Portage County Tallmadge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Portage or portaging (

Portage or portaging (

Going upstream was more difficult, as there were many places where the current was too swift to paddle. Where the river bottom was shallow and firm, voyageurs would stand in the canoe and push it upstream with poles. If the shoreline was reasonably clear the canoe could be 'tracked' or 'lined', that is, the canoemen would pull the canoe on a rope while one man stayed on board to keep it away from the shore. (The most extreme case of tracking was in the

Going upstream was more difficult, as there were many places where the current was too swift to paddle. Where the river bottom was shallow and firm, voyageurs would stand in the canoe and push it upstream with poles. If the shoreline was reasonably clear the canoe could be 'tracked' or 'lined', that is, the canoemen would pull the canoe on a rope while one man stayed on board to keep it away from the shore. (The most extreme case of tracking was in the

The '' Diolkos'' was a paved trackway in

The '' Diolkos'' was a paved trackway in

The land link between

The land link between

In the 8th, 9th and 10th centuries,

In the 8th, 9th and 10th centuries,

Portage or portaging (

Portage or portaging (Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

: ; ) is the practice of carrying water craft or cargo over land, either around an obstacle in a river, or between two bodies of water. A path where items are regularly carried between bodies of water is also called a ''portage.'' The term comes from French, where means "to carry," as in "portable". In Canada, the term "carrying-place" was sometimes used.

Early French explorers in New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spa ...

and French Louisiana

The term French Louisiana refers to two distinct regions:

* first, to colonial French Louisiana, comprising the massive, middle section of North America claimed by France during the 17th and 18th centuries; and,

* second, to modern French Louisi ...

encountered many rapids and cascades. The Native Americans carried their canoe

A canoe is a lightweight narrow water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using a single-bladed paddle.

In British English, the ter ...

s over land to avoid river obstacles.

Over time, important portages were sometimes provided with canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface flo ...

s with locks

Lock(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

*Lock and key, a mechanical device used to secure items of importance

*Lock (water navigation), a device for boats to transit between different levels of water, as in a canal

Arts and entertainment

* ''Lock ...

, and even portage railway

A portage railway is a short and possibly isolated section of railway used to bypass a section of unnavigable river or between two water bodies which are not directly connected.

Cargo from waterborne vessels is unloaded, loaded onto conventional ...

s. Primitive portaging generally involves carrying the vessel and its contents across the portage in multiple trips. Small canoes can be portaged by carrying them inverted over one's shoulders and the center strut

A strut is a structural component commonly found in engineering, aeronautics, architecture and anatomy. Struts generally work by resisting longitudinal compression, but they may also serve in tension.

Human anatomy

Part of the functionality o ...

may be designed in the style of a yoke

A yoke is a wooden beam sometimes used between a pair of oxen or other animals to enable them to pull together on a load when working in pairs, as oxen usually do; some yokes are fitted to individual animals. There are several types of yoke, u ...

to facilitate this. Historically, voyageurs

The voyageurs (; ) were 18th and 19th century French Canadians who engaged in the transporting of furs via canoe during the peak of the North American fur trade. The emblematic meaning of the term applies to places (New France, including th ...

often employed tump lines on their heads to carry loads on their backs.

Portages can be many kilometers in length, such as the Methye Portage

The Methye Portage or Portage La Loche in northwestern Saskatchewan was one of the most important portages in the old fur trade route across Canada. The portage connected the Mackenzie River basin to rivers that ran east to the Atlantic. It wa ...

and the Grand Portage

Grand Portage National Monument is a United States National Monument located on the north shore of Lake Superior in northeastern Minnesota that preserves a vital center of fur trade activity and Anishinaabeg Ojibwe heritage. The area became one ...

(both in North America) often covering hilly or difficult terrain. Some portages involve very little elevation change, such as the very short Mavis Grind

Mavis Grind ( non, Mæfeiðs grind or ', meaning "gate of the narrow isthmus") is a narrow isthmus joining the Northmavine peninsula to the rest of the island of Shetland Mainland in the Shetland Islands, Scotland.

