Primo Levi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

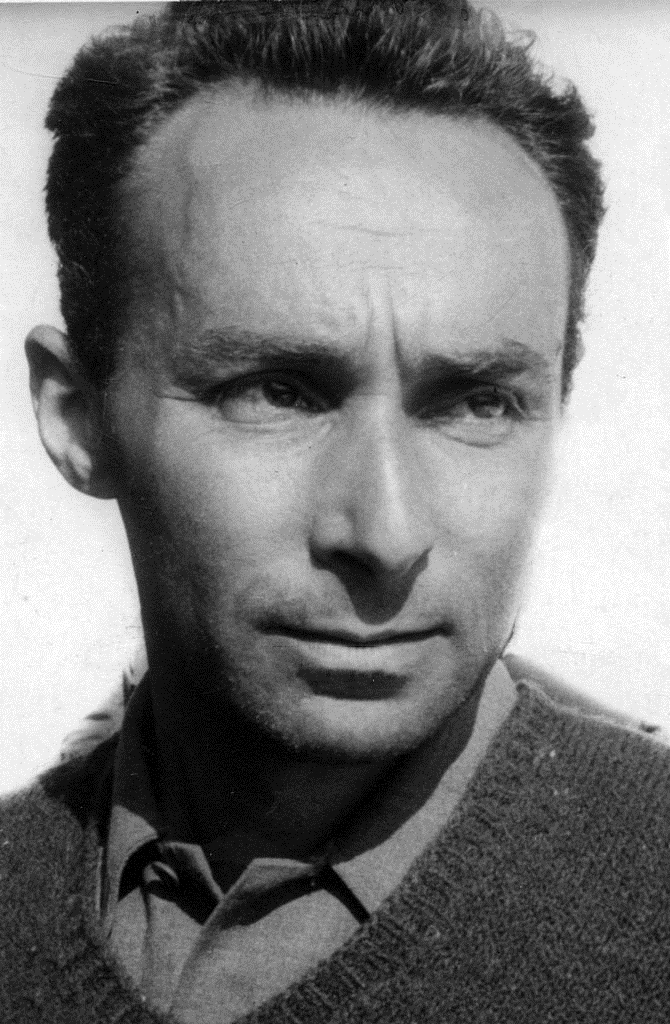

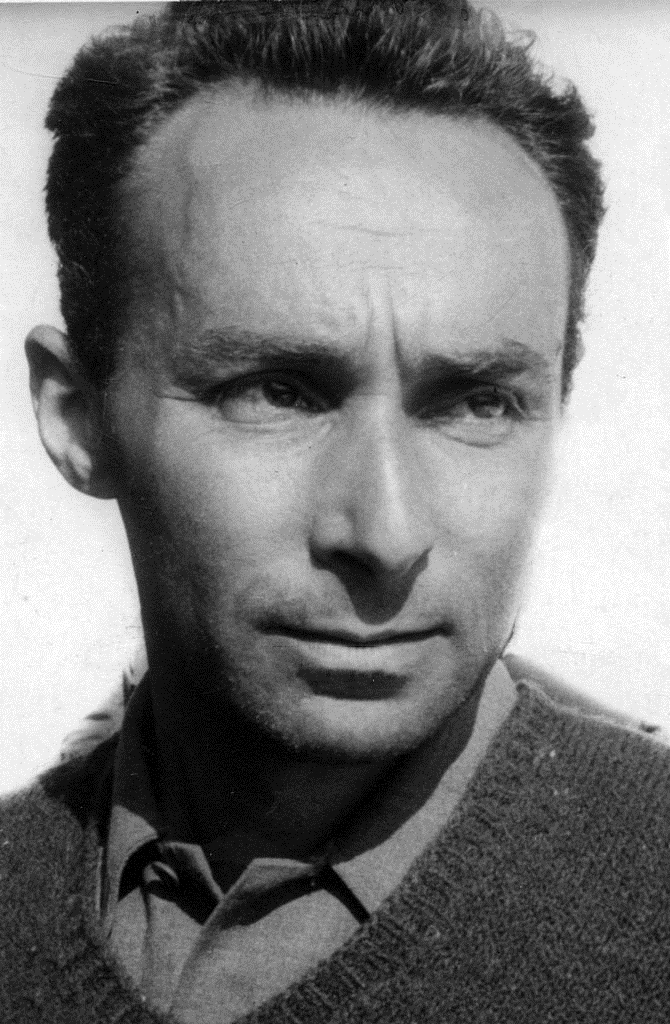

Primo Michele Levi (; 31 July 1919 – 11 April 1987) was an Italian chemist, partisan, writer, and Jewish

In 1921 Anna Maria, Levi's sister, was born; he remained close to her all her life. In 1925 he entered the primary school in Turin. A thin and delicate child, he was shy and considered himself ugly; he excelled academically. His school record includes long periods of absence during which he was tutored at home, at first by Emilia Glauda and then by Marisa Zini, daughter of philosopher Zino Zini. The children spent summers with their mother in the Waldensian valleys southwest of Turin, where Rina rented a farmhouse. His father remained in the city, partly because of his dislike of the rural life, but also because of his infidelities.

In September 1930 Levi entered the Royal Gymnasium a year ahead of normal entrance requirements. In class he was the youngest, the shortest and the cleverest, as well as being the only Jew. Only two boys there bullied him for being Jewish, but their animosity was traumatic. In August 1932, following two years attendance also at the

In 1921 Anna Maria, Levi's sister, was born; he remained close to her all her life. In 1925 he entered the primary school in Turin. A thin and delicate child, he was shy and considered himself ugly; he excelled academically. His school record includes long periods of absence during which he was tutored at home, at first by Emilia Glauda and then by Marisa Zini, daughter of philosopher Zino Zini. The children spent summers with their mother in the Waldensian valleys southwest of Turin, where Rina rented a farmhouse. His father remained in the city, partly because of his dislike of the rural life, but also because of his infidelities.

