Protofeminist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Protofeminism is a concept that anticipates modern

At the beginning of the renaissance, women's sole role and social value was held to be reproduction.

This gender role defined a woman's main identity and purpose in life.

At the beginning of the renaissance, women's sole role and social value was held to be reproduction.

This gender role defined a woman's main identity and purpose in life.

Juliana, better known as the

Juliana, better known as the

Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz was a nun in colonial

Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz was a nun in colonial

died "for their implicit or explicit challenge to the patriarchal order". In France and England, feminist ideas were attributes of

In France and England, feminist ideas were attributes of

feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

in eras when the feminist concept as such was still unknown. This refers particularly to times before the 20th century, although the precise usage is disputed, as 18th-century feminism

The history of feminism comprises the narratives (chronological or thematic) of the movements and ideologies which have aimed at equal rights for women. While feminists around the world have differed in causes, goals, and intentions depending ...

and 19th-century feminism

The history of feminism comprises the narratives (chronological or thematic) of the movements and ideologies which have aimed at equal rights for women. While feminists around the world have differed in causes, goals, and intentions depending ...

are often subsumed into "feminism". The usefulness of the term ''protofeminist'' has been questioned by some modern scholars, as has the term ''postfeminist''.

History

Ancient Greece and Rome

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

, according to Elaine Hoffman Baruch, " rguedfor the total political and sexual equality of women, advocating that they be members of his highest class... those who rule and fight." Book five of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

's '' The Republic'' discusses the role of women:

Are dogs divided into hes and shes, or do they both share equally in hunting and in keeping watch and in the other duties of dogs? Or do we entrust to the males the entire and exclusive care of the flocks, while we leave the females at home, under the idea that the bearing and suckling their puppies is labour enough for them?''The Republic'' states that women in Plato's ideal state should work alongside men, receive equal education, and share equally in all aspects of the state. The sole exception involved women working in capacities which required less physical strength. In the first century CE, the Roman Stoic philosopher

Gaius Musonius Rufus

Gaius Musonius Rufus (; grc-gre, Μουσώνιος Ῥοῦφος) was a Roman Stoic philosopher of the 1st century AD. He taught philosophy in Rome during the reign of Nero and so was sent into exile in 65 AD, returning to Rome only under Ga ...

entitled one of his 21 Discourses "That Women Too Should Study Philosophy", in which he argues for equal education of women in philosophy: "If you ask me what doctrine produces such an education, I shall reply that as without philosophy no man would be properly educated, so no woman would be. Moreover, not men alone, but women too, have a natural inclination toward virtue and the capacity for acquiring it, and it is the nature of women no less than men to be pleased by good and just acts and to reject the opposite of these. If this is true, by what reasoning would it ever be appropriate for men to search out and consider how they may lead good lives, which is exactly the study of philosophy, but inappropriate for women?"

Islamic world

While in the pre-modern period there was no formal feminist movement in Islamic nations, there were a number of important figures who spoke for improving women's rights and autonomy. The medieval mystic and philosopherIbn Arabi

Ibn ʿArabī ( ar, ابن عربي, ; full name: , ; 1165–1240), nicknamed al-Qushayrī (, ) and Sulṭān al-ʿĀrifīn (, , ' Sultan of the Knowers'), was an Arab Andalusian Muslim scholar, mystic, poet, and philosopher, extremely influen ...

argued that while men were favored over women as prophets, women were just as capable of sainthood

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Catholic, Eastern Orth ...

as men.

In the 12th century, the Sunni scholar Ibn Asakir wrote that women could study and earn ''ijazah

An ''ijazah'' ( ar, الإِجازَة, "permission", "authorization", "license"; plural: ''ijazahs'' or ''ijazat'') is a license authorizing its holder to transmit a certain text or subject, which is issued by someone already possessing such au ...

s'' in order to transmit religious texts like the hadiths

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

. This was especially the case for learned and scholarly families, who wanted to ensure the highest possible education for both their sons and daughters. However, some men did not approve of this practice, such as Muhammad ibn al-Hajj (died 1336), who was appalled by women speaking in loud voices and exposing their '' 'awra'' in the presence of men while listening to the recitation of books.

In the 12th century, the Islamic philosopher

Islamic philosophy is philosophy that emerges from the Islamic tradition. Two terms traditionally used in the Islamic world are sometimes translated as philosophy—falsafa (literally: "philosophy"), which refers to philosophy as well as logic ...

and ''qadi

A qāḍī ( ar, قاضي, Qāḍī; otherwise transliterated as qazi, cadi, kadi, or kazi) is the magistrate or judge of a ''sharīʿa'' court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and minor ...

'' (judge) Ibn Rushd

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology ...

