Proclamation Line on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by

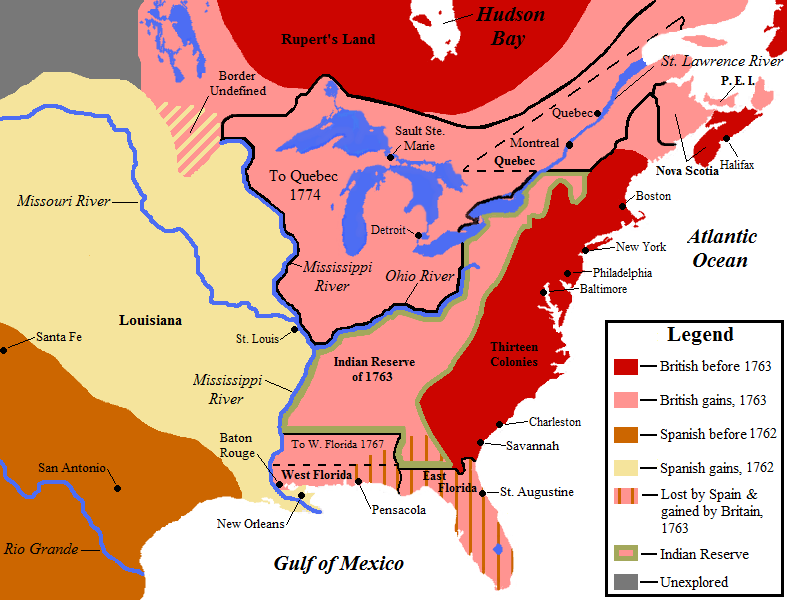

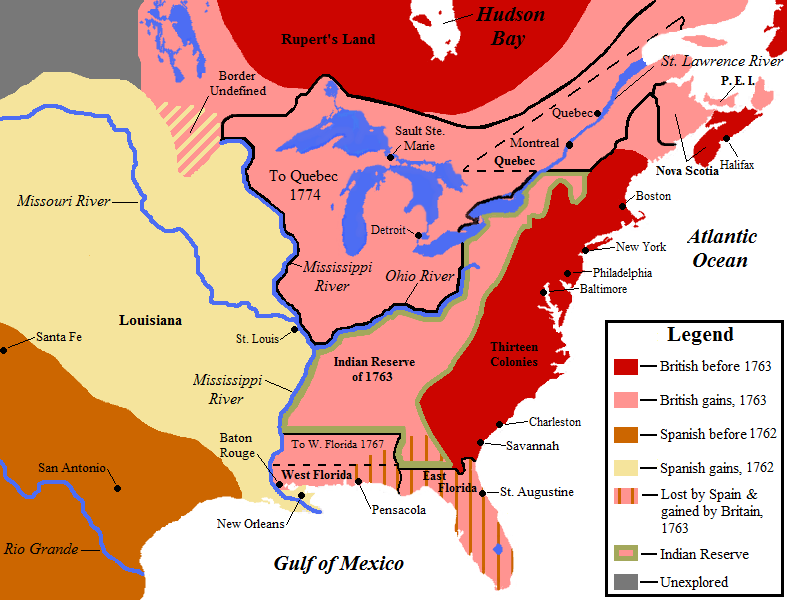

The Proclamation of 1763 dealt with the management of former French territories in North America that Britain acquired following its victory over France in the French and Indian War, as well as regulating colonial settlers' expansion. It established new governments for several areas: the province of Quebec, the new colonies of

The Proclamation of 1763 dealt with the management of former French territories in North America that Britain acquired following its victory over France in the French and Indian War, as well as regulating colonial settlers' expansion. It established new governments for several areas: the province of Quebec, the new colonies of

At the outset, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 defined the jurisdictional limits of the British territories of North America, limiting British colonial expansion on the continent. What remained of the Royal Province of New France east of the

At the outset, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 defined the jurisdictional limits of the British territories of North America, limiting British colonial expansion on the continent. What remained of the Royal Province of New France east of the  British colonists and land speculators objected to the proclamation boundary since the British government had already assigned land grants to them. Including the wealthy owners of the Ohio company who protested the line to the governor of Virginia, as they had plans for settling the land to grow business. Many settlements already existed beyond the proclamation line, some of which had been temporarily evacuated during Pontiac's War, and there were many already granted land claims yet to be settled. For example, George Washington and his Virginia soldiers had been granted lands past the boundary. Prominent American colonials joined with the land speculators in Britain to lobby the government to move the line further west.

