Political Novel on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Political fiction employs narrative to

Political fiction employs narrative to

'' Nineteenth-Century Literary Criticism'', eNotes, accessed 25 August 2013 ''Coningsby'' was followed by '' Sybil; or, The Two Nations'' (1845), another political novel, which was less idealistic and more clear-eyed than ''Coningsby''; the "two nations" of its subtitle referred to the huge economic and social gap between the privileged few and the deprived working classes. The last of Disraeli's political-novel trilogy, '' Tancred; or, The New Crusade'' (1847), promoted the Church of England's role in reviving Britain's flagging spirituality. Ivan Turgenev wrote '' Fathers and Sons'' (1862) as a response to the growing cultural schism that he saw between Russia's liberals of the 1830s and 1840s, and the growing Russian nihilist movement among their sons. Both the nihilists and the 1830s liberals sought Western-based social change in Russia. Additionally, these two modes of thought were contrasted with the

Political fiction employs narrative to

Political fiction employs narrative to comment

Comment may refer to:

* Comment (linguistics) or rheme, that which is said about the topic (theme) of a sentence

* Bernard Comment (born 1960), Swiss writer and publisher

Computing

* Comment (computer programming), explanatory text or informat ...

on political events, systems and theories. Works of political fiction

Fiction is any creative work, chiefly any narrative work, portraying individuals, events, or places that are imaginary, or in ways that are imaginary. Fictional portrayals are thus inconsistent with history, fact, or plausibility. In a traditi ...

, such as political novels, often "directly criticize an existing society or present an alternative, even fantastic, reality". The political novel overlaps with the social novel

The social novel, also known as the social problem (or social protest) novel, is a "work of fiction in which a prevailing social problem, such as gender, race, or class prejudice, is dramatized through its effect on the characters of a novel". More ...

, proletarian novel

Proletarian literature refers here to the literature created by left-wing writers mainly for the class-conscious proletariat. Though the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' states that because it "is essentially an intended device of revolution", it is t ...

, and social science fiction.

Plato's ''Republic

A republic () is a "state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th c ...

'', a Socratic dialogue

Socratic dialogue ( grc, Σωκρατικὸς λόγος) is a genre of literary prose developed in Greece at the turn of the fourth century BC. The earliest ones are preserved in the works of Plato and Xenophon and all involve Socrates as the p ...

written around 380 BC, has been one of the world's most influential works of philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

and political theory

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

, both intellectually and historically. The ''Republic'' is concerned with justice ( δικαιοσύνη), the order and character of the just city-state, and the just man. Other influential politically-themed works include Thomas More's '' Utopia'' (1516), Jonathan Swift's ''Gulliver's Travels

''Gulliver's Travels'', or ''Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships'' is a 1726 prose satire by the Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan ...

'' (1726), Voltaire's ''Candide

( , ) is a French satire written by Voltaire, a philosopher of the Age of Enlightenment, first published in 1759. The novella has been widely translated, with English versions titled ''Candide: or, All for the Best'' (1759); ''Candide: or, The ...

'' (1759), and Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and became best known for her novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1852), which depicts the harsh ...

's '' Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1852).

Political fiction frequently employs satire, often in the utopian and dystopian genres.

This includes totalitarian dystopia

A dystopia (from Ancient Greek δυσ- "bad, hard" and τόπος "place"; alternatively cacotopiaCacotopia (from κακός ''kakos'' "bad") was the term used by Jeremy Bentham in his 1818 Plan of Parliamentary Reform (Works, vol. 3, p. 493). ...

s of the early 20th century such as Jack London's '' The Iron Heel'', Sinclair Lewis' '' It Can't Happen Here'', and George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitar ...

's '' Nineteen Eighty-Four''.

