Pompey's Pillar (column) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pompey's Pillar ( ar, عمود السواري, translit='Amud El-Sawari) is the name given to a Roman triumphal column in

Pompey's Pillar ( ar, عمود السواري, translit='Amud El-Sawari) is the name given to a Roman triumphal column in

Searchable Greek Inscriptions

' of the

Muslim traveller

Muslim traveller

Pompey's Pillar ( ar, عمود السواري, translit='Amud El-Sawari) is the name given to a Roman triumphal column in

Pompey's Pillar ( ar, عمود السواري, translit='Amud El-Sawari) is the name given to a Roman triumphal column in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

. Set up in honour of the Roman emperor Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

between 298–302 AD, the giant Corinthian Corinthian or Corinthians may refer to:

*Several Pauline epistles, books of the New Testament of the Bible:

**First Epistle to the Corinthians

**Second Epistle to the Corinthians

**Third Epistle to the Corinthians (Orthodox)

*A demonym relating to ...

column originally supported a colossal porphyry statue of the emperor in armour. It stands at the eastern side of the ''temenos

A ''temenos'' (Greek: ; plural: , ''temenē''). is a piece of land cut off and assigned as an official domain, especially to kings and chiefs, or a piece of land marked off from common uses and dedicated to a god, such as a sanctuary, holy gro ...

'' of the Serapeum of Alexandria

The Serapeum of Alexandria in the Ptolemaic Kingdom was an ancient Greek temple built by Ptolemy III Euergetes (reigned 246–222 BC) and dedicated to Serapis, who was made the protector of Alexandria. There are also signs of Harpocrates. I ...

, beside the ruins of the temple of Serapis

Serapis or Sarapis is a Graeco-Egyptian deity. The cult of Serapis was promoted during the third century BC on the orders of Greek Pharaoh Ptolemy I Soter of the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt as a means to unify the Greeks and Egyptians in his r ...

itself.

It is the only ancient monument still standing in Alexandria in its original location today.

Name

The local name is ar, عمود السواري, translit='Amud El-Sawari, where the word 'Amud means "column". The name Sawari has been translated in many ways by scholars, including Severus (i.e. EmperorSeptimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa (Roman province), Africa. As a young man he advanced thro ...

).

The name of Pompey in relation to the pillar was used by many European writers in early modern times. The name is considered to stem from a historical misreading of the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

dedicatory inscription

Epigraphy () is the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the wr ...

on the base; the name ΠΟΥΠΛΙΟΣ ( grc, Πού̣π̣ �ιοςPouplios, label=none) was confused with ΠΟΜΠΗΙΟΣ ( grc, Πομπήιος, Pompeios, links=no).

Construction

In 297 Diocletian, '' Augustus'' since 284, campaigned in Egypt to suppress the revolt of the usurperDomitius Domitianus

Lucius Domitius Domitianus or, rarely, Domitian III, was a Roman usurper against Diocletian, who seized power for a short time in Egypt.

History

Nothing is known of the background and family of Domitianus. He may have served as prefect of Egyp ...

. After a long siege, Diocletian captured Alexandria and executed Domitianus's successor Aurelius Achilleus

Aurelius Achilleus ( 297–298 AD) was a rebel against the Roman emperor Diocletian in Egypt in 297 AD.

All literary sources name Achilleus as an imperial pretender and the leader of the rebellion, but numismatic and papyrological evidence attrib ...

in 298. In 302 the emperor returned to the city and inaugurated a state grain supply. The dedication of the column monument and its statue of Diocletian, describes Diocletian as ''polioúchos'' ( grc, πολιοῦχον Ἀλεξανδρείας, polioúchon Alexandreias, city-guardian-god ACC

ACC most often refers to:

* Atlantic Coast Conference, an NCAA Division I collegiate athletic conference located in the US

*American College of Cardiology, A US-based nonprofit medical association that bestows credentials upon cardiovascular spec ...

of Alexandria).. At Searchable Greek Inscriptions

' of the

Packard Humanities Institute

The Packard Humanities Institute (PHI) is a non-profit foundation, established in 1987, and located in Los Altos, California, which funds projects in a wide range of conservation concerns in the fields of archaeology, music, film preservation, an ...

