Proteinsynthesis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Protein biosynthesis (or protein synthesis) is a core biological process, occurring inside

Protein biosynthesis (or protein synthesis) is a core biological process, occurring inside

The enzyme

The enzyme

Once transcription is complete, the pre-mRNA molecule undergoes

Once transcription is complete, the pre-mRNA molecule undergoes

During translation, ribosomes synthesize polypeptide chains from mRNA template molecules. In eukaryotes, translation occurs in the cytoplasm of the cell, where the ribosomes are located either free floating or attached to the

During translation, ribosomes synthesize polypeptide chains from mRNA template molecules. In eukaryotes, translation occurs in the cytoplasm of the cell, where the ribosomes are located either free floating or attached to the

Once synthesis of the polypeptide chain is complete, the polypeptide chain folds to adopt a specific structure which enables the protein to carry out its functions. The basic form of

Once synthesis of the polypeptide chain is complete, the polypeptide chain folds to adopt a specific structure which enables the protein to carry out its functions. The basic form of

Cleavage of proteins is an irreversible post-translational modification carried out by enzymes known as

Cleavage of proteins is an irreversible post-translational modification carried out by enzymes known as

Following translation, small chemical groups can be added onto amino acids within the mature protein structure. Examples of processes which add chemical groups to the target protein include methylation,

Following translation, small chemical groups can be added onto amino acids within the mature protein structure. Examples of processes which add chemical groups to the target protein include methylation,

Post-translational modifications can incorporate more complex, large molecules into the folded protein structure. One common example of this is

Post-translational modifications can incorporate more complex, large molecules into the folded protein structure. One common example of this is

Many proteins produced within the cell are secreted outside the cell to function as

Many proteins produced within the cell are secreted outside the cell to function as

Sickle cell disease is a group of diseases caused by a mutation in a subunit of hemoglobin, a protein found in red blood cells responsible for transporting oxygen. The most dangerous of the sickle cell diseases is known as sickle cell anemia. Sickle cell anemia is the most common homozygous recessive single gene disorder, meaning the affected individual must carry a mutation in both copies of the affected gene (one inherited from each parent) to experience the disease. Hemoglobin has a complex quaternary structure and is composed of four polypeptide subunits - two A subunits and two B subunits. Patients with sickle cell anemia have a missense or substitution mutation in the gene encoding the hemoglobin B subunit polypeptide chain. A missense mutation means the nucleotide mutation alters the overall codon triplet such that a different amino acid is paired with the new codon. In the case of sickle cell anemia, the most common missense mutation is a single nucleotide mutation from thymine to adenine in the hemoglobin B subunit gene. This changes codon 6 from encoding the amino acid glutamic acid to encoding valine.

This change in the primary structure of the hemoglobin B subunit polypeptide chain alters the functionality of the hemoglobin multi-subunit complex in low oxygen conditions. When red blood cells unload oxygen into the tissues of the body, the mutated haemoglobin protein starts to stick together to form a semi-solid structure within the red blood cell. This distorts the shape of the red blood cell, resulting in the characteristic "sickle" shape, and reduces cell flexibility. This rigid, distorted red blood cell can accumulate in blood vessels creating a blockage. The blockage prevents blood flow to tissues and can lead to tissue death which causes great pain to the individual.

Sickle cell disease is a group of diseases caused by a mutation in a subunit of hemoglobin, a protein found in red blood cells responsible for transporting oxygen. The most dangerous of the sickle cell diseases is known as sickle cell anemia. Sickle cell anemia is the most common homozygous recessive single gene disorder, meaning the affected individual must carry a mutation in both copies of the affected gene (one inherited from each parent) to experience the disease. Hemoglobin has a complex quaternary structure and is composed of four polypeptide subunits - two A subunits and two B subunits. Patients with sickle cell anemia have a missense or substitution mutation in the gene encoding the hemoglobin B subunit polypeptide chain. A missense mutation means the nucleotide mutation alters the overall codon triplet such that a different amino acid is paired with the new codon. In the case of sickle cell anemia, the most common missense mutation is a single nucleotide mutation from thymine to adenine in the hemoglobin B subunit gene. This changes codon 6 from encoding the amino acid glutamic acid to encoding valine.

This change in the primary structure of the hemoglobin B subunit polypeptide chain alters the functionality of the hemoglobin multi-subunit complex in low oxygen conditions. When red blood cells unload oxygen into the tissues of the body, the mutated haemoglobin protein starts to stick together to form a semi-solid structure within the red blood cell. This distorts the shape of the red blood cell, resulting in the characteristic "sickle" shape, and reduces cell flexibility. This rigid, distorted red blood cell can accumulate in blood vessels creating a blockage. The blockage prevents blood flow to tissues and can lead to tissue death which causes great pain to the individual.

Cancers form as a result of gene mutations as well as improper protein translation. In addition to cancer cells proliferating abnormally, they suppress the expression of anti-apoptotic or pro-apoptotic genes or proteins. Most cancer cells see a mutation in the signaling protein Ras, which functions as an on/off signal transductor in cells. In cancer cells, the RAS protein becomes persistently active, thus promoting the proliferation of the cell due to the absence of any regulation. Additionally, most cancer cells carry two mutant copies of the regulator gene p53, which acts as a gatekeeper for damaged genes and initiates apoptosis in malignant cells. In its absence, the cell cannot initiate apoptosis or signal for other cells to destroy it.

As the tumor cells proliferate, they either remain confined to one area and are called benign, or become malignant cells that migrate to other areas of the body. Oftentimes, these malignant cells secrete proteases that break apart the extracellular matrix of tissues. This then allows the cancer to enter its terminal stage called Metastasis, in which the cells enter the bloodstream or the lymphatic system to travel to a new part of the body.

Cancers form as a result of gene mutations as well as improper protein translation. In addition to cancer cells proliferating abnormally, they suppress the expression of anti-apoptotic or pro-apoptotic genes or proteins. Most cancer cells see a mutation in the signaling protein Ras, which functions as an on/off signal transductor in cells. In cancer cells, the RAS protein becomes persistently active, thus promoting the proliferation of the cell due to the absence of any regulation. Additionally, most cancer cells carry two mutant copies of the regulator gene p53, which acts as a gatekeeper for damaged genes and initiates apoptosis in malignant cells. In its absence, the cell cannot initiate apoptosis or signal for other cells to destroy it.

As the tumor cells proliferate, they either remain confined to one area and are called benign, or become malignant cells that migrate to other areas of the body. Oftentimes, these malignant cells secrete proteases that break apart the extracellular matrix of tissues. This then allows the cancer to enter its terminal stage called Metastasis, in which the cells enter the bloodstream or the lymphatic system to travel to a new part of the body.

A useful video visualising the process of converting DNA to protein via transcription and translation

Video visualising the process of protein folding from the non-functional primary structure to a mature, folded 3D protein structure with reference to the role of mutations and protein mis-folding in disease

A more advanced video detailing the different types of post-translational modifications and their chemical structures

{{Authority control Gene expression Proteins Biosynthesis Metabolism

Protein biosynthesis (or protein synthesis) is a core biological process, occurring inside

Protein biosynthesis (or protein synthesis) is a core biological process, occurring inside cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

, balancing the loss of cellular protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s (via degradation

Degradation may refer to:

Science

* Degradation (geology), lowering of a fluvial surface by erosion

* Degradation (telecommunications), of an electronic signal

* Biodegradation of organic substances by living organisms

* Environmental degradation ...

or export

An export in international trade is a good produced in one country that is sold into another country or a service provided in one country for a national or resident of another country. The seller of such goods or the service provider is an ...

) through the production of new proteins. Proteins perform a number of critical functions as enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s, structural proteins or hormone

A hormone (from the Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs by complex biological processes to regulate physiology and behavior. Hormones are required ...

s. Protein synthesis is a very similar process for both prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

s and eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s but there are some distinct differences.

