Princeton Lecture on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Princeton University is a

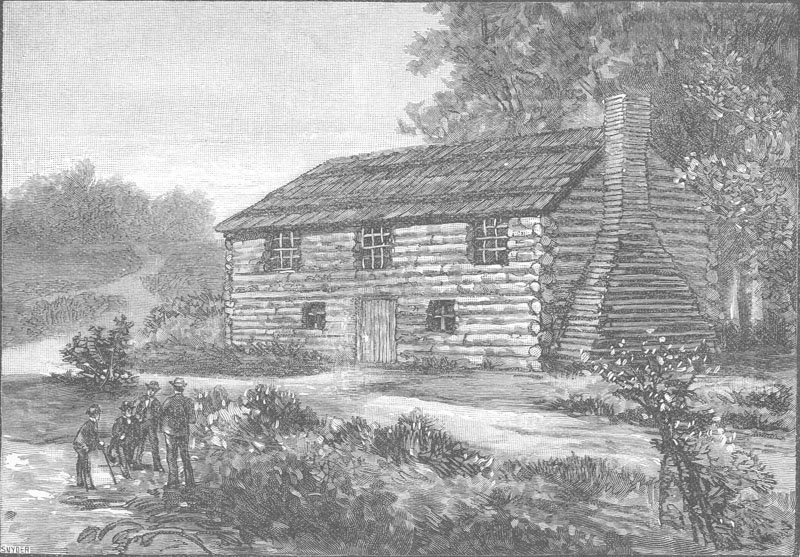

Princeton University, founded as the College of New Jersey, was shaped much in its formative years by the "

Princeton University, founded as the College of New Jersey, was shaped much in its formative years by the "

In 1747, following the death of then President Jonathan Dickinson, the college moved from Elizabeth to

In 1747, following the death of then President Jonathan Dickinson, the college moved from Elizabeth to

Following Patton's resignation,

Following Patton's resignation,

In 1947, three female members of the library staff enrolled in beginner Russian courses to deal with an increase in Russian literature in the library. In 1961, Princeton admitted its first female graduate student, Sabra Follett Meservey, who would go on to be the first woman to earn a master's degree at Princeton. Eight more women enrolled the following year in the Graduate School, and in 1964, T'sai-ying Cheng became the first woman at Princeton to receive a Ph.D. The first undergraduate female students came in 1963 when five women came to Princeton to study "critical languages." They were considered regular students for their year on campus, but were not candidates for a Princeton degree. Following abortive discussions with

In 1947, three female members of the library staff enrolled in beginner Russian courses to deal with an increase in Russian literature in the library. In 1961, Princeton admitted its first female graduate student, Sabra Follett Meservey, who would go on to be the first woman to earn a master's degree at Princeton. Eight more women enrolled the following year in the Graduate School, and in 1964, T'sai-ying Cheng became the first woman at Princeton to receive a Ph.D. The first undergraduate female students came in 1963 when five women came to Princeton to study "critical languages." They were considered regular students for their year on campus, but were not candidates for a Princeton degree. Following abortive discussions with

The main campus consists of more than 200 buildings on in Princeton, New Jersey. The James Forrestal Campus, a smaller location designed mainly as a research and instruction complex, is split between nearby Plainsboro and South Brunswick. The campuses are situated about one hour from both New York City and Philadelphia on the train. The university also owns more than of property in West Windsor Township, and is where Princeton is planning to construct a graduate student housing complex, which will be known as "Lake Campus North".

The first building on campus was Nassau Hall, completed in 1756 and situated on the northern edge of the campus facing Nassau Street. The campus expanded steadily around Nassau Hall during the early and middle 19th century. The McCosh presidency (1868–88) saw the construction of a number of buildings in the

The main campus consists of more than 200 buildings on in Princeton, New Jersey. The James Forrestal Campus, a smaller location designed mainly as a research and instruction complex, is split between nearby Plainsboro and South Brunswick. The campuses are situated about one hour from both New York City and Philadelphia on the train. The university also owns more than of property in West Windsor Township, and is where Princeton is planning to construct a graduate student housing complex, which will be known as "Lake Campus North".

The first building on campus was Nassau Hall, completed in 1756 and situated on the northern edge of the campus facing Nassau Street. The campus expanded steadily around Nassau Hall during the early and middle 19th century. The McCosh presidency (1868–88) saw the construction of a number of buildings in the

Nassau Hall is the oldest building on campus. Begun in 1754 and completed in 1756, it was the first seat of the

Nassau Hall is the oldest building on campus. Begun in 1754 and completed in 1756, it was the first seat of the

Though art collection at the university dates back to its very founding, the

Though art collection at the university dates back to its very founding, the

The

The

Princeton's 20th and current president is Christopher Eisgruber, who was appointed by the university's

Princeton's 20th and current president is Christopher Eisgruber, who was appointed by the university's

Princeton follows a

Princeton follows a

The

The

File:Walker Hall, Wilson College, Princeton University, Princeton NJ.jpg, alt=A picture of First College,

Each residential college has a dining hall for students in the college, and they vary in their environment and food served. Upperclassmen who no longer live in the college can choose from a variety of options: join an

Each residential college has a dining hall for students in the college, and they vary in their environment and food served. Upperclassmen who no longer live in the college can choose from a variety of options: join an

Founded in about 1765, the

Founded in about 1765, the  Princeton is home to a variety of performing arts and music groups. Many of the groups are represented by the Performing Arts Council. Dating back to 1883, the

Princeton is home to a variety of performing arts and music groups. Many of the groups are represented by the Performing Arts Council. Dating back to 1883, the

Current traditions Princeton students celebrate include the ceremonial bonfire, which takes place on the Cannon Green behind Nassau Hall. It is held only if Princeton beats both Harvard University and Yale University at football in the same season. Another tradition is the use of traditional college cheers at events and reunions, like the "Locomotive", which dates back to before 1894. Princeton students abide by the tradition of never exiting the campus through

Current traditions Princeton students celebrate include the ceremonial bonfire, which takes place on the Cannon Green behind Nassau Hall. It is held only if Princeton beats both Harvard University and Yale University at football in the same season. Another tradition is the use of traditional college cheers at events and reunions, like the "Locomotive", which dates back to before 1894. Princeton students abide by the tradition of never exiting the campus through

Princeton supports organized athletics at three levels: varsity intercollegiate, club intercollegiate, and Intramural sports, intramural. It also provides "a variety of physical education and recreational programs" for members of the Princeton community. Most undergraduates participate in athletics at some level. Princeton's colors are orange and black. The school's athletes are known as the ''Tigers'', and the mascot is a tiger. The Princeton administration considered naming the mascot in 2007, but the effort was dropped in the face of alumni opposition.

Princeton supports organized athletics at three levels: varsity intercollegiate, club intercollegiate, and Intramural sports, intramural. It also provides "a variety of physical education and recreational programs" for members of the Princeton community. Most undergraduates participate in athletics at some level. Princeton's colors are orange and black. The school's athletes are known as the ''Tigers'', and the mascot is a tiger. The Princeton administration considered naming the mascot in 2007, but the effort was dropped in the face of alumni opposition.

Princeton hosts 37 men's and women's varsity sports. Princeton is an

Princeton hosts 37 men's and women's varsity sports. Princeton is an

In addition to varsity sports, Princeton hosts 37 club sports teams, which are open to all Princeton students of any skill level. Teams compete against other collegiate teams both in the Northeast and nationally. The intramural sports program is also available on campus, which schedules competitions between residential colleges, eating clubs, independent groups, students, and faculty and staff. Several leagues with differing levels of competitiveness are available.