, commenting on Plato's views in ''The Republic'' on equality between the sexes, concluded that while men were stronger, it was still possible for women to perform the same duties as men. In ''Bidayat al-mujtahid'' (The Distinguished Jurist's Primer) he added that such duties could include participation in warfare and expressed discontent with the fact that women in his society were typically limited to being mothers and wives. Several women are said to have taken part in battles or helped in them during the Muslim conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He estab ...

and fitnas, including Nusaybah bint Ka'ab

Nusaybah bint Ka'ab ( ar, نسيبة بنت كعب; also ''ʾUmm ʿAmmarah'', ''Umm Umara'', ''Umm marah''Ghadanfar, Mahmood Ahmad. "Great Women of Islam", Riyadh. 2001.pp. 207-215), was one of the early women to convert to Islam. She was one of t ...

and Aisha

Aisha ( ar, , translit=ʿĀʾisha bint Abī Bakr; , also , ; ) was Muhammad's third and youngest wife. In Islamic writings, her name is thus often prefixed by the title "Mother of the Believers" ( ar, links=no, , ʾumm al- muʾminīn), referr ...

.

Christian Medieval Europe

Here the dominant view was that women were intellectually and morally weaker than men, having been tainted by the original sin of Eve as described in biblical tradition. This was used to justify many limits placed on women, such as not being allowed to own property, or being obliged to obey fathers or husbands at all times. This view and curbs derived from it were disputed even in medieval times. Medieval protofeminists recognized as important to the development of feminism includeMarie de France

Marie de France (fl. 1160 to 1215) was a poet, possibly born in what is now France, who lived in England during the late 12th century. She lived and wrote at an unknown court, but she and her work were almost certainly known at the royal court o ...

, Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor ( – 1 April 1204; french: Aliénor d'Aquitaine, ) was Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of King Henry II, and Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right from ...

, Bettisia Gozzadini

Bettisia Gozzadini (1209 – 2 November 1261) was a jurist who lectured at the University of Bologna from about 1239. She is thought to be the first woman to have taught at a university.

Life

Gozzadini was born in the commune of Bologna, in ...

, Nicola de la Haye

Nicola de la Haie (born c. 1150; d. 1230), of Swaton in Lincolnshire, (also written de la Haye) was an England, English landowner and administrator who inherited from her father not only lands in both England and Normandy but also the post of her ...

, Christine de Pizan

Christine de Pizan or Pisan (), born Cristina da Pizzano (September 1364 – c. 1430), was an Italian poet and court writer for King Charles VI of France and several French dukes.

Christine de Pizan served as a court writer in medieval Franc ...

, Jadwiga of Poland

Jadwiga (; 1373 or 137417 July 1399), also known as Hedwig ( hu, Hedvig), was the first woman to be crowned as monarch of the Kingdom of Poland. She reigned from 16 October 1384 until her death. She was the youngest daughter of Louis the Great ...

, Laura Cereta

Laura Cereta (September 1469 – 1499), was one of the most notable humanist and feminist writers of fifteenth-century Italy. Cereta was the first to put women’s issues and her friendships with women front and center in her work. Cereta wrote i ...

, and La Malinche

Marina or Malintzin ( 1500 – 1529), more popularly known as La Malinche , a Nahua woman from the Mexican Gulf Coast, became known for contributing to the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire (1519–1521), by acting as an interpreter, ad ...

.

Women in the Peasants' Revolt

The EnglishPeasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, also named Wat Tyler's Rebellion or the Great Rising, was a major uprising across large parts of England in 1381. The revolt had various causes, including the socio-economic and political tensions generated by the Blac ...

of 1381 was a rebellion against serfdom, in which many women played prominent roles. On 14 June 1381, the Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. T ...

and Archbishop of Canterbury, Simon of Sudbury, was dragged from the Tower of London and beheaded. Leading the group was Johanna Ferrour, who ordered this in response to Sudbury's harsh poll taxes. She also ordered the beheading of the Lord High Treasurer, Sir Robert Hales

Sir Robert Hales ( – 14 June 1381) was Grand Prior of the Knights Hospitaller of England, Lord High Treasurer, and Admiral of the West. He was killed in the Peasants' Revolt.

Career

In 1372 Robert Hales became the Lord/Grand Prior of t ...

for his role in them. In addition to leading these rebels, Ferrour burned down the Savoy Palace

The Savoy Palace, considered the grandest nobleman's townhouse of medieval London, was the residence of prince John of Gaunt until it was destroyed during rioting in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. The palace was on the site of an estate given ...

and stole a duke's chest of gold. The Chief Justice John Cavendish was beheaded by Katherine Gamen, another female leader.