The colonists' demands were met and the boundary line was adjusted in a series of treaties with the Native Americans. The first two of these treaties were completed in 1768; the

British colonists and land speculators objected to the proclamation boundary since the British government had already assigned land grants to them. Including the wealthy owners of the Ohio company who protested the line to the governor of Virginia, as they had plans for settling the land to grow business. Many settlements already existed beyond the proclamation line, some of which had been temporarily evacuated during Pontiac's War, and there were many already granted land claims yet to be settled. For example, George Washington and his Virginia soldiers had been granted lands past the boundary. Prominent American colonials joined with the land speculators in Britain to lobby the government to move the line further west.

The colonists' demands were met and the boundary line was adjusted in a series of treaties with the Native Americans. The first two of these treaties were completed in 1768; the

The influence of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 on the coming of the

The influence of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 on the coming of the

''The London Gazette'' of October 4, 1763 Issue: 10354 p. 1

Complete text as published in ''

Complete text of the Royal Proclamation, 1763

Royal Proclamation of 1763

– Chickasaw.TV

Complete text of the Royal Proclamation, 1763

{{DEFAULTSORT:Royal Proclamation Of 1763 1763 in law 1763 in the Thirteen Colonies Aboriginal title in Canada Aboriginal title in the United States Canada–United States relations Colonial United States (British) Constitutions of former British colonies George III of the United Kingdom History of United States expansionism Laws leading to the American Revolution Legal history of Canada Legislation concerning indigenous peoples Monarchy in Canada Pontiac's War Proclamations

King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain, Kingdom of France, France and Spanish Empire, Spain, with Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal in agree ...

, which formally ended the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

and transferred French territory

Overseas France (french: France d'outre-mer) consists of 13 French-administered territories outside Europe, mostly the remains of the French colonial empire that chose to remain a part of the French state under various statuses after decolo ...

in North America to Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

. The Proclamation forbade all settlements west of a line drawn along the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

, which was delineated as an Indian Reserve

In Canada, an Indian reserve (french: réserve indienne) is specified by the '' Indian Act'' as a "tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty,

that has been set apart by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of a band."

Ind ...

. Exclusion from the vast region of Trans-Appalachia

The area in United States west of the Appalachian Mountains and extending vaguely to the Mississippi River, spanning the lower Great Lakes to the upper south, is a region known as trans-Appalachia, particularly when referring to frontier times. It ...

created discontent between Britain and colonial land speculators and potential settlers. The proclamation and access to western lands was one of the first significant areas of dispute between Britain and the colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

and would become a contributing factor leading to the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

. The 1763 proclamation line is situated similar to the Eastern Continental Divide

The Eastern Continental Divide, Eastern Divide or Appalachian Divide is a hydrographic divide in eastern North America that separates the easterly Atlantic Seaboard watershed from the westerly Gulf of Mexico watershed. The divide nearly span ...

, extending from Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

to the divide's northern terminus near the middle of the northern border of Pennsylvania, where it intersects the northeasterly St. Lawrence Divide, and extends further through New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

.

The Royal Proclamation continues to be of legal importance to First Nations

First Nations or first peoples may refer to:

* Indigenous peoples, for ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area.

Indigenous groups

*First Nations is commonly used to describe some Indigenous groups including:

**First Natio ...

in Canada, being the first legal recognition of aboriginal title

Aboriginal title is a common law doctrine that the land rights of indigenous peoples to customary tenure persist after the assumption of sovereignty under settler colonialism. The requirements of proof for the recognition of aboriginal title, ...

