''Revolutionary Russia'' 27.1 (2014): 1-21. * Thatcher, Ian D. "The ‘broad centrist’ political parties and the first provisional government, 3 March–5 May 1917." ''Revolutionary Russia'' 33.2 (2020): 197-220. * Wade, Rex A. "The Revolution at One Hundred: Issues and Trends in the English Language Historiography of the Russian Revolution of 1917." ''Journal of Modern Russian History and Historiography'' 9.1 (2016): 9-38.

Primary sources

* Browder, Robert P. and Alexander F. Kerensky, eds. ''The Russian Provisional Government 1917'' (3 vols, Stanford UP, 1961). {{Authority control Post–Russian Empire states Provisional governments of the Russian Civil War 1917 disestablishments in Russia Anti-communism in Russia Cabinets established in 1917 Russian Empire in World War I Russian governments Russian Revolution Former countries