Prize (law) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In admiralty law prizes are

In admiralty law prizes are

In his book ''The Prize Game'', Donald Petrie writes, "at the outset, prize taking was all smash and grab, like breaking a jeweler's window, but by the fifteenth century a body of guiding rules, the maritime law of nations, had begun to evolve and achieve international recognition."

In his book ''The Prize Game'', Donald Petrie writes, "at the outset, prize taking was all smash and grab, like breaking a jeweler's window, but by the fifteenth century a body of guiding rules, the maritime law of nations, had begun to evolve and achieve international recognition."  With so much at stake, prize law attracted some of the greatest legal talent of the age, including

With so much at stake, prize law attracted some of the greatest legal talent of the age, including

When a privateer or naval vessel spotted a tempting vessel—whatever flag she flew or often enough flying none at all—they gave chase. Sailing under false colors was a common ruse, both for predator and prey. The convention was that a vessel must hoist her true colors before firing the first shot. Firing under a false flag could cost dearly in prize court proceedings, possibly even resulting in restitution to the captured vessel's owner.

Often a single cannon shot across the bow was enough to persuade the prey to

When a privateer or naval vessel spotted a tempting vessel—whatever flag she flew or often enough flying none at all—they gave chase. Sailing under false colors was a common ruse, both for predator and prey. The convention was that a vessel must hoist her true colors before firing the first shot. Firing under a false flag could cost dearly in prize court proceedings, possibly even resulting in restitution to the captured vessel's owner.

Often a single cannon shot across the bow was enough to persuade the prey to

Most privateering came to an end in the late-19th century, when the

Most privateering came to an end in the late-19th century, when the

summary of US Prize laws 1868

{{Authority control Law of the sea Prize warfare

In admiralty law prizes are

In admiralty law prizes are equipment

Equipment most commonly refers to a set of tool

A tool is an object that can extend an individual's ability to modify features of the surrounding environment or help them accomplish a particular task. Although many animals use simple tools, onl ...

, vehicle

A vehicle (from la, vehiculum) is a machine that transports people or cargo. Vehicles include wagons, bicycles, motor vehicles (motorcycles, cars, trucks, buses, mobility scooters for disabled people), railed vehicles (trains, trams), ...

s, vessels, and cargo

Cargo consists of bulk goods conveyed by water, air, or land. In economics, freight is cargo that is transported at a freight rate for commercial gain. ''Cargo'' was originally a shipload but now covers all types of freight, including trans ...

captured during armed conflict. The most common use of ''prize'' in this sense is the capture of an enemy ship

A ship is a large watercraft that travels the world's oceans and other sufficiently deep waterways, carrying cargo or passengers, or in support of specialized missions, such as defense, research, and fishing. Ships are generally distinguished ...

and her cargo

Cargo consists of bulk goods conveyed by water, air, or land. In economics, freight is cargo that is transported at a freight rate for commercial gain. ''Cargo'' was originally a shipload but now covers all types of freight, including trans ...

as a prize of war

A prize of war is a piece of enemy property or land seized by a belligerent party during or after a war or battle, typically at sea. This term was used nearly exclusively in terms of captured ships during the 18th and 19th centuries. Basis in inte ...

. In the past, the capturing force would commonly be allotted a share of the worth of the captured prize. Nations often granted letters of marque that would entitle private parties to capture enemy property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

, usually ships. Once the ship was secured on friendly territory, she would be made the subject of a prize case: an ''in rem

''In rem'' jurisdiction ("power about or against 'the thing) is a legal term describing the power a court may exercise over property (either real or personal) or a "status" against a person over whom the court does not have ''in personam'' jurisd ...

'' proceeding in which the court determined the status of the condemned property and the manner in which the property was to be disposed of.

History and sources of prize law

In his book ''The Prize Game'', Donald Petrie writes, "at the outset, prize taking was all smash and grab, like breaking a jeweler's window, but by the fifteenth century a body of guiding rules, the maritime law of nations, had begun to evolve and achieve international recognition."

