Provincetown, Massachusetts on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Provincetown is a

Following the American Revolution, Provincetown grew rapidly as a fishing and whaling center. The population was bolstered by numerous Portuguese sailors, many of whom were from the Azores, and settled in Provincetown after being hired to work on US ships.

By the 1890s, Provincetown was booming and began to develop a resident population of writers and artists, as well as a summer tourist industry. After the 1898 Portland Gale severely damaged the town's fishing industry, members of the town's art community took over many of the abandoned buildings. By the early decades of the 20th century, the town had acquired an international reputation for its artistic and literary productions. The Provincetown Players was an important experimental theatre company formed during this period. Many of its members lived during other parts of the year in Greenwich Village in New York, and intellectual and artistic connections were woven between the places. In 1898 Charles Webster Hawthorne opened the Cape Cod School of Art, said to be the first outdoor school for figure painting, in Provincetown. Film of his class from 1916 has been preserved.

The town includes eight buildings and two historic districts on the

Following the American Revolution, Provincetown grew rapidly as a fishing and whaling center. The population was bolstered by numerous Portuguese sailors, many of whom were from the Azores, and settled in Provincetown after being hired to work on US ships.

By the 1890s, Provincetown was booming and began to develop a resident population of writers and artists, as well as a summer tourist industry. After the 1898 Portland Gale severely damaged the town's fishing industry, members of the town's art community took over many of the abandoned buildings. By the early decades of the 20th century, the town had acquired an international reputation for its artistic and literary productions. The Provincetown Players was an important experimental theatre company formed during this period. Many of its members lived during other parts of the year in Greenwich Village in New York, and intellectual and artistic connections were woven between the places. In 1898 Charles Webster Hawthorne opened the Cape Cod School of Art, said to be the first outdoor school for figure painting, in Provincetown. Film of his class from 1916 has been preserved.

The town includes eight buildings and two historic districts on the

For nearly all of Provincetown's recorded history, life has revolved around the waterfront − especially the waterfront on its southern shore − which offers a naturally deep harbor with easy and safe boat access, plus natural protection from the wind and waves. An additional element of Provincetown's geography tremendously influenced the manner in which the town evolved: the town was physically isolated, being at the hard-to-reach tip of a long, narrow

For nearly all of Provincetown's recorded history, life has revolved around the waterfront − especially the waterfront on its southern shore − which offers a naturally deep harbor with easy and safe boat access, plus natural protection from the wind and waves. An additional element of Provincetown's geography tremendously influenced the manner in which the town evolved: the town was physically isolated, being at the hard-to-reach tip of a long, narrow

New England town

The town is the basic unit of Local government in the United States, local government and local division of state authority in the six New England states. Most other U.S. states lack a direct counterpart to the New England town. New England towns ...

located at the extreme tip of Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mon ...

in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, in the United States. A small coastal resort town with a year-round population of 3,664 as of the 2020 United States Census, Provincetown has a summer population as high as 60,000. Often called "P-town" or "P'town", the locale is known for its beaches, harbor, artists, tourist industry, and as a popular vacation destination for the LGBT+ community.

History

At the time of European encounter, the area was long settled by the historic Nauset tribe, who had a settlement known as "Meeshawn". They spoke Massachusett, a Southern New England Algonquian language dialect that they shared in common with their closely related neighbors, the Wampanoag. On 15 May 1602, having made landfall from the west and believing it to be an island, Bartholomew Gosnold initially named this area "Shoal Hope". Later that day, after catching a "great store of codfish", he chose instead to name this outermost tip of land "Cape Cod". Notably, that name referred specifically to the area of modern-day Provincetown; it wasn't until much later that that name was reused to designate the entire region now known asCape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mon ...

.

On 9 November 1620, the Pilgrims aboard the '' Mayflower'' sighted Cape Cod while en route to the Colony of Virginia. After two days of failed attempts to sail south against the strong winter seas, they returned to the safety of the harbor, known today as Provincetown Harbor, and set anchor. It was here that the Mayflower Compact

The Mayflower Compact, originally titled Agreement Between the Settlers of New Plymouth, was the first governing document of Plymouth Colony. It was written by the men aboard the ''Mayflower,'' consisting of separatist Puritans, adventurers, an ...

was drawn up and signed. They agreed to settle and build a self-governing community, and came ashore in the West End.

Though the Pilgrims chose to settle across the bay in Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

, Cape Cod enjoyed an early reputation for its valuable fishing grounds, and for its harbor: a naturally deep, protected basin that was considered the best along the coast. In 1654, the Governor of the Plymouth Colony purchased this land from the Chief of the Nausets, for a selling price of two brass kettles, six coats, 12 hoes, 12 axes, 12 knives and a box.

