pieds-noirs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Pieds-Noirs'' (; ; ''Pied-Noir''), are the people of French and other

There are competing theories about the origin of the term ''"pied-noir"''. According to the ''

There are competing theories about the origin of the term ''"pied-noir"''. According to the ''

European settlement of Algeria began during the 1830s, after France had commenced the process of conquest with the military seizure of the city of Algiers in 1830. The invasion was instigated when the

European settlement of Algeria began during the 1830s, after France had commenced the process of conquest with the military seizure of the city of Algiers in 1830. The invasion was instigated when the

From roughly the last half of the 19th century until independence, the ''Pieds-Noirs'' accounted for approximately 10% of the total Algerian population. Although they constituted a numerical minority, they were undoubtedly the prime political and economic force of the region.

In 1959, the ''Pieds-Noirs'' numbered 1,025,000, and accounted for 10.4% of the total population of Algeria, a percentage gradually diminishing since the peak of 15.2% in 1926. However, some areas of Algeria had high concentrations of ''Pieds-Noirs'', such as the regions of Bône (now

From roughly the last half of the 19th century until independence, the ''Pieds-Noirs'' accounted for approximately 10% of the total Algerian population. Although they constituted a numerical minority, they were undoubtedly the prime political and economic force of the region.

In 1959, the ''Pieds-Noirs'' numbered 1,025,000, and accounted for 10.4% of the total population of Algeria, a percentage gradually diminishing since the peak of 15.2% in 1926. However, some areas of Algeria had high concentrations of ''Pieds-Noirs'', such as the regions of Bône (now