, rights and freedoms, and is recognized in the Canadian Constitution

The Constitution of Canada (french: Constitution du Canada) is the supreme law in Canada. It outlines Canada's system of government and the civil and human rights of those who are citizens of Canada and non-citizens in Canada. Its contents a ...

of 1982, in part as a result of direct action by indigenous peoples of Canada, known as the Constitution Express movement of 1981–1982.

Background: Treaty of Paris

TheSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

and its North American theater

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actor, actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The p ...

, the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

, ended with the 1763 Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

. Under the treaty, all French colonial territory west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

was ceded to Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, while all French colonial territory east of the Mississippi River and south of Rupert's Land (save Saint Pierre and Miquelon

Saint Pierre and Miquelon (), officially the Territorial Collectivity of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon (french: link=no, Collectivité territoriale de Saint-Pierre et Miquelon ), is a self-governing territorial overseas collectivity of France in t ...

, which France kept) was ceded to Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

. Both Spain and Britain received some French islands in the Caribbean, while France kept Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

and Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and the ...

.

Provisions

New colonies

The Proclamation of 1763 dealt with the management of former French territories in North America that Britain acquired following its victory over France in the French and Indian War, as well as regulating colonial settlers' expansion. It established new governments for several areas: the province of Quebec, the new colonies of

The Proclamation of 1763 dealt with the management of former French territories in North America that Britain acquired following its victory over France in the French and Indian War, as well as regulating colonial settlers' expansion. It established new governments for several areas: the province of Quebec, the new colonies of West Florida

West Florida ( es, Florida Occidental) was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. As its name suggests, it was formed out of the western part of former S ...

and East Florida

East Florida ( es, Florida Oriental) was a colony of Great Britain from 1763 to 1783 and a province of Spanish Florida from 1783 to 1821. Great Britain gained control of the long-established Spanish colony of ''La Florida'' in 1763 as part of ...

, and a group of Caribbean islands, Grenada

Grenada ( ; Grenadian Creole French: ) is an island country in the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea at the southern end of the Grenadines island chain. Grenada consists of the island of Grenada itself, two smaller islands, Carriacou and Pe ...

, Tobago

Tobago () is an List of islands of Trinidad and Tobago, island and Regions and municipalities of Trinidad and Tobago, ward within the Trinidad and Tobago, Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. It is located northeast of the larger island of Trini ...

, Saint Vincent, and Dominica

Dominica ( or ; Kalinago: ; french: Dominique; Dominican Creole French: ), officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of the island. It is geographically ...

, collectively referred to as the British Ceded Islands.

Proclamation line

At the outset, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 defined the jurisdictional limits of the British territories of North America, limiting British colonial expansion on the continent. What remained of the Royal Province of New France east of the

At the outset, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 defined the jurisdictional limits of the British territories of North America, limiting British colonial expansion on the continent. What remained of the Royal Province of New France east of the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

and the Ottawa River

The Ottawa River (french: Rivière des Outaouais, Algonquin: ''Kichi-Sìbì/Kitchissippi'') is a river in the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec. It is named after the Algonquin word 'to trade', as it was the major trade route of Eastern ...

, and south of Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (french: Terre de Rupert), or Prince Rupert's Land (french: Terre du Prince Rupert, link=no), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin; this was further extended from Rupert's Land t ...

, was reorganised under the name "Quebec." The territory northeast of the St. John River on the Labrador

, nickname = "The Big Land"

, etymology =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 ...

coast was reassigned to the Newfoundland Colony

Newfoundland Colony was an English and, later, British colony established in 1610 on the island of Newfoundland off the Atlantic coast of Canada, in what is now the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. That followed decades of sporadic English ...

. The lands west of Quebec and west of a line running along the crest of the Allegheny Mountains

The Allegheny Mountain Range (; also spelled Alleghany or Allegany), informally the Alleghenies, is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the Eastern United States and Canada and posed a significant barrier to land travel in less devel ...

became (British) Indian Territory, barred to settlement from colonies east of the line.

