Biography

Early life

Birth and family

Little is known about Plato's early life and education. He belonged to an aristocratic and influential family. According to a disputed tradition, reported by doxographer

Little is known about Plato's early life and education. He belonged to an aristocratic and influential family. According to a disputed tradition, reported by doxographer вАҐ

вАҐ According to the ancient Hellenic tradition, Codrus was said to have been descended from the mythological deity

Plato's mother was Perictione, whose family boasted of a relationship with the famous Athenian

Plato's mother was Perictione, whose family boasted of a relationship with the famous Athenian вАҐ

вАҐ According to some accounts, Ariston tried to force his attentions on Perictione, but failed in his purpose; then the god

вАҐ Diogenes La√Ђrtius, ''Life of Plato'', I

вАҐ The exact time and place of Plato's birth are unknown. Based on ancient sources, most modern scholars believe that he was born in Athens or

Besides Plato himself, Ariston and Perictione had three other children; two sons, Adeimantus and

Besides Plato himself, Ariston and Perictione had three other children; two sons, Adeimantus and 368a

br />вАҐ and presumably brothers of Plato, though some have argued they were uncles. In a scenario in the ''

вАҐ Perictione then married Pyrilampes, her mother's brother,Plato, ''Charmides'

158a

br />вАҐ who had served many times as an ambassador to the Persian court and was a friend of Pericles, the leader of the democratic faction in Athens.Plato, ''Charmides'

158a

br />вАҐ Plutarch, ''Pericles'', IV Pyrilampes had a son from a previous marriage, Demus, who was famous for his beauty. Perictione gave birth to Pyrilampes' second son, Antiphon, the half-brother of Plato, who appears in ''

126c

/ref> In contrast to his reticence about himself, Plato often introduced his distinguished relatives into his dialogues or referred to them with some precision. In addition to Adeimantus and Glaucon in the ''Republic'', Charmides has a dialogue named after him; and Critias speaks in both ''

Name

The fact that the philosopher in his maturity called himself ''Platon'' is indisputable, but the origin of this name remains mysterious. ''Platon'' is app. 21вАУ22

. The sources of Diogenes La√Ђrtius account for this by claiming that his

His true name was supposedly Aristocles (), meaning 'best reputation'. According to Diogenes La√Ђrtius, he was named after his grandfather, as was common in Athenian society. But there is only one inscription of an Aristocles, an early archon of Athens in 605/4 BC. There is no record of a line from Aristocles to Plato's father, Ariston. Recently a scholar has argued that even the name Aristocles for Plato was a much later invention. However, another scholar claims that "there is good reason for not dismissing [the idea that Aristocles was Plato's given name] as a mere invention of his biographers", noting how prevalent that account is in our sources.

His true name was supposedly Aristocles (), meaning 'best reputation'. According to Diogenes La√Ђrtius, he was named after his grandfather, as was common in Athenian society. But there is only one inscription of an Aristocles, an early archon of Athens in 605/4 BC. There is no record of a line from Aristocles to Plato's father, Ariston. Recently a scholar has argued that even the name Aristocles for Plato was a much later invention. However, another scholar claims that "there is good reason for not dismissing [the idea that Aristocles was Plato's given name] as a mere invention of his biographers", noting how prevalent that account is in our sources.

Education

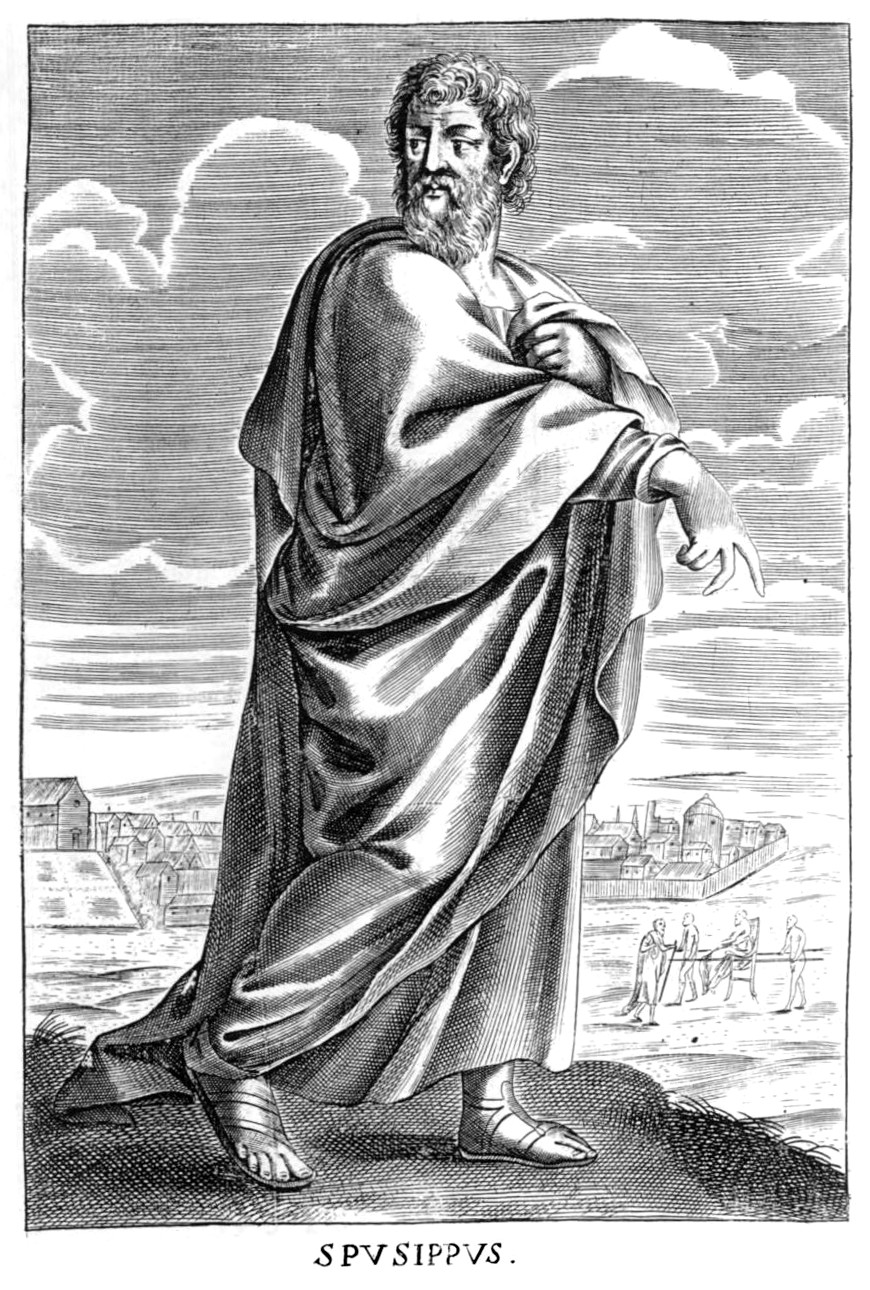

Ancient sources describe him as a bright though modest boy who excelled in his studies. Apuleius informs us that Speusippus praised Plato's quickness of mind and modesty as a boy, and the "first fruits of his youth infused with hard work and love of study".Apuleius, ''De Dogmate Platonis'', 2 His father contributed all which was necessary to give to his son a good education, and, therefore, Plato must have been instructed in grammar, music, and gymnastics by the most distinguished teachers of his time.Diogenes La√Ђrtius, ''Life of Plato'', IVвАҐ Plato invokes Damon of Athens, Damon many times in the ''Republic''. Plato was a wrestler, and Dicaearchus went so far as to say that Plato wrestled at the Isthmian games.Diogenes La√Ђrtius, ''Life of Plato'', V Plato had also attended courses of philosophy; before meeting Socrates, he first became acquainted with Cratylus and the Heraclitean doctrines.Aristotle, ''Metaphysics'',

987a

Ambrose believed that Plato met Jeremiah in Egypt and was influenced by his ideas. Augustine initially accepted this claim, but later rejected it, arguing in ''The City of God'' that "Plato was born a hundred years after Jeremiah prophesied."

Later life and death

Plato may have travelled in Italy, Sicily, Egypt, and Cyrene, Libya, Cyrene. Plato's own statement was that he visited Italy and Sicily at the age of forty and was disgusted by the sensuality of life there. Said to have returned to Athens at the age of forty, Plato founded one of the earliest known organized schools in Western Civilization on a plot of land in the Grove of Hecademus or Academus. This land was named after Academus, an Attica, Attic hero in Greek mythology. In historic Greek times it was adorned with Platanus orientalis, oriental plane and olive plantations

The Academy was a large enclosure of ground about six Stadion (unit of length), stadia (a total of between a kilometer and a half mile) outside of Athens proper. One story is that the name of the comes from the ancient hero, Academus; still another story is that the name came from a supposed former owner of the plot of land, an Athenian citizen whose name was (also) Academus; while yet another account is that it was named after a member of the army of Castor and Pollux, an Regions of ancient Greece#Arcadia, Arcadian named Echedemus. The operated until it was destroyed by Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 84 BC. Many intellectuals were schooled in the , the most prominent one being Aristotle.