In his book ''The Prize Game'', Donald Petrie writes, "at the outset, prize taking was all smash and grab, like breaking a jeweler's window, but by the fifteenth century a body of guiding rules, the maritime law of nations, had begun to evolve and achieve international recognition." Grotius

Hugo Grotius (; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Huig de Groot () and Hugo de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, poet and playwright.

A teenage intellectual prodigy, he was born in Delft ...

's seminal treatise on international law called ''De Iure Praedae Commentarius (Commentary on the Law of Prize and Booty)'', published in 1604—of which Chapter 12, "''Mare Liberum''" inter alia founded the doctrine of freedom of the seas—was an advocate's brief justifying Dutch seizures of Spanish and Portuguese shipping. Grotius defends the practice of taking prizes as not merely traditional or customary, but just. His ''Commentary'' points out that the etymology of the name of the Greek war god Ares was the verb "to seize", and that the law of nations had deemed looting enemy property legal since the beginning of Western recorded history in Homeric times.

Prize law fully developed between the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

of 1756–1763 and the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

of 1861–1865. This period largely coincides with the last century of fighting sail and includes the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, the American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

and French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

s, and America's Quasi-War

The Quasi-War (french: Quasi-guerre) was an undeclared naval war fought from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States. The ability of Congress ...

with France of the late 1790s. Much of Anglo-American prize law derives from 18th Century British precedents – in particular, a compilation called the ''1753 Report of the Law Officers'', authored by William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield

William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, PC, SL (2 March 170520 March 1793) was a British barrister, politician and judge noted for his reform of English law. Born to Scottish nobility, he was educated in Perth, Scotland, before moving to Lond ...

(1705–1793). It was said to be the most important exposition of prize law published in English, along with the subsequent High Court of Admiralty decisions of William Scott, Lord Stowell

William Scott, 1st Baron Stowell (17 October 174528 January 1836) was an English judge and jurist. He served as Judge of the High Court of Admiralty from 1798 to 1828.

Background and education

Scott was born at Heworth, a village about four m ...

(1743–1836).

American Justice Joseph Story

Joseph Story (September 18, 1779 – September 10, 1845) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, serving from 1812 to 1845. He is most remembered for his opinions in ''Martin v. Hunter's Lessee'' and '' United States ...

, the leading United States judicial authority on prize law, drew heavily on the 1753 report and Lord Stowell's decisions, as did Francis Upton, who wrote the last major American treatise on prize law, his ''Maritime Warfare and Prize''.

While the Anglo-American common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omnipresen ...

case precedents are the most accessible description of prize law, in prize cases, courts construe and apply international customs and usages, the Law of Nations

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

, and not the laws or precedents of any one country.

Fortunes in prize money were to be made at sea as vividly depicted in the novels of C. S. Forester and Patrick O'Brian

Patrick O'Brian, CBE (12 December 1914 – 2 January 2000), born Richard Patrick Russ, was an English novelist and translator, best known for his Aubrey–Maturin series of sea novels set in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars, and cent ...

. During the American Revolution the combined American naval and privateering prizes totaled nearly $24 million; in the War of 1812, $45 million. Such huge revenues were earned when $200 were a generous year's wages for a sailor; his share of a single prize could fetch ten or twenty times his yearly pay, and taking five or six prizes in one voyage was common.

With so much at stake, prize law attracted some of the greatest legal talent of the age, including

With so much at stake, prize law attracted some of the greatest legal talent of the age, including John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

, Joseph Story

Joseph Story (September 18, 1779 – September 10, 1845) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, serving from 1812 to 1845. He is most remembered for his opinions in ''Martin v. Hunter's Lessee'' and '' United States ...

, Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison, ...

, and Richard Henry Dana, Jr. author of ''Two Years Before the Mast

''Two Years Before the Mast'' is a memoir by the American author Richard Henry Dana Jr., published in 1840, having been written after a two-year sea voyage from Boston to California on a merchant ship starting in 1834. A film adaptation under the ...

''. Prize cases were among the most complex of the time, as the disposition of vast sums turned on the fluid Law of Nations

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

, and difficult questions of jurisdiction and precedent.