It is said to be the only plac ...

in Shetland, which crosses an isthmus

An isthmus (; ; ) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea counterpart of an isthmus ...

.

Technique

This section deals mostly with the heavy freight canoes used by the CanadianVoyageurs

The voyageurs (; ) were 18th and 19th century French Canadians who engaged in the transporting of furs via canoe during the peak of the North American fur trade. The emblematic meaning of the term applies to places (New France, including th ...

.

Portage trails usually began as animal tracks and were improved by tramping or blazing. In a few places iron-plated wooden rails were laid to take a handcart. Heavily used routes sometimes evolved into roads when sledges, rollers or oxen were used, as at Methye Portage

The Methye Portage or Portage La Loche in northwestern Saskatchewan was one of the most important portages in the old fur trade route across Canada. The portage connected the Mackenzie River basin to rivers that ran east to the Atlantic. It wa ...

. Sometimes railways ( Champlain and St. Lawrence Railroad) or canals were built.

When going downstream through rapids an experienced voyageur called the ''guide'' would inspect the rapids and choose between the heavy work of a portage and the life-threatening risk of running the rapids. If the second course were chosen, the boat would be controlled by the ''avant'' standing in front with a long paddle and the ''gouvernail'' standing in the back with a steering paddle. The ''avant'' had a better view and was in charge but the ''gouvernail'' had more control over the boat. The other canoemen provided power under the instructions of the ''avant.''

Going upstream was more difficult, as there were many places where the current was too swift to paddle. Where the river bottom was shallow and firm, voyageurs would stand in the canoe and push it upstream with poles. If the shoreline was reasonably clear the canoe could be 'tracked' or 'lined', that is, the canoemen would pull the canoe on a rope while one man stayed on board to keep it away from the shore. (The most extreme case of tracking was in the

Going upstream was more difficult, as there were many places where the current was too swift to paddle. Where the river bottom was shallow and firm, voyageurs would stand in the canoe and push it upstream with poles. If the shoreline was reasonably clear the canoe could be 'tracked' or 'lined', that is, the canoemen would pull the canoe on a rope while one man stayed on board to keep it away from the shore. (The most extreme case of tracking was in the Three Gorges

The Three Gorges () are three adjacent gorges along the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, in the hinterland of the People's Republic of China. With a subtropical monsoon climate, they are known for their scenery. The "Three Gorges Scenic A ...

in China where all boats had to be pulled upstream against the current of the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest list of rivers of Asia, river in Asia, the list of rivers by length, third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in th ...

.) In worse conditions, the 'demi-chargé' technique was used. Half the cargo was unloaded, the canoe forced upstream, unloaded and then returned downstream to pick up the remaining half of the cargo. In still worse currents, the entire cargo was unloaded ('décharge') and carried overland while the canoe was forced upstream. In the worst case a full portage was necessary. The canoe was carried overland by two or four men (the heavier York boats

The York boat was a type of inland boat used by the Hudson's Bay Company to carry furs and trade goods along inland waterways in Rupert's Land, the watershed stretching from Hudson Bay to the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains. It was named af ...

had to be dragged overland on rollers) The cargo was divided into standard packs or ''pièces'' with each man responsible for about six. One portage or canoe pack

A canoe pack, also known as a portage pack, is a specialized type of backpack used primarily where travel is largely by water punctuated by portages where the gear needs to be carried over land.

When worn, a canoe pack must ride below the level of ...

would be carried by a tumpline

A tumpline () is a strap attached at both ends to a sack, backpack, or other luggage and used to carry the object by placing the strap over the top of the head. This utilizes the spine rather than the shoulders as standard backpack straps do. ...

and one on the back (strangulated hernia

A hernia is the abnormal exit of tissue or an organ, such as the bowel, through the wall of the cavity in which it normally resides. Various types of hernias can occur, most commonly involving the abdomen, and specifically the groin. Groin hernia ...

was a common cause of death). To allow regular rests the voyageur would drop his pack at a ''pose'' about every and go back for the next load. The time for a portage was estimated at one hour per half mile.

