Polish minority in Soviet Union on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Polish minority in the Soviet Union are

Millions of Poles lived within the

Millions of Poles lived within the

During

During

History of Poles in Kazakhstan

Soviet repressions against Poles and citizens of Poland

{{Polish diaspora Ethnic Poles in the Soviet Union Second Polish Republic Poland in World War II Polish People's Republic Poland–Soviet Union relations

Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of origin. Historically, the word was used first in reference to the dispersion of Greeks in the Hellenic world, and later Jews after ...

who used to reside near or within the borders of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

before its dissolution

Dissolution may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Books

* ''Dissolution'' (''Forgotten Realms'' novel), a 2002 fantasy novel by Richard Lee Byers

* ''Dissolution'' (Sansom novel), a 2003 historical novel by C. J. Sansom Music

* Dissolution, in mu ...

. Some of them continued to live in the post-Soviet states

The post-Soviet states, also known as the former Soviet Union (FSU), the former Soviet Republics and in Russia as the near abroad (russian: links=no, –±–ª–∏–∂–Ω–µ–µ –∑–∞—Ä—É–±–µ–∂—å–µ, blizhneye zarubezhye), are the 15 sovereign states that wer ...

, most notably in Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

, Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, –Ý–µ—Å–ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫–∞ –ë–µ–ª–∞—Ä—É—Å—å, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

, and Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

, the areas historically associated with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

, as well as in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

and Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Az…ôrbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

among others.

History of Poles in the Soviet Union

1917–1920

Millions of Poles lived within the

Millions of Poles lived within the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

(along with Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

and the Prussian Kingdom

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918. Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. R ...

) following the military Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland were three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth that took place toward the end of the 18th century and ended the existence of the state, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland and Lithuania for 12 ...

throughout the 19th century, which resulted in the extinction of the Polish state. After the Russian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

, followed by the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

, the majority of the Polish population saw cooperation with the Bolshevik forces as betrayal and treachery to Polish national interests.J. M. Kupczak "Stosunek władz bolszewickich do polskiej ludności na Ukrainie (1921–1939), Wrocławskie Studia Wschodnie 1 (1997) Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego, 1997 page 47–62" IPN Bulletin 11(34) 2003. Polish writer and philosopher Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (; 24 February 188518 September 1939), commonly known as Witkacy, was a Polish writer, painter, philosopher, theorist, playwright, novelist, and photographer active before World War I and during the interwar period.

...

lived through the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

while in St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, –°–∞–Ω–∫—Ç-–ü–µ—Ç–µ—Ä–±—É—Ä–≥, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=Ààsankt p ≤…™t ≤…™rÀàburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914‚Äì1924) and later Leningrad (1924‚Äì1991), i ...

. What he saw, had a profound effect on his works, many of which display themes of the horrors of the Civil War he witnessed.

Among the many Polish victims of the revolution was the father of Polish eminent composer Witold Lutosławski

Witold Roman Lutosławski (; 25 January 1913 – 7 February 1994) was a Polish composer and conductor. Among the major composers of 20th-century classical music, he is "generally regarded as the most significant Polish composer since Szyman ...

, Marian Lutosławski

Marian Lutosławski (1871 – 5 September 1918) was a Polish mechanical engineer and inventor born during the foreign partitions of Poland. He studied at the Technical University in Riga, then also part of Russia, and obtained a diploma in electric ...

and his brother Józef, murdered in Moscow in 1918 as alleged "counter-revolutionaries".

There were also some Poles (or those of partial Polish descent) associated with the communist movement. Famous revolutionaries include Konstantin Rokossovsky

Konstantin Konstantinovich (Xaverevich) Rokossovsky (Russian: –ö–æ–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–Ω—Ç–∏–Ω –ö–æ–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–Ω—Ç–∏–Ω–æ–≤–∏—á –Ý–æ–∫–æ—Å—Å–æ–≤—Å–∫–∏–π; pl, Konstanty Rokossowski; 21 December 1896 ‚Äì 3 August 1968) was a Soviet and Polish officer who becam ...

, Vyacheslav Menzhinsky

Vyacheslav Rudolfovich Menzhinsky (russian: –í—è—á–µ—Å–ª–∞ÃÅ–≤ –Ý—É–¥–æÃÅ–ª—å—Ñ–æ–≤–∏—á –ú–µ–Ω–∂–∏ÃÅ–Ω—Å–∫–∏–π, pl, Wies≈Çaw Mƒô≈ºy≈Ñski; 19 August 1874 ‚Äì 10 May 1934) was a Polish-Russian Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet statesman and Communist ...

, Julian Marchlewski

Julian Baltazar Józef Marchlewski (17 May 1866 – 22 March 1925) was a Polish communist politician, revolutionary activist and publicist who served as chairman of the Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee. He was also known under the alia ...

, Stanislaw Kosior, Karol ≈öwierczewski

Karol Wacław Świerczewski (; callsign ''Walter''; 10 February 1897 Р28 March 1947) was a Polish and Soviet Red Army general and statesman. He was a Bolshevik Party member during the Russian Civil War and a Soviet officer in the wars fough ...

and Felix Dzerzhinsky

Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky ( pl, Feliks Dzierżyński ; russian: Фе́ликс Эдму́ндович Дзержи́нский; – 20 July 1926), nicknamed "Iron Felix", was a Bolshevik revolutionary and official, born into Poland, Polish n ...