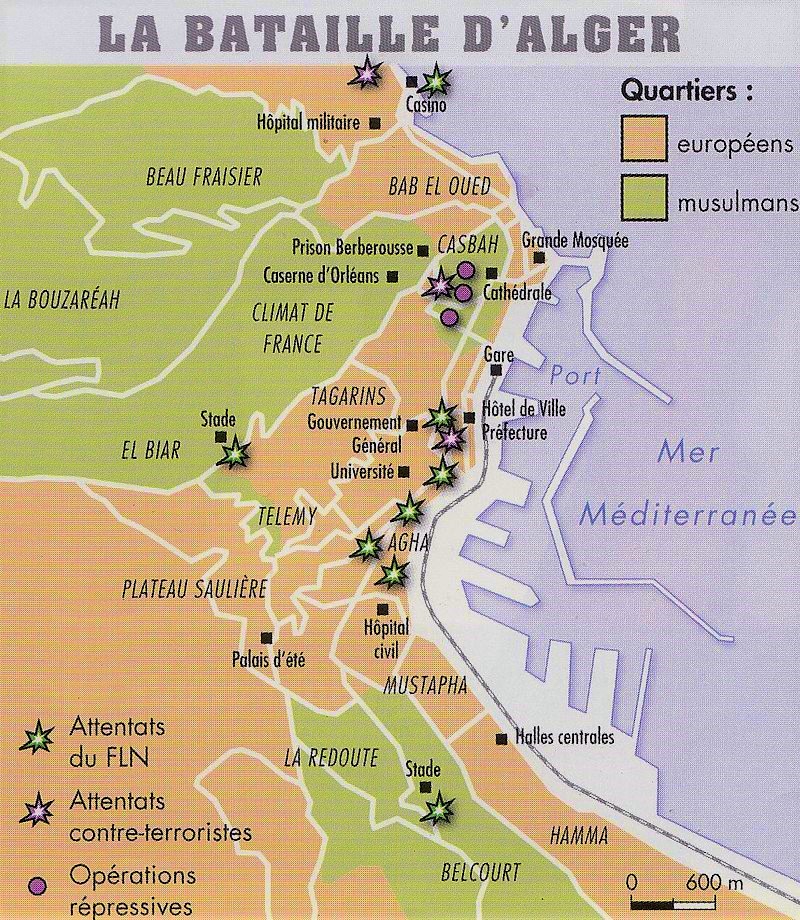

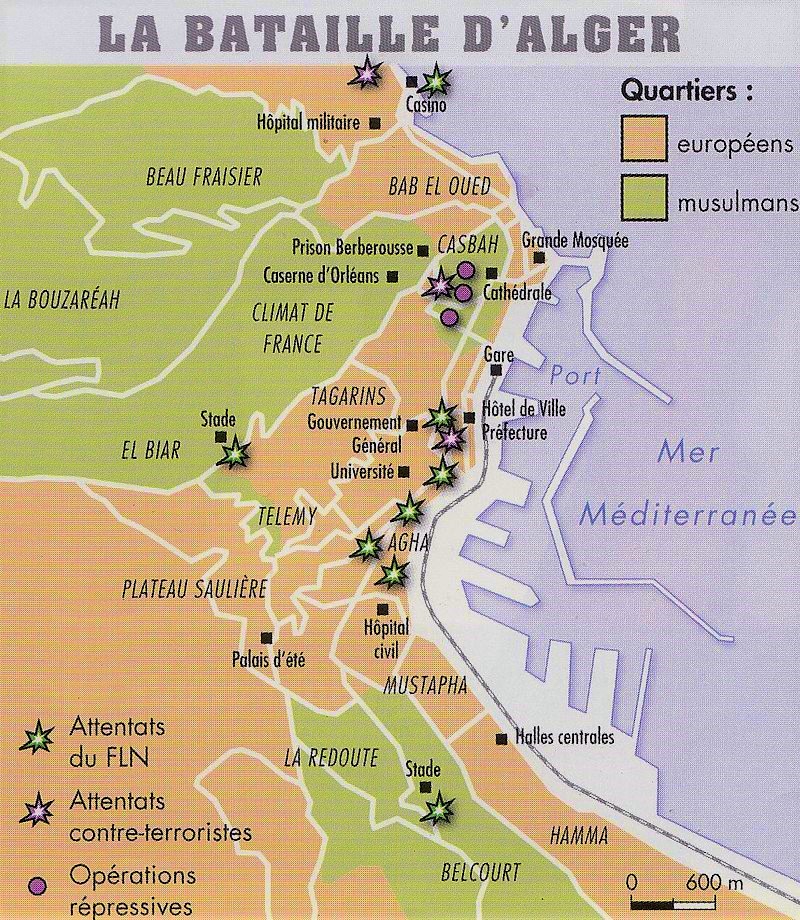

From the first armed operations of November 1954, ''Pied-Noir'' civilians had always been targets for the FLN, either by assassination; bombing bars and cinemas; mass massacres; torture; and rapes in farms.

At the onset of the war, the ''Pieds-Noirs'' believed the French military would be able to overcome opposition. In May 1958 a demonstration for French Algeria, led by ''Pieds-Noirs'' but including many Muslims, occupied an Algerian government building. Plots to overthrow the Fourth Republic, some including metropolitan French politicians and generals, had been swirling in Algeria for some time. General Jacques Massu controlled the riot by forming a 'Committee of Public Safety' demanding that his acquaintance

From the first armed operations of November 1954, ''Pied-Noir'' civilians had always been targets for the FLN, either by assassination; bombing bars and cinemas; mass massacres; torture; and rapes in farms.

At the onset of the war, the ''Pieds-Noirs'' believed the French military would be able to overcome opposition. In May 1958 a demonstration for French Algeria, led by ''Pieds-Noirs'' but including many Muslims, occupied an Algerian government building. Plots to overthrow the Fourth Republic, some including metropolitan French politicians and generals, had been swirling in Algeria for some time. General Jacques Massu controlled the riot by forming a 'Committee of Public Safety' demanding that his acquaintance

The exodus began once it became clear that Algeria would become independent. In Algiers, it was reported that by May 1961 the ''Pieds-Noirs' '' morale had sunk because of violence and allegations that the entire community of French nationals had been responsible for "terrorism, torture, colonial racism, and ongoing violence in general" and because the group felt "rejected by the nation as ''Pieds-Noirs'' ". These factors, the Oran Massacre, and the referendum for independence caused the ''Pied-Noir'' exodus to begin in earnest.

The number of ''Pieds-Noirs'' who fled Algeria totalled more than 800,000 between 1962 and 1964. Many ''Pieds-Noirs'' left only with what they could carry in a suitcase. Adding to the confusion, the de Gaulle government ordered the

The exodus began once it became clear that Algeria would become independent. In Algiers, it was reported that by May 1961 the ''Pieds-Noirs' '' morale had sunk because of violence and allegations that the entire community of French nationals had been responsible for "terrorism, torture, colonial racism, and ongoing violence in general" and because the group felt "rejected by the nation as ''Pieds-Noirs'' ". These factors, the Oran Massacre, and the referendum for independence caused the ''Pied-Noir'' exodus to begin in earnest.

The number of ''Pieds-Noirs'' who fled Algeria totalled more than 800,000 between 1962 and 1964. Many ''Pieds-Noirs'' left only with what they could carry in a suitcase. Adding to the confusion, the de Gaulle government ordered the

File:Drapeau des Français d'Algérie.svg, Flag proposed by Jean-Paul Gavino

File:Flag of France (Pieds-noirs).svg, Tricolore flag with two black feet

File:Drapeau USDIFRA.svg, Flag of the USDIFRA using pied-noir symbolism

File:État Pied Noir.svg, État Pied-Noir flag to the claim

listen to the Chant des Africains

The "Song of the Africans" was banned from use as official military music in 1962 at the end of the Algerian War until August 1969, when the French Minister of Veterans Affairs (''Ministre des Anciens Combattants'') at the time, Henri Duvillard, lifted the prohibition.

European descent

White is a racialized classification of people and a skin color specifier, generally used for people of European origin, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, and point of view.

Description of populations as " ...

who were born in Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

during the period of French rule from 1830 to 1962; the vast majority of whom departed for mainland France

Metropolitan France (french: France métropolitaine or ''la Métropole''), also known as European France (french: Territoire européen de la France) is the area of France which is geographically in Europe. This collective name for the European ...

as soon as Algeria gained independence or in the months following.

From the French invasion on 18 June 1830 until its independence, Algeria was administratively part of France; its European population were simply called Algerians or ''colons'' (colonists), whereas the Muslim people of Algeria were called Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

, Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraha ...

or Indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

. The term ''"pied-noir"'' began to be commonly used shortly before the end of the Algerian War

The Algerian War, also known as the Algerian Revolution or the Algerian War of Independence,( ar, الثورة الجزائرية '; '' ber, Tagrawla Tadzayrit''; french: Guerre d'Algérie or ') and sometimes in Algeria as the War of 1 November ...

in 1962. As of the last census in French-ruled Algeria, taken on 1 June 1960, there were 1,050,000 non-Muslim civilians (mostly Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, but including 130,000 Algerian Jews

The History of the Jews in Algeria refers to the history of the Jewish community of Algeria, which dates to the 1st century CE. In the 15th century, many Spanish Jews fled to the Maghreb, including today's Algeria, following expulsion from Spai ...