An Associate Professor of English at Bates College, Sylvia Federico, argues that women often had the strongest desire to participate in revolts, this one in particular. They did all that men did: they were just as violent in rebelling against the government, if not more so. Ferrour was not the only female leader of the revolt; others were involved — one woman indicted for encouraging an attack on a prison at Maidstone in Kent, another responsible for robbing a multitude of mansions, which left servants too scared to return afterwards. Although there were not many female leaders in the Peasants' Revolt, there were surprising numbers in the crowd, for instance, 70 in Suffolk. The women involved had valid reasons for desiring to be so and on occasions taking a leading role. The poll tax of 1380 was tougher on married women, so it is unsurprising that some women were as violent as men in their involvement. Their acts of violence signified mounting hatred for the government.

Hrotsvitha

Hrotsvitha

Hrotsvitha (c. 935–973) was a secular canoness who wrote drama and Christian poetry under the Ottonian dynasty. She was born in Bad Gandersheim to Saxon nobles and entered Gandersheim Abbey as a canoness. She is considered the first female wri ...

, a German secular canoness, was born about 935 and died about 973. Her work is still seen as important, as she was the first female writer from the German lands, the first female historian, and apparently the first person since antiquity to write dramas in the Latin West.

Since her rediscovery in the 1600s by Conrad Celtis, Hrotsvitha has become a source of particular interest and study for feminists, who have begun to place her work in a feminist context, some arguing that while Hrotsvitha was not a feminist, that she is important to the history of feminism.

European Renaissance

Restrictions on women

At the beginning of the renaissance, women's sole role and social value was held to be reproduction.

This gender role defined a woman's main identity and purpose in life.

At the beginning of the renaissance, women's sole role and social value was held to be reproduction.

This gender role defined a woman's main identity and purpose in life. Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

, a well-known exemplar of the love of wisdom to Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

humanists, said that he tolerated his first wife Xanthippe

Xanthippe (; , , ; 5th–4th century BCE) was an ancient Athenian, the wife of Socrates and mother of their three sons: Lamprocles, Sophroniscus, and Menexenus. She was likely much younger than Socrates, perhaps by as much as 40 years.

Name ...

because she bore him sons, in the same way as one tolerated the noise of geese because they produce eggs and chicks. This analogy perpetuated the claim that a woman's sole role was reproduction.

Marriage in the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

defined a woman: she was whom she married. Till marriage she remained her father's property. Each had few rights beyond privileges granted by a husband or father. She was expected to be chaste, obedient, pleasant, gentle, submissive, and unless sweet-spoken, silent. In William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's 1593 play ''The Taming of the Shrew

''The Taming of the Shrew'' is a comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1590 and 1592. The play begins with a framing device, often referred to as the induction, in which a mischievous nobleman tricks a drunken ...

'', Katherina is seen as unmarriageable for her headstrong, outspoken nature, unlike her mild sister Bianca. She is seen as a wayward shrew who needs taming into submission. Once tamed, she readily goes when Petruchio summons her, almost like a dog. Her submission is applauded; she is accepted as a proper woman, now "conformable to other household Kates."

Unsurprisingly, therefore, most women were barely educated. In a letter to Lady Baptista Maletesta of Montefeltro in 1424, the humanist Leonardo Bruni

Leonardo Bruni (or Leonardo Aretino; c. 1370 – March 9, 1444) was an Italian humanist, historian and statesman, often recognized as the most important humanist historian of the early Renaissance. He has been called the first modern historian. ...

wrote, "While you live in these times when learning has so far decayed that it is regarded as positively miraculous to meet a learned man, let alone a woman." eonardo Bruni, "Study of Literature to Lady Baptista Maletesta of Montefeltro," 1494./ref> Bruni himself thought women had no need of education because they were not engaged in social forums for which such discourse was needed. In the same letter he wrote,For why should the subtleties of... a thousand... rhetorical conundra consume the powers of a woman, who never sees the forum? The contests of the forum, like those of warfare and battle, are the sphere of men. Hers is not the task of learning to speak for and against witnesses, for and against torture, for and against reputation.... She will, in a word, leave the rough-and-tumble of the forum entirely to men."

"Witch literature"

Starting with theMalleus Maleficarum

The ''Malleus Maleficarum'', usually translated as the ''Hammer of Witches'', is the best known treatise on witchcraft. It was written by the German Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer (under his Latinized name ''Henricus Institor'') and firs ...

, Renaissance Europe saw the publication of numerous treatises on witches: their essence, their features, and ways to spot, prosecute and punish them. This helped to reinforce and perpetuate the view of women as morally corrupt sinners, and to retain the restrictions placed on them.

Advocating women's learning

Yet not all agreed with this negative view of women and the restrictions on them.Simone de Beauvoir

Simone Lucie Ernestine Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir (, ; ; 9 January 1908 – 14 April 1986) was a French existentialist philosopher, writer, social theorist, and feminist activist. Though she did not consider herself a philosopher, and even ...