The proclamation line was not intended to be a permanent boundary between the colonists and Native American lands, but rather a temporary boundary that could be extended further west in an orderly, lawful manner. It was also not designed as an uncrossable boundary; people could cross the line, but not settle past it. Its contour was defined by the headwaters that formed the watershed along the Appalachians. All land with rivers that flowed into the Atlantic was designated for the colonial entities, while all the land with rivers that flowed into the Mississippi was reserved for the Native American populations. The proclamation outlawed the private purchase of Native American land, which had often created problems in the past. Instead, all future land purchases were to be made by Crown officials "at some public Meeting or Assembly of the said Indians". British colonials were forbidden to settle on native lands, and colonial officials were forbidden to grant ground or lands without royal approval. Organized land companies asked for land grants, but were denied by King George III.

British colonists and land speculators objected to the proclamation boundary since the British government had already assigned land grants to them. Including the wealthy owners of the Ohio company who protested the line to the governor of Virginia, as they had plans for settling the land to grow business. Many settlements already existed beyond the proclamation line, some of which had been temporarily evacuated during Pontiac's War, and there were many already granted land claims yet to be settled. For example, George Washington and his Virginia soldiers had been granted lands past the boundary. Prominent American colonials joined with the land speculators in Britain to lobby the government to move the line further west.

The colonists' demands were met and the boundary line was adjusted in a series of treaties with the Native Americans. The first two of these treaties were completed in 1768; the

British colonists and land speculators objected to the proclamation boundary since the British government had already assigned land grants to them. Including the wealthy owners of the Ohio company who protested the line to the governor of Virginia, as they had plans for settling the land to grow business. Many settlements already existed beyond the proclamation line, some of which had been temporarily evacuated during Pontiac's War, and there were many already granted land claims yet to be settled. For example, George Washington and his Virginia soldiers had been granted lands past the boundary. Prominent American colonials joined with the land speculators in Britain to lobby the government to move the line further west.

The colonists' demands were met and the boundary line was adjusted in a series of treaties with the Native Americans. The first two of these treaties were completed in 1768; the Treaty of Fort Stanwix

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix was a treaty signed between representatives from the Iroquois and Great Britain (accompanied by negotiators from New Jersey, Virginia and Pennsylvania) in 1768 at Fort Stanwix. It was negotiated between Sir William J ...

adjusted the border with the Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

in the Ohio Country and the Treaty of Hard Labour

In an effort to resolve concerns of settlers and land speculators following the western boundary established by the Royal Proclamation of 1763 by King George III, it was desired to move the boundary farther west to encompass more settlers who were ...

adjusted the border with the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

in the Carolinas. The Treaty of Hard Labour was followed by the Treaty of Lochaber

The Treaty of Lochaber was signed in South Carolina on 18 October 1770 by British representative John Stuart and the Cherokee people, fixing the boundary for the western limit of the colonial frontier settlements of Virginia and North Carolina.

...

in 1770, adjusting the border between Virginia and the Cherokee. These agreements opened much of what is now Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

and West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

to British settlement. The land granted by the Virginian and North Carolinian government heavily favored the land companies, seeing as they had more wealthy backers than the poorer settlers who wanted to settle west to hopefully gain a fortune.

Response

Many colonists disregarded the proclamation line and settled west, which created tension between them and the Native Americans.Pontiac's Rebellion

Pontiac's War (also known as Pontiac's Conspiracy or Pontiac's Rebellion) was launched in 1763 by a loose confederation of Native Americans dissatisfied with British rule in the Great Lakes region following the French and Indian War (1754–176 ...

(1763–1766) was a war involving Native American tribes, primarily from the Great Lakes region

The Great Lakes region of North America is a binational Canadian–American region that includes portions of the eight U.S. states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin along with the Canadian p ...

, the Illinois Country

The Illinois Country (french: Pays des Illinois ; , i.e. the Illinois people)—sometimes referred to as Upper Louisiana (french: Haute-Louisiane ; es, Alta Luisiana)—was a vast region of New France claimed in the 1600s in what is n ...