Throughout his later life, Plato became entangled with the politics of the city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse. According to Diogenes La√Ђrtius, Plato initially visited Syracuse while it was under the rule of Dionysius I of Syracuse, Dionysius. During this first trip Dionysius's brother-in-law, Dion of Syracuse, became one of Plato's disciples, but the tyrant himself turned against Plato. Plato almost faced death, but he was sold into slavery. Anniceris, a Cyrenaic philosopher, subsequently bought Plato's freedom for twenty Mina (unit), minas, and sent him home. After Dionysius's death, according to Plato's ''Seventh Letter'', Dion requested Plato return to Syracuse to tutor Dionysius II of Syracuse, Dionysius II and guide him to become a philosopher king. Dionysius II seemed to accept Plato's teachings, but he became suspicious of Dion, his uncle. Dionysius expelled Dion and kept Plato against his will. Eventually Plato left Syracuse. Dion would return to overthrow Dionysius and ruled Syracuse for a short time before being usurped by Calippus of Syracuse, Calippus, a fellow disciple of Plato.

According to Seneca, Plato died at the age of 81 on the same day he was born. The Suda indicates that he lived to 82 years, while Neanthes claims an age of 84. A variety of sources have given accounts of his death. One story, based on a mutilated manuscript, suggests Plato died in his bed, whilst a young Thracian girl played the flute to him. Another tradition suggests Plato died at a wedding feast. The account is based on Diogenes La√Ђrtius's reference to an account by Hermippus, a third-century Alexandrian. According to Tertullian, Plato simply died in his sleep.

Plato owned an estate at Iphistiadae, which by will he left to a certain youth named Adeimantus, presumably a younger relative, as Plato had an elder brother or uncle by this name.

Plato may have travelled in Italy, Sicily, Egypt, and Cyrene, Libya, Cyrene. Plato's own statement was that he visited Italy and Sicily at the age of forty and was disgusted by the sensuality of life there. Said to have returned to Athens at the age of forty, Plato founded one of the earliest known organized schools in Western Civilization on a plot of land in the Grove of Hecademus or Academus. This land was named after Academus, an Attica, Attic hero in Greek mythology. In historic Greek times it was adorned with Platanus orientalis, oriental plane and olive plantations

The Academy was a large enclosure of ground about six Stadion (unit of length), stadia (a total of between a kilometer and a half mile) outside of Athens proper. One story is that the name of the comes from the ancient hero, Academus; still another story is that the name came from a supposed former owner of the plot of land, an Athenian citizen whose name was (also) Academus; while yet another account is that it was named after a member of the army of Castor and Pollux, an Regions of ancient Greece#Arcadia, Arcadian named Echedemus. The operated until it was destroyed by Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 84 BC. Many intellectuals were schooled in the , the most prominent one being Aristotle.

Throughout his later life, Plato became entangled with the politics of the city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse. According to Diogenes La√Ђrtius, Plato initially visited Syracuse while it was under the rule of Dionysius I of Syracuse, Dionysius. During this first trip Dionysius's brother-in-law, Dion of Syracuse, became one of Plato's disciples, but the tyrant himself turned against Plato. Plato almost faced death, but he was sold into slavery. Anniceris, a Cyrenaic philosopher, subsequently bought Plato's freedom for twenty Mina (unit), minas, and sent him home. After Dionysius's death, according to Plato's ''Seventh Letter'', Dion requested Plato return to Syracuse to tutor Dionysius II of Syracuse, Dionysius II and guide him to become a philosopher king. Dionysius II seemed to accept Plato's teachings, but he became suspicious of Dion, his uncle. Dionysius expelled Dion and kept Plato against his will. Eventually Plato left Syracuse. Dion would return to overthrow Dionysius and ruled Syracuse for a short time before being usurped by Calippus of Syracuse, Calippus, a fellow disciple of Plato.

According to Seneca, Plato died at the age of 81 on the same day he was born. The Suda indicates that he lived to 82 years, while Neanthes claims an age of 84. A variety of sources have given accounts of his death. One story, based on a mutilated manuscript, suggests Plato died in his bed, whilst a young Thracian girl played the flute to him. Another tradition suggests Plato died at a wedding feast. The account is based on Diogenes La√Ђrtius's reference to an account by Hermippus, a third-century Alexandrian. According to Tertullian, Plato simply died in his sleep.

Plato owned an estate at Iphistiadae, which by will he left to a certain youth named Adeimantus, presumably a younger relative, as Plato had an elder brother or uncle by this name.

Influences

Pythagoras

Although Socrates influenced Plato directly as related in the dialogues, the influence of

Although Socrates influenced Plato directly as related in the dialogues, the influence of Numenius of Apamea, Numenius accepted both Pythagoras and Plato as the two authorities one should follow in philosophy, but he regarded Plato's authority as subordinate to that of Pythagoras, whom he considered to be the source of all true philosophyвАФincluding Plato's own. For Numenius it is just that Plato wrote so many philosophical works, whereas Pythagoras' views were originally passed on only orally.According to R. M. Hare, this influence consists of three points: #The platonic Republic might be related to the idea of "a tightly organized community of like-minded thinkers", like the one established by Pythagoras in Croton. #The idea that mathematics and, generally speaking, abstract thinking is a secure basis for philosophical thinking as well as "for substantial theses in science and morals". #They shared a "mystical approach to the soul and its place in the material world".

Plato and mathematics

Plato may have studied under the mathematician Theodorus of Cyrene, and has a Theaetetus (dialogue), dialogue named for and whose central character is the mathematician Theaetetus (mathematician), Theaetetus. While not a mathematician, Plato was considered an accomplished teacher of mathematics. Eudoxus of Cnidus, the greatest mathematician in Classical Greece, who contributed much of what is found in Euclid's ''Euclid's Elements, Elements'', was taught by Archytas and Plato. Plato helped to distinguish between pure mathematics, pure and applied mathematics by widening the gap between "arithmetic", now called number theory and "logistic", now called arithmetic. In the dialogue ''Timaeus (dialogue), Timaeus'' Plato associated each of the four classical elements (Earth (classical element), earth, Air (classical element), air, Water (classical element), water, and Fire (classical element), fire) with a regular solid (cube, octahedron, icosahedron, and tetrahedron respectively) due to their shape, the so-called Platonic solids. The fifth regular solid, the dodecahedron, was supposed to be the element which made up the heavens.

In the dialogue ''Timaeus (dialogue), Timaeus'' Plato associated each of the four classical elements (Earth (classical element), earth, Air (classical element), air, Water (classical element), water, and Fire (classical element), fire) with a regular solid (cube, octahedron, icosahedron, and tetrahedron respectively) due to their shape, the so-called Platonic solids. The fifth regular solid, the dodecahedron, was supposed to be the element which made up the heavens.

Heraclitus and Parmenides

The two philosophersSocrates

Plato was one of the devoted young followers of

Plato was one of the devoted young followers of Philosophy

Metaphysics

In Plato's dialogues, Socrates and his company of disputants had something to say on many subjects, including several aspects of metaphysics. These include religion and science, human nature, love, and sexuality. More than one dialogue contrasts perception and reality, nature and custom, and body and soul. F. M. Cornford, Francis Cornford identified the "twin pillars of Platonism" as the theory of Forms, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the doctrine of immortality of the soul.The Forms

Aside from being immutable, timeless, changeless, and one over many, the Forms also provide definitions and the standard against which all instances are measured. In the dialogues Socrates regularly asks for the meaning вАУ in the sense of intensional definitions вАУ of a general term (e. g. justice, truth, beauty), and criticizes those who instead give him particular, Extension (semantics), extensional examples, rather than the quality shared by all examples.

There is thus a world of perfect, eternal, and changeless meanings of predicates, the Forms, existing in the Hyperuranion, realm of Being outside of Spacetime, space and time; and the imperfect sensible world of becoming, subjects somehow in Kh√іra, a state between being and nothing, that partakes of the qualities of the Forms, and is its instantiation.

Aside from being immutable, timeless, changeless, and one over many, the Forms also provide definitions and the standard against which all instances are measured. In the dialogues Socrates regularly asks for the meaning вАУ in the sense of intensional definitions вАУ of a general term (e. g. justice, truth, beauty), and criticizes those who instead give him particular, Extension (semantics), extensional examples, rather than the quality shared by all examples.

There is thus a world of perfect, eternal, and changeless meanings of predicates, the Forms, existing in the Hyperuranion, realm of Being outside of Spacetime, space and time; and the imperfect sensible world of becoming, subjects somehow in Kh√іra, a state between being and nothing, that partakes of the qualities of the Forms, and is its instantiation.

