Prime minister of Italy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The prime minister of Italy, officially the president of the Council of Ministers (), is the

As the president of the

As the president of the

In 1892, Giovanni Giolitti, a leftist lawyer and politician, was appointed prime minister by King Umberto I, but after less than a year he was forced to resign and Crispi returned to power. In 1903, he was appointed again head of the government after a period of instability. Giolitti was prime minister five times between 1892 and 1921 and the second-longest serving prime minister in Italian history.

Giolitti was a master in the political art of '' trasformismo'', the method of making a flexible, fluid centrist coalition in Parliament which sought to isolate the extremes of the left and the

In 1892, Giovanni Giolitti, a leftist lawyer and politician, was appointed prime minister by King Umberto I, but after less than a year he was forced to resign and Crispi returned to power. In 1903, he was appointed again head of the government after a period of instability. Giolitti was prime minister five times between 1892 and 1921 and the second-longest serving prime minister in Italian history.

Giolitti was a master in the political art of '' trasformismo'', the method of making a flexible, fluid centrist coalition in Parliament which sought to isolate the extremes of the left and the

The Cambridge companion to modern Italian culture

', p. 44Killinger,

The history of Italy

', p. 127–28 A left-wing liberal with strong ethical concerns, Giolitti's periods in the office were notable for the passage of a wide range of progressive social reforms which improved the living standards of ordinary Italians, together with the enactment of several policies of government intervention.Sarti,

Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present

', pp. 46–48 Besides putting in place several

The Italian prime minister presided over a very unstable political system as in its first sixty years of existence (1861–1921) Italy changed its head of the government 37 times.

Regarding this situation, the first goal of

The Italian prime minister presided over a very unstable political system as in its first sixty years of existence (1861–1921) Italy changed its head of the government 37 times.

Regarding this situation, the first goal of

In the first years of the Republic, the governments were led by De Gasperi, who is also considered a founding father of the

In the first years of the Republic, the governments were led by De Gasperi, who is also considered a founding father of the

In the midst of the ''mani pulite'' operation which shook political parties in 1994, media magnate

In the midst of the ''mani pulite'' operation which shook political parties in 1994, media magnate  After the 2019 European Parliament election in Italy, where the League exceeded Five Star Movement, Matteo Salvini (leader of the League) proposed a no-confidence vote in Conte. Conte resigned, but after the consultations between the President

After the 2019 European Parliament election in Italy, where the League exceeded Five Star Movement, Matteo Salvini (leader of the League) proposed a no-confidence vote in Conte. Conte resigned, but after the consultations between the President

Website of the Prime Minister of Italy

* {{Authority control Politics of Italy 1861 establishments in Italy Articles which contain graphical timelines la:Praeses consilii ministrorum

head of government

In the Executive (government), executive branch, the head of government is the highest or the second-highest official of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presid ...

of the Italian Republic. The office of president of the Council of Ministers is established by articles 92–96 of the Constitution of Italy

The Constitution of the Italian Republic () was ratified on 22 December 1947 by the Constituent Assembly of Italy, Constituent Assembly, with 453 votes in favour and 62 against, before coming into force on 1 January 1948, one century after the p ...

; the president of the Council of Ministers is appointed by the president of the Republic and must have the confidence of the Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

to stay in office.

Prior to the establishment of the Italian Republic, the position was called President of the Council of Ministers of the Kingdom of Italy (''Presidente del Consiglio dei ministri del Regno d'Italia''). From 1925 to 1943 during the Fascist regime, the position was transformed into the dictatorial position of Head of the Government, Prime Minister, Secretary of State (''Capo del Governo, Primo Ministro, Segretario di Stato'') held by Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

, Duce of Fascism, who officially governed on the behalf of the king of Italy

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a constitutional monarch if his power is restrained by ...

. King Victor Emmanuel III removed Mussolini from office in 1943 and the position was restored with Marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used fo ...

Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino ( , ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regim ...

becoming prime minister in 1943, although the original denomination of President of the Council was only restored in 1944, when Ivanoe Bonomi was appointed to the post of prime minister. Alcide De Gasperi became the first prime minister of the Italian Republic in 1946.

