Poseidonius on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Posidonius (; grc-gre, ќ†ќњѕГќµќєќіѕОќљќєќњѕВ , "of

7.39-40

These three categories for him were, in Stoic fashion, inseparable and interdependent parts of an organic, natural whole. He compared them to a living being, with physics the flesh and blood, logic the bones and tendons holding the organism together, and finally ethicsвАФthe most important partвАФcorresponding to the soul. Although a firm Stoic, Posidonius was syncretic like Panaetius and other Stoics of the middle period. He followed not only the earlier Stoics, but made use of the writings of

Posidonius's fame beyond specialized philosophical circles had begun, at the latest, in the eighties with the publication of the work "'". This work was not only an overall representation of geographical questions according to current scientific knowledge, but it served to popularize his theories about the internal connections of the world, to show how all the forces had an effect on each other and how the interconnectedness applied also to human life, to the political just as to the personal spheres.

In this work, Posidonius detailed his theory of the effect on a people's character by the climate, which included his representation of the "geography of the races". This theory was not solely scientific, but also had political implicationsвАФhis Roman readers were informed that the climatic central position of Italy was an essential condition of the Roman destiny to dominate the world. As a Stoic, he did not, however, make a fundamental distinction between the civilized Romans as masters of the world and the less civilized peoples. Posidonius's writings on the Jews were probably the source of

Posidonius's fame beyond specialized philosophical circles had begun, at the latest, in the eighties with the publication of the work "'". This work was not only an overall representation of geographical questions according to current scientific knowledge, but it served to popularize his theories about the internal connections of the world, to show how all the forces had an effect on each other and how the interconnectedness applied also to human life, to the political just as to the personal spheres.

In this work, Posidonius detailed his theory of the effect on a people's character by the climate, which included his representation of the "geography of the races". This theory was not solely scientific, but also had political implicationsвАФhis Roman readers were informed that the climatic central position of Italy was an essential condition of the Roman destiny to dominate the world. As a Stoic, he did not, however, make a fundamental distinction between the civilized Romans as masters of the world and the less civilized peoples. Posidonius's writings on the Jews were probably the source of

fragment 202

/ref> His estimate of the latitude difference of these two points, 360/48=7.5, is rather erroneous. (The modern value is approximately 5 degrees.) In addition, they are not quite on the same meridian as they supposed to be. The longitude difference of the points, slightly less than 2 degrees, is not negligible compared with the latitude difference. Translating stadia into modern units of distance can be problematic, but it is generally thought that the stadium used by Posidonius was almost exactly 1/10 of a modern statute mile. Thus Posidonius's measure of 240,000 stadia translates to compared to the actual circumference of . Posidonius was informed in his approach to finding the Earth's circumference by

Posidonius was informed in his approach to finding the Earth's circumference by

In his own era, his writings on almost all the principal divisions of philosophy made Posidonius a renowned international figure throughout the Graeco-Roman world and he was widely cited by writers of his era, including

In his own era, his writings on almost all the principal divisions of philosophy made Posidonius a renowned international figure throughout the Graeco-Roman world and he was widely cited by writers of his era, including

Poseidonios

from ''Grosse Gestalten der griechischen Antike. 58 historische Portraits von Homer bis Kleopatra''. Hrsg. von Kai Brodersen. M√Љnchen: Verlag C.H. Beck. S. 426вАУ432. * * *

* ttp://www.attalus.org/translate/poseidonius.html Poseidonius: English translations of fragments about history and geography

