Polonophilia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A Polonophile is an individual who respects and is fond of Poland's culture as well as Polish history, traditions and customs. The term defining this kind of attitude is Polonophilia. The

A Polonophile is an individual who respects and is fond of Poland's culture as well as Polish history, traditions and customs. The term defining this kind of attitude is Polonophilia. The

When Polish King

When Polish King  During the PolishãLithuanian Commonwealth, the

During the PolishãLithuanian Commonwealth, the

The Partitions of Poland, Partitions, which arguably occurred because of Poland's previous conquests, gave a rise to a new wave of Polonophilia in Europe and the world. Exiled revolutionaries such as Casimir Pulaski and Tadeusz Koéciuszko, who fought for the independence of the United States from Great Britain, contributed to the sentiment that is relatively pro-Polish in

The Partitions of Poland, Partitions, which arguably occurred because of Poland's previous conquests, gave a rise to a new wave of Polonophilia in Europe and the world. Exiled revolutionaries such as Casimir Pulaski and Tadeusz Koéciuszko, who fought for the independence of the United States from Great Britain, contributed to the sentiment that is relatively pro-Polish in  One of the most prominent and self-declared Polonophiles of the late 19th century was the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who was certain of his Polish heritage. He often expressed his positive views and admiration towards Poles and their culture. However, modern scholars believe that Nietzsche's claim of Polish ancestry was a pure invention. According to biographer

One of the most prominent and self-declared Polonophiles of the late 19th century was the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who was certain of his Polish heritage. He often expressed his positive views and admiration towards Poles and their culture. However, modern scholars believe that Nietzsche's claim of Polish ancestry was a pure invention. According to biographer

One of the regions that demonstrated its Polish identity was the ethnic Silesian minority in Upper Silesia, which was subjected to systematic

One of the regions that demonstrated its Polish identity was the ethnic Silesian minority in Upper Silesia, which was subjected to systematic

Many

Many

During the Second World War, Hungary refused to allow Adolf Hitler's troops to pass through the country during the invasion of Poland in September 1939. Although Hungary, which was ruled by Miklû°s Horthy, was allied with Nazi Germany, it declined to participate in the invasion as a matter of "Hungarian honour".

On 12 March 2007, the Hungarian Parliament declared 23 March as the "Day of Hungarian-Polish Friendship", with 324 votes in favor, none opposed, and no abstentions. Four days later, the Polish Parliament declared 23 March as the "Day of Polish-Hungarian Friendship" by acclamation. The Hungarian Parliament also voted 2016 as the Year of Hungarian-Polish solidarity.

The Hungarian-born Prince Stephen BûÀthory was elected

During the Second World War, Hungary refused to allow Adolf Hitler's troops to pass through the country during the invasion of Poland in September 1939. Although Hungary, which was ruled by Miklû°s Horthy, was allied with Nazi Germany, it declined to participate in the invasion as a matter of "Hungarian honour".

On 12 March 2007, the Hungarian Parliament declared 23 March as the "Day of Hungarian-Polish Friendship", with 324 votes in favor, none opposed, and no abstentions. Four days later, the Polish Parliament declared 23 March as the "Day of Polish-Hungarian Friendship" by acclamation. The Hungarian Parliament also voted 2016 as the Year of Hungarian-Polish solidarity.

The Hungarian-born Prince Stephen BûÀthory was elected

Strong support for Poland and pro-Polish sentiment were also observed by US President Woodrow Wilson. In 1918, delivered his Fourteen Points as peace settlement to end World War I and stated in Point 13 that "an independent Polish state should be erected... with a free and secure access to the sea...".

US President Donald Trump also expressed his sentiment towards Poland and Polish history in his

Strong support for Poland and pro-Polish sentiment were also observed by US President Woodrow Wilson. In 1918, delivered his Fourteen Points as peace settlement to end World War I and stated in Point 13 that "an independent Polish state should be erected... with a free and secure access to the sea...".

US President Donald Trump also expressed his sentiment towards Poland and Polish history in his

A Polonophile is an individual who respects and is fond of Poland's culture as well as Polish history, traditions and customs. The term defining this kind of attitude is Polonophilia. The

A Polonophile is an individual who respects and is fond of Poland's culture as well as Polish history, traditions and customs. The term defining this kind of attitude is Polonophilia. The antonym

In lexical semantics, opposites are words lying in an inherently incompatible binary relationship. For example, something that is ''long'' entails that it is not ''short''. It is referred to as a 'binary' relationship because there are two members ...

and opposite of Polonophilia is Polonophobia.