That land, which spanned from East Harbor (formerly, Pilgrim Lake)—near the present-day border between Provincetown and Truro—to Long Point, was kept for the benefit of Plymouth Colony, which began leasing fishing rights to roving fishermen. The collected fees were used to defray the costs of schools and other projects throughout the colony. In 1678, the fishing grounds were opened up to allow the inclusion of fishermen from the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

.

In 1692, a new Royal Charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

combined the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies into the Province of Massachusetts Bay. "Cape Cod" was thus officially renamed the "Province Lands".

The first record of a municipal government with jurisdiction over the Province Lands was in 1714, with an Act that declared it the "Precinct of Cape Cod", annexed under control of Truro.

On 14 June 1727, after harboring ships for more than a century, the Precinct of Cape Cod was incorporated as a township. The name chosen by its inhabitants was "Herringtown", which was rejected by the Massachusetts General Court in favor of "Provincetown". The act of incorporation provided that inhabitants of Provincetown could be landholders, but not landowners. They received a quit claim to their property, but the Province retained the title. The land was to be used as it had been from the beginning of the colony—a place for the making of fish. All resources, including the trees, could be used for that purpose. In 1893 the Massachusetts General Court changed the Town's charter, giving the townspeople deeds to the properties they held, while still reserving unoccupied areas.

The population of Provincetown remained small through most of the 18th century.

The town was affected by the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

the same way most of Cape Cod was: the effective British blockade shut down most fish production and shipping and the town dwindled. It was, by happenstance, the location of the wreck of British warship at the Peaked Hill Bars off the Atlantic Coast of Provincetown in 1778.

Following the American Revolution, Provincetown grew rapidly as a fishing and whaling center. The population was bolstered by numerous Portuguese sailors, many of whom were from the Azores, and settled in Provincetown after being hired to work on US ships.

By the 1890s, Provincetown was booming and began to develop a resident population of writers and artists, as well as a summer tourist industry. After the 1898 Portland Gale severely damaged the town's fishing industry, members of the town's art community took over many of the abandoned buildings. By the early decades of the 20th century, the town had acquired an international reputation for its artistic and literary productions. The Provincetown Players was an important experimental theatre company formed during this period. Many of its members lived during other parts of the year in Greenwich Village in New York, and intellectual and artistic connections were woven between the places. In 1898 Charles Webster Hawthorne opened the Cape Cod School of Art, said to be the first outdoor school for figure painting, in Provincetown. Film of his class from 1916 has been preserved.

The town includes eight buildings and two historic districts on the

Following the American Revolution, Provincetown grew rapidly as a fishing and whaling center. The population was bolstered by numerous Portuguese sailors, many of whom were from the Azores, and settled in Provincetown after being hired to work on US ships.

By the 1890s, Provincetown was booming and began to develop a resident population of writers and artists, as well as a summer tourist industry. After the 1898 Portland Gale severely damaged the town's fishing industry, members of the town's art community took over many of the abandoned buildings. By the early decades of the 20th century, the town had acquired an international reputation for its artistic and literary productions. The Provincetown Players was an important experimental theatre company formed during this period. Many of its members lived during other parts of the year in Greenwich Village in New York, and intellectual and artistic connections were woven between the places. In 1898 Charles Webster Hawthorne opened the Cape Cod School of Art, said to be the first outdoor school for figure painting, in Provincetown. Film of his class from 1916 has been preserved.

The town includes eight buildings and two historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artist ...

: Provincetown Historic District and Dune Shacks of Peaked Hill Bars Historic District.

In the mid-1960s, Provincetown saw population growth. The town's rural character appealed to the hippies

A hippie, also spelled hippy, especially in British English, is someone associated with the counterculture of the 1960s, originally a youth movement that began in the United States during the mid-1960s and spread to different countries around ...

of the era; property was relatively cheap and rents were correspondingly low, especially during the winter. Many of those who came stayed and raised families. Commercial Street, where most of the town's businesses are located, gained numerous cafés, leather shops, and head shops.

By the 1970s, Provincetown had a significant gay population, especially during the summer tourist season, when restaurants, bars and small shops serving the tourist trade were open. There had been a gay presence in Provincetown as early as the start of the 20th century as the artists' colony developed, along with experimental theatre. Drag queens could be seen in performance as early as the 1940s in Provincetown. In 1978 the Provincetown Business Guild (PBG) was formed to promote gay tourism. Today more than 200 businesses belong to the PBG and Provincetown is perhaps the best-known gay summer resort on the East Coast. The 2010 US Census revealed Provincetown to have the highest rate of same-sex couples in the country, at 163.1 per 1000 households.

Since the 1990s, property prices have risen significantly, causing some residents economic hardship. The housing bust of 2005 - 2012 caused property values in and around town to fall by 10 percent or more in less than a year. This did not slow down the town's economy, however. Provincetown's tourist season has expanded, and the town has created festivals and week-long events throughout the year. The most established are in the summer: the Portuguese Festival, Bear Week, and PBG's Carnival Week.