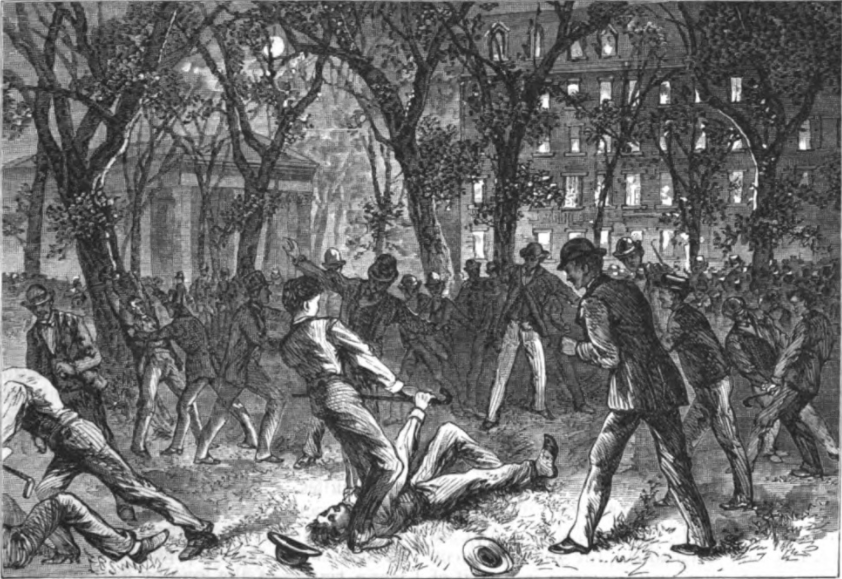

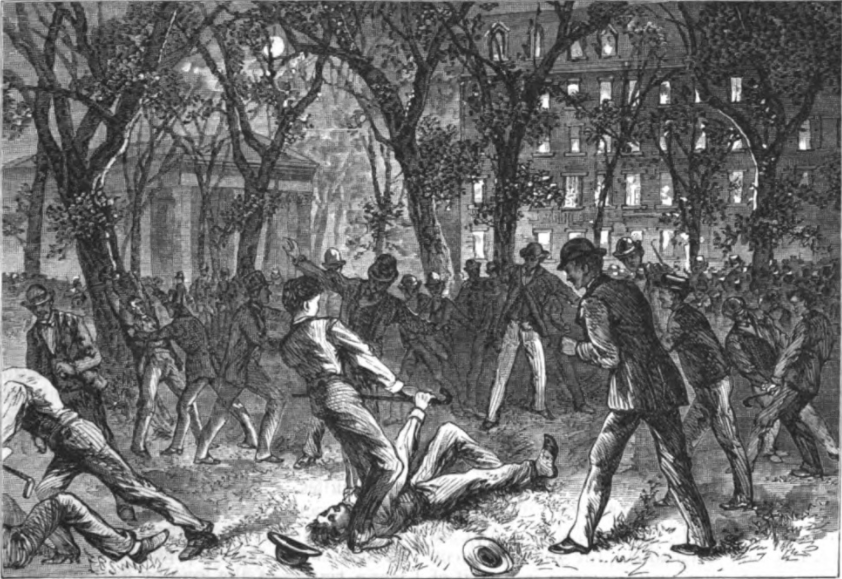

In the fall, freshman and sophomores participate in the intramural athletic competition called Cane Spree. Although the event centers on cane wrestling, freshman and sophomores compete in other sports and competitions. This commemorates a time in the 1870s when sophomores, angry with the freshmen who strutted around with fancy canes, stole all of the canes from the freshmen, hitting them with their own canes in the process.

In addition to varsity sports, Princeton hosts 37 club sports teams, which are open to all Princeton students of any skill level. Teams compete against other collegiate teams both in the Northeast and nationally. The intramural sports program is also available on campus, which schedules competitions between residential colleges, eating clubs, independent groups, students, and faculty and staff. Several leagues with differing levels of competitiveness are available.

In the fall, freshman and sophomores participate in the intramural athletic competition called Cane Spree. Although the event centers on cane wrestling, freshman and sophomores compete in other sports and competitions. This commemorates a time in the 1870s when sophomores, angry with the freshmen who strutted around with fancy canes, stole all of the canes from the freshmen, hitting them with their own canes in the process.

Writers Booth Tarkington,

Writers Booth Tarkington,

Princeton Athletics website

* {{Authority control Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey Educational institutions established in 1746 1746 establishments in New Jersey Colonial colleges Eastern Pennsylvania Rugby Union Universities and colleges in Mercer County, New Jersey Environmental research institutes Private universities and colleges in New Jersey

private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* "In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorded ...

research university

A research university or a research-intensive university is a university that is committed to research as a central part of its mission. They are the most important sites at which knowledge production occurs, along with "intergenerational kno ...

in Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton is a municipality with a borough form of government in Mercer County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton and Princeton Township, both of whi ...

. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States

Higher education in the United States is an optional stage of formal learning following secondary education. Higher education is also referred as post-secondary education, third-stage, third-level, or tertiary education. It covers stages 5 to 8 ...

and one of the nine colonial colleges

The colonial colleges are nine institutions of higher education chartered in the Thirteen Colonies before the United States of America became a sovereign nation after the American Revolution. These nine have long been considered together, notably ...

chartered before the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

. It is one of the highest-ranked universities in the world. The institution moved to Newark in 1747, and then to the current site nine years later. It officially became a university in 1896 and was subsequently renamed Princeton University. It is a member of the Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate athletic conference comprising eight private research universities in the Northeastern United States. The term ''Ivy League'' is typically used beyond the sports context to refer to the eight schoo ...

.

The university is governed by the Trustees of Princeton University

The Trustees of Princeton University is a 40-member board responsible for managing Princeton University's endowment, real estate, instructional programs, and admission. The Trustees include at least 13 members elected by alumni classes, and the Go ...

and has an endowment of $37.7 billion, the largest endowment per student in the United States. Princeton provides undergraduate

Undergraduate education is education conducted after secondary education and before postgraduate education. It typically includes all postsecondary programs up to the level of a bachelor's degree. For example, in the United States, an entry-le ...

and graduate instruction in the humanities

Humanities are academic disciplines that study aspects of human society and culture. In the Renaissance, the term contrasted with divinity and referred to what is now called classics, the main area of secular study in universities at th ...

, social sciences

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of society, societies and the Social relation, relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the o ...

, natural sciences, and engineering

Engineering is the use of scientific method, scientific principles to design and build machines, structures, and other items, including bridges, tunnels, roads, vehicles, and buildings. The discipline of engineering encompasses a broad rang ...

to approximately 8,500 students on its main campus. It offers postgraduate degrees through the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs

The Princeton School of Public and International Affairs (formerly the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs) is a professional public policy school at Princeton University. The school provides an array of comprehensive course ...

, the School of Engineering and Applied Science, the School of Architecture

This is a list of architecture schools at colleges and universities around the world.

An architecture school (also known as a school of architecture or college of architecture), is an institution specializing in architectural education.

Africa

...

and the Bendheim Center for Finance

Bendheim Center for Finance (BCF) is an interdisciplinary center at Princeton University. It was established in 1997 at the initiative of Ben Bernanke and is dedicated to research and education in the area of money and finance, in lieu of there no ...

. The university also manages the Department of Energy's Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory

Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory for plasma physics and nuclear fusion science. Its primary mission is research into and development of fusion as an energy source. It is known ...

and is home to the NOAA's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory

The Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL) is a laboratory in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR). The current director is Dr. Venkatachalam Ramaswamy. It is one of s ...

. It is classified

Classified may refer to:

General

*Classified information, material that a government body deems to be sensitive

*Classified advertising or "classifieds"

Music

*Classified (rapper) (born 1977), Canadian rapper

*The Classified, a 1980s American roc ...

among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity" and has one of the largest university libraries in the world.