The prime minister is the president of the Council of Ministers

Council of Ministers is a traditional name given to the supreme Executive (government), executive organ in some governments. It is usually equivalent to the term Cabinet (government), cabinet. The term Council of State is a similar name that also m ...

which holds executive power and the position is similar to those in most other parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentary democracy, is a form of government where the head of government (chief executive) derives their Election, democratic legitimacy from their ability to command the support ("confidence") of a majority of t ...

s. The formal Italian order of precedence lists the office as being, ceremonially, the fourth-highest Italian state office after the president and the presiding officers of the two houses of parliament. In practice, the prime minister is the country's political leader and ''de facto'' chief executive.

Giorgia Meloni has been the incumbent prime minister since 22 October 2022.

Functions

As the president of the

As the president of the Council of Ministers

Council of Ministers is a traditional name given to the supreme Executive (government), executive organ in some governments. It is usually equivalent to the term Cabinet (government), cabinet. The term Council of State is a similar name that also m ...

, the prime minister is required by the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

to have the supreme confidence of the majority of the voting members of the Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

.

In addition to powers inherent in being a member of the Cabinet, the prime minister holds specific powers, most notably being able to nominate a list of Cabinet ministers to be appointed by the president of the Republic and the countersigning of all legislative instruments having the force of law that are signed by the president of the Republic.

Article 95 of the Italian constitution provides that the prime minister "directs and coordinates the activity of the ministers". This power has been used to a quite variable extent in the history of the Italian state as it is strongly influenced by the political strength of individual ministers and thus by the parties they represent.

The prime minister's activity has often consisted of mediating between the various parties in the majority coalition, rather than directing the activity of the Council of Ministers. The prime minister's supervisory power is further limited by the lack of any formal authority to fire ministers. In the past, in order to make a cabinet reshuffle, prime ministers have sometimes resigned so that they could be re-appointed by the president and allowed to form a new cabinet with new ministers. In order to do this the prime minister needs the support of the president, who could theoretically refuse to re-appoint them following their resignation.

History

The office was first established in 1848 in Italy's predecessor state, the Kingdom of Sardinia—although it was not mentioned in its constitution, the Albertine Statute.Historical Right and Historical Left

After theunification of Italy

The unification of Italy ( ), also known as the Risorgimento (; ), was the 19th century Political movement, political and social movement that in 1861 ended in the Proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, annexation of List of historic states of ...

and the establishment of the kingdom, the procedure did not change. In fact, the candidate for office was appointed by the king

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

and presided over a very unstable political system. The first prime minister was Camillo Benso di Cavour, who was appointed on 23 March 1861, but he died on 6 June the same year. From 1861 to 1911, Historical Right and Historical Left prime ministers alternatively governed the country.

According to the letter of the Statuto Albertino, the prime minister and other ministers were politically responsible to the king and legally responsible to Parliament. With time, it became all but impossible for a king to appoint a government entirely of his own choosing or keep it in office against the will of Parliament. As a result, in practice the prime minister was now both politically and legally responsible to Parliament, and had to maintain its confidence to stay in office.