History

Europe

Greco-Roman world

The '' Diolkos'' was a paved trackway in

The '' Diolkos'' was a paved trackway in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of Classical Antiquity, classical antiquity ( AD 600), th ...

which enabled boats to be moved overland across the Isthmus of Corinth between the Gulf of Corinth and the Saronic Gulf

The Saronic Gulf (Greek: Σαρωνικός κόλπος, ''Saronikós kólpos'') or Gulf of Aegina in Greece is formed between the peninsulas of Attica and Argolis and forms part of the Aegean Sea. It defines the eastern side of the isthmus of Co ...

. It was constructed to transport high ranking Despots to conduct business in the justice system. The roadway was a rudimentary form of railway

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

, and operated from around 600 BC until the middle of the 1st century AD.

The scale on which the Diolkos combined the two principles of the railway and the overland transport of ships was unique in antiquity.

There is scant literary evidence for two more ship trackways referred to as diolkoi in antiquity, both located in Roman Egypt: The physician Oribasius

Oribasius or Oreibasius ( el, Ὀρειβάσιος; c. 320 – 403) was a Greek medical writer and the personal physician of the Roman emperor Julian. He studied at Alexandria under physician Zeno of Cyprus before joining Julian's retinue. He ...

() records two passages from his first-century colleague Xenocrates

Xenocrates (; el, Ξενοκράτης; c. 396/5314/3 BC) of Chalcedon was a Greek philosopher, mathematician, and leader ( scholarch) of the Platonic Academy from 339/8 to 314/3 BC. His teachings followed those of Plato, which he attempted t ...

, in which the latter casually refers to a diolkos close to the harbor of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, which may have been located at the southern tip of the island of Pharos. Another diolkos is mentioned by Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

(90–168 CE) in his book on geography (IV, 5, 10) as connecting a false mouth of a partly silted up Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered the longest ...

branch with the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

.

Writing in the first half of the eighth century, Cosmas of Jerusalem describes the portage of boats across the narrowest part of the Thracian Chersonese

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied ...

(Gallipoli Peninsula) between the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans ...

and the Sea of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara,; grc, Προποντίς, Προποντίδα, Propontís, Propontída also known as the Marmara Sea, is an inland sea located entirely within the borders of Turkey. It connects the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea via t ...

. The peninsula there is six miles wide. Cosmas describes the dragging of small boats as common in his day for local trade between Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to ...

and Gothograecia. The motivation for this practice was to avoid the long detour around the peninsula and through the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

, but also to avoid the customs house at Abydos. It would have been too costly to regularly move large ships across the peninsula, but Cosmas says that Constantine IV

Constantine IV ( la, Constantinus; grc-gre, Κωνσταντῖνος, Kōnstantînos; 650–685), called the Younger ( la, iunior; grc-gre, ὁ νέος, ho néos) and sometimes incorrectly the Bearded ( la, Pogonatus; grc-gre, Πωγων ...

did it, presumably during the blockade of Constantinople (670/1–676/7) when the Sea of Marmara and the Dardanelles were controlled by the Umayyads Umayyads may refer to:

*Umayyad dynasty, a Muslim ruling family of the Caliphate (661–750) and in Spain (756–1031)

*Umayyad Caliphate (661–750)

:*Emirate of Córdoba (756–929)

:*Caliphate of Córdoba

The Caliphate of Córdoba ( ar, خ ...

. Constantine is said to have "driven" the ships rather than dragged them, probably indicating the use of wheels. Archaeological evidence for a portage across the Thracian Chersonese is lacking, but it is possible that traces of it have been confused with traces of the Long Wall, which was restored by Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renova ...

in the 6th century. The region also saw extensive damage during the Gallipoli Campaign of 1915.