Protein synthesis can be divided broadly into two phases - transcription

Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including:

Genetics

* Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ...

and translation

Translation is the communication of the Meaning (linguistic), meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The ...

. During transcription, a section of DNA encoding a protein, known as a gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

, is converted into a template molecule called messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the p ...

(mRNA). This conversion is carried out by enzymes, known as RNA polymerases

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that synthesizes RNA from a DNA template.

Using the enzyme helicase, RNAP locally opens the ...

, in the nucleus of the cell. In eukaryotes, this mRNA is initially produced in a premature form (pre-mRNA

A primary transcript is the single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA) product synthesized by transcription of DNA, and processed to yield various mature RNA products such as mRNAs, tRNAs, and rRNAs. The primary transcripts designated to be mRNAs a ...

) which undergoes post-transcriptional modification

Transcriptional modification or co-transcriptional modification is a set of biological processes common to most eukaryotic cells by which an RNA primary transcript is chemically altered following transcription from a gene to produce a mature, func ...

s to produce mature mRNA

Mature messenger RNA, often abbreviated as mature mRNA is a eukaryotic RNA transcript that has been spliced and processed and is ready for translation in the course of protein synthesis. Unlike the eukaryotic RNA immediately after transcription k ...

. The mature mRNA is exported from the cell nucleus via nuclear pore

A nuclear pore is a part of a large complex of proteins, known as a nuclear pore complex that spans the nuclear envelope, which is the double membrane surrounding the eukaryotic cell nucleus. There are approximately 1,000 nuclear pore complexes ...

s to the cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

of the cell for translation to occur. During translation, the mRNA is read by ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

s which use the nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules wi ...

sequence of the mRNA to determine the sequence of amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s. The ribosomes catalyze the formation of covalent

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms ...

peptide bond

In organic chemistry, a peptide bond is an amide type of covalent chemical bond linking two consecutive alpha-amino acids from C1 (carbon number one) of one alpha-amino acid and N2 (nitrogen number two) of another, along a peptide or protein cha ...

s between the encoded amino acids to form a polypeptide chain

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

A p ...

.

Following translation the polypeptide chain must fold to form a functional protein; for example, to function as an enzyme the polypeptide chain must fold correctly to produce a functional active site

In biology and biochemistry, the active site is the region of an enzyme where substrate molecules bind and undergo a chemical reaction. The active site consists of amino acid residues that form temporary bonds with the substrate (binding site) a ...

. In order to adopt a functional three-dimensional (3D) shape, the polypeptide chain must first form a series of smaller underlying structures called secondary structures

Secondary may refer to: Science and nature

* Secondary emission, of particles

** Secondary electrons, electrons generated as ionization products

* The secondary winding, or the electrical or electronic circuit connected to the secondary winding ...

. The polypeptide chain in these secondary structures then folds to produce the overall 3D tertiary structure

Protein tertiary structure is the three dimensional shape of a protein. The tertiary structure will have a single polypeptide chain "backbone" with one or more protein secondary structures, the protein domains. Amino acid side chains may int ...

. Once correctly folded, the protein can undergo further maturation through different post-translational modification

Post-translational modification (PTM) is the covalent and generally enzymatic modification of proteins following protein biosynthesis. This process occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and the golgi apparatus. Proteins are synthesized by ribosome ...

s. Post-translational modifications can alter the protein's ability to function, where it is located within the cell (e.g. cytoplasm or nucleus) and the protein's ability to interact with other proteins.

Protein biosynthesis has a key role in disease as changes and errors in this process, through underlying DNA mutations

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mitos ...

or protein misfolding, are often the underlying causes of a disease. DNA mutations change the subsequent mRNA sequence, which then alters the mRNA encoded amino acid sequence. Mutations can cause the polypeptide chain to be shorter by generating a stop sequence which causes early termination of translation. Alternatively, a mutation in the mRNA sequence changes the specific amino acid encoded at that position in the polypeptide chain. This amino acid change can impact the protein's ability to function or to fold correctly. Misfolded proteins are often implicated in disease as improperly folded proteins have a tendency to stick together to form dense protein clumps. These clumps are linked to a range of diseases, often neurological

Neurology (from el, νεῦρον (neûron), "string, nerve" and the suffix -logia, "study of") is the branch of medicine dealing with the diagnosis and treatment of all categories of conditions and disease involving the brain, the spinal ...

, including Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegeneration, neurodegenerative disease that usually starts slowly and progressively worsens. It is the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in short-term me ...

and Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a long-term degenerative disorder of the central nervous system that mainly affects the motor system. The symptoms usually emerge slowly, and as the disease worsens, non-motor symptoms becom ...

.

Transcription

Transcription occurs in the nucleus using DNA as a template to produce mRNA. In eukaryotes, this mRNA molecule is known as pre-mRNA as it undergoes post-transcriptional modifications in the nucleus to produce a mature mRNA molecule. However, in prokaryotes post-transcriptional modifications are not required so the mature mRNA molecule is immediately produced by transcription. Initially, an enzyme known as ahelicase

Helicases are a class of enzymes thought to be vital to all organisms. Their main function is to unpack an organism's genetic material. Helicases are motor proteins that move directionally along a nucleic acid phosphodiester backbone, separatin ...

acts on the molecule of DNA. DNA has an antiparallel, double helix structure composed of two, complementary polynucleotide

A polynucleotide molecule is a biopolymer composed of 13 or more nucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (D ...

strands, held together by hydrogen bond

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (or H-bond) is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bound to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a ...

s between the base pairs. The helicase disrupts the hydrogen bonds causing a region of DNA - corresponding to a gene - to unwind, separating the two DNA strands and exposing a series of bases. Despite DNA being a double stranded molecule, only one of the strands acts as a template for pre-mRNA synthesis - this strand is known as the template strand. The other DNA strand (which is complementary

A complement is something that completes something else.

Complement may refer specifically to:

The arts

* Complement (music), an interval that, when added to another, spans an octave

** Aggregate complementation, the separation of pitch-class ...

to the template strand) is known as the coding strand.

Both DNA and RNA have intrinsic directionality, meaning there are two distinct ends of the molecule. This property of directionality is due to the asymmetrical underlying nucleotide subunits, with a phosphate group on one side of the pentose sugar and a base on the other. The five carbons in the pentose sugar are numbered from 1' (where ' means prime) to 5'. Therefore, the phosphodiester bonds connecting the nucleotides are formed by joining the hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy ...

group on the 3' carbon of one nucleotide to the phosphate group on the 5' carbon of another nucleotide. Hence, the coding strand of DNA runs in a 5' to 3' direction and the complementary, template DNA strand runs in the opposite direction from 3' to 5'.

The enzyme

The enzyme RNA polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that synthesizes RNA from a DNA template.

Using the enzyme helicase, RNAP locally opens the ...

binds to the exposed template strand and reads from the gene in the 3' to 5' direction. Simultaneously, the RNA polymerase synthesizes a single strand of pre-mRNA in the 5'-to-3' direction by catalysing the formation of phosphodiester bonds

In chemistry, a phosphodiester bond occurs when exactly two of the hydroxyl groups () in phosphoric acid react with hydroxyl groups on other molecules to form two ester bonds. The "bond" involves this linkage . Discussion of phosphodiesters is d ...

between activated nucleotides (free in the nucleus) that are capable of complementary base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

ing with the template strand. Behind the moving RNA polymerase the two strands of DNA rejoin, so only 12 base pairs of DNA are exposed at one time. RNA polymerase builds the pre-mRNA molecule at a rate of 20 nucleotides per second enabling the production of thousands of pre-mRNA molecules from the same gene in an hour. Despite the fast rate of synthesis, the RNA polymerase enzyme contains its own proofreading mechanism. The proofreading mechanisms allows the RNA polymerase to remove incorrect nucleotides (which are not complementary to the template strand of DNA) from the growing pre-mRNA molecule through an excision reaction. When RNA polymerases reaches a specific DNA sequence which terminates transcription, RNA polymerase detaches and pre-mRNA synthesis is complete.