The soul

For Plato, as was characteristic of ancient Greek philosophy, the soul was that which gave life. See this brief exchange from the ''Phaedo'': "What is it that, when present in a body, makes it living? вАФ A soul." Another hallmark of Plato's view of the soul is that it is what rules and controls a person's body. Plato uses this observation in the ''Alcibiades'' as evidence that people are their souls. Plato advocates a belief in the immortality of the soul, and several dialogues end with long speeches imagining the afterlife. In the ''Timaeus'', Socrates locates the parts of the soul within the human body: Reason is located in the head, spirit in the top third of the torso, and the appetite in the middle third of the torso, down to the navel. Furthermore, Plato evinces in multiple dialogues (such as the ''Phaedo'' and ''Timaeus'') a belief in the theory of reincarnation. Scholars debate whether he intends the theory to be literally true, however.Epistemology

Plato also discusses several aspects of epistemology. More than one dialogue contrasts knowledge (''episteme'') and opinion (''doxa''). Platonic epistemology, Plato's epistemology involves Socrates (and other characters, such as Timaeus) arguing that knowledge is not Empiricism, empirical, and that it comes from divine insight. The Forms are also responsible for both knowledge or certainty, and are grasped by pure reason. In several dialogues, Socrates inverts the common man's intuition about what is knowable and what is real. Reality is unavailable to those who use their senses. Socrates says that he who sees with his eyes is blind. While most people take the objects of their senses to be real if anything is, Socrates is contemptuous of people who think that something has to be graspable in the hands to be real. In the ''Theaetetus'', he says such people are ''eu amousoi'' (ќµбљЦ бЉДќЉќњѕЕѕГќњќє), an expression that means literally, "happily without the muses". In other words, such people are willingly ignorant, living without divine inspiration and access to higher insights about reality. In Plato's dialogues, Socrates always insists on his ignorance and humility, that I know that I know nothing, he knows nothing, so-called "Irony#Socratic irony, Socratic irony." Several dialogues refute a series of viewpoints, but offer no positive position, thus ending in ''aporia''.Recollection

In several of Plato's dialogues, Socrates promulgates the idea that knowledge is a matter of Anamnesis (philosophy), recollection of things acquainted with before one is born, and not of observation or study. Keeping with the theme of admitting his own ignorance, Socrates regularly complains of his forgetfulness. In the ''Meno'', Socrates uses a geometrical example to expound Plato's view that knowledge in this latter sense is acquired by recollection. Socrates elicits a fact concerning a geometrical construction from a slave boy, who could not have otherwise known the fact (due to the slave boy's lack of education). The knowledge must be of, Socrates concludes, an eternal, non-perceptible Form. In other dialogues, the ''Sophist'', ''Statesman (dialogue), Statesman'', ''Republic'', ''Timaeus'', and the ''Parmenides'', Plato associates knowledge with the apprehension of unchanging Forms and their relationships to one another (which he calls "expertise" in dialectic), including through the processes of ''collection'' and ''division''. More explicitly, Plato himself argues in the ''Timaeus'' that knowledge is always proportionate to the realm from which it is gained. In other words, if one derives one's account of something experientially, because the world of sense is in flux, the views therein attained will be mere opinions. Meanwhile, opinions are characterized by a lack of necessity and stability. On the other hand, if one derives one's account of something by way of the non-sensible Forms, because these Forms are unchanging, so too is the account derived from them. That apprehension of Forms is required for knowledge may be taken to cohere with Plato's theory in the ''Theaetetus'' and ''Meno''. Indeed, the apprehension of Forms may be at the base of the account required for justification, in that it offers Foundationalism, foundational knowledge which itself needs no account, thereby avoiding an infinite regression.Justified true belief

Ethics

Several dialogues discuss ethics including virtue and vice, pleasure and pain, crime and punishment, and justice and medicine. Plato views "The Good" as the supreme Form, somehow existing even "beyond being". Socrates propounded a moral intellectualism which claimed nobody does bad on purpose, and to know what is good results in doing what is good; that knowledge is virtue. In the ''Protagoras'' dialogue it is argued that virtue is innate and cannot be learned. Socrates presents the famous Euthyphro dilemma in the Euthyphro, dialogue of the same name: "Is the piety, pious (:wikt:бљЕѕГќєќњѕВ, ѕДбљЄ бљЕѕГќєќњќљ) loved by the deity, gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?" (Stephanus pagination, 10a)Justice

As above, in the ''Republic'', Plato asks the question, вАЬWhat is justice?вАЭ By means of the Greek term ''dikaiosune'' вАУ a term for вАЬjusticeвАЭ that captures both individual justice and the justice that informs societies, Plato is able not only to inform metaphysics, but also ethics and politics with the question: вАЬWhat is the basis of moral and social obligation?вАЭ Plato's well-known answer rests upon the fundamental responsibility to seek wisdom, wisdom which leads to an understanding of the Form of the Good. Plato further argues that such understanding of Forms produces and ensures the good communal life when ideally structured under a philosopher king in a society with three classes (philosopher kings, guardians, and workers) that neatly mirror his triadic view of the individual soul (reason, spirit, and appetite). In this manner, justice is obtained when knowledge of how to fulfill one's moral and political function in society is put into practice.Politics

The dialogues also discuss politics. Some of Plato's most famous doctrines are contained in the ''Republic'' as well as in the ''Laws (dialogue), Laws'' and the ''Statesman''. Because these opinions are not spoken directly by Plato and vary between dialogues, they cannot be straightforwardly assumed as representing Plato's own views.

Socrates asserts that societies have a tripartite class structure corresponding to the appetite/spirit/reason structure of the individual soul. The appetite/spirit/reason are analogous to the castes of society.

* ''Productive'' (Workers) вАУ the labourers, carpenters, plumbers, masons, merchants, farmers, ranchers, etc. These correspond to the "appetite" part of the soul.

* ''Protective'' (Warriors or Guardians) вАУ those who are adventurous, strong and brave; in the armed forces. These correspond to the "spirit" part of the soul.

* ''Governing'' (Rulers or Philosopher Kings) вАУ those who are intelligent, rational, self-controlled, in love with wisdom, well suited to make decisions for the community. These correspond to the "reason" part of the soul and are very few.

According to this model, the principles of Athenian democracy (as it existed in his day) are rejected as only a few are fit to rule. Instead of rhetoric and persuasion, Socrates says reason and wisdom should govern. As Socrates puts it:

: "Until philosophers rule as kings or those who are now called kings and leading men genuinely and adequately philosophize, that is, until political power and philosophy entirely coincide, while the many natures who at present pursue either one exclusively are forcibly prevented from doing so, cities will have no rest from evils,... nor, I think, will the human race."

Socrates describes these "philosopher kings" as "those who love the sight of truth" and supports the idea with the analogy of a captain and his ship or a doctor and his medicine. According to him, sailing and health are not things that everyone is qualified to practice by nature. A large part of the ''Republic'' then addresses how the educational system should be set up to produce these philosopher kings.

In addition, the ideal city is used as an image to illuminate the state of one's soul, or the Free will, will, reason, and Interpersonal attraction, desires combined in the human body. Socrates is attempting to make an image of a rightly ordered human, and then later goes on to describe the different kinds of humans that can be observed, from tyrants to lovers of money in various kinds of cities. The ideal city is not promoted, but only used to magnify the different kinds of individual humans and the state of their soul. However, the philosopher king image was used by many after Plato to justify their personal political beliefs. The philosophic soul according to Socrates has reason, will, and desires united in virtuous harmony. A philosopher has the moderate love for wisdom and the courage to act according to wisdom. Wisdom is knowledge about the Goodness and value theory, Good or the right relations between all that Existence, exists.

Wherein it concerns states and rulers, Socrates asks which is betterвАФa bad democracy or a country reigned by a tyrant. He argues that it is better to be ruled by a bad tyrant, than by a bad democracy (since here all the people are now responsible for such actions, rather than one individual committing many bad deeds.) This is emphasised within the ''Republic'' as Socrates describes the event of mutiny on board a ship. Socrates suggests the ship's crew to be in line with the democratic rule of many and the captain, although inhibited through ailments, the tyrant. Socrates' description of this event is parallel to that of democracy within the state and the inherent problems that arise.

According to Socrates, a state made up of different kinds of souls will, overall, decline from an aristocracy (rule by the best) to a timocracy (rule by the honourable), then to an oligarchy (rule by the few), then to a democracy (rule by the people), and finally to tyranny (rule by one person, rule by a tyrant). Aristocracy in the sense of government (politeia) is advocated in Plato's Republic. This regime is ruled by a philosopher king, and thus is grounded on wisdom and reason.