One of the earliest U.S. cases for instance, that of the ''Active'', took fully 30 years to resolve jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' + 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, areas of jurisdiction apply to local, state, and federal levels.

Jur ...

al disputes between state and federal authorities. A captured American privateer captain, 20-year-old Gideon Olmsted, shipped aboard the British sloop ''Active'' in Jamaica as an ordinary hand in an effort to get home. Olmsted organized a mutiny and commandeered the sloop. But as Olmsted's mutineers sailed their prize to America, a Pennsylvania privateer took the ''Active''. Olmsted and the privateer disputed ownership of the prize, and in November 1778 a Philadelphia prize court jury came to a split verdict awarding each a share. Olmsted, with the assistance of then American General Benedict Arnold, appealed to the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

Prize Committee, which reversed the Philadelphia jury verdict and awarded the whole prize to Olmsted. But Pennsylvania authorities refused to enforce the decision, asserting the Continental Congress could not intrude on a state prize court jury verdict. Olmsted doggedly pursued the case for decades until he won, in a U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

case in 1809 which Justice Stanley Matthews later called "the first case in which the supremacy of the Constitution was enforced by judicial tribunals against the assertion of state authority".

Commission

Although Letters of Marque and Reprisal were sometimes issued before a formal declaration of war, as happened during the American Revolution when the rebelling colonies of Massachusetts, Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania all granted Letters of Marque months before the Continental Congress's officialDeclaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

of July 1776, by the turn of the 19th century it was generally accepted that a sovereign government first had to declare war. The "existence of war between nations terminates all legal commercial intercourse between their citizens or subjects," wrote Francis Upton in ''Maritime Warfare and Prize'', since " ade and commerce presuppose the existence of civil contracts … and recourse to judicial tribunals; and this is necessarily incompatible with a state of war." Indeed, each citizen of a nation "is at war with every citizen of the enemy," which imposes a "duty, on every citizen, to attack the enemy and seize his property, though by established custom, this right is restricted to such only, as are the commissioned instruments of the government."

The formal commission bestowed upon a naval vessel, and the Letter of Marque and Reprisal granted to private merchant vessels converting them into naval auxiliaries, qualified them to take enemy property as the armed hands of their sovereign, and to share in the proceeds.

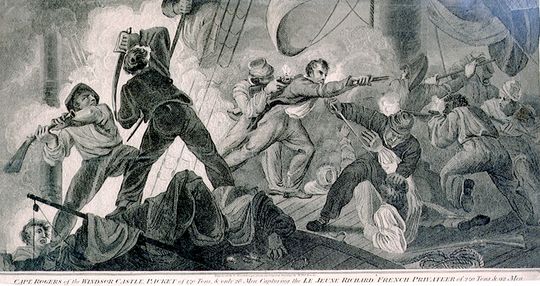

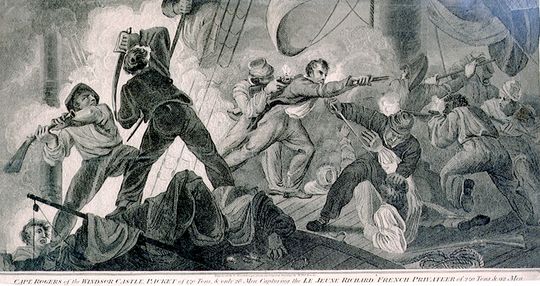

Capturing a prize

When a privateer or naval vessel spotted a tempting vessel—whatever flag she flew or often enough flying none at all—they gave chase. Sailing under false colors was a common ruse, both for predator and prey. The convention was that a vessel must hoist her true colors before firing the first shot. Firing under a false flag could cost dearly in prize court proceedings, possibly even resulting in restitution to the captured vessel's owner.

Often a single cannon shot across the bow was enough to persuade the prey to

When a privateer or naval vessel spotted a tempting vessel—whatever flag she flew or often enough flying none at all—they gave chase. Sailing under false colors was a common ruse, both for predator and prey. The convention was that a vessel must hoist her true colors before firing the first shot. Firing under a false flag could cost dearly in prize court proceedings, possibly even resulting in restitution to the captured vessel's owner.