Princeton uses a residential college

A residential college is a division of a university that places academic activity in a community setting of students and faculty, usually at a residence and with shared meals, the college having a degree of autonomy and a federated relationship w ...

system and is known for its upperclassmen eating clubs. The university has over 500 student organizations. Princeton students embrace a wide variety of traditions from both the past and present. The university is a NCAA Division I

NCAA Division I (D-I) is the highest level of intercollegiate athletics sanctioned by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in the United States, which accepts players globally. D-I schools include the major collegiate athleti ...

school and competes in the Ivy League. The school's athletic team, the Princeton Tigers

The Princeton Tigers are the athletic teams of Princeton University. The school sponsors 35 varsity teams in 20 sports. The school has won several NCAA national championships, including one in men's fencing, three in women's lacrosse, six in men ...

, has won the most titles in its conference and has sent many students and alumni to the Olympics

The modern Olympic Games or Olympics (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques) are the leading international sporting events featuring summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a var ...

.

As of October 2021, 75 Nobel laureates, 16 Fields Medalists and 16 Turing Award laureates have been affiliated with Princeton University as alumni, faculty members, or researchers. In addition, Princeton has been associated with 21 National Medal of Science

The National Medal of Science is an honor bestowed by the President of the United States to individuals in science and engineering who have made important contributions to the advancement of knowledge in the fields of behavioral and social scienc ...

awardees, 5 Abel Prize

The Abel Prize ( ; no, Abelprisen ) is awarded annually by the King of Norway to one or more outstanding mathematicians. It is named after the Norwegian mathematician Niels Henrik Abel (1802–1829) and directly modeled after the Nobel Pri ...

awardees, 11 National Humanities Medal

The National Humanities Medal is an American award that annually recognizes several individuals, groups, or institutions for work that has "deepened the nation's understanding of the humanities, broadened our citizens' engagement with the human ...

recipients, 215 Rhodes Scholars

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Established in 1902, it is the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. It is considered among the world' ...

and 137 Marshall Scholars

The Marshall Scholarship is a postgraduate scholarship for "intellectually distinguished young Americans ndtheir country's future leaders" to study at any university in the United Kingdom. It is widely considered one of the most prestigious sc ...

. Two U.S. Presidents

The president of the United States is the head of state and head of government of the United States, indirectly elected to a four-year term via the Electoral College. The officeholder leads the executive branch of the federal government and ...

, twelve U.S. Supreme Court Justices (three of whom currently serve on the court) and numerous living industry and media tycoons and foreign heads of state are all counted among Princeton's alumni body. Princeton has graduated many members of the U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

and the U.S. Cabinet

The Cabinet of the United States is a body consisting of the vice president of the United States and the heads of the Federal government of the United States, executive branch's United States federal executive departments, departments in the fed ...

, including eight Secretaries of State, three Secretaries of Defense and two Chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The chairperson, also chairman, chairwoman or chair, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the group ...

.

History

Founding

Princeton University, founded as the College of New Jersey, was shaped much in its formative years by the "

Princeton University, founded as the College of New Jersey, was shaped much in its formative years by the "Log College

The Log College, founded in 1727, was the first theological seminary serving Presbyterians in North America, and was located in what is now Warminster, Pennsylvania. It was founded by William Tennent and operated from 1727 until Tennent's death in ...

", a seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy ...

founded by the Reverend William Tennent

William Tennent (1673 – May 6, 1746) was an early Scottish American Presbyterian minister and educator in British North America.

Early life

Tennent was born in Mid Calder, Linlithgowshire, Scotland, in 1673. He graduated from the Univ ...

at Neshaminy, Pennsylvania

Neshaminy is an unincorporated community in Warrington Township in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, United States. Neshaminy is located at the intersection of Pennsylvania Route 611 and Pennsylvania Route 132

Pennsylvania Route 132 (PA&nbs ...

, in about 1726. While no legal connection ever existed, many of the pupils and adherents from the Log College would go on to financially support and become substantially involved in the early years of the university. While early writers considered it as the predecessor of the university, the idea has been rebuked by Princeton historians.

The founding of the university itself originated from a split in the Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their na ...

church following the Great Awakening

Great Awakening refers to a number of periods of religious revival in American Christian history. Historians and theologians identify three, or sometimes four, waves of increased religious enthusiasm between the early 18th century and the lat ...

. In 1741, New Light

The terms Old Lights and New Lights (among others) are used in Protestant Christian circles to distinguish between two groups who were initially the same, but have come to a disagreement. These terms originated in the early 18th century from a spl ...

Presbyterians were expelled from the Synod of Philadelphia

Synod of the Trinity is an upper judicatory of the Presbyterian Church headquartered in Camp Hill, Pennsylvania. The synod oversees sixteen presbyteries covering all of Pennsylvania, most of West Virginia, and a portion of eastern Ohio.

History ...

in defense of how the Log College ordained ministers. The four founders of the College of New Jersey, who were New Lights, were either expelled or withdrew from the Synod and devised a plan to establish a new college, for they were disappointed with Harvard and Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

's opposition to the Great Awakening and dissatisfied with the limited instruction at the Log College. They convinced three other Presbyterians to join them and decided on New Jersey as the location for the college, as at the time, there was no institution between Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,023 ...

, and the College of William & Mary

The College of William & Mary (officially The College of William and Mary in Virginia, abbreviated as William & Mary, W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia. Founded in 1693 by letters patent issued by King William II ...

in Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 15,425. Located on the Virginia Peninsula, Williamsburg is in the northern part of the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. It is b ...

; it was also where some of the founders preached. Although their initial request was rejected by the Anglican governor Lewis Morrison

Lewis Morrison (September 4, 1844 – August 18, 1906) was a Jamaican-born American stage actor and theatrical manager, born Moritz (or Morris) W. Morris. He was best known for his portrayal of Mephistopheles in his own production of '' Faust'' ...

, the acting governor

An acting governor is a person who acts in the role of governor. In Commonwealth jurisdictions where the governor is a vice-regal position, the role of "acting governor" may be filled by a lieutenant governor (as in most Australian states) or an ...

after Morrison's death, John Hamilton, granted a charter for the College of New Jersey on October 22, 1746. In 1747, approximately five months after acquiring the charter, the trustees elected Jonathan Dickinson

Jonathan Dickinson (1663–1722) was a merchant from Port Royal, Jamaica who was shipwrecked on the southeast coast of Florida in 1696, along with his family and the other passengers and crew members of the ship.

The party was held captive by Job ...

as president and opened in Elizabeth, New Jersey

Elizabeth is a city and the county seat of Union County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.New J ...

, where classes were held in Dickinson's parsonage

A clergy house is the residence, or former residence, of one or more priests or ministers of religion. Residences of this type can have a variety of names, such as manse, parsonage, rectory or vicarage.

Function

A clergy house is typically ow ...

. With its founding, it became the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, and one of nine colonial colleges charted before the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

. The founders aimed for the college to have an expansive curriculum to teach people of various professions, not solely ministerial work. Though the school was open to those of any religious denomination, with many of the founders being of Presbyterian faith, the college became the educational and religious capital of Scotch-Irish Presbyterian America.

Colonial and early years

In 1747, following the death of then President Jonathan Dickinson, the college moved from Elizabeth to

In 1747, following the death of then President Jonathan Dickinson, the college moved from Elizabeth to Newark, New Jersey

Newark ( , ) is the List of municipalities in New Jersey, most populous City (New Jersey), city in the U.S. state of New Jersey and the county seat, seat of Essex County, New Jersey, Essex County and the second largest city within the New Yo ...