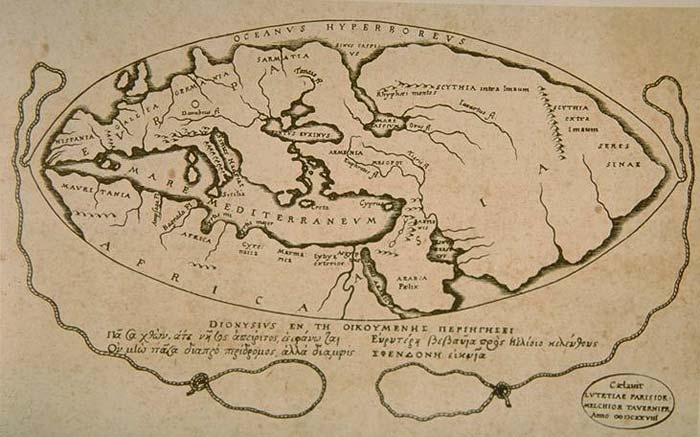

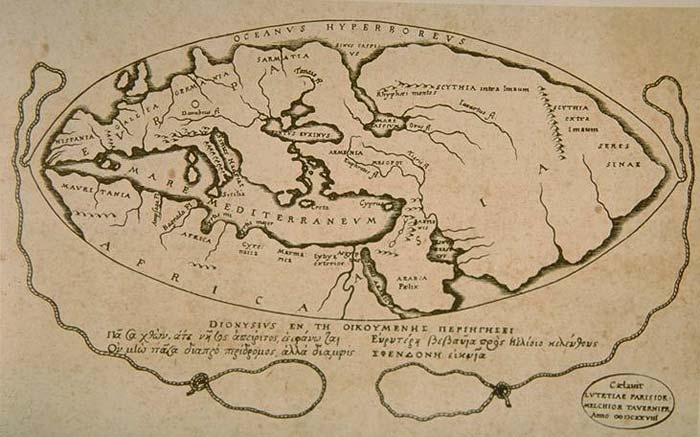

World map according to Posidonius

{{DEFAULTSORT:Posidonius 130s BC births 50s BC deaths Ancient Greek astronomers Hellenistic-era historians Roman-era Greek historians Ancient Greek mathematicians Geodesists Ancient Greek educators Hellenistic-era philosophers from Syria 1st-century BC Greek people 1st-century BC writers 1st-century BC historians 1st-century BC philosophers Stoic philosophers Syrian philosophers Syrian mathematicians Syrian astronomers Ancient Greek geographers Roman-era students in Athens Roman-era Rhodian philosophers Ancient Rhodian scientists Apamea, Syria 1st-century BC geographers 2nd-century BC Rhodians 1st-century BC Rhodians

Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, ќ†ќњѕГќµќєќібњґќљ) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136вАУ139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

") "of Apameia" (бљБ бЉИѕАќ±ќЉќµѕНѕВ) or "of Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, ќ°ѕМќіќњѕВ , translit=R√≥dos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

" (бљБ бњђѕМќіќєќњѕВ) (), was a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

, astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies вАУ in either o ...

, astrologer

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

, geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" a ...

, historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the st ...

, mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems.

Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, mathematical structure, structure, space, Mathematica ...

, and teacher native to Apamea, Syria. He was considered the most learned man of his time and, possibly, of the entire Stoic school. After a period learning Stoic philosophy

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting that ...

from Panaetius

Panaetius (; grc-gre, ќ†ќ±ќљќ±ќѓѕДќєќњѕВ, Pana√≠tios; вАУ ) of Rhodes was an ancient Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a pupil of Diogenes of Babylon and Antipater of Tarsus in Athens, before moving to Rome where he did much to introduce Stoic doc ...

in Athens

Athens ( ; el, ќСќЄќЃќљќ±, Ath√≠na ; grc, бЉИќЄбњЖќљќ±ќє, Ath√™nai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

, he spent many years in travel and scientific researches in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only durin ...

, Liguria

Liguria (; lij, Lig√їria ; french: Ligurie) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and on the eastern shores of the Adriatic. He settled as a teacher at Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, ќ°ѕМќіќњѕВ , translit=R√≥dos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

where his fame attracted numerous scholars. Next to Panaetius

Panaetius (; grc-gre, ќ†ќ±ќљќ±ќѓѕДќєќњѕВ, Pana√≠tios; вАУ ) of Rhodes was an ancient Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a pupil of Diogenes of Babylon and Antipater of Tarsus in Athens, before moving to Rome where he did much to introduce Stoic doc ...

he did most, by writings and personal lectures, to spread Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting that ...

to the Roman world, and he became well known to many leading men, including Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC вАУ 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

and Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC вАУ 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

.

His works are now lost, but they proved a mine of information to later writers. The titles and subjects of more than twenty of them are known. In common with other Stoics of the middle period, he displayed syncretic tendencies, following not just the earlier Stoics, but making use of the works of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, ќ†ќїќђѕДѕЙќљ ; 428/427 or 424/423 вАУ 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, бЉИѕБќєѕГѕДќњѕДќ≠ќїќЈѕВ ''Aristot√©lƒУs'', ; 384вАУ322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

. A polymath

A polymath ( el, ѕАќњќїѕЕќЉќ±ќЄќЃѕВ, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

as well as a philosopher, he took genuine interest in natural science, geography, natural history, mathematics and astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

. He sought to determine the distance and magnitude of the Sun, to calculate the diameter of the Earth and the influence of the Moon on the tides.

Life

Early life and education

Posidonius, nicknamed "the Athlete" (бЉИќЄќїќЈѕДќЃѕВ), was born around 135 BC. He was born into aGreek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

family in Apamea, a Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium i ...

city on the river Orontes in northern Syria. As historian Philip Freeman puts it: "Posidonius was Greek to the core". Posidonius expressed no love for his native city, Apamea, in his writings and he mocked its inhabitants.

As a young man he moved to Athens

Athens ( ; el, ќСќЄќЃќљќ±, Ath√≠na ; grc, бЉИќЄбњЖќљќ±ќє, Ath√™nai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

and studied under Panaetius

Panaetius (; grc-gre, ќ†ќ±ќљќ±ќѓѕДќєќњѕВ, Pana√≠tios; вАУ ) of Rhodes was an ancient Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a pupil of Diogenes of Babylon and Antipater of Tarsus in Athens, before moving to Rome where he did much to introduce Stoic doc ...

, the leading Stoic philosopher of the age, and the last undisputed head (scholarch

A scholarch ( grc, ѕГѕЗќњќїќђѕБѕЗќЈѕВ, ''scholarchƒУs'') was the head of a school in ancient Greece. The term is especially remembered for its use to mean the heads of schools of philosophy, such as the Platonic Academy in ancient Athens. Its fir ...