) in Algeria, 10 per cent of the population.

During the Algerian War the ''Pieds-Noirs'' overwhelmingly supported colonial French rule in Algeria and were opposed to Algerian nationalist groups such as the '' Front de libération nationale'' (English: National Liberation Front) (FLN) and ''Mouvement national algérien

The Algerian National Movement (french: Mouvement national algérien, or MNA, Tamazight: ''Amussu Aɣelnaw Adzayri'', ar, الحركة الوطنية الجزائرية) was an organization founded to counteract the efforts of the Front de Libér ...

'' (English: Algerian National Movement) (MNA). The roots of the conflict lay in political and economic inequalities perceived as an "alienation" from the French rule as well as a demand for a leading position for the Berber, Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

and Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

ic cultures and rules existing before the French conquest. The conflict contributed to the fall of the French Fourth Republic

The French Fourth Republic (french: Quatrième république française) was the Republicanism, republican government of France from 27 October 1946 to 4 October 1958, governed by the fourth republican constitution. It was in many ways a revival of ...

and the exodus of European and Jewish Algerians to France.

After Algeria became independent in 1962, about 800,000 ''Pieds-Noirs'' of French nationality were evacuated to mainland France, while about 200,000 remained in Algeria. Of the latter, there were still about 100,000 in 1965 and about 50,000 by the end of the 1960s."Pieds-noirs": ceux qui ont choisi de resterLa Dépêche du Midi

''La Dépêche'', formally ''La Dépêche du Midi'', is a regional daily newspaper published in Toulouse in Southwestern France with seventeen editions for different areas of the Midi-Pyrénées region. The main local editions are for Toulouse, ...

, March 2012

Those who moved to France suffered ostracism from the left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relative direction opposite of right

* L ...

for their perceived exploitation of native Muslims, while others blamed them for the war and thus for the political turmoil surrounding the collapse of the Fourth Republic. In popular culture, the community is often represented as feeling removed from French culture

The culture of France has been shaped by geography, by historical events, and by foreign and internal forces and groups. France, and in particular Paris, has played an important role as a center of high culture since the 17th century and from t ...

while longing for Algeria. Thus, the recent history of the ''Pieds-Noirs'' has been characterized by a sense of twofold alienation, on the one hand from the land of their birth and on the other from their adopted homeland. Though the term ''rapatriés d'Algérie'' implies that prior to Algeria they once lived in France, most ''Pieds-Noirs'' were born in Algeria.

Etymology

Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a com ...

'', it refers to "a person of European origin living in Algeria during the period of French rule, especially a French person expatriated after Algeria was granted independence in 1962." The ''Le Robert

Le Robert (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Wobè) is a town and the third-largest commune in the French overseas department of Martinique. It is located in the northeastern (Atlantic) side of the island of Martinique. It contains the Sainte Ros ...

'' dictionary states that in 1901 the word indicated a sailor working barefoot in the coal room of a ship, who would find his feet blackened by the soot and dust. Since, in the Mediterranean, this was often an Algerian native, the term was used pejoratively for Algerians until 1955 when it first began referring to "French born in Algeria" according to some sources. The ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a com ...

'' claims this usage originated from mainland French as a negative nickname.

There is also a theory that the term comes from the black boots of French soldiers compared to the barefoot Algerians. Other theories focus on new settlers dirtying their clothing by working in swampy areas, wearing black boots when on horseback, or trampling grapes to make wine.

History

French conquest and settlement

European settlement of Algeria began during the 1830s, after France had commenced the process of conquest with the military seizure of the city of Algiers in 1830. The invasion was instigated when the

European settlement of Algeria began during the 1830s, after France had commenced the process of conquest with the military seizure of the city of Algiers in 1830. The invasion was instigated when the Dey of Algiers

Dey (Arabic: داي), from the Turkish honorific title ''dayı'', literally meaning uncle, was the title given to the rulers of the Regency of Algiers (Algeria), Tripoli,Bertarelli (1929), p. 203. and Tunis under the Ottoman Empire from 1671 o ...

struck the French consul with a fly-swatter in 1827, although economic reasons are also cited. In 1830 the government of King Charles X

Charles X (born Charles Philippe, Count of Artois; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother to reigning kings Louis XVI and Loui ...

blockaded Algeria and an armada sailed to Algiers, followed by a land expedition. A troop of 34,000 soldiers landed on 18 June 1830, at Sidi Ferruch, west of Algiers. Following a three-week campaign, the Hussein Dey

Hussein Dey (real name Hüseyin bin Hüseyin; 1765 – 1838; ar, حسين داي) was the last Dey of the Deylik of Algiers.

Early life

He was born either in İzmir or Urla in the Ottoman Empire. He went to Istanbul and joined the Canoneers ...

capitulated on 5 July 1830 and was exiled.

In the 1830s the French controlled only the northern part of the country. Entering the Oran

Oran ( ar, وَهران, Wahrān) is a major coastal city located in the north-west of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria after the capital Algiers, due to its population and commercial, industrial, and cultural ...

region, they faced resistance from Emir Abd al-Kader, a leader of a Sufi

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

Brotherhood. In 1839 Abd al-Kader began a seven-year war by declaring jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with Go ...

against the French. The French signed two peace treaties with Al-Kader, but they were broken because of a miscommunication between the military and the government in Paris. In response to the breaking of the second treaty, Abd al-Kader drove the French to the coast. In reply, a force of nearly 100,000 troops marched to the Algerian countryside and forced Abd al-Kader's surrender in 1847.

