Polyclonal B cell response is a natural mode of immune response exhibited by the

adaptive immune system

The adaptive immune system, also known as the acquired immune system, is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized, systemic cells and processes that eliminate pathogens or prevent their growth. The acquired immune system ...

of

mammals

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fu ...

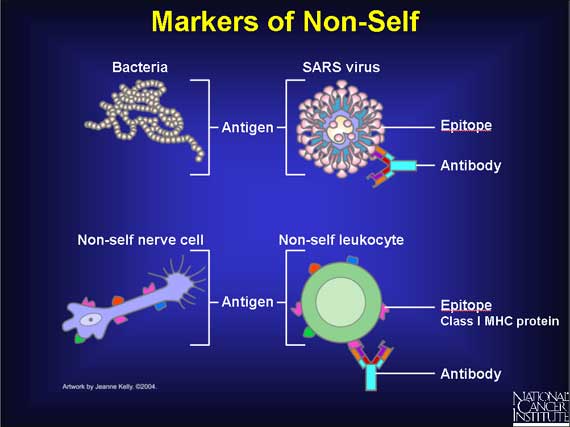

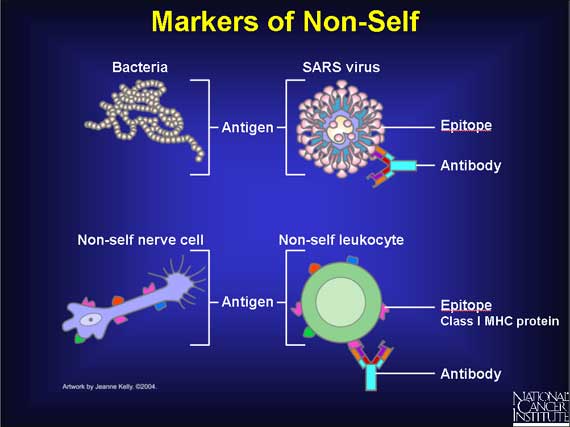

. It ensures that a single

antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

is recognized and attacked through its overlapping parts, called

epitope

An epitope, also known as antigenic determinant, is the part of an antigen that is recognized by the immune system, specifically by antibodies, B cells, or T cells. The epitope is the specific piece of the antigen to which an antibody binds. The ...

s, by multiple

clones of

B cell

B cells, also known as B lymphocytes, are a type of white blood cell of the lymphocyte subtype. They function in the humoral immunity component of the adaptive immune system. B cells produce antibody molecules which may be either secreted or ...

.

In the course of normal immune response, parts of

pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a ger ...

s (e.g.

bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

) are recognized by the immune system as foreign (non-self), and eliminated or effectively neutralized to reduce their potential damage. Such a recognizable substance is called an

antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

. The immune system may respond in multiple ways to an antigen; a key feature of this response is the production of

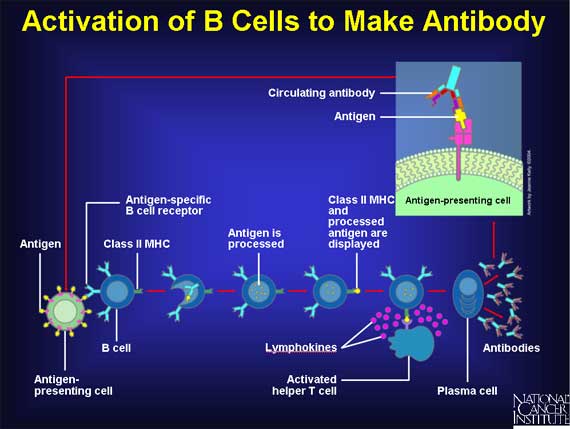

antibodies by B cells (or B lymphocytes) involving an arm of the immune system known as

humoral immunity

Humoral immunity is the aspect of immunity that is mediated by macromolecules - including secreted antibodies, complement proteins, and certain antimicrobial peptides - located in extracellular fluids. Humoral immunity is named so because it ...

. The antibodies are soluble and do not require direct cell-to-cell contact between the pathogen and the B-cell to function.