Often a single cannon shot across the bow was enough to persuade the prey to heave-to

In sailing, heaving to (to heave to and to be hove to) is a way of slowing a sailing vessel's forward progress, as well as fixing the helm and sail positions so that the vessel does not have to be steered. It is commonly used for a "break"; this ...

, but sometimes brutal hours and even days of cannonading ensued, along with boarding and hand-to-hand fighting with cutlasses, pistols, and boarding pikes. No matter how furious and bloody the battle, once it was over the victors had to collect themselves, put aside anger and exercise forbearance, treating captives with courtesy and civility to the degree prudence allowed. Officers restrained the crew to prevent pillaging defeated adversaries, or pilfering the cargo, known as breaking bulk. Francis Upton's treatise on ''Maritime Warfare'' cautioned:

Embezzlements of the cargo seized, or acts personally violent, or injuries perpetrated upon the captured crew, or improperly separating them from the prize-vessel, or not producing them for examination before the prize-court, or other torts injurious to the rights and health of the prisoners, may render the arrest of the vessel or cargo, as prize, defeasible, and also subject the tort feasor for damages therefore.Taking the prize before a prize court might be impractical for any number of reasons, such as bad weather, shortage of prize crew, dwindling water and provisions, or the proximity of an overpowering enemy force—in which case a vessel might be ransomed. That is, instead of destroying her on the spot as was their prerogative, the privateer or naval officer would accept a

scrip

A scrip (or ''chit'' in India) is any substitute for legal tender. It is often a form of credit. Scrips have been created and used for a variety of reasons, including exploitive payment of employees under truck systems; or for use in local co ...

in form of an IOU for an agreed sum as ransom from the ship's master. On land this would be extortion

Extortion is the practice of obtaining benefit through coercion. In most jurisdictions it is likely to constitute a criminal offence; the bulk of this article deals with such cases. Robbery is the simplest and most common form of extortion, ...

and the promise to pay unenforceable in court, but at sea it was accepted practice and the IOUs negotiable instruments.

On occasion a seized vessel would be released to ferry home prisoners, a practice which Lord Stowell said "in the consideration of humanity and policy" Admiralty Courts must protect with the utmost attention. While on her mission as a cartel ship

Cartel ships, in international law, are ships employed on humanitarian voyages, in particular, to carry communications or prisoners between belligerents. They fly distinctive flags, including a flag of truce. Traditionally, they were unarmed but ...

she was immune to recapture so long as she proceeded directly on her errand, promptly returned, and did not engage in trading in the meantime.

Usually, however, the captor put aboard a prize crew to sail a captured vessel to the nearest port of their own or an allied country, where a prize court could adjudicate the prize. If while sailing en route a friendly vessel re-captured the prize, called a rescue, the right of ''postliminium

The principle of postliminium, as a part of public international law, is a specific version of the maxim '' ex injuria jus non oritur'', providing for the invalidity of all illegitimate acts that an occupant may have performed on a given territory ...

'' declared title to the rescued prize restored to its prior owners. That is, the ship did not become a prize of the recapturing vessel. However, the rescuers were entitled to compensation for salvage, just as if they had rescued a crippled vessel from sinking at sea.

Admiralty court process

The prize that made it back to the capturing vessel's country or that of an ally which had authorized prize proceedings would be sued in admiralty court ''in rem''—meaning "against the thing", against the vessel itself. For this reason. decisions in prize cases bear the name of the vessel, such as ''The Rapid'' (a U.S. Supreme Court case holding goods bought before hostilities commenced nonetheless become contraband after war is declared) or ''The Elsebe'' (Lord Stowell holding thatprize court

A prize court is a court (or even a single individual, such as an ambassador or consul) authorized to consider whether prizes have been lawfully captured, typically whether a ship has been lawfully captured or seized in time of war or under the t ...

s enforce rights under the Law of Nations

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

rather than merely the law of their home country). A proper prize court condemnation was absolutely requisite to convey clear title to a vessel and its cargo to the new owners and settle the matter. According to Upton's treatise, "Even after four years' possession, and the performance of several voyages, the title to the property is not changed without sentence of condemnation".