) of the Stoic school in Athens. When Panaetius died in 110 BC, Posidonius would have been around 25 years old. Rather than remain in Athens, he instead settled in Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, ќ°ѕМќіќњѕВ , translit=R√≥dos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

, and gained citizenship. In Rhodes, Posidonius maintained his own school which would become the leading institution of the time.

Travels

Around the 90s BC Posidonius embarked on a series of voyages around the Mediterranean gathering scientific data and observing the customs and people of the places he visited. He traveled in Greece,Hispania

Hispania ( la, HispƒБnia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: His ...

, Italy, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, stre ...

, Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only durin ...

, Liguria

Liguria (; lij, Lig√їria ; french: Ligurie) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is ...

, North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in t ...

, and on the eastern shores of the Adriatic.

In Hispania

Hispania ( la, HispƒБnia , ; nearly identically pronounced in Spanish, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian) was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: His ...

, on the Atlantic coast at Gades (the modern Cadiz), Posidonius could observe tides much higher than in his native Mediterranean. He wrote that daily tides are related to the Moon's orbit, while tidal heights vary with the cycles of the Moon, and he hypothesized about yearly tidal cycles synchronized with the equinoxes and solstices.

In Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only durin ...

, he studied the Celt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

s. He left vivid descriptions of things he saw with his own eyes while among them: men who were paid to allow their throats to be slit for public amusement and the nailing of skulls as trophies to the doorways. But he noted that the Celts honored the Druids

A druid was a member of the high-ranking class in ancient Celtic cultures. Druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no written accounts. Whi ...

, whom Posidonius saw as philosophers, and concluded that, even among the barbaric, "pride and passion give way to wisdom, and Ares stands in awe of the Muses." Posidonius wrote a geographic treatise on the lands of the Celt

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

s which has since been lost, but which is referred to extensively (both directly and otherwise) in the works of Diodorus of Sicily

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, ќФќєѕМќіѕЙѕБќњѕВ ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

, Strabo, Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC вАУ 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

and Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; вАУ ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major worksвАФthe ...

' ''Germania

Germania ( ; ), also called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman province of the same name, was a large historical region in north ...

''.

Political offices

InRhodes

Rhodes (; el, ќ°ѕМќіќњѕВ , translit=R√≥dos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

, Posidonius actively took part in political life, and he attained high office when he was appointed as one of the Prytaneis

The ''prytaneis'' (ѕАѕБѕЕѕДќђќљќµќєѕВ; sing.: ѕАѕБѕНѕДќ±ќљќєѕВ ''prytanis'') were the executives of the '' boule'' of ancient Athens.

Origins and organization

The term (like '' basileus'' or '' tyrannos'') is probably of Pre-Greek etymology (po ...

. This was the most important political office in Rhodes, combining presidential and executive functions, of which there were five (or possibly six) men holding the office for a six-month period.

He was chosen for at least one embassy to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

in 87/86, during the Marian

Marian may refer to:

People

* Mari people, a Finno-Ugric ethnic group in Russia

* Marian (given name), a list of people with the given name

* Marian (surname), a list of people so named

Places

*Marian, Iran (disambiguation)

* Marian, Queensla ...

and Sullan

''Sullan'' is a 2004 Indian Tamil-language action film written and directed by Ramana. It stars Dhanush, along with Sindhu Tolani, Manivannan, Pasupathy and Easwari Rao among others. The film was composed by Vidyasagar. The film was opened on ...

era. Although the purpose of the embassy is unknown, this was at the time of the First Mithridatic War

The First Mithridatic War (89вАУ85 BC) was a war challenging the Roman Republic's expanding empire and rule over the Greek world. In this conflict, the Kingdom of Pontus and many Greek cities rebelling against Roman rule were led by Mithridates ...

when Roman rule over the Greek cities was being challenged by Mithridates VI

Mithridates or Mithradates VI Eupator ( grc-gre, wikt:ќЬќєќЄѕБќ±ќіќђѕДќЈѕВ, ќЬќєќЄѕБќ±ќіќђѕДќЈѕВ; 135вАУ63 BC) was ruler of the Kingdom of Pontus in northern Anatolia from 120 to 63 BC, and one of the Roman Republic's most formidable and determi ...

of Pontus and the political situation was delicate.

The Stoic school on Rhodes

Under Posidonius,Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, ќ°ѕМќіќњѕВ , translit=R√≥dos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

eclipsed Athens

Athens ( ; el, ќСќЄќЃќљќ±, Ath√≠na ; grc, бЉИќЄбњЖќљќ±ќє, Ath√™nai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

to become the new centre for Stoic philosophy in the 1st century BC. This process may have already have begun under Panaetius

Panaetius (; grc-gre, ќ†ќ±ќљќ±ќѓѕДќєќњѕВ, Pana√≠tios; вАУ ) of Rhodes was an ancient Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a pupil of Diogenes of Babylon and Antipater of Tarsus in Athens, before moving to Rome where he did much to introduce Stoic doc ...

, who was a native of Rhodes, and may have fostered a school there. Ian Kidd remarks that Rhodes "was attractive, not only as an independent city, commercially prosperous, go-ahead and with easy links of movement in all directions, but because it was welcoming to intellectuals, for it already had a strong reputation particularly for scientific research from men like Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, бЉљѕАѕАќ±ѕБѕЗќњѕВ, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equ ...