, founder of the Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, –í—Å–µ—Ä–æ—Å—Å–∏–π—Å–∫–∞—è —á—Ä–µ–∑–≤—ã—á–∞–π–Ω–∞—è –∫–æ–º–∏—Å—Å–∏—è, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fs ≤…™r…êÀàs ≤ijsk…ôj…ô t…ïr ≤…™zv…®Ààt…ï√¶jn…ôj…ô k…êÀàm ≤is ≤…™j…ô), abbreviated ...

secret police which would later turn into the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

. The Soviet Union also organized Polish units in the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: –Ý–∞–±–æÃÅ—á–µ-–∫—Ä–µ—Å—Ç—å—èÃÅ–Ω—Å–∫–∞—è –ö—Ä–∞ÃÅ—Å–Ω–∞—è –∞—Ä–º–∏—è),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

and a Polish Communist government-in-exile, however the former were persecuted and subject to mock trial

A mock trial is an act or imitation trial. It is similar to a moot court, but mock trials simulate lower-court trials, while moot court simulates appellate court hearings. Attorneys preparing for a real trial might use a mock trial consisting ...

s following the end of the Second World War and the latter being appointed and installed by the Soviet regime as opposed to the legitimate government-in-exile based in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

. Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee

Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee ( pl, Tymczasowy Komitet Rewolucyjny Polski, Polrewkom; russian: Польревком) (July–August 1920) was a revolutionary committee created under the patronage of Soviet Russia with the goal to e ...

was created in 1920 but failed to control Poland.

1921–1938

Polish communities were inherited fromImperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

after the creation of the Soviet Union. After World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

reestablished itself as an independent country, and its borders with the USSR were finalized by the Peace of Riga

The Peace of Riga, also known as the Treaty of Riga ( pl, Traktat Ryski), was signed in Riga on 18 March 1921, among Poland, Soviet Russia (acting also on behalf of Soviet Belarus) and Soviet Ukraine. The treaty ended the Polish–Soviet War.

...

in 1921 at the end of the Polish-Soviet War, which left significant territories populated by Poles near or within the confines of the Soviet Union. According to the 1926 Soviet census, there were a total of 782,334 Poles in the USSR. The largest concentration of Poles was in what is now modern-day West Ukraine

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine ( uk, Західна Україна, Zakhidna Ukraina or , ) is the territory of Ukraine linked to the former Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, which was part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Austrian ...

, where according to the Soviet census in 1926 476,435 Poles lived. Those estimates are considered to have been lowered by Soviet officials. Church and independent estimates show estimates of 650,000 to 700,000 Poles living in that area. This suggests that the total Polish population of the USSR was in excess of 1,000,000.

Initially the Soviets pursued a policy where the local national language was used as a tool for eradication of national identity in favour of "communist education of masses". In the case of the Poles this meant a goal of Sovietisation

Sovietization (russian: –°–æ–≤–µ—Ç–∏–∑–∞—Ü–∏—è) is the adoption of a political system based on the model of soviets (workers' councils) or the adoption of a way of life, mentality, and culture modelled after the Soviet Union. This often included ...

of the Polish population. However this proved extremely difficult as the Soviet communists themselves realised that the Poles were en masse opposed to communist ideology, seeing it as hostile to Polish identity and their predominant Roman Catholic religion. The policy of religious discrimination, plunder and terror further strengthened Polish resistance to Soviet rule. As a result, the Soviet authorities started to imprison and forcefully remove all those seen as an obstacle to their policies.

Two Polish Autonomous District

Polish National Districts (called in Russian "–ø–æ–ª—Ä–∞–π–æ–Ω—ã", ''polrajony'', an abbreviation for "–ø–æ–ª—å—Å–∫–∏–µ –Ω–∞—Ü–∏–æ–Ω–∞–ª—å–Ω—ã–µ —Ä–∞–π–æ–Ω—ã", "Polish national raions") were in the interbellum period possessing some form of a na ...

s were created, with one in Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, –Ý–µ—Å–ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫–∞ –ë–µ–ª–∞—Ä—É—Å—å, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

and one in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

. The first one was named ''Dzierzynszczyzna

Polish National Districts (called in Russian "–ø–æ–ª—Ä–∞–π–æ–Ω—ã", ''polrajony'', an abbreviation for "–ø–æ–ª—å—Å–∫–∏–µ –Ω–∞—Ü–∏–æ–Ω–∞–ª—å–Ω—ã–µ —Ä–∞–π–æ–Ω—ã", "Polish national raions") were in the interbellum period possessing some form of a na ...

'', after Felix Dzierżyński; the second was named ''Marchlewszczyzna

Polish National Districts (called in Russian "–ø–æ–ª—Ä–∞–π–æ–Ω—ã", ''polrajony'', an abbreviation for "–ø–æ–ª—å—Å–∫–∏–µ –Ω–∞—Ü–∏–æ–Ω–∞–ª—å–Ω—ã–µ —Ä–∞–π–æ–Ω—ã", "Polish national raions") were in the interbellum period possessing some form of a na ...

'' after Julian Marchlewski

Julian Baltazar Józef Marchlewski (17 May 1866 – 22 March 1925) was a Polish communist politician, revolutionary activist and publicist who served as chairman of the Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee. He was also known under the alia ...

. Following the failure of the Sovietisation of the USSR's Polish minority, the Soviet rulers decided to portray Poles as enemies of the state and use them to fuel Ukrainian nationalism

Ukrainian nationalism refers to the promotion of the unity of Ukrainians as a people and it also refers to the promotion of the identity of Ukraine as a nation state. The nation building that arose as nationalism grew following the French Revol ...

in order to direct Ukrainian anger away from the Soviet government. After 1928 Soviet policies turned to outright eradication of Polish national identity. Special centers were established where the youth was indoctrinated towards hatred against the Polish state, all contacts with relatives within Poland were dangerous and could result in imprisonment. Newspapers printed out in the Polish language were de facto used to print anti-Polish

Polonophobia, also referred to as anti-Polonism, ( pl, Antypolonizm), and anti-Polish sentiment are terms for negative attitudes, prejudices, and actions against Poles as an ethnic group, Poland as their country, and their culture. These incl ...

propaganda. Following attacks on the Polish minority, from 18 February 1930 till 19 March 1930 over 100,000 people from Polish areas were expelled by the Soviet authorities.