In 1848 Algeria was divided into three departments ( Alger, Oran

Oran ( ar, وَهران, Wahrān) is a major coastal city located in the north-west of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria after the capital Algiers, due to its population and commercial, industrial, and cultural ...

and Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

), thus becoming part of France.

The French modeled their colonial system on their predecessors, the Ottomans, by co-opting local tribes. In 1843 the colonists began supervising through ''bureaux arabes

The Arab Bureaux (french: bureaux arabes) was a special section of colonial France's military in Algeria that was created in 1833 and effectively authorized by a ministerial order on 1 February 1844. It was staffed by French Orientalists, ethnogra ...

'' operated by military officials with authority over particular domains. This system lasted until the 1880s and the rise of the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (french: Troisième République, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940 ...

, when colonisation intensified. Large-scale regrouping of lands began when land-speculation companies took advantage of government policy that allowed massive sale of native property. By the 20th century Europeans held 1,700,000 hectares; by 1940, 2,700,000 hectares, about 35 to 40 percent; and by 1962 it was 2,726,700 hectares representing 27 percent of the arable land of Algeria.Les réformes agraires en Algérie - Lazhar Baci - Institut National Agronomique, Département d'Economie Rurale, Alger (Algérie) Settlers came from all over the western Mediterranean region, particularly Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

.

Relationship to mainland France and Muslim Algeria

The ''Pied-Noir'' relationship with France and Algeria was marked by alienation. The settlers considered themselves French, but many of the ''Pieds-Noirs'' had a tenuous connection to mainland France, which 28 percent of them had never visited. The settlers encompassed a range ofsocioeconomic

Socioeconomics (also known as social economics) is the social science that studies how economic activity affects and is shaped by social processes. In general it analyzes how modern societies progress, stagnate, or regress because of their l ...

''strata'', ranging from peasants to large landowners, the latter of whom were referred to as ''grands colons''.

In Algeria, the Muslims were not considered French and did not share the same political or economic benefits. For example, the indigenous population did not own most of the settlements, farms, or businesses, although they numbered nearly nine million (versus roughly one million ''Pieds-Noirs'') at independence. Politically, the Muslim Algerians had no representation in the French National Assembly

The National Assembly (french: link=no, italics=set, Assemblée nationale; ) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are known a ...

until 1945 and wielded limited influence in local governance. To obtain citizenship, they were required to renounce their Muslim identity. Since this would constitute apostasy

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that i ...

, only about 2,500 Muslims acquired citizenship before 1930. The settlers' politically and economically dominant position worsened relations between the two groups.

The ''Pied-Noir'' population as part of the total Algerian population

From roughly the last half of the 19th century until independence, the ''Pieds-Noirs'' accounted for approximately 10% of the total Algerian population. Although they constituted a numerical minority, they were undoubtedly the prime political and economic force of the region.

In 1959, the ''Pieds-Noirs'' numbered 1,025,000, and accounted for 10.4% of the total population of Algeria, a percentage gradually diminishing since the peak of 15.2% in 1926. However, some areas of Algeria had high concentrations of ''Pieds-Noirs'', such as the regions of Bône (now

From roughly the last half of the 19th century until independence, the ''Pieds-Noirs'' accounted for approximately 10% of the total Algerian population. Although they constituted a numerical minority, they were undoubtedly the prime political and economic force of the region.

In 1959, the ''Pieds-Noirs'' numbered 1,025,000, and accounted for 10.4% of the total population of Algeria, a percentage gradually diminishing since the peak of 15.2% in 1926. However, some areas of Algeria had high concentrations of ''Pieds-Noirs'', such as the regions of Bône (now Annaba

Annaba ( ar, عنّابة, "Place of the Jujubes"; ber, Aânavaen), formerly known as Bon, Bona and Bône, is a seaport city in the northeastern corner of Algeria, close to the border with Tunisia. Annaba is near the small Seybouse River ...

), Algiers, and above all the area from Oran

Oran ( ar, وَهران, Wahrān) is a major coastal city located in the north-west of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria after the capital Algiers, due to its population and commercial, industrial, and cultural ...

to Sidi-Bel-Abbès. Oran had been under European rule since the 16th century (1509); the population in the Oran metropolitan area was 49.3% European and Jewish in 1959.

In the Algiers metropolitan area, Europeans and Jewish people accounted for 35.7% of the population. In the metropolitan area of Bône they accounted for 40.5% of the population. The ''département'' of Oran, a rich European-developed agricultural land of 16,520 km2 (6,378 sq. miles) stretching between the cities of Oran and Sidi-Bel-Abbès, and including them, was the area of highest ''Pied-Noir'' density outside of the cities, with the ''Pieds-Noirs'' accounting for 33.6% of the population of the ''département

In the administrative divisions of France, the department (french: département, ) is one of the three levels of government under the national level ("territorial collectivity, territorial collectivities"), between the regions of France, admin ...

'' in 1959.

