Pierre Cot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

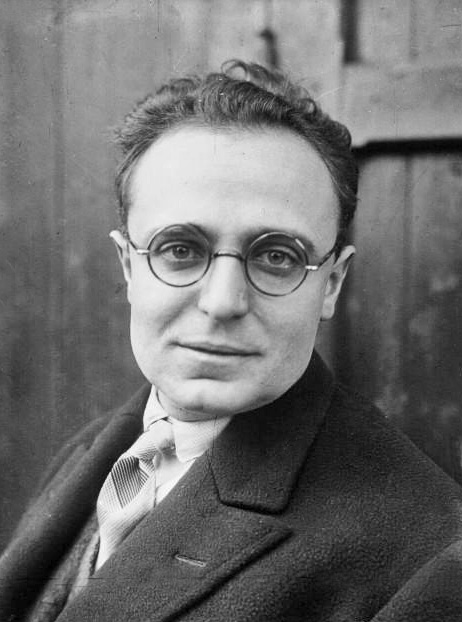

Pierre Jules Cot (20 November 1895, in

Pierre Jules Cot (20 November 1895, in

French biographical website on Pierre Cot

(with photo). This website is the main source for this article. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cot, Pierre 1895 births 1977 deaths Politicians from Grenoble Democratic Republican Alliance politicians Republican-Socialist Party politicians Radical Party (France) politicians Union progressiste politicians French Ministers of Commerce Government ministers of France Members of the 14th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 15th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 16th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the Constituent Assembly of France (1945) Members of the Constituent Assembly of France (1946) Deputies of the 1st National Assembly of the French Fourth Republic Deputies of the 2nd National Assembly of the French Fourth Republic Deputies of the 3rd National Assembly of the French Fourth Republic Deputies of the 3rd National Assembly of the French Fifth Republic Stalin Peace Prize recipients

Pierre Jules Cot (20 November 1895, in

Pierre Jules Cot (20 November 1895, in Grenoble

lat, Gratianopolis

, commune status = Prefecture and commune

, image = Panorama grenoble.png

, image size =

, caption = From upper left: Panorama of the city, Grenoble’s cable cars, place Saint- ...

– 21 August 1977, Paris), was a French politician and leading figure in the Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

government of the 1930s.

Born in Grenoble

lat, Gratianopolis

, commune status = Prefecture and commune

, image = Panorama grenoble.png

, image size =

, caption = From upper left: Panorama of the city, Grenoble’s cable cars, place Saint- ...

into a conservative Catholic family, he entered politics as an admirer of the World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

conservative leader Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (, ; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France.

Trained in law, Poincaré was elected deputy in 1 ...

, but moved steadily to the left over the course of his career. Through the decrypting of 1943 Soviet intelligence cables through the Venona Project

The Venona project was a United States counterintelligence program initiated during World War II by the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service (later absorbed by the National Security Agency), which ran from February 1, 1943, until Octob ...

it was established that Cot was an agent of the Soviet Union with the code name of "Dedal". However, other sources suggest that Cot was a communist fellow-traveller rather than an agent. The British Secret Intelligence Service describes him as "a highly controversial figure, vilified at the time by the French Right, and since accused of having been a Soviet agent".

Biography

In the 1920s Cot was a supporter ofAristide Briand

Aristide Pierre Henri Briand (; 28 March 18627 March 1932) was a French statesman who served eleven terms as Prime Minister of France during the French Third Republic. He is mainly remembered for his focus on international issues and reconciliat ...

, an independent socialist. In 1928 he was elected to the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repre ...

as a Radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

Deputy for Savoy

Savoy (; frp, Savouè ; french: Savoie ) is a cultural-historical region in the Western Alps.

Situated on the cultural boundary between Occitania and Piedmont, the area extends from Lake Geneva in the north to the Dauphiné in the south.

Savo ...