Venetian Republic

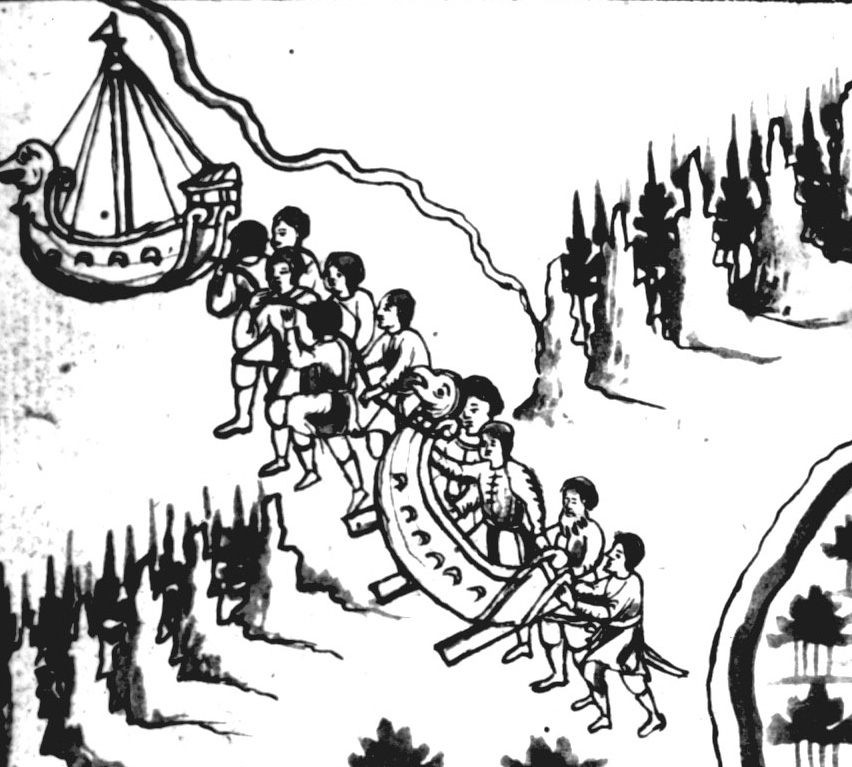

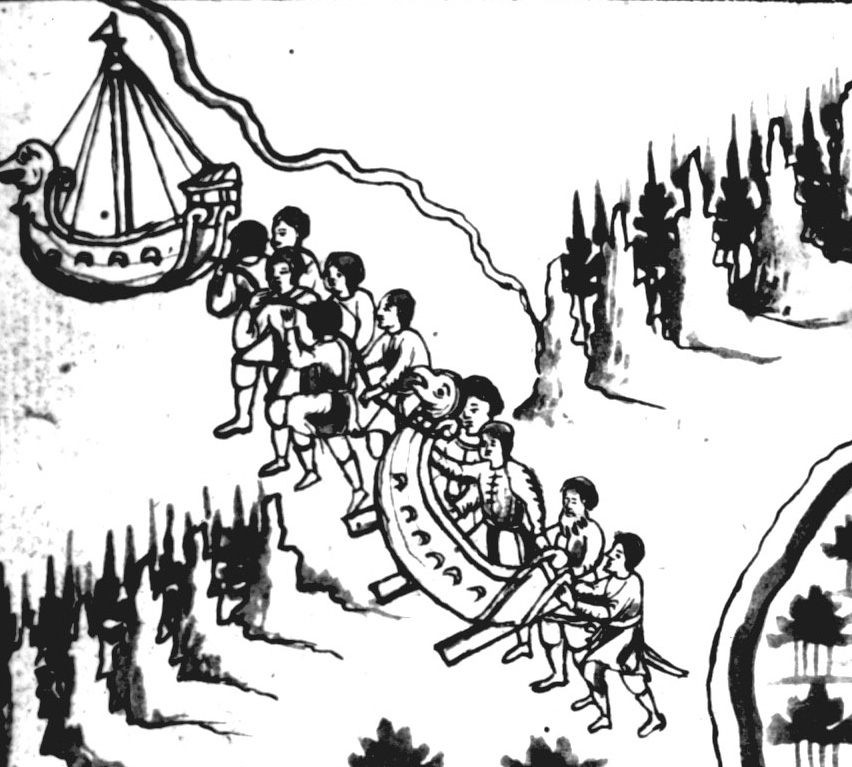

The land link between

The land link between Adige

The Adige (; german: Etsch ; vec, Àdexe ; rm, Adisch ; lld, Adesc; la, Athesis; grc, Ἄθεσις, Áthesis, or , ''Átagis'') is the second-longest river in Italy, after the Po. It rises near the Reschen Pass in the Vinschgau in the pro ...