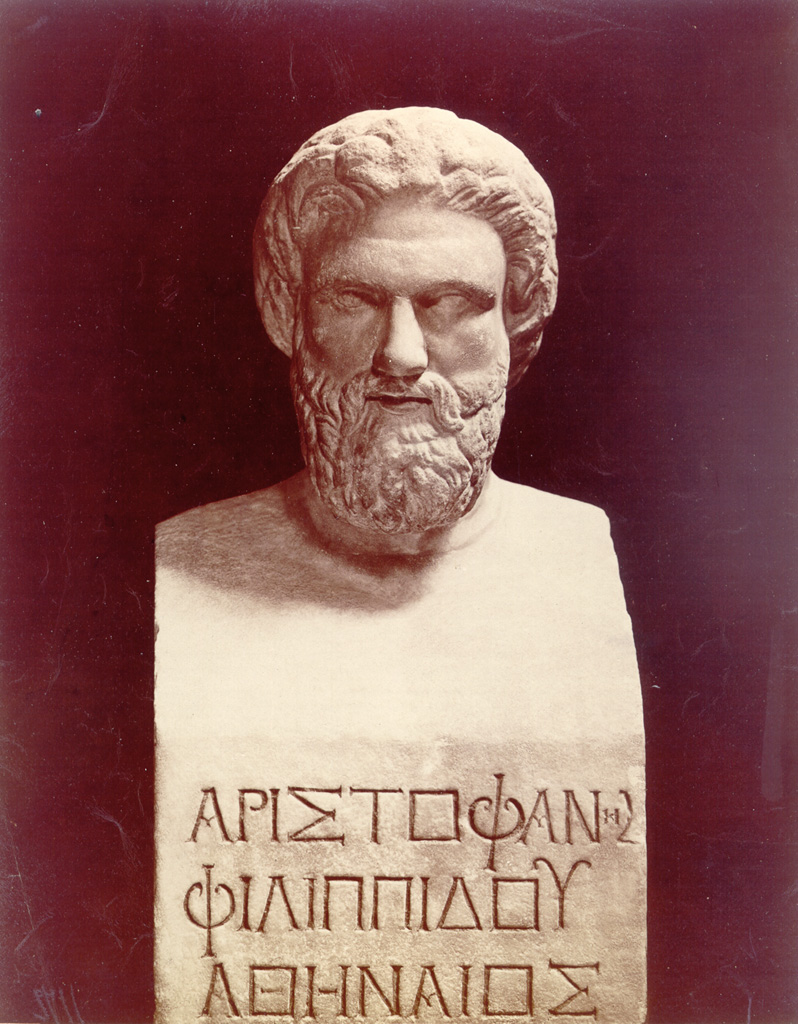

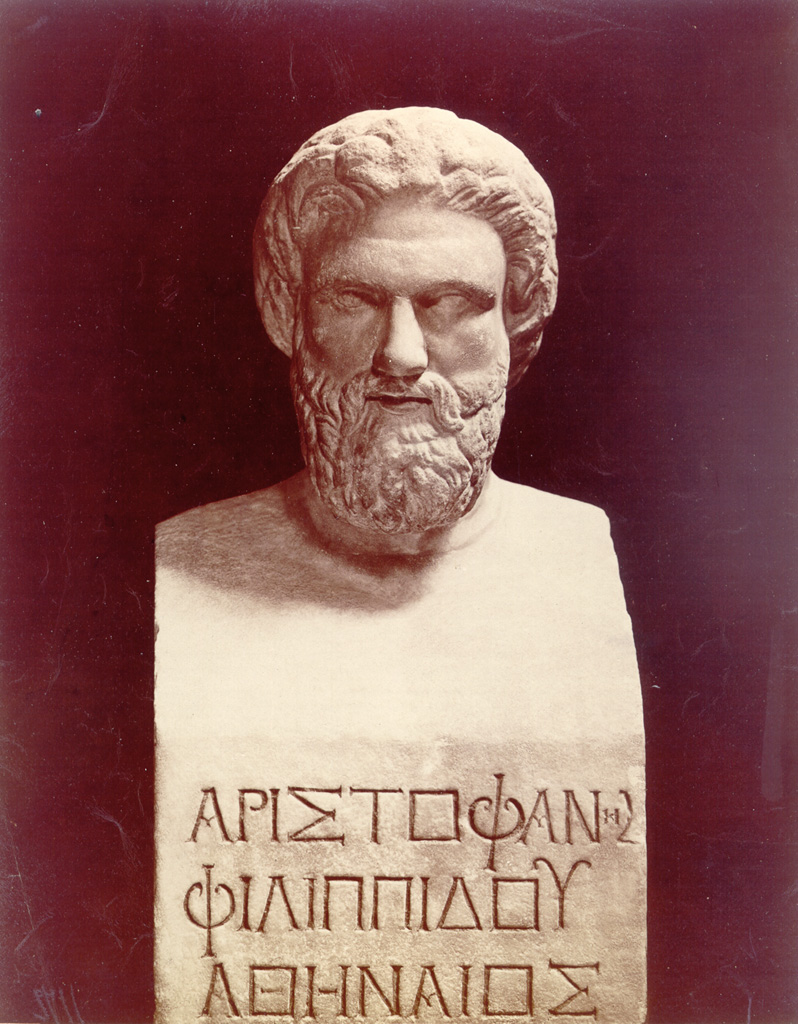

Political satire

The Greek playwright Aristophanes' plays are known for their political and social satire, particularly in his criticism of the powerful Athenian general, Cleon, in plays such as ''The Knights

''The Knights'' ( grc, Ἱππεῖς ''Hippeîs''; Attic: ) was the fourth play written by Aristophanes, who is considered the master of an ancient form of drama known as Old Comedy. The play is a satire on the social and political life of clas ...

''. Aristophanes is also notable for the persecution he underwent. Aristophanes' plays turned upon images of filth and disease. His bawdy style was adopted by Greek dramatist-comedian Menander

Menander (; grc-gre, Μένανδρος ''Menandros''; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His rec ...

, whose early play, ''Drunkenness'', contains an attack on the politician, Callimedon

Callimedon ( grc, Καλλιμέδων) was an orator and politician at Classical Athens, Athens during the 4th century BCE who was a member of the Rise of Macedon, pro-Macedonian faction in the city. None of his speeches survive, but details of ...

.

Jonathan Swift's '' A Modest Proposal'' (1729) is an 18th-century Juvenalian satirical

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or e ...

essay in which he suggests that the impoverished Irish might ease their economic troubles by selling their children as food for rich gentlemen and ladies. The satirical hyperbole mocks heartless attitudes towards the poor, as well as British policy toward the Irish in general.

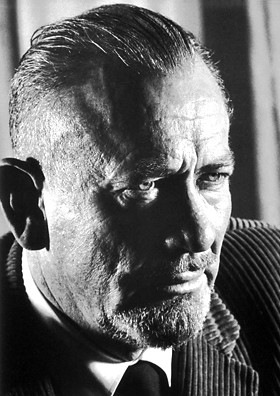

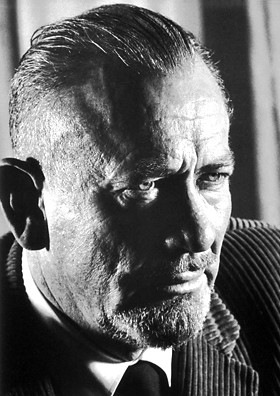

George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitar ...