In September 1930 Levi entered the Royal Gymnasium a year ahead of normal entrance requirements. In class he was the youngest, the shortest and the cleverest, as well as being the only Jew. Only two boys there bullied him for being Jewish, but their animosity was traumatic. In August 1932, following two years attendance also at the

Fossoli was then taken over by the Nazis, who started arranging the deportations of the Jews to eastern concentration and death camps. On the second of these transports, on 21 February 1944, Levi and other inmates were transported in twelve cramped cattle trucks to

Fossoli was then taken over by the Nazis, who started arranging the deportations of the Jews to eastern concentration and death camps. On the second of these transports, on 21 February 1944, Levi and other inmates were transported in twelve cramped cattle trucks to

In March 1985 he wrote the introduction to the re-publication of the autobiography of

In March 1985 he wrote the introduction to the re-publication of the autobiography of

'Primo on the parapet,'

ouTube 2010

Announcement of ''The Complete Works of Primo Levi''

*

International Primo Levi Studies Center

Centro Primo Levi New York

an article in th

TLS

by Clive Sinclair, 11 July 2007

Includes writing by Levi

page by the Operatist who composed in honor of Levi

by Diego Gambetta, Boston Review, Summer 1999 issue. * *

Primo Levi's house

BBC Interview with Primo Levi

Thames Television interview from 1972

{{DEFAULTSORT:Levi, Primo 1919 births 1987 deaths 1987 suicides 20th-century Italian Jews 20th-century Italian novelists 20th-century Italian poets 20th-century Italian politicians 20th-century male writers 20th-century memoirists Action Party (Italy) politicians Auschwitz concentration camp survivors Fossoli camp survivors Italian anti-fascists Italian atheists Italian chemists Italian male novelists Italian male poets Italian male short story writers Italian memoirists Italian science fiction writers Jewish atheists Jewish anti-fascists Jewish chemists Jewish Italian writers Jewish partisans Levites Members of Giustizia e Libertà Modernist writers Scientists from Turin Premio Campiello winners Strega Prize winners Suicides by jumping in Italy University of Turin alumni Viareggio Prize winners

Holocaust survivor

Holocaust survivors are people who survived the Holocaust, defined as the persecution and attempted annihilation of the Jews by Nazi Germany and its allies before and during World War II in Europe and North Africa. There is no universally accep ...

. He was the author of several books, collections of short stories, essays, poems and one novel. His best-known works include ''If This Is a Man

''If This Is a Man'' ( it, Se questo è un uomo ; United States title: ''Survival in Auschwitz'') is a memoir by Italian Jewish writer Primo Levi, first published in 1947. It describes his arrest as a member of the Italian anti-fascist resis ...

'' (1947, published as ''Survival in Auschwitz'' in the United States), his account of the year he spent as a prisoner in the Auschwitz concentration camp

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

in Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

-occupied Poland; and '' The Periodic Table'' (1975), linked to qualities of the elements, which the Royal Institution named the best science book ever written.

Levi died in 1987 from injuries sustained in a fall from a third-story apartment landing. His death was officially ruled a suicide, but some, after careful consideration, have suggested that the fall was accidental because he left no suicide note, there were no witnesses, and he was on medication that could have affected his blood pressure and caused him to fall accidentally.

Biography

Early life

Levi was born in 1919 inTurin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

, Italy, at Corso Re Umberto 75, into a liberal Jewish family. His father, Cesare, worked for the manufacturing firm Ganz

The Ganz Works or Ganz ( or , ''Ganz companies'', formerly ''Ganz and Partner Iron Mill and Machine Factory'') was a group of companies operating between 1845 and 1949 in Budapest, Hungary. It was named after Ábrahám Ganz, the founder and th ...

and spent much of his time working abroad in Hungary, where Ganz was based. Cesare was an avid reader and autodidact. Levi's mother, Ester, known to everyone as Rina, was well educated, having attended the . She too was an avid reader, played the piano, and spoke fluent French.Angier p 50. The marriage between Rina and Cesare had been arranged by Rina's father. On their wedding day, Rina's father, Cesare Luzzati, gave Rina the apartment at , where Primo Levi lived for almost his entire life.

In 1921 Anna Maria, Levi's sister, was born; he remained close to her all her life. In 1925 he entered the primary school in Turin. A thin and delicate child, he was shy and considered himself ugly; he excelled academically. His school record includes long periods of absence during which he was tutored at home, at first by Emilia Glauda and then by Marisa Zini, daughter of philosopher Zino Zini. The children spent summers with their mother in the Waldensian valleys southwest of Turin, where Rina rented a farmhouse. His father remained in the city, partly because of his dislike of the rural life, but also because of his infidelities.

In September 1930 Levi entered the Royal Gymnasium a year ahead of normal entrance requirements. In class he was the youngest, the shortest and the cleverest, as well as being the only Jew. Only two boys there bullied him for being Jewish, but their animosity was traumatic. In August 1932, following two years attendance also at the

In 1921 Anna Maria, Levi's sister, was born; he remained close to her all her life. In 1925 he entered the primary school in Turin. A thin and delicate child, he was shy and considered himself ugly; he excelled academically. His school record includes long periods of absence during which he was tutored at home, at first by Emilia Glauda and then by Marisa Zini, daughter of philosopher Zino Zini. The children spent summers with their mother in the Waldensian valleys southwest of Turin, where Rina rented a farmhouse. His father remained in the city, partly because of his dislike of the rural life, but also because of his infidelities.

In September 1930 Levi entered the Royal Gymnasium a year ahead of normal entrance requirements. In class he was the youngest, the shortest and the cleverest, as well as being the only Jew. Only two boys there bullied him for being Jewish, but their animosity was traumatic. In August 1932, following two years attendance also at the Talmud Torah

Talmud Torah ( he, תלמוד תורה, lit. 'Study of the Torah') schools were created in the Jewish world, both Ashkenazic and Sephardic, as a form of religious school for boys of modest backgrounds, where they were given an elementary educ ...

school in Turin to pick up the elements of doctrine and culture, he sang in the local synagogue for his Bar Mitzvah. In 1933, as was expected of all young Italian schoolboys, he joined the Avanguardisti

Opera Nazionale Balilla (ONB) was an Italian Fascist youth organization functioning between 1926 and 1937, when it was absorbed into the Gioventù Italiana del Littorio (GIL), a youth section of the National Fascist Party.

It takes its name fr ...

movement for young Fascists

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and th ...

. He avoided rifle drill by joining the ski

A ski is a narrow strip of semi-rigid material worn underfoot to glide over snow. Substantially longer than wide and characteristically employed in pairs, skis are attached to ski boots with ski bindings, with either a free, lockable, or partia ...

division, and spent every Saturday during the season on the slopes above Turin. As a young boy Levi was plagued by illness, particularly chest infections, but he was keen to participate in physical activity. In his teens, Levi and a few friends would sneak into a disused sports stadium and conduct athletic competitions.

In July 1934 at the age of 14, he sat the exams for the Liceo Classico D'Azeglio

Liceo Classico Massimo d'Azeglio is a public sixth form college/senior high school (''liceo classico'') in Turin, Italy. It is named after the politician Massimo d'Azeglio.

History

It was established as the Collegio di Porta Nuova in 1831 and be ...

, a Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Generally in that type of school the th ...

(sixth form

In the education systems of England, Northern Ireland, Wales, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and some other Commonwealth countries, sixth form represents the final two years of secondary education, ages 16 to 18. Pupils typically prepare for A-l ...

or senior high school

A secondary school describes an institution that provides secondary education and also usually includes the building where this takes place. Some secondary schools provide both '' lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper seconda ...

) specializing in the classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

, and was admitted that year. The school was noted for its well-known anti-Fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were ...

teachers, among them the philosopher Norberto Bobbio

Norberto Bobbio (; 18 October 1909 – 9 January 2004) was an Italian philosopher of law and political sciences and a historian of political thought. He also wrote regularly for the Turin-based daily ''La Stampa''.

