Protectorate Bohemia and Moravia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially

The population of the protectorate was mobilized for labor that would aid the German war effort, and special offices were organized to supervise the management of industries important to that effort. The Germans drafted Czechs to work in coal mines, in the iron and steel industry, and in armaments production. Consumer-goods production, much diminished, was largely directed toward supplying the German armed forces. The protectorate's population was subjected to rationing. The Czech crown was devalued to the ''Reichsmark'' at the rate of 10 crowns to 1 ''Reichsmark'', through actual rate should have been 6 crowns for 1 ''Reichsmark'', a policy that allowed the Germans to buy everything on the cheap in the protectorate. Inflation was a major problem throughout the existence of the protectorate, which was made worse by the refusal of the German authorities to raise wages to keep up with inflation, making the era a period of decreasing living standards as the crowns brought less and less. Even members of the ''volksdeutsche'' (ethnic Germans) living in the protectorate complained their living standards had been higher under Czechoslovakia, which was quite a surprise to most of them, who expected their living standards to rise under German rule.

German rule was moderate by Nazi standards during the first months of the occupation. The Czech government and political system, reorganized by Hácha, continued in formal existence. The

The population of the protectorate was mobilized for labor that would aid the German war effort, and special offices were organized to supervise the management of industries important to that effort. The Germans drafted Czechs to work in coal mines, in the iron and steel industry, and in armaments production. Consumer-goods production, much diminished, was largely directed toward supplying the German armed forces. The protectorate's population was subjected to rationing. The Czech crown was devalued to the ''Reichsmark'' at the rate of 10 crowns to 1 ''Reichsmark'', through actual rate should have been 6 crowns for 1 ''Reichsmark'', a policy that allowed the Germans to buy everything on the cheap in the protectorate. Inflation was a major problem throughout the existence of the protectorate, which was made worse by the refusal of the German authorities to raise wages to keep up with inflation, making the era a period of decreasing living standards as the crowns brought less and less. Even members of the ''volksdeutsche'' (ethnic Germans) living in the protectorate complained their living standards had been higher under Czechoslovakia, which was quite a surprise to most of them, who expected their living standards to rise under German rule.

German rule was moderate by Nazi standards during the first months of the occupation. The Czech government and political system, reorganized by Hácha, continued in formal existence. The  During

During

After the establishment of the Protectorate all political parties were outlawed, with the exception of the

After the establishment of the Protectorate all political parties were outlawed, with the exception of the

The Czech State President (Státní Prezident) under the period of German rule from 1939 to 1945 was

The Czech State President (Státní Prezident) under the period of German rule from 1939 to 1945 was

The area of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia contained about 7,380,000 inhabitants in 1940. 225,000 (3.3%) of these were of German origin, while the rest were mainly ethnic

The area of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia contained about 7,380,000 inhabitants in 1940. 225,000 (3.3%) of these were of German origin, while the rest were mainly ethnic

* * * * * Further reading * *

Maps of the Protectorate Bohemia and Moravia

* * ttp://terkepek.adatbank.transindex.ro/kepek/netre/198.gif Hungarian language map with land transfers by Germany, Hungary, and Poland in the late 1930s.

Maps of Europe

showing the breakup of Czechoslovakia and the creation of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia at omniatlas.com

State Secretary in the Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia 1939–1945

German State Ministry of Bohemia and Moravia 1939–1945

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bohemia and Moravia, Protectorate of

annexed

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

territory of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

established on 16 March 1939 following the German occupation of the Czech lands. The protectorate's population was mostly ethnic Czech.

After the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

of September 1938, Germany had annexed the German-majority Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

from Czechoslovakia. Following the establishment of the independent Slovak Republic

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

on 14 March 1939, and the German occupation of the Czech rump state the next day, German leader Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

established the protectorate on 16 March 1939 by a proclamation from Prague Castle. The creation of the protectorate violated the Munich Agreement.Crowhurst, Patrick (2020) ''Hitler and Czechoslovakia in World War II: Domination and Retaliation''. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 96, .

The protectorate was nominally autonomous and had a dual system of government, with German law applying to ethnic Germans while other residents had the legal status of Protectorate subject and were governed by a puppet Czech administration. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the well-trained Czech workforce and developed industry was forced to make a major contribution to the German war economy. Since the Protectorate was just out of the reach of Allied bombers

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, the Czech economy was able to work almost undisturbed until the end of the war. The Protectorate administration was deeply involved in the Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia

The Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia resulted in the deportation, dispossession, and murder of most of the pre-World War II population of Jews in the Czech lands that were annexed by Nazi Germany.

Before the Holocaust, the Jews of Bohemia were ...

.

The state's existence came to an end with the surrender of Germany to the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

in 1945. After the war, some Protectorate officials were charged with collaborationism but according to the prevailing belief in Czech society, the Protectorate was not entirely rejected as a collaborationist entity.