The pre-mRNA molecule synthesized is complementary to the template DNA strand and shares the same nucleotide sequence as the coding DNA strand. However, there is one crucial difference in the nucleotide composition of DNA and mRNA molecules. DNA is composed of the bases - guanine

Guanine () ( symbol G or Gua) is one of the four main nucleobases found in the nucleic acids DNA and RNA, the others being adenine, cytosine, and thymine (uracil in RNA). In DNA, guanine is paired with cytosine. The guanine nucleoside is called ...

, cytosine

Cytosine () ( symbol C or Cyt) is one of the four nucleobases found in DNA and RNA, along with adenine, guanine, and thymine (uracil in RNA). It is a pyrimidine derivative, with a heterocyclic aromatic ring and two substituents attached (an am ...

, adenine

Adenine () ( symbol A or Ade) is a nucleobase (a purine derivative). It is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The three others are guanine, cytosine and thymine. Its derivati ...

and thymine

Thymine () ( symbol T or Thy) is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The others are adenine, guanine, and cytosine. Thymine is also known as 5-methyluracil, a pyrimidine nu ...

(G, C, A and T) - RNA is also composed of four bases - guanine, cytosine, adenine and uracil

Uracil () (symbol U or Ura) is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid RNA. The others are adenine (A), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). In RNA, uracil binds to adenine via two hydrogen bonds. In DNA, the uracil nucleobase is replaced by ...

. In RNA molecules, the DNA base thymine is replaced by uracil which is able to base pair with adenine. Therefore, in the pre-mRNA molecule, all complementary bases which would be thymine in the coding DNA strand are replaced by uracil.

Post-transcriptional modifications

Once transcription is complete, the pre-mRNA molecule undergoes

Once transcription is complete, the pre-mRNA molecule undergoes post-transcriptional modification

Transcriptional modification or co-transcriptional modification is a set of biological processes common to most eukaryotic cells by which an RNA primary transcript is chemically altered following transcription from a gene to produce a mature, func ...

s to produce a mature mRNA molecule.