. In the fourth century AD this designation also applied to Serapis, the male counterpart of Isis

Isis (; ''Ēse''; ; Meroitic: ''Wos'' 'a''or ''Wusa''; Phoenician: 𐤀𐤎, romanized: ʾs) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingd ...

in the pantheon instituted by the Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

rulers of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, the Ptolemies

The Ptolemaic dynasty (; grc, Πτολεμαῖοι, ''Ptolemaioi''), sometimes referred to as the Lagid dynasty (Λαγίδαι, ''Lagidae;'' after Ptolemy I's father, Lagus), was a Macedonian Greek royal dynasty which ruled the Ptolemaic K ...

. The sanctuary complex dedicated to Serapis in which the column was originally erected, the Serapeum, was built under King Ptolemy III Euergetes in the third century BC and probably rebuilt in the era of the second century AD emperor Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania B ...

after it sustained damage in the Kitos War

The Kitos War (115–117; he, מרד הגלויות, mered ha-galuyot, or ''mered ha-tfutzot''; "rebellion of the diaspora" la, Tumultus Iudaicus) was one of the major Jewish–Roman wars (66–136). The rebellions erupted in 115, when most ...

s; in the later fourth century AD it was considered by Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus (occasionally Anglicisation, anglicised as Ammian) (born , died 400) was a Roman soldier and historian who wrote the penultimate major historical account surviving from Ancient history, antiquity (preceding Procopius). His w ...

a marvel rivalled only by Rome's sanctuary to Jupiter ''Optimus Maximus'' on the Capitoline Hill, the Capitolium

A ''Capitolium'' (Latin) was an ancient Roman temple dedicated to the Capitoline Triad of gods Jupiter, Juno and Minerva. A capitolium was built on a prominent area in many cities in Italy and the Roman provinces, particularly during the Augus ...

.