Following the collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member ...

of agriculture under Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

, both autonomies were abolished and their populations were subsequently deported to Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

in 1934–1938. Many people starved during the deportation and after, since the deported were moved to sparsely populated areas, unprepared for migration, lacking basic facilities and infrastructure. The survivors were under the supervision of the OGPU

The Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU; russian: –û–±—ä–µ–¥–∏–Ω—ë–Ω–Ω–æ–µ –≥–æ—Å—É–¥–∞—Ä—Å—Ç–≤–µ–Ω–Ω–æ–µ –ø–æ–ª–∏—Ç–∏—á–µ—Å–∫–æ–µ —É–ø—Ä–∞–≤–ª–µ–Ω–∏–µ) was the intelligence and state security service and secret police of the Soviet Union f ...

/NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

, cruelly punished for any sign of discontent. 21,000 Poles died during the Holodomor

The Holodomor ( uk, Голодомо́р, Holodomor, ; derived from uk, морити голодом, lit=to kill by starvation, translit=moryty holodom, label=none), also known as the Terror-Famine or the Great Famine, was a man-made famin ...

.

In 1936 the Poles were deported from the territories of Belarus and Ukraine adjacent to the state border (the first recorded deportation of a whole ethnic group in the USSR). Tens of thousands of ethnic Poles became victims of the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: –ë–æ–ª—å—à–æ–π —Ç–µ—Ä—Ä–æ—Ä), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-–π –≥–æ–¥, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

in 1937–1938 (see Polish operation of the NKVD

The ''Polish Operation'' of the NKVD (Soviet security service) in 1937–1938 was an anti-Polish mass-ethnic cleansing operation of the NKVD carried out in the Soviet Union against Poles (labeled by the Soviets as "agents") during the period of ...

). The Communist Party of Poland

The interwar Communist Party of Poland ( pl, Komunistyczna Partia Polski, KPP) was a communist party active in Poland during the Second Polish Republic. It resulted from a December 1918 merger of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland a ...

was also decimated in the Great Purge and was disbanded in 1938. Another decimated group of Poles was the Roman Catholic clergy, who opposed the forced atheization.

A number of Poles fled to Poland during this time, among them Igor Newerly

Igor Newerly or Igor Abramow-Newerly (24 March 1903, Białowieża – 19 October 1987, Warsaw, Poland) was a Polish novelist and educator. He was born into a Czech-Russian family. His son is Polish novelist Jarosław Abramow-Newerly. His gran ...

and Tadeusz Borowski

Tadeusz Borowski (; 12 November 1922 – 3 July 1951) was a Polish writer and journalist. His wartime poetry and stories dealing with his experiences as a prisoner at Auschwitz are recognized as classics of Polish literature.

Early life

Borow ...

.

1939–1947

During

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, after the Soviet invasion of Poland

The Soviet invasion of Poland was a military operation by the Soviet Union without a formal declaration of war. On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east, 16 days after Nazi Germany invaded Poland from the west. Subse ...

the Soviet Union occupied vast areas of eastern Poland (referred to in Poland as ''Kresy wschodnie

Eastern Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Wschodnie) or simply Borderlands ( pl, Kresy, ) was a term coined for the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic during the interwar period (1918–1939). Largely agricultural and extensively multi-ethnic, i ...

'' or "eastern Borderlands"), and another 5.2–6.5 million ethnic Poles (from the total population of about 13.5 million residents of these territories) were added, followed by further large-scale forcible deportations to Siberia, Kazakhstan and other remote areas of the Soviet Union.

The number of Poland's citizens held captive in the Soviet Union is a matter of dispute, and ranges from over 300,000 up to nearly 2 million, according to various sources. On March 30, 2004, the head of the Archival Service of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

n Foreign Intelligence Service, General Vasili Khristoforov gave alleged exact numbers of deported Poles. According to him, in 1940 exactly 297,280 Poles were deported, in June 1941 another 40,000. These numbers do not include P.O.W.s, prisoners, small groups, people arrested trying to cross the new borders, people who voluntarily moved into the USSR, and men drafted into the Red Army and into construction battalions or ''stroybats''.

In August 1941, following the German attack on the USSR and the dramatic change in Soviet/Polish relations, according to a January 15, 1943, note from Beria to Stalin, 389,041 Polish citizens (including 200,828 ethnic Poles, 90,662 Jews, 31,392 Ukrainians, 27,418 Belorussians, 3,421 Russians, and 2,291 persons of other nationalities) held in special settlements and prisoner of war camps were granted 'amnesty' and allowed to enroll in Polish army units. The location of reception centres was kept secret and no travel facilities provided. Nevertheless, 119,855 Poles were evacuated to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

(Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

) with General Anders' army

Anders' Army was the informal yet common name of the Polish Armed Forces in the East in the 1941–42 period, in recognition of its commander Władysław Anders. The army was created in the Soviet Union but, in March 1942, based on an understandi ...

, which subsequently fought alongside the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

in Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and Italy; 36,150 were transferred to the Polish Army which fought with the Red Army on the Eastern Front and 11,516 are reported to have died in 1941–1943.Stephen Wheatcroft

Stephen George Wheatcroft (born 1 June 1947) is a Professorial Fellow of the School of Historical Studies, University of Melbourne. His research interests include Russian pre-revolutionary and Soviet social, economic and demographic history, as ...

, "The Scale and Nature of German and Soviet Repression and Mass Killings, 1930–1945", ''Europe-Asia Studies

''Europe-Asia Studies'' is an academic peer-reviewed journal published 10 times a year by Routledge on behalf of the Institute of Central and East European Studies, University of Glasgow, and continuing (since vol. 45, 1993) the journal ''Soviet St ...

'', Vol.48, No.8, 1996, p. 1345

The following are cases of direct executions of Poles during the 1939–1941 occupation:

*Katyn massacre

The Katyn massacre, "Katyń crime"; russian: link=yes, Катынская резня ''Katynskaya reznya'', "Katyn massacre", or russian: link=no, Катынский расстрел, ''Katynsky rasstrel'', "Katyn execution" was a series of m ...

about 22,000

* executions of prisoners after the German invasion 1941.

After World War II most Poles from ''Kresy

Eastern Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Wschodnie) or simply Borderlands ( pl, Kresy, ) was a term coined for the eastern part of the Second Polish Republic during the interwar period (1918–1939). Largely agricultural and extensively multi-ethnic, it ...