History

Duchy and Kingdom of Poland

The history of the concept dates back to the beginning of the Polish state in 966 AD under DukeMieszko I

Mieszko I (; ã 25 May 992) was the first ruler of Poland and the founder of the first independent Polish state, the Duchy of Poland. His reign stretched from 960 to his death and he was a member of the Piast dynasty, a son of Siemomysé and ...

. It remained strong among ethnic minorities as in allied neighbouring countries and during Polonization of the Eastern Borderlands, Livonia, Silesia and other acquired territories implied by the Polish Crown or the Polish government, thus also triggering Polonophobia.

One of the first recorded potential Polonophiles were exiled Jews, who settled in Poland throughout the Middle Ages, particularly following the First Crusade (1096-1099). The culture and the intellectual output of the Jewish community in Poland had a profound impact on Judaism as a whole over the next centuries, with both cultures becoming somewhat interconnected and being influenced by each other. Jewish historians claimed that the name of the country is pronounced as "Polania" or "Polin" in Hebrew, which was interpreted as a good omen because Polania can be divided into three separate Hebrew words: ''po'' (here), ''lan'' (dwells), ''ya'' (God) and Polin into two words: ''po'' (here) ''lin'' (ou should

OU or Ou or ou may stand for:

Universities United States

* Oakland University in Oakland County, Michigan

* Oakwood University in Huntsville, Alabama

* Oglethorpe University in Atlanta, Georgia

* Ohio University in Athens, Ohio

* Olivet Universi ...

dwell). Thar suggested that Poland was a good destination for the Jews fleeing from persecution and anti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

in other European countries. Rabbi David HaLevi Segal

David ha-Levi Segal (c. 1586 – 20 February 1667), also known as the Turei Zahav (abbreviated Taz ()) after the title of his significant ''halakhic'' commentary on the ''Shulchan Aruch'', was one of the greatest Polish rabbinical authorities.

...

(Taz) expressed his pro-Polish views by stating in Poland, "most of the time the Gentiles do no harm; on the contrary they do right by Israel" (Divre David; 1689). Ashkenazi Jews willingly adopted some aspects of Polish cuisine, language and national dress, which can be seen in Orthodox Jewish communities around the world.

PolishãLithuanian Commonwealth

Stephen Bathory

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, öÈüöÙüöÝö§ö¢ü ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; ...

captured Livonia (Truce of Jam Zapolski

The Truce or Treaty of Yam-Zapolsky (Å₤Å¥-ÅůŢŃţîſ) or Jam Zapolski, signed on 15 January 1582 between the PolishãLithuanian Commonwealth and the Tsardom of Russia, was one of the treaties that ended the Livonian War. It followed t ...

), he granted the city of Tartu

Tartu is the second largest city in Estonia after the Northern European country's political and financial capital, Tallinn. Tartu has a population of 91,407 (as of 2021). It is southeast of Tallinn and 245 kilometres (152 miles) northeast of ...

(Polish: ''Dorpat''), now in Estonia, its own banner with the colours and layout resembling the Polish flag

The national flag of Poland ( pl, flaga Polski) consists of two horizontal stripes of equal width, the upper one white and the lower one red. The two colours are defined in the Polish constitution as the national colours. A variant of the flag ...

. The flag dates from 1584 and is still in use.

When the Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Ce ...

invaded

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

the Tsardom of Russia in 1605, a self-identified prince, known as False Dmitry I, assumed the Russian throne. A Polonophile, he assured that King Sigismund III of Poland

Sigismund III Vasa ( pl, Zygmunt III Waza, lt, é§ygimantas Vaza; 20 June 1566 ã 30 April 1632

N.S.) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1587 to 1632 and, as Sigismund, King of Sweden and Grand Duke of Finland from 1592 to ...

could control the country's internal and external affairs, secure Russia's conversion to Catholicism and thus make it a puppet state. Dmitry's murder was a possible justification for arranging a full-scale invasion by Sigismund in 1609. The Seven Boyars deposed reigning Tsar Boris Godunov

BorûÙs Fyodorovich Godunû°v (; russian: ÅŃîÅ¡î ÅÊîÅÇŃîŃÅýÅ¡î ÅŃÅÇîŧŃÅý; 1552 ) ruled the Tsardom of Russia as ''de facto'' regent from c. 1585 to 1598 and then as the first non-Rurikid tsar from 1598 to 1605. After the end of his ...

to demonstrate their support for the Polish cause. Godunov was transported as a prisoner to Poland, where he died. In 1610, the Boyars elected Sigismund's underage son Wéadyséaw as the new Tsar of Russia, but he was never crowned. This period was known as the Time of Troubles, a major part in Russian history that remains relatively unmentioned in Polish historiography because of its implied Polonization policies.