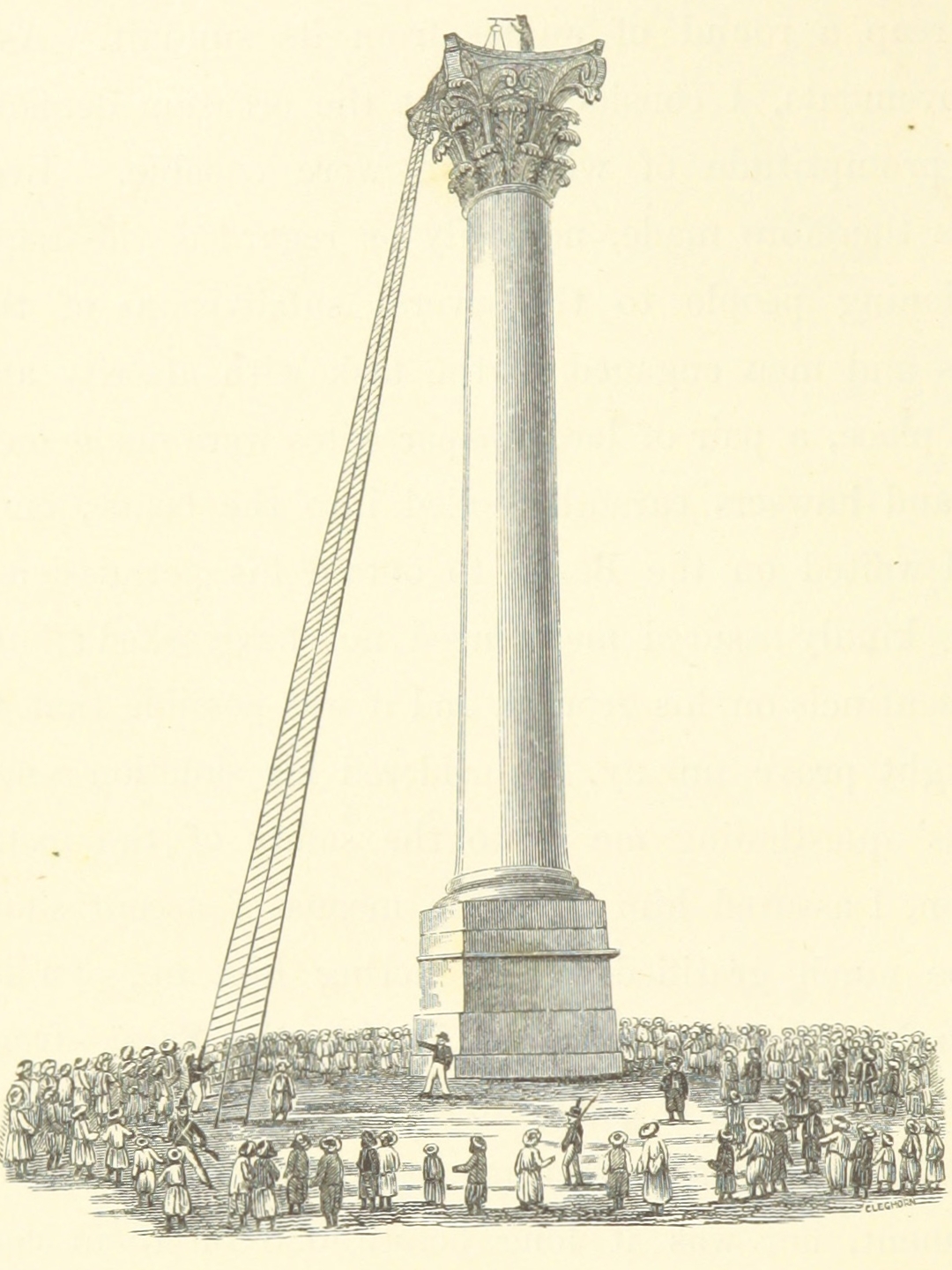

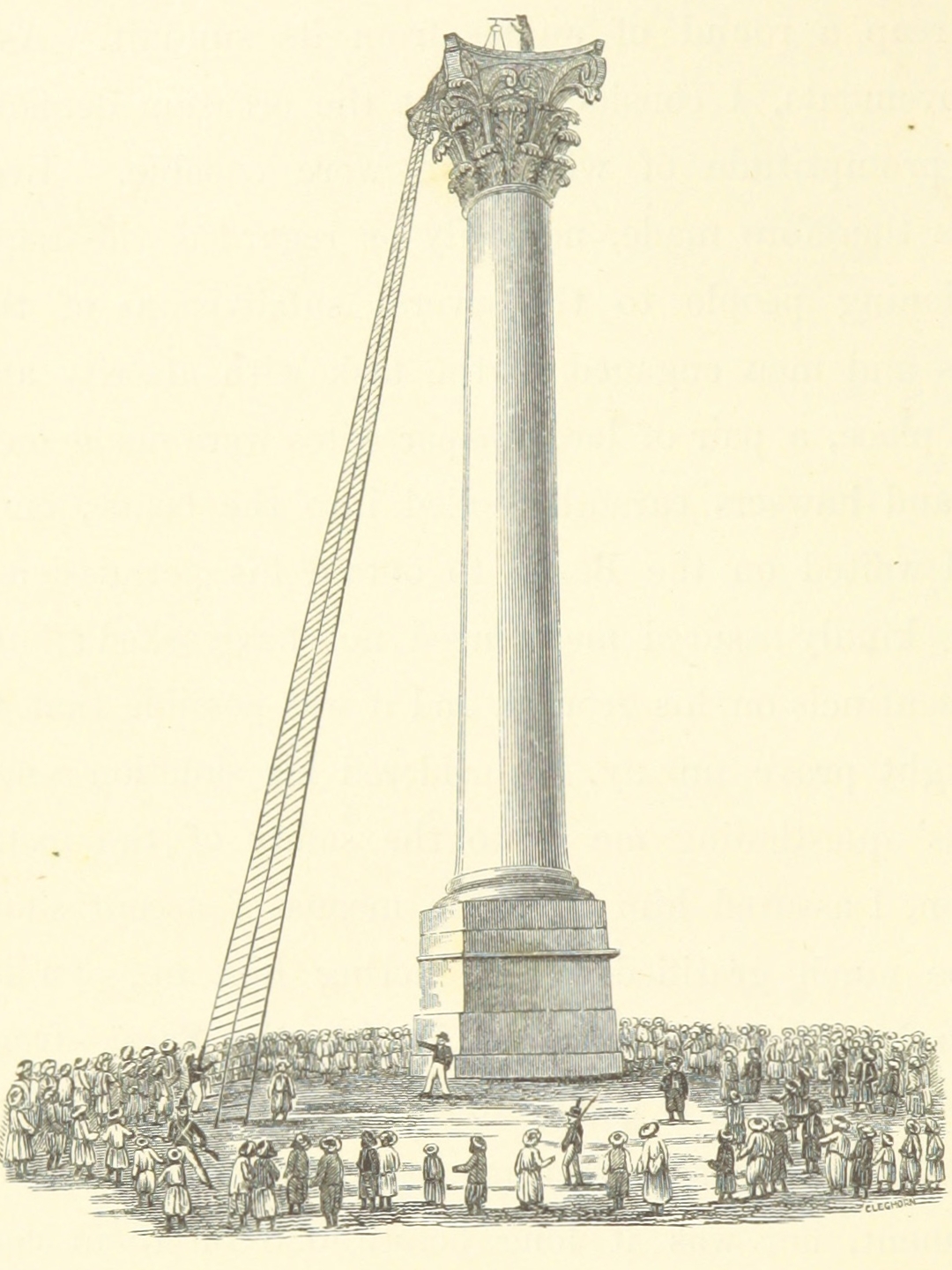

The monument stands some high, including its base and capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used f ...