's ''Animal Farm

''Animal Farm'' is a beast fable, in the form of satirical allegorical novella, by George Orwell, first published in England on 17 August 1945. It tells the story of a group of farm animals who rebel against their human farmer, hoping to crea ...

'' (1945) is an allegorical and dystopian

A dystopia (from Ancient Greek δυσ- "bad, hard" and τόπος "place"; alternatively cacotopiaCacotopia (from κακός ''kakos'' "bad") was the term used by Jeremy Bentham in his 1818 Plan of Parliamentary Reform (Works, vol. 3, p. 493). ...

novella which satirises the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Soviet Union's Stalinist era. Orwell, a democratic socialist, was a critic of Joseph Stalin and was hostile to Moscow-directed Stalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory ...

—an attitude that had been shaped by his experiences during the Spanish Civil War. The Soviet Union, he believed, had become a brutal dictatorship, built upon a cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create an id ...

and enforced by a reign of terror. Orwell described his ''Animal Farm'' as "a satirical

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or e ...

tale against Stalin", and in his essay " Why I Write" (1946) he wrote that ''Animal Farm'' was the first book in which he tried, with full consciousness of what he was doing, "to fuse political purpose and artistic purpose into one whole."

Orwell's most famous work, however, is '' Nineteen Eighty-Four'' (published in 1949), many of whose terms and concepts, such as ''Big Brother

Big Brother may refer to:

* Big Brother (''Nineteen Eighty-Four''), a character from George Orwell's novel ''Nineteen Eighty-Four''

** Authoritarian personality, any omnipresent figure representing oppressive control

** Big Brother Awards, a sat ...

'', '' doublethink'', ''thoughtcrime

Thoughtcrime is a word coined by George Orwell in his 1949 dystopian novel ''Nineteen Eighty-Four''. It describes a person's politically unorthodox thoughts, such as beliefs and doubts that contradict the tenets of Ingsoc (English Socialism) ...

'', '' Newspeak'', '' Room 101'', '' telescreen'', ''2 + 2 = 5

"Two plus two equals five" (2 + 2 = 5) is a mathematically incorrect phrase used in the 1949 dystopian novel ''Nineteen Eighty-Four'' by George Orwell. It appears as a possible statement of Ingsoc ( English Socialism) philosophy, like the ...

'', and '' memory hole'', have entered into common use. ''Nineteen Eighty-Four'' popularised the adjective " Orwellian", which describes official deception, secret surveillance, and manipulation of recorded history by a totalitarian or authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

state.The Oxford Companion to English Literature, Sixth Edition. University of Oxford Press: 2000. p. 726.

16th-century novel

The poet Jan Kochanowski's play ''The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys

''The Dismissal of the Greek Envoys'' (title also rendered as ''The Dismissal of the Grecian Envoys'', ''The Discharge of the Greek Envoys'', and ''The Envoys''; pl, Odprawa posłów greckich) is a tragedy written by Polish Renaissance poet Ja ...

'' (1578), the first tragedy written in the Polish language, recounts an incident leading up to the Trojan War. Its theme of the responsibilities of statesmanship resonates to the present day.

The book ''Utopia'' (1516), written by Sir Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord ...

, talk about a story of a different world compared to the one they live in. The character Thomas More is sent by King Henry VIII of England to negotiate the English wool trade. There he meets a man by the name Raphael Hythloday. He is a man that has been to the island on Utopia. He explains to More how their entire philosophy is to find happiness and how they all live collectively by sharing everything they have; they are a society where money does not exist. Which is very different than how England was run.

18th-century novel

The political comedy ''The Return of the Deputy'' (1790), by Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz—Polish poet, playwright, statesman, and comrade-in-arms of Tadeusz Kościuszko—was written in about two weeks' time while Niemcewicz was serving as a deputy to the historicFour-Year Sejm

The Great Sejm, also known as the Four-Year Sejm (Polish: ''Sejm Wielki'' or ''Sejm Czteroletni''; Lithuanian: ''Didysis seimas'' or ''Ketverių metų seimas'') was a Sejm (parliament) of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that was held in Wars ...

of 1788–92. The comedy's premiere in January 1791 was an enormous success, sparking widespread debate, royal communiques, and diplomatic correspondence. As Niemcewicz had hoped, it set the stage for passage of Poland's epochal Constitution of 3 May 1791, which is regarded as Europe's first, and the world's second, modern written national constitution, after the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

implemented in 1789. The comedy pits proponents against opponents of political reforms: of abolishing the destabilizing free election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative ...

of Poland's kings; of abolishing the legislatively destructive '' liberum veto''; of granting greater rights to peasants and townspeople; of curbing the privileges of the mostly self-interested noble class

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteristi ...

; and of promoting a more active Polish role in international affairs, in the interest of stopping the depredations of Poland's neighbors, Russia, Prussia, and Austria (who will in 1795 complete the dismemberment of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth). Romantic interest is provided by a rivalry between a reformer and a conservative for a young lady's hand—which is won by the proponent of reforms.