, and Ohio Country who were dissatisfied with British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

postwar policies in the Great Lakes region after the end of the Seven Years' War. They were able to take over a large number of the forts which commanded the waterways involved in trade within the region and export to Great Britain. The Proclamation of 1763 had been in the works before Pontiac's Rebellion, but the outbreak of the conflict hastened the process.

Legacy

Indigenous peoples

The Royal Proclamation continued to govern the cession of Indigenous land inBritish North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English overseas possessions, English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland (island), Newfound ...

, especially Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the ...

and Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (french: Terre de Rupert), or Prince Rupert's Land (french: Terre du Prince Rupert, link=no), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin; this was further extended from Rupert's Land t ...

. Upper Canada created a platform for treaty making based on the Royal Proclamation. After loyalists moved into land after Britain's defeat in the American Revolution, the first impetus was created out of necessity.

According to historian Colin Calloway, "scholars disagree on whether the proclamation recognized or undermined tribal sovereignty".

Some see the Royal Proclamation of 1763 as a "fundamental document" for First Nations land claims and self-government

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form of ...

. It is "the first legal recognition by the British Crown

The Crown is the state (polity), state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, British Overseas Territories, overseas territories, Provinces and territorie ...

of Aboriginal rights

Indigenous rights are those rights that exist in recognition of the specific condition of the Indigenous peoples. This includes not only the most basic human rights of physical survival and integrity, but also the Indigenous land rights, rights ...

" and imposes a fiduciary

A fiduciary is a person who holds a legal or ethical relationship of trust with one or more other parties (person or group of persons). Typically, a fiduciary prudently takes care of money or other assets for another person. One party, for exampl ...

duty of care on the Crown. The intent and promises made to the native in the Proclamation have been argued to be of a temporary nature, only meant to appease the Native peoples who were becoming increasingly resentful of "settler encroachments on their lands" and were capable of becoming a serious threat to British colonial settlement. Advice given by a Sir William Johnson

Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet of New York ( – 11 July 1774), was a British Army officer and colonial administrator from Ireland. As a young man, Johnson moved to the Province of New York to manage an estate purchased by his uncle, Royal Na ...

, superintendent of Indian Affairs in North America, to the Board of Trade on August 30, 1764, expressed that:

Anishinaabe jurist John Borrows

John Borrows (or Kegedonce in Anishinaabe) is a Canadian academic and jurist. He is a full professor of law at the University of Victoria Faculty of Law, where he holds the Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Law. He is known as a leading auth ...

has written that "the Proclamation illustrates the British government's attempt to exercise sovereignty over First Nations while simultaneously trying to convince First Nations that they would remain separate from European settlers and have their jurisdiction preserved." Borrows further writes that the Royal Proclamation along with the subsequent Treaty of Niagara

The Treaty of Fort Niagara is one of several treaties signed between the British Crown and various indigenous peoples of North America.

Treaty of Niagara (1764)

The 1764 Treaty of Niagara was agreed to by Sir William Johnson for the Crown and ...

, provide for an argument that "discredits the claims of the Crown to exercise sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

over First Nations" and affirms Aboriginal "powers of self-determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a ''jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It stat ...

in, among other things, allocating lands".

Johnson v Mcintosh

The functional content of the proclamation was reintroduced into American law via Johnson v. Mcintosh823

__NOTOC__

Year 823 ( DCCCXXIII) was a common year starting on Thursday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* Emperor Michael II defeats the rebel forces under Thomas the Sla ...

250th anniversary celebrations

In October 2013, the 250th anniversary of the Royal Proclamation was celebrated inOttawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

with a meeting of Indigenous leaders and Governor-General David Johnston. The Aboriginal movement Idle No More

Idle No More is an ongoing protest Social movement, movement, founded in December 2012 by four women: three First Nations in Canada, First Nations women and one non-Native ally. It is a grassroots movement among the Indigenous peoples in Canad ...

held birthday parties for this monumental document at various locations across Canada.