, and originally would have supported a statue some tall. The only known monolithic column

A monolithic column or single-piece column is a large column of which the shaft is made from a single piece of stone instead of in vertical sections. Smaller columns are very often made from single pieces of stone, but are less often described a ...

in Roman Egypt

, conventional_long_name = Roman Egypt

, common_name = Egypt

, subdivision = Province

, nation = the Roman Empire

, era = Late antiquity

, capital = Alexandria

, title_leader = Praefectus Augustalis

, image_map = Roman E ...

(i.e., not composed of drums

A drum kit (also called a drum set, trap set, or simply drums) is a collection of drums, cymbals, and other Percussion instrument, auxiliary percussion instruments set up to be played by one person. The player (drummer) typically holds a pair o ...

), it is one of the largest ancient monoliths and one of the largest monolithic columns ever erected. The monolithic column shaft is in height with a diameter of at its base, and the socle itself is over tall. Both are of ''lapis syenites'', a pink granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies undergro ...

cut from the ancient quarries at Syene (modern Aswan

Aswan (, also ; ar, أسوان, ʾAswān ; cop, Ⲥⲟⲩⲁⲛ ) is a city in Southern Egypt, and is the capital of the Aswan Governorate.

Aswan is a busy market and tourist centre located just north of the Aswan Dam on the east bank of the ...

), while the column capital of pseudo-Corinthian type is of grey granite. The weight of the column shaft is estimated to be 285 tonne

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the short ton ( United State ...

s.

The surviving and readable four lines of the inscription in Greek on the column's socle relate that a ''Praefectus Aegypti

During the Roman Empire, the governor of Roman Egypt ''(praefectus Aegypti)'' was a prefect who administered the Roman province of Egypt with the delegated authority ''(imperium)'' of the emperor.

Egypt was established as a Roman province in con ...

'' ( grc, ἔπαρχος Αἰγύπτου, eparchos Aigyptou, Eparch

Eparchy ( gr, ἐπαρχία, la, eparchía / ''overlordship'') is an ecclesiastical unit in Eastern Christianity, that is equivalent to a diocese in Western Christianity. Eparchy is governed by an ''eparch'', who is a bishop. Depending on t ...

of Egypt, links=no) called Publius dedicated the monument in Diocletian's honour. A ''praefectus aegypti'' named Publius is attested in two papyri from Oxyrrhynchus; his governorship must have been held in between the prefectures of Aristius Optatus, who is named as governor on 16 March 297, and Clodius Culcianus, in office from 303 or even late 302. Since Publius's name appears as the monument's dedicator, the column and stylite statue of Diocletian must have been completed between 297 and 303, while he was in post. The governor's name is largely erased in the damaged inscription; the Greek rendering of Publius as ΠΟΥΠΛΙΟΣ ( grc, Πού̣π̣ �ιοςPouplios, label=none) was confused with the Greek spelling of the Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

general of the first century BC Pompey, ΠΟΜΠΗΙΟΣ ( grc, Πομπήιος, Pompeios, links=no, ).

The porphyry statue of Diocletian in armour is known from large fragments that existed at the column's foot in the eighteenth century AD. From the size of a fragment representing the thighs of the honorand, the original height of the loricate statue has been calculated at approximately . While some fragments of the statue were known to be in European collections in the nineteenth century, their whereabouts were unknown by the 1930s and are presumed lost.

It is possible that the large column supporting Diocletian's statue was accompanied by another column, or three smaller columns bearing statues of Diocletian's co-emperors, the ''Augustus'' Maximian

Maximian ( la, Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maximianus; c. 250 – c. July 310), nicknamed ''Herculius'', was Roman emperor from 286 to 305. He was ''Caesar'' from 285 to 286, then ''Augustus'' from 286 to 305. He shared the latter title with his ...

and the two ''Caesares'' Constantius and Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across the D ...