, as that was where presidential successor Aaron Burr Sr.

Aaron Burr Sr. (January 4, 1716 – September 24, 1757) was a notable Presbyterian minister and college educator in colonial America. He was a founder of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) and the father of Aaron Burr (1 ...

's parsonage was located. That same year, Princeton's first charter came under dispute by Anglicans, but on September 14, 1748, the recently appointed governor Jonathan Belcher

Jonathan Belcher (8 January 1681/8231 August 1757) was a merchant, politician, and slave trader from colonial Massachusetts who served as both governor of Massachusetts Bay and governor of New Hampshire from 1730 to 1741 and governor of New ...

granted a second charter. Belcher, a Congregationalist, had become alienated from his alma mater, Harvard, and decided to "adopt" the infant college. Belcher would go on to raise funds for the college and donate his 474-volume library, making it one of the largest libraries in the colonies.

In 1756, the college moved again to its present home in Princeton, New Jersey

Princeton is a municipality with a borough form of government in Mercer County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton and Princeton Township, both of whi ...

, because Newark was felt to be too close to New York. Princeton was chosen for its central location in New Jersey and by strong recommendation by Belcher. The college's home in Princeton was Nassau Hall

Nassau Hall, colloquially known as Old Nassau, is the oldest building at Princeton University in Princeton, Mercer County, New Jersey, United States. In 1783 it served as the United States Capitol building for four months. At the time it was built ...

, named for the royal William III of England

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 16508 March 1702), also widely known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from ...

, a member of the House of Orange-Nassau

The House of Orange-Nassau ( Dutch: ''Huis van Oranje-Nassau'', ) is the current reigning house of the Netherlands. A branch of the European House of Nassau, the house has played a central role in the politics and government of the Netherland ...

. The trustees of the College of New Jersey initially suggested that Nassau Hall be named in recognition of Belcher because of his interest in the institution; the governor vetoed the request.

Burr, who would die in 1757, devised a curriculum for the school and enlarged the student body. Following the untimely death of Burr and the college's next three presidents, John Witherspoon

John Witherspoon (February 5, 1723 – November 15, 1794) was a Scottish-American Presbyterian minister, educator, farmer, slaveholder, and a Founding Father of the United States. Witherspoon embraced the concepts of Scottish common sense real ...

became president in 1768 and remained in that post until his death in 1794. With his presidency, Witherspoon focused the college on preparing a new generation of both educated clergy and secular leadership in the new American nation. To this end, he tightened academic standards, broadened the curriculum, solicited investment for the college, and grew its size.

A signer of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of ...

, Witherspoon and his leadership led the college to becoming influential to the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

. In 1777, the college became the site for the Battle of Princeton

The Battle of Princeton was a battle of the American Revolutionary War, fought near Princeton, New Jersey on January 3, 1777, and ending in a small victory for the Colonials. General Lord Cornwallis had left 1,400 British troops under the comm ...

. During the battle, British soldiers briefly occupied Nassau Hall before eventually surrendering to American forces led by General George Washington. During the summer and fall of 1783, the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

and Washington met in Nassau Hall, making Princeton the country's capital for four months; Nassau Hall is where Congress learned of the peace treaty between the colonies and the British. The college did suffer from the revolution, with a depreciated endowment

Endowment most often refers to:

*A term for human penis size

It may also refer to: Finance

*Financial endowment, pertaining to funds or property donated to institutions or individuals (e.g., college endowment)

*Endowment mortgage, a mortgage to b ...

and hefty repair bills for Nassau Hall.

19th century

In 1795, PresidentSamuel Stanhope Smith

Samuel Stanhope Smith (March 15, 1751 – August 21, 1819) was a Presbyterianism, Presbyterian minister, founding president of Hampden–Sydney College and the seventh president of the College of New Jersey (now History of Princeton University, Pr ...

took office, the first alumnus to become president. Nassau Hall suffered a large fire that destroyed its interior in 1802, which Smith blamed on rebellious students. The college raised funds for reconstruction, as well as the construction of two new buildings. In 1807, a large student riot occurred at Nassau Hall, spurred by underlying distrust of educational reforms by Smith away from the Church. Following Smith's mishandling of the situation, falling enrollment, and faculty resignations, the trustees of the university offered resignation to Smith, which he accepted. In 1812, Ashbel Green

Ashbel Green (July 6, 1762 – May 19, 1848) was an American Presbyterian minister and academic.

Biography

Born in Hanover Township, New Jersey, Green served as a sergeant of the New Jersey militia during the American Revolutionary War, and we ...

was unanimously elected by the trustees of the College to become the eighth president. After the liberal tenure of Smith, Green represented the conservative "Old Side," in which he introduced rigorous disciplinary rules and heavily embraced religion. Even so, believing the College was not religious enough, he took a prominent role in establishing the Princeton Theological Seminary

Princeton Theological Seminary (PTSem), officially The Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church, is a private school of theology in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1812 under the auspices of Archibald Alexander, the General Assembly o ...

next door. While student riots were a frequent occurrence during Green's tenure, enrollment did increase under his administration.

In 1823, James Carnahan

James Carnahan (November 15, 1775 – March 2, 1859) was an American clergyman and educator who served as the ninth President of Princeton University.

Born in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, Carnahan was an 1800 graduate of the school when it w ...

became president, arriving as an unprepared and timid leader. With the college riven by conflicting views between students, faculty, and trustees, and enrollment hitting its lowest in years, Carnahan considered closing the university. Carnahan's successor, John Maclean Jr., who was only a professor at the time, recommended saving the university with the help of alumni; as a result, Princeton's alumni association, led by James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

, was created and began raising funds. With Carnahan and Maclean, now vice-president, working as partners, enrollment and faculty increased, tensions decreased, and the college campus expanded. Maclean took over the presidency in 1854 and led the university through the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

. When Nassau Hall burned down again in 1855, Maclean raised funds and used the money to rebuild Nassau Hall and run the university on an austerity

Austerity is a set of political-economic policies that aim to reduce government budget deficits through spending cuts, tax increases, or a combination of both. There are three primary types of austerity measures: higher taxes to fund spendi ...

budget during the war years. With a third of students from the college being from the South, enrollment fell. Once many of the Southerners left, the campus became a sharp proponent for the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

, even bestowing an honorary degree to President Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

.

James McCosh

James McCosh (April 1, 1811 – November 16, 1894) was a philosopher of the Scottish School of Common Sense. He was president of Princeton University 1868–88.

Biography

McCosh was born into a Covenanting family in Ayrshire, an ...

became the college's president in 1868 and lifted the institution out of a low period that had been brought about by the war. During his two decades of service, he overhauled the curriculum, oversaw an expansion of inquiry into the sciences, recruited distinguished faculty, and supervised the addition of a number of buildings in the High Victorian Gothic

High Victorian Gothic was an eclectic architectural style and movement during the mid-late 19th century. It is seen by architectural historians as either a sub-style of the broader Gothic Revival style, or a separate style in its own right.

Prom ...

style to the campus. McCosh's tenure also saw the creation and rise of many extracurricular activities, like the Princeton Glee Club

The Princeton University Glee Club is the oldest and most prestigious choir at Princeton University, composed of approximately 100 mixed voices. They give multiple performances throughout the year featuring music from Renaissance to Modern, and ...

, the Triangle Club

The Princeton Triangle Club is a theater troupe at Princeton University. Founded in 1891, it is one of the oldest collegiate theater troupes in the United States. Triangle

premieres an original student-written musical every year, and then takes ...

, the first intercollegiate football team, and the first permanent eating club

A dining club (UK) or eating club (US) is a social group, usually requiring membership (which may, or may not be available only to certain people), which meets for dinners and discussion on a regular basis. They may also often have guest speakers. ...