Bobbio was a social libe ...

, and Cesare Pavese, who later became one of Italy's best-known novelists. Levi continued to be bullied during his time at the Lyceum, although six other Jews were in his class. Upon reading ''Concerning the Nature of Things'' by Australian scientist Sir William Bragg

Sir William Henry Bragg (2 July 1862 – 12 March 1942) was an English physicist, chemist, mathematician, and active sportsman who uniquelyThis is still a unique accomplishment, because no other parent-child combination has yet shared a Nobel ...

, Levi decided that he wanted to be a chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

.

In 1937, he was summoned before the War Ministry and accused of ignoring a draft notice from the Italian Royal Navy

The ''Regia Marina'' (; ) was the navy of the Kingdom of Italy (''Regno d'Italia'') from 1861 to 1946. In 1946, with the birth of the Italian Republic (''Repubblica Italiana''), the ''Regia Marina'' changed its name to ''Marina Militare'' ("M ...

—one day before he was to write a final examination on Italy's participation in the Spanish Civil War, based on a quote from Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of "scientifi ...

: "We have the singular merit of being brave to the utmost degree." Distracted and terrified by the draft accusation, he failed the exam—the first poor grade of his life—and was devastated. His father was able to keep him out of the Navy by enrolling him in the Fascist militia (''Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale''). He remained a member through his first year of university, until passage of the Italian Racial Laws of 1938 forced his expulsion. Levi later recounted this series of events in the short story "Fra Diavolo on the Po".

He retook and passed his final examinations, and in October enrolled at the University of Turin

The University of Turin (Italian: ''Università degli Studi di Torino'', UNITO) is a public research university in the city of Turin, in the Piedmont region of Italy. It is one of the oldest universities in Europe and continues to play an impo ...

to study chemistry. As one of 80 candidates, he spent three months taking lectures, and in February, after passing his ''colloquio'' (oral examination), he was selected as one of 20 to move on to the full-time chemistry curriculum.

In the liberal period as well as in the first decade of the Fascist regime, Jews held many public positions, and were prominent in literature, science and politics. In 1929 Mussolini signed an agreement with the Catholic Church, the Lateran Treaty

The Lateran Treaty ( it, Patti Lateranensi; la, Pacta Lateranensia) was one component of the Lateran Pacts of 1929, agreements between the Kingdom of Italy under King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy and the Holy See under Pope Pius XI to settle ...

, which established Catholicism as the State religion, allowed the Church to influence many sectors of education and public life, and relegated other religions to the status of "tolerated cults". In 1936 Italy's conquest of Ethiopia and the expansion of what the regime regarded as the Italian "colonial empire" brought the question of "race" to the forefront. In the context set by these events, and the 1940 alliance with Hitler's Germany, the situation of the Jews of Italy changed radically.

In July 1938 a group of prominent Italian scientists and intellectuals published the "Manifesto of Race

The "Manifesto of Race" ( it, "Manifesto della razza", italics=no), otherwise referred to as the Charter of Race or the Racial Manifesto, was a manifesto which was promulgated by the Council of Ministers on the 14th of July 1938, its promulgation ...

," a mixture of racial and ideological antisemitic theories from ancient and modern sources. This treatise formed the basis for the Italian Racial Laws of October 1938. After its enactment Italian Jews lost their basic civil rights, positions in public offices, and their assets. Their books were prohibited: Jewish writers could no longer publish in magazines owned by Aryans. Jewish students who had begun their course of study were permitted to continue, but new Jewish students were barred from entering university. Levi had matriculated a year earlier than scheduled enabling him to take a degree.

In 1939, Levi discovered his passion for mountain hiking. A friend, Sandro Delmastro, taught him how to hike, and they spent many weekends in the mountains above Turin. Physical exertion, the risk, and the battle with the elements while following Sandro's example enabled him to put out of his mind the nightmare situation precipitating all over Europe as, communing with the sky and earth, he managed to satisfy his desire for liberty realize fully his own strength, and the reasons behind his ardent need grasp the nature of things that had led him to study chemistry, as he later wrote in the chapter "Iron" of ''The Periodic Table'' (1975). In June 1940 Italy declared war as an ally of Germany against Britain and France, and the first Allied air raids on Turin began two days later. Levi's studies continued during the bombardments. The family suffered additional strain as his father became bedridden with bowel cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC), also known as bowel cancer, colon cancer, or rectal cancer, is the development of cancer from the colon or rectum (parts of the large intestine). Signs and symptoms may include blood in the stool, a change in bowel m ...

.

Chemistry

Because of the new racial laws and the increasing intensity of prevalent fascism, Levi had difficulty finding a supervisor for his graduation thesis, which was on the subject ofWalden inversion

Walden inversion is the inversion of a stereogenic center in a chiral molecule in a chemical reaction. Since a molecule can form two enantiomers around a stereogenic center, the Walden inversion converts the configuration of the molecule fro ...

, a study of the asymmetry of the carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent

In chemistry, the valence (US spelling) or valency (British spelling) of an element is the measure of its combining capacity with o ...

atom. Eventually taken on by Dr. Nicolò Dallaporta, he graduated in mid-1941 with full marks and merit, having submitted additional theses on x-ray

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 picometers to 10 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies in the range 30&nb ...

s and electrostatic energy. His degree certificate bore the remark, "of Jewish race". The racial laws prevented Levi from finding a suitable permanent job after graduation.

In December 1941 Levi received an informal job offer from an Italian officer to work as a chemist, under a clandestine identity, at an asbestos

Asbestos () is a naturally occurring fibrous silicate mineral. There are six types, all of which are composed of long and thin fibrous crystals, each fibre being composed of many microscopic "fibrils" that can be released into the atmosphere b ...

mine in San Vittore. The project was to extract nickel from the mine spoil, a challenge he accepted with pleasure. Levi later understood that, if successful, he would be aiding the German war effort, which was suffering nickel shortages in the production of armaments. The job required Levi to work under a false name with false papers. Three months later, in March 1942, his father died. Levi left the mine in June to work in Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city h ...

. Recruited through a fellow student at Turin University, working for the Swiss firm of A Wander Ltd on a project to extract an anti-diabetic from vegetable matter, he took the job in a Swiss company to escape the race laws. It soon became clear that the project had no chance of succeeding, but it was in no one's interest to say so.

In July 1943, King Victor Emmanuel III

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

deposed Mussolini and appointed a new government under Marshal Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino (, ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime ...

, prepared to sign the Armistice of Cassibile with the Allies. When the armistice was made public on 8 September, the Germans occupied northern and central Italy, liberated Mussolini from imprisonment and appointed him as head of the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

, a puppet state in German-occupied northern Italy. Levi returned to Turin to find his mother and sister in refuge in their holiday home 'La Saccarello' in the hills outside the city. The three embarked to Saint-Vincent in the Aosta Valley

, Valdostan or Valdotainian it, Valdostano (man) it, Valdostana (woman)french: Valdôtain (man)french: Valdôtaine (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title = Official languages

, population_blank1 = Italian French

...