Background

Hitler's interest in Czechoslovakia was largely driven by economic demands. The Four-Year Plan that Hitler launched in September 1936 to have the German economy ready for a "total war" by 1940 was faltering by 1937 owing to a shortage of foreign exchange to pay for the vast economic demands imposed by the ambitious armaments targets as Germany lacked many of the necessary raw materials, which had to be imported. The British historian Richard Overy wrote the huge demands of the Four Year Plan "...could not be fully met by a policy of import substitution and industrial rationalization".. In November 1937 at the Hossbach conference, Hitler announced that to stay ahead in the arms race with the other powers that Germany had to seize Czechoslovakia in the very near-future. Czechoslovakia was the world's 7th largest manufacturer of arms, making Czechoslovakia into an important player in the global arms trade. After Czechoslovakia was forced to accept the terms of theMunich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

of 30 September 1938, Nazi Germany incorporated the ethnic German majority Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

regions along the German border directly into Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. Five months later, the Nazis violated the Munich Agreement, when, with Nazi German support, the Slovak parliament declared the independence of the Slovak Republic

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

invited Czechoslovak President Emil Hácha

Emil Dominik Josef Hácha (12 July 1872 – 27 June 1945) was a Czech lawyer, the president of Czechoslovakia from November 1938 to March 1939. In March 1939, after the breakup of Czechoslovakia, Hácha was the nominal president of the newly pro ...

to Berlin and accepted his request for the German occupation of the Czech rump state and its reorganization as a German protectorate to deter Polish and Hungarian aggression.

Hitler's wish to occupy Czechoslovakia was largely caused by the foreign exchange crisis as Germany had exhausted its foreign exchange reserves by early 1939, and Germany urgently needed to seize the gold of the Czechoslovak central bank to continue the Four Year Plan. The British historian Victor Rothwell wrote that the Czechoslovak reserves of gold and hard currency seized in March 1939 were "invaluable in staving off Germany's foreign exchange crisis".

On 16 March when Hitler proclaimed the protectorate, he declared: “For a thousand years the provinces of Bohemia and Moravia formed part of the ''Lebensraum

(, ''living space'') is a German concept of settler colonialism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' became a geopolitical goal of Imperi ...

'' of the German people.”

There was no real precedent for this action in German history. The model for the protectorate were the Princely states in India under the Raj. In just in the same way that Indian maharajahs in the Princely states were allowed a nominal independence, but the real power rested with the British resident stationed to monitor the maharajah, Hitler emulated this practice with the Protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia as the German media quite explicitly compared the relationship between the Reich Protector, Baron Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin Hermann Karl Freiherr von Neurath (2 February 1873 – 14 August 1956) was a German diplomat and Nazi war criminal who served as Foreign Minister of Germany between 1932 and 1938.

Born to a Swabian noble family, Neurath began his di ...

and President Emil Hacha

Emil or Emile may refer to:

Literature

*'' Emile, or On Education'' (1762), a treatise on education by Jean-Jacques Rousseau

* ''Émile'' (novel) (1827), an autobiographical novel based on Émile de Girardin's early life

*'' Emil and the Detecti ...

to that of a British resident and an Indian maharajah. Neurath seems to be chosen as Reich Protector in because as a former foreign minister and a former ambassador to Great Britain, he was well known in London for his avuncular, but dignified manner, which were the personality traits associated with the popular image of a British resident. Hitler believed that emulating the Raj would accept this violation of the Munich Agreement more acceptable to Britain, and as that proved not to be the case the German media launched a lengthy campaign denouncing British "hypocrisy". The German authorities intentionally allowed the protectorate "all the trappings of independence" in order to encourage the Czech inhabitants to collaborate with them. However, despite the protectorate having its own postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper issued by a post office, postal administration, or other authorized vendors to customers who pay postage (the cost involved in moving, insuring, or registering mail), who then affix the stamp to the fa ...

s and presidential guard

Presidential Guard may refer to:

*President Guard Regiment (Bangladesh)

*Presidential Guard Regiment (Turkey)

*Presidential Guard (Greece)

*Presidential Guard (Belarus)

*Presidential Guard (South Vietnam)

*President's Own Guard Regiment (Ghana)

* ...

, real power lay with the Nazi authorities.

History

The population of the protectorate was mobilized for labor that would aid the German war effort, and special offices were organized to supervise the management of industries important to that effort. The Germans drafted Czechs to work in coal mines, in the iron and steel industry, and in armaments production. Consumer-goods production, much diminished, was largely directed toward supplying the German armed forces. The protectorate's population was subjected to rationing. The Czech crown was devalued to the ''Reichsmark'' at the rate of 10 crowns to 1 ''Reichsmark'', through actual rate should have been 6 crowns for 1 ''Reichsmark'', a policy that allowed the Germans to buy everything on the cheap in the protectorate. Inflation was a major problem throughout the existence of the protectorate, which was made worse by the refusal of the German authorities to raise wages to keep up with inflation, making the era a period of decreasing living standards as the crowns brought less and less. Even members of the ''volksdeutsche'' (ethnic Germans) living in the protectorate complained their living standards had been higher under Czechoslovakia, which was quite a surprise to most of them, who expected their living standards to rise under German rule.

German rule was moderate by Nazi standards during the first months of the occupation. The Czech government and political system, reorganized by Hácha, continued in formal existence. The

The population of the protectorate was mobilized for labor that would aid the German war effort, and special offices were organized to supervise the management of industries important to that effort. The Germans drafted Czechs to work in coal mines, in the iron and steel industry, and in armaments production. Consumer-goods production, much diminished, was largely directed toward supplying the German armed forces. The protectorate's population was subjected to rationing. The Czech crown was devalued to the ''Reichsmark'' at the rate of 10 crowns to 1 ''Reichsmark'', through actual rate should have been 6 crowns for 1 ''Reichsmark'', a policy that allowed the Germans to buy everything on the cheap in the protectorate. Inflation was a major problem throughout the existence of the protectorate, which was made worse by the refusal of the German authorities to raise wages to keep up with inflation, making the era a period of decreasing living standards as the crowns brought less and less. Even members of the ''volksdeutsche'' (ethnic Germans) living in the protectorate complained their living standards had been higher under Czechoslovakia, which was quite a surprise to most of them, who expected their living standards to rise under German rule.