The aristocratic state, and the man whose nature corresponds to it, are the objects of Plato's analyses throughout much of the ''Republic'', as opposed to the other four types of states/men, who are discussed later in his work. In Book VIII, Socrates states in order the other four imperfect societies with a description of the state's structure and individual character. In timocracy, the ruling class is made up primarily of those with a warrior-like character. Oligarchy is made up of a society in which wealth is the criterion of merit and the wealthy are in control. In democracy, the state bears resemblance to ancient Athens with traits such as equality of political opportunity and freedom for the individual to do as he likes. Democracy then degenerates into tyranny from the conflict of rich and poor. It is characterized by an undisciplined society existing in chaos, where the tyrant rises as a popular champion leading to the formation of his private army and the growth of oppression.

The dialogues also discuss politics. Some of Plato's most famous doctrines are contained in the ''Republic'' as well as in the ''Laws (dialogue), Laws'' and the ''Statesman''. Because these opinions are not spoken directly by Plato and vary between dialogues, they cannot be straightforwardly assumed as representing Plato's own views.

Socrates asserts that societies have a tripartite class structure corresponding to the appetite/spirit/reason structure of the individual soul. The appetite/spirit/reason are analogous to the castes of society.

* ''Productive'' (Workers) вАУ the labourers, carpenters, plumbers, masons, merchants, farmers, ranchers, etc. These correspond to the "appetite" part of the soul.

* ''Protective'' (Warriors or Guardians) вАУ those who are adventurous, strong and brave; in the armed forces. These correspond to the "spirit" part of the soul.

* ''Governing'' (Rulers or Philosopher Kings) вАУ those who are intelligent, rational, self-controlled, in love with wisdom, well suited to make decisions for the community. These correspond to the "reason" part of the soul and are very few.

According to this model, the principles of Athenian democracy (as it existed in his day) are rejected as only a few are fit to rule. Instead of rhetoric and persuasion, Socrates says reason and wisdom should govern. As Socrates puts it:

: "Until philosophers rule as kings or those who are now called kings and leading men genuinely and adequately philosophize, that is, until political power and philosophy entirely coincide, while the many natures who at present pursue either one exclusively are forcibly prevented from doing so, cities will have no rest from evils,... nor, I think, will the human race."

Socrates describes these "philosopher kings" as "those who love the sight of truth" and supports the idea with the analogy of a captain and his ship or a doctor and his medicine. According to him, sailing and health are not things that everyone is qualified to practice by nature. A large part of the ''Republic'' then addresses how the educational system should be set up to produce these philosopher kings.

In addition, the ideal city is used as an image to illuminate the state of one's soul, or the Free will, will, reason, and Interpersonal attraction, desires combined in the human body. Socrates is attempting to make an image of a rightly ordered human, and then later goes on to describe the different kinds of humans that can be observed, from tyrants to lovers of money in various kinds of cities. The ideal city is not promoted, but only used to magnify the different kinds of individual humans and the state of their soul. However, the philosopher king image was used by many after Plato to justify their personal political beliefs. The philosophic soul according to Socrates has reason, will, and desires united in virtuous harmony. A philosopher has the moderate love for wisdom and the courage to act according to wisdom. Wisdom is knowledge about the Goodness and value theory, Good or the right relations between all that Existence, exists.

Wherein it concerns states and rulers, Socrates asks which is betterвАФa bad democracy or a country reigned by a tyrant. He argues that it is better to be ruled by a bad tyrant, than by a bad democracy (since here all the people are now responsible for such actions, rather than one individual committing many bad deeds.) This is emphasised within the ''Republic'' as Socrates describes the event of mutiny on board a ship. Socrates suggests the ship's crew to be in line with the democratic rule of many and the captain, although inhibited through ailments, the tyrant. Socrates' description of this event is parallel to that of democracy within the state and the inherent problems that arise.

According to Socrates, a state made up of different kinds of souls will, overall, decline from an aristocracy (rule by the best) to a timocracy (rule by the honourable), then to an oligarchy (rule by the few), then to a democracy (rule by the people), and finally to tyranny (rule by one person, rule by a tyrant). Aristocracy in the sense of government (politeia) is advocated in Plato's Republic. This regime is ruled by a philosopher king, and thus is grounded on wisdom and reason.

The aristocratic state, and the man whose nature corresponds to it, are the objects of Plato's analyses throughout much of the ''Republic'', as opposed to the other four types of states/men, who are discussed later in his work. In Book VIII, Socrates states in order the other four imperfect societies with a description of the state's structure and individual character. In timocracy, the ruling class is made up primarily of those with a warrior-like character. Oligarchy is made up of a society in which wealth is the criterion of merit and the wealthy are in control. In democracy, the state bears resemblance to ancient Athens with traits such as equality of political opportunity and freedom for the individual to do as he likes. Democracy then degenerates into tyranny from the conflict of rich and poor. It is characterized by an undisciplined society existing in chaos, where the tyrant rises as a popular champion leading to the formation of his private army and the growth of oppression.

Art and poetry

Several dialogues tackle questions about art, including rhetoric and rhapsody. Socrates says that poetry is inspired by the muses, and is not rational. He speaks approvingly of this, and other forms of divine madness (drunkenness, eroticism, and dreaming) in the ''Phaedrus'', and yet in the ''Republic'' wants to outlaw Homer's great poetry, and laughter as well. In ''Ion (dialogue), Ion'', Socrates gives no hint of the disapproval of Homer that he expresses in the ''Republic''. The dialogue ''Ion'' suggests that Homer's ''Iliad'' functioned in the ancient Greek world as the Bible does today in the modern Christian world: as divinely inspired literature that can provide moral guidance, if only it can be properly interpreted.Rhetoric

Scholars often view Plato's philosophy as at odds with rhetoric due to his criticisms of rhetoric in the ''Gorgias (dialogue), Gorgias'' and his ambivalence toward rhetoric expressed in the ''Phaedrus (dialogue), Phaedrus''. But other contemporary researchers contest the idea that Plato despised rhetoric and instead view his dialogues as a dramatization of complex rhetorical principles.Unwritten doctrines

For a long time, Plato's unwritten doctrines had been controversial. Many modern books on Plato seem to diminish its importance; nevertheless, the first important witness who mentions its existence is Aristotle, who in his ''Physics (Aristotle), Physics'' writes: "It is true, indeed, that the account he gives there [i.e. in ''Timaeus''] of the participant is different from what he says in his so-called ''unwritten teachings'' ()." The term "" literally means ''unwritten doctrines'' or ''unwritten dogmas'' and it stands for the most fundamental metaphysical teaching of Plato, which he disclosed only orally, and some say only to his most trusted fellows, and which he may have kept secret from the public. The importance of the unwritten doctrines does not seem to have been seriously questioned before the 19th century.

A reason for not revealing it to everyone is partially discussed in ''Phaedrus'' where Plato criticizes the written transmission of knowledge as faulty, favouring instead the spoken ''logos'': "he who has knowledge of the just and the good and beautiful ... will not, when in earnest, write them in ink, sowing them through a pen with words, which cannot defend themselves by argument and cannot teach the truth effectually." The same argument is repeated in Plato's ''Seventh Letter'': "every serious man in dealing with really serious subjects carefully avoids writing." In the same letter he writes: "I can certainly declare concerning all these writers who claim to know the subjects that I seriously study ... there does not exist, nor will there ever exist, any treatise of mine dealing therewith." Such secrecy is necessary in order not "to expose them to unseemly and degrading treatment".

It is, however, said that Plato once disclosed this knowledge to the public in his lecture ''On the Good'' (), in which the Good () is identified with the One (the Unity, ), the fundamental ontological principle. The content of this lecture has been transmitted by several witnesses. Aristoxenus describes the event in the following words: "Each came expecting to learn something about the things that are generally considered good for men, such as wealth, good health, physical strength, and altogether a kind of wonderful happiness. But when the mathematical demonstrations came, including numbers, geometrical figures and astronomy, and finally the statement Good is One seemed to them, I imagine, utterly unexpected and strange; hence some belittled the matter, while others rejected it." Simplicius of Cilicia, Simplicius quotes Alexander of Aphrodisias, who states that "according to Plato, the first principles of everything, including the Forms themselves are One and Indefinite Duality (), which he called Large and Small ()", and Simplicius reports as well that "one might also learn this from Speusippus and Xenocrates and the others who were present at Plato's lecture on the Good".see .

Their account is in full agreement with Aristotle's description of Plato's metaphysical doctrine. In ''Metaphysics (Aristotle), Metaphysics'' he writes: "Now since the Forms are the causes of everything else, he [i.e. Plato] supposed that their elements are the elements of all things. Accordingly, the material principle is the Great and Small [i.e. the Dyad], and the essence is the One (), since the numbers are derived from the Great and Small by participation in the One".''Metaphysics'' 987b "From this account it is clear that he only employed two causes: that of the essence, and the material cause; for the Forms are the cause of the essence in everything else, and the One is the cause of it in the Forms. He also tells us what the material substrate is of which the Forms are predicated in the case of sensible things, and the One in that of the FormsвАФthat it is this the duality (the Dyad, ), the Great and Small (). Further, he assigned to these two elements respectively the causation of good and of evil".