19th-century novel

An early example of the political novel is '' The Betrothed'' (1827) by Alessandro Manzoni, an Italianhistorical novel

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

. Set in northern Italy in 1628, during the oppressive years of direct Spanish rule, it has been seen sometimes as a veiled attack on the Austrian Empire, which controlled Italy at the time the novel was written. It has been called the most famous and widely read novel in the Italian language.Archibald Colquhoun. ''Manzoni and his Times.'' J. M. Dent & Sons, London, 1954.

In the 1840s British politician Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a central role in the creation o ...

wrote a trilogy of novels with political themes. With '' Coningsby; or, The New Generation'' (1844), Disraeli, in historian Robert Blake's view, "infused the novel genre with political sensibility, espousing the belief that England's future as a world power depended not on the complacent old guard, but on youthful, idealistic politicians.""Benjamin Disraeli 1804–1881"'' Nineteenth-Century Literary Criticism'', eNotes, accessed 25 August 2013 ''Coningsby'' was followed by '' Sybil; or, The Two Nations'' (1845), another political novel, which was less idealistic and more clear-eyed than ''Coningsby''; the "two nations" of its subtitle referred to the huge economic and social gap between the privileged few and the deprived working classes. The last of Disraeli's political-novel trilogy, '' Tancred; or, The New Crusade'' (1847), promoted the Church of England's role in reviving Britain's flagging spirituality. Ivan Turgenev wrote '' Fathers and Sons'' (1862) as a response to the growing cultural schism that he saw between Russia's liberals of the 1830s and 1840s, and the growing Russian nihilist movement among their sons. Both the nihilists and the 1830s liberals sought Western-based social change in Russia. Additionally, these two modes of thought were contrasted with the

Slavophile

Slavophilia (russian: Славянофильство) was an intellectual movement originating from the 19th century that wanted the Russian Empire to be developed on the basis of values and institutions derived from Russia's early history. Slavoph ...

s, who believed that Russia's path lay in its traditional spirituality. Turgenev's novel was responsible for popularizing the use of the term "nihilism

Nihilism (; ) is a philosophy, or family of views within philosophy, that rejects generally accepted or fundamental aspects of human existence, such as objective truth, knowledge, morality, values, or meaning. The term was popularized by Ivan ...

", which became widely used after the novel was published.

The Polish writer Bolesław Prus' novel, '' Pharaoh'' (1895), is set in the Egypt of 1087–85 BCE as that country experiences internal stresses and external threats that will culminate in the fall of its Twentieth Dynasty and New Kingdom

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

. The young protagonist Ramses learns that those who would challenge the powers that be

In idiomatic English, "the powers that be" (sometimes initialized as TPTB) is a phrase used to refer to those individuals or groups who collectively hold authority over a particular domain. Within this phrase, the word ''be'' is an archaic vari ...

are vulnerable to co-option, seduction, subornation, defamation

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

, intimidation, and assassination

Assassination is the murder of a prominent or important person, such as a head of state, head of government, politician, world leader, member of a royal family or CEO. The murder of a celebrity, activist, or artist, though they may not have ...

. Perhaps the chief lesson, belatedly absorbed by Ramses as pharaoh, is the importance, to power, of knowledge. Prus' vision of the fall of an ancient civilization derives some of its power from the author's intimate awareness of the final demise of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795, a century before he completed ''Pharaoh''. This is a political awareness that Prus shared with his 10-years-junior novelist compatriot, Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in t ...

, who was an admirer of Prus' writings. ''Pharaoh'' has been translated into 20 languages and adapted as a 1966 Polish feature film. It is also known to have been Joseph Stalin's favourite book.

20th-century novel

Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in t ...

wrote several novels with political themes: ''Nostromo

''Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard'' is a 1904 novel by Joseph Conrad, set in the fictitious South American republic of "Costaguana". It was originally published serially in monthly instalments of '' T.P.'s Weekly''.

In 1998, the Modern Libra ...

(1904)'', ''The Secret Agent

''The Secret Agent: A Simple Tale'' is a novel by Joseph Conrad, first published in 1907.. The story is set in London in 1886 and deals with Mr. Adolf Verloc and his work as a spy for an unnamed country (presumably Russia). ''The Secret Agent' ...

'' (1907), and

'' Under Western Eyes'' (1911). ''Nostromo'' (1904) is set amid political upheaval in the fictitious South American country of Costaguana, where a trusted Italian-descended longshoreman, Giovanni Battista Fidanza—the novel's eponymous "Nostromo" (Italian for "our man")—is instructed by English-descended silver-mine owner Charles Gould to take Gould's silver abroad so that it will not fall into the hands of revolutionaries. The role of politics is paramount in ''The Secret Agent'', as the main character, Verloc, works for a quasi-political organisation. The plot to destroy Greenwich Observatory is in itself anarchistic. Vladimir asserts that the bombing "must be purely destructive" and that the anarchists who will be implicated as the architects of the explosion "should make it clear that heyare perfectly determined to make a clean sweep of the whole social creation.". However, the political form of anarchism is ultimately controlled in the novel: the only supposed politically motivated act is orchestrated by a secret government agency. Conrad's third political novel, '' Under Western Eyes'', is connected to Russian history. Its first audience read it against the backdrop of the failed Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

and in the shadow of the movements and impulses that would take shape as the revolutions of 1917. Conrad's earlier novella, ''Heart of Darkness

''Heart of Darkness'' (1899) is a novella by Polish-English novelist Joseph Conrad in which the sailor Charles Marlow tells his listeners the story of his assignment as steamer captain for a Belgian company in the African interior. The novel ...