, as well as the elimination of fraternities and sororities. In 1879, Princeton conferred its first doctorates

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''l ...

on James F. Williamson and William Libby, both members of the Class of 1877.

Francis Patton

Francis Landey Patton (January 22, 1843 – November 25, 1932) was a Bermudan-American educator, Presbyterian minister, academic administrator, and theologian, and served as the twelfth president of Princeton University.

Background, 1843–1871

...

took the presidency in 1888, and although his election was not met by unanimous enthusiasm, he was well received by undergraduates. Patton's administration was marked with great change, for Princeton's enrollment and faculty had doubled. At the same time, the college underwent large expansion and social life was changing in reflection of the rise in eating clubs and burgeoning interest in athletics. In 1893, the honor system was established, allowing for unproctored exams. In 1896, the college officially became a university, and as a result, it officially changed its name to Princeton University. In 1900, the Graduate School

Postgraduate or graduate education refers to academic or professional degrees, certificates, diplomas, or other qualifications pursued by post-secondary students who have earned an undergraduate (bachelor's) degree.

The organization and st ...

was formally established. Even with such accomplishments, Patton's administration remained lackluster with its administrative structure and towards its educational standards. Due to profile changes in the board of trustees and dissatisfaction with his administration, he was forced to resign in 1902.

20th century

Following Patton's resignation,

Following Patton's resignation, Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of P ...

, an alumnus and popular professor, was elected the 13th president of the university. Noticing falling academic standards, Wilson orchestrated significant changes to the curriculum, where freshman and sophomores followed a unified curriculum while juniors and seniors concentrated study in one discipline. Ambitious seniors were allowed to undertake independent work, which would eventually shape Princeton's emphasis on the practice for the future. Wilson further reformed the educational system by introducing the preceptorial system in 1905, a then-unique concept in the United States that augmented the standard lecture method of teaching with a more personal form in which small groups of students, or precepts, could interact with a single instructor, or preceptor, in their field of interest. The changes brought about many new faculty and cemented Princeton's academics for the first half of the 20th century. Due to the tightening of academic standards, enrollment declined severely until 1907. In 1906, the reservoir Lake Carnegie

Lake Carnegie is a reservoir that is formed from a dam on the Millstone River, in the far northeastern corner of Princeton, Mercer County, New Jersey. The Delaware and Raritan Canal and its associated tow path are situated along the eastern sho ...

was created by Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans in ...

, and the university officially became nonsectarian

Nonsectarian institutions are secular institutions or other organizations not affiliated with or restricted to a particular religious group.

Academic sphere

Examples of US universities that identify themselves as being nonsectarian include Adelp ...

. Before leaving office, Wilson strengthened the science program to focus on "pure" research and broke the Presbyterian lock on the board of trustees. However, he did fail in winning support for the permanent location of the Graduate School and the elimination of the eating clubs, which he proposed replacing with quadrangles, a precursor to the residential college system. Wilson also continued to keep Princeton closed off from accepting Black students. When an aspiring Black student wrote a letter to Wilson, he got his secretary to reply telling him to attend a university where he would be more welcome.

John Grier Hibben

John Grier Hibben (April 19, 1861 – May 16, 1933) was a Presbyterian minister, a philosopher, and educator. He served as president of Princeton University from 1912–1932, succeeding Woodrow Wilson and implementing many of the reforms ...

became president in 1912 and would remain in the post for two decades. On October 2, 1913, the Princeton University Graduate College

The Graduate College at Princeton University is a residential college which serves as the center of graduate student life at Princeton. Wyman House, adjacent to the Graduate College, serves as the official residence of the current Dean of the Gr ...

was dedicated. When the United States entered World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

in 1917, Hibben allocated all available University resources to the government. As a result, military training schools opened on campus and laboratories and other facilities were used for research and operational programs. Overall, more than 6,000 students served in the armed forces, with 151 dying during the war. After the war, enrollment spiked and the trustees established the system of selective admission in 1922. From the 1920s to the 1930s, the student body featured many students from preparatory schools, zero Black students, and dwindling Jewish enrollment because of quotas. Aside from managing Princeton during WWI, Hibben introduced the senior thesis in 1923 as a part of The New Plan of Study. He also brought about great expansion to the university, with the creation of the School of Architecture in 1919, the School of Engineering in 1921, and the School of Public and International Affairs in 1930. By the end of his presidency, the endowment had increased by 374 percent, the total area of the campus doubled, the faculty experienced impressive growth, and the enrollment doubled.

Hibben's successor, Harold Willis Dodds

Harold Willis Dodds (June 28, 1889 – October 25, 1980) was the fifteenth president of Princeton University from 1933 to 1957.

Early life and education

Dodds was born on June 28, 1889, in Utica, Pennsylvania, the son of a professor of Bible ...

would lead the university through the Great Depression, World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, and the Korean Conflict

The Korean conflict is an ongoing conflict based on the division of Korea between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) and South Korea (Republic of Korea), both of which claim to be the sole legitimate government of all of Korea ...

. With the Great Depression, many students were forced to withdraw due to financial reasons. At the same time, Princeton's reputation in physics and mathematics surged as many European scientists left for the United States due to uneasy tension caused by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. In 1930, the Institute for Advanced Study

The Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), located in Princeton, New Jersey, in the United States, is an independent center for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry. It has served as the academic home of internationally preeminent scholar ...

was founded to provide a space for the influx of scientists, such as Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

. Many Princeton scientists would work on the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

during the war, including the entire physics department. During World War II, Princeton offered an accelerated program for students to graduate early before entering the armed forces. Student enrollment fluctuated from month to month, and many faculty were forced to teach unfamiliar subjects. Still, Dodds maintained academic standards and would establish a program for servicemen, so they could resume their education once discharged.

1945 to present

Post-war years saw scholars renewing broken bonds through numerous conventions, expansion of the campus, and the introduction of distribution requirements. The period saw the desegregation of Princeton, which was stimulated by changes to the New Jersey constitution. Princeton began undertaking a sharper focus towards research in the years after the war, with the construction of Firestone Library in 1948 and the establishment of the Forrestal Research Center in the 1950s. Government sponsored research increased sharply, particularly in the physics and engineering departments, with much of it occurring at the new Forrestal campus. Though, as the years progressed, scientific research at the Forrestal campus declined, and in 1973, some of the land was converted to commercial and residential spaces. Robert Goheen would succeed Dodds by unanimous vote and serve as president until 1972. Goheen's presidency was characterized as being more liberal than previous presidents, and his presidency would see a rise in Black applicants, as well as the eventual coeducation of the university in 1969. During this period of rising diversity, the Third World Center (now known as the Carl A. Fields Center) was dedicated in 1971. Goheen also oversaw great expansion for the university, with square footage increasing by 80 percentage. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Princeton experienced unprecedented activism, with most of it centered on theVietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

. While Princeton activism initially remained relatively timid compared to other institutions, protests began to grow with the founding of a local chapter of Students for a Democratic Society

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was a national student activist organization in the United States during the 1960s, and was one of the principal representations of the New Left. Disdaining permanent leaders, hierarchical relationships ...

(SDS) in 1965, which organized many of the later Princeton protests. In 1966, the SDS gained prominence on campus following picketing

Picketing is a form of protest in which people (called pickets or picketers) congregate outside a place of work or location where an event is taking place. Often, this is done in an attempt to dissuade others from going in (" crossing the pic ...

against a speech by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

, which gained frontpage coverage by the ''New York Times.'' A notable point of contention on campus was the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA) and would feature multiple protests, some of which required police action. As the years went on, the protests' agenda broadened to investments in South Africa, environmental issues, and women's rights. In response to these broadening protests, the Council of the Princeton University Community (CPUC) was founded to serve as a method for greater student voice in governance. Activism culminated in 1970 with a student, faculty, and staff member strike

Strike may refer to:

People

* Strike (surname)

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

*Airstrike, military strike by air forces on either a suspected ...