. In December 1932 he was appointed Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs in the centre-left government of Joseph Paul-Boncour

Augustin Alfred Joseph Paul-Boncour (; 4 August 1873 – 28 March 1972) was a French politician and diplomat of the Third Republic. He was a member of the Republican-Socialist Party (PRS) and served as Prime Minister of France from December 193 ...

.

In January 1933, he became Minister for Air in the Radical government of Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier (; 18 June 1884 – 10 October 1970) was a French Radical-Socialist (centre-left) politician, and the Prime Minister of France who signed the Munich Agreement before the outbreak of World War II.

Daladier was born in Carpe ...

. He oversaw the establishment of Air France

Air France (; formally ''Société Air France, S.A.''), stylised as AIRFRANCE, is the flag carrier of France headquartered in Tremblay-en-France. It is a subsidiary of the Air France–KLM Group and a founding member of the SkyTeam global air ...

, and advocated a major expansion of the French Air Force

The French Air and Space Force (AAE) (french: Armée de l'air et de l'espace, ) is the air and space force of the French Armed Forces. It was the first military aviation force in history, formed in 1909 as the , a service arm of the French Army; ...

. He was conscious of the real aim of the Nazi policy of creating sailgliding clubs through the Hitlerjugend

The Hitler Youth (german: Hitlerjugend , often abbreviated as HJ, ) was the youth organisation of the Nazi Party in Germany. Its origins date back to 1922 and it received the name ("Hitler Youth, League of German Worker Youth") in July 1926 ...

and supported the expansion of working class aero-clubs movement called Aviation Populaire as a countermeasure, but left office in February 1934 when the Stavisky Affair forced Daladier from power. He was again Minister for Air in three brief governments led by Camille Chautemps

Camille Chautemps (1 February 1885 – 1 July 1963) was a French Radical politician of the Third Republic, three times President of the Council of Ministers (Prime Minister).

He was the father-in-law of U.S. politician and statesman Howard J. ...

.

In 1936, Cot, by this time a socialist, became a leading support of the Popular Front, an alliance of the Radicals and the Socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

led by Léon Blum

André Léon Blum (; 9 April 1872 – 30 March 1950) was a French socialist politician and three-time Prime Minister.

As a Jew, he was heavily influenced by the Dreyfus affair of the late 19th century. He was a disciple of French Socialist le ...

, with the support of the French Communist Party

The French Communist Party (french: Parti communiste français, ''PCF'' ; ) is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism. The PCF is a member of the Party of the European Left, and its MEPs sit in the European Unit ...

. An antiwar activist, though not a pacifist, he was president of the International Peace Conference from 1936 to 1940. He received the Stalin Peace Prize

The International Lenin Peace Prize (russian: международная Ленинская премия мира, ''mezhdunarodnaya Leninskaya premiya mira)'' was a Soviet Union award named in honor of Vladimir Lenin. It was awarded by a pane ...

in 1953.

When Blum became Prime Minister in June 1936, Cot returned to the Air Ministry. He oversaw the nationalisation of the aeronautical industry and the launch of a re-armament program to meet the challenge of the fast-growing German Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

.

When the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

broke out, Blum's government reluctantly supported the policy of non-intervention, but Cot became a leading organiser of clandestine aid to the Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 A ...

. He organized a fictitious sale to Hejaz, Finland and Brazil of war planes, that made a flight scale in Spain.

The head of his ministerial office, Jean Moulin

Jean Pierre Moulin (; 20 June 1899 – 8 July 1943) was a French civil servant and French Resistance, resistant who served as the first President of the National Council of the Resistance during World War II from 27 May 1943 until his death less ...

(later a leader of the French Resistance

The French Resistance (french: La Résistance) was a collection of organisations that fought the German occupation of France during World War II, Nazi occupation of France and the Collaborationism, collaborationist Vichy France, Vichy régim ...