The most important aspect of this interpretation of Plato's metaphysics is the continuity between his teaching and the Neoplatonic interpretation of Plotinus or Ficino which has been considered erroneous by many but may in fact have been directly influenced by oral transmission of Plato's doctrine. A modern scholar who recognized the importance of the unwritten doctrine of Plato was Heinrich Gomperz who described it in his speech during the 7th International Congress of Philosophy in 1930. All the sources related to the have been collected by Konrad Gaiser and published as ''Testimonia Platonica''. These sources have subsequently been interpreted by scholars from the German ''T√Љbingen School of interpretation'' such as Hans Joachim Kr√§mer or Thomas A. Szlez√°k.

For a long time, Plato's unwritten doctrines had been controversial. Many modern books on Plato seem to diminish its importance; nevertheless, the first important witness who mentions its existence is Aristotle, who in his ''Physics (Aristotle), Physics'' writes: "It is true, indeed, that the account he gives there [i.e. in ''Timaeus''] of the participant is different from what he says in his so-called ''unwritten teachings'' ()." The term "" literally means ''unwritten doctrines'' or ''unwritten dogmas'' and it stands for the most fundamental metaphysical teaching of Plato, which he disclosed only orally, and some say only to his most trusted fellows, and which he may have kept secret from the public. The importance of the unwritten doctrines does not seem to have been seriously questioned before the 19th century.

A reason for not revealing it to everyone is partially discussed in ''Phaedrus'' where Plato criticizes the written transmission of knowledge as faulty, favouring instead the spoken ''logos'': "he who has knowledge of the just and the good and beautiful ... will not, when in earnest, write them in ink, sowing them through a pen with words, which cannot defend themselves by argument and cannot teach the truth effectually." The same argument is repeated in Plato's ''Seventh Letter'': "every serious man in dealing with really serious subjects carefully avoids writing." In the same letter he writes: "I can certainly declare concerning all these writers who claim to know the subjects that I seriously study ... there does not exist, nor will there ever exist, any treatise of mine dealing therewith." Such secrecy is necessary in order not "to expose them to unseemly and degrading treatment".

It is, however, said that Plato once disclosed this knowledge to the public in his lecture ''On the Good'' (), in which the Good () is identified with the One (the Unity, ), the fundamental ontological principle. The content of this lecture has been transmitted by several witnesses. Aristoxenus describes the event in the following words: "Each came expecting to learn something about the things that are generally considered good for men, such as wealth, good health, physical strength, and altogether a kind of wonderful happiness. But when the mathematical demonstrations came, including numbers, geometrical figures and astronomy, and finally the statement Good is One seemed to them, I imagine, utterly unexpected and strange; hence some belittled the matter, while others rejected it." Simplicius of Cilicia, Simplicius quotes Alexander of Aphrodisias, who states that "according to Plato, the first principles of everything, including the Forms themselves are One and Indefinite Duality (), which he called Large and Small ()", and Simplicius reports as well that "one might also learn this from Speusippus and Xenocrates and the others who were present at Plato's lecture on the Good".see .

Their account is in full agreement with Aristotle's description of Plato's metaphysical doctrine. In ''Metaphysics (Aristotle), Metaphysics'' he writes: "Now since the Forms are the causes of everything else, he [i.e. Plato] supposed that their elements are the elements of all things. Accordingly, the material principle is the Great and Small [i.e. the Dyad], and the essence is the One (), since the numbers are derived from the Great and Small by participation in the One".''Metaphysics'' 987b "From this account it is clear that he only employed two causes: that of the essence, and the material cause; for the Forms are the cause of the essence in everything else, and the One is the cause of it in the Forms. He also tells us what the material substrate is of which the Forms are predicated in the case of sensible things, and the One in that of the FormsвАФthat it is this the duality (the Dyad, ), the Great and Small (). Further, he assigned to these two elements respectively the causation of good and of evil".

The most important aspect of this interpretation of Plato's metaphysics is the continuity between his teaching and the Neoplatonic interpretation of Plotinus or Ficino which has been considered erroneous by many but may in fact have been directly influenced by oral transmission of Plato's doctrine. A modern scholar who recognized the importance of the unwritten doctrine of Plato was Heinrich Gomperz who described it in his speech during the 7th International Congress of Philosophy in 1930. All the sources related to the have been collected by Konrad Gaiser and published as ''Testimonia Platonica''. These sources have subsequently been interpreted by scholars from the German ''T√Љbingen School of interpretation'' such as Hans Joachim Kr√§mer or Thomas A. Szlez√°k.

Themes of Plato's dialogues

Trial of Socrates

The trial of Socrates and his death sentence is the central, unifying event of Plato's dialogues. It is relayed in the dialogues Apology (Plato), ''Apology'', ''Crito'', and ''Phaedo''. ''Apology'' is Socrates' defence speech, and ''Crito'' and ''Phaedo'' take place in prison after the conviction.

''Apology'' is among the most frequently read of Plato's works. In the ''Apology'', Socrates tries to dismiss rumours that he is a sophism, sophist and defends himself against charges of disbelief in the gods and corruption of the young. Socrates insists that long-standing slander will be the real cause of his demise, and says the legal charges are essentially false. Socrates famously denies being wise, and explains how his life as a philosopher was launched by the Oracle at Delphi. He says that his quest to resolve the riddle of the oracle put him at odds with his fellow man, and that this is the reason he has been mistaken for a menace to the city-state of Athens.

In ''Apology'', Socrates is presented as mentioning Plato by name as one of those youths close enough to him to have been corrupted, if he were in fact guilty of corrupting the youth, and questioning why their fathers and brothers did not step forward to testify against him if he was indeed guilty of such a crime. Later, Plato is mentioned along with Crito, Critobolus, and Apollodorus as offering to pay a fine of 30 Mina (unit), minas on Socrates' behalf, in lieu of the death penalty proposed by Meletus. In the ''Phaedo'', the title character lists those who were in attendance at the prison on Socrates' last day, explaining Plato's absence by saying, "Plato was ill".

The trial of Socrates and his death sentence is the central, unifying event of Plato's dialogues. It is relayed in the dialogues Apology (Plato), ''Apology'', ''Crito'', and ''Phaedo''. ''Apology'' is Socrates' defence speech, and ''Crito'' and ''Phaedo'' take place in prison after the conviction.

''Apology'' is among the most frequently read of Plato's works. In the ''Apology'', Socrates tries to dismiss rumours that he is a sophism, sophist and defends himself against charges of disbelief in the gods and corruption of the young. Socrates insists that long-standing slander will be the real cause of his demise, and says the legal charges are essentially false. Socrates famously denies being wise, and explains how his life as a philosopher was launched by the Oracle at Delphi. He says that his quest to resolve the riddle of the oracle put him at odds with his fellow man, and that this is the reason he has been mistaken for a menace to the city-state of Athens.

In ''Apology'', Socrates is presented as mentioning Plato by name as one of those youths close enough to him to have been corrupted, if he were in fact guilty of corrupting the youth, and questioning why their fathers and brothers did not step forward to testify against him if he was indeed guilty of such a crime. Later, Plato is mentioned along with Crito, Critobolus, and Apollodorus as offering to pay a fine of 30 Mina (unit), minas on Socrates' behalf, in lieu of the death penalty proposed by Meletus. In the ''Phaedo'', the title character lists those who were in attendance at the prison on Socrates' last day, explaining Plato's absence by saying, "Plato was ill".