, where they could be hidden. Being pursued as Jews, many of whom had already been interned by the authorities, they moved up the hillside to Amay in the , a rebellious area highly suitable for guerilla activities.

The Italian resistance movement

The Italian resistance movement (the ''Resistenza italiana'' and ''la Resistenza'') is an umbrella term for the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social ...

became increasingly active in the German-occupied zone. Levi and some comrades took to the foothills of the Alps, and in October formed a partisan group in the hope of being affiliated to the liberal ''Giustizia e Libertà

Giustizia e Libertà (; en, Justice and Freedom) was an Italian anti-fascist resistance movement, active from 1929 to 1945.James D. Wilkinson (1981). ''The Intellectual Resistance Movement in Europe''. Harvard University Press. p. 224. The mov ...

''. Untrained for such a venture, he and his companions were arrested by the Fascist militia on 13 December 1943. When told he would be shot as an Italian partisan

The Italian resistance movement (the ''Resistenza italiana'' and ''la Resistenza'') is an umbrella term for the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social ...

, Levi confessed to being Jewish. He was sent to the internment camp at Fossoli near Modena

Modena (, , ; egl, label=Emilian language#Dialects, Modenese, Mòdna ; ett, Mutna; la, Mutina) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) on the south side of the Po Valley, in the Province of Modena in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern I ...

. He recalled that as long as Fossoli was under the control of the Italian Social Republic, rather than Nazi Germany, he was not harmed.

Auschwitz

Fossoli was then taken over by the Nazis, who started arranging the deportations of the Jews to eastern concentration and death camps. On the second of these transports, on 21 February 1944, Levi and other inmates were transported in twelve cramped cattle trucks to

Fossoli was then taken over by the Nazis, who started arranging the deportations of the Jews to eastern concentration and death camps. On the second of these transports, on 21 February 1944, Levi and other inmates were transported in twelve cramped cattle trucks to Monowitz

Monowitz (also known as Monowitz-Buna, Buna and Auschwitz III) was a Nazi concentration camp and labor camp (''Arbeitslager'') run by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland from 1942–1945, during World War II and the Holocaust. For most of its exis ...

, one of the three main camps in the Auschwitz concentration camp complex. Levi (record number 174517) spent eleven months there before the camp was liberated by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

on 27 January 1945. Before their arrival, people were sorted according to whether they could work or not. An acquaintance said that it would make no difference, in the end, and declared he was unable to work and was killed immediately. Of the 650 Italian Jews in his transport, Levi was one of twenty who left the camps alive. The average life expectancy of a new entrant at the camp was three to four months.

Levi knew some German from reading German publications on chemistry; he worked to orient quickly to life in the camp without attracting the attention of the privileged inmates. He used bread to pay a more experienced Italian prisoner for German lessons and orientation in Auschwitz. He was given a smuggled soup ration each day by Lorenzo Perrone, an Italian civilian bricklayer working there as a forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

er. Levi's professional qualifications were useful: in mid-November 1944, he secured a position as an assistant in IG Farben

Interessengemeinschaft Farbenindustrie AG (), commonly known as IG Farben (German for 'IG Dyestuffs'), was a German chemical and pharmaceutical conglomerate (company), conglomerate. Formed in 1925 from a merger of six chemical companies—BASF, ...

's Buna Werke laboratory that was intended to produce synthetic rubber

A synthetic rubber is an artificial elastomer. They are polymers synthesized from petroleum byproducts. About 32-million metric tons of rubbers are produced annually in the United States, and of that amount two thirds are synthetic. Synthetic rubbe ...

. By avoiding hard labour in freezing outdoor temperatures he was able to survive; also, by stealing materials from the laboratory and trading them for extra food. Shortly before the camp was liberated by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

, he fell ill with scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as Scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'' a Group A streptococcus (GAS). The infection is a type of Group A streptococcal infection (Group A strep). It most commonly affects childr ...

and was placed in the camp's sanatorium (camp hospital). On 18 January 1945, the SS hurriedly evacuated the camp as the Red Army approached, forcing all but the gravely ill on a long death march

A death march is a forced march of prisoners of war or other captives or deportees in which individuals are left to die along the way. It is distinguished in this way from simple prisoner transport via foot march. Article 19 of the Geneva Convent ...

to a site further from the front, which resulted in the deaths of the vast majority of the remaining prisoners on the march. Levi's illness spared him this fate.

Although liberated on 27 January 1945, Levi did not reach Turin until 19 October 1945. After spending some time in a Soviet camp for former concentration camp inmates, he embarked on an arduous journey home in the company of former Italian prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

who had been part of the Italian Army in Russia

The Italian Army in Russia ( it, Armata Italiana in Russia; ARMIR) was an army-sized unit of the Royal Italian Army which fought on the Eastern Front during World War II between July 1942 and April 1943. The ARMIR was also known as the 8th ...

. His long railway journey home to Turin took him on a circuitous route from Poland, through Belarus, Ukraine, Romania, Hungary, Austria, and Germany - an arduous journey described especially in his 1963 work The Truce

''The Truce'' ( it, La tregua), titled ''The Reawakening'' in the US, is a book by the Italian author Primo Levi. It is the sequel to '' If This Is a Man'' and describes the author's experiences from the liberation of Auschwitz ( Monowitz), whi ...

- noting the millions of displaced people on the roads and trains throughout Europe in that period.

Writing career

1946–1960

Levi was almost unrecognisable on his return to Turin. Malnutritionedema

Edema, also spelled oedema, and also known as fluid retention, dropsy, hydropsy and swelling, is the build-up of fluid in the body's Tissue (biology), tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may include skin which feels t ...

had bloated his face. Sporting a scrawny beard and wearing an old Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

uniform, he returned to Corso Re Umberto. The next few months gave him an opportunity to recover physically, re-establish contact with surviving friends and family, and start looking for work. Levi suffered from the psychological trauma of his experiences. Having been unable to find work in Turin, he started to look for work in Milan. On his train journeys, he began to tell people he met stories about his time at Auschwitz.

At a Jewish New Year party in 1946, he met Lucia Morpurgo, who offered to teach him to dance. Levi fell in love with Lucia. At about this time, he started writing poetry about his experiences in Auschwitz.

On 21 January 1946 he started work at DUCO, a Du Pont Company paint factory outside Turin. Because of the extremely limited train service, Levi stayed in the factory dormitory during the week. This gave him the opportunity to write undisturbed. He started to write the first draft of ''If This Is a Man

''If This Is a Man'' ( it, Se questo è un uomo ; United States title: ''Survival in Auschwitz'') is a memoir by Italian Jewish writer Primo Levi, first published in 1947. It describes his arrest as a member of the Italian anti-fascist resis ...