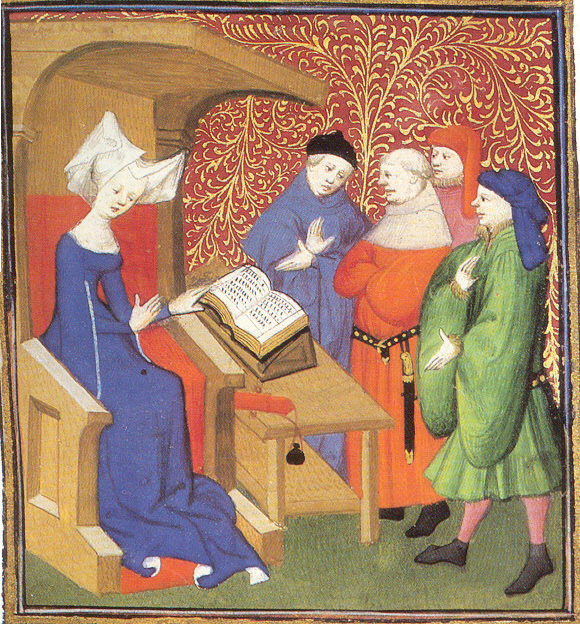

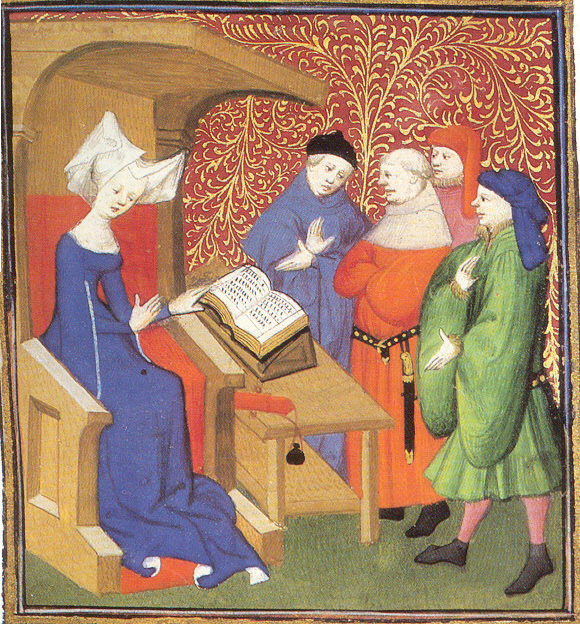

states, "The first time we see a woman take up her pen in defense of her sex" was when Christine de Pizan

Christine de Pizan or Pisan (), born Cristina da Pizzano (September 1364 – c. 1430), was an Italian poet and court writer for King Charles VI of France and several French dukes.

Christine de Pizan served as a court writer in medieval Franc ...

wrote ''Épître au Dieu d'Amour'' (Epistle to the God of Love) and ''The Book of the City of Ladies

''The Book of the City of Ladies'' or ''Le Livre de la Cité des Dames'' (finished by 1405), is perhaps Christine de Pizan's most famous literary work, and it is her second work of lengthy prose. Pizan uses the vernacular French language to compo ...

'', at the turn of the 15th century. An early male advocate of women's superiority was Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (; ; 14 September 1486 – 18 February 1535) was a German polymath, physician, legal scholar, soldier, theologian, and occult writer. Agrippa's ''Three Books of Occult Philosophy'' published in 1533 drew ...

in ''The Superior Excellence of Women Over Men''.

Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon (also spelt as Katherine, ; 16 December 1485 – 7 January 1536) was Queen of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII from their marriage on 11 June 1509 until their annulment on 23 May 1533. She was previously ...

, the first official female ambassador in European history, commissioned a book by Juan Luis Vives

Juan Luis Vives March ( la, Joannes Lodovicus Vives, lit=Juan Luis Vives; ca, Joan Lluís Vives i March; nl, Jan Ludovicus Vives; 6 March 6 May 1540) was a Spanish ( Valencian) scholar and Renaissance humanist w ...

arguing that women had a right to education, and encouraged and popularized education for women in England in her time as Henry VIII's wife.

Vives and fellow Renaissance humanist

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, at first Italian Renaissance, in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term ''humanist'' ( it, umanista ...

Agricola

Agricola, the Latin word for farmer, may also refer to:

People Cognomen or given name

:''In chronological order''

* Gnaeus Julius Agricola (40–93), Roman governor of Britannia (AD 77–85)

* Sextus Calpurnius Agricola, Roman governor of the mid ...

argued that aristocratic women at least required education. Roger Ascham

Roger Ascham (; c. 151530 December 1568)"Ascham, Roger" in '' The New Encyclopædia Britannica''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th edn., 1992, Vol. 1, p. 617. was an English scholar and didactic writer, famous for his prose style, ...

educated Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

, who read Latin and Greek and wrote occasional poems

Occasional poetry is poetry composed for a particular occasion. In the history of literature, it is often studied in connection with orality, performance, and patronage.