The trial in other dialogues

If Plato's important dialogues do not refer to Socrates' execution explicitly, they allude to it, or use characters or themes that play a part in it. Five dialogues foreshadow the trial: In the ''Theaetetus'' and the ''Euthyphro'' Socrates tells people that he is about to face corruption charges. In the ''Meno'', one of the men who brings legal charges against Socrates, Anytus, warns him about the trouble he may get into if he does not stop criticizing important people. In the ''Gorgias'', Socrates says that his trial will be like a doctor prosecuted by a cook who asks a jury of children to choose between the doctor's bitter medicine and the cook's tasty treats. In the ''Republic'', Socrates explains why an enlightened man (presumably himself) will stumble in a courtroom situation. Plato's support of aristocracy and distrust of democracy is also taken to be partly rooted in a democracy having killed Socrates. In the ''Protagoras'', Socrates is a guest at the home of Callias III, Callias, son of Hipponicus, a man whom Socrates disparages in the ''Apology'' as having wasted a great amount of money on sophists' fees. Two other important dialogues, the ''Symposium (Plato), Symposium'' and the ''Phaedrus (Plato), Phaedrus'', are linked to the main storyline by characters. In the ''Apology'', Socrates says Aristophanes slandered him in a comic play, and blames him for causing his bad reputation, and ultimately, his death. In the ''Symposium'', the two of them are drinking together with other friends. The character Phaedrus is linked to the main story line by character (Phaedrus is also a participant in the ''Symposium'' and the ''Protagoras'') and by theme (the philosopher as divine emissary, etc.) The ''Protagoras'' is also strongly linked to the ''Symposium'' by characters: all of the formal speakers at the ''Symposium'' (with the exception of Aristophanes) are present at the home of Callias in that dialogue. Charmides and his guardian Critias are present for the discussion in the ''Protagoras''. Examples of characters crossing between dialogues can be further multiplied. The ''Protagoras'' contains the largest gathering of Socratic associates. In the dialogues Plato is most celebrated and admired for, Socrates is concerned with human and political virtue, has a distinctive personality, and friends and enemies who "travel" with him from dialogue to dialogue. This is not to say that Socrates is consistent: a man who is his friend in one dialogue may be an adversary or subject of his mockery in another. For example, Socrates praises the wisdom of Euthyphro (prophet), Euthyphro many times in the ''Cratylus (dialogue), Cratylus'', but makes him look like a fool in the ''Euthyphro''. He disparages sophists generally, and Prodicus specifically in the ''Apology'', whom he also slyly jabs in the ''Cratylus'' for charging the hefty fee of fifty drachmas for a course on language and grammar. However, Socrates tells Theaetetus in his namesake dialogue that he admires Prodicus and has directed many pupils to him. Socrates' ideas are also not consistent within or between or among dialogues.Allegories

''Mythos'' and ''logos'' are terms that evolved throughout classical Greek history. In the times of Homer and Hesiod (i.e., the 8th century BC) they were essentially synonyms, and contained the meaning of 'tale' or 'history'. Later came historians like Herodotus and Thucydides, as well as philosophers like Heraclitus and Parmenides and other Presocratics who introduced a distinction between both terms; mythos became more a ''nonverifiable account'', and logos a ''rational account''. It may seem that Plato, being a disciple of Socrates and a strong partisan of philosophy based on ''logos'', should have avoided the use of myth-telling. Instead, he made abundant use of it. This fact has produced analytical and interpretative work, in order to clarify the reasons and purposes for that use. Furthermore, Plato himself often oscillates between calling one and the same thing a ''muthos'' and a ''logos'', revealing a preference for the earlier view that the two terms are synonyms. Plato, in general, distinguished between three types of myth. First, there were the false myths, like those based on stories of gods subject to passions and sufferings, because reason teaches that God is perfect. Then came the myths based on true reasoning, and therefore also true. Finally, there were those non-verifiable because beyond of human reason, but containing some truth in them. Regarding the subjects of Plato's myths, they are of two types, those dealing with the origin of the universe, and those about morals and the origin and fate of the soul. It is generally agreed that the main purpose for Plato in using myths was didactic. He considered that only a few people were capable or interested in following a reasoned philosophical discourse, but men in general are attracted by stories and tales. Consequently, then, he used the myth to convey the conclusions of the philosophical reasoning. Some of Plato's myths were based in traditional ones, others were modifications of them, and finally, he also invented altogether new myths. Notable examples include the story of Atlantis, the Myth of Er, and the Allegory of the Cave.The Cave

The theory of Forms is most famously captured in his Allegory of the Cave, and more explicitly in his analogy of the sun and Analogy of the divided line, the divided line. The Allegory of the Cave is a paradoxical analogy wherein Socrates argues that the invisible world is the most intelligible (''noeton'') and that the visible world (''(h)oraton'') is the least knowable, and the most obscure.

Socrates says in the ''Republic'' that people who take the sun-lit world of the senses to be good and real are living pitifully in a den of evil and ignorance. Socrates admits that few climb out of the den, or cave of ignorance, and those who do, not only have a terrible struggle to attain the heights, but when they go back down for a visit or to help other people up, they find themselves objects of scorn and ridicule.

According to Socrates, physical objects and physical events are "shadows" of their ideal or perfect forms, and exist only to the extent that they instantiate the perfect versions of themselves. Just as shadows are temporary, inconsequential epiphenomena produced by physical objects, physical objects are themselves fleeting phenomena caused by more substantial causes, the ideals of which they are mere instances. For example, Socrates thinks that perfect justice exists (although it is not clear where) and his own trial would be a cheap copy of it.

The Allegory of the Cave is intimately connected to his political ideology, that only people who have climbed out of the cave and cast their eyes on a vision of goodness are fit to rule. Socrates claims that the enlightened men of society must be forced from their divine contemplation and be compelled to run the city according to their lofty insights. Thus is born the idea of the "philosopher king, philosopher-king", the wise person who accepts the power thrust upon him by the people who are wise enough to choose a good master. This is the main thesis of Socrates in the ''Republic'', that the most wisdom the masses can muster is the wise choice of a ruler.

The theory of Forms is most famously captured in his Allegory of the Cave, and more explicitly in his analogy of the sun and Analogy of the divided line, the divided line. The Allegory of the Cave is a paradoxical analogy wherein Socrates argues that the invisible world is the most intelligible (''noeton'') and that the visible world (''(h)oraton'') is the least knowable, and the most obscure.

Socrates says in the ''Republic'' that people who take the sun-lit world of the senses to be good and real are living pitifully in a den of evil and ignorance. Socrates admits that few climb out of the den, or cave of ignorance, and those who do, not only have a terrible struggle to attain the heights, but when they go back down for a visit or to help other people up, they find themselves objects of scorn and ridicule.

According to Socrates, physical objects and physical events are "shadows" of their ideal or perfect forms, and exist only to the extent that they instantiate the perfect versions of themselves. Just as shadows are temporary, inconsequential epiphenomena produced by physical objects, physical objects are themselves fleeting phenomena caused by more substantial causes, the ideals of which they are mere instances. For example, Socrates thinks that perfect justice exists (although it is not clear where) and his own trial would be a cheap copy of it.

The Allegory of the Cave is intimately connected to his political ideology, that only people who have climbed out of the cave and cast their eyes on a vision of goodness are fit to rule. Socrates claims that the enlightened men of society must be forced from their divine contemplation and be compelled to run the city according to their lofty insights. Thus is born the idea of the "philosopher king, philosopher-king", the wise person who accepts the power thrust upon him by the people who are wise enough to choose a good master. This is the main thesis of Socrates in the ''Republic'', that the most wisdom the masses can muster is the wise choice of a ruler.

Ring of Gyges

A ring that could make one invisible, the Ring of Gyges, is proposed in the ''Republic'' by the character of Glaucon, and considered by the rest of the characters for its ethical consequences, whether an individual possessing it would be most happy abstaining or doing injustice.Chariot

He also compares the soul (psyche (psychology), ''psyche'') to a Chariot Allegory, chariot. In this allegory he introduces a Plato's tripartite theory of soul, triple soul composed of a charioteer and two horses. The charioteer is a symbol of the intellectual and logical part of the soul (Logos, ''logistikon''), and the two horses represent the moral virtues (Thymos, ''thymoeides'') and passionate instincts (''epithymetikon''), respectively, to illustrate the conflict between them.Dialectic

Socrates employs a Socratic method, dialectic method which proceeds by Socratic questioning, questioning. The role of dialectic in Plato's thought is contested but there are two main interpretations: a type of reasoning and a method of intuition. Simon Blackburn adopts the first, saying that Plato's dialectic is "the process of eliciting the truth by means of questions aimed at opening out what is already implicitly known, or at exposing the contradictions and muddles of an opponent's position." A similar interpretation has been put forth by Louis Hartz, who compares Plato's dialectic to that of Hegel. According to this view, opposing arguments improve upon each other, and prevailing opinion is shaped by the synthesis of many conflicting ideas over time. Each new idea exposes a flaw in the accepted model, and the epistemological substance of the debate continually approaches the truth. Hartz's is a teleological interpretation at the core, in which philosophers will ultimately exhaust the available body of knowledge and thus reach "the end of history." Karl Popper, on the other hand, claims that dialectic is the art of intuition for "visualising the divine originals, the Forms or Ideas, of unveiling the Great Mystery behind the common man's everyday world of appearances."Family

Plato often discusses the father-son relationship and the question of whether a father's interest in his sons has much to do with how well his sons turn out. In ancient Athens, a boy was socially located by his family identity, and Plato often refers to his characters in terms of their paternal and fraternal relationships. Socrates was not a family man, and saw himself as the son of his mother, who was apparently a midwife. A divine Fatalism, fatalist, Socrates mocks men who spent exorbitant fees on tutors and trainers for their sons, and repeatedly ventures the idea that good character is a gift from the gods. Plato's dialogue ''Crito'' reminds Socrates that orphans are at the mercy of chance, but Socrates is unconcerned. In the ''Theaetetus'', he is found recruiting as a disciple a young man whose inheritance has been squandered. Socrates twice compares the relationship of the older man and his Athenian pederasty, boy lover to the father-son relationship, and in the ''Phaedo'', Socrates' disciples, towards whom he displays more concern than his biological sons, say they will feel "fatherless" when he is gone. Though Plato Plato's views on women, agreed with Aristotle that women were inferior to men, in the fourth book of the ''Republic'' the character of Socrates says this was only because of ''nomos'' or custom and not because of nature, and thus women needed ''paidia'', rearing or education to be equal to men. In the "merely probable tale" of the eponymous character in the ''Timaeus'', unjust men who live corrupted lives would be reincarnated as women or various animal kinds.Narration