."

Although little is known of the organization of his school, it is clear that Posidonius had a steady stream of Greek and Roman students, as demonstrated by the eminent Romans who visited it. Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC вАУ 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

sat in on a lecture in 66 and did so again in 62 on return from campaigning in the East. On this latter occasion the subject of the lecture was "There is no good but moral good". Posidonius was probably in his seventies at this time and was suffering from gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intens ...

. He illustrated the theme of his lecture by pointing to his painful leg and declaring "It is no good, pain; bothersome you may be, but you will never persuade me that you are an evil."

When Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC вАУ 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

was in his late twenties, he attended a course of Posidonius' lectures, and later invited Posidonius to write a monograph on Cicero's own consulship (Posidonius politely refused). In his later writings Cicero repeatedly refers to Posidonius as "my teacher" and "my dear friend". Posidonius died in his eighties in 51 BC; his grandson, Jason of Nysa

Jason of Nysa ( el, бЉЄќђѕГѕЙќљ бљБ ќЭѕЕѕГќ±ќµѕНѕВ, ''Iason o Nysaevs''; 1st-century BC) was a Stoic philosopher, the son of Menecrates, and, on his mother's side, grandson of Posidonius, of whom he was also the disciple and successor at the Stoic ...

, succeeded him as head of the school on Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, ќ°ѕМќіќњѕВ , translit=R√≥dos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

.

Partial scope of writings

Posidonius was celebrated as apolymath

A polymath ( el, ѕАќњќїѕЕќЉќ±ќЄќЃѕВ, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

throughout the Graeco-Roman world because he came near to mastering all the knowledge of his time, similar to Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, бЉИѕБќєѕГѕДќњѕДќ≠ќїќЈѕВ ''Aristot√©lƒУs'', ; 384вАУ322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

and Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, бЉШѕБќ±ѕДќњѕГќЄќ≠ќљќЈѕВ ; вАУ ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexand ...

. He attempted to create a unified system for understanding the human intellect and the universe which would provide an explanation of and a guide for human behavior.

Posidonius wrote on physics (including meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

and physical geography

Physical geography (also known as physiography) is one of the three main branches of geography. Physical geography is the branch of natural science which deals with the processes and patterns in the natural environment such as the atmosphere, ...

), astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

and divination, seismology

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek ѕГќµќєѕГќЉѕМѕВ (''seism√≥s'') meaning "earthquake" and -ќїќњќ≥ќѓќ± (''-log√≠a'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes and the propagation of elastic waves through the Earth or through other ...

, geology and mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proce ...

, hydrology

Hydrology () is the scientific study of the movement, distribution, and management of water on Earth and other planets, including the water cycle, water resources, and environmental watershed sustainability. A practitioner of hydrology is calle ...

, botany

Botany, also called plant science (or plant sciences), plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "bot ...

, ethics, logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premis ...

, mathematics, history, natural history, anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of be ...

, and tactics

Tactic(s) or Tactical may refer to:

* Tactic (method), a conceptual action implemented as one or more specific tasks

** Military tactics

Military tactics encompasses the art of organizing and employing fighting forces on or near the battlefiel ...

. His studies were major investigations into their subjects, although not without errors.

None of his works survive intact. All that have been found are fragments, although the titles and subjects of many of his books are known. Writers such as Strabo and Seneca provide most of the information about his life and works.

Philosophy

For Posidonius, philosophy was the dominant master art and all the individual sciences were subordinate to philosophy, which alone could explain the cosmos. All his works, from scientific to historical, were inseparably philosophical. He accepted the Stoic categorization of philosophy into physics (natural philosophy, including metaphysics and theology), logic (including dialectic), and ethics.Diogenes La√Ђrtius, ''The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers''7.39-40

These three categories for him were, in Stoic fashion, inseparable and interdependent parts of an organic, natural whole. He compared them to a living being, with physics the flesh and blood, logic the bones and tendons holding the organism together, and finally ethicsвАФthe most important partвАФcorresponding to the soul. Although a firm Stoic, Posidonius was syncretic like Panaetius and other Stoics of the middle period. He followed not only the earlier Stoics, but made use of the writings of

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, ќ†ќїќђѕДѕЙќљ ; 428/427 or 424/423 вАУ 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, бЉИѕБќєѕГѕДќњѕДќ≠ќїќЈѕВ ''Aristot√©lƒУs'', ; 384вАУ322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

. Posidonius studied Plato's ''Timaeus Timaeus (or Timaios) is a Greek name. It may refer to:

* ''Timaeus'' (dialogue), a Socratic dialogue by Plato

*Timaeus of Locri, 5th-century BC Pythagorean philosopher, appearing in Plato's dialogue

*Timaeus (historian) (c. 345 BC-c. 250 BC), Greek ...

'', and seems to have written a commentary on it emphasizing its Pythagorean features. As a creative philosopher, Posidonius would however be expected to create innovations within the tradition of the philosophical school to which he belonged. David Sedley

David Neil Sedley FBA (born 30 May 1947) is a British philosopher and historian of philosophy. He was the seventh Laurence Professor of Ancient Philosophy at Cambridge University.