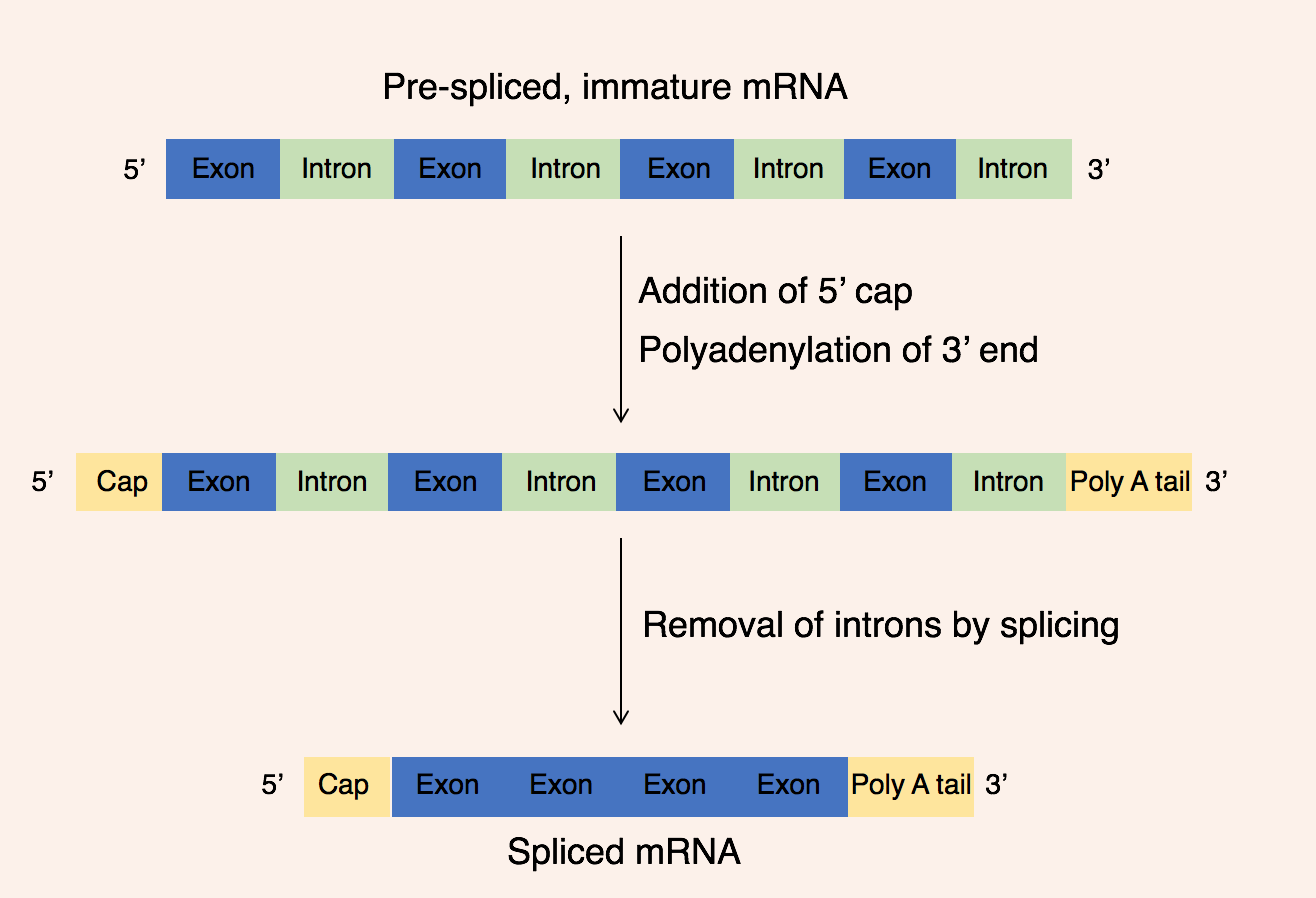

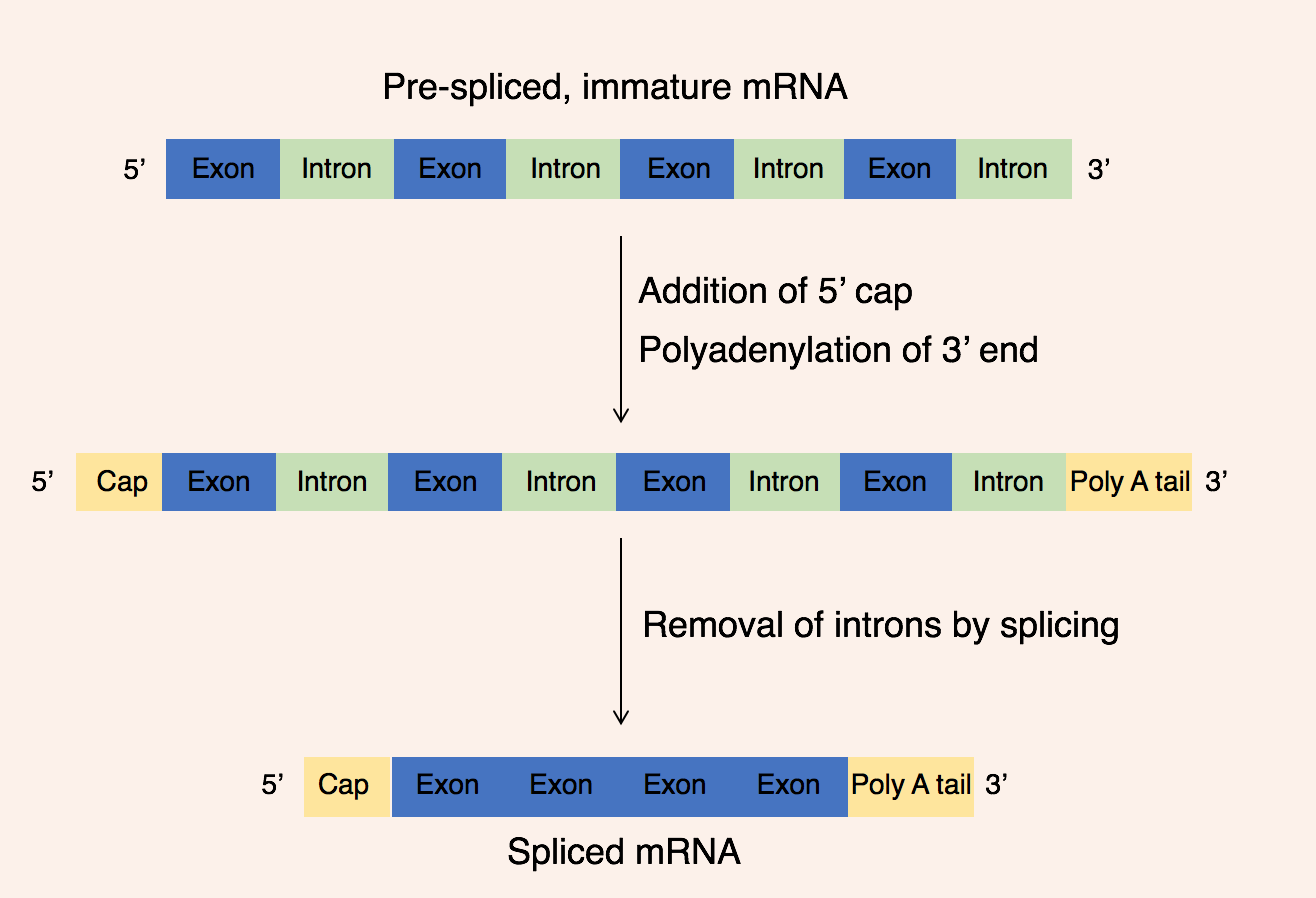

There are 3 key steps within post-transcriptional modifications:

# Addition of a 5' cap

In molecular biology, the five-prime cap (5′ cap) is a specially altered nucleotide on the 5′ end of some primary transcripts such as precursor messenger RNA. This process, known as mRNA capping, is highly regulated and vital in the creation o ...

to the 5' end of the pre-mRNA molecule

# Addition of a 3' poly(A) tail

Polyadenylation is the addition of a poly(A) tail to an RNA transcript, typically a messenger RNA (mRNA). The poly(A) tail consists of multiple adenosine monophosphates; in other words, it is a stretch of RNA that has only adenine bases. In euk ...

is added to the 3' end pre-mRNA molecule

# Removal of intron

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word ''intron'' is derived from the term ''intragenic region'', i.e. a region inside a gene."The notion of the cistron .e., gene. ...

s via RNA splicing

RNA splicing is a process in molecular biology where a newly-made precursor messenger RNA (pre-mRNA) transcript is transformed into a mature messenger RNA (mRNA). It works by removing all the introns (non-coding regions of RNA) and ''splicing'' b ...

The 5' cap is added to the 5' end of the pre-mRNA molecule and is composed of a guanine nucleotide modified through methylation

In the chemical sciences, methylation denotes the addition of a methyl group on a substrate, or the substitution of an atom (or group) by a methyl group. Methylation is a form of alkylation, with a methyl group replacing a hydrogen atom. These t ...

. The purpose of the 5' cap is to prevent break down of mature mRNA molecules before translation, the cap also aids binding of the ribosome to the mRNA to start translation and enables mRNA to be differentiated from other RNAs in the cell. In contrast, the 3' Poly(A) tail is added to the 3' end of the mRNA molecule and is composed of 100-200 adenine bases. These distinct mRNA modifications enable the cell to detect that the full mRNA message is intact if both the 5' cap and 3' tail are present.

This modified pre-mRNA molecule then undergoes the process of RNA splicing. Genes are composed of a series of introns and exon

An exon is any part of a gene that will form a part of the final mature RNA produced by that gene after introns have been removed by RNA splicing. The term ''exon'' refers to both the DNA sequence within a gene and to the corresponding sequen ...

s, introns are nucleotide sequences which do not encode a protein while, exons are nucleotide sequences that directly encode a protein. Introns and exons are present in both the underlying DNA sequence and the pre-mRNA molecule, therefore, in order to produce a mature mRNA molecule encoding a protein, splicing must occur. During splicing, the intervening introns are removed from the pre-mRNA molecule by a multi-protein complex known as a spliceosome

A spliceosome is a large ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex found primarily within the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. The spliceosome is assembled from small nuclear RNAs (snRNA) and numerous proteins. Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) molecules bind to specifi ...

(composed of over 150 proteins and RNA). This mature mRNA molecule is then exported into the cytoplasm through nuclear pores in the envelope of the nucleus.

Translation

During translation, ribosomes synthesize polypeptide chains from mRNA template molecules. In eukaryotes, translation occurs in the cytoplasm of the cell, where the ribosomes are located either free floating or attached to the

During translation, ribosomes synthesize polypeptide chains from mRNA template molecules. In eukaryotes, translation occurs in the cytoplasm of the cell, where the ribosomes are located either free floating or attached to the endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum ( ...

. In prokaryotes, which lack a nucleus, the processes of both transcription and translation occur in the cytoplasm.

Ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

s are complex molecular machine

A molecular machine, nanite, or nanomachine is a molecular component that produces quasi-mechanical movements (output) in response to specific stimuli (input). In cellular biology, macromolecular machines frequently perform tasks essential for l ...

s, made of a mixture of protein and ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosomal ...

, arranged into two subunits (a large and a small subunit), which surround the mRNA molecule. The ribosome reads the mRNA molecule in a 5'-3' direction and uses it as a template to determine the order of amino acids in the polypeptide chain. In order to translate the mRNA molecule, the ribosome uses small molecules, known as transfer RNA

Transfer RNA (abbreviated tRNA and formerly referred to as sRNA, for soluble RNA) is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes), that serves as the physical link between the mRNA and the amino ac ...

s (tRNA), to deliver the correct amino acids to the ribosome. Each tRNA is composed of 70-80 nucleotides and adopts a characteristic cloverleaf structure due to the formation of hydrogen bonds between the nucleotides within the molecule. There are around 60 different types of tRNAs, each tRNA binds to a specific sequence of three nucleotides (known as a codon

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

) within the mRNA molecule and delivers a specific amino acid.

The ribosome initially attaches to the mRNA at the start codon

The start codon is the first codon of a messenger RNA (mRNA) transcript translated by a ribosome. The start codon always codes for methionine in eukaryotes and Archaea and a N-formylmethionine (fMet) in bacteria, mitochondria and plastids. The ...

(AUG) and begins to translate the molecule. The mRNA nucleotide sequence is read in triplets

A multiple birth is the culmination of one multiple pregnancy, wherein the mother gives birth to two or more babies. A term most applicable to vertebrate species, multiple births occur in most kinds of mammals, with varying frequencies. Such bir ...