Term

As a term of literary criticism, "occasional poetry" describes the wor ...

such as '' On Monsieur's Departure'' that are still anthologized. She was seen as having talent without a woman's weakness, industry with a man's perseverance, and the body of a weak and feeble woman, but the heart and stomach of a king. The only way she could be seen as a good ruler was through manly qualities. Being a powerful and successful woman in the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

, like Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

, meant in some ways being male – a perception that limited women's potential as women.

Aristocratic women had greater chances of receiving an education, but it was not impossible for lower-class women to become literate. A woman named Margherita, living during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

, learned to read and write at the age of about 30, so there would be no mediator for the letters exchanged between her and her husband. Although Margherita defied gender role

A gender role, also known as a sex role, is a social role encompassing a range of behaviors and attitudes that are generally considered acceptable, appropriate, or desirable for a person based on that person's sex. Gender roles are usually cen ...

s, she became literate not to become a more enlightened person, but to be a better wife by gaining the ability to communicate with her husband directly.

Learned women in Early Modern Europe

Women who received an education often reached high standards of learning and wrote in defence of women and their rights. An example is the 16th-century Venetian authorModesta di Pozzo di Forzi

Moderata Fonte, directly translates to Modest Well is a pseudonym of Modesta di Pozzo di Forzi (or Zorzi), also known as Modesto Pozzo (or Modesta, feminization of Modesto), (1555–1592) was a Venetian writer and poet. Besides the posthumously ...

. The painter Sofonisba Anguissola

Sofonisba Anguissola ( – 16 November 1625), also known as Sophonisba Angussola or Sophonisba Anguisciola, was an Italian Renaissance painter born in Cremona to a relatively poor noble family. She received a well-rounded education that i ...

(c. 1532–1625) was born into an enlightened family in Cremona

Cremona (, also ; ; lmo, label= Cremunés, Cremùna; egl, Carmona) is a city and ''comune'' in northern Italy, situated in Lombardy, on the left bank of the Po river in the middle of the ''Pianura Padana'' (Po Valley). It is the capital of the ...

. She and her sisters were educated to male standards, and four out of five became professional painters. Sofonisba was the most successful of all, crowning her career as court painter to the Spanish king Philip II.

The famous Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

salons that held intelligent debate and lectures were not welcoming to women. This exclusion from public forums led to problems for educated women. Despite these constraints, many women were capable voices of new ideas. Isotta Nogarola

Isotta Nogarola (1418–1466) was an Italian writer and intellectual who is said to be the first major female humanist and one of the most important humanists of the Italian Renaissance. She inspired generations of artists and writers, among them ...

fought to belie such literary misogyny through defenses of women in biographical work and the exoneration of Eve. She made a space for women's voice in this time period, being regarded as a female intellectual. Similarly, Laura Cereta

Laura Cereta (September 1469 – 1499), was one of the most notable humanist and feminist writers of fifteenth-century Italy. Cereta was the first to put women’s issues and her friendships with women front and center in her work. Cereta wrote i ...

re-imagined the role of women in society and argued that education is a right for all humans and going so far as to say that women were at fault for not seizing their educational rights. Cassandra Fedele was the first to join a humanist gentleman's club, declaring that womanhood was a point of pride and equality of the sexes was essential. Other women including Margaret Roper

Margaret Roper (1505–1544) was an English writer and translator. Roper, the eldest daughter of Sir Thomas More, is considered to have been one of the most learned women in sixteenth-century England. She is celebrated for her filial piety and sc ...

, Mary Basset and the Cooke sisters gained recognition as scholars by making important translating contributions. Moderata Fonte

Moderata Fonte, directly translates to Modest Well is a pseudonym of Modesta di Pozzo di Forzi (or Zorzi), also known as Modesto Pozzo (or Modesta, feminization of Modesto), (1555–1592) was a Venetian writer and poet. Besides the posthumously ...

and Lucrezia Marinella were among some of the first women to adopt male rhetoric styles to rectify the inferior social context for women. Men at the time also recognised that certain women intellectuals had possibilities, and began writing their biographies, as Jacopo Filippo Tomasini did. The modern scholar Diana Robin outlined the history of intellectual women as a long and noble lineage.

The Reformation

TheReformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and i ...

was a milestone in the development of women's rights and education. As Protestantism

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

rested on believers' direct interaction with God, the ability to read the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts o ...

and prayer books suddenly became necessary to all, including women and girls. Protestant communities started to set up schools where ordinary boys and girls were taught basic literacy.

Protestants no longer saw women as weak and evil sinners, but as worthy companions of men needing education to become capable wives.

Spanish colonial America

India Juliana

India Juliana

Juliana (), better known as the India Juliana ( Spanish for "Indian Juliana" or "Juliana the Indian"), is the Christian name of a Guaraní woman who lived in the newly founded Asunción, in early-colonial Paraguay, known for killing a Spanish ...