'' were expelled into Poland, but officially 1.3 million stayed in the USSR. Some of them were motivated by the traditional Polish belief that one day they would become again lawful owners of the land they lived on. Some of them were kept forcefully in. Some simply stayed, without force or ideological reasons.

Wanda Wasilewska

ukr, –í–∞–Ω–¥–∞ –õ—å–≤—ñ–≤–Ω–∞ –í–∞—Å–∏–ª–µ–≤—Å—å–∫–∞ rus, –í–∞–Ω–¥–∞ –õ—å–≤–æ–≤–Ω–∞ –í–∞—Å–∏–ª–µ–≤—Å–∫–∞—è

, native_name_lang =

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Kraków, Austria-Hungary

, death_date =

, death_place ...

was an exceptional case – she became a Soviet citizen and did not return after the war.

1947–1991

The Polish minority was one of the few whose numbers decreased over time, according to official statistics. There was also therepatriation of Poles (1955–1959)

Repatriation of Polish population in the years of 1955–1959 (also known as the ''second repatriation'', to distinguish it from the ''first repatriation'' in the years 1944-1946) was the second wave of forced repatriation (in fact, deportation) o ...

.

After 1989, Poles who survived in Kazakhstan started to emigrate due to national tensions, mainly to Russia and, supported by an immigration society, to Poland. The number remaining is between 50,000 and 100,000.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, –Ý–∞–∑–≤–∞ÃÅ–ª –°–æ–≤–µÃÅ—Ç—Å–∫–æ–≥–æ –°–æ—éÃÅ–∑–∞, r=Razv√°l Sov√©tskogo Soy√∫za, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

in 1991, the following post-Soviet countries have significant Polish minorities:

*Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

, around 250,000 (7% of population), see also Polish minority in Lithuania

The Poles in Lithuania ( pl, Polacy na Litwie, lt, Lietuvos lenkai), estimated at 183,000 people in the Lithuanian census of 2021 or 6.5% of Lithuania's total population, are the country's largest ethnic minority.

During the Polish–Lithuan ...

,

*Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, –Ý–µ—Å–ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫–∞ –ë–µ–ª–∞—Ä—É—Å—å, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

, at least 420,000 (almost 4.5% of population), see also Polish minority in Belarus

The Polish minority in Belarus numbers officially 288,000 according to 2019 census.. Listing total population of Belarus with population by age and sex, marital status, education, nationality, language and livelihood ("–û–±—â–∞—è —á–∏—Å–ª–µ–Ω–Ω ...

,

*Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

, at least 150,000, see also Polish minority in Ukraine

The Polish minority in Ukraine officially numbers about 144,130 (according to the 2001 census),

,

*Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, more than 100,000, see also Polish minority in Russia

There are currently more than 47,000 ethnic Poles living in the Russian Federation. This includes autochthonous Poles as well as those forcibly deported during and after World War II; the total number of Poles in what was the former Soviet Union i ...

,

*Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

– between 60,000 and 100,000, see also Poles in Kazakhstan

Poles in Kazakhstan form one portion of the Polish diaspora in the former Soviet Union. Slightly less than half of Kazakhstan's Poles live in the Karaganda region, with another 2,500 in Astana, 1,200 in Almaty, and the rest scattered throughout r ...

.

*Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

, around 50,000, see also Poles in Latvia

The Polish minority in Latvia numbers about 51,548 and (according to the Latvian data from 2011) forms 2.3% of the population of Latvia. Poles are concentrated in the former Inflanty Voivodeship

The Inflanty Voivodeship ( pl, Województwo infla ...

.

*Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Az…ôrbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

– between 1,000 and 2,000, see also Poles in Azerbaijan.

*Polish minorities are also found in Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, Moldova

Moldova ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Moldova ( ro, Republica Moldova), is a Landlocked country, landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The List of states ...

and Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: –£–∑–±–µ–∫–∏—Å—Ç–∞–Ω), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: –Ý–µ—Å–ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫–∞ –£–∑–±–µ–∫–∏—Å—Ç–∞–Ω), is a doubly landlocked cou ...

.

Demographics

The Polish population in the Soviet Union peaked in 1959, decreased by about 20% by 1970, and then decreased extremely slowly between 1970 and 1989.List of prominent Soviets of Polish descent

*Vikenty Veresaev

Vikenty Vikentyevich Smidovich (16 January 1867 Р3 June 1945), better known by his pen name Vikenty Vikentyevich Veresaev, (russian: Вике́нтий Вике́нтьевич Вереса́ев) was a Russian and Soviet writer, translat ...

(birth name Smidovich) - writer

* Vatsalv Vorovsky (Wacław Worowski) - revolutionary, one of the first Soviet diplomats and head of the state publishing house

*Gleb Krzhizhanovsky

Gleb Maximilianovich Krzhizhanovsky (russian: Глеб Максимилианович Кржижановский; 24 January 1872 – 31 March 1959) was a Soviet scientist, statesman, revolutionary, Old Bolshevik, and state figure as well as a ge ...

- Chief of the Russian Electrification Commission, responsible for fulfillment of the GOELRO

GOELRO (russian: link=no, –ì–û–≠–õ–Ý–û) was the first Soviet plan for national economic recovery and development. It became the prototype for subsequent Five-Year Plans drafted by Gosplan. GOELRO is the transliteration of the Russian abbreviation ...

program

* Felix Dzerzhinsky

Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky ( pl, Feliks Dzierżyński ; russian: Фе́ликс Эдму́ндович Дзержи́нский; – 20 July 1926), nicknamed "Iron Felix", was a Bolshevik revolutionary and official, born into Poland, Polish n ...

(Feliks Dzierżyński) - creator and the first chairman of the Soviet security service, Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, –í—Å–µ—Ä–æ—Å—Å–∏–π—Å–∫–∞—è —á—Ä–µ–∑–≤—ã—á–∞–π–Ω–∞—è –∫–æ–º–∏—Å—Å–∏—è, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fs ≤…™r…êÀàs ≤ijsk…ôj…ô t…ïr ≤…™zv…®Ààt…ï√¶jn…ôj…ô k…êÀàm ≤is ≤…™j…ô), abbreviated ...