''. Every day he scribbled notes on train tickets and scraps of paper as memories came to him. At the end of February, he had ten pages detailing the last ten days between the German evacuation and the arrival of the Red Army. For the next ten months, the book took shape in his dormitory as he typed up his recollections each night.

On 22 December 1946, the manuscript was complete. Lucia, who now reciprocated Levi's love, helped him to edit it, to make the narrative flow more naturally. In January 1947, Levi was taking the finished manuscript around to publishers. It was rejected by Einaudi Einaudi is an Italian surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Luigi Einaudi (1874–1961), Italian politician

*Mario Einaudi (1905–1994), Italian political scientist, son of Luigi

*Giulio Einaudi (1912–1999), Italian publisher, son o ...

on the advice of Natalia Ginzburg

Natalia Ginzburg (, ; ; 14 July 1916 – 7 October 1991) was an Italian author whose work explored family relationships, politics during and after the Fascist years and World War II, and philosophy. She wrote novels, short stories and essays, fo ...

, and in the United States was turned down by Little, Brown and Company

Little, Brown and Company is an American publishing company founded in 1837 by Charles Coffin Little and James Brown in Boston. For close to two centuries it has published fiction and nonfiction by American authors. Early lists featured Emily ...

on the advice of rabbi Joshua Liebman

Joshua Loth Liebman (1907–1948) was an American Reform rabbi and best-selling author, best known for the book ''Peace of Mind'', which spent more than a year at #1 on the New York Times Best Seller list.

Biography

Born in Hamilton, Ohio, Lie ...

, an opinion which contributed to the neglect of his work in that country for four decades. The social wounds of the war years were still too fresh, and he had no literary experience to give him a reputation as an author.

Eventually Levi found a publisher, Franco Antonicelli, through a friend of his sister's.Thomson p. 246. Antonicelli was an amateur publisher, but as an active anti-Fascist, he supported the idea of the book.

At the end of June 1947, Levi suddenly left DUCO and teamed up with an old friend Alberto Salmoni to run a chemical consultancy from the top floor of Salmoni's parents' house. Many of Levi's experiences of this time found their way into his later writing. They made most of their money from making and supplying stannous chloride

Tin(II) chloride, also known as stannous chloride, is a white crystalline solid with the formula . It forms a stable dihydrate, but aqueous solutions tend to undergo hydrolysis, particularly if hot. SnCl2 is widely used as a reducing agent (in acid ...

for mirror makers, delivering the unstable chemical by bicycle across the city. The attempts to make lipsticks from reptile excreta and a coloured enamel to coat teeth were turned into short stories. Accidents in their laboratory filled the Salmoni house with unpleasant smells and corrosive gases.

In September 1947, Levi married Lucia and a month later, on 11 October, ''If This Is a Man'' was published with a print run of 2,000 copies. In April 1948, with Lucia pregnant with their first child, Levi decided that the life of an independent chemist was too precarious. He agreed to work for Accatti in the family paint business which traded under the name SIVA. In October 1948, his daughter Lisa was born.

During this period, his friend Lorenzo Perrone's physical and psychological health declined. Lorenzo had been a civilian forced worker in Auschwitz, who for six months had given part of his ration and a piece of bread to Levi without asking for anything in return. The gesture saved Levi's life. In his memoir, Levi contrasted Lorenzo with everyone else in the camp, prisoners and guards alike, as someone who managed to preserve his humanity. After the war, Lorenzo could not cope with the memories of what he had seen, and descended into alcoholism. Levi made several trips to rescue his old friend from the streets, but in 1952 Lorenzo died. In gratitude for his kindness in Auschwitz, Levi named both of his children, Lisa Lorenza and Renzo, after him.

In 1950, having demonstrated his chemical talents to Accatti, Levi was promoted to Technical Director at SIVA. As SIVA's principal chemist and trouble shooter, Levi travelled abroad. He made several trips to Germany and carefully engineered his contacts with senior German businessmen and scientists. Wearing short-sleeved shirts, he made sure they saw his prison camp number tattoo

A tattoo is a form of body modification made by inserting tattoo ink, dyes, and/or pigments, either indelible or temporary, into the dermis layer of the skin to form a design. Tattoo artists create these designs using several Process of tatt ...

ed on his arm.

He became involved in organisations pledged to remembering and recording the horror of the camps. In 1954 he visited Buchenwald

Buchenwald (; literally 'beech forest') was a Nazi concentration camp established on hill near Weimar, Germany, in July 1937. It was one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within Germany's 1937 borders. Many actual or su ...

to mark the ninth anniversary of the camp's liberation from the Nazis. Levi dutifully attended many such anniversary events over the years and recounted his own experiences. In July 1957, his son Renzo was born.

Despite a positive review by Italo Calvino

Italo Calvino (, also , ;. RAI (circa 1970), retrieved 25 October 2012. 15 October 1923 – 19 September 1985) was an Italian writer and journalist. His best known works include the ''Our Ancestors'' trilogy (1952–1959), the '' Cosmicomi ...

in , only 1,500 copies of ''If This Is a Man'' were sold. In 1958 Einaudi Einaudi is an Italian surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Luigi Einaudi (1874–1961), Italian politician

*Mario Einaudi (1905–1994), Italian political scientist, son of Luigi

*Giulio Einaudi (1912–1999), Italian publisher, son o ...

, a major publisher, published it in a revised form and promoted it.

In 1958 Stuart Woolf, in close collaboration with Levi, translated ''If This Is a Man'' into English, and it was published in the UK in 1959 by Orion Press. Also in 1959 Heinz Riedt, also under close supervision by Levi, translated it into German. As one of Levi's primary reasons for writing the book was to get the German people to realise what had been done in their name, and to accept at least partial responsibility, this translation was perhaps the most significant to him.

1961–1974

Levi began writing ''The Truce'' early in 1961; it was published in 1963, almost 16 years after his first book. That year it won the first annualPremio Campiello

The ''Premio Campiello'' is an annual Italian literary prize.

A Jury of Literary Experts (''Giuria di letterati'' in Italian) identifies books published during the year and, in a public hearing, selects five of those as finalists. These books ar ...

literary award. It is often published in one volume with ''If This Is a Man'', as it covers his long return through eastern Europe from Auschwitz. Levi's reputation was growing. He regularly contributed articles to , the Turin newspaper. He worked to gain a reputation as a writer about subjects other than surviving Auschwitz.

In 1963, he suffered his first major bout of depression. At the time he had two young children, and a responsible job at a factory where accidents could and did have terrible consequences. He travelled and became a public figure. But the memory of what happened less than twenty years earlier still burned in his mind. Today the link between such trauma and depression is better understood. Doctors prescribed several different drugs over the years, but these had variable efficacy and side effects.