- three adjacent nucleotides in the mRNA molecule correspond to a single codon. Each tRNA has an exposed sequence of three nucleotides, known as the anticodon, which are complementary in sequence to a specific codon that may be present in mRNA. For example, the first codon encountered is the start codon composed of the nucleotides AUG. The correct tRNA with the anticodon (complementary 3 nucleotide sequence UAC) binds to the mRNA using the ribosome. This tRNA delivers the correct amino acid corresponding to the mRNA codon, in the case of the start codon, this is the amino acid methionine. The next codon (adjacent to the start codon) is then bound by the correct tRNA with complementary anticodon, delivering the next amino acid to ribosome. The ribosome then uses its peptidyl transferase

The peptidyl transferase is an aminoacyltransferase () as well as the primary enzymatic function of the ribosome, which forms peptide bonds between adjacent amino acids using tRNAs during the translation process of protein biosynthesis. The subst ...

enzymatic activity to catalyze the formation of the covalent peptide bond between the two adjacent amino acids.

The ribosome then moves along the mRNA molecule to the third codon. The ribosome then releases the first tRNA molecule, as only two tRNA molecules can be brought together by a single ribosome at one time. The next complementary tRNA with the correct anticodon complementary to the third codon is selected, delivering the next amino acid to the ribosome which is covalently joined to the growing polypeptide chain. This process continues with the ribosome moving along the mRNA molecule adding up to 15 amino acids per second to the polypeptide chain. Behind the first ribosome, up to 50 additional ribosomes can bind to the mRNA molecule forming a polysome

A polyribosome (or polysome or ergosome) is a group of ribosomes bound to an mRNA molecule like “beads” on a “thread”. It consists of a complex of an mRNA molecule and two or more ribosomes that act to translate mRNA instructions into po ...

, this enables simultaneous synthesis of multiple identical polypeptide chains. Termination of the growing polypeptide chain occurs when the ribosome encounters a stop codon (UAA, UAG, or UGA) in the mRNA molecule. When this occurs, no tRNA can recognise it and a release factor

A release factor is a protein that allows for the termination of translation by recognizing the termination codon or stop codon in an mRNA sequence. They are named so because they release new peptides from the ribosome.

Background

During t ...

induces the release of the complete polypeptide chain from the ribosome. Dr. Har Gobind Khorana

Har Gobind Khorana (9 January 1922 – 9 November 2011) was an Indian American biochemist. While on the faculty of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, he shared the 1968 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine with Marshall W. Nirenberg and ...

, a scientist originating from India, decoded the RNA sequences for about 20 amino acids. He was awarded the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

in 1968, along with two other scientists, for his work.

Protein folding

Once synthesis of the polypeptide chain is complete, the polypeptide chain folds to adopt a specific structure which enables the protein to carry out its functions. The basic form of

Once synthesis of the polypeptide chain is complete, the polypeptide chain folds to adopt a specific structure which enables the protein to carry out its functions. The basic form of protein structure

Protein structure is the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in an amino acid-chain molecule. Proteins are polymers specifically polypeptides formed from sequences of amino acids, the monomers of the polymer. A single amino acid monomer ma ...

is known as the primary structure

Protein primary structure is the linear sequence of amino acids in a peptide or protein. By convention, the primary structure of a protein is reported starting from the amino-terminal (N) end to the carboxyl-terminal (C) end. Protein biosynthes ...

, which is simply the polypeptide chain i.e. a sequence of covalently bonded amino acids. The primary structure of a protein is encoded by a gene. Therefore, any changes to the sequence of the gene can alter the primary structure of the protein and all subsequent levels of protein structure, ultimately changing the overall structure and function.

The primary structure of a protein (the polypeptide chain) can then fold or coil to form the secondary structure of the protein. The most common types of secondary structure are known as an alpha helix

The alpha helix (α-helix) is a common motif in the secondary structure of proteins and is a right hand-helix conformation in which every backbone N−H group hydrogen bonds to the backbone C=O group of the amino acid located four residues e ...

or beta sheet

The beta sheet, (β-sheet) (also β-pleated sheet) is a common motif of the regular protein secondary structure. Beta sheets consist of beta strands (β-strands) connected laterally by at least two or three backbone hydrogen bonds, forming a g ...

, these are small structures produced by hydrogen bonds forming within the polypeptide chain. This secondary structure then folds to produce the tertiary structure of the protein. The tertiary structure is the proteins overall 3D structure which is made of different secondary structures folding together. In the tertiary structure, key protein features e.g. the active site, are folded and formed enabling the protein to function. Finally, some proteins may adopt a complex quaternary structure

Protein quaternary structure is the fourth (and highest) classification level of protein structure. Protein quaternary structure refers to the structure of proteins which are themselves composed of two or more smaller protein chains (also refe ...

. Most proteins are made of a single polypeptide chain, however, some proteins are composed of multiple polypeptide chains (known as subunits) which fold and interact to form the quaternary structure. Hence, the overall protein is a multi-subunit complex composed of multiple folded, polypeptide chain subunits e.g. haemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

.

Post-translation events

There are events that follow protein biosynthesis such as proteolysis and protein-folding. Proteolysis refers to the cleavage of proteins by proteases and the breakdown of proteins into amino acids by the action of enzymes.Post-translational modifications

When protein folding into the mature, functional 3D state is complete, it is not necessarily the end of the protein maturation pathway. A folded protein can still undergo further processing through post-translational modifications. There are over 200 known types of post-translational modification, these modifications can alter protein activity, the ability of the protein to interact with other proteins and where the protein is found within the cell e.g. in the cell nucleus or cytoplasm. Through post-translational modifications, the diversity of proteins encoded by the genome is expanded by 2 to 3orders of magnitude

An order of magnitude is an approximation of the logarithm of a value relative to some contextually understood reference value, usually 10, interpreted as the base of the logarithm and the representative of values of magnitude one. Logarithmic dis ...

.

There are four key classes of post-translational modification:

# Cleavage

# Addition of chemical groups

# Addition of complex molecules

# Formation of intramolecular bonds

Cleavage

Cleavage of proteins is an irreversible post-translational modification carried out by enzymes known as

Cleavage of proteins is an irreversible post-translational modification carried out by enzymes known as proteases

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the for ...

. These proteases are often highly specific and cause hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution reaction, substitution, elimination reaction, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water ...

of a limited number of peptide bonds within the target protein. The resulting shortened protein has an altered polypeptide chain with different amino acids at the start and end of the chain. This post-translational modification often alters the proteins function, the protein can be inactivated or activated by the cleavage and can display new biological activities.

Addition of chemical groups

Following translation, small chemical groups can be added onto amino acids within the mature protein structure. Examples of processes which add chemical groups to the target protein include methylation,

Following translation, small chemical groups can be added onto amino acids within the mature protein structure. Examples of processes which add chemical groups to the target protein include methylation, acetylation

:

In organic chemistry, acetylation is an organic esterification reaction with acetic acid. It introduces an acetyl group into a chemical compound. Such compounds are termed ''acetate esters'' or simply '' acetates''. Deacetylation is the oppo ...

and phosphorylation

In chemistry, phosphorylation is the attachment of a phosphate group to a molecule or an ion. This process and its inverse, dephosphorylation, are common in biology and could be driven by natural selection. Text was copied from this source, wh ...

.

Methylation is the reversible addition of a methyl group

In organic chemistry, a methyl group is an alkyl derived from methane, containing one carbon atom bonded to three hydrogen atoms, having chemical formula . In formulas, the group is often abbreviated as Me. This hydrocarbon group occurs in many ...

onto an amino acid catalyzed by methyltransferase

Methyltransferases are a large group of enzymes that all methylate their substrates but can be split into several subclasses based on their structural features. The most common class of methyltransferases is class I, all of which contain a Rossm ...

enzymes. Methylation occurs on at least 9 of the 20 common amino acids, however, it mainly occurs on the amino acids lysine

Lysine (symbol Lys or K) is an α-amino acid that is a precursor to many proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the deprotonated −C ...

and arginine

Arginine is the amino acid with the formula (H2N)(HN)CN(H)(CH2)3CH(NH2)CO2H. The molecule features a guanidino group appended to a standard amino acid framework. At physiological pH, the carboxylic acid is deprotonated (−CO2−) and both the am ...