'' (1899), also had political implications, in its depiction of European colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 a ...

depredations in Africa, which Conrad witnessed during his employ in the Belgian Congo.

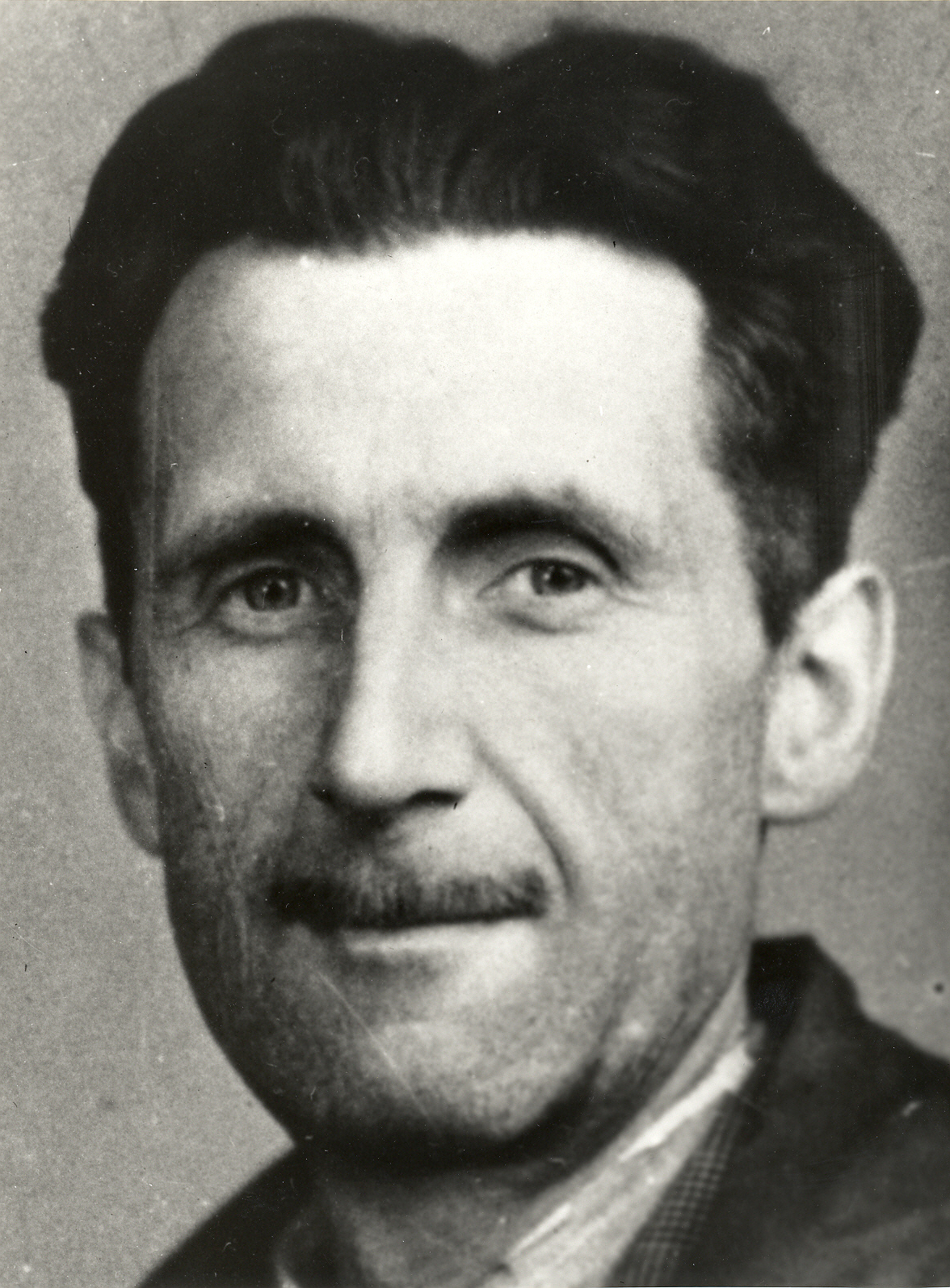

John Steinbeck

John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. (; February 27, 1902 – December 20, 1968) was an American writer and the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature winner "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humor and keen social ...

's novel '' The Grapes of Wrath'' (1939) is a depiction of the plight of the poor. However, some Steinbeck's contemporaries attacked his social and political views. Bryan Cordyack writes: "Steinbeck was attacked as a propagandist

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

and a socialist from both the left and the right of the political spectrum. The most fervent of these attacks came from the Associated Farmers of California; they were displeased with the book's depiction of California farmers' attitudes and conduct toward the migrants. They denounced the book as a 'pack of lies' and labeled it 'communist propaganda'". Some accused Steinbeck of exaggerating camp conditions to make a political point. Steinbeck had visited the camps well before publication of the novel and argued that their inhumane nature destroyed the settlers' spirit.

''The Quiet American

''The Quiet American'' is a 1955 novel by English author Graham Greene.

Narrated in the first person by journalist Thomas Fowler, the novel depicts the breakdown of French colonialism in Vietnam and early American involvement in the Vietnam W ...