German rule was moderate by Nazi standards during the first months of the occupation. The Czech government and political system, reorganized by Hácha, continued in formal existence. The Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

directed its activities mainly against Czech politicians and the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

. In 1940, in a secret plan on Germanization of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, it was declared that those considered to be racially Mongoloid and the Czech intelligentsia were not to be Germanized, and that about half of the Czech population were suitable for Germanization. Generalplan Ost assumed that around 50% of Czechs would be fit for Germanization. The Czech intellectual élites were to be removed from Czech territories and from Europe completely. The authors of Generalplan Ost believed it would be best if they emigrated overseas, as even in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

, they were considered a threat to German rule. Just like Jews, Poles, Serbs, and several other nations, Czechs were considered to be '' Untermenschen'' by the Nazi state. The Czechs however, were not subjected to a similar degree of random and organized acts of brutality that their Polish counterparts experienced. This is attributed to the view within the Nazi hierarchy that a large swath of the populace was "capable of Aryanization", such capacity for Aryanization was supported by the position that part of the Czech population had German ancestry. There is also the fact that a relatively restrained policy in Czech lands was partly driven by the need to keep the population nourished and complacent so that it can carry out the vital work of arms production in the factories. By 1939, the country was already serving as a major hub of military production for Germany, manufacturing aircraft, tanks, artillery, and other armaments.

The Czechs demonstrated against the occupation on 28 October 1939, the 21st anniversary of Czechoslovak independence. The death on 15 November 1939 of a medical student, Jan Opletal

Jan Opletal (1 January 1915 – 11 November 1939) was a student of the Medical Faculty of the Charles University in Prague, who was shot at a Czechoslovak declaration of independence, Czechoslovak Independence Day rally on 28 October 1939. He ...

, who had been wounded in the October violence, precipitated widespread student demonstrations, and the Germans retaliated. Politicians were arrested ''en masse'', as were an estimated 1,800 students and teachers. On 17 November, all universities and colleges in the protectorate were closed, nine student leaders were executed, and 1,200 were sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp within Nazi Germany; further arrests and executions of Czech students and professors took place later during the occupation. (''See also Czech resistance to Nazi occupation

Resistance to the German occupation of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia during World War II began after the occupation of the rest of Czechoslovakia and the formation of the protectorate on 15 March 1939. German policy deterred acts of ...

'')

During

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Hitler decided that Neurath was not treating the Czechs harshly enough and adopted a more radical policy in the protectorate. On 29 September 1941, Hitler appointed SS hardliner Reinhard Heydrich as Deputy ''Reichsprotektor'' (''Stellvertretender Reichsprotektor''). At the same time, he relieved Neurath of his day-to-day duties. For all intents and purposes, Heydrich replaced Neurath as ''Reichsprotektor''. Under Heydrich's authority Prime Minister Alois Eliáš was arrested (and later executed), the Czech government was reorganized, and all Czech cultural organizations were closed. The Gestapo arrested and murdered people. The deportation of Jews to concentration camps was organized, and the fortress town of Terezín was made into a ghetto way-station for Jewish families.

On 4 June 1942, Heydrich died after being wounded by Czechoslovak Commandos in Operation Anthropoid

On 27 May 1942 in Prague, Reinhard Heydrichthe commander of the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA), acting governor of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, and a principal architect of the Holocaustwas attacked and wounded in an assassinatio ...

. Directives issued by Heydrich's successor, SS-'' Oberstgruppenführer'' Kurt Daluege, and martial law brought forth mass arrests, executions and the obliteration of the villages of Lidice and Ležáky. In 1943 the German war-effort was accelerated. Under the authority of Karl Hermann Frank, German minister of state for Bohemia and Moravia, within the protectorate, all non-war-related industry was prohibited. Most of the Czech population obeyed quietly until the final months preceding the end of the war, when thousands became involved in the resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized effort by some portion of the civil population of a country to withstand the legally established government or an occupying power and to disrupt civil order and stability. It may seek to achieve its objective ...

.

For the Czechs of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, German occupation

German-occupied Europe refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly occupied and civil-occupied (including puppet governments) by the military forces and the government of Nazi Germany at various times between 1939 an ...

represented a period of oppression

Oppression is malicious or unjust treatment or exercise of power, often under the guise of governmental authority or cultural opprobrium. Oppression may be overt or covert, depending on how it is practiced. Oppression refers to discrimination w ...

. The number of Czech victims of political persecution and murders in concentration camps totalled between 36,000 and 55,000.Agnew, Hugh LeCainer (2004) ''The Czechs and the Lands of the Bohemian Crown''. Hoover Press. p. 215, . After Heydrich assumed control of the Protectorate, he instituted martial law and stepped up arrests and executions of resistance fighters. Heydrich allegedly referred to Czechs as "laughing beasts," reflecting Czech subversion and Nazi racial beliefs about the inferiority of Czechs.

The Jewish population of Bohemia and Moravia (118,000 according to the 1930 census) was virtually annihilated, with over 75,000 murdered. Of the 92,199 people classified as Jews by German authorities in the Protectorate as of 1939, 78,154 were murdered in the Holocaust, or 85 percent.