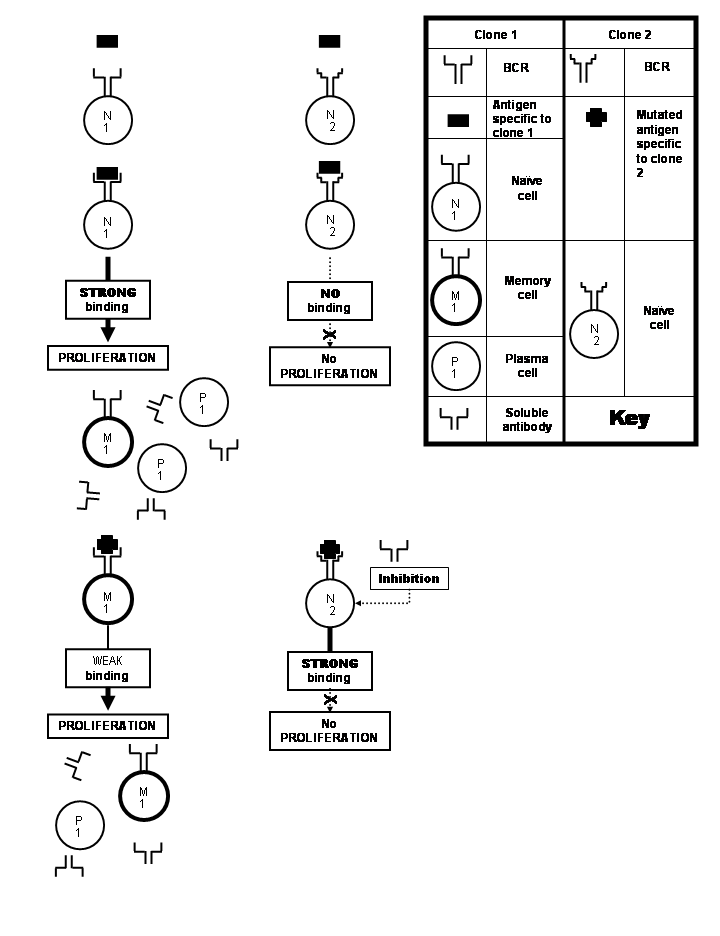

Antigens can be large and complex substances, and any single antibody can only bind to a small, specific area on the antigen. Consequently, an effective immune response often involves the production of many different antibodies by many different B cells against the ''same'' antigen. Hence the term "polyclonal", which derives from the words ''poly'', meaning many, and ''clones'' from Greek ''klōn'', meaning sprout or twig;

a clone is a group of cells arising from a common "mother" cell. The antibodies thus produced in a polyclonal response are known as

polyclonal antibodies

Polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) are antibodies that are secreted by different B cell lineages within the body (whereas monoclonal antibodies come from a single cell lineage). They are a collection of immunoglobulin molecules that react against a sp ...

. The

heterogeneous

Homogeneity and heterogeneity are concepts often used in the sciences and statistics relating to the uniformity of a substance or organism. A material or image that is homogeneous is uniform in composition or character (i.e. color, shape, siz ...

polyclonal antibodies are distinct from

monoclonal antibody

A monoclonal antibody (mAb, more rarely called moAb) is an antibody produced from a cell Lineage made by cloning a unique white blood cell. All subsequent antibodies derived this way trace back to a unique parent cell.

Monoclonal antibodies ...

molecules, which are identical and react against a single epitope only, i.e., are more specific.

Although the polyclonal response confers advantages on the immune system, in particular, greater probability of reacting against pathogens, it also increases chances of developing certain autoimmune diseases resulting from the reaction of the immune system against native molecules produced within the host.

Humoral response to infection

Diseases which can be transmitted from one organism to another are known as

infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable d ...

s, and the causative biological agent involved is known as a

pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a ger ...

. The process by which the pathogen is introduced into the body is known as

inoculation,

[The term ''"inoculation"'' is usually used in context of ]active immunization

Active immunization is the induction of immunity after exposure to an antigen. Antibodies are created by the recipient and may be stored permanently.

Active immunization can occur naturally when microbes or other antigen are received by a person ...

, i.e., deliberately introducing the antigenic substance into the host's body. But in many discussions of infectious diseases, it is not uncommon to use the term to imply a spontaneous (that is, without human intervention) event resulting in introduction of the causative organism into the body, say ingesting water contaminated with Salmonella typhi

''Salmonella enterica'' subsp. ''enterica'' is a subspecies of ''Salmonella enterica'', the rod-shaped, flagellated, aerobic, Gram-negative bacterium. Many of the pathogenic serovars of the ''S. enterica'' species are in this subspecies, includ ...

—the causative organism for typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over severa ...

. In such cases the causative organism itself is known as the ''inoculum'', and the number of organisms introduced as the "dose of inoculum". and the organism it affects is known as a

biological host. When the pathogen establishes itself in a step known as

colonization

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

,

[

] it can result in an

infection

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable d ...

,

consequently harming the host directly or through the harmful substances called

toxin

A toxin is a naturally occurring organic poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. Toxins occur especially as a protein or conjugated protein. The term toxin was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849 ...

s it can produce.