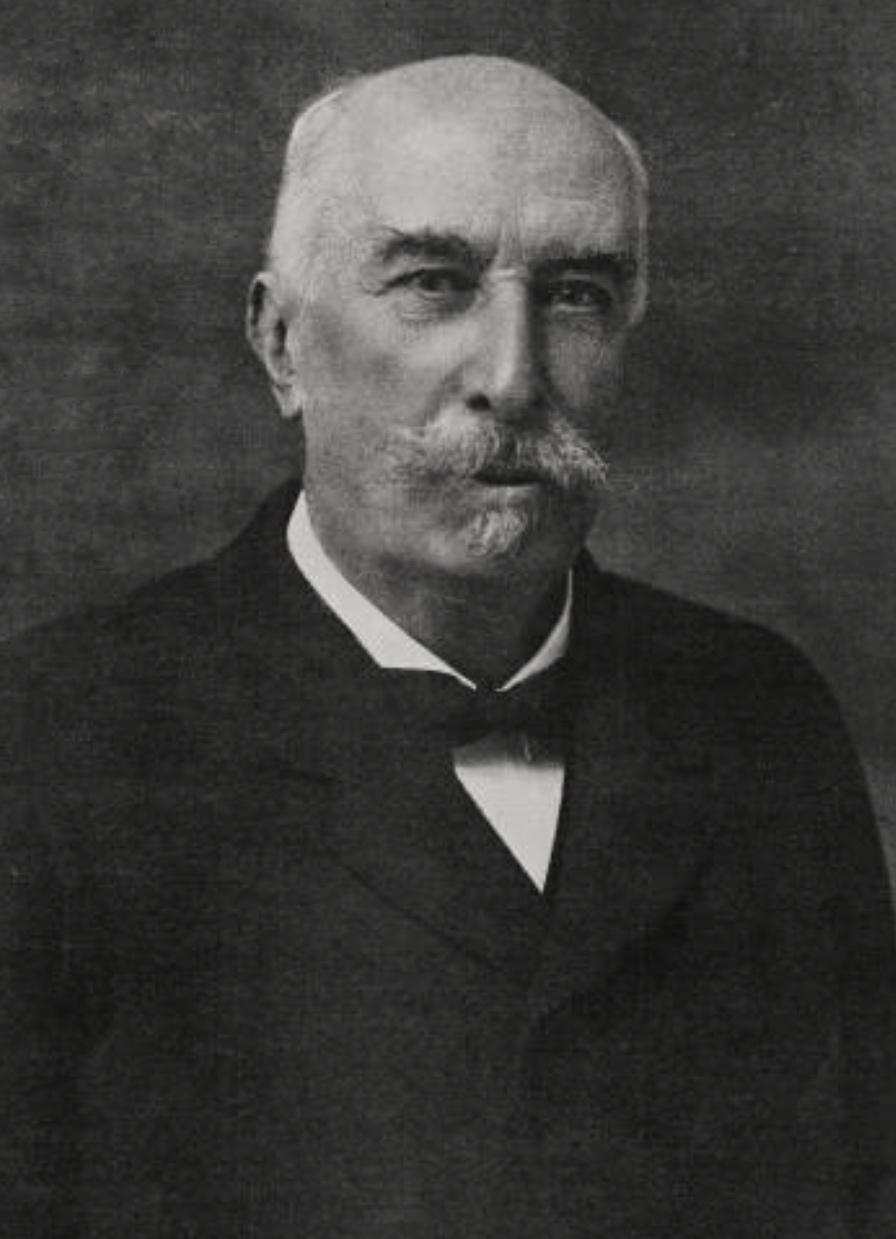

One of the most famous and influential prime ministers of this period was Francesco Crispi, a left-wing patriot and statesman, the first head of the government from Southern Italy. He led the country for six years from 1887 until 1891 and again from 1893 until 1896. Crispi was internationally famous and often mentioned along with world statesmen such as Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

, William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

and Salisbury

Salisbury ( , ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers River Avon, Hampshire, Avon, River Nadder, Nadder and River Bourne, Wi ...

.

Originally an enlightened Italian patriot and democrat liberal, Crispi went on to become a bellicose authoritarian prime minister, ally and admirer of Bismarck. His career ended amid controversy and failure due to becoming involved in a major banking scandal and subsequently fell from power in 1896 after a devastating colonial defeat in Ethiopia. He is often seen as a precursor of the fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

dictator Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

.