Many Jews emigrated after 1939; 8,000 survived at the Terezín concentration camp, which was used for propaganda purposes as a showpiece. Several thousand Jews managed to live in freedom or in hiding throughout the occupation. The extermination of the Romani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnicities

* Romani people, an ethnic group of Northern Indian origin, living dispersed in Europe, the Americas and Asia

** Romani genocide, under Nazi rule

* Romani language, any of several Indo-Aryan languages of the Roma ...

population was so thorough that the Bohemian Romani

Bohemian Romani or ''Bohemian Romany'' is a dialect of Romani formerly spoken by the Romani people of Bohemia, the western part of today's Czech Republic. It became extinct after World War II, due to extermination of most of its speakers in Nazi ...

language became totally extinct. Romani internees were sent to the Lety and Hodonín concentration camps before being transferred to Auschwitz-Birkenau

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

for gassing. The vast majority of Romani in the Czech Republic today descend from migrants from Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

who moved there within post-war Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. The Theresienstadt concentration camp

Theresienstadt Ghetto was established by the Schutzstaffel, SS during World War II in the fortress town of Terezín, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia (German occupation of Czechoslovakia, German-occupied Czechoslovakia). Theresienstad ...

was located in the Protectorate, near the border to the Reichsgau Sudetenland

The Reichsgau Sudetenland was an administrative division of Nazi Germany from 1939 to 1945. It comprised the northern part of the ''Sudetenland'' territory, which was annexed from Czechoslovakia according to the 30 September 1938 Munich Agreement. ...

. It was designed to concentrate the Jewish population from the Protectorate and gradually move them to extermination camps, and it also held Western European and German Jews. While not an extermination camp itself, the harsh and unhygienic conditions still resulted in the death of 33,000 of the 140,000 Jews brought to the camp while a further 88,000 were sent to extermination camps, and only 19,000 survived.

Politics

After the establishment of the Protectorate all political parties were outlawed, with the exception of the

After the establishment of the Protectorate all political parties were outlawed, with the exception of the National Partnership

german: Nationale Gemeinschaft

, native_name_lang = Czech and German

, lang1 = de

, name_lang1 =

, lang2 =

, name_lang2 =

, lang3 =

, name_lang3 =

, lang4 =

, name_lang4 =

, logo =

, logo_size =

, caption =

, colorcode =

, a ...

(''Národní souručenství''). Membership of the ''Národní souručenství'' was closed to women and Jews. In the spring of 1939, about 2,130,000 men joined the group, amounting to between 98%-99% of the Czech male population. However, much of the registration for the ''Národní souručenství'' was done in the style of a census (a traditional outlet for nationalist feeling in the Czech lands), and the messages advocating joining the ''Národní souručenství'' emphasized that the group existed to affirm the Czech character of Bohemia-Moravia.

One spy for the government-in-exile in London reported: "The original, observable chaos and later fear of Gestapo informants and uncertainty has changed to courage and hope. The nation is coming together, not only in the National Solidarity Movement, which the majority did only to avoid losing our national existence, but individuals are coming together and one begins to feel if the nation has a backbone again". This local Czech Fascist party was led by a ruling Presidium until 1942, after which a Vůdce (Leader) for the party was appointed.

German government

Ultimate authority within the Protectorate was held by the ReichProtector

Protector(s) or The Protector(s) may refer to:

Roles and titles

* Protector (title), a title or part of various historical titles of heads of state and others in authority

** Lord Protector, a title that has been used in British constitutional la ...

(''Reichsprotektor''), the area's senior Nazi administrator, whose task it was to represent the interests of the German state. The office and title were held by a variety of persons during the Protectorate's existence. In succession these were:

* 16 March 1939–20 August 1943:

Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin Hermann Karl Freiherr von Neurath (2 February 1873 – 14 August 1956) was a German diplomat and Nazi war criminal who served as Foreign Minister of Germany between 1932 and 1938.

Born to a Swabian noble family, Neurath began his di ...

, former Foreign Minister of Nazi Germany (1932–1938) and Minister without Portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister who does not head a particular ministry. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet w ...

(1938–1945). He was placed on leave in September 1941 after Hitler's dissatisfaction with his "soft policies", although he still held the title of ''Reichsprotektor'' until his official resignation in August 1943.

* 27 September 1941–30 May 1942:

Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the ''SS-Reichssicherheitshauptamt'' (Reich Security Main Office

The Reich Security Main Office (german: Reichssicherheitshauptamt or RSHA) was an organization under Heinrich Himmler in his dual capacity as ''Chef der Deutschen Polizei'' (Chief of German Police) and ''Reichsführer-SS'', the head of the Nazi ...

) or RSHA. He was officially only a deputy to Neurath, but in reality was granted supreme authority over the entire state apparatus of the Protectorate.

* 31 May 1942–20 August 1943:

Kurt Daluege, Chief of the ''Ordnungspolizei

The ''Ordnungspolizei'' (), abbreviated ''Orpo'', meaning "Order Police", were the uniformed police force in Nazi Germany from 1936 to 1945. The Orpo organisation was absorbed into the Nazi monopoly on power after regional police jurisdiction w ...

'' (Order Police) or Orpo, in the Interior Ministry, who was also officially a deputy Reich Protector.

* 20 August 1943–5 May 1945:

Wilhelm Frick, former Minister of the Interior (1933–1943) and Minister without Portfolio (1943–1945).