Plato never presents himself as a participant in any of the dialogues, and with the exception of the ''Apology'', there is no suggestion that he heard any of the dialogues firsthand. Some dialogues have no narrator but have a pure "dramatic" form (examples: ''Meno'', ''Gorgias'', ''Phaedrus'', ''Crito'', ''Euthyphro''), some dialogues are narrated by Socrates, wherein he speaks in first person (examples: ''Lysis (dialogue), Lysis'', ''Charmides'', ''Republic''). One dialogue, ''Protagoras'', begins in dramatic form but quickly proceeds to Socrates' narration of a conversation he had previously with the sophist for whom the dialogue is named; this narration continues uninterrupted till the dialogue's end. Two dialogues ''Phaedo'' and ''Symposium'' also begin in dramatic form but then proceed to virtually uninterrupted narration by followers of Socrates. ''Phaedo'', an account of Socrates' final conversation and hemlock drinking, is narrated by Phaedo to Echecrates in a foreign city not long after the execution took place. The ''Symposium'' is narrated by Apollodorus, a Socratic disciple, apparently to Glaucon. Apollodorus assures his listener that he is recounting the story, which took place when he himself was an infant, not from his own memory, but as remembered by Aristodemus, who told him the story years ago. The ''Theaetetus'' is a peculiar case: a dialogue in dramatic form embedded within another dialogue in dramatic form. In the beginning of the ''Theaetetus'', Euclid of Megara, Euclides says that he compiled the conversation from notes he took based on what Socrates told him of his conversation with the title character. The rest of the ''Theaetetus'' is presented as a "book" written in dramatic form and read by one of Euclides' slaves. Some scholars take this as an indication that Plato had by this date wearied of the narrated form. With the exception of the ''Theaetetus'', Plato gives no explicit indication as to how these orally transmitted conversations came to be written down.History of Plato's dialogues

Thirty-five dialogues and thirteen letters (the Epistles (Plato), ''Epistles'') have traditionally been ascribed to Plato, though modern scholarship doubts the authenticity of at least some of these. Plato's writings have been published in several fashions; this has led to several conventions regarding the naming and referencing of Plato's texts.

The usual system for making unique references to sections of the text by Plato derives from a 16th-century edition of Plato's works by Henri Estienne, Henricus Stephanus known as Stephanus pagination.

One tradition regarding the arrangement of Plato's texts is according to tetralogy, tetralogies. This scheme is ascribed by Diogenes La√Ђrtius to an ancient scholar and court astrologer to Tiberius named Thrasyllus of Mendes, Thrasyllus. The list includes works of doubtful authenticity (written in italic), and includes the Letters.

*1st tetralogy

**Euthyphro, Apology (Plato), Apology, Crito, Phaedo

*2nd tetralogy

**Cratylus (dialogue), Cratylus, Theaetetus (dialogue), Theatetus, Sophist (dialogue), Sophist, Statesman (dialogue), Statesman

*3nd tetralogy

**Parmenides (dialogue), Parmenides, Philebus, Symposium (Plato), Symposium, Phaedrus (dialogue), Phaedrus

*4th tetralogy

**First Alcibiades, Alcibiades I, ''Second Alcibiades, Alcibiades II'', ''Hipparchus (dialogue), Hipparchus'', ''Rival Lovers, Lovers''

*5th tetralogy

**''Theages'',

Thirty-five dialogues and thirteen letters (the Epistles (Plato), ''Epistles'') have traditionally been ascribed to Plato, though modern scholarship doubts the authenticity of at least some of these. Plato's writings have been published in several fashions; this has led to several conventions regarding the naming and referencing of Plato's texts.

The usual system for making unique references to sections of the text by Plato derives from a 16th-century edition of Plato's works by Henri Estienne, Henricus Stephanus known as Stephanus pagination.

One tradition regarding the arrangement of Plato's texts is according to tetralogy, tetralogies. This scheme is ascribed by Diogenes La√Ђrtius to an ancient scholar and court astrologer to Tiberius named Thrasyllus of Mendes, Thrasyllus. The list includes works of doubtful authenticity (written in italic), and includes the Letters.

*1st tetralogy

**Euthyphro, Apology (Plato), Apology, Crito, Phaedo

*2nd tetralogy

**Cratylus (dialogue), Cratylus, Theaetetus (dialogue), Theatetus, Sophist (dialogue), Sophist, Statesman (dialogue), Statesman

*3nd tetralogy

**Parmenides (dialogue), Parmenides, Philebus, Symposium (Plato), Symposium, Phaedrus (dialogue), Phaedrus

*4th tetralogy

**First Alcibiades, Alcibiades I, ''Second Alcibiades, Alcibiades II'', ''Hipparchus (dialogue), Hipparchus'', ''Rival Lovers, Lovers''

*5th tetralogy

**''Theages'', Chronology

No one knows the exact order Plato's dialogues were written in, nor the extent to which some might have been later revised and rewritten. The works are usually grouped into ''Early'' (sometimes by some into ''Transitional''), ''Middle'', and ''Late'' period. This choice to group chronologically is thought worthy of criticism by some (Cooper ''et al''), given that it is recognized that there is no absolute agreement as to the true chronology, since the facts of the temporal order of writing are not confidently ascertained. Chronology was not a consideration in ancient times, in that groupings of this nature are ''virtually absent'' (Tarrant) in the extant writings of ancient Platonists. Whereas those classified as "early dialogues" often conclude in aporia, the so-called "middle dialogues" provide more clearly stated positive teachings that are often ascribed to Plato such as the theory of Forms. The remaining dialogues are classified as "late" and are generally agreed to be difficult and challenging pieces of philosophy. This grouping is the only one proven by stylometric analysis. Among those who classify the dialogues into periods of composition, Socrates figures in all of the "early dialogues" and they are considered the most faithful representations of the historical Socrates. The following represents one relatively common division. It should, however, be kept in mind that many of the positions in the ordering are still highly disputed, and also that the very notion that Plato's dialogues can or should be "ordered" is by no means universally accepted. Increasingly in the most recent Plato scholarship, writers are sceptical of the notion that the order of Plato's writings can be established with any precision, though Plato's works are still often characterized as falling at least roughly into three groups. Early: ''Apology (Plato), Apology'', ''Writings of doubted authenticity

Jowett mentions in his Appendix to Menexenus, that works which bore the character of a writer were attributed to that writer even when the actual author was unknown. For below: (*) if there is no consensus among scholars as to whether Plato is the author, and (вА°) if most scholars agree that Plato is ''not'' the author of the work. ''First Alcibiades, Alcibiades I'' (*), ''Second Alcibiades, Alcibiades II'' (вА°), ''Clitophon (dialogue), Clitophon'' (*), ''Epinomis'' (вА°), ''Epistles (Plato), Letters'' (*), ''Hipparchus (dialogue), Hipparchus'' (вА°), ''Menexenus (dialogue), Menexenus'' (*), ''Minos (dialogue), Minos'' (вА°), ''Rival Lovers, Lovers'' (вА°), ''Theages'' (вА°)Spurious writings

The following works were transmitted under Plato's name, most of them already considered spurious in antiquity, and so were not included by Thrasyllus in his tetralogical arrangement. These works are labelled as ''Notheuomenoi'' ("spurious") or ''Apocrypha''. ''Axiochus (dialogue), Axiochus'', ''Definitions (Plato), Definitions'', ''Demodocus (dialogue), Demodocus'', ''Epigrams (Plato), Epigrams'', ''Eryxias (dialogue), Eryxias'', ''Halcyon (dialogue), Halcyon'', ''On Justice'', ''On Virtue'', ''Sisyphus (dialogue), Sisyphus''.Textual sources and history

Some 250 known manuscripts of Plato survive. The texts of Plato as received today apparently represent the complete written philosophical work of Plato and are generally good by the standards of textual criticism. No modern edition of Plato in the original Greek represents a single source, but rather it is reconstructed from multiple sources which are compared with each other. These sources are medieval manuscripts written on vellum (mainly from 9th to 13th century AD Byzantium), papyri (mainly from late antiquity in Egypt), and from the independent ''testimonia'' of other authors who quote various segments of the works (which come from a variety of sources). The text as presented is usually not much different from what appears in the Byzantine manuscripts, and papyri and testimonia just confirm the manuscript tradition. In some editions, however, the readings in the papyri or testimonia are favoured in some places by the editing critic of the text. Reviewing editions of papyri for the ''Republic'' in 1987, Slings suggests that the use of papyri is hampered due to some poor editing practices.