During the PolishãLithuanian Commonwealth, the

During the PolishãLithuanian Commonwealth, the Zaporizhian Cossack

The Zaporozhian Cossacks, Zaporozhian Cossack Army, Zaporozhian Host, (, or uk, ÅîÅ¿îîŤŃ ÅůŢŃîîÅñîŤÅç, translit=Viisko Zaporizke, translit-std=ungegn, label=none) or simply Zaporozhians ( uk, ÅůŢŃîŃÅÑîî, translit=Zaporoz ...

state was allied to the Catholic King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16t ...

, and the Cossacks were often hired as mercenaries

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any o ...

. That had a strong impact on the Ukrainian language and led to the establishment of a functioning Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in 1596 at the Union of Brest. The Ukrainians, however, retained their Orthodox Christian

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Churche ...

faith and Cyrillic alphabet. During the Russo-Polish War of 1654ã1667, the Cossacks were divided into the pro-Polish ( Right-bank Ukraine) and pro-Russian ( Left-bank Ukraine) factions. Petro Doroshenko, who commanded the army of Right-bank Ukraine, and Pavlo Teteria and Ivan Vyhovsky

Ivan Vyhovsky ( uk, ÅÅýůŧ ÅšŰŃÅýîſ; pl, Iwan Wyhowski / Jan Wyhowski; date of birth unknown, died 1664), a Ukrainian military and political figure and statesman, served as hetman of the Zaporizhian Host and of the Cossack Hetma ...

were open Polonophiles and allied to the Polish king. The Polish influence on Ukraine ended with the partitions of the late 18th century, when the territory of contemporary Ukraine was annexed by the Russian Empire.

Under John III Sobieski

John III Sobieski ( pl, Jan III Sobieski; lt, Jonas III Sobieskis; la, Ioannes III Sobiscius; 17 August 1629 ã 17 June 1696) was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1674 until his death in 1696.

Born into Polish nobility, Sobie ...

, the Christian coalition forces defeated the Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, OsmanláÝ Tû¥rkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302ã1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

at the Battle of Vienna

The Battle of Vienna; pl, odsiecz wiedeéska, lit=Relief of Vienna or ''bitwa pod Wiedniem''; ota, BeûÏ Ã¡ýalò¢asáÝ MuáËáÿÈarasáÝ, lit=siege of BeûÏ; tr, á¯kinci Viyana KuéatmasáÝ, lit=second siege of Vienna took place at Kahlenberg Mou ...

in 1683, which ironically sparked admiration for Poland and its Winged Hussars in the Ottoman Empire. The Sultan

Sultan (; ar, Ä°ìÄñÄÏì ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

named Sobieski the "Lion of Lehistan

The ethnonyms for the Poles (people) and Poland (their country) include endonyms (the way Polish people refer to themselves and their country) and exonyms (the way other peoples refer to the Poles and their country). Endonyms and most exonyms ...

oland. That tradition was cultivated when Poland disappeared from map for 123 years. The Ottoman Empire, along with Persia, was the only major country in the world not to recognise the Partitions of Poland. The reception ceremony of a foreign ambassador or a diplomatic mission in Istanbul began with an announcement sacred formula: "the Ambassador of Lehistan olandhas not yet arrived".

After Partitions

The Partitions of Poland, Partitions, which arguably occurred because of Poland's previous conquests, gave a rise to a new wave of Polonophilia in Europe and the world. Exiled revolutionaries such as Casimir Pulaski and Tadeusz Koéciuszko, who fought for the independence of the United States from Great Britain, contributed to the sentiment that is relatively pro-Polish in

The Partitions of Poland, Partitions, which arguably occurred because of Poland's previous conquests, gave a rise to a new wave of Polonophilia in Europe and the world. Exiled revolutionaries such as Casimir Pulaski and Tadeusz Koéciuszko, who fought for the independence of the United States from Great Britain, contributed to the sentiment that is relatively pro-Polish in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

.