'' (1955) by English novelist Graham Greene questions the foundations of growing American involvement in Vietnam in the 1950s. The novel has received much attention due to its prediction of the outcome of the Vietnam War and subsequent American foreign policy since the 1950s. Graham Greene portrays a U.S. official named Pyle as so blinded by American exceptionalism that he cannot see the calamities he brings upon the Vietnamese. The book uses Greene's experiences as a war correspondent for '' The Times'' and '' Le Figaro'' in French Indochina in 1951–54.

'' The Gay Place'' (1961) is a set of politically-themed novellas with interlocking plots and characters by American author Billy Lee Brammer. Set in an unnamed state identical to Texas, each novella has a different protagonist: Roy Sherwood, a member of the state legislature; Neil Christiansen, the state's junior senator; and Jay McGown, the governor's speech-writer. The governor himself, Arthur Fenstemaker, a master politician (said to have been based on Brammer's mentor Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

) serves as the dominant figure throughout. The book also includes characters based on Brammer, his wife Nadine,

Johnson's wife Ladybird

Coccinellidae () is a widespread family of small beetles ranging in size from . They are commonly known as ladybugs in North America and ladybirds in Great Britain. Some entomologists prefer the names ladybird beetles or lady beetles as they ...

, and his brother Sam Houston Johnson

Samuel Houston Johnson (January 31, 1914 – December 11, 1978) was an American businessman. He was the younger brother of President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Early life

Sam Houston Johnson was born in Johnson City, Texas on January 31, 1914, to Samu ...

. The book has been widely acclaimed one of the best American political novels ever written.

21st-century novel

Since 2000, there has been a surge of Transatlantic migrant literature in French, Spanish, and English, with new narratives about political topics relating to global debt, labor abuses, mass migration, and environmental crises in the Global South. Political fiction by contemporary novelists from the Caribbean, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America directly challenges political leadership, systemic racism, and economical systems. Fatou Diome, a Senegalese immigrant living France since the 1990s, writes political fiction about her experiences on France's unwelcoming borders that are dominated by white Christian culture. The work of Guadeloupean author Maryse Condé also tackles colonialism and oppression; her best known titles are ''Ségou'' (1984) and ''Ségou II'' (1985). Set in historical Segou (now part of Mali), the novels examine the violent legacies of the slave trade, Islam, Christianity, and colonization (from 1797 to 1860). A bold critic of the presidency ofNicolas Sarkozy

Nicolas Paul Stéphane Sarközy de Nagy-Bocsa (; ; born 28 January 1955) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2007 to 2012.

Born in Paris, he is of Hungarian, Greek Jewish, and French origin. Mayor of Neuilly-sur-Se ...

, French novelist Marie Ndiayes won the Prix Goncourt for "Three Strong Women

''Three Strong Women'' (french: Trois Femmes puissantes) (2009) is a novel by the French writer Marie NDiaye. It won the 2009 Prix Goncourt, France's most prestigious literary award. The English translation by John Fletcher was published in April 2 ...

"(2009) about patriarchal control.

Proletarian novel

Theproletarian novel

Proletarian literature refers here to the literature created by left-wing writers mainly for the class-conscious proletariat. Though the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' states that because it "is essentially an intended device of revolution", it is t ...

is written by workers, mainly for other workers. It overlaps and sometimes is synonymous with the working-class novel, socialist novel, social-problem novel (also problem novel, sociological novel, or social novel

The social novel, also known as the social problem (or social protest) novel, is a "work of fiction in which a prevailing social problem, such as gender, race, or class prejudice, is dramatized through its effect on the characters of a novel". More ...

), propaganda or thesis novel, and socialist-realism novel. The intention of the writers of proletarian literature is to lift the workers from the slums by inspiring them to embrace the possibilities of social change or of a political revolution. As such, it is a form of political fiction.

The proletarian novel may comment

Comment may refer to:

* Comment (linguistics) or rheme, that which is said about the topic (theme) of a sentence

* Bernard Comment (born 1960), Swiss writer and publisher

Computing

* Comment (computer programming), explanatory text or informat ...

on political events, systems, and theories, and is frequently seen as an instrument to promote social reform or political revolution among the working classes. Proletarian literature is created especially by communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

, socialist, and anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

authors. It is about the lives of the poor, and the period from 1930 to 1945, in particular, produced many such novels. However, proletarian works were also produced before and after those dates. In Britain, the terms "working-class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

" literature, novel, etc., are more generally used.

Social novel

A closely related type of novel, which frequently has a political dimension, is thesocial novel

The social novel, also known as the social problem (or social protest) novel, is a "work of fiction in which a prevailing social problem, such as gender, race, or class prejudice, is dramatized through its effect on the characters of a novel". More ...

– also known as the "social-problem" or "social-protest" novel – a "work of fiction in which a prevailing social problem, such as gender, race, or class prejudice, is dramatized through its effect on the characters of a novel". More specific examples of social problems that are addressed in such works include poverty, conditions in factories and mines, the plight of child labor, violence against women, rising criminality, and epidemics caused by overcrowding and poor sanitation in cities.

Charles Dickens was a fierce critic of the poverty and social stratification

Social stratification refers to a society's categorization of its people into groups based on socioeconomic factors like wealth, income, race, education, ethnicity, gender, occupation, social status, or derived power (social and political). As ...

of Victorian

Victorian or Victorians may refer to:

19th century

* Victorian era, British history during Queen Victoria's 19th-century reign

** Victorian architecture

** Victorian house

** Victorian decorative arts

** Victorian fashion

** Victorian literature ...

society. Karl Marx asserted that Dickens "issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists and moralists put together".. On the other hand, George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitar ...