Next to the Reich Protector there was also a political office of State Secretary (from 1943 known as the State Minister to the Reich Protector) who handled most of the internal security. From 1939 to 1945 this person was Karl Hermann Frank the senior SS and Police Leader in the Protectorate. A command of the '' Allgemeine-SS'' was also established, known as the SS-Oberabschnitt Böhmen-Mähren. The command was an active unit of the General-SS, technically the only such unit to exist outside of Germany, since most other Allgemeine-SS units in occupied or conquered countries were largely paper commands.

Czech government

The Czech State President (Státní Prezident) under the period of German rule from 1939 to 1945 was

The Czech State President (Státní Prezident) under the period of German rule from 1939 to 1945 was Emil Hácha

Emil Dominik Josef Hácha (12 July 1872 – 27 June 1945) was a Czech lawyer, the president of Czechoslovakia from November 1938 to March 1939. In March 1939, after the breakup of Czechoslovakia, Hácha was the nominal president of the newly pro ...

(1872–1945), who had been the President of the Second Czechoslovak Republic

The Second Czechoslovak Republic ( cs, Druhá československá republika, sk, Druhá česko-slovenská republika) existed for 169 days, between 30 September 1938 and 15 March 1939. It was composed of Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and ...

since November 1938. Rudolf Beran

Rudolf Beran (28 December 1887, in Pracejovice, Strakonice District – 23 April 1954, in Leopoldov Prison) was a Czechoslovak politician who served as prime minister of the country before its occupation by Nazi Germany and shortly thereafter, bef ...

(1887–1954) continued to hold the office of Minister President (Předseda vlády) after the German take-over. He was replaced by Alois Eliáš on 27 April 1939, who was himself also sacked on 2 October 1941 not long after the appointment of Reinhard Heydrich as the new Reich Protector. Because of his contacts with the Czechoslovak Government-in-Exile Eliáš was sentenced to death, and the execution was carried out on 19 June 1942 shortly after Heydrich's own death

Ownership is the state or fact of legal possession and control over property, which may be any asset, tangible or intangible. Ownership can involve multiple rights, collectively referred to as title, which may be separated and held by different ...

. From 19 January 1942 the government was led by Jaroslav Krejčí, and from January to May 1945 by Richard Bienert

Richard Bienert (September 5, 1881 – February 2, 1949) was a Czech high-ranking police officer and politician. He served as prime minister of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia from January 19 to May 5, 1945. After World War II he was senten ...

, the former police chief of Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

. When the dissolution of the Protectorate was proclaimed after the Liberation of Prague, a radio call was issued for Bienert's arrest. This resulted in his conviction to a three-year prison term in 1947, during which he died in 1949.

Aside from the Office of the Minister President, the local Czech government in the Protectorate consisted of the Ministries of Education, Finance, Justice, Trade, the Interior, Agriculture, and Public Labour. The area's foreign policy and military defence were under the exclusive control of the German government. The former foreign minister of Czechoslovakia František Chvalkovský

František Chvalkovský (30 July 1885, Jílové u Prahy – 25 February 1945) was a Czech diplomat and the fourth foreign minister of Czechoslovakia.

Activities during the First Republic

In the newly-independent Czechoslovakia, Chvalkovský fir ...

became a Minister without Portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister who does not head a particular ministry. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet w ...

and permanent representative of the Czech administration in Berlin.

The most prominent Czech politicians in the Protectorate included:

Population

Czechs

The Czechs ( cs, Češi, ; singular Czech, masculine: ''Čech'' , singular feminine: ''Češka'' ), or the Czech people (), are a West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common ancestry, c ...

as well as some Slovaks

The Slovaks ( sk, Slováci, singular: ''Slovák'', feminine: ''Slovenka'', plural: ''Slovenky'') are a West Slavic ethnic group and nation native to Slovakia who share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovak.

In Slovakia, 4.4 mi ...

, particularly near the border with Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

. Ethnic Germans were offered Reich citizenship, while Jews and Czechs were from the outset second-class citizens ("Protectorate subjects", german: Protektoratsangehörige).

In March 1939, Karl Frank defined a "German national" as:

The Nazis aimed for the protectorate to become fully Germanized

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, people and culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationalism went hand in hand. In ling ...

. Marriages between Czechs and Germans became a problem for the Nazis. In 1939, the Nazis did not ban sexual relations between Germans and Czechs and no law prohibited Jews from marrying Czechs. The Nazis made German women who married any non-Germans lose their Reich citizenship whereas Czech women who married German men were accepted into the German ''Volk''. Czech families aiming to improve their lives in the protectorate encouraged their Czech daughters to marry German men as it was one way to save a family business.

Hitler had approved a plan designed by Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin Hermann Karl Freiherr von Neurath (2 February 1873 – 14 August 1956) was a German diplomat and Nazi war criminal who served as Foreign Minister of Germany between 1932 and 1938.

Born to a Swabian noble family, Neurath began his di ...

and Karl Hermann Frank, which projected the Germanization of the "racially valuable" half of the Czech population after the end of the war. This consisted mainly of industrial workers and farmers. The undesirable half contained the intelligentsia, whom the Nazis viewed as ''ungermanizable'' and potential dangerous instigators of Czech nationalism. Some 9,000 Volksdeutsche

In Nazi German terminology, ''Volksdeutsche'' () were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of '' volksdeutsch'', with ''Volksdeutsche'' denoting a sin ...

from Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter BergerT ...