When Belgium declared independence from the Netherlands, Belgian diplomats refused to establish diplomatic relations with the Russian Empire for annexing a large portion of Poland's eastern territories during the Partitions. Diplomatic relations between Moscow and Brussels were established only decades later.

The November Uprising

The November Uprising (1830ã31), also known as the PolishãRussian War 1830ã31 or the Cadet Revolution,

was an armed rebellion in the heartland of partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. The uprising began on 29 November 1830 in W ...

in Congress Poland in 1830 against Russia prompted a wave of Polonophilia in Germany, including financial contributions to exiles, the singing of pro-Polish songs, and pro-Polish literature. During the January uprising

The January Uprising ( pl, powstanie styczniowe; lt, 1863 meté° sukilimas; ua, ÅÀîîŧÅçÅýÅç ŢŃÅýîîůŧŧî; russian: ÅŃţîîŤŃÅç ÅýŃîîîůŧšÅç; ) was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at ...

in 1863, however, the Polonophile sentiment had mostly vanished.

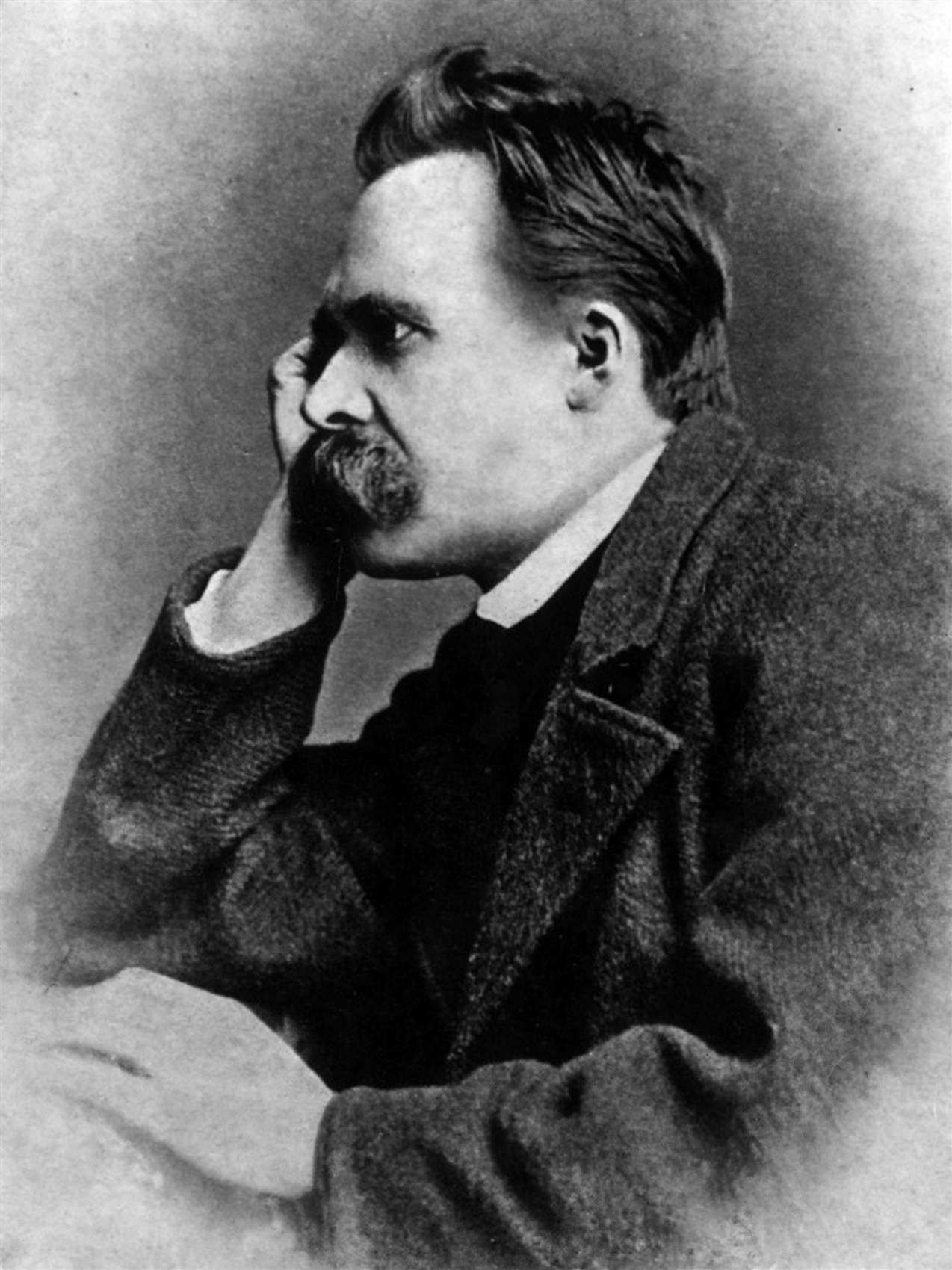

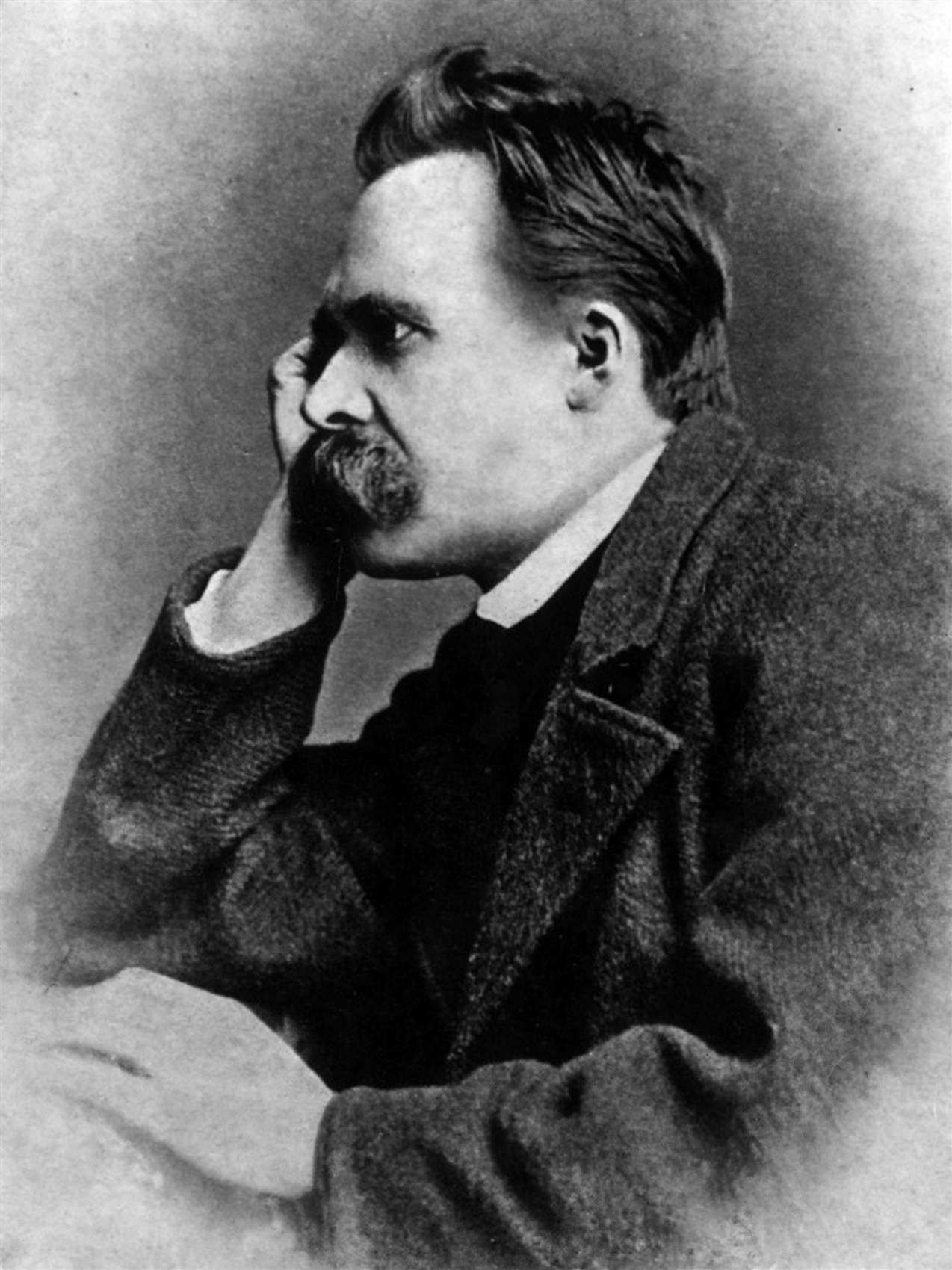

One of the most prominent and self-declared Polonophiles of the late 19th century was the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who was certain of his Polish heritage. He often expressed his positive views and admiration towards Poles and their culture. However, modern scholars believe that Nietzsche's claim of Polish ancestry was a pure invention. According to biographer