Early life

Sedley was educated at Trinity College, Oxford where ...

remarks:

Ethics

Ethics, Posidonius taught, is about practice not just theory. It involves knowledge of both the human and the divine, and a knowledge of the universe to which human reason is related. It was once the general view that Posidonius departed from the monistic psychology of the earlier Stoics.Chrysippus

Chrysippus of Soli (; grc-gre, ќІѕБѕНѕГќєѕАѕАќњѕВ бљБ ќ£ќњќїќµѕНѕВ, ; ) was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was a native of Soli, Cilicia, but moved to Athens as a young man, where he became a pupil of the Stoic philosopher Cleanthes. When Cl ...

had written a work called ''On Passions

''On Passions'' ( el, ќ†ќµѕБбљґ ѕАќ±ќЄбњґќљ; ''Peri path≈Нn''), also translated as ''On Emotions'' or ''On Affections'', is a work by the Greek Stoic philosopher Chrysippus dating from the 3rd-century BCE. The book has not survived intact, but aro ...

'' in which he affirmed that reason and emotion were not separate and distinct faculties, and that destructive passions were instead rational impulses which were out-of-control. According to the testimony of Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, ќЪќїќ±ѕНќіќєќњѕВ ќУќ±ќїќЈќљѕМѕВ; September 129 вАУ c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be on ...

(an adherent of Plato), Posidonius wrote his own ''On Passions'' in which he instead adopted Plato's tripartition of the soul which taught that in addition to the rational faculties, the human soul had faculties that were spirited (anger, desires for power, possessions, etc.) and desiderative (desires for sex and food). Although Galen's testimony is still accepted by some, more recent scholarship argues that Galen may have exaggerated Posidonius' views for polemical effect, and that Posidonius may have been trying to clarify and expand on Chrysippus rather than oppose him. Other writers who knew the ethical works of Posidonius, including Cicero and Seneca, grouped Chrysippus and Posidonius together and saw no opposition between them.

Physics

The philosophical grand vision of Posidonius was that the universe itself was interconnected as an organic whole, providential and organised in all respects, from the development of the physical world to the behaviour of living creatures. Panaetius had doubted both the reality of divination and the Stoic doctrine of the future conflagration (ekpyrosis

Ekpyrosis (; grc, бЉРќЇѕАѕНѕБѕЙѕГќєѕВ ''ekp√љr≈Нsis'', "conflagration") is a Stoic belief in the periodic destruction of the cosmos by a great conflagration every Great Year. The cosmos is then recreated (palingenesis) only to be destroyed again ...

), but Posidonius wrote in favour of these ideas. As a Stoic, Posidonius was an advocate of cosmic "sympathy" (ѕГѕЕќЉѕАќђќЄќµќєќ±, ''sympatheia'')вАФthe organic interrelation of all appearances in the world, from the sky to the Earth, as part of a rational design uniting humanity and all things in the universe. He believed valid predictions could made from signs in natureвАФwhether through astrology or prophetic dreamsвАФas a kind of scientific prediction.

Mathematics

Posidonius was one of the first to attempt to prove Euclid's fifth postulate of geometry. He suggested changing the definition of parallel straight lines to an equivalent statement that would allow him to prove the fifth postulate. From there, Euclidean geometry could be restructured, placing the fifth postulate among the theorems instead. In addition to his writings on geometry, Posidonius was credited for creating some mathematical definitions, or for articulating views on technical terms, for example 'theorem' and 'problem'.Astronomy and Meteorology

Some fragments of his writings on astronomy survive through the treatise by Cleomedes, ''On the Circular Motions of the Celestial Bodies'', the first chapter of the second book appearing to have been mostly copied from Posidonius. Posidonius advanced the theory that the Sun emanated a vital force that permeated the world. He attempted to measure the distance and size of theSun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared rad ...

. In about 90 BC, Posidonius estimated the distance from the Earth to the Sun (see astronomical unit

The astronomical unit (symbol: au, or or AU) is a unit of length, roughly the distance from Earth to the Sun and approximately equal to or 8.3 light-minutes. The actual distance from Earth to the Sun varies by about 3% as Earth orbi ...

) to be 9,893 times the Earth's radius. This was still too small by half. In measuring the size of the Sun, however, he reached a figure larger and more accurate than those proposed by other Greek astronomers and Aristarchus of Samos.

Posidonius also calculated the size and distance of the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width ...

.

Posidonius constructed an orrery

An orrery is a mechanical model of the Solar System that illustrates or predicts the relative positions and motions of the planets and moons, usually according to the heliocentric model. It may also represent the relative sizes of these bodies ...

, possibly similar to the Antikythera mechanism

The Antikythera mechanism ( ) is an Ancient Greek hand-powered orrery, described as the oldest example of an analogue computer used to predict astronomical positions and eclipses decades in advance. It could also be used to track the four-y ...

. Posidonius's orrery, according to Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC вАУ 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

, exhibited the diurnal motions of the Sun, Moon, and the five known planets.

Posidonius in his writings on meteorology followed Aristotle. He theorized on the causes of clouds, mist, wind, and rain as well as frost, hail, lightning, and rainbows. He also estimated that the boundary between the clouds and the heavens lies about 40 stadia above the Earth.

