Prospero Farinacci on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

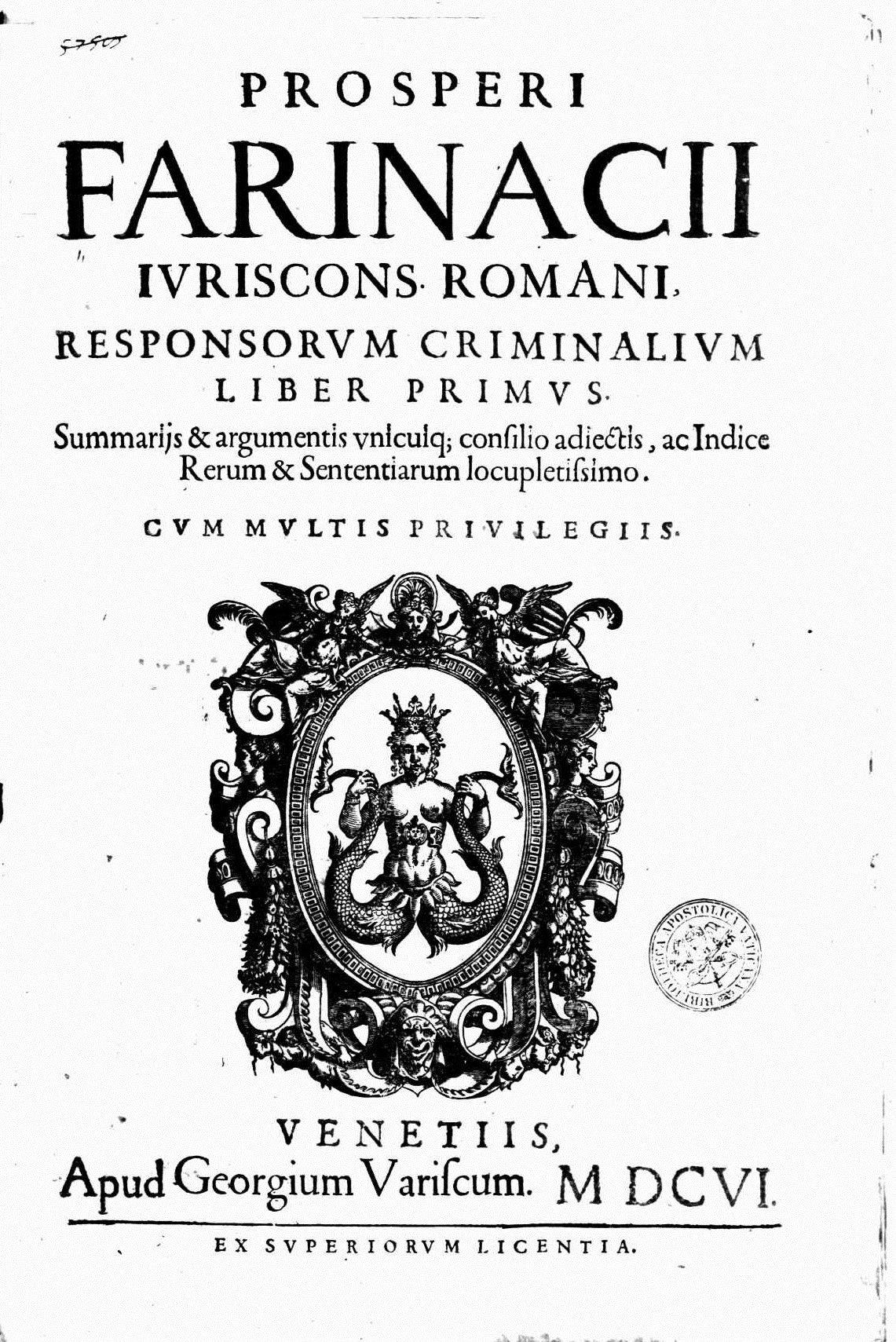

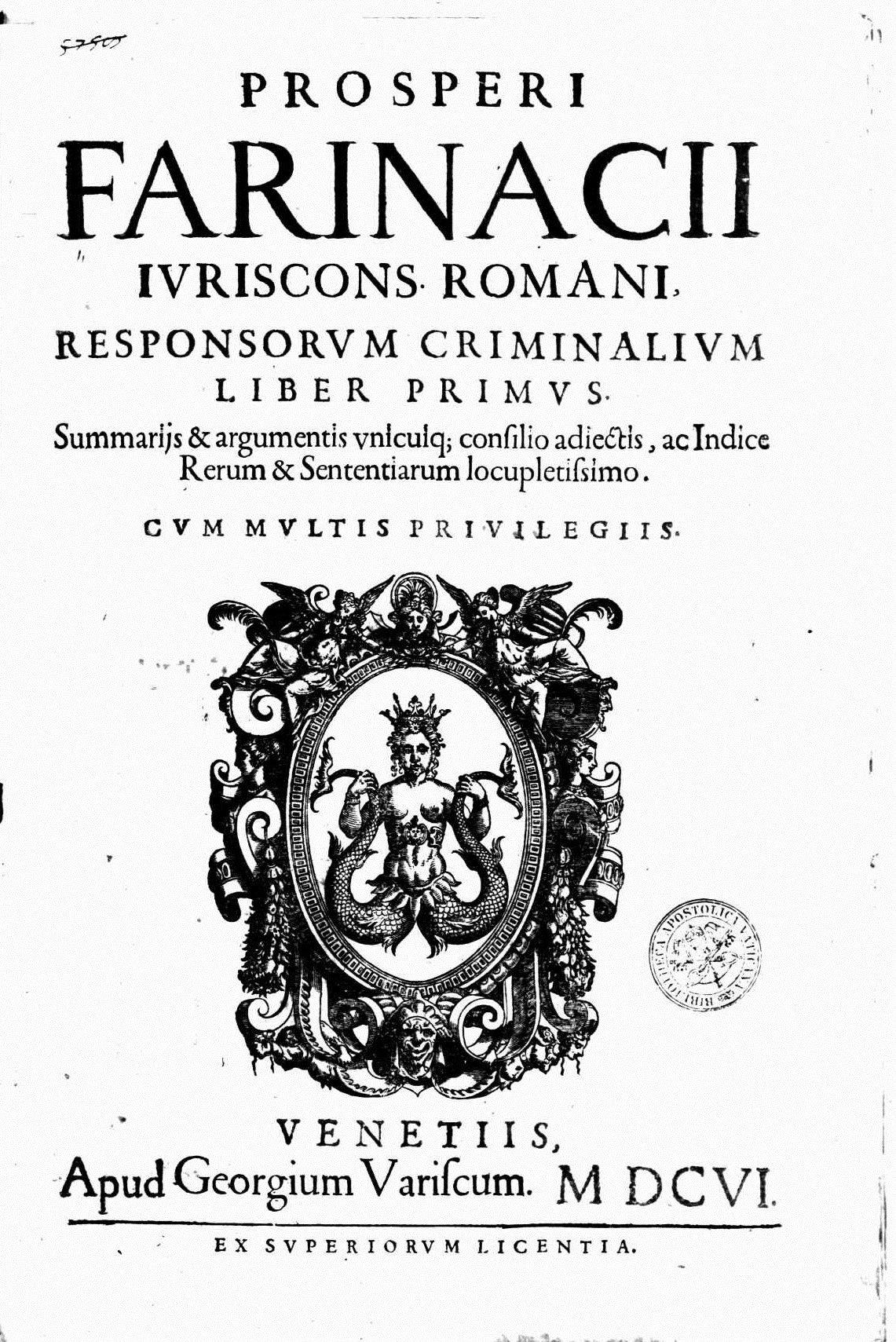

Prospero Farinacci (1 November 1554 – 31 December 1618) was an Italian

Prospero Farinacci was best known for his legal decisions and opinions which he published in four massive tomes and many editions. His most important works are:

*''Praxis et theorica criminalis'', 1594–1614. Farinacci's ''Praxis et Theorica Criminalis'' exerted a very considerable influence on Western legal culture and became a fundamental reference point in Civil law countries in the

Prospero Farinacci was best known for his legal decisions and opinions which he published in four massive tomes and many editions. His most important works are:

*''Praxis et theorica criminalis'', 1594–1614. Farinacci's ''Praxis et Theorica Criminalis'' exerted a very considerable influence on Western legal culture and became a fundamental reference point in Civil law countries in the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

jurist, lawyer and judge. His ''Praxis et Theorica Criminalis'' (Practice and Theory of Criminal Law) was the strongest influence on criminal law

Criminal law is the body of law that relates to crime. It prescribes conduct perceived as threatening, harmful, or otherwise endangering to the property, health, safety, and moral welfare of people inclusive of one's self. Most criminal law i ...

in Civil law countries until the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

. Farinacci defended Beatrice Cenci

Beatrice Cenci (; 6 February 157711 September 1599) was a Roman noblewoman who murdered her father, Count Francesco Cenci. She was beheaded in 1599 after a lurid murder trial in Rome that gave rise to an enduring legend about her.