Sephardic Jewish community

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

were present in North Africa and Iberia for centuries, some since the time when "Phoenicians and Hebrews, engaged in maritime commerce, founded Hippo Regius (current Annaba), Tipasa

Tipasa, sometimes distinguished as Tipasa in Mauretania, was a colonia in the Roman province Mauretania Caesariensis, nowadays called Tipaza, and located in coastal central Algeria. Since 1982, it has been declared by UNESCO a World Heritage Si ...

, Caesarea (current Cherchel

Cherchell (Arabic: شرشال) is a town on Algeria's Mediterranean coast, west of Algiers. It is the seat of Cherchell District in Tipaza Province. Under the names Iol and Caesarea, it was formerly a Roman colony and the capital of the k ...

), and Icosium (current Algiers)". According to oral tradition they arrived from Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Hebrew language#Modern Hebrew, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian vocalization, Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous L ...

after the First Jewish-Roman War

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

(66–73 AD), while it is known historically that many Sephardi Jews

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefar ...

came following the Spanish ''Reconquista

The ' (Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the Nasrid ...

''. In 1870, Justice Minister Adolphe Crémieux

Isaac-Jacob Adolphe Crémieux (; 30 April 1796 – 10 February 1880) was a French lawyer and politician who served as Minister of Justice under the Second Republic (1848) and Government of National Defense (1870–1871). He served as presiden ...

wrote a proposal, '' décret Crémieux'', giving French citizenship to Algerian Jews. This advancement was resisted by part of the larger ''Pied-Noir'' community and in 1897 a wave of anti-Semitic riots occurred in Algeria. During World War II the ''décret Crémieux'' was abolished under the Vichy

Vichy (, ; ; oc, Vichèi, link=no, ) is a city in the Allier department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of central France, in the historic province of Bourbonnais.

It is a spa and resort town and in World War II was the capital of ...

regime, and Jews were barred from professional jobs between 1940 and 1943. Citizenship was restored in 1943, after the Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

took control over Algeria in the wake of Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

. Thus, the Jews of Algeria eventually came to be considered part of the ''Pied-Noir'' community, and many fled the country to France in 1962, alongside most other ''Pieds-Noirs'', after the Algerian War.

Algerian War and exodus

Algerian War

For more than a century France maintainedcolonial rule

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colony, colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose the ...

in Algerian territory. This allowed exceptions to republican law, including Sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

laws applied by Islamic customary courts to Muslim women which gave women certain rights to property and inheritance that they did not have under French law. Discontent among the Muslim Algerians grew after the World Wars, in which the Algerians sustained many casualties. Algerian nationalists began efforts aimed at furthering equality by listing complaints in the ''Manifesto of the Algerian People'', which requested equal representation under the state and access to citizenship, but no equality for all citizens to preserve Islamic precepts. The French response was to grant citizenship to 60,000 "meritorious" Muslims. During a reform effort in 1947, the French laws were changed to give the former French subjects with the legal status of "indigenes" full French legal citizenship. The French created an Algerian Assembly, a form of bicameral legislature, with limited powers, and two chambers, one for those who were French citizens before 1947, and another for all the others who had only just become French citizens; but given the equal numbers of members in each chamber this meant that one group's votes had seven times more weight than the other group's. Paramilitary groups such as the National Liberation Front (''Front de Libération nationale'', FLN) appeared, claiming an Arab-Islamic brotherhood and state. This led to the outbreak of a war for independence, the Algerian War

The Algerian War, also known as the Algerian Revolution or the Algerian War of Independence,( ar, الثورة الجزائرية '; '' ber, Tagrawla Tadzayrit''; french: Guerre d'Algérie or ') and sometimes in Algeria as the War of 1 November ...

, in 1954.

From the first armed operations of November 1954, ''Pied-Noir'' civilians had always been targets for the FLN, either by assassination; bombing bars and cinemas; mass massacres; torture; and rapes in farms.

At the onset of the war, the ''Pieds-Noirs'' believed the French military would be able to overcome opposition. In May 1958 a demonstration for French Algeria, led by ''Pieds-Noirs'' but including many Muslims, occupied an Algerian government building. Plots to overthrow the Fourth Republic, some including metropolitan French politicians and generals, had been swirling in Algeria for some time. General Jacques Massu controlled the riot by forming a 'Committee of Public Safety' demanding that his acquaintance

From the first armed operations of November 1954, ''Pied-Noir'' civilians had always been targets for the FLN, either by assassination; bombing bars and cinemas; mass massacres; torture; and rapes in farms.

At the onset of the war, the ''Pieds-Noirs'' believed the French military would be able to overcome opposition. In May 1958 a demonstration for French Algeria, led by ''Pieds-Noirs'' but including many Muslims, occupied an Algerian government building. Plots to overthrow the Fourth Republic, some including metropolitan French politicians and generals, had been swirling in Algeria for some time. General Jacques Massu controlled the riot by forming a 'Committee of Public Safety' demanding that his acquaintance Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

be named president of the French Fourth Republic

The French Fourth Republic (french: Quatrième république française) was the Republicanism, republican government of France from 27 October 1946 to 4 October 1958, governed by the fourth republican constitution. It was in many ways a revival of ...

, to prevent the "abandonment of Algeria". This eventually led to the fall of the Republic. In response, the French Parliament voted 329 to 224 to place de Gaulle in power. Once de Gaulle assumed leadership, he attempted peace by visiting Algeria within three days of his appointment, proclaiming "French Algeria!"; but in September 1959 he planned a referendum for Algerian self-determination that passed overwhelmingly. Many French political and military leaders in Algeria viewed this as a betrayal and formed the ''Organisation armée secrète

The ''Organisation Armée Secrète'' (OAS, "Secret Armed Organisation") was a far-right French dissident paramilitary organisation during the Algerian War. The OAS carried out terrorist attacks, including bombings and assassinations, in an atte ...