Geography, ethnology, and geology

Posidonius's fame beyond specialized philosophical circles had begun, at the latest, in the eighties with the publication of the work "'". This work was not only an overall representation of geographical questions according to current scientific knowledge, but it served to popularize his theories about the internal connections of the world, to show how all the forces had an effect on each other and how the interconnectedness applied also to human life, to the political just as to the personal spheres.

In this work, Posidonius detailed his theory of the effect on a people's character by the climate, which included his representation of the "geography of the races". This theory was not solely scientific, but also had political implicationsвАФhis Roman readers were informed that the climatic central position of Italy was an essential condition of the Roman destiny to dominate the world. As a Stoic, he did not, however, make a fundamental distinction between the civilized Romans as masters of the world and the less civilized peoples. Posidonius's writings on the Jews were probably the source of

Posidonius's fame beyond specialized philosophical circles had begun, at the latest, in the eighties with the publication of the work "'". This work was not only an overall representation of geographical questions according to current scientific knowledge, but it served to popularize his theories about the internal connections of the world, to show how all the forces had an effect on each other and how the interconnectedness applied also to human life, to the political just as to the personal spheres.

In this work, Posidonius detailed his theory of the effect on a people's character by the climate, which included his representation of the "geography of the races". This theory was not solely scientific, but also had political implicationsвАФhis Roman readers were informed that the climatic central position of Italy was an essential condition of the Roman destiny to dominate the world. As a Stoic, he did not, however, make a fundamental distinction between the civilized Romans as masters of the world and the less civilized peoples. Posidonius's writings on the Jews were probably the source of Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, ќФќєѕМќіѕЙѕБќњѕВ ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

's account of the siege of Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, „Щ÷∞„®„Х÷Љ„©÷Є„Б„Ь÷Ј„Щ÷і„Э ; ar, ЎІўДўВўПЎѓЎ≥ ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, бЉєќµѕБќњѕЕѕГќ±ќїќЃќЉ/бЉЄќµѕБќњѕГѕМќїѕЕќЉќ±, HierousalбЄЧm/Hieros√≥luma; hy, ‘µ÷А’Є÷В’љ’°’≤’•’і, Erusa≈ВƒУm. i ...

and possibly also for Strabo's. Some of Posidonius's arguments are contested by Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, бЉЄѕОѕГќЈѕАќњѕВ, ; 37 вАУ 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in JerusalemвАФthen part of Roman JudeaвАФto a father of priestly d ...

in ''Against Apion

''Against Apion'' ( el, ќ¶ќїќ±ќРќњѕЕ бЉЄѕЙѕГќЃѕАќњѕЕ ѕАќµѕБбљґ бЉАѕБѕЗќ±ќєѕМѕДќЈѕДќњѕВ бЉЄќњѕЕќіќ±ќѓѕЙќљ ќїѕМќ≥ќњѕВ ќ± and ; Latin ''Contra Apionem'' or ''In Apionem'') is a polemical work written by Flavius Josephus as a defense of Judaism as a ...

''.

Like Pytheas

Pytheas of Massalia (; Ancient Greek: ќ†ѕЕќЄќ≠ќ±ѕВ бљБ ќЬќ±ѕГѕГќ±ќїќєѕОѕДќЈѕВ ''Pyth√©as ho Massali≈НtƒУs''; Latin: ''Pytheas Massiliensis''; born 350 BC, 320вАУ306 BC) was a Greek geographer, explorer and astronomer from the Greek colo ...

, Posidonius believed the tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables can ...

is caused by the Moon. Posidonius was, however, wrong about the cause. Thinking that the Moon was a mixture of air and fire, he attributed the cause of the tides to the heat of the Moon, hot enough to cause the water to swell but not hot enough to evaporate it.

He recorded observations on both earthquakes and volcanoes, including accounts of the eruptions of the volcanoes in the Aeolian Islands

The Aeolian Islands ( ; it, Isole Eolie ; scn, √Мsuli Eoli), sometimes referred to as the Lipari Islands or Lipari group ( , ) after their largest island, are a volcanic archipelago in the Tyrrhenian Sea north of Sicily, said to be named a ...

, north of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

.

Earth's circumference

Posidonius calculated theEarth's circumference

Earth's circumference is the distance around Earth. Measured around the Equator, it is . Measured around the poles, the circumference is .

Measurement of Earth's circumference has been important to navigation since ancient times. The first kn ...

by the arc measurement

Arc measurement, sometimes degree measurement (german: Gradmessung), is the astrogeodetic technique of determining of the radius of Earth вАУ more specifically, the local Earth radius of curvature of the figure of the Earth вАУ by relating the l ...

method, by reference to the position of the star Canopus

Canopus is the brightest star in the southern constellation of Carina and the second-brightest star in the night sky. It is also designated ќ± Carinae, which is Latinised to Alpha Carinae. With a visual apparent magnitude of ...

. As explained by Cleomedes, Posidonius observed Canopus on but never above the horizon at Rhodes, while at Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ў±ўДўТЎ•ўРЎ≥ўТўГўОўЖўТЎѓўОЎ±ўРўКўОўСЎ©ўП ; grc-gre, ќСќїќµќЊќђќљќіѕБќµќєќ±, Alex√°ndria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

he saw it ascend as far as 7¬љ degrees above the horizon (the meridian arc

In geodesy and navigation, a meridian arc is the curve between two points on the Earth's surface having the same longitude. The term may refer either to a segment of the meridian, or to its length.