Life

Beatri ...

who was accused of killing her father in the most famous criminal case of the time. As a judge he was known for his harsh sentencing

In law, a sentence is the punishment for a crime ordered by a trial court after conviction in a criminal procedure, normally at the conclusion of a trial. A sentence may consist of imprisonment, a fine, or other sanctions. Sentences for mult ...

.

Biography

The son of a Capitoline notary, Farinacci was born in Rome in 1554. He studiedlaw

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

at La Sapienza

The Sapienza University of Rome ( it, Sapienza – Università di Roma), also called simply Sapienza or the University of Rome, and formally the Università degli Studi di Roma "La Sapienza", is a public research university located in Rome, Ita ...

in Rome, receiving his doctorate

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''l ...

in 1567 at the early age of twenty-three. Prospero soon earned himself the reputation as an able advocate

An advocate is a professional in the field of law. Different countries' legal systems use the term with somewhat differing meanings. The broad equivalent in many English law–based jurisdictions could be a barrister or a solicitor. However, ...

. In 1567 he became the general commissioner in the service of the Orsini family

The House of Orsini is an Italian noble family that was one of the most influential princely families in medieval Italy and Renaissance Rome. Members of the Orsini family include five popes: Stephen II (752-757), Paul I (757-767), Celestine II ...

of Bracciano

Bracciano is a small town in the Italian region of Lazio, northwest of Rome. The town is famous for its volcanic lake ( Lago di Bracciano or "Sabatino", the eighth largest lake in Italy) and for a particularly well-preserved medieval castle Cast ...

. He reached the height of his professional career as the Papal Datario (the officer of the Roman Curia who investigates candidates for papal benefices) under Pope Clement VIII

Pope Clement VIII ( la, Clemens VIII; it, Clemente VIII; 24 February 1536 – 3 March 1605), born Ippolito Aldobrandini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 February 1592 to his death in March 1605.

Born ...

(1592–1605). He went on to become Giureconsulto e Procuratore Fiscale della Camera Apostolica (Consulting Jurist and Tax Attorney for the papal Treasury) under Pope Paul V

Pope Paul V ( la, Paulus V; it, Paolo V) (17 September 1550 – 28 January 1621), born Camillo Borghese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 16 May 1605 to his death in January 1621. In 1611, he honored ...

.

Along with this eminence, he was also a notoriously difficult character with quite a checkered private life. In 1570 he was imprisoned for an unknown crime. In 1582 he was stabbed in the face in a street fight, leaving him with a diagonal scar

A scar (or scar tissue) is an area of fibrous tissue that replaces normal skin after an injury. Scars result from the biological process of wound repair in the skin, as well as in other organs, and tissues of the body. Thus, scarring is a na ...

on the left cheek and a blind left eye. In 1584 he was jailed for the serious crime of bearing arms in public. Whilst he was a staunch prosecutor of sodomites, in 1595 he was himself accused of sodomy

Sodomy () or buggery (British English) is generally anal or oral sex between people, or sexual activity between a person and a non-human animal ( bestiality), but it may also mean any non- procreative sexual activity. Originally, the term ''sodo ...

with Bernardino Rocchi, a sixteen-year-old page

Page most commonly refers to:

* Page (paper), one side of a leaf of paper, as in a book

Page, PAGE, pages, or paging may also refer to:

Roles

* Page (assistance occupation), a professional occupation

* Page (servant), traditionally a young mal ...

in the Palazzo Altemps

The National Roman Museum (Italian: ''Museo Nazionale Romano'') is a museum, with several branches in separate buildings throughout the city of Rome, Italy. It shows exhibits from the pre- and early history of Rome, with a focus on archaeological ...

, the house of his benefactor.. He was excused of the crime by Pope Clement VIII, who famously made a pun on Farinacci's name (which alludes to "flour" in Italian) by claiming that "The flour is good, it's the bag that's bad."