. If so, the group of column-statues would have commemorated the college of emperors of the Tetrarchy

The Tetrarchy was the system instituted by Roman emperor Diocletian in 293 AD to govern the ancient Roman Empire by dividing it between two emperors, the '' augusti'', and their juniors colleagues and designated successors, the '' caesares' ...

instituted in Diocletian's reign.

Ascents

Muslim traveller

Muslim traveller Ibn Battuta

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berbers, Berber Maghrebi people, Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, ...

visited Alexandria in 1326 AD. He describes the pillar and recounts the tale of an archer who shot an arrow tied to a string over the column. This enabled him to pull a rope tied to the string over the pillar and secure it on the other side in order to climb over to the top of the pillar.

In early 1803, British naval officer Commander John Shortland

John Shortland (5 September 1769 – 21 January 1810) was an officer of the Royal Navy, the eldest son of John Shortland.HMS ''Pandour'' flew a

File:View of Pompey's Pillar with Alexandria in the background in c.1850.jpg, View of Pompey's Pillar with Alexandria in the background in c.1850

File:Siege de la Colonne de Pompée.jpg, Siege de la Colonne de Pompée - Science in the pillory. 1799 cartoon, in which

kite

A kite is a tethered heavier than air flight, heavier-than-air or lighter-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create Lift (force), lift and Drag (physics), drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. ...

over Pompey's Pillar. This enabled him to get ropes over it, and then a rope ladder

A rope is a group of yarns, plies, fibres, or strands that are twisted or braided together into a larger and stronger form. Ropes have tensile strength and so can be used for dragging and lifting. Rope is thicker and stronger than similarly c ...

. On February 2, he and John White, ''Pandour''s Master, climbed it. When they got to the top they displayed the Union Jack

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

, drank a toast

Toast most commonly refers to:

* Toast (food), bread browned with dry heat

* Toast (honor), a ritual in which a drink is taken

Toast may also refer to:

Places

* Toast, North Carolina, a census-designated place in the United States

Books

* '' ...

to King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, and gave three cheers

Hip hip hooray (also hippity hip hooray; ''Hooray'' may also be spelled and pronounced hoorah, hurrah, hurray etc.) is a cheer called out to express congratulation toward someone or something, in the English-speaking world and elsewhere.

By a sol ...

. Four days later they climbed the pillar again, erected a staff, fixed a weather vane

A wind vane, weather vane, or weathercock is an instrument used for showing the direction of the wind. It is typically used as an architectural ornament to the highest point of a building. The word ''vane'' comes from the Old English word , m ...

, ate a beef steak, and again toasted the king. An etymology of the nickname "Pompey" for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

's home port of Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

and its football team

A football team is a group of players selected to play together in the various team sports known as football. Such teams could be selected to play in a match against an opposing team, to represent a football club, group, state or nation, an All-st ...

suggests these sailors became known as "Pompey's boys" after scaling the Pillar, and the moniker spread; other unrelated origins are also possible.

Gallery

James Gillray

James Gillray (13 August 1756Gillray, James and Draper Hill (1966). ''Fashionable contrasts''. Phaidon. p. 8.Baptism register for Fetter Lane (Moravian) confirms birth as 13 August 1756, baptism 17 August 1756 1June 1815) was a British caricatur ...

lampoons the corp of scientists, artists and architects that travelled to Egypt as part of Napoleon's force

File:Pompey's Pillar Greek Inscription.png, The Greek inscription

File:Pompey's Pillar Greek inscription 03.png, 1743 version

File:Pompey's Pillar Greek inscription 02.png, 1803 version

File:Pompey's Pillar Greek inscription 01.png, 1822 version

See also

*List of ancient architectural records

This is the list of ancient architectural records consists of record-making architectural achievements of the Greco-Roman world from c. 800 BC to 600 AD.

Bridges

*The highest bridge over the water or ground was the single-arched ...

* Browne-Clayton Monument

The Browne-Clayton Monument is a column of the Corinthian order on a square pedestal base built in the 19th-century in Leinster, Ireland. It stands on Carrigadaggan Hill, at Carrigbyrne in County Wexford at , just off the N25 national route be ...

* Pompey's Pillar (disambiguation), listing other things named for this pillar

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * {{Commons category, Pompey's Pillar, Alexandria, Pompey's Pillar Buildings and structures completed in the 3rd century Buildings and structures in Alexandria Roman victory columns Corinthian columns Monoliths