. One example of a protein which is commonly methylated is a histone

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes. Nucleosomes in turn are wr ...

. Histones are proteins found in the nucleus of the cell. DNA is tightly wrapped round histones and held in place by other proteins and interactions between negative charges in the DNA and positive charges on the histone. A highly specific pattern of amino acid methylation on the histone proteins is used to determine which regions of DNA are tightly wound and unable to be transcribed and which regions are loosely wound and able to be transcribed.

Histone-based regulation of DNA transcription is also modified by acetylation. Acetylation is the reversible covalent addition of an acetyl group

In organic chemistry, acetyl is a functional group with the chemical formula and the structure . It is sometimes represented by the symbol Ac (not to be confused with the element actinium). In IUPAC nomenclature, acetyl is called ethanoyl, ...

onto a lysine amino acid by the enzyme acetyltransferase

Acetyltransferase (or transacetylase) is a type of transferase enzyme that transfers an acetyl group.

Examples include:

* Histone acetyltransferases including CBP histone acetyltransferase

* Choline acetyltransferase

* Chloramphenicol acetyltransf ...

. The acetyl group is removed from a donor molecule known as acetyl coenzyme A

Acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A) is a molecule that participates in many biochemical reactions in protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Its main function is to deliver the acetyl group to the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) to be oxidized for ...

and transferred onto the target protein. Histones undergo acetylation on their lysine residues by enzymes known as histone acetyltransferase

Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) are enzymes that acetylate conserved lysine amino acids on histone proteins by transferring an acetyl group from acetyl-CoA to form ε-''N''-acetyllysine. DNA is wrapped around histones, and, by transferring an ...

. The effect of acetylation is to weaken the charge interactions between the histone and DNA, thereby making more genes in the DNA accessible for transcription.

The final, prevalent post-translational chemical group modification is phosphorylation. Phosphorylation is the reversible, covalent addition of a phosphate

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosphoric acid .

The phosphate or orthophosphate ion is derived from phospho ...

group to specific amino acids (serine

Serine (symbol Ser or S) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated − form under biological conditions), a carboxyl group (which is in the deprotonated − form un ...

, threonine

Threonine (symbol Thr or T) is an amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH form under biological conditions), a carboxyl group (which is in the deprotonated −COO� ...

and tyrosine

-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y) or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a non-essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is from the Gr ...

) within the protein. The phosphate group is removed from the donor molecule ATP by a protein kinase

In biochemistry, a kinase () is an enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of phosphate groups from high-energy, phosphate-donating molecules to specific substrates. This process is known as phosphorylation, where the high-energy ATP molecule don ...

and transferred onto the hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy ...

group of the target amino acid, this produces adenosine diphosphate

Adenosine diphosphate (ADP), also known as adenosine pyrophosphate (APP), is an important organic compound in metabolism and is essential to the flow of energy in living cells. ADP consists of three important structural components: a sugar backbon ...

as a biproduct. This process can be reversed and the phosphate group removed by the enzyme protein phosphatase

In biochemistry, a phosphatase is an enzyme that uses water to cleave a phosphoric acid Ester, monoester into a phosphate ion and an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol. Because a phosphatase enzyme catalysis, catalyzes the hydrolysis of its Substrate ...

. Phosphorylation can create a binding site on the phosphorylated protein which enables it to interact with other proteins and generate large, multi-protein complexes. Alternatively, phosphorylation can change the level of protein activity by altering the ability of the protein to bind its substrate.

Addition of complex molecules

Post-translational modifications can incorporate more complex, large molecules into the folded protein structure. One common example of this is

Post-translational modifications can incorporate more complex, large molecules into the folded protein structure. One common example of this is glycosylation

Glycosylation is the reaction in which a carbohydrate (or ' glycan'), i.e. a glycosyl donor, is attached to a hydroxyl or other functional group of another molecule (a glycosyl acceptor) in order to form a glycoconjugate. In biology (but not al ...

, the addition of a polysaccharide molecule, which is widely considered to be most common post-translational modification.

In glycosylation, a polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wa ...

molecule (known as a glycan

The terms glycans and polysaccharides are defined by IUPAC as synonyms meaning "compounds consisting of a large number of monosaccharides linked glycosidically". However, in practice the term glycan may also be used to refer to the carbohydrate p ...

) is covalently added to the target protein by glycosyltransferases

Glycosyltransferases (GTFs, Gtfs) are enzymes ( EC 2.4) that establish natural glycosidic linkages. They catalyze the transfer of saccharide moieties from an activated nucleotide sugar (also known as the "glycosyl donor") to a nucleophilic glycos ...

enzymes and modified by glycosidases

Glycoside hydrolases (also called glycosidases or glycosyl hydrolases) catalyze the hydrolysis of glycosidic bonds in complex sugars. They are extremely common enzymes with roles in nature including degradation of biomass such as cellulose (cel ...

in the endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is, in essence, the transportation system of the eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. It is a type of organelle made up of two subunits – rough endoplasmic reticulum ( ...

and Golgi apparatus

The Golgi apparatus (), also known as the Golgi complex, Golgi body, or simply the Golgi, is an organelle found in most eukaryotic cells. Part of the endomembrane system in the cytoplasm, it packages proteins into membrane-bound vesicles ins ...

. Glycosylation can have a critical role in determining the final, folded 3D structure of the target protein. In some cases glycosylation is necessary for correct folding. N-linked glycosylation promotes protein folding by increasing solubility

In chemistry, solubility is the ability of a substance, the solute, to form a solution with another substance, the solvent. Insolubility is the opposite property, the inability of the solute to form such a solution.

The extent of the solubil ...

and mediates the protein binding to protein chaperones. Chaperones are proteins responsible for folding and maintaining the structure of other proteins.

There are broadly two types of glycosylation, N-linked glycosylation

''N''-linked glycosylation, is the attachment of an oligosaccharide, a carbohydrate consisting of several sugar molecules, sometimes also referred to as glycan, to a nitrogen atom (the amide nitrogen of an asparagine (Asn) residue of a protein), ...

and O-linked glycosylation

''O''-linked glycosylation is the attachment of a sugar molecule to the oxygen atom of serine (Ser) or threonine (Thr) residues in a protein. ''O''-glycosylation is a post-translational modification that occurs after the protein has been synthesise ...

. N-linked glycosylation starts in the endoplasmic reticulum with the addition of a precursor glycan. The precursor glycan is modified in the Golgi apparatus to produce complex glycan bound covalently to the nitrogen in an asparagine

Asparagine (symbol Asn or N) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the depro ...

amino acid. In contrast, O-linked glycosylation is the sequential covalent addition of individual sugars onto the oxygen in the amino acids serine and threonine within the mature protein structure.