This results in the various

symptom

Signs and symptoms are the observed or detectable signs, and experienced symptoms of an illness, injury, or condition. A sign for example may be a higher or lower temperature than normal, raised or lowered blood pressure or an abnormality showi ...

s and

signs

Signs may refer to:

* ''Signs'' (2002 film), a 2002 film by M. Night Shyamalan

* ''Signs'' (TV series) (Polish: ''Znaki'') is a 2018 Polish-language television series

* ''Signs'' (journal), a journal of women's studies

*Signs (band), an American ...

characteristic of an infectious disease like

pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severi ...

or

diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild clinical course, but in some outbreaks more than 10% of those diagnosed with the disease may die. Signs and s ...

.

Countering the various infectious diseases is very important for the survival of the

susceptible

Susceptibility may refer to:

Physics and engineering

In physics the susceptibility is a quantification for the change of an extensive property under variation of an intensive property. The word may refer to:

* In physics, the susceptibility of ...

organism, in particular, and the species, in general. This is achieved by the host by eliminating the pathogen and its toxins or rendering them nonfunctional. The collection of various

cells,

tissues and

organs that specializes in protecting the body against infections is known as the

immune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as Tumor immunology, cancer cells and objects such ...

. The immune system accomplishes this through direct contact of certain

white blood cell

White blood cells, also called leukocytes or leucocytes, are the cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign invaders. All white blood cells are produced and derived from mult ...

s with the invading pathogen involving an arm of the immune system known as the

cell-mediated immunity

Cell-mediated immunity or cellular immunity is an immune response that does not involve antibodies. Rather, cell-mediated immunity is the activation of phagocytes, antigen-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes, and the release of various cytokines ...

, or by producing substances that move to sites ''distant'' from where they are produced, "seek" the disease-causing cells and toxins by specifically

[''Specificity'' implies that two different pathogens will be actually viewed as two distinct entities, and countered by different antibody molecules.] binding with them, and neutralize them in the process–known as the

humoral arm of the immune system. Such substances are known as soluble antibodies and perform important functions in countering infections.

[Actions of antibodies:

* Coating the pathogen, preventing it from adhering to the host cell, and thus preventing colonization

* Precipitating (making the particles "sink" by attaching to them) the soluble antigens and promoting their clearance by other cells of immune system from the various tissues and blood

* Coating the microorganisms to attract cells that can engulf the pathogen. This is known as ]opsonization

Opsonins are extracellular proteins that, when bound to substances or cells, induce phagocytes to phagocytose the substances or cells with the opsonins bound. Thus, opsonins act as tags to label things in the body that should be phagocytosed (i.e. ...

. Thus the antibody acts as an ''opsonin''. The process of engulfing is known as phagocytosis

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs phagocytosis i ...

(literally, ''cell eating'')

* Activating the complement system

The complement system, also known as complement cascade, is a part of the immune system that enhances (complements) the ability of antibodies and phagocytic cells to clear microbes and damaged cells from an organism, promote inflammation, and ...

, which most importantly pokes holes into the pathogen's outer covering (its cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment (the ...

), killing it in the process

* Marking up host cells infected by viruses for destruction in a process known as Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity

Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), also referred to as antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, is a mechanism of cell-mediated immune defense whereby an effector cell of the immune system actively lyses a target cell, whose ...

(ADCC)

in protecting the host against the pathogen. Their soluble forms which carry out these functions are produced by

s, a type of white blood cell. This production is tightly regulated and requires the activation of B cells by activated

s (another type of white blood cell), which is a sequential procedure. The major steps involved are:

*Specific or nonspecific recognition of the pathogen (because of its antigens) with its subsequent engulfing by B cells or

s. This activates the B cell only ''partially''.

*

of the B cell by ''activated'' T cell resulting in its ''complete'' activation.

*

of B cells with resultant production of soluble antibodies.

"'' antigens; they may express the molecules on their surface or release them into the surroundings (body fluids). What makes these substances recognizable is that they bind very specifically and somewhat strongly to certain host proteins called ''

''. The same antibodies can be anchored to the surface of cells of the immune system, in which case they serve as

, or they can be secreted in the blood, known as soluble antibodies. On a molecular scale, the proteins are relatively large, so they cannot be recognized as a whole; instead, their segments, called

s, can be recognized.

Polyclonal B cell response is a natural mode of immune response exhibited by the

Polyclonal B cell response is a natural mode of immune response exhibited by the

A single antigen can be thought of as a sequence of multiple overlapping epitopes. Many unique B cell clones may be able to bind to the individual epitopes. This imparts even greater multiplicity to the overall response. All of these B cells can become activated and produce large colonies of plasma cell clones, each of which can secrete up to 1000 antibody molecules against each epitope per second.

A single antigen can be thought of as a sequence of multiple overlapping epitopes. Many unique B cell clones may be able to bind to the individual epitopes. This imparts even greater multiplicity to the overall response. All of these B cells can become activated and produce large colonies of plasma cell clones, each of which can secrete up to 1000 antibody molecules against each epitope per second.

Many viruses undergo frequent

Many viruses undergo frequent