, was the Christian name

A Christian name, sometimes referred to as a baptismal name, is a religious personal name given on the occasion of a Christian baptism, though now most often assigned by parents at birth. In English-speaking cultures, a person's Christian nam ...

of a Guaraní woman who lived in the newly-founded Asunción

Asunción (, , , Guarani: Paraguay) is the capital and the largest city of Paraguay.

The city stands on the eastern bank of the Paraguay River, almost at the confluence of this river with the Pilcomayo River. The Paraguay River and the Bay o ...

, in early-colonial Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to th ...

, known for killing a Spanish colonist between 1538 and 1542. She was one of the many indigenous women who were handed over to the Spanish colonists

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance ethnic group native to Spain. Within Spain, there are a number of national and regional ethnic identities that reflect the country's complex history, including a number of different languages, both i ...

and forced to move to their settlements to serve them and bear children. Juliana poisoned her Spaniard master and boasted of her actions to her peers, ending up executed as a warning to other indigenous women not to do the same.

Today, the India Juliana is regarded as an early feminist and a symbol of women's liberation, and her figure is of special interest for Paraguayan women

A woman is an adult female human. Prior to adulthood, a female human is referred to as a girl (a female child or adolescent). The plural ''women'' is sometimes used in certain phrases such as "women's rights" to denote female humans regardl ...

and feminist historians

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male poi ...

. The figure of the India Juliana has been reclaimed as a foremother by Paraguayan academics and activists as part of a process of "recovery of feminist and women's genealogies" in South America, intended to move away from the Eurocentric

Eurocentrism (also Eurocentricity or Western-centrism)

is a worldview that is centered on Western civilization or a biased view that favors it over non-Western civilizations. The exact scope of Eurocentrism varies from the entire Western wo ...

vision. The same has happened in Ecuador with Dolores Cacuango and Tránsito Amaguaña; in the central Andes

The Andes, Andes Mountains or Andean Mountains (; ) are the longest continental mountain range in the world, forming a continuous highland along the western edge of South America. The range is long, wide (widest between 18°S – 20°S ...

region with Bartolina Sisa and Micaela Bastidas; and in Argentina with María Remedios del Valle and Juana Azurduy

Juana Azurduy de Padilla (July 12, 1780 – May 25, 1862) was a guerrilla military leader from Chuquisaca, Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata (now Sucre, Bolivia).Pallis, Michael “Slaves of Slaves: The Challenge of Latin American Women” (Lon ...

. According to the researcher Silvia Tieffemberg, her revenge "crossed ethnic and gender barriers simultaneously." Several feminist groups, schools, libraries and centers for the promotion of women in Paraguay are named after her, and she is "carried as a banner" in the annual demonstrations of International Women's Day

International Women's Day (IWD) is a global holiday list of minor secular observances#March, celebrated annually on March 8 as a focal point in the women's rights, women's rights movement, bringing attention to issues such as gender equality, ...

and the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women

The United Nations General Assembly has designated November 25 as the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women ( Resolution 54/134). The premise of the day is to raise awareness around the world that women are subjected to ...

.

Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz

Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz was a nun in colonial

Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz was a nun in colonial New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

in the 17th century. She was an illegitimate Criolla, born to an absent Spanish father and a Criolla mother. Not only was she highly intelligent, but also self-educated, having studied in her wealthy grandfather's library. Sor Juana as a woman was barred from entering formal education. She pleaded with her mother to let her masculinize her appearance and attend university under a male guise. After the Vicereine Leonor Carreto took Sor Juana under her wing, the Viceroy, the Marquis de Mancera, provided Sor Juana with the chance to prove her intelligence. She exceeded all expectations, and legitimized by the vice-regal court, established a reputation for herself as an intellectual.

For reasons still debated, Sor Juana became a nun. While in the convent, she became a controversial figure, advocating recognition of women theologians, criticizing the patriarchal and colonial structures of the Church, and publishing her own writing, in which she set herself as an authority. Sor Juana also advocated for universal education and language rights. Not only did she contribute to the historic discourse of the Querelle des Femmes, but she has also been recognized as a protofeminist, religious feminist, and ecofeminist, and is connected with lesbian feminism

Lesbian feminism is a cultural movement and critical perspective that encourages women to focus their efforts, attentions, relationships, and activities towards their fellow women rather than men, and often advocates lesbianism as the log ...

.

17th century

Nonconformism, protectorate and restoration

Marie de Gournay (1565–1645) edited the third edition of Michel de Montaigne's ''Essays

An essay is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a letter, a paper, an article, a pamphlet, and a short story. Essays have been sub-classified as forma ...

'' after his death. She also wrote two feminist essays: ''The Equality of Men and Women'' (1622) and ''The Ladies' Grievance'' (1626). In 1673, François Poullain de la Barre

François Poullain de la Barre (; July 1647 – 4 May 1723) was an author, Catholic priest, and a Cartesian philosopher.