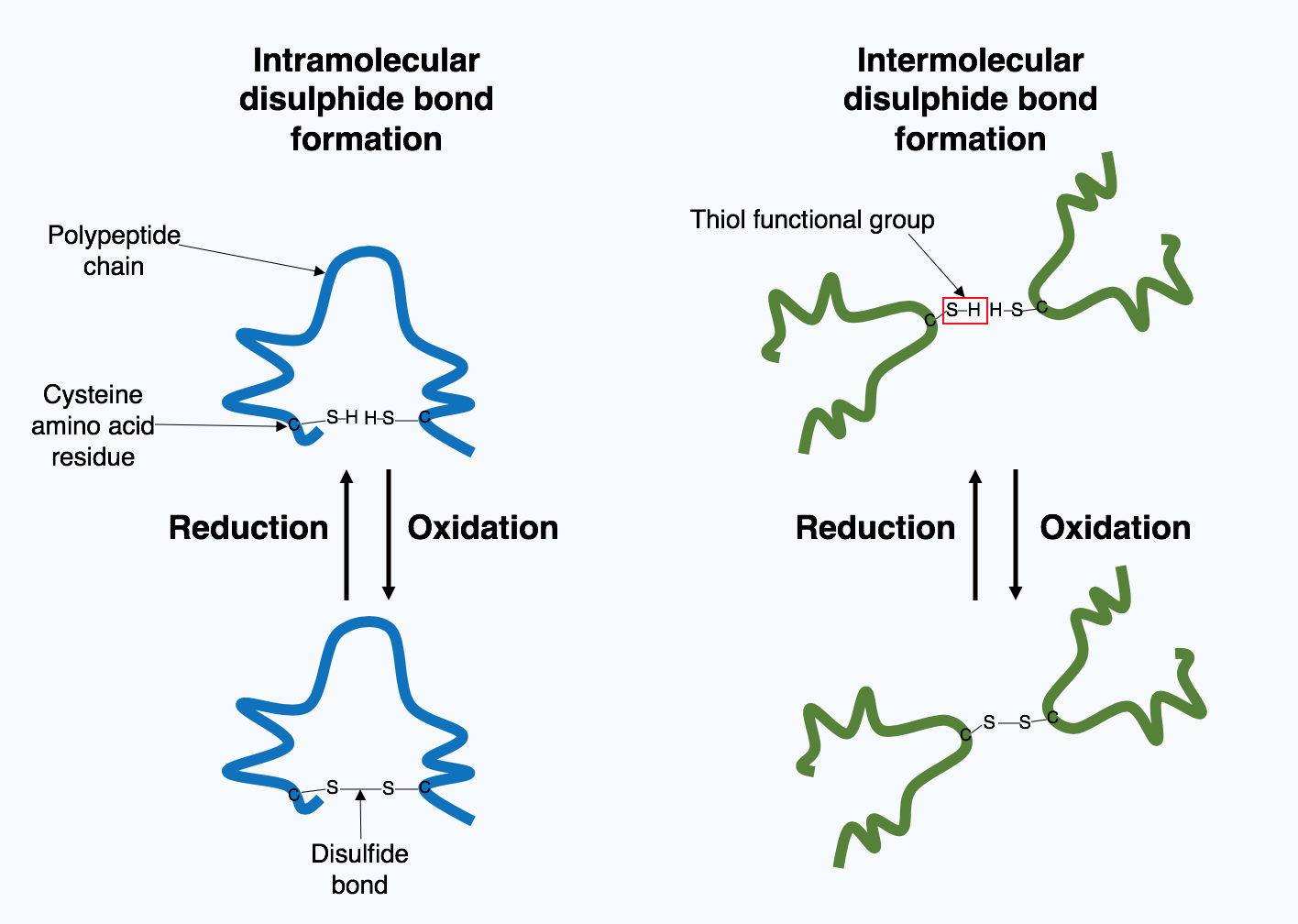

Formation of covalent bonds

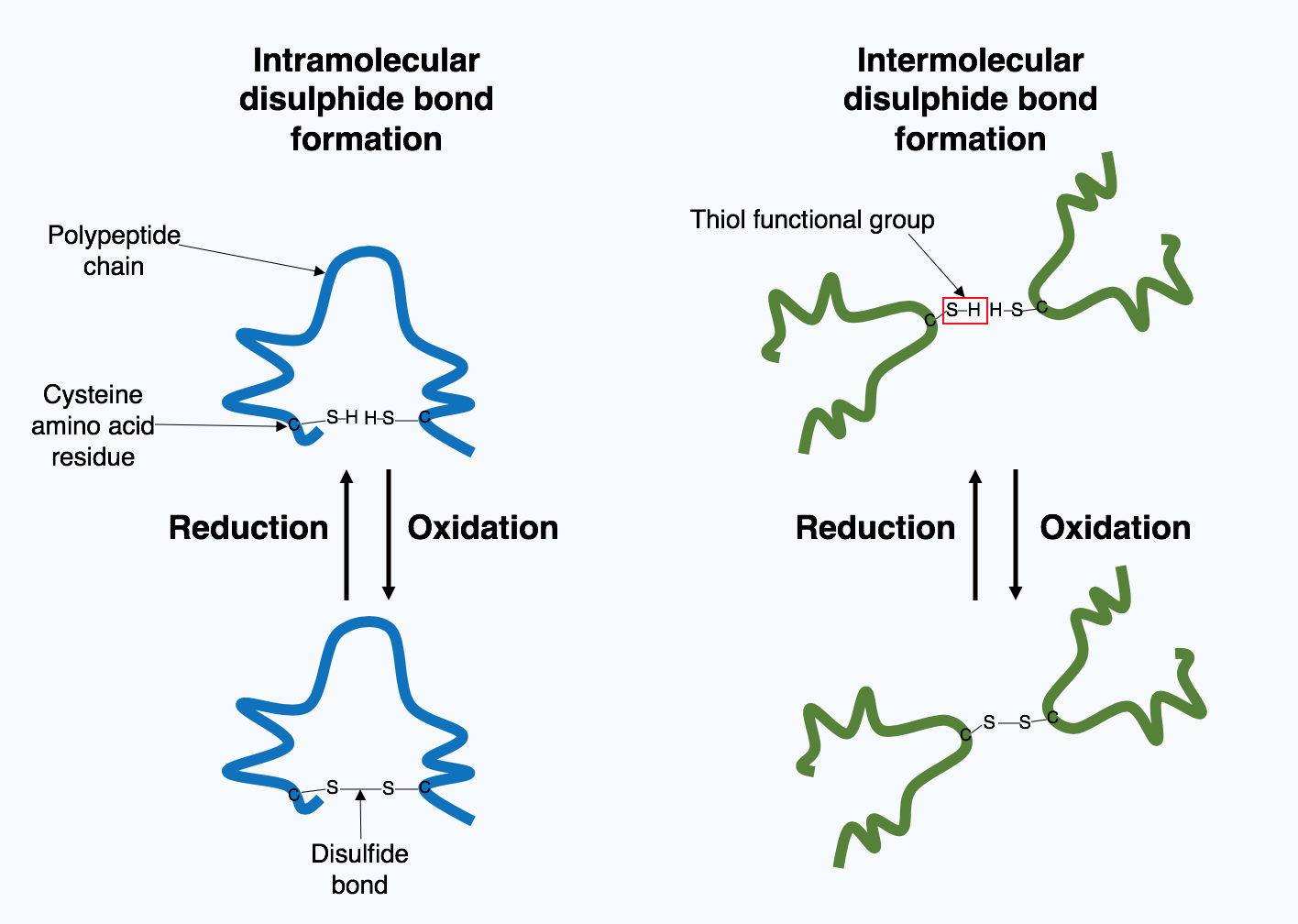

Many proteins produced within the cell are secreted outside the cell to function as

Many proteins produced within the cell are secreted outside the cell to function as extracellular

This glossary of biology terms is a list of definitions of fundamental terms and concepts used in biology, the study of life and of living organisms. It is intended as introductory material for novices; for more specific and technical definitions ...

proteins. Extracellular proteins are exposed to a wide variety of conditions. In order to stabilize the 3D protein structure, covalent bonds are formed either within the protein or between the different polypeptide chains in the quaternary structure. The most prevalent type is a disulfide bond

In biochemistry, a disulfide (or disulphide in British English) refers to a functional group with the structure . The linkage is also called an SS-bond or sometimes a disulfide bridge and is usually derived by the coupling of two thiol groups. In ...

(also known as a disulfide bridge). A disulfide bond is formed between two cysteine

Cysteine (symbol Cys or C; ) is a semiessential proteinogenic amino acid with the formula . The thiol side chain in cysteine often participates in enzymatic reactions as a nucleophile.