River and Garda Lake in Northern Italy, hardly used by the smallest watercraft, was at least once used by the Venetian Republic

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia ...

for the transport of a military fleet in 1439. The land link is now somewhat harder because of the disappearance of Loppio Lake.

Russia

In the 8th, 9th and 10th centuries,

In the 8th, 9th and 10th centuries, Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

merchant-adventurers exploited a network of waterways in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whic ...

, with portages connecting the four most important rivers of the region: Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchm ...

, Western Dvina

, be, Заходняя Дзвіна (), liv, Vēna, et, Väina, german: Düna

, image = Fluss-lv-Düna.png

, image_caption = The drainage basin of the Daugava

, source1_location = Valdai Hills, Russia

, mouth_location = Gulf of Riga, Baltic Se ...

, Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

, and Don

Don, don or DON and variants may refer to:

Places

*County Donegal, Ireland, Chapman code DON

*Don (river), a river in European Russia

*Don River (disambiguation), several other rivers with the name

*Don, Benin, a town in Benin

*Don, Dang, a vill ...

. The portages of what is now Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

were vital for the Varangian

The Varangians (; non, Væringjar; gkm, Βάραγγοι, ''Várangoi'';Varangian

" Online Etymo ...

commerce with the Orient and Byzantium.

At the most important portages (such as " Online Etymo ...

Gnezdovo

Gnezdovo or Gnyozdovo (russian: Гнёздово) is an archeological site located near the village of Gnyozdovo in Smolensky District, Smolensk Oblast, Russia. The site contains extensive remains of a Slavic-Varangian settlement that flourished ...

) there were trade outposts inhabited by a mixture of Norse merchants and native population. The Khazars

The Khazars ; he, כּוּזָרִים, Kūzārīm; la, Gazari, or ; zh, 突厥曷薩 ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a semi-nomadic Turkic people that in the late 6th-century CE established a major commercial empire coverin ...

built the fortress of Sarkel

Sarkel (or Šarkel, literally ''white house'' in the Khazar language was a large limestone-and-brick fortress in the present-day Rostov Oblast of Russia, on the left bank of the lower Don River.

It was built by the Khazars with Byzantine ass ...

to guard a key portage between the Volga and the Don. After Varangian and Khazar power in Eastern Europe waned, Slavic merchants continued to use the portages along the Volga trade route

In the Middle Ages, the Volga trade route connected Northern Europe and Northwestern Russia with the Caspian Sea and the Sasanian Empire, via the Volga River. The Rus used this route to trade with Muslim countries on the southern shores of the ...

and the Dnieper trade route

The trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks was a medieval trade route that connected Scandinavia, Kievan Rus' and the Eastern Roman Empire. The route allowed merchants along its length to establish a direct prosperous trade with the Empir ...

.

The names of the towns Volokolamsk

Volokolamsk (russian: Волокола́мск) is a town and the administrative center of Volokolamsky District in Moscow Oblast, Russia, located on the Gorodenka River, not far from its confluence with the Lama River, northwest of Moscow. Po ...

and Vyshny Volochek may be translated as "the portage on the Lama River

The Lama () is a river in the Moscow and Tver Oblasts in Russia, a tributary of the Shosha. The river is long. The area of its drainage basin is .Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

, meaning "portage", derived from the verb "to drag").

In the 16th century, the Russians used river portages to get to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

(see Cherdyn Road).