Life

François Poullain de la Barre was born on July 1647 in Paris, France, to a family with judicial nobility. He added "de ...

wrote ''De l'Ėgalité des deux sexes'' (On the equality of the two sexes).

The 17th century saw many new nonconformist sects such as the Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

give women greater freedom of expression. Noted feminist writers included Rachel Speght, Katherine Evans, Sarah Chevers, Margaret Fell

Margaret Fell orMargaret Fox ( Askew, formerly Fell; 1614 – 23 April 1702) was a founder of the Religious Society of Friends. Known popularly as the "mother of Quakerism," she is considered one of the Valiant Sixty early Quaker preachers and m ...

(a founding Quaker), Mary Forster and Sarah Blackborow

Sarah Blackborow (fl. 1650s – 1660s) was the English author of religious tracts, which strongly influenced Quaker thinking on social problems and the theological position of women. She was one of several prominent female activists in the early ...

. This gave prominence to some female ministers and writers such as Mary Mollineux and Barbara Blaugdone in Quakerism's early decades.

In general, though, women who preached or expressed opinions on religion were in danger of being suspected of lunacy or witchcraft, and many, like Anne Askew

Anne Askew (sometimes spelled Ayscough or Ascue) married name Anne Kyme, (152116 July 1546) was an English writer, poet, and Anabaptist preacher who was condemned as a heretic during the reign of Henry VIII of England. She and Margaret Cheyne a ...

, who was burned at the stake for heresy,Lerner, Gerda. "Religion and the creation of feminist consciousness". Harvard Divinity Bulletin November 2002died "for their implicit or explicit challenge to the patriarchal order".

In France and England, feminist ideas were attributes of

In France and England, feminist ideas were attributes of heterodoxy

In religion, heterodoxy (from Ancient Greek: , "other, another, different" + , "popular belief") means "any opinions or doctrines at variance with an official or orthodox position". Under this definition, heterodoxy is similar to unorthodoxy, w ...

, such as the Waldensians

The Waldensians (also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi or Vaudois) are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation.

Originally known as the "Poor Men of Lyon" in ...

and Catharists, rather than orthodoxy. Religious egalitarianism, such as that embraced by the Levellers

The Levellers were a political movement active during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms who were committed to popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law and religious tolerance. The hallmark of Leveller thought was its populi ...

, carried over into gender equality and so had political implications. Leveller women mounted demonstrations and petitions for equal rights, although dismissed by the authorities of the day.

The 17th century also saw more women writers emerging, such as Anne Bradstreet

Anne Bradstreet (née Dudley; March 8, 1612 – September 16, 1672) was the most prominent of early English poets of North America and first writer in England's North American colonies to be published. She is the first Puritan figure in ...

, Bathsua Makin

Bathsua Reginald Makin (; 1600 – c. 1675) was a teacher who contributed to the emerging criticism of woman's position in the domestic and public spheres in 17th-century England. Herself a highly educated woman, Makin was referred to as Englan ...

, Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, Lady Mary Wroth, the anonymous Eugenia

''Eugenia'' is a genus of flowering plants in the myrtle family Myrtaceae. It has a worldwide, although highly uneven, distribution in tropical and subtropical regions. The bulk of the approximately 1,100 species occur in the New World tropics, ...

, Mary Chudleigh

Mary, Lady Chudleigh (; August 1656–1710) was an English poet who belonged to an intellectual circle that included Mary Astell, Elizabeth Thomas, Judith Drake, Elizabeth Elstob, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, and John Norris. In her later ...

, and Mary Astell

Mary Astell (12 November 1666 – 11 May 1731) was an English protofeminist writer, philosopher, and rhetorician. Her advocacy of equal educational opportunities for women has earned her the title "the first English feminist."Batchelor, Jennie, ...

, who depicted women's changing roles and pleaded for their education. However, they encountered hostility, as shown by the experiences of Cavendish and of Wroth, whose work was unpublished until the 20th century.

Seventeenth-century France saw the rise of salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon ...

s – cultural gathering places of the upper-class intelligentsia – which were run by women and in which they took part as artists. But while women gained salon membership, they stayed in the background, writing "but not for ublication. Despite their limited role in the salons, Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revol ...

saw them as a "threat to the 'natural' dominance of men".

Mary Astell is often described as the first feminist writer, although this ignores the intellectual debt she owed to Anna Maria van Schurman

Anna Maria van Schurman (November 5, 1607 – May 4, 1678) was a Dutch painter, engraver, poet, and scholar, who is best known for her exceptional learning and her defence of female education. She was a highly educated woman, who excelled i ...