The agent of the privateer or naval officer brought a libel, accusing the captured vessel of belonging to the enemy, or carrying enemy cargo, or running a blockade. Prize commissioners took custody of the vessel and its cargo, and gathered the ship's papers, charts, and other documents. They had a special duty to notify the prize court of perishable property, to be sold promptly to prevent spoilage and the proceeds held for whoever prevailed in the prize proceeding.

The commissioners took testimony from witnesses on standard form written interrogatories

In law, interrogatories (also known as requests for further information) are a formal set of written questions propounded by one litigant and required to be answered by an adversary in order to clarify matters of fact and help to determine in adv ...

. Admiralty courts rarely heard live testimony. The commissioners' interrogatories sought to establish the relative size, speed, and force of the vessels, what signals were exchanged and what fighting ensued, the location of the capture, the state of the weather and "the degree of light or darkness," and what other vessels were in sight. That was because naval prize law gave assisting vessels, defined as those that were "in signal distance" at the time, a share of the proceeds. The written interrogatories and ship's papers established the nationality of the prize and her crew, and the origin and destination of the cargo: the vessel was said to be "confiscated out of her own mouth."

One considerable difference between prize law and ordinary Anglo-American criminal law is the reversal of the normal ''onus probandi'' or burden of proof. While in criminal courts a defendant is innocent until proven guilty, in prize court a vessel is guilty unless proven innocent. Prize captors need show only "reasonable suspicion" that the property is subject to condemnation; the owner bears the burden of proving the contrary.

A prize court normally ordered the vessel and its cargo condemned and sold at auction. But the court's decision became vastly more complicated in the case of neutral vessels, or a neutral nation's cargo carried on an enemy vessel. Different countries treated these situations differently. By the close of the 18th century, Russia, Scandinavia, France, and the United States had taken the position that "free ships make free goods": that is, cargo on a neutral ship could not be condemned as a prize. But Britain asserted the opposite, that an enemy's goods on a neutral vessel, or neutral goods on an enemy vessel, may be taken, a position which prevailed in 19th century practice. The ingenuity of belligerents in evading the law through pretended neutrality, false papers, quick title transfers, and a myriad of other devices, make up the principal business of the prize courts during the last century of fighting sail.

Neutral vessels could be subject to capture if they ran a blockade. The blockade had to be effective to be cognizable in a prize court, that is, not merely declared but actually enforced. Neutrals had to be warned of it. If so then any ships running the blockade of whatever flag were subject to capture and condemnation. However passengers and crew aboard the blockade runners were not to be treated as prisoners of war, as Upton's ''Maritime Warfare and Prize'' enjoins: "the penalty, and the sole penalty ... is the forfeiture of the property employed in lockade running" Persons aboard blockade runners could only be temporarily detained as witnesses, and after testifying, immediately released.

The legitimacy of an adjudication depended on regular and just proceedings. Departures from internationally accepted standards of fairness risked ongoing litigation by disgruntled shipowners and their insurers, often protracted for decades.

For example, during America's Quasi-War

The Quasi-War (french: Quasi-guerre) was an undeclared naval war fought from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States. The ability of Congress ...

with France in the 1790s, corrupt French Caribbean prize courts (often sharing in the proceeds) resorted to pretexts and subterfuges to justify condemning neutral American vessels. They condemned one for carrying alleged English contraband because the compass in the binnacle showed an English brand; another because the pots and pans in the galley were of English manufacture. Outraged U.S. shipowners, their descendants, and descendants of their descendants (often serving as fronts for insurers) challenged these decisions in litigation collectively called the French Spoliation Cases. The spoliation cases last over a century, from the 1790s until 1915. Together with Indian tribal claims for treaty breaches, the French Spoliation Cases enjoy the dubious distinction of figuring among the longest-litigated claims in U.S. history.