, later GPU

A graphics processing unit (GPU) is a specialized electronic circuit designed to manipulate and alter memory to accelerate the creation of images in a frame buffer intended for output to a display device. GPUs are used in embedded systems, mobil ...

, OGPU

The Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU; russian: –û–±—ä–µ–¥–∏–Ω—ë–Ω–Ω–æ–µ –≥–æ—Å—É–¥–∞—Ä—Å—Ç–≤–µ–Ω–Ω–æ–µ –ø–æ–ª–∏—Ç–∏—á–µ—Å–∫–æ–µ —É–ø—Ä–∞–≤–ª–µ–Ω–∏–µ) was the intelligence and state security service and secret police of the Soviet Union f ...

(1917-1926)

* Vyacheslav Menzhinsky

Vyacheslav Rudolfovich Menzhinsky (russian: –í—è—á–µ—Å–ª–∞ÃÅ–≤ –Ý—É–¥–æÃÅ–ª—å—Ñ–æ–≤–∏—á –ú–µ–Ω–∂–∏ÃÅ–Ω—Å–∫–∏–π, pl, Wies≈Çaw Mƒô≈ºy≈Ñski; 19 August 1874 ‚Äì 10 May 1934) was a Polish-Russian Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet statesman and Communist ...

(Wiaczesław Mienżyński or Mężyński) - chairman of the OGPU

The Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU; russian: –û–±—ä–µ–¥–∏–Ω—ë–Ω–Ω–æ–µ –≥–æ—Å—É–¥–∞—Ä—Å—Ç–≤–µ–Ω–Ω–æ–µ –ø–æ–ª–∏—Ç–∏—á–µ—Å–∫–æ–µ —É–ø—Ä–∞–≤–ª–µ–Ω–∏–µ) was the intelligence and state security service and secret police of the Soviet Union f ...

(1926-1934)

* Mechislav Kozlovsky - communist diplomat and lawyer

*Andrey Vyshinsky

Andrey Yanuaryevich Vyshinsky (russian: Андре́й Януа́рьевич Выши́нский; pl, Andrzej Wyszyński) ( Р22 November 1954) was a Soviet politician, jurist and diplomat.

He is known as a state prosecutor of Joseph ...

(''Andrzej Wyszyński)'' - Soviet jurist and Prosecutor General of the Soviet Union