In 2017, a memorial was dedicated to those who lost their lives to AIDS.

Historic transportation

For nearly all of Provincetown's recorded history, life has revolved around the waterfront − especially the waterfront on its southern shore − which offers a naturally deep harbor with easy and safe boat access, plus natural protection from the wind and waves. An additional element of Provincetown's geography tremendously influenced the manner in which the town evolved: the town was physically isolated, being at the hard-to-reach tip of a long, narrow

For nearly all of Provincetown's recorded history, life has revolved around the waterfront − especially the waterfront on its southern shore − which offers a naturally deep harbor with easy and safe boat access, plus natural protection from the wind and waves. An additional element of Provincetown's geography tremendously influenced the manner in which the town evolved: the town was physically isolated, being at the hard-to-reach tip of a long, narrow peninsula

A peninsula (; ) is a landform that extends from a mainland and is surrounded by water on most, but not all of its borders. A peninsula is also sometimes defined as a piece of land bordered by water on three of its sides. Peninsulas exist on all ...

.

The East Harbor, which provided the most protected mooring place in Provincetown, had a inlet from Provincetown Harbor, and effectively blocked off access to Provincetown by land. Until the late 19th century, no road led to Provincetown – the only land route connecting the village to points back toward the mainland was along a thin stretch of beach along the shore to the north (known locally as the "backshore"). A wooden bridge was erected over the East Harbor in 1854, only to be destroyed by a winter storm and ice two years later. Although the bridge was replaced the following year, any traveler who crossed it still needed to traverse several miles over sand routes, which, together with the backshore route, was occasionally washed out by storms. This made Provincetown very much like an island. Its residents relied almost entirely upon its harbor for its communication, travel, and commerce needs.

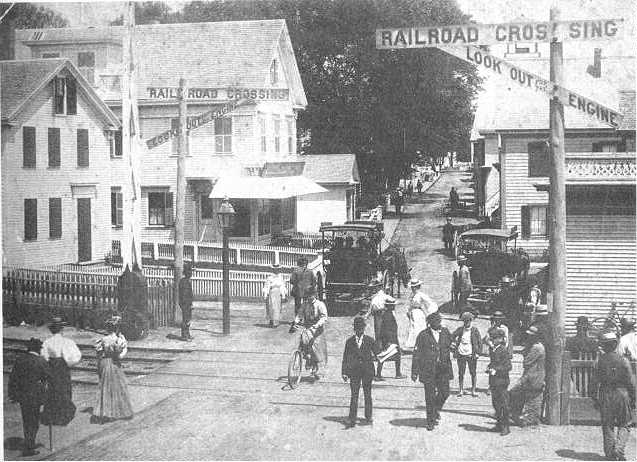

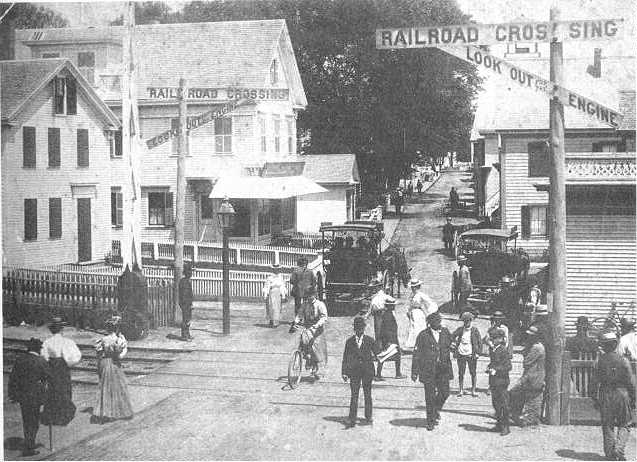

That changed in 1868, when the mouth of the East Harbor was diked to enable the laying of track for the arrival of the railroad. The railroad was completed, to great fanfare, in 1873; and the wooden bridge and sand road was finally replaced by a formal roadway in 1877. The railroad terminated at Railroad Wharf, known today as MacMillan Pier. It provided an easy means for fishermen to offload their vessels and ship their catch to the cities by rail.

The railroad was not the only late arrival to Provincetown. Even roads ''within'' the town were slow to be constructed:

The town's internal road layout reflects the historic importance of the waterfront, the key to communication and commerce with the outside world. As the town grew, it organically expanded along the harborfront. The main "thoroughfare" was the hard-packed beach, where all commerce and socializing took place. Early deeds refer to a "Town Rode", which was little more than a footpath that ran behind the houses. In 1835, County Commissioners turned that into "Front Street", now known as Commercial Street. "Back Street" ran parallel to Front Street, but was set back from the harbor − today it is known as Bradford Street.

Geography

Provincetown is located at the very tip ofCape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mon ...

, encompassing a total area of − 55% of that, or , is land area, and the remaining water area. Surrounded by water in every direction except due east, the town has