Paris Declaration Respecting Maritime Law (1856)

Most privateering came to an end in the late-19th century, when the

Most privateering came to an end in the late-19th century, when the plenipotentiaries

A ''plenipotentiary'' (from the Latin ''plenus'' "full" and ''potens'' "powerful") is a diplomat who has full powers—authorization to sign a treaty or convention on behalf of his or her sovereign. When used as a noun more generally, the word ' ...

who agreed on the Treaty of Paris in March 1856 that did put an end to the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

, also did agree on the Paris Declaration Respecting Maritime Law

The Paris Declaration respecting Maritime Law of 16 April 1856 was an international multilateral treaty agreed to by the warring parties in the Crimean War gathered at the Congress at Paris after the peace treaty of Paris had been signed in March ...

renouncing granting letters of marque. Proposal to the Declaration came from the French Foreign Minister and president of the Congress Count Walewski.

In the plain wordings of the Declaration:

* Privateering is and remains abolished; * The neutral flag covers enemy's goods, with the exception of contraband of war; * Neutral goods, with the exception of contraband of war, are not liable to capture under enemy's flag; * Blockades, in order to be binding, must be effective-that is to say, maintained by a forge sufficient really to prevent access to the coast of the enemy.The Declaration did contain a juridical novelty, making it possible for the first time in history that nations not represented at the establishment and/or the signing of a multilateral treaty, could access as a party afterwards. Again in the plain wordings of the treaty:

"The present Declaration is not and shall not be binding, except between those Powers who have acceded, or shall accede, to it."The declaration has been written in French, translated in English and the two versions have been sent to nations worldwide with the invitation to access, leading to the acceding of altogether 55 nations, a big step towards the globalisation of international law. This broad acceptance wouldn't otherwise haven't been possible in such a short period. The United States however, were not a signatory and had reasons not to accede the treaty afterwards. After having received the invitation to accede, the US Secretary of State, William L. Marcy a lawyer and judge, wrote a letter dated 14 juli 1856 to other nations, among which

The Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

:

"The United States have learned with sincere regret that in one or two instances, the four propositions, with all the conditions annexed, have been promptly, and this Government cannot but think, unadvisedly accepted without restriction or qualification."The US didn't want to restrict privateering and did strive for protection of all private property on neutral of enemy ships. Marcy did warn countries with large commercial maritime interests and a small navy, like The Netherlands, to be aware that the end of privateering meant they would be totally dependent on nations with a strong navy. Marcy did end the letter hoping:

“(…) that it may be induced to hesitate in acceding to a proposition which is here conceived to be fraught with injurious consequences to all but those Powers which already have or are willing to furnish themselves with powerful navies.”The US did accept the other points of the Declaration, being a codification of custom law.

End of privateering and the decline of naval prizes

During theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, Confederate privateer

The Confederate privateers were privately owned ships that were authorized by the government of the Confederate States of America to attack the shipping of the United States. Although the appeal was to profit by capturing merchant vessels and seizi ...

s cruised against Union merchant shipping. Likewise, the Union (though refusing to recognize the legitimacy of Confederate letters of marque) allowed its navy to take Confederate vessels as prizes. Under US Constitution Article 1 Section 8, it is still theoretically possible for Congress to authorize letters of marque, but in the last 150 years it has not done so.

An International Prize Court The International Prize Court was an international court proposed at the beginning of the 20th century, to hear prize cases. An international agreement to create it, the ''Convention Relative to the Creation of an International Prize Court'', was ma ...

was to be set up by treaty XII of the Hague Convention of 1907

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international treaties and declarations negotiated at two international peace conferences at The Hague in the Netherlands. Along with the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions were amo ...

, but this treaty never came into force as only Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

ratified it.

Commerce raiding by private vessels ended with the American Civil War, but Navy officers remained eligible for prize money a little while longer. The United States continued paying prizes to naval officers in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

, and only abjured the practice by statute during World War I. The U.S. prize courts adjudicated no cases resulting from its own takings in either World War I or World War II (although the Supreme Court did rule on a German prize— SS ''Appam'' in the case '' The Steamship Appam''—that was brought to and held at Hampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's ...