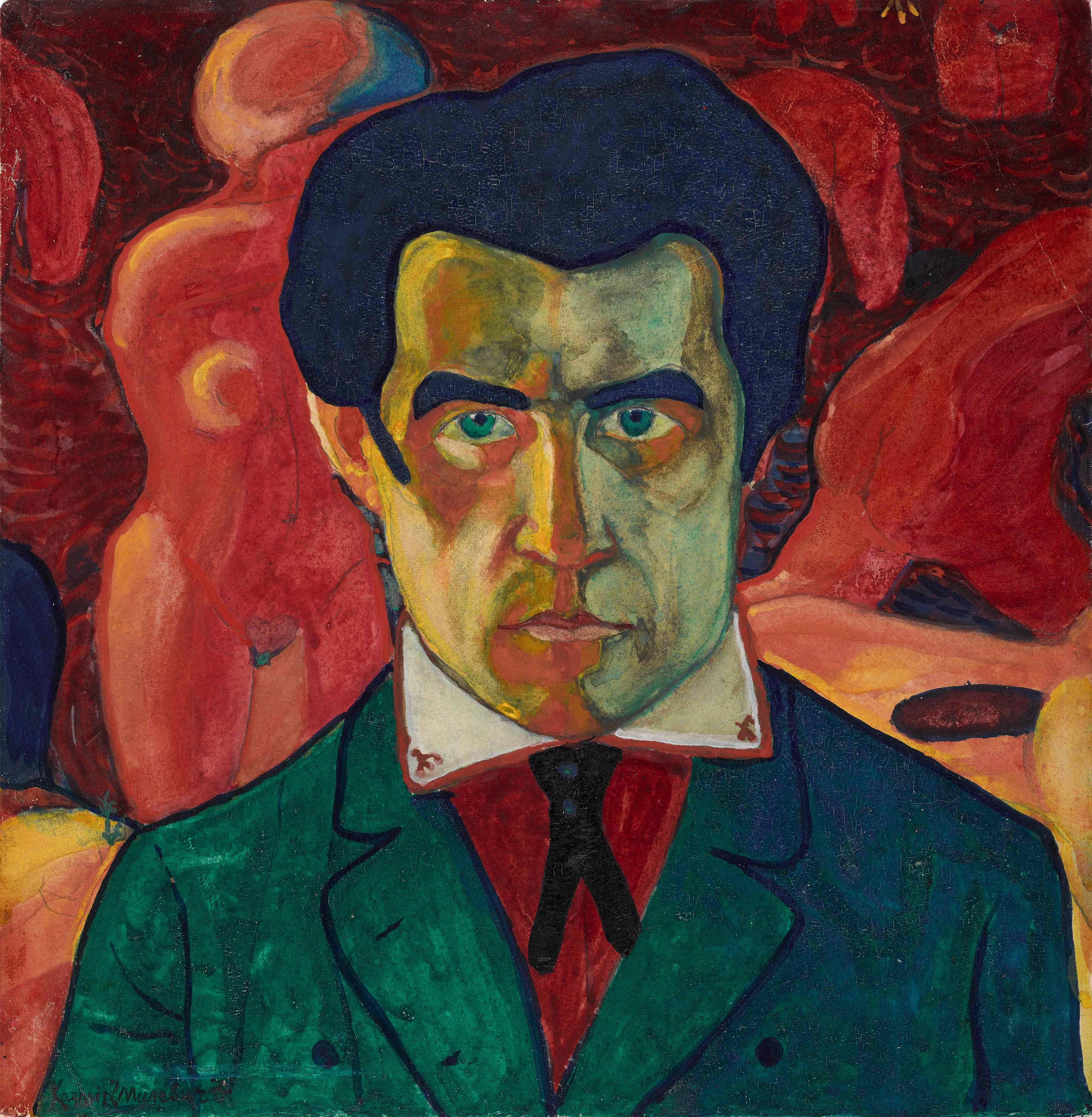

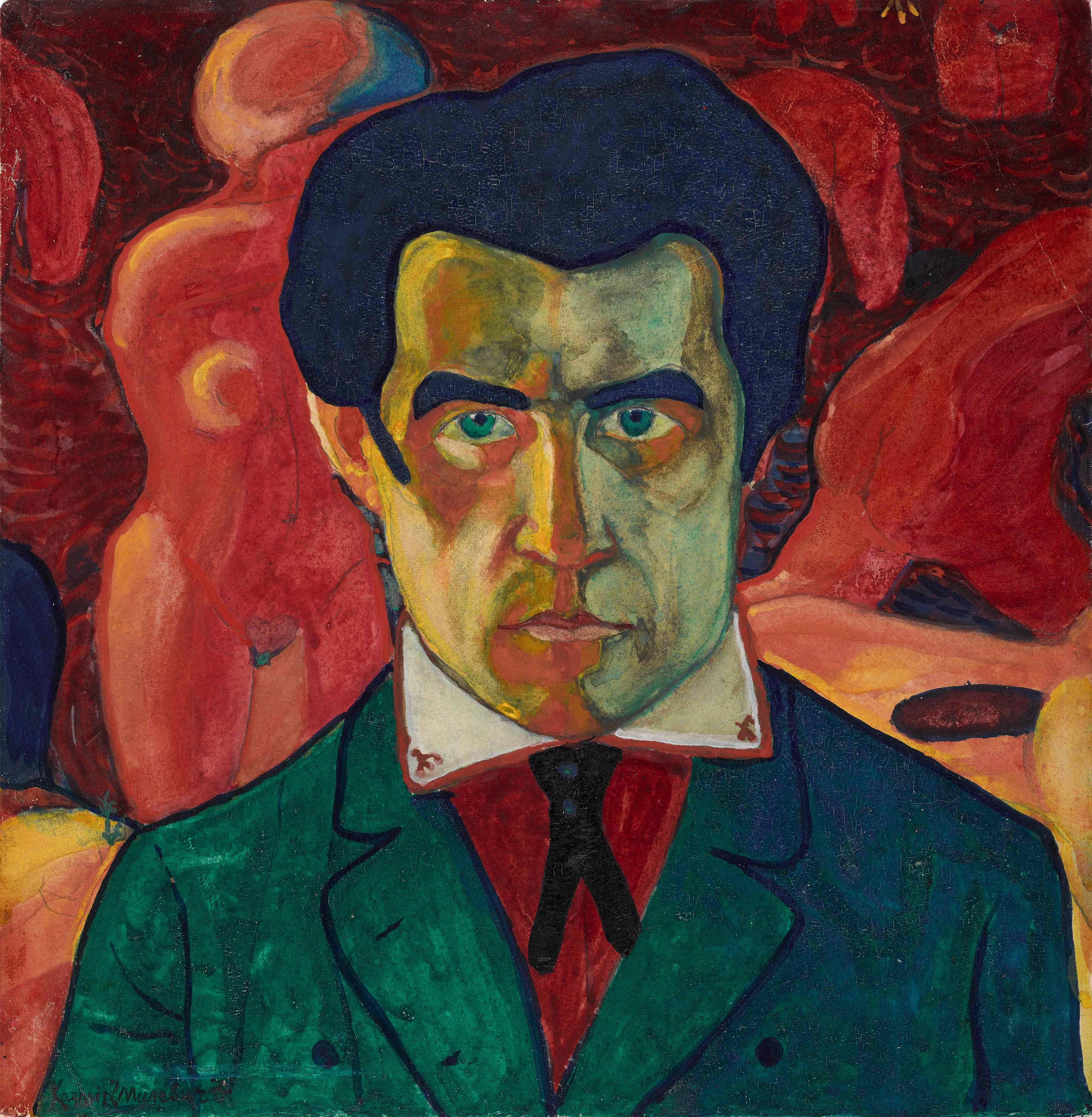

* Kazimir Malevich

Kazimir Severinovich Malevich ; german: Kasimir Malewitsch; pl, Kazimierz Malewicz; russian: Казими́р Севери́нович Мале́вич ; uk, Казимир Северинович Малевич, translit=Kazymyr Severynovych ...

(Kazimierz Malewicz) - painter, pioneer of geometric abstract art and the originator of the avant-garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or ' vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretical ...

, Suprematist

Suprematism (russian: Супремати́зм) is an early twentieth-century art movement focused on the fundamentals of geometry (circles, squares, rectangles), painted in a limited range of colors. The term ''suprematism'' refers to an abstra ...

movement

* Yury Olesha

Yury Karlovich Olesha (russian: Ю́рий Ка́рлович Оле́ша, – 10 May 1960) was a Russian and Soviet novelist. He is considered one of the greatest Russian novelists of the 20th century, one of the few to have succeeded in wri ...

- writer

* Tomasz DƒÖbal

Tomasz Jan Dąbal (; 29 December 1890 – 21 August 1937) was a Polish lawyer, activist of the interwar period and politician. He was the co-founder and the head of state of the Republic of Tarnobrzeg, succeeded by the Second Polish Republic.

...

- communist politician

* Konstantin Rokossovsky

Konstantin Konstantinovich (Xaverevich) Rokossovsky (Russian: –ö–æ–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–Ω—Ç–∏–Ω –ö–æ–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–Ω—Ç–∏–Ω–æ–≤–∏—á –Ý–æ–∫–æ—Å—Å–æ–≤—Å–∫–∏–π; pl, Konstanty Rokossowski; 21 December 1896 ‚Äì 3 August 1968) was a Soviet and Polish officer who becam ...