One of the most prominent and self-declared Polonophiles of the late 19th century was the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who was certain of his Polish heritage. He often expressed his positive views and admiration towards Poles and their culture. However, modern scholars believe that Nietzsche's claim of Polish ancestry was a pure invention. According to biographer R. J. Hollingdale

Reginald John "R. J." Hollingdale (20 October 1930 ã 28 September 2001) was a British biographer and translator of German philosophy and literature, especially the works of Friedrich Nietzsche, Goethe, E. T. A. Hoffmann, G. C. Lichtenberg, and ...

, Nietzsche's propagation of the Polish ancestry myth may have been part of his "campaign against Germany".

One of the strongest centres of Polonophilia in 19th-century Europe was Ireland. The Young Ireland movement and the Fenians saw similarities in both countries as "Catholic nations and victims of larger imperial powers". In 1863, Irish newspapers expressed wide support for the January uprising

The January Uprising ( pl, powstanie styczniowe; lt, 1863 meté° sukilimas; ua, ÅÀîîŧÅçÅýÅç ŢŃÅýîîůŧŧî; russian: ÅŃţîîŤŃÅç ÅýŃîîîůŧšÅç; ) was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at ...

, which was then seen as a risky move.

Throughout modern history, France was long Poland's ally, especially after French King Louis XV married Polish Princess Marie Leszczyéska, the daughter of Stanislaus I. Polish customs and fashion became popular in the Versailles such as the Polonaise dress (''robe û la polonaise''), which was adored by Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette Josû´phe Jeanne (; ; nûˋe Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2 November 1755 ã 16 October 1793) was the last queen of France before the French Revolution. She was born an archduchess of Austria, and was the penultimate child a ...

. Polish cuisine and also became known in French as ''û la polonaise''. Both Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 ã 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

and Napoleon III expressed strong pro-Polish sentiment after Poland had ceased to exist as a sovereign country in 1795. In 1807, Napoleon I established the Duchy of Warsaw, a client state of the French Empire

French Empire (french: Empire FranûÏais, link=no) may refer to:

* First French Empire, ruled by Napoleon I from 1804 to 1814 and in 1815 and by Napoleon II in 1815, the French state from 1804 to 1814 and in 1815

* Second French Empire, led by Nap ...

that was dissolved in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna. Napoleon III also called for a free Poland and his wife, Eugûˋnie de Montijo

''DoûÝa'' MarûÙa Eugenia Ignacia Agustina de Palafox y Kirkpatrick, 19th Countess of Teba, 16th Marchioness of Ardales (5 May 1826 ã 11 July 1920), known as Eugûˋnie de Montijo (), was Empress of the French from her marriage to Emperor Napo ...

, astonished the Austrian ambassador (Austria was one of three partitioning powers) by "unveiling a European map with a realignment of borders to accommodate independent Poland".

When Poland finally regained its independence following World War I, Polonophilia gradually transformed into a demonstration of patriotism

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and sense of attachment to one's country. This attachment can be a combination of many different feelings, language relating to one's own homeland, including ethnic, cultural, political or histor ...

and solidarity, especially during the horrors of the Second World War and the Polish struggle against communism.

Silesia

One of the regions that demonstrated its Polish identity was the ethnic Silesian minority in Upper Silesia, which was subjected to systematic

One of the regions that demonstrated its Polish identity was the ethnic Silesian minority in Upper Silesia, which was subjected to systematic Germanisation

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, German people, people and German culture, culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationa ...

and conversion to Protestantism under the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire ã particularly a hereditary ...

. After the Polish nation state was founded in 1918, Germany's Regency of Oppeln ( Upper Silesia) rebelled in solidarity with the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 1918 and 1939. The state was established on 6 November 1918, before the end of ...

in what became known as the Silesian uprisings. An eastern sliver of the region became part of the Polish Republic in 1922, and the Polish government had decided to grant the German territory autonomy in 1919 with the Silesian Parliament

Silesian Parliament or Silesian Sejm ( pl, Sejm élá

ski) was the governing body of the Silesian Voivodeship (1920ã1939), an autonomous voivodeship of the Second Polish Republic between 1920 and 1945. It was elected in democratic elections and ...

as a legislative and the Silesian Voivodeship Council as the executive body.