). Likewise Russia, Portugal, Germany, Japan, China, Romania, and France followed the United States in World War I, declaring they would no longer pay prize money to naval officers. On November 9, 1914, the British and French governments signed an agreement establishing government jurisdiction over prizes captured by either of them. The Russian government acceded to this agreement on March 5, 1915, and the Italian government followed suit on January 15, 1917.

Shortly before World War II France passed a law which allowed for taking prizes, as did the Netherlands and Norway, though the German invasion and subsequent capitulation of all three of those countries quickly put this to an end. Britain formally ended the eligibility of naval officers to share in prize money in 1948.

Under contemporary international law and treaties, nations may still bring enemy vessels before their prize courts, to be condemned and sold. But no nation now offers a share to the officers or crew who risked their lives in the capture:

Self-interest was the driving force that compelled men of the sea to accept the international law of prize ... ncluding merchantsbecause it brought a valuable element of certainty to their dealings. If the rules were clear and universal, they could ship their goods abroad in wartime, after first buying insurance against known risks. ... On the other side of the table, those purchasing vessels and cargoes from prize courts had the comfort of knowing that what they bought was really theirs. The doctrine and practice of maritime prize was widely adhered to for four centuries, among a multitude of sovereign nations, because adhering to it was in the material interest of their navies, their privateersmen, their merchants and bankers, and their sovereigns. Diplomats and international lawyers who struggle in this world to achieve a universal rule of law may well ponder on this lesson.Petrie, ''The Prize Game'', pp. 145–46.

See also

* ''Alabama'' Claims *Commerce raiding

Commerce raiding (french: guerre de course, "war of the chase"; german: Handelskrieg, "trade war") is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than en ...

*Confederate privateer

The Confederate privateers were privately owned ships that were authorized by the government of the Confederate States of America to attack the shipping of the United States. Although the appeal was to profit by capturing merchant vessels and seizi ...

*Court of Appeals in Cases of Capture

A court is any person or institution, often as a government institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordance ...

*Blockade runners of the American Civil War

The blockade runners of the American Civil War were seagoing Steamships, steam ships that were used to get through the Union blockade that extended some along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coastlines and the lower Mississippi River. The Confe ...

* Letter of marque

*War trophy __NOTOC__

A war trophy is an item taken during warfare by an invading force. Common war trophies include flags, weapons, vehicles, and art.

History

In ancient Greece and ancient Rome, military victories were commemorated with a display of captu ...

*Prize of war

A prize of war is a piece of enemy property or land seized by a belligerent party during or after a war or battle, typically at sea. This term was used nearly exclusively in terms of captured ships during the 18th and 19th centuries. Basis in inte ...

* ''Altmark'' incident

Notes

References

*James Scott Brown (ed.), ''Prize Cases Decided in the United States Supreme Court'' (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1923) *Colombos, ''A Treatise on the Law of Prize'' (London: Longmans, Green & Co. Ltd. 1949) *Gawalt & Kreidler, eds., ''The Journal of Gideon Olmsted'' (Washington DC: Library of Congress 1978) *Grotius, ''De Iure Praedae Commentarius (Commentary on the Law of Prize and Booty)''(Oxford: Clarendon Press 1950) *Edgar Stanton Maclay, ''A History of American Privateers'' (London: S. Low, Marston & Co. 1900) *Donald Petrie, ''The Prize Game: lawful looting on the high seas in the days of fighting sail'' (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1999) *Theodore Richard, Reconsidering the Letter of Marque: Utilizing Private Security Providers Against Piracy (April 1, 2010). Public Contract Law Journal, Vol. 39, No. 3, pp. 411–464 at 429 n.121, Spring 2010. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1591039 *William Morrison Robinson, Jr., ''The Confederate Privateers'' (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 1928) *Lord Russell of Liverpool, ''The French Corsairs'' (London: Robert Hale, 2001) *Carl E. Swanson, ''Predators and Prizes: American Privateering and Imperial Warfare, 1739–1748'' (Columbia, SC: U. South Carolina Press, 1991) *Francis Upton, ''Upton's Maritime Warfare and Prize'' (New York: John Voorhies Law Bookseller and Publisher, 1863)External links

summary of US Prize laws 1868

{{Authority control Law of the sea Prize warfare