Giolittian Era

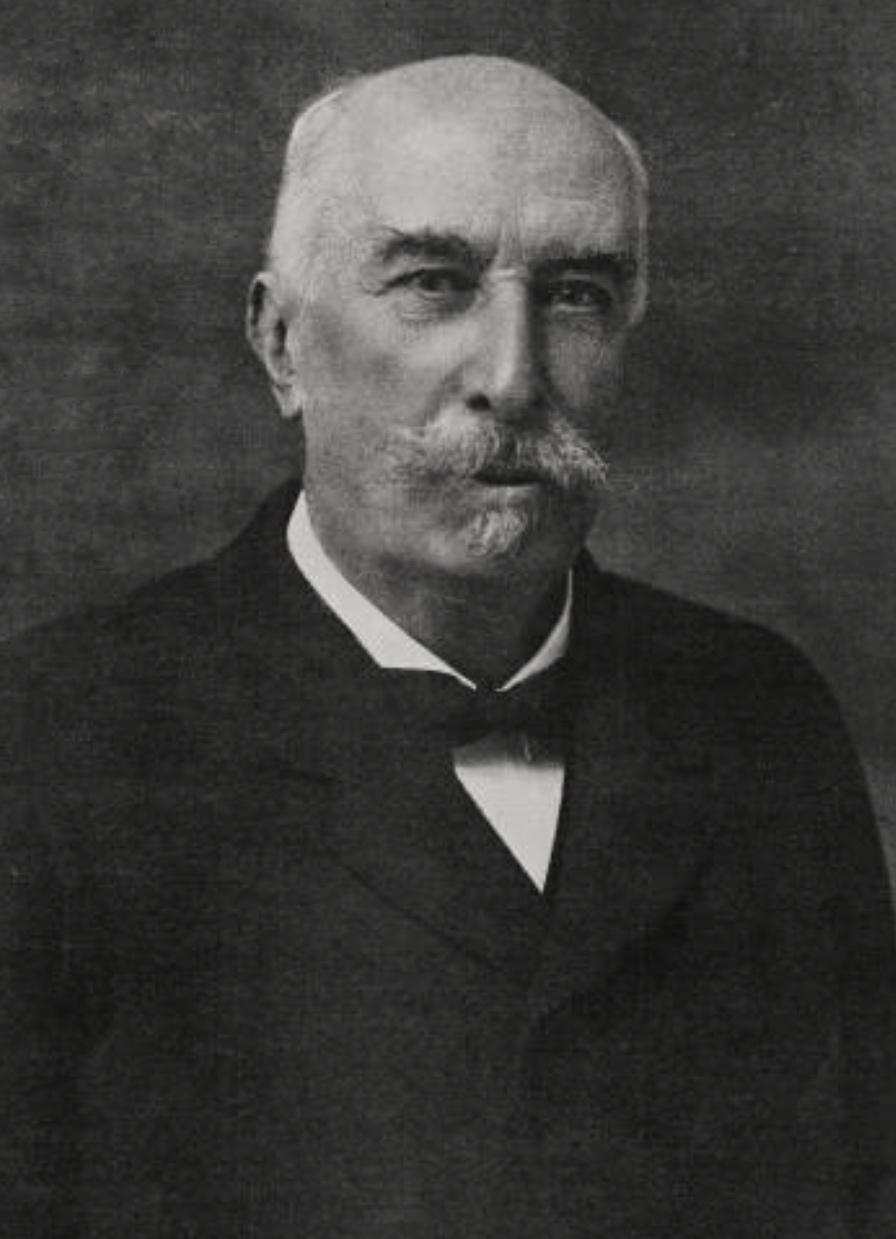

In 1892, Giovanni Giolitti, a leftist lawyer and politician, was appointed prime minister by King Umberto I, but after less than a year he was forced to resign and Crispi returned to power. In 1903, he was appointed again head of the government after a period of instability. Giolitti was prime minister five times between 1892 and 1921 and the second-longest serving prime minister in Italian history.

Giolitti was a master in the political art of '' trasformismo'', the method of making a flexible, fluid centrist coalition in Parliament which sought to isolate the extremes of the left and the

In 1892, Giovanni Giolitti, a leftist lawyer and politician, was appointed prime minister by King Umberto I, but after less than a year he was forced to resign and Crispi returned to power. In 1903, he was appointed again head of the government after a period of instability. Giolitti was prime minister five times between 1892 and 1921 and the second-longest serving prime minister in Italian history.

Giolitti was a master in the political art of '' trasformismo'', the method of making a flexible, fluid centrist coalition in Parliament which sought to isolate the extremes of the left and the right

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of freedom or Entitlement (fair division), entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal sy ...

in Italian politics. Under his influence, the Italian Liberals did not develop as a structured party. They were instead a series of informal personal groupings with no formal links to political constituencies.

The period between the start of the 20th century and the start of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, when he was prime minister and Minister of the Interior from 1901 to 1914 with only brief interruptions, is often called the Giolittian Era.Barański & West, The Cambridge companion to modern Italian culture

', p. 44Killinger,

The history of Italy

', p. 127–28 A left-wing liberal with strong ethical concerns, Giolitti's periods in the office were notable for the passage of a wide range of progressive social reforms which improved the living standards of ordinary Italians, together with the enactment of several policies of government intervention.Sarti,

Italy: a reference guide from the Renaissance to the present

', pp. 46–48 Besides putting in place several

tariff

A tariff or import tax is a duty (tax), duty imposed by a national Government, government, customs territory, or supranational union on imports of goods and is paid by the importer. Exceptionally, an export tax may be levied on exports of goods ...

s, subsidies and government projects, Giolitti also nationalized the private telephone and railroad operators. Liberal proponents of free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

criticized the "Giolittian System", although Giolitti himself saw the development of the national economy as essential in the production of wealth.

Fascist regime

The Italian prime minister presided over a very unstable political system as in its first sixty years of existence (1861–1921) Italy changed its head of the government 37 times.