In the first century AD, Thrasyllus of Mendes had compiled and published the works of Plato in the original Greek, both genuine and spurious. While it has not survived to the present day, all the extant medieval Greek manuscripts are based on his edition.

The oldest surviving complete manuscript for many of the dialogues is the Clarke Plato (Codex Oxoniensis Clarkianus 39, or Codex Boleianus MS E.D. Clarke 39), which was written in Constantinople in 895 and acquired by Oxford University in 1809. The Clarke is given the sigla, siglum ''B'' in modern editions. ''B'' contains the first six tetralogies and is described internally as being written by "John the Calligrapher" on behalf of Arethas of Caesarea. It appears to have undergone corrections by Arethas himself. For the last two tetralogies and the apocrypha, the oldest surviving complete manuscript is Codex Parisinus graecus 1807, designated ''A'', which was written nearly contemporaneously to ''B'', circa 900 AD. ''A'' must be a copy of the edition edited by the patriarch, Photios I of Constantinople, Photios, teacher of Arethas.''A'' probably had an initial volume containing the first 7 tetralogies which is now lost, but of which a copy was made, Codex Venetus append. class. 4, 1, which has the siglum ''T''. The oldest manuscript for the seventh tetralogy is Codex Vindobonensis 54. suppl. phil. Gr. 7, with siglum ''W'', with a supposed date in the twelfth century. In total there are fifty-one such Byzantine manuscripts known, while others may yet be found.

To help establish the text, the older evidence of papyri and the independent evidence of the testimony of commentators and other authors (i.e., those who quote and refer to an old text of Plato which is no longer extant) are also used. Many papyri which contain fragments of Plato's texts are among the Oxyrhynchus Papyri. The 2003 Oxford Classical Texts edition by Slings even cites the Coptic translation of a fragment of the ''Republic'' in the Nag Hammadi library as evidence. Important authors for testimony include Olympiodorus the Younger, Plutarch, Proclus, Iamblichus, Eusebius, and Stobaeus.

During the early Renaissance, the Greek language and, along with it, Plato's texts were reintroduced to Western Europe by Byzantine scholars. In September or October 1484 Filippo Valori and Francesco Berlinghieri printed 1025 copies of Marsilio Ficino, Ficino's translation, using the printing press at the Dominican convent S.Jacopo di Ripoli. Cosimo had been influenced toward studying Plato by the many Byzantine Platonists in Florence during his day, including George Gemistus Plethon.

The 1578 edition of Plato's complete works published by Henricus Stephanus (Henri Estienne) in Geneva also included parallel Latin translation and running commentary by Joannes Serranus (Jean de Serres). It was this edition which established standard Stephanus pagination, still in use today.

Some 250 known manuscripts of Plato survive. The texts of Plato as received today apparently represent the complete written philosophical work of Plato and are generally good by the standards of textual criticism. No modern edition of Plato in the original Greek represents a single source, but rather it is reconstructed from multiple sources which are compared with each other. These sources are medieval manuscripts written on vellum (mainly from 9th to 13th century AD Byzantium), papyri (mainly from late antiquity in Egypt), and from the independent ''testimonia'' of other authors who quote various segments of the works (which come from a variety of sources). The text as presented is usually not much different from what appears in the Byzantine manuscripts, and papyri and testimonia just confirm the manuscript tradition. In some editions, however, the readings in the papyri or testimonia are favoured in some places by the editing critic of the text. Reviewing editions of papyri for the ''Republic'' in 1987, Slings suggests that the use of papyri is hampered due to some poor editing practices.

In the first century AD, Thrasyllus of Mendes had compiled and published the works of Plato in the original Greek, both genuine and spurious. While it has not survived to the present day, all the extant medieval Greek manuscripts are based on his edition.

The oldest surviving complete manuscript for many of the dialogues is the Clarke Plato (Codex Oxoniensis Clarkianus 39, or Codex Boleianus MS E.D. Clarke 39), which was written in Constantinople in 895 and acquired by Oxford University in 1809. The Clarke is given the sigla, siglum ''B'' in modern editions. ''B'' contains the first six tetralogies and is described internally as being written by "John the Calligrapher" on behalf of Arethas of Caesarea. It appears to have undergone corrections by Arethas himself. For the last two tetralogies and the apocrypha, the oldest surviving complete manuscript is Codex Parisinus graecus 1807, designated ''A'', which was written nearly contemporaneously to ''B'', circa 900 AD. ''A'' must be a copy of the edition edited by the patriarch, Photios I of Constantinople, Photios, teacher of Arethas.''A'' probably had an initial volume containing the first 7 tetralogies which is now lost, but of which a copy was made, Codex Venetus append. class. 4, 1, which has the siglum ''T''. The oldest manuscript for the seventh tetralogy is Codex Vindobonensis 54. suppl. phil. Gr. 7, with siglum ''W'', with a supposed date in the twelfth century. In total there are fifty-one such Byzantine manuscripts known, while others may yet be found.

To help establish the text, the older evidence of papyri and the independent evidence of the testimony of commentators and other authors (i.e., those who quote and refer to an old text of Plato which is no longer extant) are also used. Many papyri which contain fragments of Plato's texts are among the Oxyrhynchus Papyri. The 2003 Oxford Classical Texts edition by Slings even cites the Coptic translation of a fragment of the ''Republic'' in the Nag Hammadi library as evidence. Important authors for testimony include Olympiodorus the Younger, Plutarch, Proclus, Iamblichus, Eusebius, and Stobaeus.

During the early Renaissance, the Greek language and, along with it, Plato's texts were reintroduced to Western Europe by Byzantine scholars. In September or October 1484 Filippo Valori and Francesco Berlinghieri printed 1025 copies of Marsilio Ficino, Ficino's translation, using the printing press at the Dominican convent S.Jacopo di Ripoli. Cosimo had been influenced toward studying Plato by the many Byzantine Platonists in Florence during his day, including George Gemistus Plethon.

The 1578 edition of Plato's complete works published by Henricus Stephanus (Henri Estienne) in Geneva also included parallel Latin translation and running commentary by Joannes Serranus (Jean de Serres). It was this edition which established standard Stephanus pagination, still in use today.

Modern editions

The Oxford Classical Texts offers the current standard complete Greek text of Plato's complete works. In five volumes edited by John Burnet (classicist), John Burnet, its first edition was published 1900вАУ1907, and it is still available from the publisher, having last been printed in 1993. The second edition is still in progress with only the first volume, printed in 1995, and the ''Republic'', printed in 2003, available. The ''Cambridge Greek and Latin Texts'' and ''Cambridge Classical Texts and Commentaries'' series includes Greek editions of the ''Protagoras'', ''Symposium'', ''Phaedrus'', ''Alcibiades'', and ''Clitophon'', with English philological, literary, and, to an extent, philosophical commentary. One distinguished edition of the Greek text is E. R. Dodds' of the ''Gorgias'', which includes extensive English commentary. The modern standard complete English edition is the 1997 Hackett Publishing Company, Hackett ''Plato, Complete Works'', edited by John M. Cooper. For many of these translations Hackett offers separate volumes which include more by way of commentary, notes, and introductory material. There is also the ''Clarendon Plato Series'' by Oxford University Press which offers English translations and thorough philosophical commentary by leading scholars on a few of Plato's works, including John McDowell's version of the ''Theaetetus''. Cornell University Press has also begun the ''Agora'' series of English translations of classical and medieval philosophical texts, including a few of Plato's.Criticism

The most famous criticism of the Theory of Forms is the Third Man Argument by Aristotle in the ''Metaphysics''. Plato had actually already considered this objection with the idea of "large" rather than "man," in the dialogue ''Parmenides (dialogue), Parmenides'', using the elderly Elean philosophersLegacy

In the arts

Plato's Academy mosaic was created in the villa of T. Siminius Stephanus in Pompeii, around 100 BC to 100 CE. ''The School of Athens'' fresco by Raphael features Plato also as a central figure. The Nuremberg Chronicle depicts Plato and others as anachronistic schoolmen.

Plato's Academy mosaic was created in the villa of T. Siminius Stephanus in Pompeii, around 100 BC to 100 CE. ''The School of Athens'' fresco by Raphael features Plato also as a central figure. The Nuremberg Chronicle depicts Plato and others as anachronistic schoolmen.

In philosophy

Plato's thought is often compared with that of his most famous student, The political philosopher and professor Leo Strauss is considered by some as the prime thinker involved in the recovery of Platonic thought in its more political, and less metaphysical, form. Strauss' political approach was in part inspired by the appropriation of Plato and Aristotle by medieval Jewish philosophy, Jewish and Islamic philosophy, Islamic Political philosophy, political philosophers, especially Maimonides and