, so the university could become an "institution against expansion of the war." Princeton's protests would taper off later that year, with ''The'' ''Daily Princetonian'' saying that, "Princeton 1970–71 was an emotionally burned out university."

In 1982, the residential college system was officially established under Goheen's successor William G. Bowen

William Gordon Bowen (; October 6, 1933October 20, 2016) was an American academic who served as the president emeritus of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, serving as its president from 1988 to 2006. From 1972 until 1988, he was the president o ...

, who would serve until 1988. During his presidency, Princeton's endowment increased from $625 million to $2 billion, and a major fundraising drive known as "A Campaign for Princeton" was conducted. President Harold T. Shapiro

Harold Tafler Shapiro (born June 8, 1935) is an economist and university administrator. He is currently a professor of economics and public affairs at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University. Shapiro serv ...

would succeed Bowen and remain president until 2001. Shapiro would continue to increase the endowment, expand academic programs, raise student diversity, and oversaw the most renovations in Princeton's history. In 2001, Princeton shifted the financial aid policy to a system that replaced all loans with grants. That same year, Princeton elected its first female president, Shirley M. Tilghman. Before retiring in 2012, Tilghman expanded financial aid offerings and conducted several major construction projects like the Lewis Center for the Arts and a sixth residential college. Tilghman also lead initiatives for more global programs, the creation of an office of sustainability, and investments into the sciences.

Princeton's 20th and current president Christopher Eisgruber was elected in 2013. In 2017, Princeton University unveiled a large-scale public history Public history is a broad range of activities undertaken by people with some training in the discipline of history who are generally working outside of specialized academic settings. Public history practice is deeply rooted in the areas of historic ...

and digital humanities

Digital humanities (DH) is an area of scholarly activity at the intersection of computing or digital technologies and the disciplines of the humanities. It includes the systematic use of digital resources in the humanities, as well as the analy ...

investigation into its historical involvement with slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

called the Princeton & Slavery Project. The project saw the publication of hundreds of primary sources, 80 scholarly essays, a scholarly conference, a series of short plays, and an art project. In April 2018, university trustees announced that they would name two public spaces for James Collins Johnson and Betsey Stockton

Betsey Stockton (c. 1798–1865), sometimes spelled Betsy Stockton, was an American educator and missionary in Hawaii.

Life

Betsey was born into slavery in Princeton, New Jersey, about the year 1798. While she was a child, her owner Robert Stockt ...

, enslaved people who lived and worked on Princeton's campus and whose stories were publicized by the project. In 2019, large-scale student activism again entered the mainstream concerning the school's implementation of federal Title IX

Title IX is the most commonly used name for the federal civil rights law in the United States that was enacted as part (Title IX) of the Education Amendments of 1972. It prohibits sex-based discrimination in any school or any other educa ...

policy relating to Campus sexual assault

Campus sexual assault is the sexual assault, including rape, of a student while attending an institution of higher learning, such as a college or university. The victims of such assaults are more likely to be female, but any gender can be vi ...

. The activism consisted of sit-ins

A sit-in or sit-down is a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area for a protest, often to promote political, social, or economic change. The protestors gather conspicuously in a space or building, refusing to mo ...

in response to a student's disciplinary sentence.

Coeducation

The roots ofcoeducation

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to ...

at the university date back to the 19th century. Founded in 1887, the Evelyn College for Women

Evelyn College for Women, often shortened to Evelyn College, was the coordinate women's college of Princeton University in Princeton, New Jersey between 1887 and 1897. It was the first women's college in the State of New Jersey.

Background

Evely ...

in Princeton provided education to largely the daughters of professors and sisters of Princeton undergraduates. While no legal connection ever existed, many Princeton professors taught there and several Princeton administrations, like Francis Patton, were part of its board of trustees. It closed in 1897 following the death of its founder, Joshua McIlvaine.

In 1947, three female members of the library staff enrolled in beginner Russian courses to deal with an increase in Russian literature in the library. In 1961, Princeton admitted its first female graduate student, Sabra Follett Meservey, who would go on to be the first woman to earn a master's degree at Princeton. Eight more women enrolled the following year in the Graduate School, and in 1964, T'sai-ying Cheng became the first woman at Princeton to receive a Ph.D. The first undergraduate female students came in 1963 when five women came to Princeton to study "critical languages." They were considered regular students for their year on campus, but were not candidates for a Princeton degree. Following abortive discussions with

In 1947, three female members of the library staff enrolled in beginner Russian courses to deal with an increase in Russian literature in the library. In 1961, Princeton admitted its first female graduate student, Sabra Follett Meservey, who would go on to be the first woman to earn a master's degree at Princeton. Eight more women enrolled the following year in the Graduate School, and in 1964, T'sai-ying Cheng became the first woman at Princeton to receive a Ph.D. The first undergraduate female students came in 1963 when five women came to Princeton to study "critical languages." They were considered regular students for their year on campus, but were not candidates for a Princeton degree. Following abortive discussions with Sarah Lawrence College

Sarah Lawrence College is a private liberal arts college in Yonkers, New York. The college models its approach to education after the Oxford/Cambridge system of one-on-one student-faculty tutorials. Sarah Lawrence scholarship, particularly i ...

to relocate the women's college to Princeton and merge it with the university in 1967, the administration commissioned a report on admitting women. The final report was issued in January 1969, supporting the idea. That same month, the trustees voted 24–8 in favor of coeducation and began preparing the institution for the transition. The university finished these plans in April 1969 and announced there would be coeducation in September. Ultimately, 101 female freshman and 70 female transfer students enrolled at Princeton in September 1969. Those admitted were housed in Pyne Hall, a fairly isolated dormitory; a security system were added, although the women deliberately broke it within a day.

In 1971, Mary St. John Douglas and Susan Savage Speers became the first female trustees, and in 1974 quotas for men and women were eliminated. Following a 1979 lawsuit, the eating clubs were required to go coeducational in 1991 after an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point ...

was denied. In 2001, Princeton elected its first female president.

Campus

The main campus consists of more than 200 buildings on in Princeton, New Jersey. The James Forrestal Campus, a smaller location designed mainly as a research and instruction complex, is split between nearby Plainsboro and South Brunswick. The campuses are situated about one hour from both New York City and Philadelphia on the train. The university also owns more than of property in West Windsor Township, and is where Princeton is planning to construct a graduate student housing complex, which will be known as "Lake Campus North".