Regarding this situation, the first goal of

The Italian prime minister presided over a very unstable political system as in its first sixty years of existence (1861–1921) Italy changed its head of the government 37 times.

Regarding this situation, the first goal of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

, appointed in 1922, was to abolish the Parliament's ability to put him to a vote of no confidence

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fi ...

, basing his power on the will of the King and the National Fascist Party alone. After destroying all political opposition through his secret police and outlawing labor strikes,Haugen, pp. 9, 71. Mussolini and his Fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

followers consolidated their power through a series of laws that transformed the nation into a one-party dictatorship. Within five years, he had established dictatorial authority by both legal and extraordinary means, aspiring to create a totalitarian state. In 1925 the title of "President of the Council of Ministers" was changed into "Head of the Government, Prime Minister Secretary of State", symbolizing the new dictatorial powers of Mussolini. The convention that the prime minister was responsible to Parliament had become so entrenched that Mussolini had to pass a law stating that he was not responsible to Parliament.

Mussolini remained in power until he was deposed by King Victor Emmanuel III in 1943 following a vote of no confidence by the Grand Council of Fascism and replaced by General Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino ( , ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regim ...

. A few months later, Italy was invaded by Nazi Germany and Mussolini was reinstated as head of a puppet State called Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic (, ; RSI; , ), known prior to December 1943 as the National Republican State of Italy (; SNRI), but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò (, ), was a List of World War II puppet states#Germany, German puppe ...

, while the authorities of the Kingdom were forced to relocate in Southern Italy, which was under the control of the Allied Forces.

In 1944 Badoglio resigned and Ivanoe Bonomi was appointed to the post of prime minister, restoring the old title of "President of the Council of Ministers. Bonomi was briefly succeeded by Ferruccio Parri in 1945 and then by Alcide de Gasperi, leader of the newly formed Christian Democracy

Christian democracy is an ideology inspired by Christian social teaching to respond to the challenges of contemporary society and politics.

Christian democracy has drawn mainly from Catholic social teaching and neo-scholasticism, as well ...

(''Democrazia Cristiana'', DC) political party.

First decades of the Italian Republic

Following the 1946 Italian institutional referendum, the monarchy was abolished and De Gasperi became the first Prime Minister of the Italian Republic. The First Republic was dominated by the Christian Democracy which was the senior party in each government coalitions from 1946 to 1994 while the opposition was led by the Italian Communist Party (PCI), the largest one in Western Europe. In the first years of the Republic, the governments were led by De Gasperi, who is also considered a founding father of the

In the first years of the Republic, the governments were led by De Gasperi, who is also considered a founding father of the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are Geography of the European Union, located primarily in Europe. The u ...

.

After the death of De Gasperi, Italy returned in a period of political instability and a lot of cabinets were formed in few decades. The second part of the 20th century was dominated by De Gasperi's protégé Giulio Andreotti, who was appointed prime minister seven times from 1972 to 1992.

From the late 1960s until the early 1980s, the country experienced the Years of Lead, a period characterised by economic crisis (especially after the 1973 oil crisis

In October 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) announced that it was implementing a total oil embargo against countries that had supported Israel at any point during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, which began after Eg ...

), widespread social conflicts and terrorist massacres carried out by opposing extremist groups, with the alleged involvement of United States and Soviet intelligence. The Years of Lead culminated in the assassination of the Christian Democrat leader Aldo Moro

Aldo Moro (; 23 September 1916 – 9 May 1978) was an Italian statesman and prominent member of Christian Democracy (Italy), Christian Democracy (DC) and its centre-left wing. He served as prime minister of Italy in five terms from December 1963 ...

in 1978 and the Bologna railway station massacre in 1980, where 85 people died.

In the 1980s, for the first time since 1945 two governments were led by non-Christian Democrat prime ministers: one Republican ( Giovanni Spadolini) and one Socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

( Bettino Craxi). However, the Christian Democrats remained the main government party. During Craxi's government, the economy recovered and Italy became the world's fifth-largest industrial nation, gaining entry into the Group of Seven

The Group of Seven (G7) is an Intergovernmentalism, intergovernmental political and economic forum consisting of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States; additionally, the European Union (EU) is a "non- ...

, but as a result of his spending policies, the Italian national debt skyrocketed during the Craxi era, soon passing 100% of the GDP.