, Dobruja

Dobruja or Dobrudja (; bg, Добруджа, Dobrudzha or ''Dobrudža''; ro, Dobrogea, or ; tr, Dobruca) is a historical region in the Balkans that has been divided since the 19th century between the territories of Bulgaria and Romania. I ...

, South Tyrol

it, Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano – Alto Adige lld, Provinzia Autonoma de Balsan/Bulsan – Südtirol

, settlement_type = Autonomous province

, image_skyline =

, image_alt ...

, Bessarabia, Sudetenland and the Altreich were settled in the protectorate during the war. The goal was to create a German settlement belt from Prague to Sudetenland, and to turn the surroundings of Olomouc (Olmütz), České Budějovice (Budweis), Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

(Brünn) and the area near the Slovak border into German enclaves.

Further integration of the protectorate into the Reich was carried out by the employment of German apprentices, by transferring German evacuee children into schools located in the protectorate, and by authorizing marriages between Germans and "assimilable" Czechs. Germanizable Czechs were allowed to join the Reich Labour Service

The Reich Labour Service (''Reichsarbeitsdienst''; RAD) was a major organisation established in Nazi Germany as an agency to help mitigate the effects of unemployment on the German economy, militarise the workforce and indoctrinate it with Nazi ...

and to be admitted to German universities.Education

In common with the other "submerged" nations of Eastern Europe, the Czech ''intelligentsia'' had an immense prestige as the bearers and protectors of the national culture, who would keep the Czech language and culture alive when the Czech nation was "submerged". No segment of the Czech ''intelligentsia'' faced more pressure to conform to the occupation policy than school teachers. Frank called the teachers "the most dangerous wing of the ''intelligentsia''" while Heydrich referred to the teachers as "the training core of the opposition Czech governmentn exile in London

N, or n, is the fourteenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''.

History

...

. To keep their jobs, teachers were required to demonstrate fluency in German and were supposed to greet their students with the fascist salute while saying "''Sieg Heil!''" ("Hail Victory!"). School inspectors made surprise visits to the classrooms and all chairpersons of the exam boards had to be ethnic Germans. Some teachers and students were Gestapo informers, which spread a climate of mistrust and paranoia across the school system as both teachers and students never knew whom to trust. One teacher recalled: "The Gestapo even had informers and agents amongst the children. Uncertainty and mistrust destroyed any feeling of comradeship among the children".

Despite these pressures, a number of Czech teachers quietly inserted "anti-''Reich''" ideas into their lessons while refusing to greet their students with "''Sieg Heil!''". Especially under Frank, the teachers suffered harshly. In the first six months of 1944, about 1,000 Czech teachers were either executed or imprisoned. By 1945, about 5,000 Czech teachers were imprisoned in the concentration camps, where a fifth died. By the end of the occupation, about 40% of all Czech teachers had been fired with the figure reaching 60% in Prague.