'' (OAS) that had much support among ''Pieds-Noirs''. This paramilitary group began attacking officials representing de Gaulle's authority, Muslims, and de Gaulle himself. The OAS was also accused of murders and bombings which nullified any remaining reconciliation opportunities between the communities, while ''Pieds-Noirs'' themselves never believed such reconciliation possible as their community was targeted from the start.

The opposition culminated in the Algiers putsch of 1961

The Algiers putsch (french: Putsch d'Alger or ), also known as the Generals' putsch (''Putsch des généraux''), was a failed coup d'état intended to force French President Charles de Gaulle not to abandon French Algeria, along with the resid ...

, led by retired generals. After its failure, on 18 March 1962, de Gaulle and the FLN signed a cease-fire agreement, the Évian Accords

The Évian Accords were a set of peace treaties signed on 18 March 1962 in Évian-les-Bains, France, by France and the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic, the government-in-exile of FLN (), which sought Algeria's independence ...

, and held a referendum. In July, Algerians voted 5,975,581 to 16,534 to become independent from France.

This triggered a massacre of ''Pieds-Noirs'' in Oran by a suburban Muslim population. European people were shot, raped, lynched and brought to Petit-Lac slaughterhouse

A slaughterhouse, also called abattoir (), is a facility where animals are slaughtered to provide food. Slaughterhouses supply meat, which then becomes the responsibility of a packaging facility.

Slaughterhouses that produce meat that is no ...

where they were tortured and executed.

Exodus

The exodus began once it became clear that Algeria would become independent. In Algiers, it was reported that by May 1961 the ''Pieds-Noirs' '' morale had sunk because of violence and allegations that the entire community of French nationals had been responsible for "terrorism, torture, colonial racism, and ongoing violence in general" and because the group felt "rejected by the nation as ''Pieds-Noirs'' ". These factors, the Oran Massacre, and the referendum for independence caused the ''Pied-Noir'' exodus to begin in earnest.

The number of ''Pieds-Noirs'' who fled Algeria totalled more than 800,000 between 1962 and 1964. Many ''Pieds-Noirs'' left only with what they could carry in a suitcase. Adding to the confusion, the de Gaulle government ordered the

The exodus began once it became clear that Algeria would become independent. In Algiers, it was reported that by May 1961 the ''Pieds-Noirs' '' morale had sunk because of violence and allegations that the entire community of French nationals had been responsible for "terrorism, torture, colonial racism, and ongoing violence in general" and because the group felt "rejected by the nation as ''Pieds-Noirs'' ". These factors, the Oran Massacre, and the referendum for independence caused the ''Pied-Noir'' exodus to begin in earnest.

The number of ''Pieds-Noirs'' who fled Algeria totalled more than 800,000 between 1962 and 1964. Many ''Pieds-Noirs'' left only with what they could carry in a suitcase. Adding to the confusion, the de Gaulle government ordered the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

not to help with transportation of French citizens. By September 1962, cities such as Oran, Bône

Annaba ( ar, عنّابة, "Place of the Jujubes"; ber, Aânavaen), formerly known as Bon, Bona and Bône, is a seaport city in the northeastern corner of Algeria, close to the border with Tunisia. Annaba is near the small Seybouse River ...

, and Sidi Bel Abbès

Sidi Bel Abbès ( ar, سيدي بلعباس), also called Bel Abbès, is the capital (2005 pop. 200,000)''Sidi Bel Abbes'', lexicorient.com (Encyclopaedia of the Orient), internet article. of the Sidi Bel Abbès wilaya (2005 pop. 590,000), Alger ...

were half-empty. All administration-, police-, school-, justice-, and commercial activities stopped within three months after many ''Pieds-Noirs'' were told to choose either "''la valise ou le cercueil''" (the suitcase or the coffin). 200,000 ''Pieds-Noirs'' chose to remain, but they gradually left through the following decades; by the 1980s only a few thousand ''Pieds-Noirs'' remained in Algeria.

Along with the exodus of the ''Pieds-Noirs'', occurred the flight of the Muslim harki

''Harki'' (adjective from the Arabic ''harka'', standard Arabic ''haraka'' حركة, "war party" or "movement", i.e., a group of volunteers, especially soldiers) is the generic term for native Muslim Algerian who served as auxiliaries in the F ...

auxiliaries who had fought on the French side during the Algerian War. Of approximately 250,000 Muslim loyalists only about 90,000, including dependents, were able to escape to France; and of those who remained many thousands were killed by lynch mobs or executed as traitors by the FLN. In contrast to the treatment of the European ''Pieds-Noirs'', little effort was made by the French government to extend protection to the harkis or to arrange their organised evacuation.