Scotland and Ireland

Tarbert is a common place name in Scotland and Ireland indicating the site of a portage.Africa

Portages played an important role in the economy of some African societies. For instance,Bamako

Bamako ( bm, ߓߡߊ߬ߞߐ߬ ''Bàmakɔ̌'', ff, 𞤄𞤢𞤥𞤢𞤳𞤮 ''Bamako'') is the capital and largest city of Mali, with a 2009 population of 1,810,366 and an estimated 2022 population of 2.81 million. It is located on the Niger Rive ...

was chosen as the capital of Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Mal ...

because it is located on the Niger River

The Niger River ( ; ) is the main river of West Africa, extending about . Its drainage basin is in area. Its source is in the Guinea Highlands in south-eastern Guinea near the Sierra Leone border. It runs in a crescent shape through ...

near the rapids that divide the Upper and Middle Niger Valleys.

North America

Places where portaging occurred often became temporary and then permanent settlements. The importance of free passage through portages found them included in laws and treaties. One historically important fur trade portage is nowGrand Portage National Monument

Grand Portage National Monument is a United States National Monument located on the north shore of Lake Superior in northeastern Minnesota that preserves a vital center of fur trade activity and Anishinaabeg Ojibwe heritage. The area became one ...

. Recreational canoeing routes often include portages between lakes, for example, the Seven Carries

The Seven Carries is an historic canoe route from Paul Smith's Hotel to the Saranac Inn through what is now known as the Saint Regis Canoe Area in southern Franklin County, New York in the Adirondack Park. The route was famous with sportsmen an ...

route in Adirondack Park

The Adirondack Park is a part of Forest Preserve (New York), New York's Forest Preserve in northeastern New York (state), New York, United States. The park was established in 1892 for “the free use of all the people for their health and pleasur ...

.

Numerous portages were upgraded to carriageways and railways due to their economic importance. The Niagara Portage had a gravity railway in the 1760s. The passage between the Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

and Des Plaines River

The Des Plaines River () is a river that flows southward for U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed May 13, 2011 through southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois''American Her ...

s was through a short swamp portage which seasonally flooded and it is thought that a channel gradually developed unintentionally from the dragging of the boat bottoms. The 1835 Champlain and St. Lawrence Railroad connected the cities of New York and Montreal without needing to go through the Atlantic.

Many settlements in North America were named for being on a portage.

Oceania

New Zealand

Portages existed in a number of locations where an isthmus existed that the local Māori could drag or carry theirwaka

Waka may refer to:

Culture and language

* Waka (canoe), a Polynesian word for canoe; especially, canoes of the Māori of New Zealand

** Waka ama, a Polynesian outrigger canoe

** Waka hourua, a Polynesian ocean-going canoe

** Waka taua, a Māori w ...

across from the Tasman Sea

The Tasman Sea ( Māori: ''Te Tai-o-Rēhua'', ) is a marginal sea of the South Pacific Ocean, situated between Australia and New Zealand. It measures about across and about from north to south. The sea was named after the Dutch explorer ...

to the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contin ...

or vice versa. The most famous ones are located in Auckland

Auckland (pronounced ) ( mi, Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in the North Island of New Zealand. The most populous urban area in the country and the fifth largest city in Oceania, Auckland has an urban population of about ...

, where there remain three roads named 'Portage Road's in separate parts of the city. Portage Road in the Auckland suburb of Ōtāhuhu

Ōtāhuhu is a suburb of Auckland, New Zealand – to the southeast of the CBD, on a narrow isthmus between an arm of the Manukau Harbour to the west and the Tamaki River estuary to the east. The isthmus is the narrowest connection between th ...

has historical plaques at both the north and south ends proclaiming it to be 'at half a mile in length, surely the shortest road between two seas'.

The small Marlborough Sounds settlement of Portage lies on the Kenepuru Sound

Kenepuru Sound is one of the larger of the Marlborough Sounds in the South Island of New Zealand. The drowned valley is an arm of Pelorus Sound / Te Hoiere, it runs for from the northeast to southwest, joining Pelorus Sound a quarter of the way ...

which links Queen Charlotte Sound at Torea Bay. This portage was created by mid-19th century settler Robert Blaymires.

See also

* Porter (carrier)References

{{Canoeing and kayaking Physical geography Water transport *