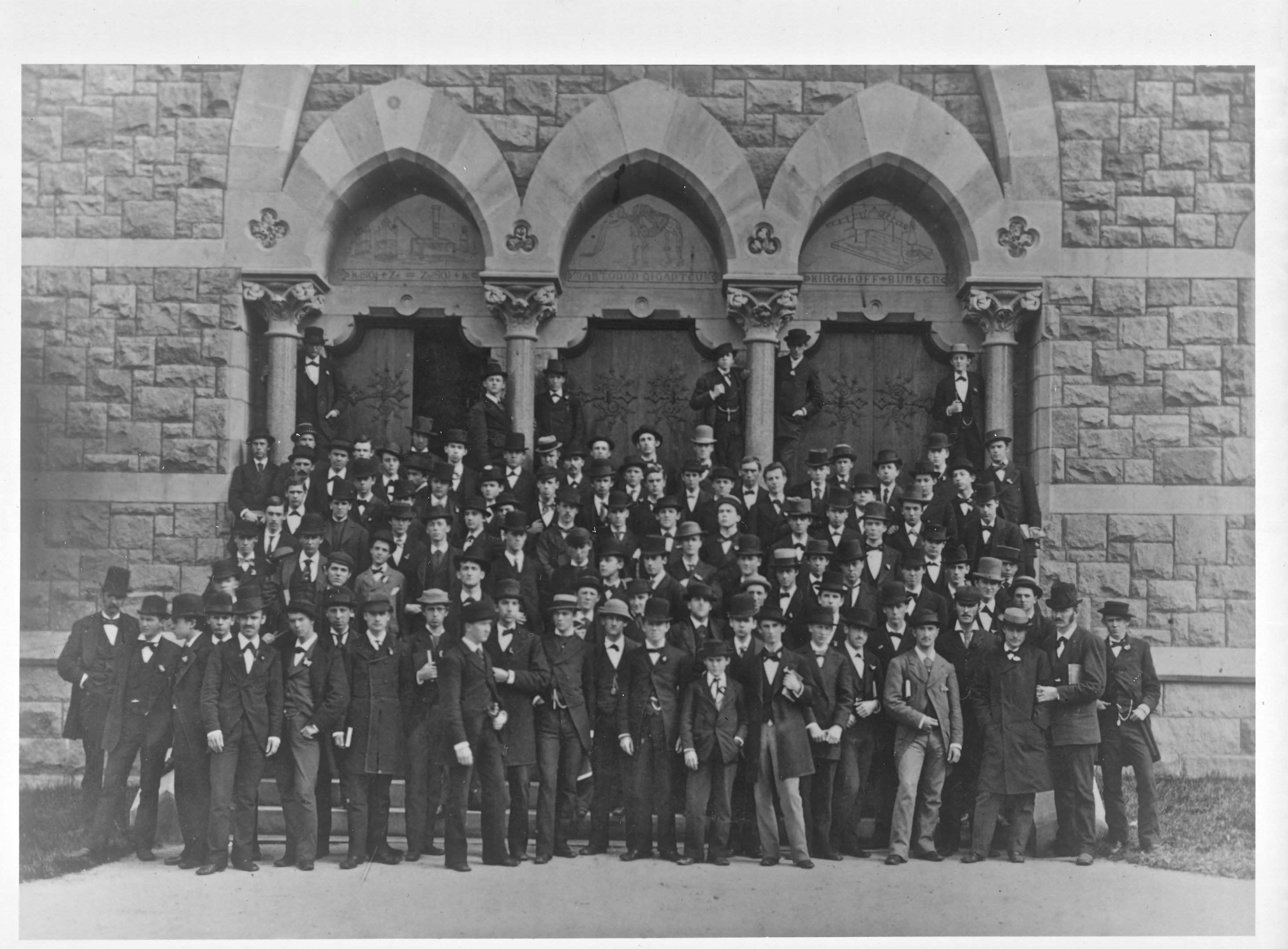

The first building on campus was Nassau Hall, completed in 1756 and situated on the northern edge of the campus facing Nassau Street. The campus expanded steadily around Nassau Hall during the early and middle 19th century. The McCosh presidency (1868–88) saw the construction of a number of buildings in the

The main campus consists of more than 200 buildings on in Princeton, New Jersey. The James Forrestal Campus, a smaller location designed mainly as a research and instruction complex, is split between nearby Plainsboro and South Brunswick. The campuses are situated about one hour from both New York City and Philadelphia on the train. The university also owns more than of property in West Windsor Township, and is where Princeton is planning to construct a graduate student housing complex, which will be known as "Lake Campus North".

The first building on campus was Nassau Hall, completed in 1756 and situated on the northern edge of the campus facing Nassau Street. The campus expanded steadily around Nassau Hall during the early and middle 19th century. The McCosh presidency (1868–88) saw the construction of a number of buildings in the High Victorian Gothic

High Victorian Gothic was an eclectic architectural style and movement during the mid-late 19th century. It is seen by architectural historians as either a sub-style of the broader Gothic Revival style, or a separate style in its own right.

Prom ...

and Romanesque Revival

Romanesque Revival (or Neo-Romanesque) is a style of building employed beginning in the mid-19th century inspired by the 11th- and 12th-century Romanesque architecture. Unlike the historic Romanesque style, Romanesque Revival buildings tended to ...

styles, although many of them are now gone, leaving the remaining few to appear out of place. At the end of the 19th century, much of Princeton's architecture was designed by the Cope and Stewardson

Cope and Stewardson (1885–1912) was a Philadelphia architecture firm founded by Walter Cope and John Stewardson, and best known for its Collegiate Gothic building and campus designs. Cope and Stewardson established the firm in 1885, and were jo ...

firm (the same architects who designed a large part of Washington University in St. Louis

Washington University in St. Louis (WashU or WUSTL) is a private research university with its main campus in St. Louis County, and Clayton, Missouri. Founded in 1853, the university is named after George Washington. Washington University i ...

and University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universit ...

) resulting in the Collegiate Gothic

Collegiate Gothic is an architectural style subgenre of Gothic Revival architecture, popular in the late-19th and early-20th centuries for college and high school buildings in the United States and Canada, and to a certain extent Euro ...

style for which the university is known for today. Implemented initially by William Appleton Potter

William Appleton Potter (December 10, 1842 – February 19, 1909) was an American architect who designed numerous buildings for Princeton University, as well as municipal offices and churches. He served as a Supervising Architect of the Treasury ...

, and later enforced by the university's supervising architect, Ralph Adams Cram

Ralph Adams Cram (December 16, 1863 – September 22, 1942) was a prolific and influential American architect of collegiate and Church (building), ecclesiastical buildings, often in the Gothic Revival architecture, Gothic Revival style. Cram and ...

, the Collegiate Gothic style remained the standard for all new building on the Princeton campus until 1960. A flurry of construction projects in the 1960s produced a number of new buildings on the south side of the main campus, many of which have been poorly received. Several prominent architects have contributed some more recent additions, including Frank Gehry

Frank Owen Gehry, , FAIA (; ; born ) is a Canadian-born American architect and designer. A number of his buildings, including his private residence in Santa Monica, California, have become world-renowned attractions.

His works are considere ...

(Lewis Library), I. M. Pei

Ieoh Ming Pei

– website of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners ( ; ; April 26, 1917 – May 16, 2019) was ...

(Spelman Halls), – website of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners ( ; ; April 26, 1917 – May 16, 2019) was ...

Demetri Porphyrios

Demetri Porphyrios ( el, Δημήτρης Πορφυρίου; born 1949) is a Greek architect and author who practices architecture in London as principal of the firm Porphyrios Associates. In addition to his architectural practice and writing, ...

(Whitman College

Whitman College is a private liberal arts college in Walla Walla, Washington. The school offers 53 majors and 33 minors in the liberal arts and sciences, and it has a student-to-faculty ratio of 9:1. Whitman was the first college in the Pacifi ...

, a Collegiate Gothic project), Robert Venturi

Robert Charles Venturi Jr. (June 25, 1925 – September 18, 2018) was an American architect, founding principal of the firm Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, and one of the major architectural figures of the twentieth century.

Together with ...

and Denise Scott Brown

Denise Scott Brown (née Lakofski; born October 3, 1931) is an American architect, planner, writer, educator, and principal of the firm Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates in Philadelphia. Scott Brown and her husband and partner, Robert Venturi, ...

(Frist Campus Center

Frist Campus Center is a focal point of social life at Princeton University. The campus center is a combination of the former Palmer Physics Lab, and a modern addition completed in 2001. It was endowed with money from the fortune the Frist famil ...