Administrative subdivisions

Protectorate districts

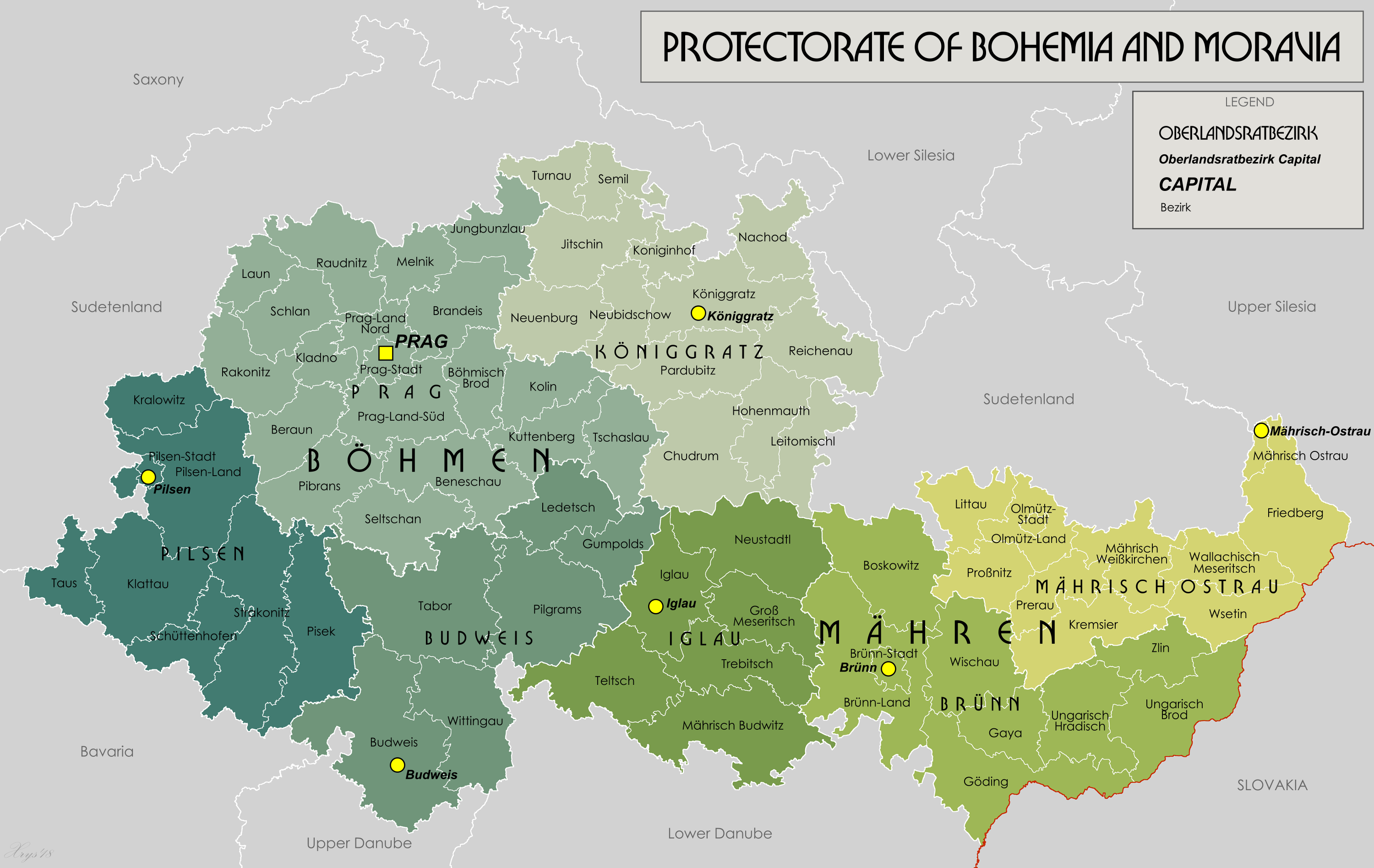

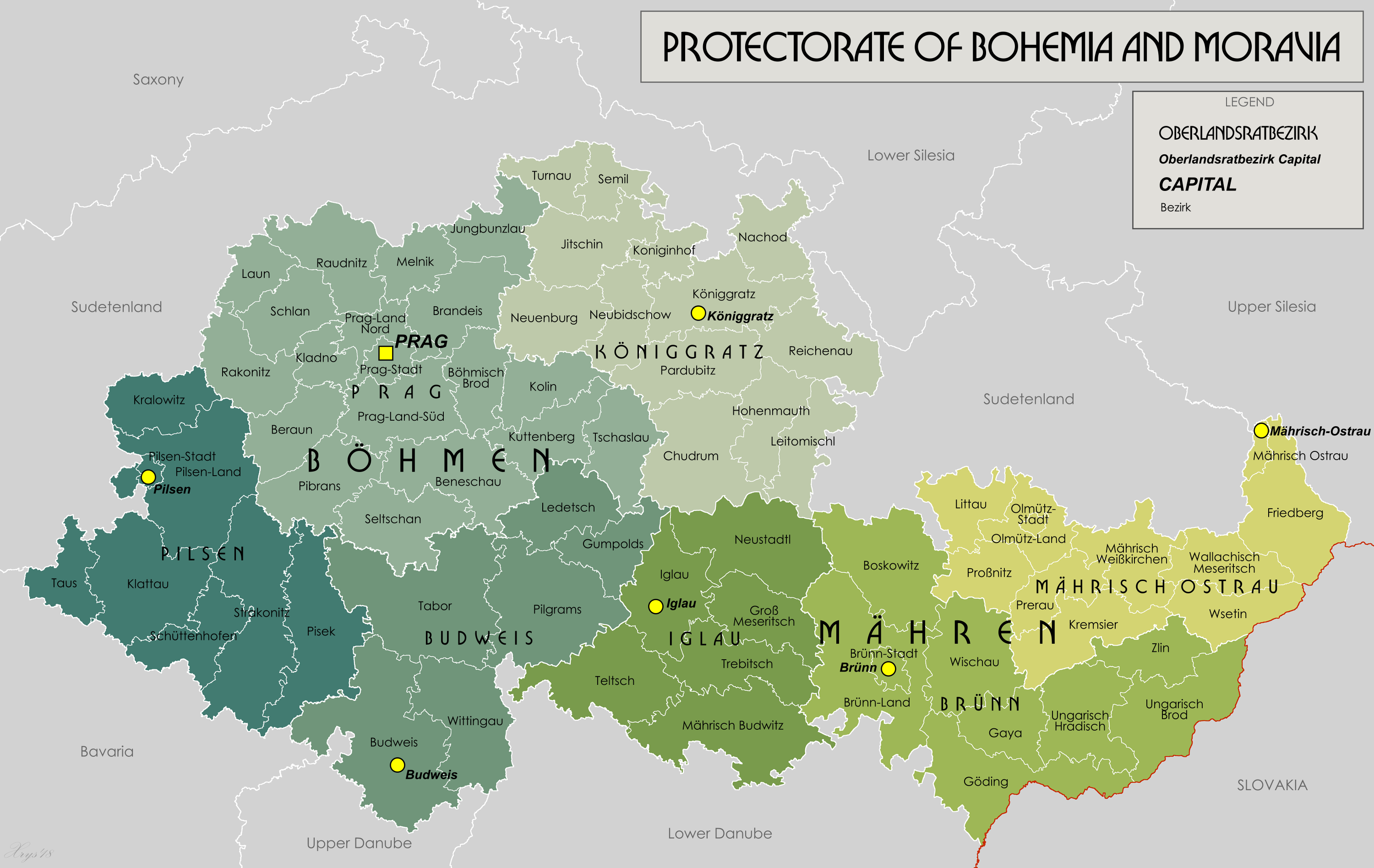

For administrative purposes the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was divided into two Länder: Böhmen (Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

) and Mähren (Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The me ...

). Each of these was further subdivided into ''Oberlandratsbezirke'', each comprising a number of ''Bezirke''.