When present as a deprotonated catalytic residue, sometime ...

amino acids using their side chain chemical groups containing a Sulphur atom, these chemical groups are known as thiol

In organic chemistry, a thiol (; ), or thiol derivative, is any organosulfur compound of the form , where R represents an alkyl or other organic substituent. The functional group itself is referred to as either a thiol group or a sulfhydryl gro ...

functional groups. Disulfide bonds act to stabilize the pre-existing structure of the protein. Disulfide bonds are formed in an oxidation reaction

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a d ...

between two thiol groups and therefore, need an oxidizing environment to react. As a result, disulfide bonds are typically formed in the oxidizing environment of the endoplasmic reticulum catalyzed by enzymes called protein disulfide isomerases. Disulfide bonds are rarely formed in the cytoplasm as it is a reducing environment.

Role of protein synthesis in disease

Many diseases are caused by mutations in genes, due to the direct connection between the DNA nucleotide sequence and the amino acid sequence of the encoded protein. Changes to the primary structure of the protein can result in the protein mis-folding or malfunctioning. Mutations within a single gene have been identified as a cause of multiple diseases, includingsickle cell disease

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of blood disorders typically inherited from a person's parents. The most common type is known as sickle cell anaemia. It results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin found in red blo ...

, known as single gene disorders.

Sickle cell disease

Sickle cell disease is a group of diseases caused by a mutation in a subunit of hemoglobin, a protein found in red blood cells responsible for transporting oxygen. The most dangerous of the sickle cell diseases is known as sickle cell anemia. Sickle cell anemia is the most common homozygous recessive single gene disorder, meaning the affected individual must carry a mutation in both copies of the affected gene (one inherited from each parent) to experience the disease. Hemoglobin has a complex quaternary structure and is composed of four polypeptide subunits - two A subunits and two B subunits. Patients with sickle cell anemia have a missense or substitution mutation in the gene encoding the hemoglobin B subunit polypeptide chain. A missense mutation means the nucleotide mutation alters the overall codon triplet such that a different amino acid is paired with the new codon. In the case of sickle cell anemia, the most common missense mutation is a single nucleotide mutation from thymine to adenine in the hemoglobin B subunit gene. This changes codon 6 from encoding the amino acid glutamic acid to encoding valine.

This change in the primary structure of the hemoglobin B subunit polypeptide chain alters the functionality of the hemoglobin multi-subunit complex in low oxygen conditions. When red blood cells unload oxygen into the tissues of the body, the mutated haemoglobin protein starts to stick together to form a semi-solid structure within the red blood cell. This distorts the shape of the red blood cell, resulting in the characteristic "sickle" shape, and reduces cell flexibility. This rigid, distorted red blood cell can accumulate in blood vessels creating a blockage. The blockage prevents blood flow to tissues and can lead to tissue death which causes great pain to the individual.

Sickle cell disease is a group of diseases caused by a mutation in a subunit of hemoglobin, a protein found in red blood cells responsible for transporting oxygen. The most dangerous of the sickle cell diseases is known as sickle cell anemia. Sickle cell anemia is the most common homozygous recessive single gene disorder, meaning the affected individual must carry a mutation in both copies of the affected gene (one inherited from each parent) to experience the disease. Hemoglobin has a complex quaternary structure and is composed of four polypeptide subunits - two A subunits and two B subunits. Patients with sickle cell anemia have a missense or substitution mutation in the gene encoding the hemoglobin B subunit polypeptide chain. A missense mutation means the nucleotide mutation alters the overall codon triplet such that a different amino acid is paired with the new codon. In the case of sickle cell anemia, the most common missense mutation is a single nucleotide mutation from thymine to adenine in the hemoglobin B subunit gene. This changes codon 6 from encoding the amino acid glutamic acid to encoding valine.

This change in the primary structure of the hemoglobin B subunit polypeptide chain alters the functionality of the hemoglobin multi-subunit complex in low oxygen conditions. When red blood cells unload oxygen into the tissues of the body, the mutated haemoglobin protein starts to stick together to form a semi-solid structure within the red blood cell. This distorts the shape of the red blood cell, resulting in the characteristic "sickle" shape, and reduces cell flexibility. This rigid, distorted red blood cell can accumulate in blood vessels creating a blockage. The blockage prevents blood flow to tissues and can lead to tissue death which causes great pain to the individual.

Cancer

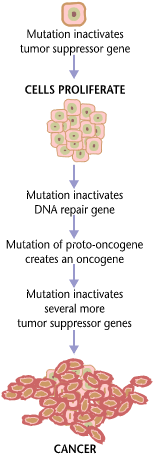

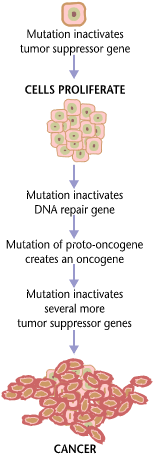

Cancers form as a result of gene mutations as well as improper protein translation. In addition to cancer cells proliferating abnormally, they suppress the expression of anti-apoptotic or pro-apoptotic genes or proteins. Most cancer cells see a mutation in the signaling protein Ras, which functions as an on/off signal transductor in cells. In cancer cells, the RAS protein becomes persistently active, thus promoting the proliferation of the cell due to the absence of any regulation. Additionally, most cancer cells carry two mutant copies of the regulator gene p53, which acts as a gatekeeper for damaged genes and initiates apoptosis in malignant cells. In its absence, the cell cannot initiate apoptosis or signal for other cells to destroy it.

As the tumor cells proliferate, they either remain confined to one area and are called benign, or become malignant cells that migrate to other areas of the body. Oftentimes, these malignant cells secrete proteases that break apart the extracellular matrix of tissues. This then allows the cancer to enter its terminal stage called Metastasis, in which the cells enter the bloodstream or the lymphatic system to travel to a new part of the body.

Cancers form as a result of gene mutations as well as improper protein translation. In addition to cancer cells proliferating abnormally, they suppress the expression of anti-apoptotic or pro-apoptotic genes or proteins. Most cancer cells see a mutation in the signaling protein Ras, which functions as an on/off signal transductor in cells. In cancer cells, the RAS protein becomes persistently active, thus promoting the proliferation of the cell due to the absence of any regulation. Additionally, most cancer cells carry two mutant copies of the regulator gene p53, which acts as a gatekeeper for damaged genes and initiates apoptosis in malignant cells. In its absence, the cell cannot initiate apoptosis or signal for other cells to destroy it.

As the tumor cells proliferate, they either remain confined to one area and are called benign, or become malignant cells that migrate to other areas of the body. Oftentimes, these malignant cells secrete proteases that break apart the extracellular matrix of tissues. This then allows the cancer to enter its terminal stage called Metastasis, in which the cells enter the bloodstream or the lymphatic system to travel to a new part of the body.

See also

*Central dogma of molecular biology

The central dogma of molecular biology is an explanation of the flow of genetic information within a biological system. It is often stated as "DNA makes RNA, and RNA makes protein", although this is not its original meaning. It was first stated by ...

*Genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

*Gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect. The ...

*Post-translational modification

Post-translational modification (PTM) is the covalent and generally enzymatic modification of proteins following protein biosynthesis. This process occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and the golgi apparatus. Proteins are synthesized by ribosome ...

*Protein folding

Protein folding is the physical process by which a protein chain is translated to its native three-dimensional structure, typically a "folded" conformation by which the protein becomes biologically functional. Via an expeditious and reproduci ...

References

External links

A useful video visualising the process of converting DNA to protein via transcription and translation

Video visualising the process of protein folding from the non-functional primary structure to a mature, folded 3D protein structure with reference to the role of mutations and protein mis-folding in disease

A more advanced video detailing the different types of post-translational modifications and their chemical structures

{{Authority control Gene expression Proteins Biosynthesis Metabolism