In the early 1990s, Italy faced significant challenges as voters—disenchanted with political paralysis, massive public debt and the extensive corruption system (known as '' Tangentopoli'') uncovered by the " Clean Hands" (''mani pulite'') investigation—demanded radical reforms. The scandals involved all major parties, but especially those in the government coalition: the Christian Democrats, who ruled for almost 50 years, underwent a severe crisis and eventually disbanded, splitting up into several factions. Moreover, the Communist Party was reorganised as a social-democratic force, the Democratic Party of the Left.

The "Second Republic"

In the midst of the ''mani pulite'' operation which shook political parties in 1994, media magnate

In the midst of the ''mani pulite'' operation which shook political parties in 1994, media magnate Silvio Berlusconi

Silvio Berlusconi ( ; ; 29 September 193612 June 2023) was an Italian Media proprietor, media tycoon and politician who served as the prime minister of Italy in three governments from 1994 to 1995, 2001 to 2006 and 2008 to 2011. He was a mem ...

, owner of three private TV channels, founded (Forward Italy) party and won the elections, becoming one of Italy's most important political and economic figures for the next decade. Berlusconi is also the longest-serving prime minister in the history of the Italian Republic and the third-longest serving in the whole history after Mussolini and Giolitti.

Ousted after a few months of government, Berlusconi returned to power in 2001, lost the 2006 general election five years later to Romano Prodi and his Union coalition, but won the 2008 general election and was elected prime minister for the third time in May 2008. In November 2011, Berlusconi lost his majority in the Chamber of Deputies and resigned. His successor, Mario Monti, formed a new government, composed of "technicians" and supported by both the center-left and the center-right. In April 2013, after the general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

in February, the Vice Secretary of the Democratic Party (PD) Enrico Letta led a government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

composed by both center-left and the center-right.

On 22 February 2014, after tensions in the Democratic Party the PD's Secretary Matteo Renzi was sworn in as the new prime minister. Renzi proposed several reforms, including a radical overhaul of the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

and a new electoral law. However, the proposed reforms were rejected on 4 December 2016 by a referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

. Following the referendum's results, Renzi resigned and his Foreign Affairs Minister Paolo Gentiloni was appointed new prime minister.

On 1 June 2018, after the 2018 Italian general election where the anti-establishment Five Star Movement become the largest party in Parliament, Giuseppe Conte

Giuseppe Conte (; born 8 August 1964) is an Italian jurist, academic, and politician who served as Prime Minister of Italy, prime minister of Italy from June 2018 to February 2021. He has been the president of the Five Star Movement (M5S) sin ...

(leader of Five Star) was sworn in as prime minister, at the head of a populist coalition of Five Star Movement and the League.

After the 2019 European Parliament election in Italy, where the League exceeded Five Star Movement, Matteo Salvini (leader of the League) proposed a no-confidence vote in Conte. Conte resigned, but after the consultations between the President

After the 2019 European Parliament election in Italy, where the League exceeded Five Star Movement, Matteo Salvini (leader of the League) proposed a no-confidence vote in Conte. Conte resigned, but after the consultations between the President Sergio Mattarella

Sergio Mattarella (; born 23 July 1941) is an Italian politician and jurist who has served as the president of Italy since 2015. He is the longest-serving president in the history of the Italian Republic. Since Giorgio Napolitano's death in 20 ...

and the political parties, Conte was reappointed as prime minister, heading a government of the Five Star Movement and the Democratic Party of Nicola Zingaretti.

In January 2021, the centrist party Italia Viva, led by former prime minister Renzi, withdrew its support to Conte's government. In February 2021, President Mattarella appointed Mario Draghi, former President of the European Central Bank

The European Central Bank (ECB) is the central component of the Eurosystem and the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) as well as one of seven institutions of the European Union. It is one of the world's Big Four (banking)#International ...

, Prime Minister. His new cabinet was supported by most Italian parties, including the League, M5S, PD, and FI.

In October 2022, President Mattarella appointed Giorgia Meloni as Italy's first female prime minister, following the resignation of Mario Draghi amidst a government crisis and a general election

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from By-election, by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. Gener ...

.

See also

* List of prime ministers of Italy * List of international trips made by prime ministers of Italy * Deputy Prime Minister of ItalyReferences

External links

Website of the Prime Minister of Italy

* {{Authority control Politics of Italy 1861 establishments in Italy Articles which contain graphical timelines la:Praeses consilii ministrorum