In 1964 Levi collaborated on a radio play based upon ''If This Is a Man'' with the state broadcaster RAI

RAI – Radiotelevisione italiana (; commercially styled as Rai since 2000; known until 1954 as Radio Audizioni Italiane) is the national public broadcasting company of Italy, owned by the Ministry of Economy and Finance. RAI operates many ter ...

, and in 1966 with a theatre production.

He published two volumes of science fiction short stories under the pen name of Damiano Malabaila, which explored ethical and philosophical questions. These imagined the effects on society of inventions which many would consider beneficial, but which, he saw, would have serious implications. Many of the stories from the two books (''Natural Histories'', 1966) and (''Structural Defect'', 1971) were later collected and published in English as ''The Sixth Day and Other Tales''.

In 1974 Levi arranged to go into semi-retirement from SIVA in order to have more time to write. He also wanted to escape the burden of responsibility for managing the paint plant.

1975–1987

In 1975 a collection of Levi's poetry was published under the title (''The Bremen Beer Hall''). It was published in English as ''Shema: Collected Poems''. He wrote two other highly praised memoirs, (''Moments of Reprieve'', 1978) and (''The Periodic Table'', 1975). ''Moments of Reprieve

''Moments of Reprieve'' is a book of autobiographical character studies/vignettes by Primo Levi.

The book features fifteen character studies of people the author met during his time in the Auschwitz concentration camp. Some of the vignettes featu ...

'' deals with characters he observed during imprisonment. '' The Periodic Table'' is a collection of short pieces, based in episodes from his life but including two short stories that he wrote while employed in 1941 at the asbestos mine in San Vittore. Each story was related in some way to one of the chemical elements. At London's Royal Institution on 19 October 2006, ''The Periodic Table'' was voted onto the shortlist for the best science book ever written.

In 1977 at the age of 58, Levi retired as a part-time consultant at the SIVA paint factory to devote himself full-time to writing. Like all his books, ''La chiave a stella'' (1978), published in the US in 1986 as ''The Monkey Wrench'' and in the UK in 1987 as ''The Wrench,'' is difficult to categorize. Some reviews describe it as a collection of stories about work and workers told by a narrator who resembles Levi. Others have called it a novel, created by the linked stories and characters. Set in a Fiat-run company town in Russia called Togliattigrad, it portrays the engineer as a hero on whom others depend. The underlying philosophy is that pride in one's work is necessary for fulfillment. The engineer Faussone travels the world as an expert in erecting cranes and bridges. Left-wing critics said he did not describe the harsh working conditions on the assembly lines at Fiat. It brought Levi a wider audience in Italy. '' The Wrench'' won the Strega Prize

The Strega Prize ( it, Premio Strega ) is the most prestigious Italian literary award. It has been awarded annually since 1947 for the best work of prose fiction written in the Italian language by an author of any nationality and first published ...

in 1979. Most of the stories involve the solution of industrial problems by the use of troubleshooting

Troubleshooting is a form of problem solving, often applied to repair failed products or processes on a machine or a system. It is a logical, systematic search for the source of a problem in order to solve it, and make the product or process ope ...

skills; many stories come from the author's personal experience.

In 1984 Levi published his only novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itsel ...

, '' If Not Now, When?''— or his second novel, if ''The Monkey Wrench'' is counted. It traces the fortunes of a group of Jewish partisans

Jewish partisans were fighters in irregular military groups participating in the Jewish resistance movement against Nazi Germany and its collaborators during World War II.

A number of Jewish partisan groups operated across Nazi-occupied Euro ...

behind German lines during World War II as they seek to survive and continue their fight against the occupier. With the ultimate goal of reaching Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

to take part in the development of a Jewish national home

A homeland for the Jewish people is an idea rooted in Jewish history, religion, and culture. The Jewish aspiration to return to Zion, generally associated with divine redemption, has suffused Jewish religious thought since the destruction o ...

, the partisan band reaches Poland and then German territory. There the surviving members are officially received as displaced persons

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, g ...

in territory held by the Western allies. Finally, they succeed in reaching Italy, on their way to Palestine. The novel won both the and the .

The book was inspired by events during Levi's train journey home after release from the camp, narrated in ''The Truce''. At one point in the journey, a band of Zionists hitched their wagon to the refugee train. Levi was impressed by their strength, resolve, organisation, and sense of purpose.

Levi became a major literary figure in Italy, and his books were translated into many other languages. ''The Truce'' became a standard text in Italian schools. In 1985, he flew to the United States for a 20-day speaking tour. Although he was accompanied by Lucia, the trip was very draining for him.

In the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

his early works were not accepted by censors as he had portrayed Soviet soldiers as slovenly and disorderly rather than heroic. In Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, a country formed partly by Jewish survivors who lived through horrors similar to those Levi described, many of his works were not translated and published until after his death.

In March 1985 he wrote the introduction to the re-publication of the autobiography of

In March 1985 he wrote the introduction to the re-publication of the autobiography of Rudolf Höss

Rudolf Franz Ferdinand Höss (also Höß, Hoeß, or Hoess; 25 November 1901 – 16 April 1947) was a German SS officer during the Nazi era who, after the defeat of Nazi Germany, was convicted for war crimes. Höss was the longest-serving comm ...

, who was commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp from 1940 to 1943. In it he writes, "It's filled with evil . . . and reading it is agony."

Also in 1985 a volume of his essays, previously published in , was published under the title (''Other People's Trades''). Levi used to write these stories and hoard them, releasing them to at the rate of about one a week. The essays ranged from book reviews and ponderings about strange things in nature, to fictional short stories.

In 1986 his book (''The Drowned and the Saved

''The Drowned and the Saved'' ( it, I sommersi e i salvati) is a book of essays by Italian-Jewish author and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi on life and death in the Nazi extermination camps, drawing on his personal experience as a survivor of Au ...

''), was published. In it he tried to analyse why people behaved the way they did at Auschwitz, and why some survived whilst others perished. In his typical style, he makes no judgments but presents the evidence and asks the questions. For example, one essay examines what he calls "The grey zone", those Jews who did the Germans' dirty work for them and kept the rest of the prisoners in line. He questioned, what made a concert violinist behave as a callous taskmaster?

Also in 1986 another collection of short stories, previously published in , was assembled and published as (some of which were published in the English volume '' The Mirror Maker'').

At the time of his death in April 1987, Levi was working on another selection of essays called ''The Double Bond,'' which took the form of letters to . These essays are very personal in nature. Approximately five or six chapters of this manuscript exist. Carole Angier

Carole Angier (born 30 October 1943) is an English biographer. She was born in London and was raised in Canada before moving back to the UK in her early twenties. She spent many years as a teacher, including periods at the Open University and Birk ...

, in her biography of Levi, describes how she tracked some of these essays down. She wrote that others were being kept from public view by Levi's close friends, to whom he gave them, and they may have been destroyed.