Flight to mainland France

The Government of France claimed that it had not anticipated that such a massive number would leave; it believed that perhaps 300,000 might choose to depart temporarily and that a large portion would return to Algeria. The administration had set aside funds for absorption of those it called ''repatriates'' to partly reimburse them for property losses. The administration avoided acknowledging the true numbers of refugees to avoid upsetting its Algeria policies. Consequently, few plans were made for their return, and, psychologically at least, many of the ''Pieds-Noirs'' were alienated from both Algeria and France. Many ''Pieds-Noirs'' settled in continental France, while others migrated toNew Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, Spain, Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, In France, many relocated to the south, which offered a climate similar to North Africa. The influx of new citizens bolstered the local economies; however, the newcomers also competed for jobs, which caused resentment. One unintended consequence with significant and ongoing political effects was the resentment caused by the state resettlement programme for Pieds-Noirs in rural Corsica, which triggered a cultural and political nationalist movement. In some ways, the ''Pieds-Noirs'' were able to integrate well into the French community, in particular relative to their harki

''Harki'' (adjective from the Arabic ''harka'', standard Arabic ''haraka'' حركة, "war party" or "movement", i.e., a group of volunteers, especially soldiers) is the generic term for native Muslim Algerian who served as auxiliaries in the F ...

Muslim counterparts. Their resettlement was made easier by the economic boom of the 1960s. However, the ease of assimilation depended on socioeconomic class. Integration was easier for the upper classes, many of whom found the transformation less stressful than the lower classes, whose only capital had been left in Algeria when they fled. Many were surprised at often being treated as an "underclass or outsider-group" with difficulties in gaining advancement in their careers. Also, many ''Pieds-Noirs'' contended that the money allocated by the government to assist in relocation and reimbursement was insufficient regarding their loss.

Thus, the repatriated ''Pieds-Noirs'' frequently felt "disaffected" from French society. They also suffered from a sense of alienation stemming from the French government's changed position towards Algeria. Until independence, Algeria was legally a part of France; after independence many felt that they had been betrayed and were now portrayed as an "embarrassment" to their country or to blame for the war. Most ''Pied-Noirs'' felt a powerful sense of loss and a longing for their lost homeland in Algeria. The American author Claire Messud

Claire Messud (born 1966) is an American novelist and literature and creative writing professor. She is best known as the author of the novel '' The Emperor's Children'' (2006).

Early life

Born in Greenwich, Connecticut,van Gelder, Lawrence. "Foo ...

remembered seeing her ''pied-noir'' father, a lapsed Catholic crying while watching Pope John Paul II deliver a Mass on his TV. When asked why, Messud ''père'' replied: "Because when I last heard the mass in Latin, I thought I had a religion, and I thought I had a country." Messud noted that the novelist Albert Camus

Albert Camus ( , ; ; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, and journalist. He was awarded the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44, the second-youngest recipient in history. His work ...

, himself a ''pied-noir'', had often written of his love for the sea-shores and mountains of Algeria, declaring Algeria was a place that was a part of his soul, feelings she noted mirrored those of other ''pied-noirs'' for whom Algeria was the only home they had ever known.

Flags

sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

and nationhood

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by those ...

.

The Song of the Africans

The ''Pied-Noir'' community has adopted, as both an unofficial anthem and as a symbol of its identity, Captain Félix Boyer's 1943 version of " Le Chant des Africains" (lit. "The Song of the Africans"). This was a 1915 '' Infanterie de Marine'' marching song, originally titled "C'est nous les Marocains" (lit. "We are the Moroccans") and dedicated to Colonel Van Hecke, commander of a World War I cavalry unit: the '' 7e régiment de chasseurs d'Afrique'' ("7th African Light Cavalry Regiment"). Boyer's song was adopted during World War II by the Free French First Army that was drawn from units of the Army of Africa and included many ''Pieds-Noirs''. The music and words were later utilized by the ''Pieds-Noirs'' to proclaim their allegiance to France.The "Song of the Africans" was banned from use as official military music in 1962 at the end of the Algerian War until August 1969, when the French Minister of Veterans Affairs (''Ministre des Anciens Combattants'') at the time, Henri Duvillard, lifted the prohibition.

Notable ''Pieds-Noirs''

* Louis Althusser, philosopher *Jacques Attali

Jacques José Mardoché Attali (; born 1 November 1943) is a French economic and social theorist, writer, political adviser and senior civil servant, who served as a counselor to President François Mitterrand from 1981 to 1991, and was the firs ...

, economist, writer

* Paul Belmondo

Paul Alexandre Belmondo (born 23 April 1963) is a French racing driver who raced in Formula One for the March and Pacific Racing teams. He was born in Boulogne-Billancourt, Hauts-de-Seine, the son of actor Jean-Paul Belmondo and grandson of scul ...

, sculptor, father of the actor Jean-Paul Belmondo

Jean-Paul Charles Belmondo (; 9 April 19336 September 2021) was a French actor and producer. Initially associated with the New Wave of the 1960s, he was a major French film star for several decades from the 1960s onward. His best known credits ...

* Patrick Bokanowski

Patrick Bokanowski (born 23 June 1943 in Algiers, French Algeria) is a French filmmaker who makes experimental and animated films.

Career

The film '' The Angel'' (1982) is his most prominent work. It is accompanied by a soundtrack made by his wi ...

, filmmaker

* Patrick Bruel, singer

* Albert Camus

Albert Camus ( , ; ; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, and journalist. He was awarded the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44, the second-youngest recipient in history. His work ...

, Nobel Prize winning author and philosopher

* Claude Cohen-Tannoudji

Claude Cohen-Tannoudji (; born 1 April 1933) is a French physicist. He shared the 1997 Nobel Prize in Physics with Steven Chu and William Daniel Phillips for research in methods of laser cooling and trapping atoms. Currently he is still an activ ...