After the Second World War II, the whole of Upper Silesia and German Lower Silesia were assigned to Poland in accordance with the Potsdam Agreement

The Potsdam Agreement (german: Potsdamer Abkommen) was the agreement between three of the Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union on 1 August 1945. A product of the Potsdam Conference, it concerned th ...

. Expulsions and forced Polonization followed.

However, some Silesians still identify as Polish or German citizens, cultivate their Catholic traditions and preserve their unique and separate identity.

Contemporary

Armenia

Armenians in Poland have an important and historical presence which dates back to the 14th century, however, the first Armenian settlers arrived in the 12th century, which makes them the oldest minority in Poland with the Jews. A very significant and independent Armenian diaspora existed in Poland but was assimilated over the centuries because of Polonization and the absorption ofPolish culture

The culture of Poland ( pl, Kultura Polski ) is the product of its geography and distinct historical evolution, which is closely connected to an intricate thousand-year history. Polish culture forms an important part of western civilization and ...

. Between 40,000 and 80,000 people in Poland today claim Armenian nationality or Armenian heritage. Mass waves of Armenian immigration to Poland has occurred since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Armenians are highly fond of Polish culture and history. Several Armenian cultural features also exist in the Polish national dress, most notably the Karabela sabre introduced by Armenian merchants under Poland-Lithuania.

Georgia

Many

Many Georgians

The Georgians, or Kartvelians (; ka, ÃËÃÃ ÃÃÃÃÃÃÃ, tr, ), are a nation and indigenous Caucasian ethnic group native to Georgia and the South Caucasus. Georgian diaspora communities are also present throughout Russia, Turkey, G ...

participated in military campaigns that were led by Poland in the 17th century. Bogdan Gurdziecki, an ethnic Georgian, became the Polish king's ambassador to the Middle East and made frequent diplomatic trips to Persia to represent Polish interests. During the war in South Ossetia in 2008, also known as the Russo-Georgian War, Poland strongly supported Georgia. Polish President Lech Kaczyéski flew to Tbilisi to rally against the Russian military intervention and the subsequent military conflict. Several European leaders met with Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili at Kaczyéski's initiative at the rally held on 12 August 2008, which was attended by over 150,000 people. The crowd responded enthusiastically to the Polish president's speech and chanted, "Poland, Poland", "Friendship, Friendship" and "Georgia, Georgia".

The main boulevard in the city of Batumi, Georgia, is named after Lech Kaczyéski and his wife, Maria.

Hungary

Hungary and Poland have enjoyed good relations since the inauguration of diplomatic relations between the two countries in the Middle Ages. Hungary and Poland have maintained a very close friendship and brotherhood "rooted in a deep history of shared monarchs, cultures, and common faith". Both countries commemorate a fraternal relationship and Friendship Day.King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16t ...

in 1576 and is the primary figure of the close ties between the countries.

Italy

Italy and Poland shared common historical backgrounds and common enemies (Austria), and a good relationship is maintained to this day. After the Revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states against the Austrian Empire, Francesco Nullo, a merchant by trade, travelled to Poland to aid the Poles in theirJanuary Uprising

The January Uprising ( pl, powstanie styczniowe; lt, 1863 meté° sukilimas; ua, ÅÀîîŧÅçÅýÅç ŢŃÅýîîůŧŧî; russian: ÅŃţîîŤŃÅç ÅýŃîîîůŧšÅç; ) was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at ...

against Russia. He was killed at the Battle of Krzykawka

Battle of Krzykawka was a military engagement that took place during the January Uprising on May 5, 1863, between Russian forces and Polish insurgents and foreign (Italian and French) volunteers allied with them. It took place close to the villag ...

in 1863 while he fought for Poland's independence. In Poland, Nullo is a national hero, and numerous streets and schools are named in his honour.

The struggle for a united and sovereign nation was a common goal for both countries and was noticed by Goffredo Mameli, a Polonophile and the author of the lyrics in the Italian national anthem, '' Il Canto degli Italiani''. Mameli featured a prominent statement in the last verse of the anthem, ''Giû l'Aquila d'Austria, le penne ha perdute. Il sangue d'Italia, il sangue Polacco....'' ("Already the Eagle of Austria has lost its plumes. The blood of Italy, the Polish blood...").