In March 2007 ''Harper's Magazine'' published an English translation of Levi's story , about a fictitious weapon that is fatal at close range but harmless more than a meter away. It originally appeared in his 1971 book , but was published in English for the first time by ''Harper's''.

''A Tranquil Star'', a collection of seventeen stories translated into English by Ann Goldstein and Alessandra Bastagli was published in April 2007.

In 2015, Penguin published ''The Complete Works of Primo Levi'', ed. Ann Goldstein. This is the first time that Levi's entire oeuvre has been translated into English.

Death

Levi died on 11 April 1987 after a fall from the interior landing of his third-story apartment in Turin to the ground floor below. The coroner ruled his death a suicide. Three of his biographers (Angier, Thomson and Anissimov) agreed, but other writers (including at least one who knew him personally) questioned that determination. In his later life, Levi indicated that he was suffering from depression; factors likely included responsibility for his elderly mother and mother-in-law, with whom he was living, and lingering traumatic memories of his experiences. According to the chief rabbi of RomeElio Toaff

Elio Toaff (30 April 1915 – 19 April 2015) was the Chief Rabbi of Rome from 1951 to 2002. He served as a rabbi in Venice from 1947, and in 1951 became the Chief Rabbi of Rome.

Early life

Toaff was born in Livorno in 1915, the son of the city ...

, Levi telephoned him for the first time ten minutes before the incident. Levi said he found it impossible to look at his mother, who was ill with cancer, without recalling the faces of people stretched out on benches in Auschwitz. The Nobel laureate and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel

Elie Wiesel (, born Eliezer Wiesel ''Eliezer Vizel''; September 30, 1928 – July 2, 2016) was a Romanian-born American writer, professor, political activist, Nobel Peace Prize, Nobel laureate, and Holocaust survivor. He authored Elie Wiesel b ...

said, at the time, "Primo Levi died at Auschwitz forty years later."

Several of Levi's friends and associates have argued otherwise. The Oxford sociologist Diego Gambetta

Diego Gambetta (; born 1952) is an Italian-born social scientist. He is a professor of social theory at the European University Institute in Florence, a Carlo Alberto Chair at the Collegio Carlo Alberto in Turin, and an official fellow at Nuff ...

noted that Levi left no suicide note, nor any other indication that he was considering suicide. Documents and testimony suggested that he had plans for both the short- and longer-term at the time. In the days before his death, he had complained to his physician of dizziness due to an operation he had undergone some three weeks earlier. After visiting the apartment complex, Gambetta suggested that Levi lost his balance and fell accidentally. The Nobel laureate Rita Levi-Montalcini

Rita Levi-Montalcini (, ; 22 April 1909 – 30 December 2012) was an Italian Nobel laureate, honored for her work in neurobiology. She was awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine jointly with colleague Stanley Cohen for th ...

, a close friend of Levi, agreed. "As a chemical engineer," she said, "he might have chosen a better way f exiting the worldthan jumping into a narrow stairwell with the risk of remaining paralyzed."

Views on Nazism, Soviet Union and antisemitism

Levi wrote ''If This Is a Man'' to bear witness to the horrors of the Nazis' attempt to exterminate the Jewish people and others. In turn, he read many accounts by witnesses and survivors, and attended meetings of survivors, becoming a prominent symbolic figure for anti-fascists in Italy. Levi visited over 130 schools to talk about his experiences in Auschwitz. He vigorously repudiated revisionist attitudes in German historiography that emerged in theHistorikerstreit

The ''Historikerstreit'' (, "historians' dispute") was a dispute in the late 1980s in West Germany between conservative and left-of-center academics and other intellectuals about how to incorporate Nazi Germany and the Holocaust into German hist ...

led by the works of people like Andreas Hillgruber

Andreas Fritz Hillgruber (18 January 1925 – 8 May 1989) was a conservative German historian who was influential as a military and diplomatic historian who played a leading role in the ''Historikerstreit'' of the 1980s. In his controversial book ...

and Ernst Nolte

Ernst Nolte (11 January 1923 – 18 August 2016) was a German historian and philosopher. Nolte's major interest was the comparative studies of fascism and communism (cf. Comparison of Nazism and Stalinism). Originally trained in philosophy, he was ...

, who drew parallels between Nazism and Stalinism. Levi rejected the idea that the labor camp system depicted in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repress ...

's ''The Gulag Archipelago

''The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation'' (russian: Архипелаг ГУЛАГ, ''Arkhipelag GULAG'') is a three-volume non-fiction text written between 1958 and 1968 by Russian writer and Soviet dissident Aleksandr So ...

'' and that of the Nazi (german: link=no, konzentrationslager; see Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as concen ...

) were comparable. The death rate in Stalin's gulags was 30% at worst, he wrote, while in the extermination camps he estimated it to be 90–98%.

His view was that the Nazi death camps and the attempted annihilation of the Jews was a horror unique in history because the goal was the complete destruction of a race by one that saw itself as superior. He noted that it was highly organized and mechanized; it entailed the degradation of Jews to the point of using their ashes as materials for paths.

Distinct purpose of extermination camps

The purpose of the Nazi camps was not the same as that of Stalin's ''gulags'', Levi wrote in an appendix to ''If This Is a Man'', though it is a "lugubrious comparison between two models of hell." The goal of the was the extermination of the Jewish race in Europe. No one was excluded. No one could renounce Judaism; the Nazis treated Jews as a racial group rather than as a religious one. Levi, along with most of Turin's Jewish intellectuals, had not been religiously observant beforeWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, but the Italian racial laws and the Nazi camps impressed on him his identity as a Jew. Of the many children deported to the camps, almost all were murdered.

Levi wrote in clear, dispassionate style about his experiences in Auschwitz, with an embrace of whatever humanity he found, showing no lasting hatred of the Germans, although he made it clear that he did not forgive any of the culprits.

Works

Adaptations

* Five of Levi's poems (''Shema'', ''25 Febbraio 1944'', ''Il canto del corvo'', ''Cantare'' and ''Congedo'') have been set to music bySimon Sargon

Simon Sargon (6 April 1938 Bombay, India - 25 December 2022 Kensington, Maryland) was an American composer, pianist, and music educator of Israeli and Indian descent. He studied at Brandeis University and at the Juilliard School under Sergius Ka ...

in the song cycle

A song cycle (german: Liederkreis or Liederzyklus) is a group, or cycle (music), cycle, of individually complete Art song, songs designed to be performed in a sequence as a unit.Susan Youens, ''Grove online''

The songs are either for solo voice ...

''Shema: 5 Poems of Primo Levi'' in 1987. In 2021 the work was performed by Megan Marie Hart

Megan Marie Hart (born 1983) is an American operatic soprano from Eugene, Oregon, performing in leading operatic roles and concerts in America and Europe.

Education

Hart was born in Santa Monica, California, and grew up in Eugene, Oregon, af ...

during the opening event of the festival year ' commemorating the first documented mention of Jewish communities in the territory of present-day Germany.