, Nobel laureate

* Étienne Daho

Étienne Daho (; ; born 14 January 1956) is a French singer. He has released a number of synth-driven and rock- surf influenced pop hit singles since 1981.

Career

Daho was born in Oran, French Algeria. He sings in a low, whispery voice somew ...

, singer

* Jacques Derrida

Jacques Derrida (; ; born Jackie Élie Derrida; See also . 15 July 1930 – 9 October 2004) was an Algerian-born French philosopher. He developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which he utilized in numerous texts, and which was developed t ...

, philosopher

* Annie Fratellini

Annie Violette Fratellini (14 November 1932 – 1 July 1997) was a French circus artist, singer, film actress and clown.

Biography

She was born Annie Violette Fratellini on 14 November 1932, in Algiers, French Algeria, where her parents, who w ...

, circus clown

* Tony Gatlif

Tony Gatlif (born as Michel Dahmani on 10 September 1948 in Algiers) is a French film director of Romani ethnicity who also works as a screenwriter, composer, actor, and producer.

Personal

Gatlif was born in Algeria of Pied noir ancestry. A ...

, filmmaker

* Marlène Jobert

Marlène Jobert (born 4 November 1940) is a French actress and author.

Life and career

Jobert was born in Algiers, Algeria, to a Sephardic Jewish and Pied-Noir family, the daughter of Eliane Azulay and Charles Jobert, who served in the French A ...

, actress and author

* Alphonse Juin

Alphonse Pierre Juin (16 December 1888 – 27 January 1967) was a senior French Army Army general (France), general who became Marshal of France. A graduate of the École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr, École Spéciale Militaire class of 1912, ...

, Marshal of France

Marshal of France (french: Maréchal de France, plural ') is a French military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to generals for exceptional achievements. The title has been awarded since 1185, though briefly abolished (1 ...

* Marcel Cerdan

Marcellin "Marcel" Cerdan (; 22 July 1916 – 28 October 1949) was a French professional boxer and world middleweight champion who was considered by many boxing experts and fans to be France's greatest boxer, and beyond to be one of the best to ...

, boxer

* Jean-François Larios

Jean-François Larios (born 27 August 1956) is a French former professional football midfielder. He earned seventeen international caps (five goals) for the French national team during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

A player of Saint-Étienne, ...

, footballer

* Enrico Macias, singer

* Jean Pélégri, author

* Emmanuel Roblès, author

* Yves Saint Laurent, fashion designer

See also

*Arab-Berber

Arab-Berbers ( ar, العرب والبربر ''al-ʿarab wa-l-barbar'') are a population of the Maghreb, a vast region of North Africa in the western part of the Arab world along the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. Arab-Berbers are peop ...

*Kouloughlis

Kouloughlis, also spelled Koulouglis, Cologhlis and Qulaughlis (from Turkish ''Kuloğlu'' "Children of The Empire Servants" from '' Kul'' "soldier" or "servant/slave" + '' Oğlu'' "son of"), but the translation of the word "kul" as slave is mislea ...

* European Moroccans

*European Tunisians

European Tunisians are Tunisians whose ancestry lies within the ethnic groups of Europe, notably the French. Other communities include those from Southern Europe and Northwestern Europe.

Prior to independence, there were 255,000 Europeans in Tun ...

*Italian Tunisians

Italian Tunisians (or Italians of Tunisia) are Tunisians of Italian descent. Migration and colonization, particularly during the 19th century, led to significant numbers of Italians settling in Tunisia.

Italian presence in Tunisia

The presenc ...

*Turco-Tunisians

The Turks in Tunisia, also known as Turco-Tunisians. and Tunisian Turks, ( ar, أتراك تونس; french: Turcs de Tunisie; tr, Tunus Türkleri) are ethnic Turks who constitute one of the minority groups in Tunisia..

In 1534, with about 10,0 ...

*Italian settlers in Libya

Italian settlers in Libya ( it, Italo-libici, also called Italian Libyans) typically refers to Italians and their descendants, who resided or were born in Libya during the Italian colonial period.

History

Italian heritage in Libya can be dat ...

*Etat Pied-Noir

État Pied-Noir refers to the claim made by certain Pied-Noir persons and organisations to sovereignty and nationhood.

History

The Pied-Noir are a people of European peoples, European-origin born in French colonization of Algeria, French-occupie ...

*French people

The French people (french: Français) are an ethnic group and nation primarily located in Western Europe that share a common French culture, history, and language, identified with the country of France.

The French people, especially the nati ...

*White Africans of European ancestry

White Africans of European ancestry refers to people in Africa who can trace full or partial ancestry to Europe. In 1989, there were an estimated 4.6 million white people with European ancestry on the African continent. Most are of Dutch, Portugu ...

* Retornados

*List of French possessions and colonies

From the 16th to the 17th centuries, the First French colonial empire stretched from a total area at its peak in 1680 to over , the second largest empire in the world at the time behind only the Spanish Empire. During the 19th and 20th centuri ...

Further reading

* Eldridge, Claire; Kalter, Christoph; Taylor, Becky (2022). " Migrations of Decolonization, Welfare, and the Unevenness of Citizenship in the UK, France and Portugal". ''Past & Present''.References

Sources

* Ramsay, R. (1983) ''The Corsican Time-Bomb'', Manchester University Press: Manchester. . {{good article * * * * Jewish Algerian history Ethnic groups in France Ethnic groups in Algeria Algerian War French Algeria Refugees in Africa European diaspora in Africa Refugees in France