The purpose of measuring meridian arcs is to ...

between the latitude of the two locales is actually 5 degrees 14 minutes). Since he thought Rhodes was 5,000 stadia due north of Alexandria, and the difference in the star's elevation indicated the distance between the two locales was 1/48 of the circle, he multiplied 5,000 by 48 to arrive at a figure of 240,000 stadia for the circumference of the Earth.Posidoniusfragment 202

/ref> His estimate of the latitude difference of these two points, 360/48=7.5, is rather erroneous. (The modern value is approximately 5 degrees.) In addition, they are not quite on the same meridian as they supposed to be. The longitude difference of the points, slightly less than 2 degrees, is not negligible compared with the latitude difference. Translating stadia into modern units of distance can be problematic, but it is generally thought that the stadium used by Posidonius was almost exactly 1/10 of a modern statute mile. Thus Posidonius's measure of 240,000 stadia translates to compared to the actual circumference of .

Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, бЉШѕБќ±ѕДќњѕГќЄќ≠ќљќЈѕВ ; вАУ ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexand ...

, who a century earlier arrived at a figure of 252,000 stadia; both men's figures for the Earth's circumference were uncannily accurate.

Strabo noted that the distance between Rhodes and Alexandria is 3,750 stadia, and reported Posidonius's estimate of the Earth's circumference to be 180,000 stadia or . Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ...

mentions Posidonius among his sources and without naming him reported his method for estimating the Earth's circumference. He noted, however, that Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, бЉљѕАѕАќ±ѕБѕЗќњѕВ, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equ ...

had added some 26,000 stadia to Eratosthenes's estimate. The smaller value offered by Strabo and the different lengths of Greek and Roman stadia have created a persistent confusion around Posidonius's result. Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, ќ†ѕДќњќїќµќЉќ±бњЦќњѕВ, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

used Posidonius's lower value of 180,000 stades (about 33% too low) for the Earth's circumference in his ''Geography''. This was the number used by Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

to underestimate the distance to India as 70,000 stades.

History and tactics

In his ''Histories'', Posidonius continued the ''World History'' ofPolybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, ќ†ќњќїѕНќ≤ќєќњѕВ, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264вАУ146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

. His history of the period 146вАУ88 BC is said to have filled 52 volumes. His ''Histories'' continue the account of the rise and expansion of Roman dominance, which he appears to have supported. Posidonius did not follow Polybius's more detached and factual style, for Posidonius saw events as caused by human psychology; while he understood human passions and follies, he did not pardon or excuse them in his historical writing, using his narrative skill in fact to enlist the readers' approval or condemnation.

For Posidonius "history" extended beyond the earth into the sky; humanity was not isolated each in its own political history, but was a part of the cosmos. His ''Histories'' were not, therefore, concerned with isolated political history of peoples and individuals, but they included discussions of all forces and factors (geographical factors, mineral resources, climate, nutrition), which let humans act and be a part of their environment. For example, Posidonius considered the climate of Arabia and the life-giving strength of the sun, tides (taken from his book on the oceans), and climatic theory to explain people's ethnic or national characters.

Of Posidonius's work on tactics, ''The Art of War'', the Greek historian Arrian

Arrian of Nicomedia (; Greek: ''Arrianos''; la, Lucius Flavius Arrianus; )

was a Greek historian, public servant, military commander and philosopher of the Roman period.

'' The Anabasis of Alexander'' by Arrian is considered the best ...

complained that it was written 'for experts', which suggests that Posidonius may have had first hand experience of military leadership or, perhaps, used knowledge he gained from his acquaintance with Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC вАУ 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

.

Reputation and influence

In his own era, his writings on almost all the principal divisions of philosophy made Posidonius a renowned international figure throughout the Graeco-Roman world and he was widely cited by writers of his era, including

In his own era, his writings on almost all the principal divisions of philosophy made Posidonius a renowned international figure throughout the Graeco-Roman world and he was widely cited by writers of his era, including Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC вАУ 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

, Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC вАУ AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, ќ†ќїќњѕНѕДќ±ѕБѕЗќњѕВ, ''Plo√Їtarchos''; ; вАУ after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ...

, Strabo (who called Posidonius "the most learned of all philosophers of my time"), Cleomedes, Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (; 65 AD), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and, in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca was ...

, Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, ќФќєѕМќіѕЙѕБќњѕВ ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

(who used Posidonius as a source for his ''Bibliotheca historia'' Historical Library", and others. Although his ornate and rhetorical style of writing passed out of fashion soon after his death, Posidonius was acclaimed during his life for his literary ability and as a stylist.

Posidonius was the major source of materials on the Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

of Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only durin ...

and was profusely quoted by Timagenes, Julius Caesar, the Sicilian Greek Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, ќФќєѕМќіѕЙѕБќњѕВ ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

, and the Greek geographer Strabo.