, among several others), Minoru Yamasaki

was an American architect, best known for designing the original World Trade Center in New York City and several other large-scale projects. Yamasaki was one of the most prominent architects of the 20th century. He and fellow architect Edward ...

(Robertson Hall), and Rafael Viñoly

Rafael Viñoly Beceiro (born 1944) is a Uruguayan architect. He is the principal of Rafael Viñoly Architects, which he founded in 1983. The firm has offices in New York City, Palo Alto, London, Manchester, Abu Dhabi, and Buenos Aires.

Vi� ...

(Carl Icahn

Carl Celian Icahn (; born February 16, 1936) is an American financier. He is the founder and controlling shareholder of Icahn Enterprises, a public company and diversified conglomerate holding company based in Sunny Isles Beach. Icahn takes l ...

Laboratory).

A group of 20th-century sculptures scattered throughout the campus forms the Putnam Collection of Sculpture. It includes works by Alexander Calder

Alexander Calder (; July 22, 1898 – November 11, 1976) was an American sculptor known both for his innovative mobiles (kinetic sculptures powered by motors or air currents) that embrace chance in their aesthetic, his static "stabiles", and his ...

(''Five Disks: One Empty''), Jacob Epstein

Sir Jacob Epstein (10 November 1880 – 21 August 1959) was an American-British sculptor who helped pioneer modern sculpture. He was born in the United States, and moved to Europe in 1902, becoming a British subject in 1911.

He often produc ...

(''Albert Einstein''), Henry Moore

Henry Spencer Moore (30 July 1898 – 31 August 1986) was an English artist. He is best known for his semi-abstract art, abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art. As well as sculpture, Mo ...

(''Oval with Points

''Oval with Points'' is a series of enigmatic abstract sculptures by British sculptor Henry Moore, made in plaster and bronze from 1968 to 1970, from a maquette in 1968 (LH 594) made in plaster and then cast in bronze, through a working model in ...

''), Isamu Noguchi

was an American artist and landscape architect whose artistic career spanned six decades, from the 1920s onward. Known for his sculpture and public artworks, Noguchi also designed stage sets for various Martha Graham productions, and several ...

(''White Sun''), and Pablo Picasso

Pablo Ruiz Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist and theatre designer who spent most of his adult life in France. One of the most influential artists of the 20th century, he is ...

(''Head of a Woman''). Richard Serra

Richard Serra (born November 2, 1938) is an American artist known for his large-scale sculptures made for site-specific landscape, urban, and architectural settings. Serra's sculptures are notable for their material quality and exploration of ...

's ''The Hedgehog and The Fox

''The Hedgehog and the Fox'' is an essay by philosopher Isaiah Berlin that was published as a book in 1953. It was one of his most popular essays with the general public. However, Berlin said, "I meant it as a kind of enjoyable intellectual gam ...

'' is located between Peyton and Fine halls next to Princeton Stadium and the Lewis Library.

At the southern edge of the campus is Lake Carnegie, an artificial lake named for Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie financed the lake's construction in 1906 at the behest of a friend and his brother who were both Princeton alumni. Carnegie hoped the opportunity to take up rowing would inspire Princeton students to forsake football, which he considered "not gentlemanly." The Shea Rowing Center

The C. Bernard Shea Rowing Center is the boathouse for the Princeton University rowing programs. Located on Lake Carnegie in Princeton, New Jersey, the center consists of the Class of 1887 Boathouse and the Richard Ottesen Prentke ‘67 Training ...

on the lake's shore continues to serve as the headquarters for Princeton rowing.

Princeton's grounds were designed by Beatrix Farrand

Beatrix Cadwalader Farrand (née Jones; June 19, 1872 – February 28, 1959) was an American landscape gardener and landscape architect. Her career included commissions to design about 110 gardens for private residences, estates and country hom ...

between 1912 and 1943. Her contributions were most recently recognized with the naming of a courtyard for her. Subsequent changes to the landscape were introduced by Quennell Rothschild & Partners in 2000. In 2005, Michael Van Valkenburgh

Michael Robert Van Valkenburgh (born September 5, 1951) is an American landscape architect and educator. He has worked on a wide variety of projects in the United States, Canada, Korea, and France, including public parks, college campuses, sculpt ...

was hired as the new consulting landscape architect for Princeton's 2016 Campus Plan. Lynden B. Miller was invited to work with him as Princeton's consulting gardening architect, focusing on the 17 gardens that are distributed throughout the campus.

Buildings

Nassau Hall

Nassau Hall is the oldest building on campus. Begun in 1754 and completed in 1756, it was the first seat of the

Nassau Hall is the oldest building on campus. Begun in 1754 and completed in 1756, it was the first seat of the New Jersey Legislature

The New Jersey Legislature is the legislative branch of the government of the U.S. state of New Jersey. In its current form, as defined by the New Jersey Constitution of 1947, the Legislature consists of two houses: the General Assembly and th ...

in 1776, was involved in the Battle of Princeton in 1777, and was the seat of the Congress of the Confederation

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States of America during the Confederation period, March 1, 1781 – Mar ...

(and thus capitol of the United States) from June 30, 1783, to November 4, 1783. Since 1911, the front entrance has been flanked by two bronze tigers, a gift of the Princeton Class of 1879, which replaced two lions previously given in 1889. Starting in 1922, commencement has been held on the front lawn of Nassau Hall when there is good weather. In 1966, Nassau Hall was added to the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artist ...

. Nowadays, it houses the office of the university president and other administrative offices.

To the south of Nassau Hall lies a courtyard that is known as Cannon Green. Buried in the ground at the center is the "Big Cannon," which was left in Princeton by British troops as they fled following the Battle of Princeton. It remained in Princeton until the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It ...

, when it was taken to New Brunswick

New Brunswick (french: Nouveau-Brunswick, , locally ) is one of the thirteen Provinces and territories of Canada, provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic Canad ...

. In 1836, the cannon was returned to Princeton and placed at the eastern end of town. Two years later, it was moved to the campus under cover of night by Princeton students, and in 1840, it was buried in its current location. A second "Little Cannon" is buried in the lawn in front of nearby Whig Hall. The cannon, which may also have been captured in the Battle of Princeton, was stolen by students of Rutgers University

Rutgers University (; RU), officially Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, is a public land-grant research university consisting of four campuses in New Jersey. Chartered in 1766, Rutgers was originally called Queen's College, and wa ...

in 1875. The theft ignited the Rutgers-Princeton Cannon War. A compromise between the presidents of Princeton and Rutgers ended the war and forced the return of the Little Cannon to Princeton. The protruding cannons are occasionally painted scarlet by Rutgers students who continue the traditional dispute.

Art Museum

Princeton University Art Museum

The Princeton University Art Museum (PUAM) is the Princeton University gallery of art, located in Princeton, New Jersey. With a collecting history that began in 1755, the museum was formally established in 1882, and now houses over 113,000 works o ...

wasn't officially established until 1882 by President McCosh. Its establishment arose from a desire to provide direct access to works of art in a museum for a curriculum in the arts, an education system familiar to many European universities at the time. The museum took on the purposes of providing "exposure to original works of art and to teach the history of art through an encyclopedic collection of world art."

Numbering over 112,000 objects, the collections range from ancient to contemporary art and come from Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas. The museum's art is divided into ten extensive curatorial areas. There is a collection of Greek and Roman antiquities

Antiquities are objects from antiquity, especially the civilizations of the Mediterranean: the Classical antiquity of Greece and Rome, Ancient Egypt and the other Ancient Near Eastern cultures. Artifacts from earlier periods such as the Meso ...

, including ceramics, marbles, bronzes, and Roman mosaics from faculty excavations in Antioch