(Konstanty Rokossowski) - Marshal of the Soviet Union

Marshal of the Soviet Union (russian: –ú–∞—Ä—à–∞–ª –°–æ–≤–µ—Ç—Å–∫–æ–≥–æ –°–æ—é–∑–∞, Marshal sovetskogo soyuza, ) was the highest military rank of the Soviet Union.

The rank of Marshal of the Soviet Union was created in 1935 and abolished in 19 ...

, planner and director of Operation Bagration

Operation Bagration (; russian: Операция Багратио́н, Operatsiya Bagration) was the codename for the 1944 Soviet Byelorussian strategic offensive operation (russian: Белорусская наступательная опР...

(liberation of Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, –Ý–µ—Å–ø—É–±–ª–∏–∫–∞ –ë–µ–ª–∞—Ä—É—Å—å, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

and the eastern Poland)

* Konstantin Tsiolkovsky

Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky (russian: –ö–æ–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–Ω—Ç–∏ÃÅ–Ω –≠–¥—É–∞ÃÅ—Ä–¥–æ–≤–∏—á –¶–∏–æ–ª–∫–æÃÅ–≤—Å–∫–∏–π , , p=k…ônst…ên ≤Ààt ≤in …™d äÀàard…ôv ≤…™t…ï ts…®…êlÀàkofsk ≤…™j , a=Ru-Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.oga; ‚Äì 19 September 1935) ...

(Ciołkowski) - rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entirely fr ...

scientist (with a father of Polish descent)

* Stanislav Kosior Stanislav and variants may refer to:

People

*Stanislav (given name), a Slavic given name with many spelling variations (Stanislaus, Stanislas, Stanisław, etc.)

Places

* Stanislav, a coastal village in Kherson, Ukraine

* Stanislaus County, Cali ...

(Stanisław Kosior) - General Secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party

The Ukrainian Communist Party ( uk, Українська Комуністична Партія, ''Ukrayins’ka Komunistychna Partiya'') was an oppositional political party in Soviet Ukraine, from 1920 until 1925. Its followers were known as Ukap ...

, deputy prime minister of the USSR, and a member of the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (, abbreviated: ), or Politburo ( rus, –ü–æ–ª–∏—Ç–±—é—Ä–æ, p=p…ôl ≤…™tb ≤ äÀàro) was the highest policy-making authority within the Communist Party of the ...

(CPSU), one of the principal so-called architects of the Ukrainian famine of 1932 to 1933

* Karol ≈öwierczewski

Karol Wacław Świerczewski (; callsign ''Walter''; 10 February 1897 Р28 March 1947) was a Polish and Soviet Red Army general and statesman. He was a Bolshevik Party member during the Russian Civil War and a Soviet officer in the wars fough ...

- general, commander of the Polish Second Army

The Polish Second Army ( pl, Druga Armia Wojska Polskiego, 2. AWP for short) was a Polish Army unit formed in the Soviet Union in 1944 as part of the People's Army of Poland. The organization began in August under the command of generals Karol ≈ö ...

during the fighting for western Poland and the Battle of Berlin

The Battle of Berlin, designated as the Berlin Strategic Offensive Operation by the Soviet Union, and also known as the Fall of Berlin, was one of the last major offensives of the European theatre of World War II.

After the Vistula– ...

* Stanislav Poplavsky

Stanislav Gilyarovich Poplavsky (russian: Станислав Гилярович Поплавский, pl, Stanisław Popławski) (22 April 1902 – 10 August 1973) was a general in the Soviet and Polish armies.

Early life

Poplavsky was born in I ...

(Stanisław Popławski) - general, commander of the Polish First Army

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

during the breakthrough of the Pommernstellung (Pomerania Wall) fortification line, securing the Baltic Sea coast, crossing the Odra and Elbe rivers and the battle of Berlin

* Sigizmund Levanevsky

pl, Zygmunt Lewoniewski

, birth_date =

, death_date =

, birth_place = St. Petersburg, Russian empire

, death_place = Arctic Ocean

, image_size =

, allegiance =

, branch = Soviet Army before 1925Soviet Air Force s ...

(Zygmunt Lewoniewski) - aircraft pilot, explorer of the Arctic

* Andrey Vyshinsky

Andrey Yanuaryevich Vyshinsky (russian: Андре́й Януа́рьевич Выши́нский; pl, Andrzej Wyszyński) ( Р22 November 1954) was a Soviet politician, jurist and diplomat.

He is known as a state prosecutor of Joseph ...

(Andriej or Andrzej Wyszyński) - Prosecutor General of the USSR (1934-1939), the legal mastermind of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

's Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: –ë–æ–ª—å—à–æ–π —Ç–µ—Ä—Ä–æ—Ä), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-–π –≥–æ–¥, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

* Arseny Tarkovsky

Arseny Aleksandrovich Tarkovsky (russian: link=no, –ê—Ä—Å–µ–Ω–∏–π –ê–ª–µ–∫—Å–∞–Ω–¥—Ä–æ–≤–∏—á –¢–∞—Ä–∫–æ–≤—Å–∫–∏–π; 27 May 1989) was a Soviet and Russian poet and translator. He was predeceased by his son, film director Andrei Tarkovsky.

Biograph ...

(Tarkowski) - poet and translator (with a father of Polish descent)

* Andrei Tarkovsky

Andrei Arsenyevich Tarkovsky ( rus, –ê–Ω–¥—Ä–µ–π –ê—Ä—Å–µ–Ω—å–µ–≤–∏—á –¢–∞—Ä–∫–æ–≤—Å–∫–∏–π, p=…ênÀàdr ≤ej …êrÀàs ≤en ≤j…™v ≤…™t…ï t…êrÀàkofsk ≤…™j; 4 April 1932 ‚Äì 29 December 1986) was a Russian filmmaker. Widely considered one of the greates ...

(Tarkowski) - film-maker, writer, film editor, film theorist, theatre and opera director (with a paternal grandfather of Polish descent)

* Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, , group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his Symphony No. 1 (Shostakovich), First Symphony in 1926 and was regarded throug ...