, in his essay on Dickens, wrote: "There is no clear sign that he wants the existing order to be overthrown, or that he believes it would make very much difference if it were overthrown. For in reality his target is not so much society as 'human nature'."

Dickens's second novel, ''Oliver Twist

''Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress'', Charles Dickens's second novel, was published as a serial from 1837 to 1839, and as a three-volume book in 1838. Born in a workhouse, the orphan Oliver Twist is bound into apprenticeship with ...

'' (1839), shocked readers with its images of poverty and crime: it destroyed middle-class polemics about criminals, making any pretence to ignorance about what poverty entailed impossible.. Charles Dickens's ''Hard Times'' (1854) is set in a small Midlands

The Midlands (also referred to as Central England) are a part of England that broadly correspond to the Kingdom of Mercia of the Early Middle Ages, bordered by Wales, Northern England and Southern England. The Midlands were important in the Ind ...

industrial town and particularly criticizes the effect of Utilitarianism on the lives of cities' working classes. John Ruskin declared ''Hard Times'' his favourite Dickens work due to its exploration of important social questions. Walter Allen characterised ''Hard Times'' as an unsurpassed "critique of industrial society",

Notable examples

''This is a list of a few of the early or notable examples; others belong on the main list'' *''Panchatantra

The ''Panchatantra'' (IAST: Pañcatantra, ISO: Pañcatantra, sa, पञ्चतन्त्र, "Five Treatises") is an ancient Indian collection of interrelated animal fables in Sanskrit verse and prose, arranged within a frame story.

'' (ca. 200 BCE) by Vishnu Sarma

*'' Don Quixote'' (1605) by Miguel de Cervantes

*'' Simplicius Simplicissimus'' (1668) by Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen

*'' The Pilgrim's Progress'' (1678) by John Bunyan

*'' Persian Letters'' (1721) by Montesquieu

*''The History and Adventures of an Atom

''The History and Adventures of an Atom'' is a novel by Tobias Smollett, first published in 1769. The novel satirises English politics during the Seven Years' War.

Summary

The novel is an it-narrative, narrated by an atom in the body of a Lon ...

'' (1769) by Tobias Smollett

*''Fables and Parables

''Fables and Parables'' (''Bajki i przypowieści'', 1779), by Ignacy Krasicki (1735–1801), is a work in a long international tradition of fable-writing that reaches back to antiquity. Krasicki's fables and parables have been described as being ...

'' (1779) by Ignacy Krasicki

*''The Partisan Leader

''The Partisan Leader; A Tale of The Future'' is a political novel by the antebellum Virginia author and jurist Nathaniel Beverley Tucker. A two-volume work published in 1836 in New York City and in 1837 in Washington, D.C. under the pen-name ...

'' (1836) by Nathaniel Beverley Tucker

Nathaniel Beverley Tucker (September 6, 1784 – August 26, 1851) was an American author, judge, legal scholar, and political essayist.

Life and politics

Tucker was generally known by his middle name. He was born into a socially elite and p ...

*'' Barnaby Rudge'' (1841) by Charles Dickens

*'' A Tale of Two Cities'' (1859) by Charles Dickens

*'' The Palliser novels'' (1864–1879) by Anthony Trollope

Anthony Trollope (; 24 April 1815 – 6 December 1882) was an English novelist and civil servant of the Victorian era. Among his best-known works is a series of novels collectively known as the '' Chronicles of Barsetshire'', which revolves ar ...

*'' War and Peace'' (1869) by Leo Tolstoy

*''Demons

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in religion, occultism, literature, fiction, mythology, and folklore; as well as in media such as comics, video games, movies, anime, ...

'', also known as ''The Possessed'' or ''The Devils'' (1872), by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

*''The Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Weste ...

'' (1876) by Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

and Charles Dudley Warner

*'' Democracy: An American Novel'' (1880) by Henry Adams

Henry Brooks Adams (February 16, 1838 – March 27, 1918) was an American historian and a member of the Adams political family, descended from two U.S. Presidents.

As a young Harvard graduate, he served as secretary to his father, Charles Fra ...

*''The Princess Casamassima

''The Princess Casamassima'' is a novel by Henry James, first published as a serial in ''The Atlantic Monthly'' in 1885 and 1886 and then as a book in 1886. It is the story of an intelligent but confused young London bookbinder, Hyacinth Robinson, ...

'' (1886) by Henry James

*'' The Bostonians'' (1886) by Henry James

*'' Resurrection'' (1899) by Leo Tolstoy

*''NEQUA or The Problem of the Ages

''NEQUA or The Problem of the Ages'' is one of the first feminist science fiction books published in the United States. It was first serialized in the newspaper ''Equity''. Two editions were published in Topeka, Kansas in 1900. The title page list ...

'' (1900) Jack Adams

*'' The Old New Land'' (1902) by Theodor Herzl

*'' Mother'' (1906) by Maxim Gorky

*'' The Jungle'' (1906) by Upton Sinclair

*''The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists

''The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists'' (1914) is a semi-autobiographical novel by Irish house painter and sign writer Robert Noonan, who wrote the book in his spare time under the pen name Robert Tressell. Published after Tressell's death fro ...