Pope John Paul II also greatly contributed to a favourable opinion of the Polish people in Italy and in the Vatican during his pontificate

The pontificate is the form of government used in Vatican City. The word came to English from French and simply means ''papacy'', or "to perform the functions of the Pope or other high official in the Church". Since there is only one bishop of Ro ...

.

United States

Tadeusz Koéciuszko and Casimir Pulaski, who fought for the independence of the United States and Poland, are seen as the foundation of Polish-American relations. However, the United States began to be involved in Poland's struggle for sovereignty during two uprisings, which took place in the 19th century. When theNovember Uprising

The November Uprising (1830ã31), also known as the PolishãRussian War 1830ã31 or the Cadet Revolution,

was an armed rebellion in the heartland of partitioned Poland against the Russian Empire. The uprising began on 29 November 1830 in W ...

started in 1830, there were very few Poles in the United States, but American views of Poland were shaped positively by their support for the American Revolution. Several young men offered their military services to fight for Poland, the most well-known of which was Edgar Allan Poe, who wrote a letter to his commanding officer on 10 March 1831 to join the Polish Army if it was created in France. Support for Poland was highest in the South, as Pulaski's death in Savannah, Georgia, was well-remembered and memorialized. The most famous landmark representing American Polonophilia of the time was Fort Pulaski

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

in the State of Georgia

Georgia is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee and North Carolina; to the northeast by South Carolina; to the southeast by the Atlantic Ocean; to the south by Florida; and to the west by ...

.

Wéodzimierz Bonawentura Krzyé¥anowski was another hero who fought at the Battle of Gettysburg and helped to repel the Louisiana Tigers. He was appointed the governor of Alabama, Georgia and served as administrator of Alaska Territory, a high distinction for a foreigner at the time. He had fled Poland after the failed 1848 Greater Poland Uprising.

Strong support for Poland and pro-Polish sentiment were also observed by US President Woodrow Wilson. In 1918, delivered his Fourteen Points as peace settlement to end World War I and stated in Point 13 that "an independent Polish state should be erected... with a free and secure access to the sea...".

US President Donald Trump also expressed his sentiment towards Poland and Polish history in his

Strong support for Poland and pro-Polish sentiment were also observed by US President Woodrow Wilson. In 1918, delivered his Fourteen Points as peace settlement to end World War I and stated in Point 13 that "an independent Polish state should be erected... with a free and secure access to the sea...".

US President Donald Trump also expressed his sentiment towards Poland and Polish history in his speech

Speech is a human vocal communication using language. Each language uses Phonetics, phonetic combinations of vowel and consonant sounds that form the sound of its words (that is, all English words sound different from all French words, even if ...

in Warsaw on 6 July 2017. Trump spoke highly of the spirit of the Polish for defending the freedom and the independence of the country several times at the speech, notably the unity of Poles against the oppression of communism. He applauded the Poles' prevailing spiritual determination and recalled the gathering of the Poles in 1979 with the famous chant "We want God". Trump also made remarks on Polish economic success and policies towards migrants.

The large Polish-American community maintains some traditional folk customs and contemporary observances, such as Dyngus Day and Pulaski Day, which became well known in American culture. It also includes the influence of Polish cuisine and the spread of famous specialties from Poland like pierogi

Pierogi are filled dumplings made by wrapping unleavened dough around a savory or sweet filling and cooking in boiling water. They are often pan-fried before serving.

Pierogi or their varieties are associated with the cuisines of Central, Easter ...

, kielbasa

Kielbasa (, ; from Polish ) is any type of meat sausage from Poland and a staple of Polish cuisine. In American English the word typically refers to a coarse, U-shaped smoked sausage of any kind of meat, which closely resembles the ''Wiejska'' ...

, Kabana sausage and bagels.

See also

* Polonophobia *Polish Americans

Polish Americans ( pl, Polonia amerykaéska) are Americans who either have total or partial Poles, Polish ancestry, or are citizens of the Republic of Poland. There are an estimated 9.15 million self-identified Polish Americans, representing abou ...

* History of Poland

* Polonization

References

{{Authority control Polish culture Polish nationalism Admiration of foreign cultures