), made several trips to Spain. This brought Cot into close collaboration with the communists, with whom he had increasingly sympathised since a visit to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

in 1933. His activities were one of the factors leading to the withdrawal of the right-wing of the Radical Party from the government and Blum's resignation in June 1937. In Blum's second government in March and April 1938, Cot was Minister for Commerce.

When Daladier returned to office and signed the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

with Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

, Cot broke finally with the Radical Party.

In May 1940, Prime Minister Paul Reynaud

Paul Reynaud (; 15 October 1878 – 21 September 1966) was a French politician and lawyer prominent in the interwar period, noted for his stances on economic liberalism and militant opposition to Germany.

Reynaud opposed the Munich Agreement of ...

sent Cot on a mission to buy arms, particularly aircraft, from the Soviet Union, despite the fact that the Hitler-Stalin Pact of August 1939 had in effect made the Soviet Union a German ally. The fall of France the following month rendered his mission pointless. He flew to London and offered his services to Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

's Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

movement, but de Gaulle considered him to be too pro-communist and offered him no position. Cot then went to the United States, where he spent the war years teaching at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

.

During this period in the United States operating as a Soviet spy his controller was Vasiliy Zarubin, the chief NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

"Rezident" for the United States who operated under the name of Vasiily Zubilin."The Venona Secrets, Exposing Soviet Espionage and America's Traitors" Herbert Romerstein, Eric Breindel pg. 56

Cot was an influential figure among French political exiles, and in 1943 de Gaulle appointed him a member of the provisional French advisory assembly based in Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

. De Gaulle also sent him to Moscow to negotiate Soviet recognition of the Free French government in exile.

In 1945, Cot was again elected as Deputy for Savoy, styling himself a republican although everyone knew he remained close to the communists. In 1951, he shifted to the Rhône

The Rhône ( , ; wae, Rotten ; frp, Rôno ; oc, Ròse ) is a major river in France and Switzerland, rising in the Alps and flowing west and south through Lake Geneva and southeastern France before discharging into the Mediterranean Sea. At Ar ...

, but when de Gaulle came to power in 1958 he lost his seat. In 1967 he made a final return to politics when he was elected as an independent Deputy for Paris, with the backing of the Communist Party. He was again defeated in the right-wing landslide election of 1968. He died in Paris in 1977.

Cot's son, Jean-Pierre Cot

Jean-Pierre Cot (born 23 October 1937 in Geneva, Switzerland) is a French jurist who has served as a judge at the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea.

Biography

He is the son of Pierre Cot, also a politician and minister.

After stu ...

, was a minister in the Socialist government of Pierre Mauroy

Pierre Mauroy (; 5 July 1928 – 7 June 2013) was a French Socialist politician who was Prime Minister of France from 1981 to 1984 under President François Mitterrand. Mauroy also served as Mayor of Lille from 1973 to 2001. At the time of his de ...

in 1981–82 and was a member of the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and informally as the Council of Ministers), it adopts ...

in 1978–1979 and 1984–1999. Since 2002 he has been a member of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea

International is an adjective (also used as a noun) meaning "between nations".

International may also refer to:

Music Albums

* ''International'' (Kevin Michael album), 2011

* ''International'' (New Order album), 2002

* ''International'' (The T ...

.

References

External links

French biographical website on Pierre Cot

(with photo). This website is the main source for this article. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cot, Pierre 1895 births 1977 deaths Politicians from Grenoble Democratic Republican Alliance politicians Republican-Socialist Party politicians Radical Party (France) politicians Union progressiste politicians French Ministers of Commerce Government ministers of France Members of the 14th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 15th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the 16th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic Members of the Constituent Assembly of France (1945) Members of the Constituent Assembly of France (1946) Deputies of the 1st National Assembly of the French Fourth Republic Deputies of the 2nd National Assembly of the French Fourth Republic Deputies of the 3rd National Assembly of the French Fourth Republic Deputies of the 3rd National Assembly of the French Fifth Republic Stalin Peace Prize recipients