United States

The influence of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 on the coming of the

The influence of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 on the coming of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

has been variously interpreted. Many historians argue that the proclamation ceased to be a major source of tension after 1768 since the aforementioned later treaties opened up extensive lands for settlement. Others have argued that colonial resentment of the proclamation contributed to the growing divide between the colonies and the mother country. Some historians argue that even though the boundary was pushed west in subsequent treaties, the British government refused to permit new colonial settlements for fear of instigating a war with Native Americans, which angered colonial land speculators. Others argue that the Royal Proclamation imposed a fiduciary duty of care on the Crown.

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

was given of wild land in the Ohio region for his services in the French and Indian War. In 1770, Washington took the lead in securing the rights of him and his old soldiers in the French War, advancing money to pay expenses on behalf of the common cause and using his influence in the proper quarters. In August 1770, it was decided that Washington should personally make a trip to the western region, where he located and surveyed tracts for himself and military comrades. After some dispute, he was eventually granted letters patent for tracts of land there. The lands involved were open to Virginians under terms of the Treaty of Lochaber of 1770, except for the lands located south of Fort Pitt, now known as Pittsburgh.

In the United States, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 ended with the American Revolutionary War because Great Britain ceded the land in question to the United States in the Treaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed in Paris by representatives of George III, King George III of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and representatives of the United States, United States of America on September 3, 1783, officially ended the Ame ...

. Afterward, the U.S. government also faced difficulties in preventing frontier violence and eventually adopted policies similar to those of the Royal Proclamation. The first in a series of Indian Intercourse Act

The Nonintercourse Act (also known as the Indian Intercourse Act or the Indian Nonintercourse Act) is the collective name given to six statutes passed by the Congress in 1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834 to set Amerindian boundaries of re ...

s was passed in 1790, prohibiting unregulated trade and travel in Native American lands. In 1823, the U.S. Supreme Court case ''Johnson v. M'Intosh

''Johnson v. M'Intosh'', 21 U.S. (7 Wheat.) 543 (1823), is a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court that held that private citizens could not purchase lands from Native Americans. As the facts were recited by Chief Justice John Marshall, t ...

'' established that only the U.S. government, and not private individuals, could purchase land from Native Americans.

See also

*Indian removal

Indian removal was the United States government policy of forced displacement of self-governing tribes of Native Americans from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi Riverspecifically, to a de ...

* Indian barrier state

The Indian barrier state or buffer state was a British proposal to establish a Native American state in the portion of the Great Lakes region of North America. It was never created. The idea was to create it west of the Appalachian Mountains, b ...

* Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

* Indian Reserve (1763)

"Indian Reserve" is a historical term for the largely uncolonized land in North America that was claimed by France, ceded to Great Britain through the Treaty of Paris (1763) at the end of the Seven Years' War—also known as the French and Indian ...

* Halifax Treaties

The Peace and Friendship Treaties were a series of written documents (or, treaties) that Britain signed between 1725 and 1779 with various Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), Abenaki, Penobscot, and Passamaquoddy peoples (i.e., the Wabanaki Confe ...

* Territorial evolution of the Caribbean

Citations

General sources

* * Also * *Further reading

* * * * * The standard scholarly history of the proclamation and its effects. *Canada

* * * * * *External links

''The London Gazette'' of October 4, 1763 Issue: 10354 p. 1

Complete text as published in ''

The London Gazette

''The London Gazette'' is one of the official journals of record or government gazettes of the Government of the United Kingdom, and the most important among such official journals in the United Kingdom, in which certain statutory notices are ...

''

Complete text of the Royal Proclamation, 1763

Royal Proclamation of 1763

– Chickasaw.TV

Complete text of the Royal Proclamation, 1763

{{DEFAULTSORT:Royal Proclamation Of 1763 1763 in law 1763 in the Thirteen Colonies Aboriginal title in Canada Aboriginal title in the United States Canada–United States relations Colonial United States (British) Constitutions of former British colonies George III of the United Kingdom History of United States expansionism Laws leading to the American Revolution Legal history of Canada Legislation concerning indigenous peoples Monarchy in Canada Pontiac's War Proclamations