'' (1914) by Robert Tressell

*'' The Trial'' (1925) by Franz Kafka

*'' The Castle'' (1926) by Franz Kafka

*''The Career of Nicodemus Dyzma

''The Career of Nicodemus Dyzma'' (Polish title: ''Kariera Nikodema Dyzmy'') is a 1932 Polish bestselling political novel by Tadeusz Dołęga-Mostowicz. It was his first major literary success, with immediate material rewards, prompting Mostowi ...

'' (1932) by Tadeusz Dołęga-Mostowicz

Tadeusz Dołęga-Mostowicz (; 10 August 1898 – 20 September 1939) was a Polish writer, journalist and author of over a dozen popular novels. One of his best known works, which in Poland became a byword for fortuitous careerism, was ''The Career ...

*''Walden Two

''Walden Two'' is a utopian novel written by behavioral psychologist B. F. Skinner, first published in 1948. In its time, it could have been considered science fiction, since science-based methods for altering people's behavior did not yet exis ...

'' (1948) by B. F. Skinner

Burrhus Frederic Skinner (March 20, 1904 – August 18, 1990) was an American psychologist, behaviorist, author, inventor, and social philosopher. He was a professor of psychology at Harvard University from 1958 until his retirement in 1974.

...

*''Dark Green, Bright Red

''Dark Green, Bright Red'' is a novel by Gore Vidal, concerning a revolution headed by a former military dictator in an unnamed Central American republic. The book was first published in 1950 in the United States by E. P. Dutton. It drew upon Vida ...

'' (1950) by Gore Vidal

*''Atlas Shrugged

''Atlas Shrugged'' is a 1957 novel by Ayn Rand. It was her longest novel, the fourth and final one published during her lifetime, and the one she considered her '' magnum opus'' in the realm of fiction writing. ''Atlas Shrugged'' includes eleme ...

'' (1957) by Ayn Rand

Alice O'Connor (born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum;, . Most sources transliterate her given name as either ''Alisa'' or ''Alissa''. , 1905 – March 6, 1982), better known by her pen name Ayn Rand (), was a Russian-born American writer and p ...

*''The Manchurian Candidate

''The Manchurian Candidate'' is a novel by Richard Condon, first published in 1959. It is a political thriller about the son of a prominent U.S. political family who is brainwashed into being an unwitting assassin for a Communist conspiracy.

The ...

'' (1959) by Richard Condon

*'' The Comedians'' (1966) by Graham Greene

*''Cancer Ward

''Cancer Ward'' (russian: links=no, italics=yes, Раковый корпус, Rakovy korpus) is a semi-autobiographical novel by Nobel Prize-winning Russian author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Completed in 1966, the novel was distributed in Russia t ...

'' (1967) by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

*'' Washington, D.C.'' (1967) by Gore Vidal

*''Burr

Burr may refer to:

Places

* Burr (crater), on the Jovian moon Callisto

*Burr, Minnesota, an unincorporated community, United States

* Burr, Missouri, an unincorporated community, United States

*Burr, Nebraska, a village, United States

* Burr, Sa ...

'' (1973) by Gore Vidal

*''The Chocolate War

''The Chocolate War'' is a 1974 young adult literature, young adult novel by American author Robert Cormier. It was adapted into a film in 1988. Although it received mixed reviews at the time of its publication, some reviewers have argued it is o ...

'' (1974) by Robert Cormier

*'' Guerrillas'' (1975) by V. S. Naipaul

*'' Ragtime'' (1975) by E.L. Doctorow

*''1876

Events

January–March

* January 1

** The Reichsbank opens in Berlin.

** The Bass Brewery Red Triangle becomes the world's first registered trademark symbol.

* February 2 – The National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs i ...

'' (1976) by Gore Vidal

*'' Vineland'' (1990) by Thomas Pynchon

*''From the Fatherland with Love

is a novel by Ryū Murakami, first published in Japanese in 2005 and translated into English in 2013 by Ralph McCarthy, Charles De Wolf, and Ginny Tapley. The novel depicts an alternate history in which North Korea invades and then occupies the ...

'' (2005) by Ryu Murakami

*''Occupied'' (2015); ''The Little Voice'' (2016); ''Money Power Love'' (2017) by Joss Sheldon Joss Sheldon (born 7 April 1982, Barnet, UK) is an author who has released five novels; ''Individutopia'' (2018), ''Money Power Love'' (2017), ''The Little Voice'' (2016), ''Occupied'' (2015) and ''Involution & Evolution'' (2014). He released his fi ...

Science fiction

* ''Starship Troopers

''Starship Troopers'' is a military science fiction novel by American writer Robert A. Heinlein. Written in a few weeks in reaction to the US suspending nuclear tests, the story was first published as a two-part serial in ''The Magazine of F ...

'' (1959) by Robert A. Heinlein

*'' Brave New World'' (1932) by Aldous Huxley

* '' The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia'' (1974) by Ursula K. Le Guin

Ursula Kroeber Le Guin (; October 21, 1929 – January 22, 2018) was an American author best known for her works of speculative fiction, including science fiction works set in her Hainish universe, and the '' Earthsea'' fantasy series. She was ...

* The '' Mars trilogy'' (1990s) by Kim Stanley Robinson

See also

* Augustan literature * Political cartoon * Political satire * Politics in fiction * Political poetry *Proletarian literature

Proletarian literature refers here to the literature created by left-wing writers mainly for the class-conscious proletariat. Though the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' states that because it "is essentially an intended device of revolution", it is ...

Notes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Political Fiction Literary genres Political art Fiction