(Szostakowicz) - composer (with a paternal grandfather of Polish descent)

* Rostislav Plyatt

Rostislav Yanovich Plyatt (russian: –Ý–æ—Å—Ç–∏—Å–ª–∞–≤ –Ø–Ω–æ–≤–∏—á –ü–ª—è—Ç—Ç; ‚Äî 30 June 1989) was a Soviet and Russian stage and film actor. He was named People's Artist of the USSR in 1961 and awarded the USSR State Prize in 1982.

Biograph ...

- actor (of mixed Polish-Ukrainian descent)

* Mstislav Rostropovich

Mstislav Leopoldovich Rostropovich, (27 March 192727 April 2007) was a Russian cellist and conductor. He is considered by many to be the greatest cellist of the 20th century. In addition to his interpretations and technique, he was wel ...

- cellist and conductor (ethnic Russian, with some Polish descent)

* Rolan Bykov

Rolan Antonovich Bykov (russian: –Ý–æ–ª–∞–Ω –ê–Ω—Ç–æ–Ω–æ–≤–∏—á –ë—ã–∫–æ–≤; October 12, 1929 ‚Äì October 6, 1998) was a Soviet and Russian stage and film actor, director, screenwriter and pedagogue. People's Artist of the USSR (1990).

Early life

R ...

- actor (Polish-Jewish descent)

* Edvard Radzinsky

Edvard Stanislavovich Radzinsky (russian: –≠ÃÅ–¥–≤–∞—Ä–¥ –°—Ç–∞–Ω–∏—Å–ª–∞ÃÅ–≤–æ–≤–∏—á –Ý–∞–¥–∑–∏ÃÅ–Ω—Å–∫–∏–π) (born September 23, 1936) is a Russian playwright, television personality, screenwriter, and the author of more than forty popular history ...

- playwright, TV personality

* Edita Piekha

Edita Piekha (russian: Эди́та Станисла́вовна Пье́ха, ''Edita Stanislavovna Pyekha'', pl, Edyta Piecha, french: Édith-Marie Piecha) is a Soviet and Russian singer and actress of Polish descent. She was the third popular ...

(Edyta Piecha) - singer, born in France, moved to USSR

* Anatoly Sobchak

Anatoly Aleksandrovich Sobchak ( rus, –ê–Ω–∞—Ç–æ–ª–∏–π –ê–ª–µ–∫—Å–∞–Ω–¥—Ä–æ–≤–∏—á –°–æ–±—á–∞–∫, p=…ên…êÀàtol ≤…™j …êl ≤…™Ààksandr…ôv ≤…™t…ï s…êpÀàt…ïak; 10 August 1937 ‚Äì 19 February 2000) was a Soviet and Russian politician, a co-author of the ...

- mayor of Saint Petersburg (mixed Russian-Ukrainian-Polish-Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

*Czech, ...

descent)

* Sergey Yastrzhembsky

Sergey Vladimirovich Yastrzhembsky (russian: Серге́й Владимирович Ястржембский, pl, Siergiej Władimirowicz Jastrzębski), born December 4, 1953, Moscow, is a Russian Federation politician and diplomat.

He was Yelt ...

(Jastrzębski) - Russian politician, President Vladimir Putin’s chief spokesperson on the Second Chechen War

The Second Chechen War (russian: Втора́я чече́нская война́, ) took place in Chechnya and the border regions of the North Caucasus between the Russia, Russian Federation and the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, from Augus ...

, head of the Kremlin’s Information Policy Department, co-ordinating Putin administration's external communications.

* Konstantin Petrzhak

Konstantin Antonovich Petrzhak (alternatively Pietrzak; rus, –ö–æ–Ω—Å—Ç–∞–Ω—Ç–∏ÃÅ–Ω –ê–Ω—Ç–æÃÅ–Ω–æ–≤–∏—á –ü–µÃÅ—Ç—Ä–∂–∞–∫, p=k…ônst…ên ≤Ààt ≤in …ênÀàton…ôv ≤…™t…ï Ààp ≤ed ê…ôk, ; 4 September 1907‚Äì 10 October 1998), , was a Russian physicist o ...

- physicist

See also

*Curzon line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by George Curzon, 1st Marque ...

*Dzierzynszczyzna

Polish National Districts (called in Russian "–ø–æ–ª—Ä–∞–π–æ–Ω—ã", ''polrajony'', an abbreviation for "–ø–æ–ª—å—Å–∫–∏–µ –Ω–∞—Ü–∏–æ–Ω–∞–ª—å–Ω—ã–µ —Ä–∞–π–æ–Ω—ã", "Polish national raions") were in the interbellum period possessing some form of a na ...

*Marchlewszczyzna

Polish National Districts (called in Russian "–ø–æ–ª—Ä–∞–π–æ–Ω—ã", ''polrajony'', an abbreviation for "–ø–æ–ª—å—Å–∫–∏–µ –Ω–∞—Ü–∏–æ–Ω–∞–ª—å–Ω—ã–µ —Ä–∞–π–æ–Ω—ã", "Polish national raions") were in the interbellum period possessing some form of a na ...

*Osadnik

Osadniks ( pl, osadnik/osadnicy, "settler/settlers, colonist/colonists") were veterans of the Polish Army and civilians who were given or sold state land in the ''Kresy'' (current Western Belarus and Western Ukraine) territory ceded to Poland by P ...

* Polonia

*Marian Kropyvnytskyi

Marian Yuliyovych Kropyvnytskyi (born September 8, 1903, in the village of Cherepashyntsi, Russian Empire; died August 16, 1989, in Kyiv, Ukraine) was a Ukrainian artist, painter, and photographer of Polish descent.

Exhibitions

*1931 - Ukrainian ...

References

External links

History of Poles in Kazakhstan

Soviet repressions against Poles and citizens of Poland

{{Polish diaspora Ethnic Poles in the Soviet Union Second Polish Republic Poland in World War II Polish People's Republic Poland–Soviet Union relations

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...