NSDAP districts

For party administrative purposes theNazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

extended its Gau-system to Bohemia and Moravia when the Protectorate was established. This step divided the remaining parts of Bohemia and Moravia up between its four surrounding ''Gaue'':

* Reichsgau Sudetenland

The Reichsgau Sudetenland was an administrative division of Nazi Germany from 1939 to 1945. It comprised the northern part of the ''Sudetenland'' territory, which was annexed from Czechoslovakia according to the 30 September 1938 Munich Agreement. ...

* Gau Bayreuth

Gau Bayreuth (until June 1942, ''Gau Bayerische Ostmark'' (English: Bavarian Eastern March)) was an administrative division of Nazi Germany formed by the 19 January 1933 merger of Gaue in Lower Bavaria, Upper Palatinate and Upper Franconia, Bavari ...

(Bavarian Eastern March)

* Reichsgau Niederdonau

The Reichsgau Lower Danube (German: ''Reichsgau Niederdonau'') was an administrative division of Nazi Germany consisting of areas in Lower Austria, Burgenland, southeastern parts of Bohemia, southern parts of Moravia, later expanded with Devín an ...

(Lower Danube)

* Reichsgau Oberdonau

The Reichsgau Upper Danube (German: ''Reichsgau Oberdonau'') was an administrative division of Nazi Germany, created after the Anschluss (annexation of Austria) in 1938 and dissolved in 1945. It consisted of what is today Upper Austria, parts of So ...

(Upper Danube)

The resulting government overlap led to the usual authority conflicts typical of the Nazi era. Seeking to extend their own powerbase and to facilitate the area's Germanization the Gauleiter

A ''Gauleiter'' () was a regional leader of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) who served as the head of a ''Administrative divisions of Nazi Germany, Gau'' or ''Reichsgau''. ''Gauleiter'' was the third-highest Ranks and insignia of the Nazi Party, rank in ...

s of the surrounding districts continually agitated for the liquidation of the Protectorate and its direct incorporation into the German Reich. Hitler stated as late as 1943 that the issue was still to be decisively settled.

Military commander

Like in other occupied countries, the German military in Bohemia and Moravia was commanded by a ''Wehrmachtbefehlshaber

The () was the German chief military position, in countries occupied by the Wehrmacht which were headed by a civilian administration. The main objective was military security in the area, and command the defense in case of attack or invasion. Th ...

''. Through the year, the headquarter received several different names because of the complex structure of the ''Reichsprotektorat'': ''Wehrmachtbevollmächtigter beim Reichsprotektor in Böhmen und Mähren'', ''Wehrmachtbefehlshaber beim Reichsprotektor in Böhmen und Mähren'' and ''Wehrmachtbefehlshaber beim deutschen Staatsminister in Böhmen und Mähren''.

The commander also held the position of the ''Befehlshaber im Wehrkreis Böhmen und Mähren''.

Commanders

*''General der Infanterie''Erich Friderici __NOTOC__

Erich Friderici (21 December 1885 – 19 September 1967) was a German general during World War II. He was the commander of Army Group South Rear Area behind Army Group South from 27 October 1941 to 9 January 1942, while the original comman ...

(1 April 1939–27 October 1941)

*''General der Infanterie'' Rudolf Toussaint (1 November 1941–31 August 1943)

*''General der Panzertruppen'' Ferdinand Schaal (1 September 1943–26 July 1944) (arrested after the 20 July plot

On 20 July 1944, Claus von Stauffenberg and other conspirators attempted to assassinate Adolf Hitler, Führer of Nazi Germany, inside his Wolf's Lair field headquarters near Rastenburg, East Prussia, now Kętrzyn, in present-day Poland. The ...

)

*''General der Infanterie'' Rudolf Toussaint (26 July 1944–8 May 1945)

See also

*List of rulers of the Protectorate Bohemia and Moravia

This is a list of rulers of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, which from 15 March 1939 until 5 May 1945 comprised the German- occupied parts of Czechoslovakia. It includes both the representatives of the recognized Czech authorities as w ...

* Government Army

* German occupation of Czechoslovakia

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

* Prague Offensive

The Prague offensive (russian: Пражская стратегическая наступательная операция, Prazhskaya strategicheskaya nastupatel'naya operatsiya, lit=Prague strategic offensive) was the last major military ...

* History of Slovakia

* Concentration camps Lety and Hodonín

Lety concentration camp was a World War II internment camp for Romani people from Bohemia and Moravia during the German occupation of Czechoslovakia. It was located in Lety.

Background

On 2 March 1939 (two weeks before the German occupation) ...

* Out Distance

* Slovak Republic (1939–1945)

References

Informational notes Citations Bibliography * Bryant, Chad. ''Prague in Black: Nazi Rule and Czech Nationalism''. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2009* * * * * Further reading * *

External links

Maps of the Protectorate Bohemia and Moravia

* * ttp://terkepek.adatbank.transindex.ro/kepek/netre/198.gif Hungarian language map with land transfers by Germany, Hungary, and Poland in the late 1930s.

Maps of Europe

showing the breakup of Czechoslovakia and the creation of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia at omniatlas.com

State Secretary in the Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia 1939–1945

German State Ministry of Bohemia and Moravia 1939–1945

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bohemia and Moravia, Protectorate of

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

German military occupations

Bohemia and Moravia

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

.1939

Germanization

Collaboration with the Axis Powers