Farinacci was perhaps most famous as the advocate in the scandalous trial

In law, a trial is a coming together of Party (law), parties to a :wikt:dispute, dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence (law), evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to Adjudication, adjudicate claims or d ...

for murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person wit ...

, actually patricide

Patricide is (i) the act of killing one's own father, or (ii) a person who kills their own father or stepfather. The word ''patricide'' derives from the Greek word ''pater'' (father) and the Latin suffix ''-cida'' (cutter or killer). Patricide ...

, of Beatrice Cenci and her relatives (1599), which ended in their gruesome public beheadings. He played a major role in the defense and although he was not able to save the girl, he did convince the pope to allow the youngest brother, Bernardo, to survive, invoking both the boy's young age and temporary mental infirmity as mitigating factors

In criminal law, a mitigating factor, also known as an extenuating circumstance, is any information or evidence presented to the court regarding the defendant or the circumstances of the crime that might result in reduced charges or a lesser sente ...

.

In 1600 Farinacci had a son with a prostitute

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-penet ...

called Cleria. Ludovico later joined the clergy and in the end became his father’s sole heir. Prospero's portrait by Giuseppe Cesari

Giuseppe Cesari (14 February 1568 – 3 July 1640) was an Italian Mannerist painter, also named Il Giuseppino and called ''Cavaliere d'Arpino'', because he was created ''Cavaliere di Cristo'' by his patron Pope Clement VIII. He was much patronize ...

can be found in the Museo nazionale di Castel Sant'Angelo.

Works

Prospero Farinacci was best known for his legal decisions and opinions which he published in four massive tomes and many editions. His most important works are:

*''Praxis et theorica criminalis'', 1594–1614. Farinacci's ''Praxis et Theorica Criminalis'' exerted a very considerable influence on Western legal culture and became a fundamental reference point in Civil law countries in the

Prospero Farinacci was best known for his legal decisions and opinions which he published in four massive tomes and many editions. His most important works are:

*''Praxis et theorica criminalis'', 1594–1614. Farinacci's ''Praxis et Theorica Criminalis'' exerted a very considerable influence on Western legal culture and became a fundamental reference point in Civil law countries in the modern era

The term modern period or modern era (sometimes also called modern history or modern times) is the period of history that succeeds the Middle Ages (which ended approximately 1500 AD). This terminology is a historical periodization that is applie ...

. The ''Praxis'' was also well known in customary law

A legal custom is the established pattern of behavior that can be objectively verified within a particular social setting. A claim can be carried out in defense of "what has always been done and accepted by law".

Customary law (also, consuetudina ...

countries: Sir George Mackenzie of Rosehaugh

Sir George Mackenzie of Rosehaugh (1636 – May 8, 1691) was a Scottish lawyer, Lord Advocate, essayist and legal writer.

Early life

Mackenzie, who was born in Dundee, was the son of Sir Simon Mackenzie of Lochslin (died c. 1666) and Elizab ...

, writing in Scotland in 1678, drew extensively on Farinacci. The ''Praxis'' is most noteworthy as the definitive work on the jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

of torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons such as punishment, extracting a confession, interrogation for information, or intimidating third parties. Some definitions are restricted to acts c ...

. Farinacci devoted considerable attention to the use of torture in criminal trials and in general placed severe restrictions on its use.

*

*

*

Notes

Further reading

* * * * Graziosi , Marina, 'Women and Criminal Law: the Notion of Diminished Responsibility in Prospero Farinacci and other Renaissance Jurists', in ''Women in Italian Renaissance Culture and Society'', L. Panizza, ed., Oxford (EHRC), 2000, pp. 166–181. * Marchisello, Andrea, “Alieni thori violatio”: l'adulterio come delitto carnale in Prospero Farinacci (1544–1618). In Seidel Menchi, Silvana, and Quaglioni, Diego (eds.), ''Trasgressioni. Seduzione, concubinato, adulterio, bigamia (XIV–XVIII secolo)'', Bologna: il Mulino, 2004, pp. 133–183.External links

* 1554 births 1618 deaths Lawyers from Rome Scholars of criminal law 16th-century Italian jurists 17th-century Italian jurists Writers from Rome Sapienza University of Rome alumni University of Perugia alumni Judges from Rome 17th-century Italian lawyers Italian legal scholars Italian criminologists {{Italy-law-bio-stub