* The 1997 film (''The Truce

''The Truce'' ( it, La tregua), titled ''The Reawakening'' in the US, is a book by the Italian author Primo Levi. It is the sequel to '' If This Is a Man'' and describes the author's experiences from the liberation of Auschwitz ( Monowitz), whi ...

''), starring John Turturro

John Michael Turturro (; born February 28, 1957) is an American actor and filmmaker. He is known for his contributions to the independent film movement. He has appeared in over sixty feature films and has worked frequently with the Coen brothers, ...

, was adapted from his 1963 memoir of the same title and recounts Levi's long journey home with other displaced people after his liberation from Auschwitz.

* ''If This Is a Man

''If This Is a Man'' ( it, Se questo è un uomo ; United States title: ''Survival in Auschwitz'') is a memoir by Italian Jewish writer Primo Levi, first published in 1947. It describes his arrest as a member of the Italian anti-fascist resis ...

'' was adapted by Antony Sher

Sir Antony Sher (14 June 1949 – 2 December 2021) was a British actor, writer and theatre director of South African origin. A two-time Laurence Olivier Award winner and a four-time nominee, he joined the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1982 a ...

into a one-man stage production '' Primo'' in 2004. A version of this production was broadcast on BBC Four

BBC Four is a British free-to-air public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It was launched on 2 March 2002

in the UK on 20 September 2007.

In popular culture

* ''Till My Tale is Told: Women's Memoirs of the Gulag'' (1999), uses a part of the quatrain by Coleridge quoted by Levi in ''The Drowned and the Saved'' as its title. *Christopher Hitchens

Christopher Eric Hitchens (13 April 1949 – 15 December 2011) was a British-American author and journalist who wrote or edited over 30 books (including five essay collections) on culture, politics, and literature. Born and educated in England, ...

' book '' The Portable Atheist'', a collection of extracts of atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

texts, is dedicated to the memory of Levi, "who had the moral fortitude to refuse false consolation even while enduring the 'selection' process in Auschwitz". The dedication quotes Levi in ''The Drowned and the Saved

''The Drowned and the Saved'' ( it, I sommersi e i salvati) is a book of essays by Italian-Jewish author and Holocaust survivor Primo Levi on life and death in the Nazi extermination camps, drawing on his personal experience as a survivor of Au ...

'', asserting, "I too entered the Lager as a nonbeliever, and as a nonbeliever I was liberated and have lived to this day."

* The Primo Levi Center, a non-profit organisation dedicated to studying the history and culture of Italian Jewry, was named after the author and established in New York City in 2003.

* A quotation from Levi appears on the sleeve of the second album by the Welsh rock band Manic Street Preachers

Manic Street Preachers, also known simply as the Manics, are a Welsh Rock music, rock band formed in Blackwood, Caerphilly, Blackwood in 1986. The band consists of cousins James Dean Bradfield (lead vocals, lead guitar) and Sean Moore (musician ...

, titled ''Gold Against the Soul

''Gold Against the Soul'' is the second studio album by Welsh alternative rock band Manic Street Preachers. It was released on 21 June 1993 by record label Columbia.

Noted for its lyrics reflecting melancholia, ''Gold Against the Soul'' integr ...

''. The quote is from Levi's poem "Song of Those Who Died in Vain".

* David Blaine

David Blaine (born April 4, 1973) is an American illusionist, endurance artist, and extreme performer. He is best known for his high-profile feats of endurance and has set and broken several world records.

Early life

Blaine was born and r ...

has Primo Levi's Auschwitz camp number, 174517, tattooed on his left forearm.

* In Lavie Tidhar

Lavie Tidhar ( he, לביא תדהר; born 16 November 1976) is an Israeli-born writer, working across multiple genres. He has lived in the United Kingdom and South Africa for long periods of time, as well as Laos and Vanuatu. As of 2013, Tid ...

's 2014 novel ''A Man Lies Dreaming'', the protagonist Shomer (a Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

pulp writer) encounters Levi in Auschwitz, and is witness to a conversation between Levi and the author Ka-Tzetnik on the subject of writing the Holocaust.

*In the pilot episode of ''Black Earth Rising

''Black Earth Rising'' is a 2018 British television miniseries written and directed by Hugo Blick, about the prosecution of international war criminals. The series is a co-production between BBC Two and Netflix. The show aired on BBC Two in th ...

'', Rwandan genocide survivor and self-described "major depressive" Kate Ashby tells her therapist, in her final session addressing her survivors' guilt and having overmedicated herself with antidepressants, that she has read the Primo Levi book he'd assigned her, and if she chooses to attempt suicide, she'll jump straight out of a third story window.

*The last track on ''The Noise

''the Noise'' was a monthly newspaper serving the cities of Flagstaff, Prescott, Sedona, Cottonwood, Jerome, Clarkdale, and Winslow in northern Arizona. Founded in 1993 by four high school seniors whose rural hometown's budget cuts lead t ...

'' by Peter Hammill

Peter Joseph Andrew Hammill (born 5 November 1948) is an English musician and recording artist. He was a founder member of the progressive rock band Van der Graaf Generator. Best known as a singer/songwriter, he also plays guitar and piano and ...

is entitled "Primo on the Parapet".Peter Hammill

Peter Joseph Andrew Hammill (born 5 November 1948) is an English musician and recording artist. He was a founder member of the progressive rock band Van der Graaf Generator. Best known as a singer/songwriter, he also plays guitar and piano and ...

'Primo on the parapet,'

ouTube 2010

References

Notes Bibliography * * * * * Further reading * Giffuni, Cathe. "An English Bibliography of the Writings of Primo Levi," ''Bulletin of Bibliography'', Vol. 50 No. 3 September 1993, pp. 213–221.External links

Announcement of ''The Complete Works of Primo Levi''

*

International Primo Levi Studies Center

Centro Primo Levi New York

an article in th

TLS

by Clive Sinclair, 11 July 2007

Includes writing by Levi

page by the Operatist who composed in honor of Levi

by Diego Gambetta, Boston Review, Summer 1999 issue. * *

Primo Levi's house

BBC Interview with Primo Levi

Thames Television interview from 1972

{{DEFAULTSORT:Levi, Primo 1919 births 1987 deaths 1987 suicides 20th-century Italian Jews 20th-century Italian novelists 20th-century Italian poets 20th-century Italian politicians 20th-century male writers 20th-century memoirists Action Party (Italy) politicians Auschwitz concentration camp survivors Fossoli camp survivors Italian anti-fascists Italian atheists Italian chemists Italian male novelists Italian male poets Italian male short story writers Italian memoirists Italian science fiction writers Jewish atheists Jewish anti-fascists Jewish chemists Jewish Italian writers Jewish partisans Levites Members of Giustizia e Libertà Modernist writers Scientists from Turin Premio Campiello winners Strega Prize winners Suicides by jumping in Italy University of Turin alumni Viareggio Prize winners