, Bathsua Makin

Bathsua Reginald Makin (; 1600 – c. 1675) was a teacher who contributed to the emerging criticism of woman's position in the domestic and public spheres in 17th-century England. Herself a highly educated woman, Makin was referred to as Englan ...

and others who preceded her. She was certainly among the earliest feminist writers in English, whose analyses remain relevant today, and who moved beyond earlier writers by instituting educational institutions for women.Joan Kinnaird, "Mary Astell: Inspired by ideas" in D. Spender, ed., ''Feminist Theories'', p. 29. Astell and Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn (; bapt. 14 December 1640 – 16 April 1689) was an English playwright, poet, prose writer and translator from the Restoration era. As one of the first English women to earn her living by her writing, she broke cultural barrie ...

together laid the groundwork for feminist theory in the 17th century. No woman would speak out as strongly again for another century. In historical accounts, Astell is often overshadowed by her younger and more colourful friend and correspondent Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (née Pierrepont; 15 May 168921 August 1762) was an English aristocrat, writer, and poet. Born in 1689, Lady Mary spent her early life in England. In 1712, Lady Mary married Edward Wortley Montagu, who later served ...

.

Relaxation of social values and secularization in the English Restoration

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland took place in 1660 when King Charles II returned from exile in continental Europe. The preceding period of the Protectorate and the civil wars came to ...

provided new chances for women in the arts, which they used to advance their cause. Yet female playwrights encountered similar hostility, including Catherine Trotter Cockburn, Mary Manley and Mary Pix. The most influential of allWalters, Margaret. ''Feminism: A Very Short Introduction''. Oxford University, 2005 (). was Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn (; bapt. 14 December 1640 – 16 April 1689) was an English playwright, poet, prose writer and translator from the Restoration era. As one of the first English women to earn her living by her writing, she broke cultural barrie ...

, one of the first English women to earn her living as a writer, who was influential as a novelist, playwright and political propagandist.Janet Todd, p. 2. Although successful in her lifetime, Behn was often vilified as "unwomanly" by 18th-century writers like Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding (22 April 1707 – 8 October 1754) was an English novelist, irony writer, and dramatist known for earthy humour and satire. His comic novel ''Tom Jones'' is still widely appreciated. He and Samuel Richardson are seen as founders ...

and Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson (baptised 19 August 1689 – 4 July 1761) was an English writer and printer known for three epistolary novels: '' Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' (1740), '' Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady'' (1748) and ''The History ...

. Likewise, the 19th-century critic Julia Kavanagh said that "instead of raising man to woman's moral standards ehnsank to the level of man's courseness." Not until the 20th century would Behn gain a wider readership and critical acceptance. Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer, considered one of the most important modernist 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

Woolf was born ...

praised her: "All women together ought to let flowers fall upon the grave of Aphra Behn... for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds."

Major feminist writers in continental Europe included Marguerite de Navarre

Marguerite de Navarre (french: Marguerite d'Angoulême, ''Marguerite d'Alençon''; 11 April 149221 December 1549), also known as Marguerite of Angoulême and Margaret of Navarre, was a princess of France, Duchess of Alençon and Berry, and Quee ...

, Marie de Gournay and Anna Maria van Schurman

Anna Maria van Schurman (November 5, 1607 – May 4, 1678) was a Dutch painter, engraver, poet, and scholar, who is best known for her exceptional learning and her defence of female education. She was a highly educated woman, who excelled i ...

, who attacked misogyny and promoted women's education. In Switzerland, the first printed publication by a woman appeared in 1694: in ''Glaubens-Rechenschafft'', Hortensia von Moos argued against the idea that women should stay silent. The previous year saw publication of an anonymous tract, ''Rose der Freyheit'' (Rose of Freedom), whose author denounced male dominance and abuse of women.

In the New World, the Mexican nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 599. The term is ...

, Juana Ines de la Cruz

Juana is a Spanish language, Spanish female first name. It is the feminine form of Juan (English John (given name), John), and thus corresponds to the English names Jane (given name), Jane, Janet (given name), Janet, Jean (female given name), Je ...

(1651–1695), advanced the education of women in her essay "Reply to Sor Philotea". By the end of the 17th century women's voices were becoming increasingly heard at least by educated women. Literature in the last decades of the century was sometimes referred to as the "Battle of the Sexes", and was often surprisingly polemic, such as Hannah Woolley's ''The Gentlewoman's Companion''.Hannah Woolley, ''The Gentlewoman's Companion'', London, 1675. However, women received mixed messages, for there was also a strident backlash and even self-deprecation by some women writers in response. They were also subjected to conflicting social pressures: fewer opportunities for work outside the home, and education that sometimes reinforced the social order as much as inspired independent thinking.

See also

*History of feminism

The history of feminism comprises the narratives (chronological or thematic) of the movements and ideologies which have aimed at equal rights for women. While feminists around the world have differed in causes, goals, and intentions depending ...

References

{{reflist, 30em Feminism and history Feminism and the arts Protofeminism