Posidonius appears to have moved with ease among the upper echelons of Roman society as an ambassador from Rhodes. He associated with some of the leading figures of late republican Rome, including Cicero and Pompey, both of whom visited him in Rhodes. In his twenties, Cicero attended his lectures (77 BC) and they continued to correspond. Cicero in his ''De Finibus'' closely followed Posidonius's presentation of Panaetius's ethical teachings.

Posidonius met Pompey when he was Rhodes's ambassador in Rome and Pompey visited him in Rhodes twice, once in 66 BC during his campaign against the pirates and again in 62 BC during his eastern campaigns, and asked Posidonius to write his biography. As a gesture of respect and great honor, Pompey lowered his '' fasces'' before Posidonius's door. Other Romans who visited Posidonius in Rhodes were Velleius, Cotta, and Lucilius

The gens Lucilia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. The most famous member of this gens was the poet Gaius Lucilius, who flourished during the latter part of the second century BC.''Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology'', vo ...

.

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, ќ†ѕДќњќїќµќЉќ±бњЦќњѕВ, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

was impressed by the sophistication of Posidonius's methods, which included correcting for the refraction of light passing through denser air near the horizon. Ptolemy's approval of Posidonius's result, rather than Eratosthenes's earlier and more correct figure, caused it to become the accepted value for the Earth's circumference for the next 1,500 years.

Posidonius fortified the Stoicism of the middle period with contemporary learning. Next to his teacher Panaetius, he did most, by writings and personal contacts, to spread Stoicism in the Roman world. A century later, Seneca referred to Posidonius as one of those who had made the largest contribution to philosophy.

His influence on Greek philosophical thinking lasted until the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, as is demonstrated by the large number of times he is cited as a source in the ''Suda

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; grc-x-medieval, ќ£ќњбњ¶ќіќ±, So√їda; la, Suidae Lexicon) is a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas (ќ£ќњѕНќіќ±ѕВ) or Souidas ...

'' (a 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia).

Wilhelm Capelle traced most of the doctrines of the popular philosophic treatise ''De Mundo

''On the Universe'' ( el, ќ†ќµѕБбљґ ќЪѕМѕГќЉќњѕЕ; la, De Mundo) is a theological and scientific treatise included in the Corpus Aristotelicum but usually regarded as spurious. It was likely published between and the . The work discusses cosmo ...

'' to Posidonius. Today, Posidonius seems to be recognized as having had an inquiring and wide-ranging mind, not entirely original, but with a breadth of view that connected, in accordance with his underlying Stoic philosophy, all things and their causes and all knowledge into an overarching, unified world view.

The crater Posidonius

Posidonius (; grc-gre, wikt:ќ†ќњѕГќµќєќіѕОќљќєќњѕВ, ќ†ќњѕГќµќєќіѕОќљќєќњѕВ , "of Poseidon") "of Apamea (Syria), Apameia" (бљБ бЉИѕАќ±ќЉќµѕНѕВ) or "of Rhodes" (бљБ бњђѕМќіќєќњѕВ) (), was a Greeks, Greek politician, astronomer, astrologer, geog ...

on the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width ...

is named after him.

See also

*Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, бЉШѕБќ±ѕДќњѕГќЄќ≠ќљќЈѕВ ; вАУ ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexand ...

(), a Greek mathematician who calculated the circumference of the Earth and also the distance from the Earth to the Sun.

* Twin study

Twin studies are studies conducted on identical or fraternal twins. They aim to reveal the importance of environmental and genetic influences for traits, phenotypes, and disorders. Twin research is considered a key tool in behavioral genetics ...

References

Sources

* * Bevan, Edwyn. ''Stoics and Skeptics'', 1913. * * Harley, J. B. & Woodward, David. ''The History of Cartography, Volume 1: Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean'', 1987, pp. 168вАУ170. (v. 1) * Ian G. Kidd and Ludwig Edelstein (eds.), ''Posidonius'', ''The Fragments'', vol. I, Cambridge University Press, 1972. * * * Juergen MalitzPoseidonios

from ''Grosse Gestalten der griechischen Antike. 58 historische Portraits von Homer bis Kleopatra''. Hrsg. von Kai Brodersen. M√Љnchen: Verlag C.H. Beck. S. 426вАУ432. * * *

Further reading

* Freeman, Phillip, ''The Philosopher and the Druids: A Journey Among The Ancient Celts'', Simon and Schuster, 2006. * Irvine, William B. (2008) ''A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy'', Oxford University Press. вАФ Discussion of his work and influenceExternal links

* ttp://www.attalus.org/translate/poseidonius.html Poseidonius: English translations of fragments about history and geography

World map according to Posidonius

{{DEFAULTSORT:Posidonius 130s BC births 50s BC deaths Ancient Greek astronomers Hellenistic-era historians Roman-era Greek historians Ancient Greek mathematicians Geodesists Ancient Greek educators Hellenistic-era philosophers from Syria 1st-century BC Greek people 1st-century BC writers 1st-century BC historians 1st-century BC philosophers Stoic philosophers Syrian philosophers Syrian mathematicians Syrian astronomers Ancient Greek geographers Roman-era students in Athens Roman-era Rhodian philosophers Ancient Rhodian scientists Apamea, Syria 1st-century BC geographers 2nd-century BC Rhodians 1st-century BC Rhodians